Abstract

Objective

Peppermint oil (PMO) has been used to treat abdominal ailments dating to ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. Despite its increasing paediatric use, as in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) treatment, the pharmacokinetics (PK) of menthol in children given PMO has not been explored.

Design and setting

Single-site, exploratory pilot study of menthol PK following a single 187 mg dose of PMO. Subjects with paediatric Rome II defined (IBS; n=6, male and female, 7–15 years of age) were enrolled. Blood samples were obtained before PMO administration and at 10 discrete time points over a 12 h postdose period. Menthol was quantitated from plasma using a validated gas chromatography mass spectrometry technique. Menthol PK parameters were determined using a standard non-compartmental approach.

Results

Following a dose of PMO, a substantial lag time (range 1–4 h) was seen in all subjects for the appearance of menthol which in turn, produced a delayed time of peak (Tmax=5.3±2.4 h) plasma concentration (Cmax=698.2±245.4 ng/mL). Tmax and Tlag were significantly more variable than the two exposure parameters; Cmax, mean residence time and total area under the curve (AUC=4039.7±583.8 ng/mL×h) which had a coefficient of variation of <20%.

Conclusions

Delayed appearance of menthol in plasma after oral PMO administration in children is likely a formulation-specific event which, in IBS, could increase intestinal residence time of the active ingredient. Our data also demonstrate the feasibility of using menthol PK in children with IBS to support definitive studies of PMO dose–effect relationships.

Keywords: PAEDIATRICS, THERAPEUTICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An initial description of the concentration versus time relationship for menthol following administration of a proprietary peppermint oil (PMO) formulation to treat paediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

A basis for the design of future paediatric investigations of PMO to characterise the exposure–response relationship for menthol in children with IBS.

A small study cohort which, while providing descriptive information regarding the clinical pharmacology of menthol from PMO in paediatric patients with IBS, may not reflect the true population variability in the dose versus exposure relationship.

Introduction

Peppermint oil (PMO) (Menthae piperitae aetheroleum) is obtained by steam distillation from the fresh leaves of peppermint (Mentha piperita L). The major constituents of PMO include the terpenes (−) menthol (30–50%), (−) menthone (14–32%), (+) isomenthone (1.5–10%), (−) menthyl acetate (2.8–10%), (+) menthofuran (1.0–9.0%), and 1,8-cineol (3.5–14%). As reviewed by Grigoleit and Grigoleit,1 the pharmacologically active ingredient of PMO is menthol that in nature exists as a pure stereoisomer (1R,2S,5R)-2-Isopropyl-5-methylcyclohexanol).

Through its ability to act as a calcium antagonist, menthol appears to have a spasmolytic effect in the gastrointestinal tract. Consequently, PMO has been used to treat abdominal ailments in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome,2 and anecdotal evidence of its purported efficacy abounds to this day. A review and several meta-analyses of randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trials in adults have demonstrated that PMO is effective in reducing abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).1 3–7 However, in children with IBS, there is a dearth of information restricted to a single small (n=42), double blind, placebo-controlled trial.7 Nonetheless, the use of PMO as an adjunctive measure to treat children with IBS continues to evolve in clinical practice despite the lack of any information pertaining to the impact of age and/or disease state on its pharmacodynamics (PDs) or pharmacokinetics (PKs). Thus, dosing remains empiric in paediatric patients and adults, where a range in daily doses of more than 2.5-fold has been reported.1

Given the increasing use of PMO in paediatric patients with IBS and the potential for developmental changes to influence the PKs and PDs of drugs,8 we conducted an exploratory, pilot PK study of menthol following the administration of a proprietary formulation of PMO in a cohort of paediatric patients with IBS. The primary objective of this study was to examine the concentration versus time profile of menthol following a single PMO dose and to describe its apparent PK.

