Significance

An unresolved question in ecology is whether the structure of ecological communities can be stable over very long timescales. Here we describe a wealth of new amber fossils for an ancient radiation of Hispaniolan lizards that, until now, has had a very poor fossil record. These fossils provide an important and previously unavailable perspective on an ecologically well-studied group and indicate that anole lizard communities occurring on Hispaniola 20 Mya were made up of the same types of habitat specialists present in this group today. These data indicate that the ecological processes important in extant anole communities have been operative over long periods of time.

Keywords: adaptive radiation, ecomorph, Hispaniola, Miocene, Anolis

Abstract

Whether the structure of ecological communities can exhibit stability over macroevolutionary timescales has long been debated. The similarity of independently evolved Anolis lizard communities on environmentally similar Greater Antillean islands supports the notion that community evolution is deterministic. However, a dearth of Caribbean Anolis fossils—only three have been described to date—has precluded direct investigation of the stability of anole communities through time. Here we report on an additional 17 fossil anoles in Dominican amber dating to 15–20 My before the present. Using data collected primarily by X-ray microcomputed tomography (X-ray micro-CT), we demonstrate that the main elements of Hispaniolan anole ecomorphological diversity were in place in the Miocene. Phylogenetic analysis yields results consistent with the hypothesis that the ecomorphs that evolved in the Miocene are members of the same ecomorph clades extant today. The primary axes of ecomorphological diversity in the Hispaniolan anole fauna appear to have changed little between the Miocene and the present, providing evidence for the stability of ecological communities over macroevolutionary timescales.

Ecologists and evolutionary biologists have long debated the temporal stability of community structure. In recent years, many comparisons of glacial and postglacial communities have shown great dissimilarities—species have responded to environmental change individualistically, indicating that the structure and function of assemblages can change substantially over even short geological timescales (e.g., several thousand to a few million years) (1–3). Conversely, some researchers have argued for stability in community structure (4), leading to communities that may be composed of stable sets of ecological specialists for millions of years (5, 6).

Caribbean Anolis lizards are a contemporary model of similarity in community structure. Replicated adaptive radiations have occurred independently on each island in the Greater Antilles, producing a similar set of habitat specialists, termed ecomorphs, on each island (7, 8). This similarity in community structure across islands suggests that anole communities are more than ephemeral and haphazard sets of species that happen to occupy the same place at the same time (9). However, in the absence of a substantial fossil record, it has not previously been possible to directly assess whether similarly structured communities are a recent phenomenon or whether ecological stability has been a longstanding characteristic of these island anole faunas.

Here we report on 20 remarkable Anolis fossils in amber from the island of Hispaniola. Using 3D reconstructions based on X-ray microcomputed tomography (X-ray micro-CT) and detailed morphometric analysis of these fossils, we show that the main elements of Hispaniolan anole ecomorphological diversity were in place in the Miocene, confirming the antiquity of the island radiation. This continuity emphasizes the stability of ecology specialization subsequent to initial adaptive diversification.

Amber, which is fossilized tree resin, provides a unique opportunity to examine ancient ecosystems by offering unparalleled preservation of biological material. In the Greater Antilles, amber has been found on a few islands in small quantities, but amber from the Dominican Republic stands out due to its quantity and quality of fossil inclusions (10–12). To date, amber fossils have been recovered for a variety of vertebrate groups (13–16), but most are presently known from only one or a few specimens, which limits the potential for drawing general conclusions about the evolution of these groups.

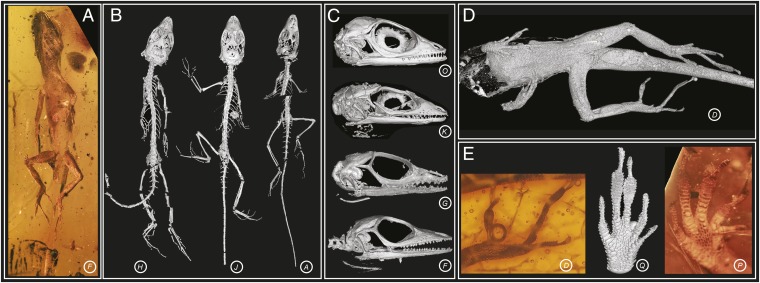

The pre-Pleistocene fossil record for anoles consists solely of amber fossils (15, 17–19). Previous authors have reported three anole fossils from Dominican amber, all dated within the Miocene, 15–20 Mya (20) and potentially members of the same species (15, 18, 19). We vastly expanded this sample by examining an additional 35 fossils (as well as reexamining the original 3), including all but one specimen known to us. Of these, we present data on 20 fossils that preserve substantial skeletal material or soft tissue to provide information on ecomorphological variation (Table S1). The fossils vary in state of preservation and completeness of the skeleton, from full skeletons to isolated limbs and heads (Fig. 1 A–D and Movie S1). Extraordinary detail of the squamation is preserved in many fossils (Fig. 1D), revealing the subdigital lamellae (transversely widened scales comprising the toepad), a character that informs on the arboreal behavior of these lizards (21) (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1).

Table S1.

The 20 fossils examined in this study

| Specimen | Specimen ID | Elements preserved | Specimen location | Notes on specimen | Locality of origin | Scanned where and by whom | kV | µA | Voxel size (mm) | Rotation step (o) | Exposure (ms) |

| A | AMNH DR SH 1 | Whole body | American Museum of Natural History, New York | Curator David Grimaldi | Dominican Republic | Harvard Centre for Nanoscale Systems Material Synthesis Facility (CNS); Emma Sherratt (ES) & Jasmine Casart | 70 | 120 | 0.0267 | 0.11 | 1,000 |

| B | I | Whole body | Private collection | Owned by Marilyn Halonen and Michael Cusanovich of Tuscon, Arizona | Dominican Republic | CNS; D. Luke Mahler | 55 | 185 | 0.0452 | 0.25 | — |

| C | II | Whole body | Private collection | Owned by Jim Work of Central Point, Oregon | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 65 | 195 | 0.0609 | 0.11 | 1,000 |

| D | III | Whole body | Private collection | Jose Calbeto of Guaynabo, Puerto Rico | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 55 | 165 | 0.0149 | 0.11 | 1,415 |

| E | M-1062 | Part (hindlimbs and tail) | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | Imaging and Analysis Centre, Natural History Museum London (IAC-NHM); ES & Russell Garwood (RG) | 105 | 195 | 0.0107 | 0.06 | 354 |

| F | M-1153 | Whole body | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | IAC-NHM; ES & RG | 105 | 195 | 0.0135 | 0.06 | 354 |

| G | M-3410 | Whole body | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | IAC-NHM; ES & RG | 105 | 195 | 0.0330 | 0.06 | 354 |

| H | M-525 | Whole body | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | IAC-NHM; ES & RG | 105 | 195 | 0.0210 | 0.06 | 500 |

| I | NMBA Entom P52 | Whole body | Naturhistorisches Museum, Basal Switzerland | Obtained by C. Baroni-Urbani, NMBA, Basel | La Toca mine, Cordillera Septentrional, Dominican Republic | Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, Renaud Boistel & Anthony Herrel | — | — | 0.00746 | — | — |

| J | OAAAA | Whole body | Private collection | Supplied by Marco Greco (Ambras Greco SAS) of Milan, Italy | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 75 | 130 | 0.0237 | 0.11 | 1,000 |

| K | SMNS Do-4871-M | Part (head) | Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany | Donated by Georg Dommel of Düsseldorf, Germany in 1985 | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 50 | 140 | 0.0077 | 0.11 | 1,415 |

| L | SMNS Do-4886-B | Part (tail, hindlimb) | Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany | Purchased in 1985 from Erich Beyna, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 50 | 180 | 0.0124 | 0.11 | 1,000 |

| M | SMNS Do-5566-X | Part (trunk, forelimb, hindlimbs) | Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany | Purchased 1991 from D. M. Salem, 8950 Sunrise Lake Blvd. 80/311, Sunrise, FL 33322, USA | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 50 | 130 | 0.0256 | 0.11 | 1,415 |

| N | SMU 74976 | Part (head) | Shuler Museum of Paleontology, South Methodist University, Dallas TX | Donated by William S. Lowe of Granbury Texas | Dominican Republic | University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility, Rich Ketcham | 80 | 200 | 0.0680 | 0.13 | — |

| O | USNM 580060 | Part (head, forelimb) | Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, Washinton DC | Purchased from Amberica West | La Toca mine, Cordillera Septentrional, Dominican Republic | University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility, Matthew Colbert | 180 | 133 | 0.0127 | 0.23 | — |

| “ | “ | “ | “ | “ | “ | CNS; ES | 60 | 165 | 0.0051 | 0.18 | 1,000 |

| P | M-2096 | Part (trunk and forelimbs) | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | IAC-NHM; ES & RG | 105 | 195 | 0.0168 | 0.06 | 354 |

| Q | RAAA | Part (forelimbs) | Private collection | Supplied by Marco Greco (Ambras Greco SAS) of Milan, Italy | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 75 | 130 | 0.0089 | 0.11 | 1,000 |

| R | M-3016 | Part (forelimb, torso) | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | IAC-NHM; ES & RG | 105 | 195 | 0.0092 | 0.06 | 354 |

| S | M-1273 | Part (forelimbs) | Private collection | Owned by Ettore Morone of Torino, Italy | Dominican Republic | IAC-NHM; ES & RG | 105 | 195 | 0.0068 | 0.06 | 354 |

| T | SMNS Do-5742 | Part (body, no head) | Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany | Donated by Georg Dommel of Düsseldorf, Germany in 1980 | Dominican Republic | CNS; ES | 50 | 165 | 0.0308 | 0.11 | 1,415 |

Information is provided on state of preservation (elements preserved); current location and locality of origin (including the mine, where known); and X-ray microcomputed tomography scan settings, with information on where the scan was done and by whom. Fossil O, originally scanned at University of Texas, was rescanned at Harvard at a higher resolution for this project (data from the higher resolution scan were used for the morphometric and phylogenetic analyses). Three fossils previously were published: A(18), I(15), and N(19).

