Abstract

Objectives

Poverty reduction interventions through cash transfers and microcredit have had mixed effects on mental health. In this quasi-experimental study, we evaluate the effect of a living wage intervention on depressive symptoms of apparel factory workers in the Dominican Republic.

Setting

Two apparel factories in the Dominican Republic.

Participants

The final sample consisted of 204 hourly wage workers from the intervention (99) and comparison (105) factories.

Interventions

In 2010, an apparel factory began a living wage intervention including a 350% wage increase and significant workplace improvements. The wage increase was plausibly exogenous because workers were not aware of the living wage when applying for jobs and expected to be paid the usual minimum wage. These individuals were compared with workers at a similar local factory paying minimum wage, 15–16 months postintervention.

Primary outcome measures

Workers’ depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). Ordinary least squares and Poisson regressions were used to evaluate treatment effect of the intervention, adjusted for covariates.

Results

Intervention factory workers had fewer depressive symptoms than comparison factory workers (unadjusted mean CES-D scores: 10.6±9.3 vs 14.7±11.6, p=0.007). These results were sustained when controlling for covariates (β=−5.4, 95% CI −8.5 to −2.3, p=0.001). In adjusted analyses using the standard CES-D clinical cut-off of 16, workers at the intervention factory had a 47% reduced risk of clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms compared with workers at the comparison factory (23% vs 40%).

Conclusions

Policymakers have long grappled with how best to improve mental health among populations in low-income and middle-income countries. We find that providing a living wage and workplace improvements to improve income and well-being in a disadvantaged population is associated with reduced depressive symptoms.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to assess the impact of a living wage programme on workers’ mental health in the developing world.

This living wage programme is unique because it provides a much larger income shock (350% wage increase) than other income interventions (typically <140%) as well as significant workplace improvements.

Although not randomly assigned due to ethical and logistical constraints, workers at the intervention factory were hired with no knowledge of the living wage intervention and we statistically controlled for all covariates in adjusted analyses.

Workers earning a living wage for 15–16 months had significantly lower levels of depression symptoms compared with workers at a factory paying minimum wage.

Our results suggest that earning a living wage in a positive work environment may have a profoundly positive effect on mental health; however, data were cross sectional so causality cannot be shown.

Introduction

Depression is a common illness worldwide and an especially important global public health issue. The lifetime prevalence of depression is estimated at 12%, with even higher rates among patients with chronic medical illnesses.1 2 Depressive disorders cause significant disability and are a leading cause of the global burden of disease, increasing by 37.5% between 1990 and 2010 due to population growth and aging.3 Depression is profoundly costly to both individuals and society, and is associated with significantly increased healthcare costs.2 Women are far more likely to suffer from depression than men, and maternal depression has been shown to negatively impact child growth and development, especially in low-income and middle-income countries.4 5

Reviews of cross-sectional and longitudinal, population-based studies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America show that individuals who are poor and marginalised have a much greater risk of depression and other common mental disorders.6–8 Poverty can lead to mental illness via social causation mechanisms such as inadequate resources to manage stressors, disempowerment, stigma, malnutrition, hopelessness, helplessness, income insecurity, marginalisation, perceived deprivation and reduced access to health services.9 Mental illness can then lead to further impoverishment due to increased health costs, loss of employment and reduced productivity.9 Unfortunately, the burden of mental illness in low-income and middle-income countries has remained largely unaddressed and access to mental healthcare is often limited or non-existent.10

Recent studies of income interventions designed to combat poverty in the USA, Canada, and selected low-income and middle-income countries have found mixed effects on mental health. Rigorous randomised evaluations of welfare programmes in the USA and Canada have generally found decreased levels of depression in welfare recipients except when financial incentives were tied to employment mandates.11–14 Similarly, the introduction of a guaranteed annual income experiment in Canada was found to coincide with an 8.5% reduction in hospitalisations due to reductions in mental health and accident/injury codes.15 The smaller body of research exploring this question in low-income and middle-income countries has yielded more mixed results. Ecuador's unconditional income supplements were found to have no effect on maternal depression at 17 months,16 while Nicaragua's conditional cash transfer programme was only weakly associated with improvements in caregiver mental health after 9 months.17 However, Mexico's Oportunidades conditional cash transfer programme was associated with modest reductions in depressive symptoms,18 and caregivers in South Africa receiving child support grants were found to have significantly lower odds of common mental disorders.19 In India, women's participation in microcredit programs was associated with a lower likelihood of reporting emotional stress and poor life satisfaction,20 whereas a similar study conducted in Bangladesh did not find a relationship.21

