Abstract

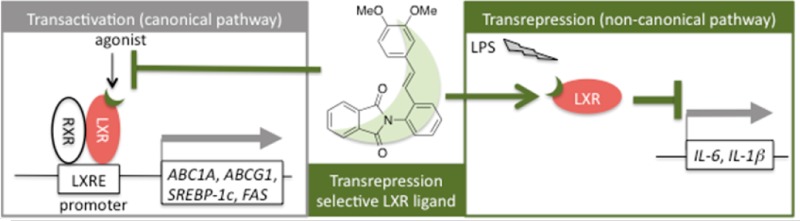

Anti-inflammatory effects of liver X receptor (LXR) ligands are thought to be largely due to LXR-mediated transrepression, whereas side effects are caused by activation of LXR-responsive gene expression (transactivation). Therefore, selective LXR modulators that preferentially exhibit transrepression activity should exhibit anti-inflammatory properties with fewer side effects. Here, we synthesized a series of styrylphenylphthalimide analogues and evaluated their structure–activity relationships focusing on LXRs-transactivating-agonistic/antagonistic activities and transrepressional activity. Among the compounds examined, 17l showed potent LXR-transrepressional activity with high selectivity over transactivating activity and did not show characteristic side effects of LXR-transactivating agonists in cells. This representative compound, 17l, was confirmed to have LXR-dependent transrepressional activity and to bind directly to LXRβ. Compound 17l should be useful not only as a chemical tool for studying the biological functions of LXRs transrepression but also as a candidate for a safer agent to treat inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Liver X receptor, transrepression, inhibition of interleukin-6 level, styrylphenylphthalimide

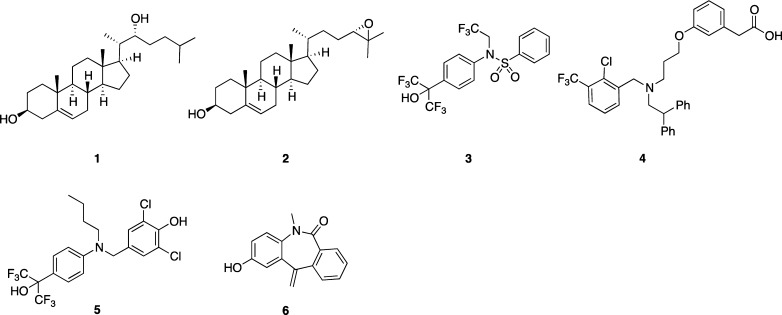

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are ligand-dependent transcription factors that regulate multiple biological functions, including homeostasis, metabolism, and the immune system. Forty-eight kinds of NRs have been identified in humans. Among them, liver X receptors (LXRs) consist of two subtypes, LXRα and LXRβ, which both form heterodimers with retinoid X receptor (RXR). LXRα is highly expressed in liver, intestine, adipose tissue, and macrophages, while LXRβ is present ubiquitously in organs and tissues.1 The physiological ligands for LXRα/β are oxysterols, including 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (1) and 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol (2) (Figure 1).2,3 Upon binding of an agonist to the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of LXR, the LXR/RXR heterodimer binds to LXR response elements (LXRE) in promoter regions of specific genes, and helix 12 (H12) in the LBD adopts a conformation that closes the ligand binding pocket and forms a groove to which coactivators can bind, allowing gene transcription to occur.4 The products of LXRE-regulated genes,2 such as ABCA1, ABCG1, ABCG5, ABCG8, ApoE, and GLUT4, are involved in lipid metabolism, reverse cholesterol transport, and glucose transport, so LXRs are considered to be potential drug targets for atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.5 The ligand-mediated activation of LXRE-dependent gene transcription is called transactivation.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of endogenous LXR ligands (1 and 2), synthetic LXR ligands (3 and 4), and transrepression-selective LXR ligands (5 and 6).

The transactivating activities of LXR ligands depend upon their effect on recruitment of cofactors (corepressors and coactivators), and currently known LXR ligands can be classified into two categories with respect to transactivation. Transactivating agonists activate expression of the target genes mentioned above. Numerous transactivating agonists for both LXRα/β, including T0901317 (3)6 and GW3965 (4),7 have been reported (Figure 1).8 Although LXRs appeared to be attractive molecular targets for medicaments, the major drawback of transactivating agonists is upregulation of multiple LXRE-containing target genes, including sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) and fatty acid synthase (FAS). Up-regulation of these genes, especially in liver, leads to increased triglyceride (TG) accumulation and induces serious hypertriglyceridemia.9 This side effect is a major barrier to medical application of LXR-transactivating agonists.

In contrast with transactivating agonists, transactivating antagonists stabilize the binding of corepressors and repress expression of the target genes. LXRs antagonists might have therapeutic value for hepatic steatosis.10 We11,12 and other groups10,13,14 have reported several chemical classes of LXR-transactivational antagonists.