Fig. 1.

Fossil anole lizards preserved in amber. Some of the fossils in this study are exceptionally well preserved (A–C). From X-ray micro-CT scanning, the skeleton can be reconstructed in 3D, revealing complete skeletons (B), fully articulated skulls (C), and fragments (D). The external surface of the lizard is sometimes outlined in the amber by air-filled voids, which when reconstructed in 3D reveal details of the body scales (D) and subdigital lamellae (E, Center). Scale detail is also visible through the amber (E, Left and Right). The amber fossils are represented by letters corresponding to those in Fig. 2. Animations of the 3D reconstructed fossils are in Movie S1.

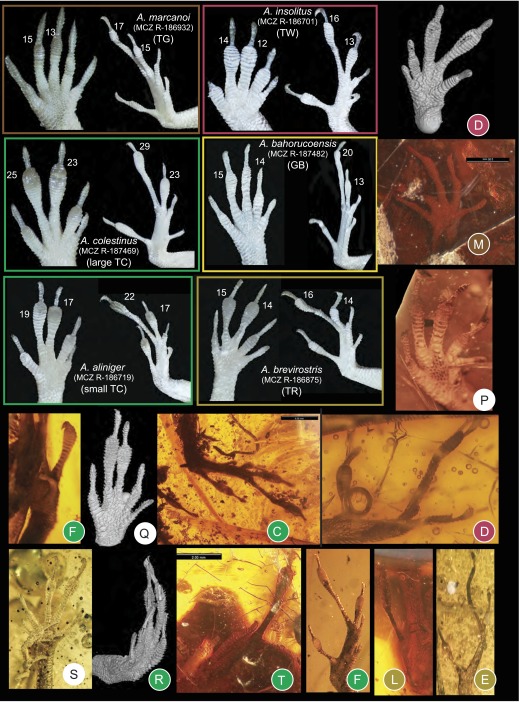

Fig. S1.

Toepad morphology of fore- and hindfeet among recent (representing five ecomorphs) and fossil anoles. Lamella numbers for the modern species are given beside digits III and IV. The amber fossils are colored by ecomorph according to DFA results if assigned with a probability greater than 0.90 (Table S3). Modern specimens from Museum of Comparative Zoology Reptile collection, Harvard University (prefix MCZ R).

We used X-ray micro-CT, light microscopy, and photographs to examine the amber fossils (Table S1) and preserved specimens of extant Hispaniolan species representing different ecomorphs. We recorded linear measurements of the cranial and postcranial skeleton and counts of the number of toepad lamellae (Table S2), which are known to correlate with microhabitat use in extant anoles (21), to test the hypothesis that Miocene Hispaniolan anoles filled the same ecological niches as their extant counterparts. Discriminant function analysis (DFA) was used to assign fossils to ecomorph category using body size-corrected morphometric data and lamella number for extant taxa, with fossils assigned a posteriori. Then we used the reconstructions and direct observations to score the amber fossils for morphological characters traditionally used in anole phylogenetics; these characters differ from those used in ecomorphological analyses and do not indicate that members of the same ecomorph class form a clade (22). We inferred the phylogenetic relationships of the fossils to extant species to test whether the fossils are members of clades representing the same ecomorphs present on Hispaniola today.

Table S2.

Measured and estimated body size (SVL), morphometric variables (in mm), and meristic counts taken from each amber specimen and used in the discriminant function analyses (DFAs) presented in Table S3

| Specimen | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T |

| Measured SVL | 23.8 | 30.0 | 52.8 | 30.2 | 25.7 | 23.2 | 25.4 | 23.1 | ||||||||||||

| SVL estimate from lumbar length | 25.7 | 27.1 | 24.4 | 24.2 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 26.3 | |||||||||||||

| SVL estimate from ilium length | 27.6 | 53.6 | 17.7 | 21.8 | 23.0 | 21.8 | 29.6 | 25.1 | ||||||||||||

| SVL estimate from body length | 24.8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| SVL estimate from mandible length | 28.2 | 27.7 | 27.5 | 24.2 | 21.1 | 21.5 | 20.6 | 21.2 | 19.7 | |||||||||||

| SVL estimate from other (see notes) | 19.4–21.0 | 19.9–21.7 | 18.5–20.0 | 25.2–44.7 | 19.9–28.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Mandible length | 8.63 | 8.46 | 8.40 | 7.40 | 6.43 | 6.97 | 6.57 | 6.29 | 6.57 | 6.00 | ||||||||||

| Premaxilla length | 1.23 | 1.06 | 1.29 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.02 | ||||||||||||

| Maxilla length | 4.20 | 5.40 | 5.27 | 4.52 | 4.13 | 3.91 | 3.55 | 3.79 | 3.64 | |||||||||||

| Skull width | 4.13 | 4.94 | 4.88 | 3.80 | 4.23 | 3.80 | 3.64 | 3.63 | 3.70 | |||||||||||

| Frontal width between orbits | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.53 | ||||||||||||

| Prefrontal width | 2.89 | 2.91 | 2.80 | 2.46 | 2.47 | 2.19 | 2.58 | |||||||||||||

| Orbit diameter | 3.38 | 3.47 | 3.50 | 3.31 | 2.84 | 3.04 | 2.96 | 2.90 | 2.90 | |||||||||||

| Snout length | 3.65 | 3.81 | 3.73 | 3.01 | 2.59 | 2.73 | 2.15 | 2.51 | 2.35 | |||||||||||

| Mandible width | 3.53 | 6.80 | 4.12 | 4.20 | 3.24 | 3.38 | 3.30 | 3.13 | 3.15 | |||||||||||

| Jugal height | 1.92 | 1.81 | 1.58 | 1.52 | 1.68 | 1.50 | 1.36 | 1.54 | 1.62 | |||||||||||

| Sternum width | 2.29 | 1.82 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Humerus length | 4.38 | 9.00 | 3.17 | 3.20 | 3.48 | 4.64 | 3.40 | |||||||||||||

| Ulna length | 3.62 | 7.80 | 3.72 | 2.95 | 2.72 | 2.79 | 2.60 | 3.03 | 2.57 | 4.18 | 3.13 | 2.70 | ||||||||

| Foretoe IV length | 4.83 | 1.64 | 2.47 | 2.16 | 1.93 | 2.18 | 1.77 | 2.46 | 1.88 | |||||||||||

| Foretoe III length | 5.17 | 1.90 | 2.83 | 2.43 | 2.40 | 2.33 | 2.03 | 2.93 | 2.18 | |||||||||||

| Pelvis width | 2.38 | 2.25 | 2.12 | 1.47 | 2.46 | |||||||||||||||

| Sacrum width | 2.00 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 2.52 | 1.92 | 1.62 | ||||||||||||||

| Pubis length | 2.48 | 1.78 | 1.70 | 2.45 | 1.96 | |||||||||||||||

| Femur length | 6.05 | 5.70 | 12.45 | 3.23 | 4.85 | 6.26 | 5.95 | 4.56 | 4.88 | 4.74 | 8.04 | 7.15 | ||||||||

| Tibia length | 4.89 | 5.24 | 10.98 | 2.44 | 4.44 | 5.35 | 4.56 | 4.02 | 4.38 | 4.22 | 6.75 | 6.21 | 4.29 | |||||||

| Metatarsal IV length | 3.37 | 3.16 | 6.40 | 1.73 | 2.72 | 3.04 | 2.92 | 2.74 | 2.83 | 2.80 | 3.88 | 3.80 | 2.84 | |||||||

| Hindtoe IV length | 4.72 | 5.16 | 9.80 | 3.10 | 4.38 | 4.89 | 4.63 | 4.54 | 4.61 | 4.13 | 6.34 | 4.42 | ||||||||

