Abstract

The in vitro activity of the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] was inhibited by CuCl2 with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 2.8 μM. The growth of an amikacin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strain isolated from a neonate with meningitis was inhibited when amikacin was supplemented by the addition of Zn2+ or Cu2+ in complex with the ionophore pyrithione. Coordination complexes between cations and ionophores could be developed for their use, in combination with aminoglycosides, to treat resistant infections.

TEXT

Klebsiella pneumoniae is part of the ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) group of bacteria, which are responsible for the majority of U.S. hospital infections and received the name because they “escape” the effects of antibacterial drugs (1). The most common infections caused by K. pneumoniae are pneumonia, septicemias, urinary tract infections, meningitis, and soft tissue infections (2–4). Less common infections caused by this bacterium are septic arthritis (5), liver abscess and invasive syndrome (6), and generalized pustulosis (7). In addition, recent reports propose K. pneumoniae as a triggering factor for ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn's disease (8).

Amikacin (AMK), alone or in combination, is an antibiotic of choice to treat certain K. pneumoniae infections: in particular, it is widely used in neonatal infections (4, 9, 10). However, in some parts of the world, AMK-resistant K. pneumoniae strains are becoming more common (11, 12). Resistance to AMK in K. pneumoniae is mostly caused by the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] enzyme, which is usually plasmid mediated (13, 14). K. pneumoniae JHCK1, a strain isolated from a neonate with meningitis, harbors 17 copies per cell of the plasmid pJHCMW1, which includes the aac(6′)-Ib gene (3, 15, 16). It is an adequate model to study K. pneumoniae virulence and resistance because its complete nucleotide sequence is known, and the resistance plasmid is one of the best characterized (15–17).

Recent efforts to isolate inhibitors of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and in particular AAC(6′)-Ib led to the description of small molecules and metal ions complexed to ionophores, such as zinc pyrithione (ZnPT), that can reverse growth of AMK-resistant bacteria in the presence of the antibiotic (18–24). In this work, we show that Zn2+ and Cu2+ in complex with pyrithione induce a reduction in the AMK resistance levels of K. pneumoniae JHCK1.

K. pneumoniae JHCK1 (17) growth inhibition assays were carried out in Mueller-Hinton broth as described before (19). Zinc and copper pyrithione (ZnPT and CuPT, respectively) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and AK Scientific, Inc. (Union City, CA), respectively. Purification of AAC(6′)-Ib for in vitro enzymatic assays was carried out after overexpression using E. coli XL10-Gold harboring a plasmid, pBADMW131, in which the aac(6′)-Ib gene was placed under the control of the BAD promoter. Purification was done as described before (19) with the addition of a size exclusion fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) step with a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column under the conditions recommended by the supplier with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 100 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. Acetyltransferase activity was determined by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 412 nm when Ellman's reagent, 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) reacts with the coenzyme A (CoA)-SH released from acetyl-CoA after acetylation of the substrate (23).

