A decade ago, the first experimental validations of metabolite-binding riboswitches were being reported1-4. In these early papers, it was either implied or openly proposed that riboswitch-like molecules likely were present in early forms of life. These primeval “RNA World” riboswitches would have served both as chemical sensors and as regulatory elements long before proteins had emerged through evolution. If many riboswitches indeed are descendent from RNA-based life forms, then two new publications by the laboratories of Serganov5 and Batey6 provide us with spectacular views of a deluxe genetic device from the RNA World that still thrives in modern bacteria. Together these studies reveal amazing details on how a ubiquitous riboswitch class selectively grips a large and ancient coenzyme. Also amongst these new results is the discovery that some variants of this riboswitch class have evolved to detect a different metabolite target.

More than two dozen riboswitch types are now known7, but the class whose members sense and respond to derivatives of cobalamin (Cbl or vitamin B12) is special for several reasons. When first validated as riboswitches1, representative “B12 box” RNAs from Escherichia coli and from Salmonella typhimurim were shown to bind preferentially to the vitamin B12 derivative called adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl). Without the aid of proteins, these RNAs bind AdoCbl very precisely and very tightly, which are the hallmarks of most other riboswitch classes subsequently discovered.

Soon thereafter, an intriguing collection Cbl riboswitch variants were discovered in some organisms8, suggesting that these representatives either use an alternative RNA aptamer structure to bind a portion of AdoCbl or they have adapted to respond to a different Cbl derivative. Regardless, members of this Cbl riboswitch superfamily now appear to be more common than those of any other riboswitch class. This widespread distribution is consistent with the fact that Cbl-derived coenzymes are of ancient origin, ever-present, and critical for most species.

The smallest riboswitch aptamer (for the modified nucleobase called preQ1) can be formed from less than 35 nucleotides9, while the aptamer domains of most riboswitch classes are typically less than 100 nucleotides. In stark contrast, most Cbl riboswitch aptamers are formed from 200 nucleotides or more. Cbl riboswitch aptamers are big, and if sheer size was not sufficient to deter RNA structural biologists from pursuing x-ray structures of Cbl riboswitches, the extreme instability of AdoCbl under ambient light conditions seemed certain to confound even the boldest researchers for decades. However, the size and complexity of Cbl riboswitches also meant that they were sure to hold some surprises regarding riboswitch structure and function. Through a combination of skill and persistence, the Serganov5 and Batey6 labs have forced these RNAs to give up their structural secrets at atomic resolution, and they uncovered some very intriguing details. Although AdoCbl is the largest metabolite known to be recognized by a riboswitch, it still tiny compared to the size of the RNA that binds it. So, what is all this ancient RNA sequence and structure doing?

Not surprisingly, some of the most conserved segments of the aptamers form a binding pocket for the coenzyme. However, ligand recognition is achieved almost exclusively by van der Waals interactions between the nucleotides forming the pocket and the various moieties appended to the corrin ring. Since this riboswitch class is so common and controls genes whose protein products make available such a critical coenzyme, one would think that more specific bonding would be used to reduce the chances that the riboswitch would misfire by binding to the wrong metabolite. Perhaps some organisms indeed have evolved to produce natural products that trick Cbl riboswitches, but none have been discovered so far. Also, there is only one superfamily of Cbl riboswitches known, and so this single major solution to the problem of sensing Cbl is quite successful. Therefore, the findings to date suggest that this mostly “hand-in-glove” binding strategy used by Cbl riboswitches is more than adequate to survive through eons of evolution.