| Hindtoe III length | 2.53 | 5.54 | 1.66 | 2.31 | 2.82 | 2.56 | 2.49 | 2.41 | 3.65 | 3.30 | ||||||||||

| Hindtoe IV lamellae | 14 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 17 | |||||||||||||||

| Hindtoe III lamellae | 23 | 26 | 16 | 18 | 23 | 21 | 19 | 23 | 17 | |||||||||||

| Foretoe IV lamellae | 16 | 17 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 21 | ||||||||||||||

| Foretoe III lamellae | 13 | 13 | 16 | 20 | 20 |

Regression models of modern species were used to estimate SVL of the fossils from four log-transformed variables: the length of a lumbar vertebra; length of the ilium; body length; and mandible length. Details and equations are given in Methods. All squared correlation coefficients are 0.96, except body length, which is 0.99. SVL estimates in bold are those used in the DFAs. When more than one estimate was available, the value chosen was decided according to the preservation of the fossil. Rows 1–6 provide a range of SVL estimates: specimen A broken, measured SVL an underestimate; specimen C incomplete, measured SVL an underestimate; specimen D incomplete, ilium fragment preserved; specimen G incomplete, measured SVL an underestimate; specimen H broken, measured SVL an underestimate; specimen K, other SVL estimated from range of ecomorph-specific slopes for mandible length; specimen N, other SVL estimated from range of ecomorph-specific slopes for mandible length; specimen O, other SVL estimated from range of ecomorph-specific slopes for mandible length; specimen P, other SVL estimated from range of ecomorph-specific slopes for ulna length (r2 = 0.84); specimen S, other SVL estimated from range of ecomorph-specific slopes for ulna length (r2 = 0.84).

Results and Discussion

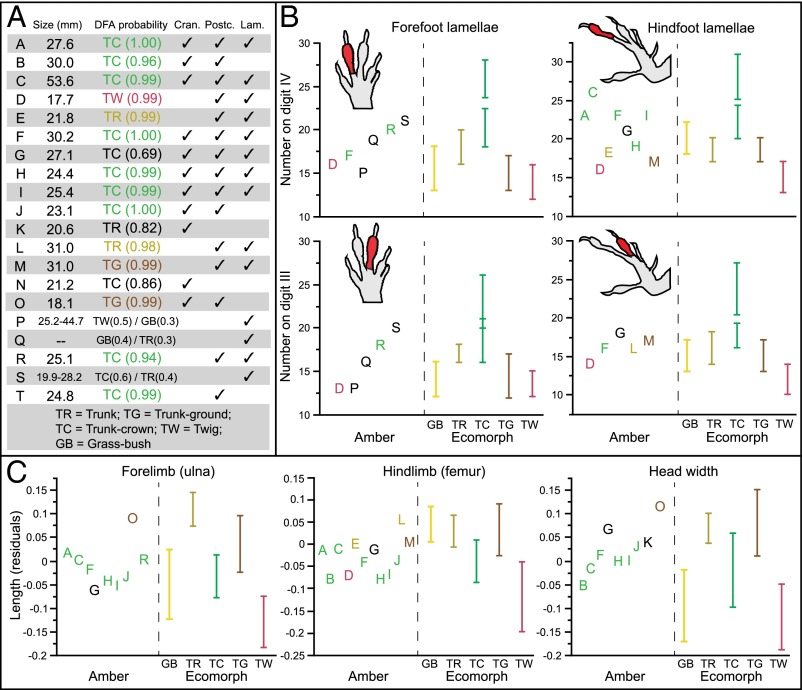

The fossils vary substantially in number of lamellae and body proportions and represent a large portion of modern ecomorphological diversity (Fig. 2 and Figs. S1–S4). Fourteen fossils are assigned to an ecomorph class with high probability (greater than 0.90; Fig. 2A and Table S3). Of these, nine are assigned to the trunk-crown ecomorph: seven complete skeletons, five with preserved lamellae (A, C, F, H, I) and two without (B and J); one headless body (T); and a fragmentary fossil with forelimb lamellae preserved (R). As with modern-day trunk-crown species, which are found high on tree trunks and in the canopy, these fossils have relatively short limbs and long, narrow heads. Extant Hispaniolan trunk-crown anoles exhibit considerable variation in toepad lamella number (23), with smaller-bodied species having fewer lamellae than larger-bodied species (Fig. 2B). Our results suggest that species of both size classes are present in the amber fossil record, the smaller being more common in our sample (e.g., A, F, H, I, and R).

Fig. 2.

Amber fossils exhibit morphometric and meristic variation, which corresponds to variation among the modern ecomorphs. (A) Results of discriminant function analyses (DFA) conducted separately on each fossil. Columns indicate variables present in each fossil: estimated size (snout-vent length), cranial (Cran.), and postcranial (Postc.) measurements and lamella number (Lam.); additional details are given in Table S2. A subset of the variables are displayed to illustrate variation among the fossils and how it corresponds with variation among the ecomorphs (B and C). Amber fossils are colored according to the DFA results (if assigned with greater than 0.90 probability). (B) Variation in the number of subdigital lamellae on the fore- and hindfeet of the amber fossils is shown alongside the range (bars) for each ecomorph. Large and small trunk-crown species also differ in lamella number (Fig. S1). (C) Size-corrected residuals of ulna and femur length and head width. The DFA results can be understood by examining character variation. For example, for amber fossil C, the trunk-crown ecomorph is the only one for which all measurements fall within the range for the present-day species. All cranial and postcranial variables are illustrated in Figs. S3 and S4, which should be consulted to understand fully the DFA classification of some of the fossils.

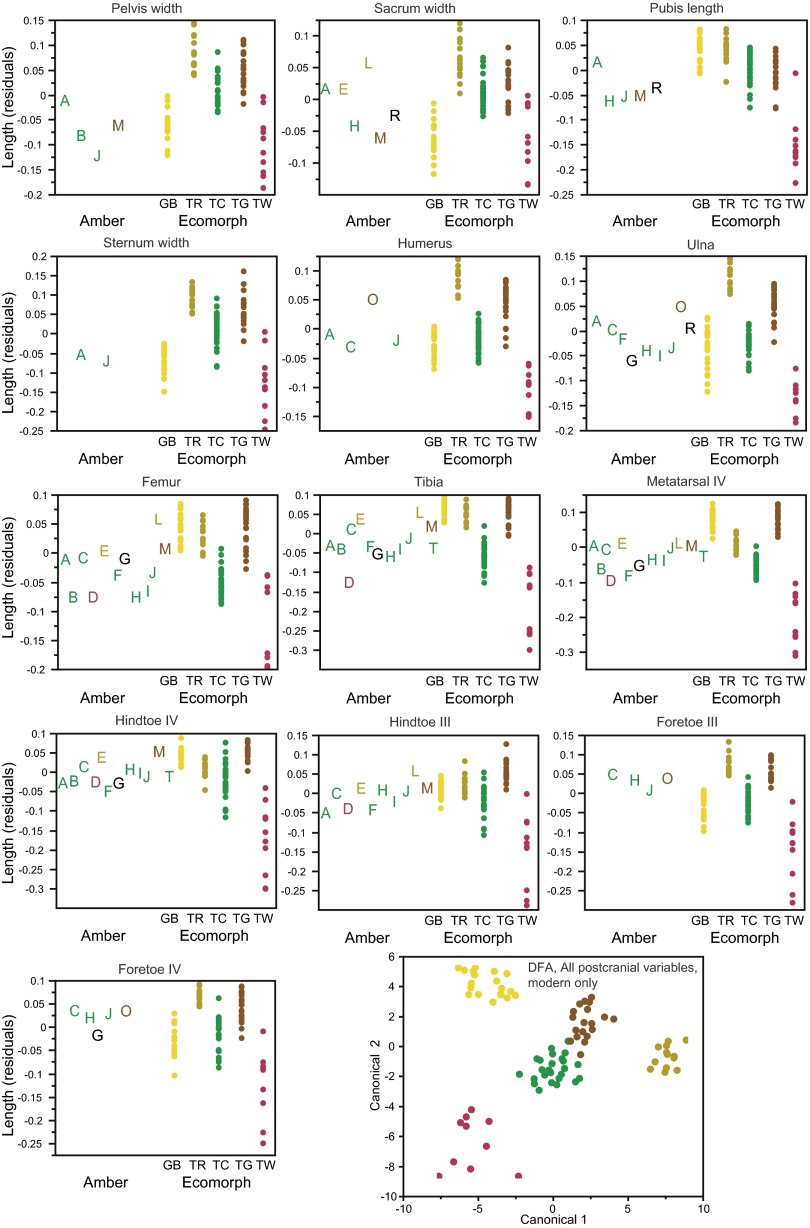

Fig. S4.

Variation among the fossils and how it corresponds with variation among the ecomorphs for all 13 postcranial measurements. Size-corrected residuals are plotted for the amber (A–T) and modern specimens. Amber fossils are colored according to the discriminant function analysis (DFA) results (Table S3) when assigned with a probability greater than 0.90. A plot of the first two canonical variables of the DFA using all 13 variables (Lower Right) illustrates how well the postcranial measurements discriminate the ecomorphs (modern specimens only).