Methods

Patients

We performed a single-site, proof-of-principle exploratory study of menthol PKs following a single 187 mg oral dose of PMO (Colpermin capsule; Tillotts Pharma, Rheinfelden, Switzerland). Patients with paediatric Rome III defined IBS (n=6), who had no intercurrent illness or recent change in IBS symptoms, were enrolled into a protocol approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Children initially were identified by review of medical records. They were screened by telephone to be sure they qualified and that IBS symptoms were current. They were otherwise healthy. Absence of illness was assessed via history and physical examination at the time of the study visit. No participant was receiving therapeutic medications and/or natural products known to influence the activity of either hepatic drug metabolism (ie, no enzyme inducers or inhibitors) or renal drug clearance. Finally, other than an existing diagnosis of IBS, no study participant had a history of an abnormality or surgery of the gastrointestinal tract.

All study participants were enrolled by informed parental consent and when appropriate (eg, >6 years of age), by patient assent. Informed consent was documented prior to performing any study-related procedure.

Drug administration, sampling and sample handling

The clinical phase of this study was conducted in strict accordance with good clinical practice principles. Prior to being admitted to the Metabolic Research Unit (MRU) at the Children's Nutrition Research Center, study participants were fasted from midnight immediately preceding the morning of admission (ie, overnight). Following the history, physical examination and recording of vital signs (temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate, seated blood pressure), a venous cannula (21 gauge) was aseptically placed in a large vein either in the dorsum of the hand or on the volar surface of the lower arm to facilitate obtaining repeated blood samples to support the PK objectives of the study. The cannula was secured and its patency maintained through periodic flushing of the dead space with sterile 0.9% sodium chloride.

At approximately 09:00, subjects received a single oral dose of PMO given as a commercially available, proprietary, non-prescription product (Colpermin, each capsule containing approximately 83.0 mg of menthol as a constituent of PMO) followed by 120 mL of water at 25°C. Immediately prior to administration of the test article, a blood sample (2.0 mL) was obtained. After PMO administration, repeated blood samples (2.0 mL each) were obtained directly into green top glass tubes containing sodium heparin (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, East Rutherford, New Jersey, USA) at the following postdose time points: 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h. At 2 h after PMO administration, participants were given a standardised meal. Throughout the 12 h study period, participants were restricted from any strenuous physical exercise. After completion of the final (12 h) sample, vital signs were reassessed, the venous cannula was removed and the insertion site evaluated for redness, swelling and/or bruising. Study participants were then discharged from the MRU and received a follow-up call from a clinical research coordinator, approximately 24 h thereafter, to specifically assess/evaluate any potential adverse effects.

Immediately following collection of a given blood sample, it was mixed by gentle inversion and the tube immediately placed at 4°C. At 4 h intervals, blood samples were centrifuged (2500g for 10 min at 4°C). The resultant plasma from each tube then was immediately transferred into a clean, screw-capped polypropylene tube and immediately frozen at −80°C. Samples were maintained at 2–8°C while handling so as to minimise evaporative loss of any volatile compounds contained therein.

Analytical

Total (ie, conjugated and unconjugated) menthol in plasma was measured by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS), as described in previous methods, with several minor modifications.9 10 Briefly, to 0.5 mL of the patient's heparinised plasma or controls or calibrators, 20 µL internal standard (menthol-d4, 10 µg/mL), 25 µL β-glucuronidase (90 000 U/mL), and 10 µL sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.8) were added. The mixture was incubated overnight in air-tight tubes in 37°C water bath and into each tube, 150 µL 0.4 M phosphate buffer (pH 4.8) was added. Menthol was extracted in 0.5 mL methylene chloride by rocking the tubes for 5 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 2000g for 5 min. The methylene chloride layer was transferred to an auto-sampler vial and a 2 µL extract was injected onto the GC-MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) installed with ZB-1MS 15×250×0.25 µm column. Ions (m/z) monitored for quantification and identification were 138, 123, 95 for menthol and 142, 127, 99 for menthol-d4. The data were analysed using Target Software (Thru-Put Systems, Orlando, Florida, USA). The quantitative ions were used to construct standard curves of the peak area ratios (calibrator/internal standard pair). The assay was linear within the range of concentrations evaluated 5–1000 ng/mL (r2>0.99). For all standards, the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variations (CVs) were <10%.