Recent studies have revealed that LXRs also function in the regulation of inflammation in macrophages.15−17 In vitro, several LXR ligands inhibit the expression of proinflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), in response to bacterial infection or lipopolysaccaride (LPS) stimulation. The promoter regions of these proinflammatory genes do not contain LXRE, which is present in all genes showing LXR-dependent transactivation. This gene expression-inhibitory function of LXR, i.e., inhibition of LXRE-independent gene transcription by an LXR ligand, is called transrepression. In 2007, Ghisletti et al. proposed that 4 showed transrepressional activity through including SUMOylation of LXR and blocking of corepressor clearance.18 Studies in LXR-knockout mice indicated that transrepression is mediated by both LXRα and LXRβ. Transrepressional activities of LXR ligands were reported to improve skin inflammation,19 rheumatoid arthritis,20 sepsis,21 and hepatic injury caused by endotoxemia22 in animal models. Therefore, LXR ligands that show transrepression activity are promising candidates for treatment of these inflammatory diseases.

Selective LXR modulators that preferentially exhibit transrepression activity should exhibit anti-inflammatory properties with fewer side effects. Although LXR ligands such as 3 and 4 exhibit both transactivating and transrepressional activities, the first transrepression-selective LXR modulators were reported by GlaxoSmithKline in 2008.23 Compound 5 has similar transrepressional activity to 3 and does not increase TG accumulation. However, 5 showed transactivating-agonistic activity in a cell-based reporter assay. In 2012, we reported that 6 showed more potent transrepressional activity than 3 or 5 and lacked transactivating activity at 30 μM under our assay conditions.24 Very few transrepression-selective LXR modulators have yet been reported,23,24 and a recent Perspective noted that “SAR of transrepression is not well understood, and this remains an underexplored area with potential in several disease areas.”8 Therefore, investigation of the SAR of transrepression-selective LXR modulators having various scaffolds should improve our understanding of the molecular basis of LXR-mediated transrepression. In this Letter, we present styrylphenylphthalimides as a new chemical class of potent and transrepression-selective LXR modulators.

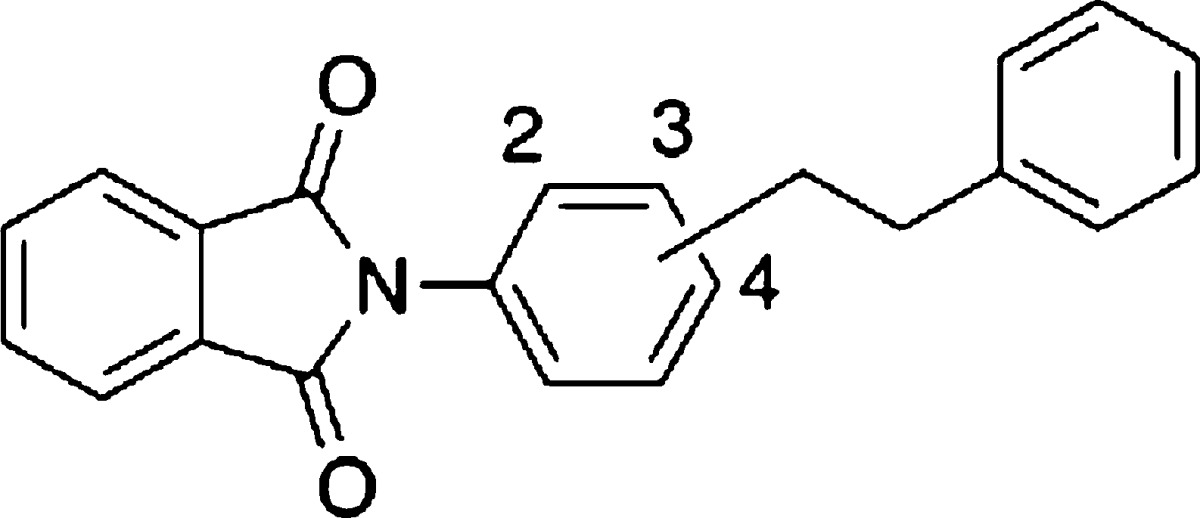

Styrylphenylphthalimide analogues were synthesized as described in the Supporting Information. To identify a lead compound, we focused on our LXR-transactivational antagonists since they might show transrepression in an LXR-dependent manner and do not show LXR-agonistic activity. Thus, we screened our antagonists and their analogues for transrepressional activity. Cell-based transrepressional activity was evaluated in terms of reduction of LPS-induced IL-6 expression (designated below as IL-6-inhibitory activity) in differentiated THP-1 (human acute monocytic leukemia) cells, which express both LXRα/β.25 LXR-transactivating agonistic activity and antagonistic activity were measured by means of the Gal4-human LXR reporter system. The screening identified ortho-phenethylphenylphthalimide (7),11 which showed a 31% reduction of IL-6 level at 10 μM (Table 1). This compound showed no LXRα/β-transactivating agonistic activity at 30 μM, but had weak LXRα/β-transactivational antagonistic activity.