Table S3.

Results of discriminant function analyses (DFAs) using size-corrected residuals of the morphometric variables (details of the size correction in Table S2)

| Specimen | TC | TR | TG | TW | GB | λ | Approximate F (df) | Percent misclassified |

| A | 1.00 | 0.00002 | 40.50 (84, 227.59) | 0 | ||||

| B | 0.96 | 0.00099 | 35.25 (44, 304.19) | 0 | ||||

| C | 1.00 | 0.00018 | 50.11 (44, 258.28) | 0 | ||||

| D | 0.99 | 0.00256 | 28.33 (36, 260.31) | 1.22 | ||||

| E | 1.00 | 0.00148 | 46.78 (28, 257.42) | 0 | ||||

| F | 1.00 | 0.00004 | 41.46 (72, 238.29) | 0 | ||||

| G | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.00004 | 44.46 (68, 241.70) | 0 | |||

| H | 0.99 | 0.00002 | 40.26 (84, 227.59) | 0 | ||||

| I | 0.99 | 0.00037 | 45.59 (40, 259.70) | 0 | ||||

| J | 1.00 | 0.00004 | 34.31 (88, 243.69) | 0 | ||||

| K | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.01746 | 18.97 (32, 304.00) | 7.4 | |||

| [0.81] | [0.18] | 0.02303 | 16.91 (32, 304.00) | 13.8 | ||||

| L | 0.98 | 0.00227 | 49.70 (24, 252.39) | 1.22 | ||||

| M | 1.00 | 0.00075 | 36.86 (40, 259.70) | 2.4 | ||||

| N | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.02797 | 18.21 (28, 300.68) | 5.3 | |||

| [0.52] | [0.48] | 0.03315 | 16.88 (28, 300.68) | 10.6 | ||||

| O | 1.00 | 0.00122 | 26.99 (48, 275.54) | 1.1 | ||||

| [0.99] | 0.00183 | 23.75 (48, 275.54) | 1.1 | |||||

| P | {0.13) | {0.49} | {0.34} | 0.22769 | 20.81 (8, 152.00) | 42.7 | ||

| Q | {0.31} | {0.13} | {0.20} | {0.35} | 0.22769 | 20.81 (8, 152.00) | 42.7 | |

| R | 0.94 | 0.00626 | 43.90 (20, 243.06) | 3.7 | ||||

| S | {0.60} | {0.35} | 0.22769 | 20.81 (8, 152.00) | 42.7 | |||

| T | 0.99 | 0.04449 | 43.50 (12, 233.12) | 24.2 |

Probabilities of classification to the five ecomorphs are presented, with a post hoc Wilks’ λ test of the null hypothesis that the means of all of the independent variables are equal across groups (F statistic and degrees of freedom), and proportion of individuals misclassified in each analysis. Probabilities below 0.1 are not shown. Each DFA used a different set of variables specific to the fossil (Table S2). For three fossils that comprised an isolated skull (K, N, and O), a second DFA using raw (not size-corrected) variables was conducted, the results of which are given in brackets. For fossils P, Q, and S, only lamella counts were available for the DFA, so these results are given in braces. Bold indicates DFA probabilities above 0.90.

Modern trunk-ground species are generally found around the bases of trees and have broad, short heads, long hindlimbs, intermediate-length forelimbs, and narrow toepads with few to intermediate numbers of lamellae (on toes of the fore- and hindfeet, respectively). Two fossils are assigned with high probability to the trunk-ground ecomorph: one relatively long-limbed partial skeleton with an intermediate number of lamellae (M) (Fig. 2 B and C and Figs. S1 and S4), and a second (O) composed of a broad skull associated with an intermediate-length forelimb (Fig. 2C and Figs. S2–S4).

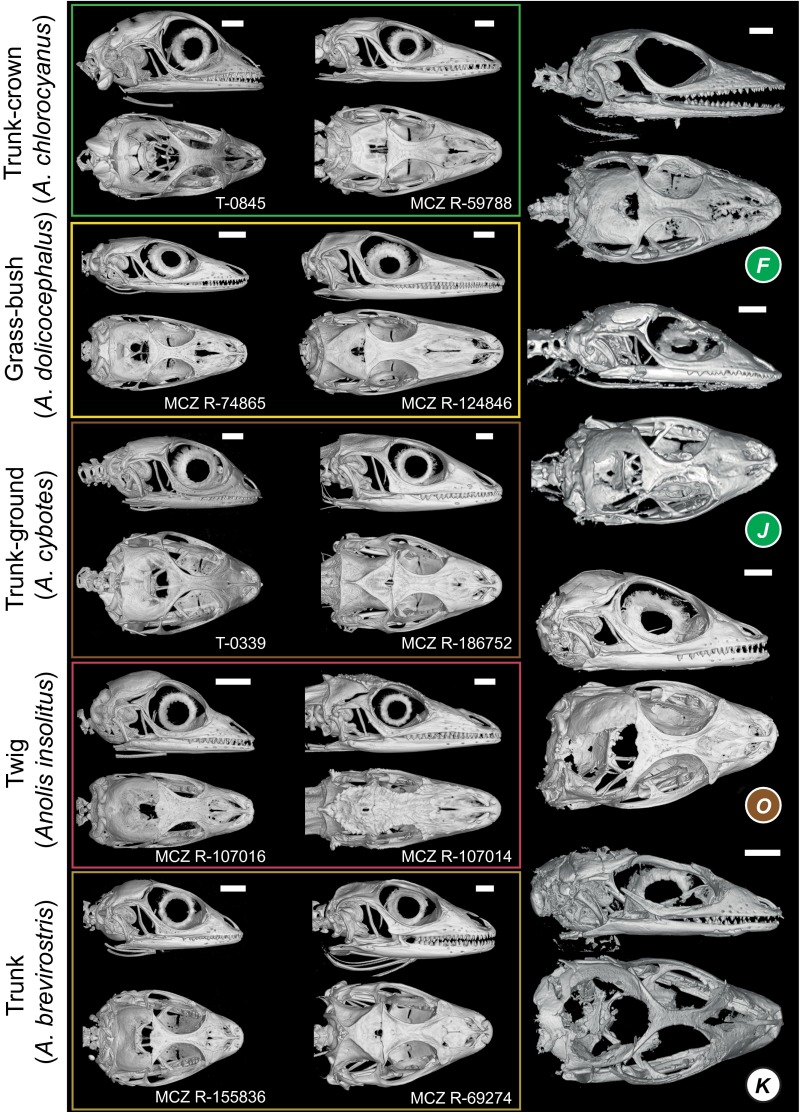

Fig. S2.

Cranial shape of five recent anoles representing five ecomorphs compared with four amber fossils. Crania of modern juveniles (Left) and adults (Center), as well as amber fossil skulls (Right) are shown in lateral and dorsal views. The amber fossils are colored by ecomorph if assigned with a probability greater than 0.90 (Table S3). Modern specimens from Museum of Comparative Zoology Reptile collection, Harvard University (prefix MCZ R), or Field Tag for T.J. Sanger (prefix T).

Members of the trunk ecomorph are found on broad tree trunks and have broad, short heads, long hindlimbs and forelimbs, and hindfoot toepads with intermediate lamella numbers. Two fossils (E and L) have similarly long hindlimbs (with femur and tibia proportionally longer than metatarsal length) and intermediate numbers of lamellae (Fig. 2 B and C and Figs. S1 and S4) and are assigned with high probability to the trunk ecomorph. Last, the fossil with the smallest body size, a headless skeleton with preserved lamellae (D), is assigned to the twig ecomorph. Twig anoles have very short limbs and use very narrow branches. They also have toepads with few lamellae. Fossil D has similarly short limbs and few lamellae (Fig. 2 B and C and Figs. S1 and S4).

The remaining six fossils that preserve substantial skeletal material or soft tissue are not assigned to any ecomorph with high probability (Table S3). Two isolated skulls are assigned with probabilities between 0.80 and 0.90 to the trunk-crown (N) and trunk (K) ecomorphs, respectively, and a complete skeleton with preserved lamellae (G) is assigned to the trunk-crown ecomorph, but with only an intermediate probability (0.69). In these three cases, as with fossils with higher DFA probabilities, the individual morphological characters are consistent with their ecomorph assignments (Fig. 2 and Figs. S3 and S4). Three additional fossils represented by isolated fragments of forelimbs with toepads (P, Q, and S) are assigned to ecomorph classes with low probability. Given that overlap exists among the ecomorphs in lamella number (Fig. 2B), our inability to assign these fossils to a single ecomorph is not surprising, although the observed variation in lamella number indicates that members of more than one ecomorph class may be present in this trio.