The present study extends this body of research by evaluating the effects of a living wage and workplace improvement intervention on depressive symptoms for private sector apparel workers in the Dominican Republic. This living wage intervention is unique compared to previously studied income interventions in that it directly targets workers and provides an exogenous income increase of a much greater magnitude (approximately 3.5 times the local minimum wage). A living wage is set at a level that allows workers to meet basic needs, and is typically significantly higher than the minimum wage level.22 Despite the added labour cost, living wages also offer a number of advantages for employers including attracting a highly skilled and productive workforce, decreased training and oversight costs, reduced rates of turnover and absenteeism and satisfying customer demand for ethically sourced goods.23

Methods

Design and sampling

Intervention factory

The intervention factory was opened in April 2010 by an American apparel company interested in creating a new model of sweatshop free clothing manufacturing. The intervention factory employs a total of 130 workers and is located in a free trade zone in the Dominican Republic. The factory was previously owned by another clothing manufacturer that had employed up to 3000 workers before closing several years prior to the living wage intervention. When this factory was closed down and abandoned, many members of the local workforce lost their jobs and were forced to choose between unemployment or commuting to minimum wage jobs in distant cities. When the new owners reopened the factory and hired a local workforce, they committed to paying a living wage, creating a positive work environment and respecting rights to collective bargaining.

The living wage was calculated by an independent labour rights organisation using the local cost of supporting a family of four. The living wage is approximately 3.5 times the free trade zone minimum wage, but likely even greater than stated, given that workers often do not receive even the local minimum wage to which they are entitled due to wage underpayment, improper overtime payments, fines and deductions, withholding of wages for long periods of time, job placement fees and lack of severance payments when plants close.24 This wage increase was exogenous because factory job applicants were not told about the living wage when they were hired in December 2009, and they expected to be paid the usual minimum wage. The living wage was not announced until February 2010, shortly before the factory opened. Later hires are likely to have known about the living wage intervention, but they were not included in our sample.

The living wage intervention also included key workplace improvements such as rights to organise, higher labour standards, work hour restrictions, no tolerance for verbal, physical, or sexual abuse, rules intended to prevent child labour, and occupational health and safety upgrades. Management has a collaborative relationship with the leadership of the local labour union, who participate in the factory management, production planning and professional and personal development programmes for employees. All new staff members, including supervisors and managers, receive training and orientation on workers’ rights. The factory's compliance with these standards is verified through intensive on-the-ground monitoring of the factory by the same independent labour rights organisation that calculated the living wage.

Comparison factory

The comparison factory was selected because it was an apparel factory of similar size to the intervention factory and was located less than 50 miles from the intervention factory. The comparison factory was also in a free trade zone, which implies a similar economic climate in terms of taxes, duties and import/export regulations. Working conditions reflect the predominant model of apparel assembly for export seen throughout factories in the Dominican Republic.

Final sample

The final sample consisted of 204 workers, 99 workers from the initial batch of hires at the intervention factory and 105 workers from the comparison factory. Eligibility was limited to workers being paid an hourly wage; higher paid managerial, administrative and technical employees were ineligible. At the intervention factory, surveys were completed with 105 of the 107 eligible workers. Six of the 105 participants (6%) were excluded from the analyses because they had stopped working during the follow-up period. At the comparison factory, 132 of 180 total workers were eligible to complete surveys based on the same eligibility criteria. Of these 132 workers, 105 completed surveys, 18 were untraceable, 5 were not working, 3 were absent on the day of the survey, and 1 refused to participate. A priori power calculations were conducted to determine that the sample size was large enough to detect a two unit or greater difference in depressive symptoms between groups using an assumed power of 80% and a significance level of 5%.

Data collection and measures

The survey data presented here were collected in July and August of 2011, 15–16 months after the intervention factory opened. Consultation with local representatives ensured that the interpretation of the interview questions matched the original intent in English. Interviewers attempted to contact all eligible workers. Union representatives and factory management provided assistance in locating survey participants. Interviews were conducted in Spanish by a third party survey agency and lasted approximately 2 h. The survey agency explained the purpose of the survey, the voluntary and confidential nature of study participation, and obtained signed consent from all participants. Workers at both factories were interviewed in their homes on Friday afternoons and weekends to avoid disrupting the workweek.