PK data analysis

Menthol plasma concentration versus time data were evaluated using a model independent approach. Individual Cmax and Tmax were obtained by direct examination of the plasma concentration versus time profile. The area under the plasma concentration versus time curve during the sampling period (AUC0-n) was calculated using the mixed log-linear method where ‘n’ refers to the final sampling time with quantifiable menthol concentrations. The terminal elimination rate constant (λz) was estimated using an iterative least-squares regression algorithm when a sufficient number of postpeak concentrations were available to support a reliable estimation of the parameter. When possible, the total AUC (AUCtot) was extrapolated to infinity by dividing λz into the predicted plasma concentration at the end of the sampling interval. As a subset of our patients (n=3) did not have >3 post-Cmax plasma concentrations, there was significant uncertainty associated with the estimation of λz and consequently, the PK parameters that rely on the terminal rate constant (eg, AUC to infinity (AUC0-∞), apparent oral clearance (Cl/F), and apparent volume of distribution at steady-state (Vss/F)) are not reported. Menthol PK data were examined using standard descriptive statistics. A priori determination of statistical power was not considered given that this was the first PK study performed in a paediatric cohort; the goal of this exploratory study was descriptive and no comparisons (ie, within group or between group) of PK data were undertaken. All analyses were performed in Kinetica V.5.1 (Thermo Scientific) and SPSS V.20 (IBM SPSS).

Results

All six participants completed the study without experiencing any apparent adverse events. The study cohort consisted of four female and two male patients. Their age range was 7–12 years (10.3±1.9 years.), and their body weights ranged from 26.6 to 58.2 kg (45.2±11.5 kg). None of the participants had a height or weight which was outside of the 5–95th centile for age.

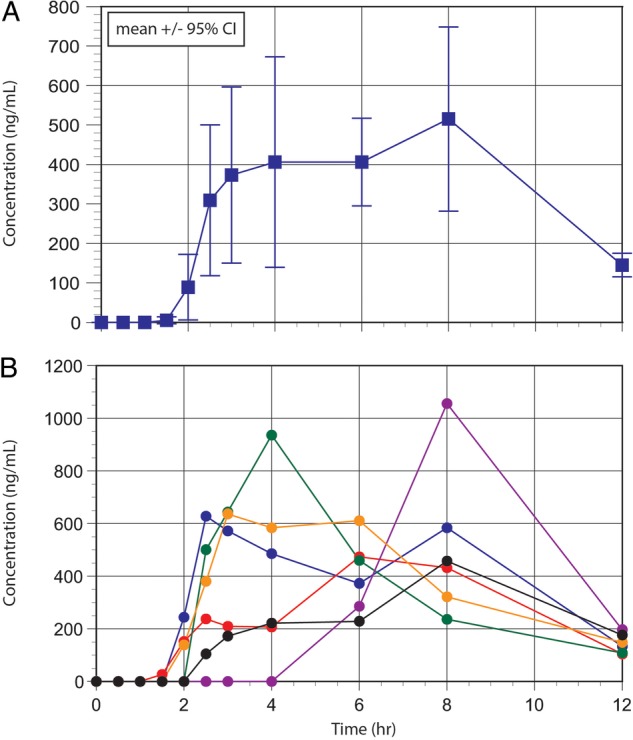

The composite (mean±95% confidence limits) and individual plasma menthol concentration versus time data are shown in panels A and B of the figure 1, respectively. Considerable intersubject variability in the plasma concentration versus time profiles was apparent with all participants in the cohort. Individual PK parameters for menthol are provided in table 1. The time of appearance (Tmax) for apparent peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) ranged from 2.5 to 8 h following a lag time (Tlag) which ranged from 1.5 to 4 h. Absolute Cmax values ranged from 458 to 1056 ng/mL, which when corrected to a weight-adjusted menthol dose received by each child ranged from 255 to 470 ng/mL per 1 mg/kg (ie, an approximate 1.8-fold difference). The dose normalised systemic menthol exposure reflected by the area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC per mg/kg dose) varied over an approximate twofold range (1464.1 to 2941.1 ng/mL×h). Given the marked delay in the appearance of menthol in plasma after a PMO dose, sufficient postpeak plasma concentrations to reliably estimate an apparent elimination rate constant (λz) and elimination half-life were not available in all participants. Consequently, the non-compartmental parameter mean residence time (MRT; a time representing elimination of approximately 60% of a given dose from the body) was determined using statistical moment theory and ranged from 6.4 to 9.4 h (table 1).