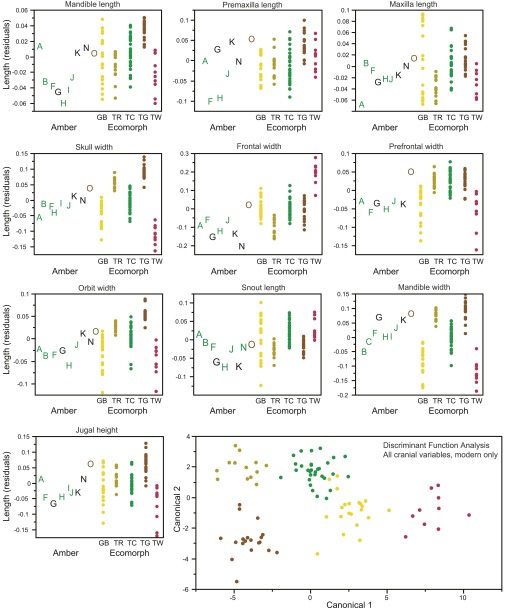

Fig. S3.

Variation among the fossils and how it corresponds with variation among the ecomorphs for all 10 cranial measurements. Size-corrected residuals are plotted for the amber fossils labeled by letters (A–T) and modern specimens (colored dots by ecomorph). Amber fossils are colored according to the DFA results (detailed in Table S3) when assigned with a probability greater than 0.90. A plot of the first two canonical variables of the DFA using all 10 variables (Lower Right) illustrates how well the cranial measurements discriminate the ecomorphs (modern specimens only).

In summary, morphometric analysis places fossils in four ecomorphs with high probability. Completeness of many of the trunk-crown and the two trunk-ground fossils provides confidence in their ecomorph assignments. The presence of key skeletal elements and the distinctive morphology of twig anoles also renders plausible the assignment of fossil D to that class. By contrast, the two fossils assigned to the trunk ecomorph are fragmentary, comprising only hindquarters, and thus their assignment is less certain. Given that some extant Hispaniolan anoles do not conform to any ecomorph class and are similar to trunk anoles in hindlimb dimensions (21, 24), we cannot rule out the possibility that these fossils, although most similar among the ecomorphs to trunk anoles, are not members of any ecomorph class. Regardless of whether these fossils are trunk anoles, the data indicate that at least four ecomorphologically distinct species occurred in Hispaniola in the Miocene. Moreover, based on the numbers of toepad lamellae, our data suggest the existence of two trunk-crown species, likely paralleling the large and small modern-day members of that ecomorph (23). In summary, although to date only one anole species has been described from Dominican amber (15), our data reveal the existence of minimally four additional species.

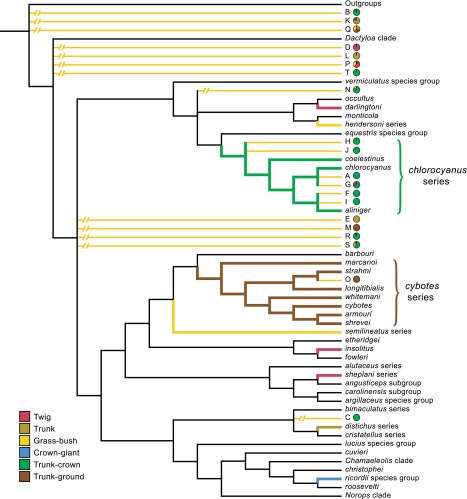

The existence of four ecomorphs in Hispaniola in the Miocene is consistent with molecular dating analyses, which indicate the existence of at least four and possibly six present-day ecomorphs at that time (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, given that each of the anole ecomorphs has evolved multiple times (albeit primarily on different islands), their fossil representatives might not be members of the same ecomorph clades present on Hispaniola today; an alternative possibility is that the fossils represent additional instances of evolution of these ecomorphs in clades that did not persist to the present. We tested this hypothesis by using morphological characters traditionally used in anole phylogenetics (22) to infer the relationships of the fossils to extant species.

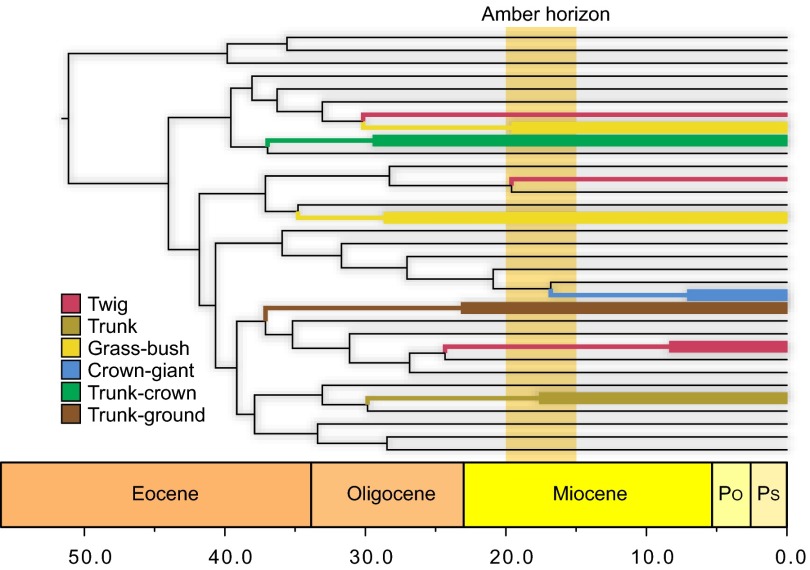

Fig. 3.

Ancient divergence of anole ecomorphs. Six habitat specialists, called ecomorphs, occur on islands in the Greater Antilles today: twig, grass-bush, trunk, trunk-ground, trunk-crown, and crown-giant, named for their characteristic microhabitats and differing morphology, ecology, and behavior. A chronogram of Anolis lizard diversification (55) indicates that Hispaniolan ecomorph clades originated long ago and that most predate the origin of Hispaniolan amber, which was formed at some point within the range indicated by the amber horizon. Hispaniolan clades (highlighted) are colored according to ecomorph, with wide lines indicating crown clades for those containing more than one species. Clades of non-Hispaniolan species have been collapsed (for a full summary, see ref. 56). The Hispaniolan crown-giants are closely related to the crown-giants of Puerto Rico, as well as some non–crown-giants, suggesting the possibility of an earlier origin of the crown-giant condition than indicated here. Po, Pliocene; Ps, Pleistocene.