Table 1. SAR of Substituted Position of Phenethylphenyl Group.

| LXRs

transactivation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LXRs transrepression | agonistic

activity EC50 (μM) |

antagonistic

activity IC50 (μM)c |

||||

| compd | position | % inhibition of IL-6 level at 10 μM | LXRα | LXRβ | LXRα | LXRβ |

| 7 | 2 | 31 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 13 | >30 (46%) |

| 8 | 3 | 9 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 11 | >30 (48%) |

| 9 | 4 | N.A.a | N.A.b | N.A.b | >30 (20%) | >30 (26%) |

No activity at 10 μM.

No activity at 30 μM.

Percent inhibition at 30 μM is given in parentheses.

The results of screening led us to select 7 as a novel lead compound, and we next synthesized various analogues to clarify the SAR. First, the substitution position of the central phenyl group was investigated. Meta (8) and para (9) analogues11 lacked IL-6-inhibitory activity (Table 1). This result led us to fix the site of phenethyl substitution as the ortho-position. None of the analogues in Table 1 showed LXRs-agonistic activity.

The ethylene linker moiety was next examined (Table 2). At the same time, a methoxy group was introduced at the para-position of the phenethylphenyl group because many types of LXR ligands possess a methoxy group(s).11,23,26,27 However, introduction of the methoxy group (20b) did not result in any increase of IL-6-inhibitory activity compared with 7. Replacement of the ethyl linker of methoxy analogue 20b with the ethylene linker (17b) improved IL-6-inhibitory activity. This result led us to fix the linker as an ethylene group.

Table 2. SAR of Substituent Effects of Styryl Group.

| LXRs

transactivation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LXRs transrepression | agonistic

activity EC50 (μM) |

antagonistic

activity IC50 (μM)d |

|||||

| compd | bonda | R | % inhibition of IL-6 level at 10 μM | LXRα | LXRβ | LXRα | LXRβ |

| 7 | s | H | 31 | N.A.c | N.A.c | 13 | >30 (46%) |

| 20b | s | MeO | 35 | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (30%) | N.A.c |

| 17a | d | H | 12 | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (40%) | >30 (38%) |

| 17b | d | MeO | 50 | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (30%) | >30 (21%) |

| 17c | d | F | N.A.b | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (48%) | >30 (37%) |

| 17d | d | Br | 14 | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (21%) | >30 (28%) |

| 17e | d | CN | 27 | N.A.c | N.A.c | 27 | >30 (35%) |

| 17f | d | Me | 16 | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (49%) | >30 (20%) |

| 17g | d | CF3 | 27 | N.A.c | N.A.c | 23 | >30 (17%) |

| 17h | d | n-Bu | 29 | N.A.c | N.A.c | >30 (38%) | >30 (15%) |

| 17i | d | t-Bu | 16 | N.A.c | N.A.c | 6.8 | 6.8 |

s, single bond; d, double bond.

No activity at 10 μM.

No activity at 30 μM.

Percent inhibition at 30 μM is given in parentheses.

We next explored the effect of the substituent on the terminal benzene ring of the styryl moiety (Table 2). We synthesized several analogues 17c–17i possessing various small (F, Me) or large (Br, n-Bu, t-Bu) monosubstituents and with electron-withdrawing (CN, F, Br, CF3) or electron-donating (Me, n-Bu, t-Bu) groups. However, all the analogues prepared showed weaker activity than 17b. This result indicates that the methoxy group is important for transrepression activity. The tertiary-Bu analogue 17i showed the strongest LXRs-antagonistic activity among the compounds listed in Table 2, but showed only weak IL-6-inhibitory activity. This result indicated that not all the LXRs antagonists are potent IL-6 inhibitors.