Figure 1.

Mean (± 95% confidence interval) plasma concentration vs. time data for menthol in a cohort of six children with Irritable Bowel Syndrome given a single oral dose of peppermint oil containing approximately 83.0 mg of menthol [top panel] and individual plasma menthol concentration vs. time data [bottom panel].

Table 1.

Individual menthol pharmacokinetic parameters

| Participant | Menthol dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (ng/mL) | Cmax (ng/mL per mg/kg dose) | Tmax (h) | Tlag (h) | AUClast (ng/mL×h per mg/kg dose) | AUCtot (ng/mL×h per mg/kg dose) | MRT (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MentPK-01 | 1.4 | 628 | 445.1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2941.1 | 3199.2 | 7.0 |

| MentPK-02 | 1.5 | 474 | 325.0 | 6 | 1 | 2045.6 | 2245.9 | 7.5 |

| MentPK 03 | 2.0 | 936 | 470.5 | 4 | 2 | 1951.4 | 2137.1 | 6.4 |

| MentPK 04 | 3.1 | 1056 | 342.1 | 8 | 4 | 1198.4 | 1350.5 | 9.1 |

| MentPK 05 | 1.9 | 637 | 332.8 | 3 | 1.5 | 2107.2 | 2434.8 | 7.4 |

| MentPK 06 | 1.8 | 458 | 255.5 | 8 | 2 | 1464.1 | 1879.5 | 9.4 |

AUC, area under the plasma concentration versus time curve; Cmax, apparent peak plasma concentration; MRT, mean residence time; PK, pharmacokinetic; Tlag, apparent lag time between PO administration and appearance of menthol in plasma; Tmax, time of Cmax.

A summary of the PK parameters (mean, SD and 95% CIs) is provided in table 2. As reflected by the values for the CV for each of the parameters, the least variability was observed for MRT (CV=15.4%) and AUCtot (14.4%).

Table 2.

Summary of menthol pharmacokinetic parameters

| Parameter | mean±SD | 95% CI | CV% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 698.2±245.4 | (501.8 to 894.6) | 35.1 |

| Cmax (ng/mL per mg/kg) | 361.8±80.8 | (297.2 to 426.5) | 22.3 |

| Tmax (h) | 5.3±2.4 | (3.3 to 7.2) | 45.3 |

| Tlag (h) | 2.0±1.0 | (1.2 to 2.8) | 50.0 |

| AUClast (ng/mL×h) | 3562.0±616.7 | (3068.5 to 4055.4) | 17.3 |

| AUC last (ng/mL×h per mg/kg dose) | 1951.3±602.8 | (1468.9 to 2433.7) | 30.9 |

| AUCtot (ng/mL×h) | 4039.7±583.8 | (3572.6 to 4506.9) | 14.4 |

| AUC total (ng/mL×h per mg/kg dose) | 2207.8±613.8 | (1716.7 to 2698.9) | 27.8 |

| %AUC extrapolated | 12.1±5.3 | (7.8 to 16.3) | 43.8 |

| MRT (h) | 7.8±1.2 | (6.8 to 8.8) | 15.4 |

AUC, area under the plasma concentration versus time curve; Cmax, apparent peak plasma concentration; CV, coefficient of variation MRT, mean residence time; Tlag, apparent lag time between PO administration and appearance of menthol in plasma; Tmax, time of Cmax.Figure 1 Mean (±95% CI) plasma concentration versus time data for menthol in a cohort of six children with irritable bowel syndrome given a single oral dose of peppermint oil containing approximately 83.0 mg of menthol (top panel) and individual plasma menthol concentration versus time data (bottom panel).