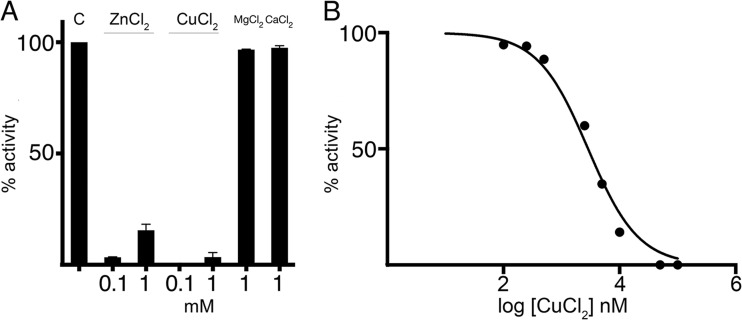

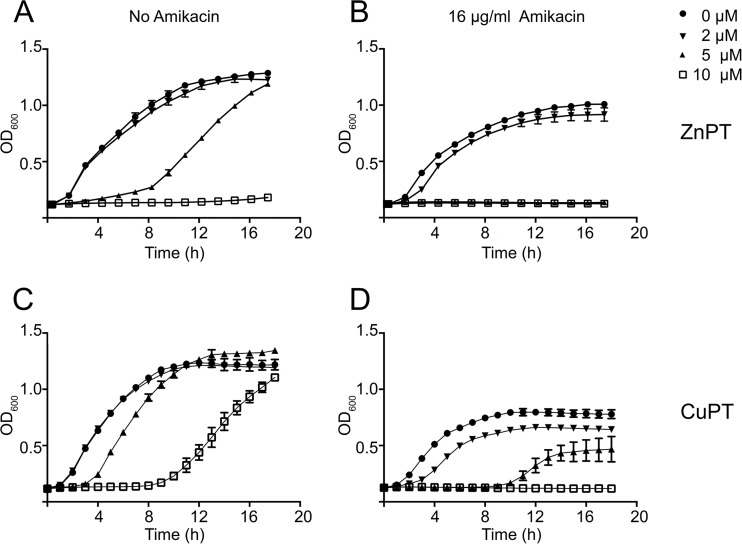

We recently showed that Zn2+ significantly interferes with the acetylation of aminoglycosides catalyzed by AAC(6′)-Ib (19). Assessment of other divalent cations showed that Cu2+ is also a robust inhibitor of the acetylation reaction with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 2 μM (Fig. 1A and B). This result agrees with that recently observed in a similar study (22). We showed before that the chloride salt of Zn2+ in combination with AMK induced inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli and Acinetobacter baumannii strains harboring aac(6′)-Ib; however, very high concentrations were required (19). Instead, when in complex with the ionophore pyrithione, the concentrations needed to inhibit growth were about 1,000-fold lower. The enhancement of the inhibitory effect was attributed to the known stimulation of internalization of Zn2+ by the ionophore (19, 25). On the basis of these results, we tested the effect of ZnPT or CuPT on the resistance to AMK of K. pneumoniae JHCK1. Figure 2A and B show that addition of 5 μM ZnPT to cultures containing 16 μg/ml AMK resulted in full growth inhibition. It can also be observed that ZnPT at this concentration produced an extension of the lag phase in the growth curve. However, the doubling time and maximum optical density at 600 nm (OD600) were unchanged with respect to cells growing in plain broth. This effect of pyrithione on K. pneumoniae cells has been observed before: a concentration-dependent lag phase was followed by normal growth, and the cells became resistant to the levels of pyrithione used during the first culture (26). However, the tolerance was lost after successive cultures in the absence of pyrithione (26). Interestingly, CuPT showed lower levels of toxicity: at 10 μM, the lag had a similar duration to that observed at 5 μM ZnPT (compare Fig. 2A and C). Figure 2D shows that CuPT inhibited the resistance to AMK, but the level of inhibition was not as high as that observed when ZnPT was tested. This was an interesting observation since Cu2+ was a more effective inhibitor of the acetylation reaction than Zn2+ in vitro. We do not know if the observed correlation between toxicity of the pyrithione complex and strength of inhibition of AMK resistance is a general property of metal-ionophore complexes. The mechanism of cation inhibition of enzymatic acetylation of aminoglycosides will be the subject of future studies. Inhibition could occur through binding to the enzyme in a competitive, noncompetitive, or uncompetitive manner, or it could occur through titration of the substrate aminoglycoside by formation of coordination complexes, a process that has been described for several metal ions, including Cu2+ and Zn2+ (27). Future studies will also test the action of ZnPT and CuPT on the proteins coded for by numerous existing alleles of aac(6′)-Ib (14). While many of the proteins differ at the N terminus and have similar characteristics, others show variations as small as one or two amino acids at key positions that have profound effects on the substrate profiles of the enzymes (14).

FIG 1.

Effect of copper on acetylation of AMK catalyzed by AAC(6′)-Ib. (A) Acetylating activity of AAC(6′)-Ib in the presence of different cations. Compounds were added at the indicated concentrations, and the activity was compared to that observed in the absence of additions (bar C). MgCl2 and CaCl2 were known not to inhibit the reaction and were tested as controls. (B) The percentage of acetylating activity of AMK by AAC(6′)-Ib was calculated for reaction mixtures containing different concentrations of CuCl2.

FIG 2.

Comparison of the effects of ZnPT and CuPT on resistance to AMK. K. pneumoniae JHCK1 cells were cultured in 100 μl Mueller-Hinton broth in microtiter plates at 37°C with the additions indicated in the figure, and the OD600 was periodically determined. The panels show the effect on cell growth of addition of ZnPT (A and B) or CuPT (C and D) in the presence (B and D) or absence (A and C) of 16 μg/ml AMK.