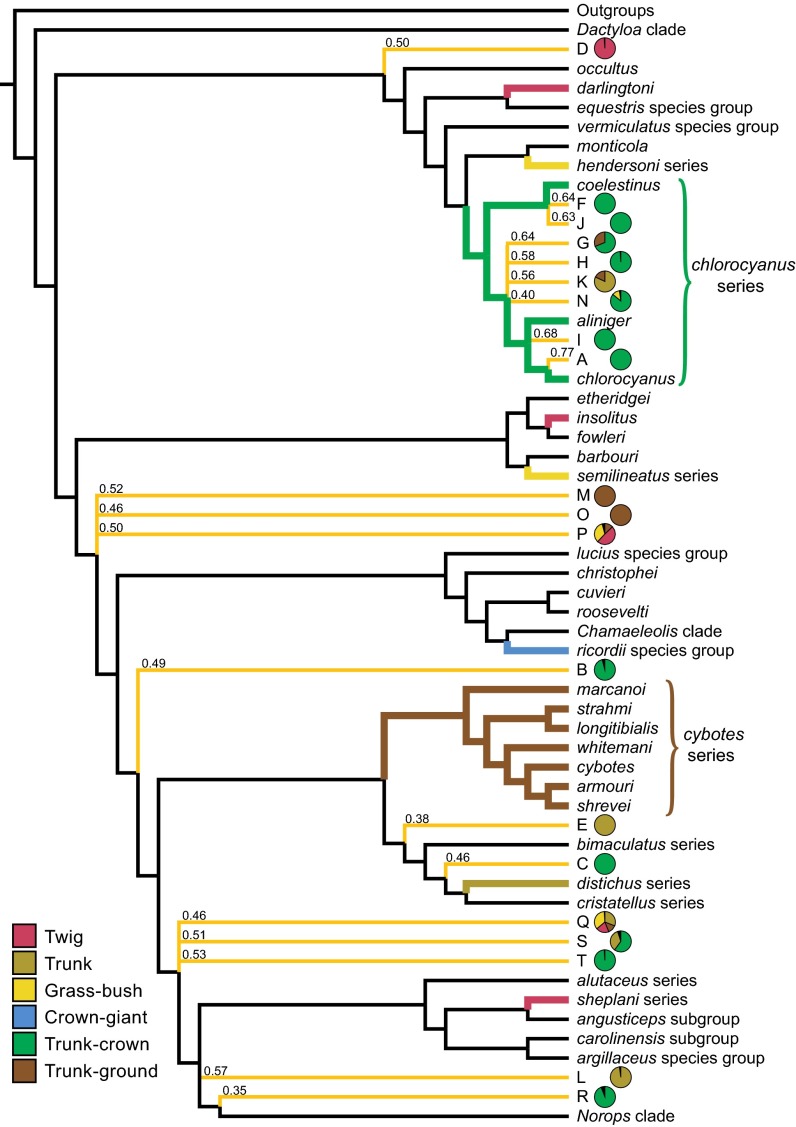

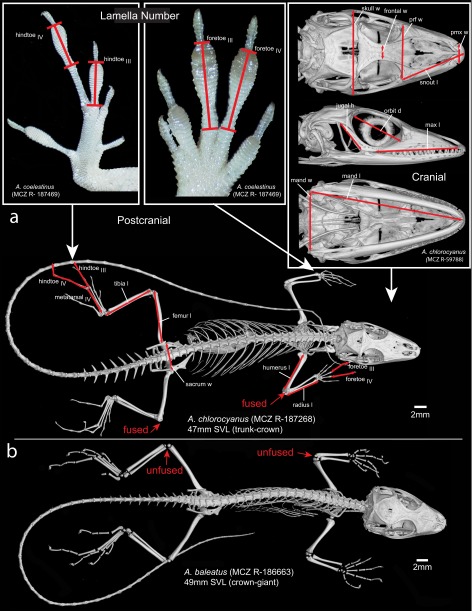

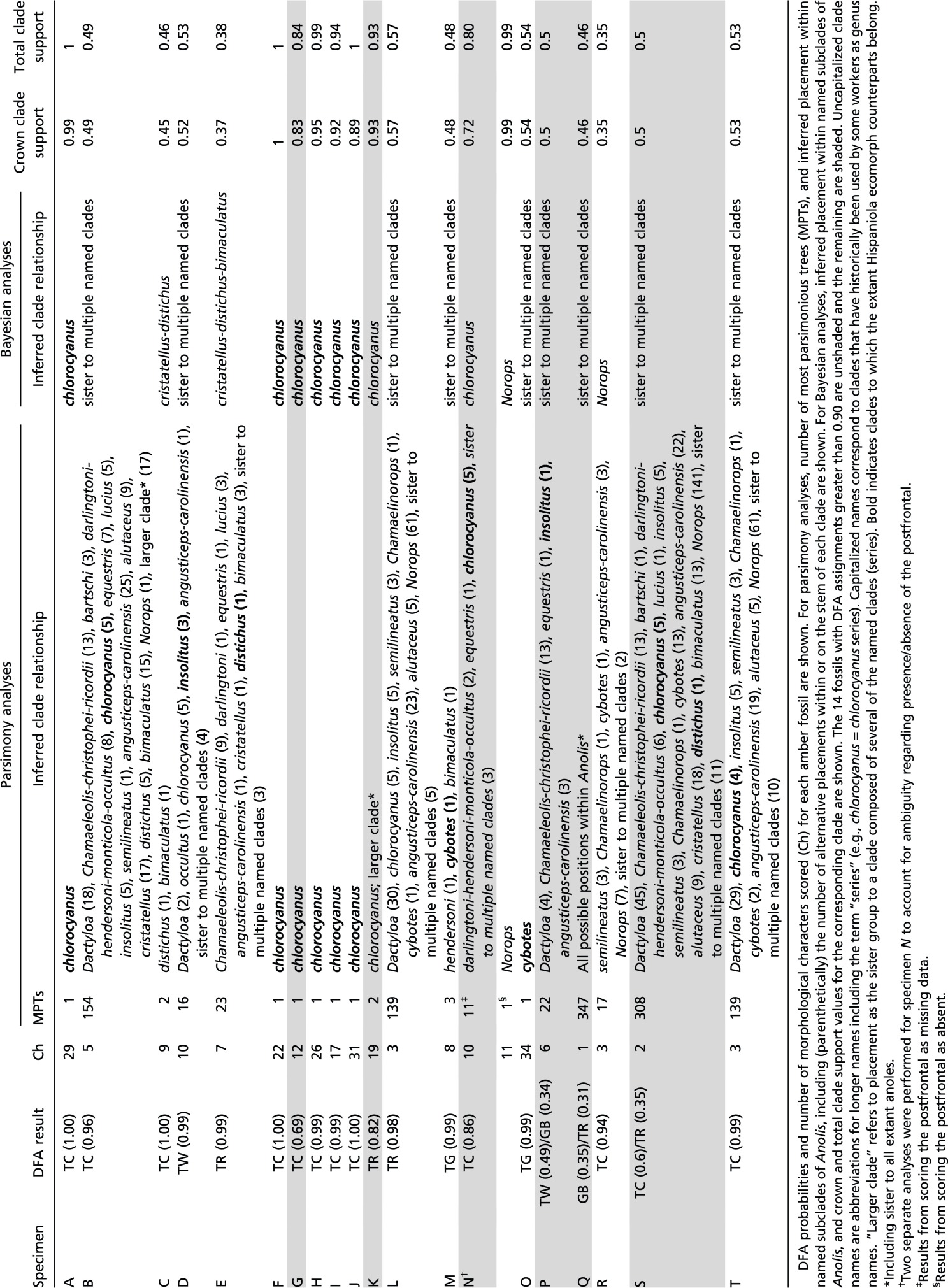

In Bayesian phylogenetic analyses, all 14 fossils with DFA assignments greater than 0.90 were inferred within crown group Anolis (Fig. 4). Parsimony analyses yielded similar results, although one fossil with a high DFA assignment (B) was not inferred within crown group Anolis (Fig. S5). Five fossils identified as trunk-crown anoles with high-probability (A, F, H, I, and J; Fig. 2A and Table S3), were placed with the chlorocyanus series of extant trunk-crown anoles with strong support in Bayesian analyses and unambiguously in parsimony analyses (Fig. 4, Fig. S5, and Table S4). Other fossils identified as trunk-crown anoles (B, C, R, and T) were placed ambiguously in the phylogeny, revealing little about their phylogenetic relationships to their extant ecomorph counterparts. However, in both Bayesian and parsimony analyses, the alternative placements of two of these trunk-crown fossils (B and T) included close relationships with the chlorocyanus clade (Fig. S5).

Fig. 4.

Summary tree showing the phylogenetic relationships of the amber fossils inferred by Bayesian analyses. Names of Anolis subclades are given on the right. The amber fossils are represented by letters corresponding to those in Fig. 2, and their relationships are indicated by yellow-orange branches (see Methods for details). Bayesian posterior probabilities for fossil placements are shown above branches. DFA classifications for the fossils are indicated by pie charts, colored by ecomorph (only probabilities greater than 0.1 are shown).

Fig. S5.

Summary tree showing the phylogenetic relationships of the amber fossils inferred by parsimony analyses. Names of Anolis subclades are given on the right. The amber fossils are represented by letters corresponding to those in Fig. 2, and their relationships are indicated by yellow-orange branches; broken branches indicate the prune and graft results of alternative placements. DFA classifications for the fossils are indicated by pie charts, colored by ecomorph (only probabilities greater than 0.1 are shown).

Table S4.

Results of parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses

|

Phylogenetic results were inconclusive for fossils identified with high probability as trunk-ground, trunk, and twig anoles. However, in all but one case (L), Bayesian and parsimony results both indicated the possibility of close relationships between fossils and Hispaniolan clades to which their extant ecomorph counterparts belong. For the two trunk-ground fossils (M and O), Bayesian results included membership in the trunk-ground cybotes series among possible placements (Fig. 4 and Table S4), a relationship that was even more strongly supported in parsimony analyses (cybotes series membership of fossils M and O in 1/3 and 1/1 most parsimonious trees, respectively; Fig. S5). Likewise, trunk ecomorph fossils (E and L) were inferred in the trunk specialist distichus series, and the twig ecomorph fossil (D) was inferred as sister to the twig specialist insolitus, in some of the many credible phylogenetic trees (Table S4; although fossil L only grouped with the distichus clade in the Bayesian analysis). The relatively few available morphological characters (n = 91) used in anole phylogenetics and the partial nature of the character data for these fragmentary fossils both likely contribute to the uncertain phylogenetic placement of many of these specimens. Overall, the phylogenetic results are congruent with the close relationships of the fossils to extant species representing the same ecomorphs. These results support the hypothesis that the anole ecomorphs evolved early in the Caribbean adaptive radiation and that anole community structure has been stable ever since.

Just as interesting as the ecomorphs present in the amber fauna are those that are absent. Crown-giants hatch at a size considerably larger than other anoles, and the lack of large fossils with juvenile characteristics (18) (Fig. S6B) indicates that no crown-giant anoles were present in our sample. Given that the similarly arboreal trunk-crown anoles were preserved in great numbers, habitat use does not explain the absence of crown-giants. One possibility, of course, is that crown-giants are too large to become trapped in resin. In addition, crown-giants tend to be less common than members of other ecomorphs, and thus their absence may be a reflection of their abundance. A last possibility, however, is that crown-giant anoles may not have occurred on Hispaniola when the amber fossils were formed; molecular dating (25) places the stem age of the ricordii species group, which contains extant Hispaniolan crown-giants, at 17 My, possibly younger than the formation of Dominican amber (Fig. 3). By contrast, molecular divergence time estimates indicate that the other five ecomorphs clearly evolved substantially earlier than the formation of the amber deposits (Fig. 3). In this light, the absence of grass-bush anoles is somewhat surprising. Small and occurring low in the vegetation, we might have expected them to become entrapped in amber. On the other hand, as their name implies, these lizards usually are found on surfaces other than tree trunks, and thus habitat use may account for their absence in our sample.