Discussion

The putative active ingredient contained in PMO is menthol, a plant-derived, semivolatile monoterpene. The clinical pharmacology of menthol, with an emphasis on its interaction with sensory neurons (TRP channels), has been recently reviewed.11 The disposition and PKs of menthol derived from the ingestion of PMO in adults also has been reported previously10 12 13 as have the PKs of l-menthol administered directly to the upper gastrointestinal tract.14 In a cohort of 12 adults administered an oral dose of l-menthol (10 and 100 mg), the drug was rapidly metabolised with conversion to a menthol glucuronide that could be measured in plasma and urine.10 In a similar study of 16 adults reported by Mascher et al,13 the apparent time of peak plasma concentration (Tmax) of menthol (measured by GC/MS) following oral administration of a 180 mg dose of enteric coated PMO occurred at approximately 3 h following drug administration. The decline of methanol levels in the plasma was rapid, with an average apparent elimination half-life of approximately 3.5 h.

Recent studies have shown that menthol clearance from plasma is associated with the activity of CYP2A6,15 a polymorphically expressed cytochrome P450 isoform that is responsible for the biotransformation of other xenobiotics such as the primary nicotine metabolite, cotinine,16 and the commonly used antimicrobial agent, metronidazole.17 In the case of cotinine, Dempsey et al16 demonstrated that CYP2A6 genotype (a surrogate for CYP2A6 phenotype), as opposed to age, was the major determinant of cotinine plasma elimination half-life in infants and children. To date, the PK of menthol have not been evaluated or reported in a paediatric patient cohort. Thus, there are no data upon which to base the development of PMO dosing regimens for children or adolescents with IBS to produce desired levels of systemic menthol exposure.

Despite data from only a single available paediatric trial of PMO in children with IBS,7 the substance is being increasingly used either as adjunctive or primary treatment of patients with this disorder based on anecdotal evidence of symptomatic improvement. It is not known whether the potential analgesic effects of menthol in patients with IBS have a central18 and/or local basis. In contrast, the antispasmodic effects appear to be modulated locally as demonstrated by Hiki et al14 in a study where L-menthol was directly sprayed onto gastric mucosa. It is for this reason that the Colpermin formulation of PO is in an enteric-coated solid oral dosage form and designed to release the active ingredients at a pH encountered in the small intestine (ie,>6.5).19

As illustrated in the figure 1, the appearance of menthol in the plasma of all subjects in our cohort was delayed with an average lag time of 2 h, a finding consistent with aggregate data in adults summarised by the manufacturer of our test article.19 This finding is supported to some extent by two earlier studies of the Colpermin product which examined the PKs of menthol in adults using urinary menthol excretion data12 20 and a more recent adult study which examined menthol concentrations in plasma following the administration of a different enteric-coated PMO product (Enteroplant, Spitzner Pharmaceuticals, Ettlingen, Germany).13 Unlike the plasma concentration profile reported by Mascher et al,13 the mean plasma-menthol concentration versus time data in our paediatric study cohort (figure 1; top panel) demonstrated an apparent prolonged absorption time with apparent peak plasma concentrations (Tmax) occurring between 2.5 and 8 h postdose (table 1). Reasons for the delayed Tmax likely reside with formulation-specific factors (ie, delayed release) and potentially, enterohepatic recirculation as menthol undergoes biotransformation by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 (UGT2B7).21 22 The apparent post-Tmax increase in plasma-methanol concentrations in several of our study participants (figure 1, bottom panel) suggests the presence of enterohepatic recirculation.

In contrast to the adult data reported by Mascher et al,13 we were not able to reliably estimate the apparent terminal elimination rate constant (λz) for menthol in our entire patient cohort; namely, patients 2, 4 and 6 where ≤2 post-Cmax plasma concentrations were available for estimation of the parameter. It was for this reason that we chose to use a non-compartmental approach to describe menthol PKs and to examine MRT as a parameter reflecting drug elimination. As noted above, our inability to produce a reliable estimate of λz precluded our reporting reliable estimates for the apparent plasma clearance and/or volume of distribution for menthol. Also, given the prolonged absorption of menthol in our cohort (figure 1), estimation of λz may have produced an errant result consequent to the phenomenon of the ‘flip-flop model’ which occurs when the rate of absorption and/or distribution is slower than the rate of true drug elimination.23 Nonetheless, based on known patterns of ontogeny with regard to the activity of UGT isoforms,8 we would not expect that the apparent elimination half-life of menthol in our study participants (ie, range from 1.6 to 3.0 h in three patients with reliable λz estimates) would be similar to values for this parameter (3.5 to 4.4 h) previously reported from adults.13 A more accurate estimate of λz would have been available in our cohort had we previously had knowledge of the prolonged menthol absorption profile. This would have enabled us revise our blood sampling paradigm to cluster observations between 6 and 18 h postdose and to extend the sampling interval to 24 h.