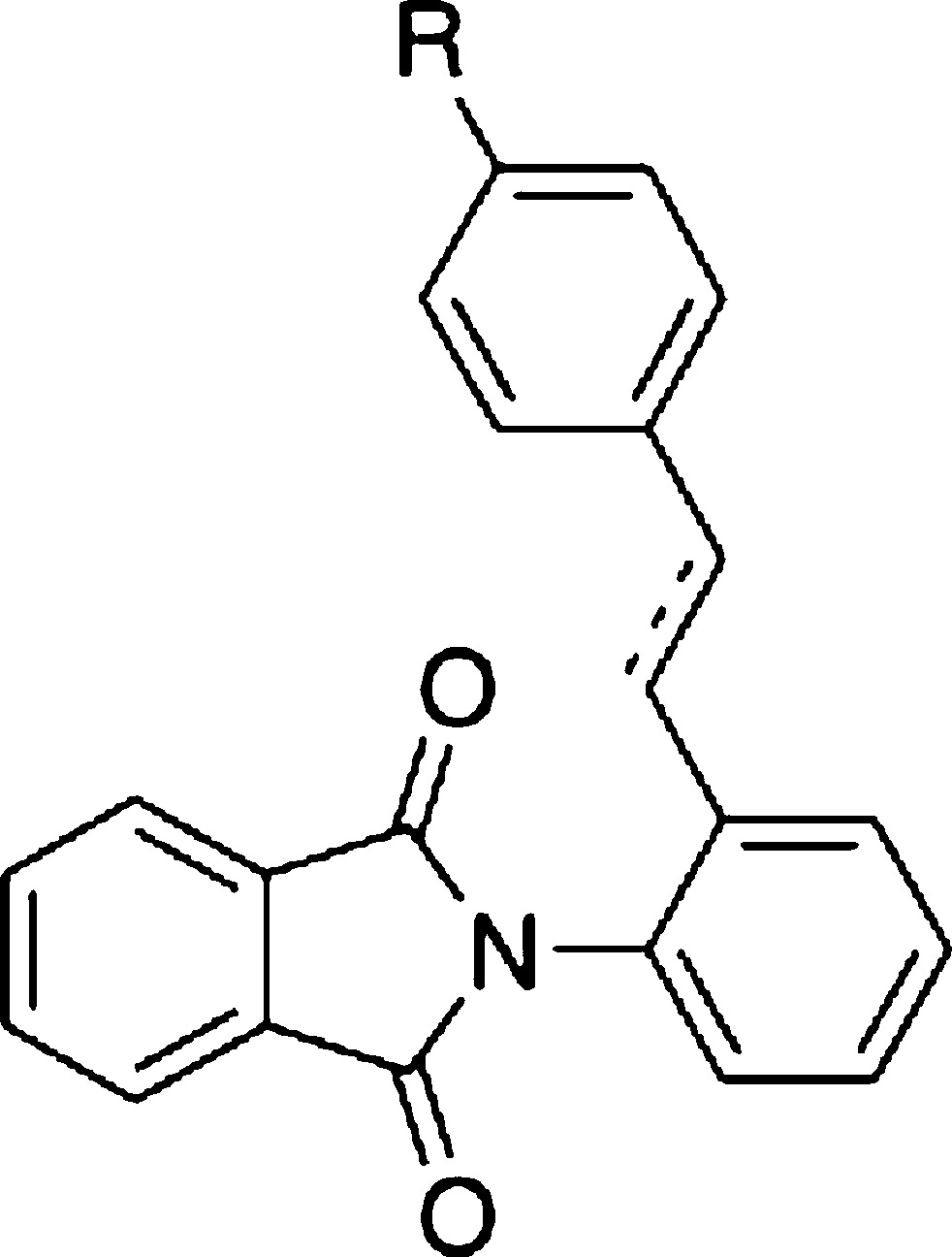

Next, we investigated the substitution pattern of methoxy group(s) (Table 3). Compared with the case of the mono-methoxy group, IL-6-inhibitory activity of the ortho-methoxy analogue 17j was weaker than those of the meta (17k) and para (17b) analogues. So, we focused on di/tri-methoxy analogues bearing methoxy groups at the meta- and/or para-positions. The 3,4-dimethoxy analogue 17l showed increased IL-6-inhibitory activity (78% inhibition at 10 μM). However, the IL-6-inhibitory activity was dramatically decreased in the cases of 3,5-dimethoxy analogue 17m and 3,4,5-trimethoxy analogue 17n. Next, we again tried to optimize the linker moiety. We found the E-isomer 17l was more potent than the corresponding Z-isomer 18l or the ethyl derivative 20l. Monomethyl isomers 17f,o,p and dimethyl isomers 17q–r were less potent than 17l. These results again show that methoxy group(s) are important for transrepression activity. As for substitution positions, 3,4-diMe analogue 17q showed more potent IL-6-inhibitory activity than 3,5-diMe analogue 17r, and this was consistent with the results for diMeO-substituted derivatives. Therefore, 3,4-disubstitution might match the binding pocket of LXR.

Table 3. SAR of Introduction of Methoxy and Methyl Group(s).

| LXRs

transactivation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LXRs transrepression | agonistic

activity EC50 (μM) |

antagonistic

activity IC50 (μM)c |

||||

| compd | R | % inhibition of IL-6 level at 10 μM | LXRα | LXRβ | LXRα | LXRβ |

| 17b | 4-MeO | 50 | N.A.b | N.A.b | >30 (30%) | >30 (21%) |

| 17j | 2-MeO | N.A.a | N.A.b | N.A.b | 30 | >30 (39%) |

| 17k | 3-MeO | 28 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 30 | >30 (17%) |

| 17l | 3,4-diMeO | 78 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 3.3 | 4.3 |

| 17m | 3,5-diMeO | N.A.a | N.A.b | N.A.b | 13 | 15 |

| 17n | 3,4,5-triMeO | 15 | N.A.b | N.A.b | >30 (44%) | >30 (38%) |

| 18l | 40 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 17 | 21 | |

| 20l | 13 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 23 | >30 (33%) | |

| 17f | 4-Me | 16 | N.A.b | N.A.b | >30 (49%) | >30 (20%) |

| 17o | 2-Me | N.A.a | N.A.b | N.A.b | 22 | 25 |

| 17p | 3-Me | 10 | N.A.b | N.A.b | 25 | >30 (20%) |

| 17q | 3,4-diMe | 32 | N.A.b | N.A.b | >30 (41%) | N.A.b |

| 17r | 3,5-diMe | N.A.a | N.A.b | N.A.b | >30 (43%) | >30 (30%) |

No activity at 10 μM.