Depression

The primary outcome of interest was depressive symptoms, measured using the Spanish version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item questionnaire with scores that range from 0 to 60.25 Items assess the frequency of symptoms during the past week, including depressed mood, loss of interest and/or pleasure in activities, fatigue, sleep and appetite disturbances. The CES-D has been validated for use in diverse Spanish speaking populations.18 26 We examined workers’ total scores on the 20-item measure and their scores for the four subscales: depressive symptoms, somatic symptoms, lack of positive affect and interpersonal relations. Of the 20 items, up to 4 were imputed where necessary using the mean of the non-missing responses for that individual; only four individuals (<2% of total) had scores with imputed values. A total score of 16 has frequently been used as the cut-off indicating clinical levels of distress in the USA, although research from Mexico suggests that a higher cut-off score may be more culturally appropriate for identifying clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms in Spanish speaking populations.26 We also used a more conservative CES-D cut-off score of 20 (75th centile).

Covariates

Demographic (gender, age, years of work experience), education and health during the first 15 years of life were obtained via self-report. Adult height reflects childhood health and general population health,27 and was measured using standardised methods.28

Data analysis

We examined covariate balance between workers in the intervention and comparison factories to determine how well matched the workers were on sociodemographic variables that could affect depressive symptoms. We then compared the group means using t tests and tests of proportions. We analysed the continuous CES-D measure using multivariable, linear, ordinary least squares regression, regressing the CES-D score on the independent variable of interest, factory site. We statistically controlled for the following factors that occurred prior to intervention exposure: age, gender, current height, highest level of education, childhood health and total years of work experience. Possible interaction effects for gender, education and childhood health were also examined. To check the robustness and clinical significance of our findings, we estimated relative risks using the Poisson likelihood and robust SEs with dichotomous CES-D outcomes based on clinical cut-offs of 16 and 20.29 Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA V.10.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Workers at the intervention factory were not statistically different from workers at the comparison factory for age, childhood health and total years of work experience (table 1). Workers at the intervention factory were, however, more likely to be female, taller and have completed at least secondary school.

Table 1.

Description of preintervention population variables in intervention and comparison factories

| Category | Subcategory | Comparison factory N=105 |

Intervention factory N=99 |

p Value for difference† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean±SD) | 34.19±8.42 | 34.95±4.98 | 0.437 | |

| Gender (%) | Men | 46 (43.8) | 24 (24.2) | 0.003** |

| Women | 59 (56.2%) | 75 (75.8%) | ||

| Height (cm, Mean±SD) | Men | 168±6 | 171±4 | 0.028* |

| Women | 157±5 | 159±5 | 0.019* | |

| Highest level of education (%) | Primary or lower | 56 (53.3) | 25 (25.3) | 0.000** |

| Secondary or higher | 49 (46.7) | 74 (74.7) | ||

| Childhood Health (%) | Fair or poor | 33 (31.4) | 39 (39.4) | 0.234 |

| Good or excellent | 72 (68.6%) | 60 (60.6%) | ||

| Total years of work experience (Mean±SD) | 13.4±7.62 | 13.2±5.43 | 0.840 | |

*=p<0.05; **=p<0.01.

†Tests of difference conducted using t test or test of proportions where appropriate.

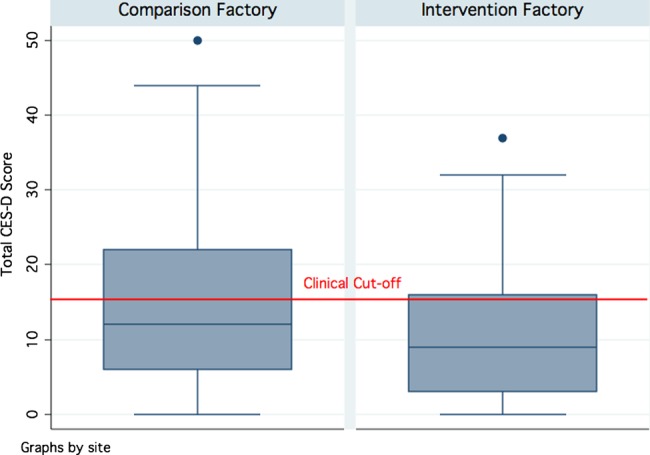

Workers at the intervention factory had lower mean depressive symptom scores than workers at the comparison factory (10.6±9.3 vs 14.7±11.6, p=0.007) (table 2); depressive symptom scores had a much wider distribution among workers at the comparison factory when compared with the intervention factory (figure 1). Using the standard CES-D cut-off score of 16, 23% of workers at the intervention factory reported clinical levels of depressive symptoms compared to 40% of workers at the comparison factory (p=0.010). Using a more conservative CES-D cut-off score of 20, 17% of workers at the intervention factory and 29% of workers at the comparison factory reported clinical levels of depressive symptoms (p=0.053).