We conclude that coordination complexes between Cu2+ or Zn2+ and ionophores could be developed to act as adjuvants in combination with AMK or other aminoglycosides to treat infections caused by resistant pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ali Saleh for technical advice while carrying out FPLC chromatography.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant 2R15AI047115-04 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, to M.E.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK Jr, Bradley J, Guidos RJ, Jones RN, Murray BE, Bonomo RA, Gilbert D, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013. 10 x '20 Progress—development of new drugs active against Gram-negative bacilli: an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 56:1685–1694. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coque TM, Oliver A, Perez-Diaz JC, Baquero F, Canton R. 2002. Genes encoding TEM-4, SHV-2, and CTX-M-10 extended-spectrum beta-lactamases are carried by multiple Klebsiella pneumoniae clones in a single hospital (Madrid, 1989 to 2000). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:500–510. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.500-510.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. 1987. Tn1331, a novel multiresistance transposon encoding resistance to amikacin and ampicillin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 31:1955–1960. doi: 10.1128/AAC.31.12.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woloj M, Tolmasky ME, Roberts MC, Crosa JH. 1986. Plasmid-encoded amikacin resistance in multiresistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from neonates with meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 29:315–319. doi: 10.1128/AAC.29.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki K, Nakamura A, Enokiya T, Iwashita Y, Tomatsu E, Muraki Y, Kaneko T, Okuda M, Katayama N, Imai H. 2013. Septic arthritis subsequent to urosepsis caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae. Intern Med 52:1641–1645. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. 2012. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 12:881–887. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang HY, Wu YH, Kuo CF. 2013. Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis with unusual cutaneous presentation of generalized pustulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol 38:626–629. doi: 10.1111/ced.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashid T, Wilson C, Ebringer A. 2013. The link between ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease, Klebsiella, and starch consumption. Clin Dev Immunol 2013:872632. doi: 10.1155/2013/872632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labaune JM, Bleyzac N, Maire P, Jelliffe RW, Boutroy MJ, Aulagner G, Putet G. 2001. Once-a-day individualized amikacin dosing for suspected infection at birth based on population pharmacokinetic models. Biol Neonate 80:142–147. doi: 10.1159/000047133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch EB, Tam VH. 2010. Detection and treatment options for Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs): an emerging cause of multidrug-resistant infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1119–1125. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez GV, Master RN, Clark RB, Fyyaz M, Duvvuri P, Ekta G, Bordon J. 2013. Klebsiella pneumoniae antimicrobial drug resistance, United States, 1998-2010. Emerg Infect Dis 19:133–136. doi: 10.3201/eid1901.120310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saleem AF, Qamar FN, Shahzad H, Qadir M, Zaidi AK. 2013. Trends in antibiotic susceptibility and incidence of late-onset Klebsiella pneumoniae neonatal sepsis over a six-year period in a neonatal intensive care unit in Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis 17:e961–e965. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez MS, Traglia GM, Lin DL, Tran T, Tolmasky ME. 2014. Plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance and virulence in Gram-negatives: the Klebsiella pneumoniae paradigm. Microbiol Spectr 2:1–15. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0016-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez MS, Nikolaidis N, Tolmasky ME. 2013. Rise and dissemination of aminoglycoside resistance: the aac(6′)-Ib paradigm. Front Microbiol 4:121. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reyes-Lamothe R, Tran T, Meas D, Lee L, Li AM, Sherratt DJ, Tolmasky ME. 2014. High-copy bacterial plasmids diffuse in the nucleoid-free space, replicate stochastically and are randomly partitioned at cell division. Nucleic Acids Res 42:1042–1051. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarno R, McGillivary G, Sherratt DJ, Actis LA, Tolmasky ME. 2002. Complete nucleotide sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae multiresistance plasmid pJHCMW1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3422–3427. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3422-3427.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie G, Ramirez MS, Marshall SH, Hujer KM, Lo CC, Johnson S, Li PE, Davenport K, Endimiani A, Bonomo RA, Tolmasky ME, Chain PS. 2013. Genome sequences of two Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from different geographical regions, Argentina (strain JHCK1) and the United States (strain VA360). Genome Announc 1(2):e00168-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00168-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labby KJ, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2013. Strategies to overcome the action of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes for treating resistant bacterial infections. Future Med Chem 5:1285–1309. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin DL, Tran T, Alam JY, Herron SR, Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. 2014. Inhibition of aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib by zinc: reversal of amikacin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli by a zinc ionophore. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4238–4241. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00129-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin L, Tran T, Adams C, Alam JY, Herron SR, Tolmasky ME. 2013. Inhibitors of the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] identified by in-silico molecular docking. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23:5694–5698. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. 2010. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat 13:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Green KD, Johnson BR, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2015. Inhibition of aminoglycoside acetyltransferase resistance enzymes by metal salts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4148–4156. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00885-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green KD, Chen W, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2012. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of the aminoglycoside resistance acetyltransferase E is from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ChemMedChem 7:73–77. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lombes T, Begis G, Maurice F, Turcaud S, Lecourt T, Dardel F, Micouin L. 2008. NMR-guided fragment-based approach for the design of AAC(6′)-Ib ligands. Chembiochem 9:1368–1371. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.te Velthuis AJ, van den Worm SH, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. 2010. Zn(2+) inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001176. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khattar M. 1991. Growth and survival of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the presence of pyrithione. Ph.D. thesis University of Technology, Loughborough University, Loughborough, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlowski H, Kowalik-Jankowska T, Jezowska-Bojczuk M. 2005. Chemical and biological aspects of Cu2+ interactions with peptides and aminoglycosides. Coord Chem Rev 249:2323–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]