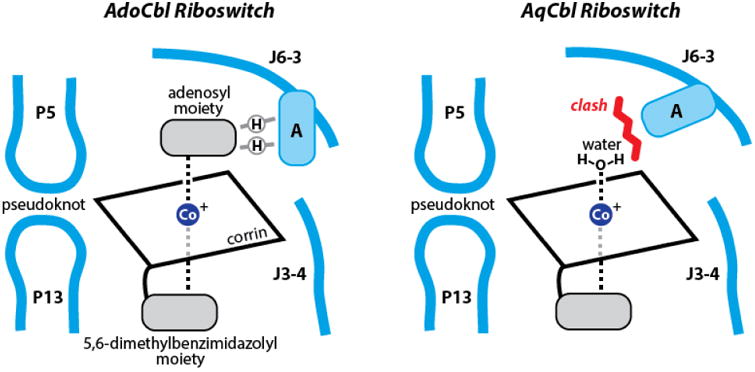

Structures of the more common Cbl riboswitch type reveals that they form two hydrogen bonds between the adenosyl moiety of AdoCbl and an adenosine of the aptamer J6-3 region (Fig. 1, left). These interactions rely on the precise conformation of J6-3, which is assisted by the extensive substructures carried by this aptamer type. These interactions establish ligand specificity for AdoCbl, and therefore representatives of this type are called AdoCbl riboswitches.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the riboswitch binding sites for AdoCbl (left) and AqCbl (right). Light blue lines represent riboswitch substructures as indicated, where A designates an adenosine nucleotide within J6-3 that directly influences ligand specificity. Encircled H denotes a hydrogen bond. The red line indicates a clash between the adenosine nucleotide and any bulky ligand on Cbl.

Importantly, both biochemical and genetic evidence is presented that reveals the variant riboswitch type favors binding aquocobalamin (AqCbl), wherein the adenosyl moiety of the coenzyme is replaced by water. Batey and colleagues reason that certain organisms exposed to high light intensities, such as ocean-going bacteria, have an advantage by sensing the more stable AqCbl derivative. Thus, they have evolved a variant AqCbl-specific riboswitch type. Although the J6-3 sequence remains carries the same consensus sequence in both riboswitch types, AqCbl riboswitches carry distinct accessory sub-structures that alter the conformation of the adenosine moiety in this region that otherwise forms hydrogen bonds to AdoCbl. A shift in the location of this nucleotide causes a steric clash with Cbl derivatives that carry large substituents (Fig. 1, right), and therefore AqCbl is selectively bound by these variants.

With these structures in hand, those interested in developing riboswitch-targeting antibiotics have a form of heads-up display to aid them in designing novel ligands. Also, these structures make in even more enjoyable to speculate about what B12-utilizing ribozymes from the RNA World might have looked like. As noted above, the binding-pocket structures of AdoCbl and AqCbl riboswitches differ in the J6-3 region, which sits astride the hemisphere of coenzyme B12 that is reactive part of the molecule. Thus, in a hypothetical ribozyme ancestor, substrates for methylation, reduction, or various rearrangement reactions promoted by the coenzyme10 would need to approach the corrin ring through the space currently occupied by J6-3. Interestingly, it is this precise region that can adopt different conformations when selectively binding AdoCbl or AqCbl.

Moreover, the large accessory sub-structures in certain AdoCbl variants are in the vicinity of J6-3, demonstrating that a great diversity of RNA sequences and shapes could be accommodated near the reactive face of the coenzyme. Could it be that ancient ribozymes utilized coenzyme B12 by forming a binding pocket much like this modern riboswitch? Such ribozymes might even have catalyzed the reduction reaction necessary to convert RNA nucleotides into their DNA counterparts by holding substrates near where J6-3 is today. Other ribozymes based on this coenzyme-binding core might have been formed by swapping out these accessory sub-structures with others to selectively catalyze coenzyme B12-dependent reactions on other substrates.

It seems likely that all such speculative ribozymes have long since become extinct. Perhaps, however, we should keep a lookout for additional strange Cbl riboswitch variants with novel architectures near the J6-3 region. These RNAs might function as riboswitches with distinctive ligand recognition capabilities, or perhaps they represent modern examples of coenzyme B12-dependent ribozymes.

Acknowledgments

RNA research in the author's laboratory is supported by the NIH and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The author is a cofounder of BioRelix which has licensed riboswitch intellectual property from Yale University.

References

- 1.Nahvi A, et al. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. Nature. 2002;419:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mironov AS, et al. Cell. 2002;111:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15908–15913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212628899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peselis A, Serganov A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1182–1184. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson JE, Jr, Reyes FE, Polaski JT, Batey RT. Nature. 2012;492:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nature11607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breaker RR. Mol Cell. 2011;43:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahvi A, Barrick JE, Breaker RR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:143–150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth A, et al. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golding BT, Buckel W. Comprehensive Biological Catalysis. III. Academic Press Ltd.; pp. 239–259. [Google Scholar]