Table 2.

Summary of depression variables, unadjusted, in intervention and comparison factories

| CES-D Scores | Comparison mean (SD) | Intervention mean (SD) | p Value for difference† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous outcomes | |||

| Full depression scale (0–60) | 14.7 (11.6) | 10.6 (9.3) | 0.007** |

| Depression subscales | |||

| Depressed affect/mood (0–21) | 4.3 (4.7) | 3.0 (3.5) | 0.031* |

| Somatic symptoms (0–21) | 5.4 (4.5) | 4.1 (3.8) | 0.023* |

| Lack of positive affect (0–12) | 4.0 (2.7) | 2.9 (2.7) | 0.004** |

| Interpersonal relations (0–6) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.077 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Dichotomous with cut-off | |||

| Depression score >16 | 42 (40) | 23 (23) | 0.010* |

| Depression score >20 | 30 (29) | 17 (17) | 0.053 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01.

†Tests of difference conducted using t test or test of proportions where appropriate.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale.

Figure 1.

Distribution of total CES-D scores for comparison and intervention factory workers. Boxes denote the IQR between the first and third quartiles (25th and 75th centiles, respectively) and the blue line inside denotes the median. Whiskers denote the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times IQR from the first and third quartiles, respectively. Circles denote outliers beyond the whiskers. The red line denotes the total CES-D score of 16 that has frequently been used as the cut-off indicating clinical levels of distress. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale.

In adjusted analyses (table 3), working at the intervention factory was significantly associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms (β=−5.4 points, 95% CI −8.5 to −2.3, p=0.001) while controlling for age, gender, height, education, childhood health and work experience. The treatment effect persisted for all four CES-D subscales: depressed affect, somatic symptoms, lack of positive affect and interpersonal relations. No significant treatment interactions were identified with gender, education or childhood health for the summary score or for the subscales. Working in the intervention factory was also associated with a reduced risk of clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms among workers. Using the standard CES-D cut-off score of 16, workers at the intervention factory had an adjusted 47% reduced risk of clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms (IRR=0.53, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.83, p=0.006). Using a more conservative CES-D cut-off score of 20, workers at the intervention factory had an adjusted 48% reduced risk of clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms (IRR=0.52, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.92, p=0.024).

Table 3.

Effects of living wage factory on depression variables, adjusted for covariates†

| CES-D Scores | Effect (β)‡ | (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous outcomes | |||

| Full depression scale (0–60) | −5.4 | (−8.5 to −2.3) | 0.001** |

| Depression subscales | |||

| Depressed affect/mood (0–21) | −1.9 | (−3.1 to −0.7) | 0.002** |

| Somatic symptoms (0–21) | −1.9 | (−3.1 to −0.7) | 0.002** |

| Lack of positive affect (0–12) | −1.1 | (−2.0 to −0.3) | 0.007** |

| Interpersonal relations (0–6) | −0.5 | (−0.8 to −0.1) | 0.020* |

| IRR§ | (95% CI) | ||

| Dichotomous with cut-off | |||

| Depression score >16 | 0.53 | (0.34 to 0.83) | 0.006** |

| Depression score >20 | 0.52 | (0.30 to 0.92) | 0.024* |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01.

†Covariates: Age, gender, height, education, childhood health, work experience.

‡Adjusted average treatment effect sizes are OLS regression coefficients (β) for the continuous CES-D scores.

§Adjusted relative risk estimates are Poisson regression coefficients for a dichotomous outcome based on CES-D cut-off scores.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale.

Discussion

In this study, we measured the effects of an approximately 350% difference in wages and workplace improvements on depression symptoms of apparel workers in the Dominican Republic. Workers at the intervention factory had significantly lower levels of depression symptoms than workers at the comparison factory in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The treatment effect was also seen across all four CES-D subscales: depressed mood, somatic symptoms, lack of positive affect and interpersonal relations. Workers at the intervention factory also had a 47% reduced risk of clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms as compared with workers at the comparison factory.