No activity at 30 μM.

Percent inhibition at 30 μM is given in parentheses.

Compound 17l showed dose-dependent transrepressional activity. The IC50 value was estimated to be 1.5 μM, which was about 16-fold more potent than representative LXR agonist 3 and 1.1-fold more potent than our previous transrepression-selective LXR ligand 6 (Table 4). Furthermore, 17l was transrepression-selective, that is, it showed LXRα/β-antagonistic activity with IC50 values of 3.3 and 4.3 μM, respectively, and did not show LXRs-agonistic activity or LXRs-inverse agonistic activity at 30 μM.

Table 4. IC50 Values and EC50 Values of Representative Transrepression-Selective LXR Modulators.

| LXRs

transactivation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LXRs transrepression | agonistic

activity EC50 (μM) |

antagonistic

activity IC50 (μM) |

|||

| compound | inhibition of IL-6 level IC50 (μM) | LXRα | LXRβ | LXRα | LXRβ |

| 3 | 26 ± 17 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.066 ± 0.013 | N.T.b | N.T.b |

| 6 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | N.A.a | N.A.a | 4.1 ± 0.045c | 11 ± 0.43c |

| 17l | 1.5 ± 0.8 | N.A.a | N.A.a | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 4.3 ± 0.46 |

LPS transmits inflammatory signaling through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in the plasma membrane, and this induces degradation of the transrepressional complex on the promoter region of proinflammatory genes, thereby activating gene transcription.28 So, LPS-induced IL-6 expression is also reduced by TLR4 antagonists or TLR4-signaling inhibitors. To examine whether the decrease of IL-6 by 17l was LXR-dependent, we used the recently developed CRISPR/Cas (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR associated proteins) technology.29 LXRβ level in differentiated THP-1 cells was decreased by transfection of LXRβ CRISPR/Cas9 knockout plasmid (Figure S1a, Supporting Information). The IL-6 level was significantly reduced by 17l without transfection of LXRβ CRISPR/Cas9 knockout plasmid (Figure S1b). However, the decrease in IL-6 expression induced by 17l was blocked by transfection of LXRβ CRISPR/Cas9 knockout plasmid (Figure S1c). This result indicates that LXRβ contributes to the decrease of LPS-induced IL-6 expression by 17l, at least in part. On the other hand, ligands for other NRs such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are also known to show transrepression activity.18 Therefore, selectivity of 17l over PPARs was evaluated. Compound 17l did not show agonistic activities toward PPARα, PPARγ, or PPARδ, respectively (Figure S2, Supporting Information).

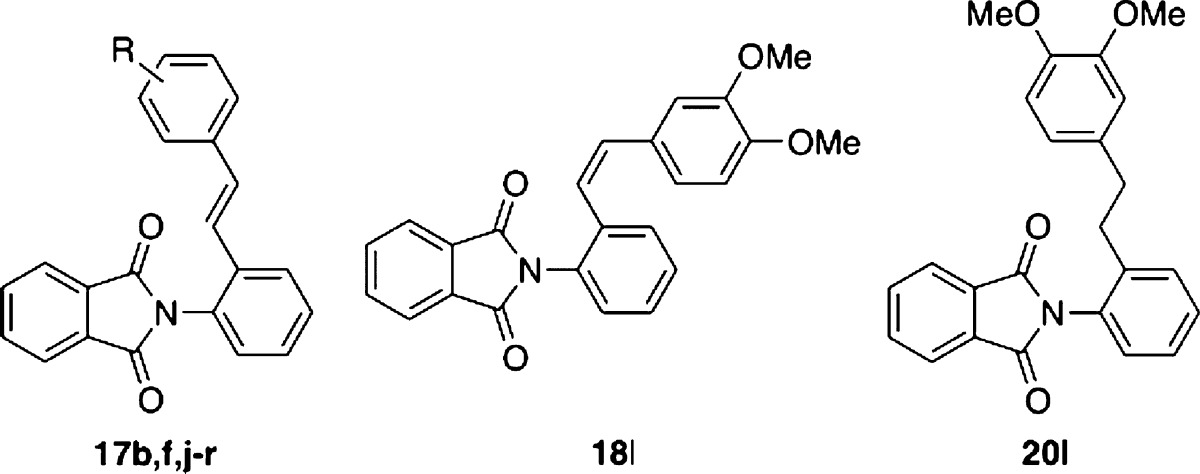

We next investigated whether 17l binds directly to LXR by means of time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) assay. In theory, the binding affinity between LXR and the coactivator peptide can be evaluated in terms of the TR-FRET ratio in the presence of agonist 3. In our experiment, the binding affinity was maximum when the concentration of 3 was higher than 0.1 μM. Inhibition of binding between LXR and the coactivator by 17l was assayed in terms of decrease of this FRET signal due to competition of 3 with 17l. Under the assay conditions used, compound 17l inhibited the FRET signal in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2). This result indicates that 17l binds directly to LXRβ LBD. IC50 value of 17l was estimated to 1.8 μM from Figure 2.

Figure 2.

LXR binding assay of 17l by means of TR-FRET.