Fig. S6.

Schematic of the morphometric measurements and meristic counts taken from fossil and recent anole specimens shown on an adult trunk-crown anole (A). A juvenile crown-giant anole (B) of approximately the same SVL. Red arrows point to where there are clearly unfused (B) and fused (A) epiphyses and diaphyses of fore and hindlimb bones, which allow the identification of juveniles vs. adults. Specimens from Museum of Comparative Zoology Reptile collection, Harvard University (prefix MCZ R).

Evolutionary interpretations from phylogenetic analyses of extant species are always haunted by the specter of extinction, but our data provide little evidence for dimensions of anole diversity not suggested by analyses on the contemporary fauna. Quite the contrary, the fossil data and phylogenetic comparative analyses are entirely congruent in suggesting that the ecomorph radiation is ancient and that the ecomorphs evolved early and have remained in place ever since (9). This is not to say that no adaptive diversification has occurred in anoles since the Miocene. Rather, there has been considerable subdivision of ecomorph niches as species specialize for different thermal microhabitats (26)—unfortunately, the scalation characters that tend to correlate with thermal biology (27) were not preserved in most fossils, preventing inferences about the evolution of thermal specialization. Our data do confirm, however, that the subsequent division of the trunk-crown anole niche into small and large species, presumably to partition prey resources (21), also has an ancient origin, again in agreement with molecular divergence estimates.

Caribbean islands are a hotspot of biological diversity, and research on their flora and fauna has contributed immensely to our understanding of evolutionary processes. The abundance of invertebrates preserved in amber from the Caribbean and other geographical regions has led to macroevolutionary and macroecological insights about some groups (28–30), but such approaches have not previously been possible for vertebrates. The Caribbean island Anolis lizards have contributed to our understanding of evolutionary processes as a well-known case of adaptive radiation. However, until now there has been a hole in our understanding of this system because of a dearth of fossil evidence of their evolutionary past. Our analysis of the diversity of the Miocene fauna of Hispaniola reveals that anole community structure has remained much the same for at least the last 20 My, providing strong evidence for the stability of communities across long periods of time during which substantial environmental change has occurred. Whether these results are paralleled in other Caribbean groups remains to be seen; emerging fossils (16, 31) of a radiation of gekkonid lizards may prove an interesting comparison.

Methods

Specimens.

The fossils included in this study are identified as belonging to the Anolis clade by the presence of one or more of the following derived character states: coronoid labial blade, slender clavicles, reduction or absence of the splenial and angular bones, no ribs on cervical vertebrae 3 and 4, three sternal ribs, no ribs on three or more (up to seven) posterior presacral vertebrae, transverse processes of caudal vertebrae located posterior to fracture planes, and expanded subdigital scales that form a pad under (at least) the antepenultimate phalanges of digits II–V (32).

Thirty-eight amber fossils were available for study (3 previously described and 35 new). To qualify for inclusion in the ecomorphological analysis, the fossil had to have at least two of the three data types (cranial, postcranial, lamella number), or, if only one type was available, at least two toes with preserved lamellae, or three skeletal elements and an estimated snout-to-vent length (SVL) with which to size-correct the data. Therefore, 20 amber fossils (Table S1) were available to compare with 15 species representing the main clades and ecomorphs extant on Hispaniola: A. aliniger (trunk-crown, TC), A. chlorocyanus (TC), A. coelestinus (TC), A. singularis (TC), A. brevirostris (trunk, TR), A. distichus (TR), A. marcanoi (trunk-ground, TG), A. cybotes (TG), A. sheplani (twig, TW), A. placidus (TW), A. insolitus (TW), A. bahorucoensis (grass-bush, GB), A. dolichocephalus (GB), A. hendersoni (GB), and A. olssoni (GB) (100 specimens). For each extant species, males and females spanning the size range from juvenile to adult were sampled from the alcohol-preserved collection at the Museum of Comparative Zoology (Cambridge, MA).

X-Ray Microcomputed Tomography.

The amber fossils and modern species were examined using X-ray micro-CT. Scans were made using Nikon (Metris) X-Tek HMXST 225 machines in Harvard University’s Center for Nanoscale Systems [a member of the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN), which is supported by the National Science Foundation] and The Natural History Museum, London, and supplemented with data from other systems, details of which are given in Table S1. The X-ray micro-CT data were processed using VGStudio MAX v2.2 (Volume Graphics GmbH). The different elements in the fossils (i.e., bone, amber, air) and modern specimens (i.e., bone, soft tissue) were reconstructed in 3D by using different thresholds on the slices for gray values specific to these elements. In some amber pieces, air-filled voids outlined the body of the lizard inclusion (and the soft tissue was mostly degraded), making it possible to examine scale patterns, particularly of the toepads.

Body Size Estimation.

SVL, usually measured as the distance from the tip of the snout to the anterior end of the vent, is commonly used as a proxy for body size in lizards. On a skeleton, the distance is taken from the anterior edge of the premaxilla on the midline to the articulation between the second sacral vertebra and first caudal vertebra. SVL was measured from 3D-rendered skeletons in all modern specimens and on amber fossils where possible, using the polyline tool in VGStudio MAX v2.2 (Volume Graphics), which allows more accurate measurement of distorted specimens by using cumulative points positioned along a line.

SVL could not be measured directly on amber fossils that are missing the skull or parts of the axial skeleton. Therefore, SVL was estimated from the length of other body parts that we found to have minimal variation among ecomorphs using a regression model from the 100 modern specimens, summarized in Table S2. Specifically, we used four approaches:

-

i)

The length of a lumbar vertebra (Lumbar), calculated as the average length of the last two presacral vertebrae, scales very strongly with SVL (r2 = 0.96): logLumbar = −1.58223 + 1.0032746 × logSVL.

-

ii)

The length of the ilium (Ilium), measured from the posterior tip of the shaft to the anterior tip of the anterior iliac process, also scales very strongly with SVL (r2 = 0.96): logIlium = −1.48835 + 1.23261 × logSVL.

-

iii)

Body length (BL), measured from the anterior edge of the atlas to the posterior edge of the last sacral vertebra medially along the ventral side of the external body from the narrowest point of neck region to the vent, scales the most strongly with SVL (r2 = 0.99): logBL = −0.299015 + 1.0836932 × logSVL.

-

iv)

Mandible length (MandL), measured from the posteriormost point on the retroarticular process to the anterior most part of the dentary at the symphysis, scales very strongly with SVL (r2 = 0.96): logMandL = −0.521892 + 1.0051243 × logSVL.

For many of the fossils, SVL was measured or estimated by several different methods (Table S2). The estimated SVL used for size correction was assessed on a fossil-by-fossil basis, using the most reliable measurement given the state of preservation of the specimen. For the more fragmentary fossils (K, N, O, P, and S), for which approaches i–iii above could not be used, we also provide a range of SVL estimates (Table S2). The ranges were estimated from the distribution of ecomorph-specific slopes constituting various body measurements. For example, in fossils with isolated heads (K, N, and O), the range of possible SVLs was taken from the ecomorph slopes with the lowest and highest intercept in regressions of mandible length, mandible width, and/or skull width. For fossils P and S, the range of SVLs were predicted using ulna length (r2 = 0.84; logUlna = −1.195832 + 1.205887 × logSVL). Fossil P has a well-defined dewlap, indicating maturity, and would suggest a larger animal of an ecomorph made up predominantly of species of small body size, such as twig anoles (44.7 mm using twig-specific slope). Fossil S has unfused epiphyses, suggesting a juvenile.

Morphometric Analysis.

To compare the morphology of extant and fossil anoles, we collected cranial and postcranial measurements from reconstructed skeletons using X-ray micro-CT. We counted the number of subdigital lamellae in some amber fossils from reconstructed soft tissue using X-ray micro-CT; lamellae of other amber fossils and alcohol-preserved modern specimens were counted using stereomicroscopes. Variables measured for each amber fossil are given in Table S2. Cranial shape variation was captured using ten linear measurements (Fig. S6A): skull width, frontal width, prefrontal width, snout length, premaxilla width, jugal height, orbit diameter, maxilla length, mandible width, and mandible length. These measurements reflect much of the cranial variation among ecomorphs (33, 34). Postcranial measurements reflect those known to vary among ecomorphs, the adaptive significance of which is well understood (24, 34): lengths of the humerus, ulna, femur, tibia, fourth metatarsal, third and fourth toes of the fore- and hindfeet, widths of the sternum, pelvis and sacrum, and pubis length. Numbers of lamellae were counted for the third and fourth toes of the fore- and hindfeet.