This paper adds to the small body of existing research investigating how reductions in poverty and workplace improvements may lead to improved mental health. The living wage component of the intervention represents a substantially larger income shock than existing income interventions. Unconditional and conditional cash transfers tend to be around 5–25% of participants’ household expenditures, while loans from MFIs are often ∼40% of borrower's gross monthly income.16 17 The large size of the living wage may help to explain the magnitude of our findings. The other major component of the living wage intervention focused on workplace improvements, including high labor standards, worker and union empowerment, occupational health and safety improvements and professional development programmes for employees. Previous research suggests that workplace improvements and empowerment may lead to improved health outcomes,30 31 and these aspects of the intervention likely contributed substantially to the differences in depressive symptoms between the two sites. Given our methodology, it is not possible to determine the degree to which the wage increase and workplace improvement components of the intervention individually contributed to the outcomes.

To put these findings into context, the difference in depressive symptoms associated with the living wage intervention can be compared to the effects of medical and psychotherapeutic treatment for depression. Randomised controlled trials assessing antidepressant medications have found they typically offer a two to four point advantage over placebo as assessed by a standard outcome measure such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,32 or an estimated 10–15% difference in response or remission rates.33 The efficacy of psychotherapy is comparable to that of antidepressants.34 35

The major limitation to our study is the lack of baseline data from both sites, which would have allowed for longitudinal analysis. Given our cross-sectional methodology, we can associate the differences in depressive symptoms at the two factories with the living wage intervention, but cannot demonstrate causality. Another important limitation to the interpretation and generalisability of our findings is the non-randomised assignment of workers to intervention and comparison factories, due to ethical and logistical constraints. This unique intervention was initiated by a private manufacturing company opening a new model of apparel factory at a predetermined site, therefore some differences between workers at the intervention and control sites are to be expected. Although the two groups were generally similar, intervention factory workers were more likely to be women, to be taller, and to have achieved at least a secondary education than workers at the comparison factory.

Our quasi-experimental design is justified by the fact that workers at the intervention factory were hired in December 2009, with no knowledge of the living wage intervention until it was announced in February 2010. It is plausible that these workers hired at the intervention factory started with higher than average levels of depressive symptoms due to the closure of the town's previous major manufacturing employer and the psychological impact of being unemployed or commuting long distances. However, it is also possible that word of the dramatically increased wages spread locally to prospective employees during the hiring period, potentially attracting more motivated workers who may have been less depressed to begin with. While we selected a comparison factory that was as similar as possible to the intervention factory and controlled for all measured variables in our adjusted analyses, our study does not benefit from the same strength of causal inference as an experimental design.

We find that providing a living wage and workplace improvements to improve income and well-being in a disadvantaged population may have a ripple effect of also reducing depressive symptoms. The large difference in levels of depressive symptoms between the two factories included in our study suggests that earning a living wage in a positive work environment may have a profoundly positive effect on mental health. The magnitude of this difference is significantly greater than the largely mixed effects of other income interventions on depression, and more in line with treatment effects of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy.

The findings in this study will have the potential to enhance our understanding of the impact of economic and employment interventions on depression in the poor. This contribution is especially relevant to low-income settings where targeted approaches to improving mental health are often infeasible given the large burden of mental illness and limited availability of specialised services. In this setting, maximising the positive physical and mental health influences of economic development programmes and working condition improvements is a promising strategy. Even in the US, where the prevalence of mental disorders remains very high despite massive expenditure,36 wage and workplace interventions may be valuable for improving mental health and offer new avenues for future health policy efforts.

Further research is needed to see whether the living wage intervention's association with decreased levels of depression symptoms will continue to grow with time, level off or possibly diminish. Replication of this study is needed with larger sample sizes, longitudinal data collection and in different contexts. Future research is also needed to disentangle the effects of the wage increase and workplace improvement components of the intervention and to better understand the mechanisms responsible for the differences in depressive symptoms. Finally, it will be important to examine potential synergistic effects of living wage intervention components specifically targeting mental health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Cecilia Acevedo, Emily Flynn, Melissa Hidrobo.