Compounds 17l and 3 were expected to share the same binding site because 17l showed antagonistic activity toward agonist 3 in LXRs LBD reporter gene assay. To understand the binding mode between 17l and LXR, 17l was computationally docked into the cocrystal structure of LXRα LBD complexed with 4 (Figure S3a, Supporting Information).30 The most favored conformation had a free energy of binding of −11 kcal/mol, indicating that 17l binds at the binding site of LXRα (Figure S3b). The dimethoxyphenyl group on 17l faces toward H12 and occupies the pocket to which the chloro-trifluorophenyl group of 4 binds. The docking model predicts hydrogen-bonding interaction of the carbonyl group on 17l and the hydroxyl group on Thr302 of LXRα. According to the X-ray crystal structures of 3 and LXRs LBD,31,32 the hydroxyl group of 3 forms a hydrogen bond with a histidine residue (His421 for LXRα and His435 for LXRβ) in helix 11, adjacent to H12, and this histidine interacts with a tryptophan residue in H12; these interactions induce proper folding of H12, affording transcriptionally active LXRs. It is noteworthy that 17l did not appear to form a hydrogen bond with His421. This might be the reason why 17l showed selective transrepressional activity, versus transactivating activity.

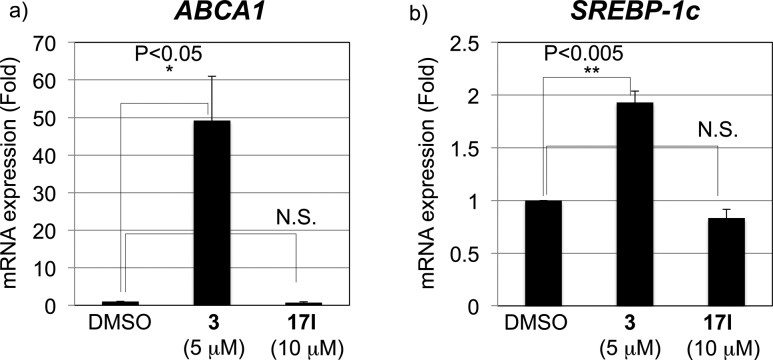

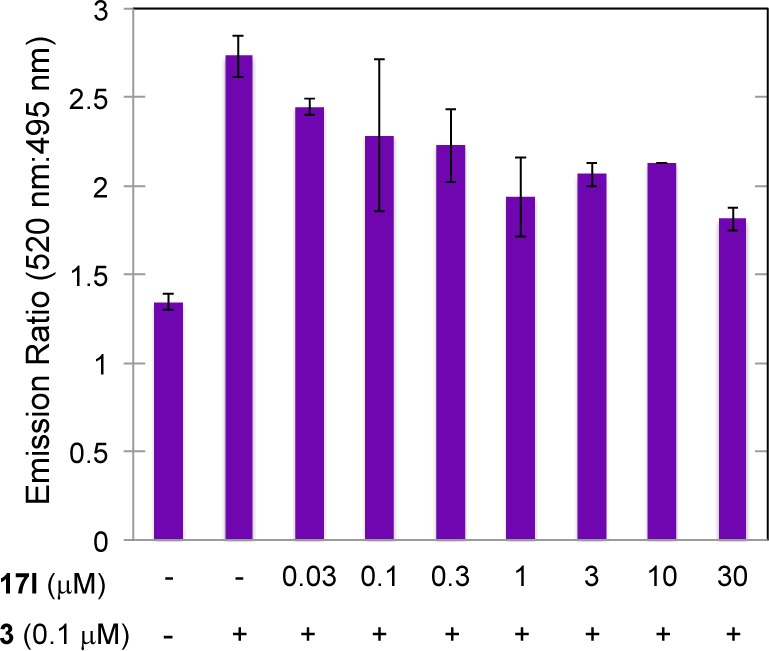

We next examined the selectivity of 17l by means of mRNA expression analysis of ABCA1 and SREBP-1c. In THP-1 cells, 17l did not upregulate ABCA1 and SREBP-1c mRNA expression, unlike 3 (Figure 3), indicating that it does not exhibit transactivating agonist activity. Therefore, 17l should not increase blood TG and may be a safer candidate as an anti-inflammatory medicine than LXR ligands possessing both transactivating-agonistic activity and transrepression activity.

Figure 3.

Effect of 17l on mRNA expression of (a) ABCA1 and (b) SREBP-1c in THP-1 cells.

In summary, we have identified novel LXR antagonists with a phenethylphenylphthalimide skeleton and investigated their SAR, focusing on IL-6-inhibitory activity and transactivational agonistic/antagonistic activities evaluated by means of LXR reporter gene assay. Representative compound 17l was found to show potent LXR transrepressional activity with high selectivity and did not increase expression of SREBP-1c (a side effect of LXR agonists) in cells. In addition, 17l was confirmed to have LXR-dependent transrepressional activity by using the CRISPR/Cas system and was shown to bind directly to LXRβ. This compound should be useful not only as a chemical tool for studying the biological functions of LXRs transrepression but also as a candidate for a safer agent to treat inflammatory diseases.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- Cas

CRISPR-associated protein

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- fas

fatty acid synthase

- H12

helix 12

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- LXR

liver X receptor

- LXRE

LXR response element

- NR

nuclear receptor

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c

- TG

triglyceride

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis, Figures S1–S3, experimental section, and purity of the synthesized compounds. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00170.