Despite considerable variability in the plasma-menthol concentration versus time data in our patients (figure 1), the values for the AUCtot and MRT had the smallest coefficients of variation associated with them (table 2). This relatively close agreement in the PK parameters suggested by the coefficients of variation would seemingly support that despite the presence of allelic variants for CYP2A616 and UGT2B722 in the general population, the concentration versus time data for menthol in our cohort did not appear to contain an ‘outlier’ which could have been attributable to one or more of the participants having inherited an allelic variant for either of these genes.

Admittedly, the results from our exploratory study are descriptive and given the small size of the study cohort, may not be generalisable to a larger population of paediatric patients with IBS. The potential value of our findings resides with the provision of preliminary PK data for menthol in paediatric patients that could be used to inform and enrich the design of future trials to explore the link between menthol PK and PDs in patients with IBS or other disorders such as functional dyspepsia. For example, it is widely known that gastroparesis and delayed emptying can be seen in patients with IBS, with gastrointestinal symptoms having an association with the degree of gastroparesis.24 Use of a non-invasive technique, such as ingestion of a small magnetic pill which is capable of providing objective information regarding motility of the entire gastrointestinal tract,25 could enable one to easily explore PK–PD relationships for menthol in patients with IBS. Such information will be critical in objectively determining the effect and efficacy of menthol in the treatment of this disorder in children and adolescents.

Recently, the European Medicines Agency has issued a public statement on the use of herbal medicinal products containing pulegone and menthofuran, two minor constituents (0.5–4.6% and 1–9%, respectively) of M. piperita oils.26 Concerns regarding the potential associations of these compounds and hepatotoxicity in persons with a high daily intake of PMO will likely spawn a renewed interest in this natural product, especially when it is used in a therapeutic context. While the quantitation of pulegone or menthofuran from the plasma samples of our study participants or the test article was beyond the scope of our study, the human health consequences of their presence as ‘contaminants’ of commercially available PMO formulations are not yet known. Nonetheless, the data from our exploratory study of PMO may have utility in future studies designed to evaluate the dose–concentration–effect relationship for PMO and any compounds contained therein.

Conclusions

Our pilot study demonstrates that the PK of menthol, the active ingredient in PMO, can be adequately characterised in paediatric patients with IBS. It is important to recognise that formulation-specific differences between PMO-containing products can markedly influence the plasma–menthol concentration versus time curve. Such differences must be considered in the design of PK-PD studies of menthol in this disorder so as to enable an accurate characterisation of the concentration–effect relationship.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sabine Elkhoury and Alyssa Khan for their help in coordinating the study, and Ms. Judy Peat for performing the quantitation of menthol in patient specimens.