Footnotes

Contributors: KBB analysed the data and wrote the paper. JCL and ML assisted with data cleaning and reviewed drafts. KS-G contributed to interpretation of results and reviewed drafts. SA-M assisted in the design and implementation of the survey and reviewed drafts. DHR and LCHF conceptualised and designed the study, contributed to acquisition, analysis and interpretation of results, and reviewed drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Funding for this research was obtained from UC Berkeley (pilot funds), UC San Francisco/Berkeley Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholars Program (pilot funds), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant number: R21 HD056581).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California at Berkeley and signed consent was obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Transparency declaration: We attest that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported. We have full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M et al. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:90 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:216–26. 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00273-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001547 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surkan PJ, Kennedy CE, Hurley KM et al. Maternal depression and early childhood growth in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:607–15. 10.2471/BLT.11.088187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachs TD, Black MM, Engle PL. Maternal depression: a global threat to children's health, development, and behavior and to human rights. Child Dev Perspect 2009;3:51–9. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00077.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel V, Kleinman A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:609–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel V, Lund C, Hatherill S et al. Mental disorders: equity and social determinants. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. World Health Organization, 2010:115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:517–28. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S et al. Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011;378:1502–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M et al. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007;370:878–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huston AC, Duncan GJ, McLoyd VC et al. Impacts on children of a policy to promote employment and reduce poverty for low-income parents: new hope after 5 years. Dev Psychol 2005;41:902 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gennetian LA, Miller C. Children and welfare reform: a view from an experimental welfare program in Minnesota. Child Dev 2002;73:601–20. 10.1111/1467-8624.00426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris P, Michalopoulos C. Findings from the self-sufficiency project: effects on children and adolescents of a program that increased employment and income. J Appl Dev Psychol 2003;24:201–39. 10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00045-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGroder SM, Moore KA, Zaslow MJ. National Evaluation of Welfare-to-work Strategies: Impacts on Young Children and Their Families Two Years After Enrollment: Findings from the Child Outcomes Study: Summary Report. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forget EL. New questions, new data, old interventions: the health effects of a guaranteed annual income. Prev Med 2013;57:925–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paxson C, Schady N. Does money matter? The effects of cash transfers on child development in rural Ecuador. Econ Dev Cult Change 2010;59:187–229. 10.1086/655458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macours K, Schady N, Vakis R. Can conditional cash transfer programs compensate for delays in early childhood development? Draft paper presented at IDB, Washington DC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozer EJ, Fernald LC, Weber A et al. Does alleviating poverty affect mothers’ depressive symptoms? A quasi-experimental investigation of Mexico's Oportunidades programme. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1565–76. 10.1093/ije/dyr103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plagerson S, Patel V, Harpham T et al. Does money matter for mental health? Evidence from the Child Support Grants in Johannesburg, South Africa. Global Public Health 2011;6:760–76. 10.1080/17441692.2010.516267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohindra K, Haddad S, Narayana D. Can microcredit help improve the health of poor women? Some findings from a cross-sectional study in Kerala, India. Int J Equity Health 2008;7:2 10.1186/1475-9276-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masud Ahmed S, Chowdhury M, Bhuiya A. Micro-credit and emotional well-being: experience of poor rural women from Matlab, Bangladesh. World Dev 2001;29:1957–66. 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00069-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams S, Neumark D. The economic effects of living wage laws a provisional review. Urban Aff Rev 2004;40:210–45. 10.1177/1078087404269540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kline JM. Alta Gracia: Branding Decent Work Conditions. Will College Loyalty Embrace “Living Wage” Sweatshirts? Washington, DC: Georgetown University, 2010. https://georgetown.box.com/s/wntf7bah8ls1vbbg6ar3 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dirnbach E. Weaving a stronger fabric: organizing a global sweat-free apparel production agreement. Working USA 2008;11:237–54. 10.1111/j.1743-4580.2008.00200.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salgado de Snyder N, Maldonado M. Psychometric characteristics of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adult Mexican women from rural areas. Salud Publica Mexico 1993;36:200–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steckel RH. Biological measures of the standard of living. J Econ Perspect 2008;22:129–52. 10.1257/jep.22.1.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cogill B. Anthropometric indicators measurement guide. Washington: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, 2003:1–92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallerstein N. What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe's Health Evidence Network, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown GD. The global threats to workers’ health and safety on the job. Social Justice, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1960;23:56 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thase ME. The small specific effects of antidepressants in clinical trials: what do they mean to psychiatrists? Curr Psychiatry Rep 2011;13:476–82. 10.1007/s11920-011-0235-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL et al. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 2013;12:137–48. 10.1002/wps.20038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spielmans GI, Berman MI, Usitalo AN. Psychotherapy versus second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis 2011;199:142–9. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31820caefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson C, Lozano R, Naghavi M et al. The burden of mental disorders in the USA: new tools for comparative analysis of health outcomes between countries. Lancet 2013;381:S10 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61264-723452933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]