The work described in this Letter was partially supported by Grants-in Aid for Scientific Research from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics, and Structural Life Science.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Peet D. J.; Janowski B. A.; Mangelsdorf D. J. The LXRs: A New Class of Oxysterol Receptors. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1998, 8, 571–575. 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski B. A.; Willy P. J.; Devi T. R.; Falck J. R.; Mangelsdorf D. J. An Oxysterol Signalling Pathway Mediated by the Nuclear Receptor LXR Alpha. Nature 1996, 383, 728–731. 10.1038/383728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski B. A.; Grogan M. J.; Jones S. A.; Wisely G. B.; Kliewer S. A.; Corey E. J.; Mangelsdorf D. J. Structural Requirements of Ligands for the Oxysterol Liver X Receptors LXRα and LXRβ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 266–271. 10.1073/pnas.96.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Färnegårdh M.; Bonn T.; Sun S.; Ljunggren J.; Ahola H.; Wilhelmsson A.; Gustafsson J. Å.; Carlquist M. The Three-Dimensional Structure of the Liver X Receptor B Reveals a Flexible Ligand-Binding Pocket That Can Accommodate Fundamentally Different Ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 38821–38828. 10.1074/jbc.M304842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencikiene J.; Rydén M. Liver X Receptors and Fat Cell Metabolism. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 1494–1502. 10.1038/ijo.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Liu J.; Zhu L.; Cutler S.; Hasegawa H.; Shan B.; Medina J. C. Discovery and Optimization of a Novel Series of Liver X Receptor-Alpha Agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 1638–1642. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. L.; Binz J. G.; Plunket K. D.; Morgan D. G.; Beaudet E. J.; Whitney K. D.; Kliewer S. A.; Willson T. M.; Fivush A. M.; Watson M. A.; et al. Identification of a Nonsteroidal Liver X Receptor Agonist through Parallel Array Synthesis of Tertiary Amines. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 1963–1966. 10.1021/jm0255116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice C. M.; Noto P. B.; Fan K. Y.; Zhuang L.; Lala D. S.; Singh S. B. The Medicinal Chemistry of Liver X Receptor (LXR) Modulators. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 7182–7205. 10.1021/jm500442z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa J. J.; Liang G.; Ou J.; Bashmakov Y.; Lobaccaro J. M. A.; Shimomura I.; Shan B.; Brown M. S.; Goldstein J. L.; Mangelsdorf D. J. Regulation of Mouse Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-1c Gene (SREBP-1c) by Oxysterol Receptors, LXRα and LXRβ. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2819–2830. 10.1101/gad.844900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffett K.; Solt L. A.; El-gendy B. E.-D. M.; Kamenecka T. M.; Burris T. P. A Liver-Selective LXR Inverse Agonist That Suppresses Hepatic Steatosis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 559–567. 10.1021/cb300541g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoshima K.; Noguchi-Yachide T.; Sugita K.; Hashimoto Y.; Ishikawa M. Separation of α-Glucosidase-Inhibitory and Liver X Receptor-Antagonistic Activities of Phenethylphenyl Phthalimide Analogs and Generation of LXRα-Selective Antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5001–5014. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi-Yachide T.; Aoyama A.; Makishima M.; Miyachi H.; Hashimoto Y. Liver X Receptor Antagonists with a Phthalimide Skeleton Derived from Thalidomide-Related Glucosidase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 3957–3961. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuercher W. J.; Buckholz R. G.; Campobasso N.; Collins J. L.; Galardi C. M.; Gampe R. T.; Hyatt S. M.; Merrihew S. L.; Moore J. T.; Oplinger J. A.; et al. Discovery of Tertiary Sulfonamides as Potent Liver X Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3412–3416. 10.1021/jm901797p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X.; Kopecky D. J.; Fisher B.; Piper D. E.; Labelle M.; McKendry S.; Harrison M.; Jones S.; Jaen J.; Shiau A. K.; et al. Discovery and Optimization of a Series of Liver X Receptor Antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 5966–5970. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S. B.; Bradley M. N.; Castrillo A.; Bruhn K. W.; Mak P. A.; Pei L.; Hogenesch J.; O’connell R. M.; Cheng G.; Saez E.; et al. LXR-Dependent Gene Expression Is Important for Macrophage Survival and the Innate Immune Response. Cell 2004, 119, 299–309. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S. B.; Castrillo A.; Laffitte B. A.; Mangelsdorf D. J.; Tontonoz P. Reciprocal Regulation of Inflammation and Lipid Metabolism by Liver X Receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 213–219. 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C. K.; Saijo K. Nuclear Receptor Transrepression Pathways That Regulate Inflammation in Macrophages and T Cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 365–376. 