Footnotes

Contributors: GLK designed the pharmacokinetic portion of the study, and assisted in the pharmacokinetic and statistical analysis of data. He also prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. BPC contributed to the design of the clinical study protocol and its submission to the Institutional Review Board. He contributed to the review and writing of the final version of the manuscript. SMA-R conducted the primary pharmacokinetic and biostatistical analysis of the study data. She contributed to the review and writing of the final version of the manuscript. UG was responsible for the development of the bioanalytical method used for the quantitation of menthol from plasma, and provided oversight and quality control for the analysis of patient samples. He also contributed to the review and writing of the final version of the manuscript. RJS contributed to the design of the clinical study protocol, provided oversight for the conduct of the clinical phases of the study, and to the final interpretation of the study data. In addition, he also contributed to the review and writing of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported in part by the Daffy's Foundation (RJS), the USDA/ARS (RJS) under Cooperative Agreement No. 6250-51000-043, and P30 DK56338 which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Disease Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors. This work is a publication of the USDA/ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA, nor does it make mention of trade names.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P. Gastrointestinal clinical pharmacology of peppermint oil. Phytomedicine 2005;12:607–11. 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulbricht C, Costa D, M Grimes Serrano J et al. An evidence-based systematic review of spearmint by the natural standard research collaboration. J Diet Suppl 2010;7:179–215. 10.3109/19390211.2010.486702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD003460 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enck P, Junne F, Klosterhalfen S et al. Therapy options in irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:1402–11. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283405a17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Spiegel BM et al. Effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a2313 10.1136/bmj.a2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittler MH, Ernst E. Peppermint oil for irritable bowel syndrome: a critical review and metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1131–5. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kline RM, Kline JJ, Di Palma J et al. Enteric-coated, pH-dependent peppermint oil capsules for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. J.Pediatr. 2001;138:125–8. 10.1067/mpd.2001.109606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW et al. Developmental pharmacology-drug disposition, action and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1156–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spichiger M, Muhlbauer RC, Brenneisen R. Determination of menthol in plasma and urine of rats and humans by headspace solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography—mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2004;799:111–17. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelal A, Jacob P III, Yu L et al. Disposition kinetics and effects of menthol. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999;66:128–35. 10.1053/cp.1999.v66.100455001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farco JA, Grundmann O. Menthol—Pharmacology of an important naturally medicinal “cool”. Mini-Rev in Med Chem 2013;13:124–31. 10.2174/138955713804484686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somerville KW, Richmond CR, Bell GD. Delayed release peppermint oil capsules (Colpermin) for the spastic colon syndrome: a pharmacokinetic study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1984;18:638–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02519.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mascher H, Kikuta C, Schiel H. Pharmacokinetics of menthol and carvone after administration of an enteric coated formulation containing peppermint oil and caraway oil. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res 2001;51:465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiki N, Kaminishs M, Hasunuma T et al. A phase I study evaluating tolerability, pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of L-menthol in supper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;90:221–8. 10.1038/clpt.2011.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazawa M, Marumoto S, Takahashi T et al. Metabolism of (+) and (-) menthols by CYP2A6 in human liver microsomes. J Oleo Sci 2011;60:127–32. 10.5650/jos.60.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dempsey DA, Sambol NC, Jacob P III et al. CYP2A6 genotype but not age determine cotinine half-life in infants and children. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013;94:400–6. 10.1038/clpt.2013.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce RE, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Sampson MR et al. The role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the formation of 2-hydroxymetronidazole; CYP2A6 is the high affinity (low Km) catalyst. Drug Metab Dispos 2013;41:1686–94. 10.1124/dmd.113.052548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan R, Tian Y, Gao R et al. Central mechanisms or menthol-induced analgesia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012;343:661–72. 10.1124/jpet.112.196717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://www.tillotts.com/tillots-services/case-studies/colpermin (accessed 12 Dec 2014).

- 20.White DA, Thompson SP, Wilson CG et al. A pharmacokinetic comparison of two delayed-release peppermint oil preparations, Colpermin and Mintec, for treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Pharmaceut 1987;40:151–5. 10.1016/0378-5173(87)90060-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhasker CR, McKinnon W, Stone A et al. Genetic polymorphism of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 (UGT2B7) at amino acid 268: ethnic diversity of alleles and potential clinical significance. Pharmacogenetics 2000;10:679–85. 10.1097/00008571-200011000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi T, Caldwell J, Farmer PB. Metabolic fate of [3H]-l-menthol in the rat. Drug Metab Dispos 1994;22:616–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritschel WA, Kearns GL. Handbook of basic pharmacokinetics. 7th edn Washington DC: American Pharmaceutical Association, 2009:4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong GK, Shulman RJ, Malaty HM et al. Relationship of gastrointestinal symptoms and psychosocial distress to gastric retention in children. J Pediatr 2014;165:85–91. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedsund C, Joensson IM, Gregersen T et al. Magnet tracking allows assessment of regional gastrointestinal transit times in children. Clin Exper Gastroenterol 2013;3:201–8. 10.2147/CEG.S51402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public statement on the use of herbal medicinal products containing pulegone and menthofuran, European Medicines Agency, EMA/HMPC/138386/2005 Rev. 1; 24 November 2014.