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisletti S.; Huang W.; Ogawa S.; Pascual G.; Lin M.-E.; Willson T. M.; Rosenfeld M. G.; Glass C. K. Parallel SUMOylation-Dependent Pathways Mediate Gene- and Signal-Specific Transrepression by LXRs and PPARgamma. Mol. Cell 2007, 25, 57–70. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler A. J.; Sheu M. Y.; Schmuth M.; Kao J.; Fluhr J. W.; Rhein L.; Collins J. L.; Willson T. M.; Mangelsdorf D. J.; Elias P. M.; et al. Liver X Receptor Activators Display Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Irritant and Allergic Contact Dermatitis Models: Liver-X-Receptor-Specific Inhibition of Inflammation and Primary Cytokine Production. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003, 120, 246–255. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asquith D. L.; Miller A. M.; Hueber A. J.; McKinnon H. J.; Sattar N.; Graham G. J.; McInnes I. B. Liver X Receptor Agonism Promotes Articular Inflammation in Murine Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 2655–2665. 10.1002/art.24717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y.; Ryg U.; Dahle M. K.; Steffensen K. R.; Thiemermann C.; Chaudry I. H.; Reinholt F. P.; Collins J. L.; Nebb H. I.; Aasen A. O.; et al. Liver X Receptor Protects against Liver Injury in Sepsis Caused by Rodent Cecal Ligation and Puncture. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt). 2011, 12, 283–289. 10.1089/sur.2010.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y.; Dahle M. K.; Agren J.; Myhre A. E.; Reinholt F. P.; Foster S. J.; Collins J. L.; Thiemermann C.; Aasen A. O.; Wang J. E. Activation of the Liver X Receptor Protects against Hepatic Injury in Endotoxemia by Suppressing Kupffer Cell Activation. Shock 2006, 25, 141–146. 10.1097/01.shk.0000191377.78144.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao E. Y.; Caravella J. A.; Watson M. A.; Campobasso N.; Ghisletti S.; Billin A. N.; Galardi C.; Wang P.; Laffitte B. A.; Iannone M. A.; et al. Structure-Guided Design of N-Phenyl Tertiary Amines as Transrepression-Selective Liver X Receptor Modulators with Anti-Inflammatory Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 5758–5765. 10.1021/jm800612u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama A.; Endo-Umeda K.; Kishida K.; Ohgane K.; Noguchi-Yachide T.; Aoyama H.; Ishikawa M.; Miyachi H.; Makishima M.; Hashimoto Y. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Transrepression-Selective Liver X Receptor (LXR) Ligands with 5,11-Dihydro-5-Methyl-11-Methylene-6H-Dibenz[b,e]azepin-6-One Skeleton. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7360–7377. 10.1021/jm3002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney K. D.; Watson M. A.; Goodwin B.; Galardi C. M.; Maglich J. M.; Wilson J. G.; Willson T. M.; Collins J. L.; Kliewer S. A. Liver X Receptor (LXR) Regulation of the LXRα Gene in Human Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 43509–43515. 10.1074/jbc.M106155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaye M. C.; Krawiec J. A.; Campobasso N.; Smallwood A.; Qiu C.; Lu Q.; Kerrigan J. J.; Alvaro M. D. L. F.; Laffitte B.; Liu W.; et al. Discovery of Substituted Maleimides as Liver X Receptor Agonists and Determination of a Ligand-Bound Crystal Structure. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5419–5422. 10.1021/jm050532w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molteni V.; Li X.; Nabakka J.; Liang F.; Wityak J.; Koder A.; Vargas L.; Romeo R.; Mitro N.; Mak P. A.; et al. N-Acylthiadiazolines, a New Class of Liver X Receptor Agonists with Selectivity for LXRbeta. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4255–4259. 10.1021/jm070453f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T.; Akira S. TLR Signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 816–825. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P.; Yang L.; Esvelt K. M.; Aach J.; Guell M.; DiCarlo J. E.; Norville J. E.; Church G. M. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339, 823–826. 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradera X.; Vu D.; Nimz O.; Skene R.; Hosfield D.; Wynands R.; Cooke A. J.; Haunsø A.; King A.; Bennett D. J.; et al. X-Ray Structures of the LXRα LBD in Its Homodimeric Form and Implications for Heterodimer Signaling. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 399, 120–132. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson S.; Östberg T.; Jacobsson M.; Norström C.; Stefansson K.; Hallén D.; Johansson I. C.; Zachrisson K.; Ogg D.; Jendeberg L. Crystal Structure of the Heterodimeric Complex of LXRα and RXRβ Ligand-Binding Domains in a Fully Agonistic Conformation. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 4625–4633. 10.1093/emboj/cdg456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.; Bledsoe R. K.; Collins J. L.; Boggs S.; Lambert M. H.; Miller A. B.; Moore J.; McKee D. D.; Moore L.; Nichols J.; et al. X-Ray Crystal Structure of the Liver X Receptor Beta Ligand Binding Domain: Regulation by a Histidine-Tryptophan Switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27138–27143. 10.1074/jbc.M302260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.