Cranial and postcranial measurements (Table S2) were corrected for body size by using the residuals from separate linear regressions of log-transformed cranial and postcranial metrics on log-transformed SVL. We evaluated the probability of assignment of each fossil to the ecomorph classes using DFA. Because of variation in which elements were preserved in the fossils, DFAs were performed separately for each fossil (Table S3). In each case, a DFA was performed using variables from the modern specimens, which included only the variables that were also available for the fossil, and the assignment of a fossil to an ecomorph was determined based on this subset of variables from modern specimens. DFA was performed using a common (within-) covariance matrix for all groups (linear DA) in JMP Pro v.10 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Phylogenetic Analysis.

We scored the 20 amber fossils for the morphological characters used by Poe (22) to infer anole phylogeny, using X-ray micro-CT scans, photographs, and direct observations. Morphometric measurements (characters 1–9 in ref. 22) were not included in the data matrix because the absence of minimum and maximum values in Poe’s (22) character descriptions precluded the addition of new information. Data for 13 morphological characters (characters 12, 55–57, 59, 65–66, 71, 74–75, 78–79, and 90 in ref. 22) were not included for fossils, except C, the only likely adult, because at least one of the states for these characters develops late in ontogeny and thus would not have been present for fossils other than C. These data were combined with morphological (22) and molecular data [ND2, COI, and RAG1 genes, 5 transfer RNAs, and the origin for light-strand replication (35–45)] for extant species. Molecular data were aligned using ClustalX (46) and translated into amino acids using MacClade v. 4.07 (47) to confirm the correct translation frame. Sequence coding for transfer RNAs was aligned manually following Kumazawa and Nishida’s (48) model of tRNA secondary structure. One hundred bases corresponding to sections of the tRNAs and the origin of light-strand replication were excluded from the analyses due to ambiguous alignment. The final matrix analyzed included 4,873 bases, 91 morphological characters, and 181 extant taxa (174 Anolis and 7 outgroup species). All 181 species were scored for morphological characters; 140 also had molecular data. The resulting data matrix was analyzed using parsimony and Bayesian methods.

To reduce the computational time that results from large amounts of missing data in the amber fossils, we inferred a topology for the extant species and then used that topology as a backbone topological constraint (which allows species not included in the constraint tree to be placed freely in the topology) to infer the phylogenetic position of the amber fossils. The topology for the extant species was inferred with PAUP* v. 4.0b10 (49) using parsimony on the combined dataset (181 species: 91 morphological characters and 4,873 DNA bases). We used equal costs for state transformations, except for multistate ordered morphological characters, which were weighted such that the range of each character equals 1. We performed 2,000 replicates of random stepwise addition, with default settings for all other options.

We then performed a separate parsimony analysis for each amber fossil by including each fossil in the combined matrix for the extant species, imposing the topological constraint, and using a single replicate of random stepwise addition (other options left on default settings). We combined the results for all of the fossils in a single summary tree (Fig. S5). For fossils for which a single most parsimonious tree (MPT) was inferred, the fossil was placed in that position in the summary tree. For fossils for which more than one MPT was inferred, we used a prune and regraft consensus method (50), placing each fossil at the basal node of the least inclusive clade in the backbone constraint tree that included all of the alternative placements of the fossil.

To perform Bayesian analyses, we first rescored the morphological characters in the combined matrix into ordered or unordered characters consisting of 6 or 10 character states, respectively [following Poe’s (22) character descriptions]. We then followed a similar approach to that used in the parsimony analyses. First, we estimated a topology of extant species (to be used as the equivalent of a backbone constraint), by analyzing the extant combined matrix in MrBayes v. 3.2.3 (51). We executed four independent runs of 50 million generations with a random starting tree, a sampling frequency of 1,000 generations, and remaining parameters left at default values. We partitioned data by morphology, codon position, and tRNAs (11 partitions) and estimated the model for each partition using jModeltest v. 2.1.4 (52). To confirm an appropriate sampling interval and that stationarity was achieved after discarding the first 25% of the sampled trees, we examined effective sample size values using TRACER v1.5 (53), compared the average SD of split frequencies between chains, and examined thepotential scale reduction factor (PSRF) of all of the estimated parameters for the four runs combined. We estimated a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree and created a series of partial constraints so that we could enforce the MCC topology of extant species as a strict constraint in downstream analyses that included fossil taxa. We conducted an independent Bayesian analysis for each fossil, using the same protocol and settings as the extant topology analysis, but with a duration of 15 million generations. After discarding the first 25% of sampled trees, we estimated a majority rule consensus tree for each fossil specimen including all compatible groups (using the contype = allcompat command). We combined the majority rule tree results of all fossils in a single summary tree (Fig. 4).

We used Bayesian topology tests (54) to evaluate support for the placement of individual fossils within extant clades that correspond to the same ecomorph. Topologies representing each of the hypotheses of interest, e.g., fossil D placed as sister to insolitus, were used as filters in PAUP* to examine topologies contained in the 95% credible set of trees resulting from the Bayesian analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank those who allowed us access to amber fossils for study: G. Bechly, J. Calbeto, L. Costeur, M. Cusanovich, G. Greco, M. Greco, D. Grimaldi, M. Halonen, and J. Work. We especially thank E. Morone for providing access to more than half of the fossils examined for this study. We thank J. Klaczko, and G. Gartner for providing support and discussions and J. Casart for assisting with data collection. Scan data were also provided by R. Boistel, M. Polcyn, L. Jacobs, M. Colbert, and R. Ketcham. We thank the National Science Foundation for support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Raw morphometric and phylogenetic data and high-resolution images of the fossils have been archived in Zenodo, https://zenodo.org/record/17442 (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.17442).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1506516112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Williams JW, Shuman BN, Webb T, III, Bartlein PJ, Leduc PL. Late-Quaternary vegetation dynamics in North America: Scaling from taxa to biomes. Ecol Monogr. 2004;74(2):309–334. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons SK. A quantitative model for assessing community dynamics of Pleistocene mammals. Am Nat. 2005;165(6):E168–E185. doi: 10.1086/429699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams JW, Jackson ST. Novel climates, no-analog communities, and ecological surprises. Paleoecol Rev. 2007;5(9):475–482. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blois JL, Hadly EA. 2009. Mammalian response to Cenozoic climatic change. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 37(8):8.1–8.28.

- 5.Olszewski TD. Persistence of high diversity in non-equilibrium ecological communities: Implications for modern and fossil ecosystems. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2012;279(1727):230–236. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brett CE. Coordinated stasis reconsidered: A perspective at fifteen years. In: Talent JA, editor. Earth and Life. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams EE. 1983. Ecomorphs, faunas, island size, and diverse end points in island radiations of Anolis. Lizard Ecology: Studies of a Model Organism, eds Huey RB, Pianka ER, Schoener TW (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA), pp 326–370.

- 8.Losos JB, Jackman TR, Larson A, de Queiroz K, Rodríguez-Schettino L. Contingency and determinism in replicated adaptive radiations of island lizards. Science. 1998;279(5359):2115–2118. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahler DL, Ingram T, Revell LJ, Losos JB. Exceptional convergence on the macroevolutionary landscape in island lizard radiations. Science. 2013;341(6143):292–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1232392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poinar GO. Palaeoecological perspectives in Dominican amber. Ann Soc Entomol Fr. 2010;46(1-2):23–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penney D. Paleoecology of Dominican amber preservation: Spider (Araneae) inclusions demonstrate a bias for active, trunk-dwelling faunas. Paleobiology. 2002;28(3):389–398. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimaldi D. Studies on Fossils in Amber, With Particular Reference to Cretaceous of New Jersey. Backhuys Publishers; Leiden: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacPhee RDE, Grimaldi DA. Mammal bones in Dominican amber. Nature. 1996;380(6574):489–490. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poinar GO, Jr, Cannatella DC. An Upper Eocene frog from the Dominican Republic and its implication for Caribbean biogeography. Science. 1987;237(4819):1215–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.237.4819.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieppel O. Green anole in Dominican amber. Nature. 1980;286(5772):486–487. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daza JD, Bauer AM. A new amber-embedded sphaerodactyl gecko from Hispaniola, with comments on morphological synapomorphies of the Sphaerodactylidae. Breviora. 2012;529:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazell JD., Jr An Anolis (Sauria, Iguanidae) in amber. J Paleontol. 1965;39(3):379–382. [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Queiroz K, Chu LR, Losos JB. A second Anolis lizard in Dominican amber and the systematics and ecological morphology of Dominican amber anoles. Am Mus Novit. 1998;3249:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polcyn MJ, Rogers JV, II, Kobayashi Y, Jacobs LL. Computed tomography of an Anolis lizard in Dominican amber: systematic, taphonomic, biogeographic, and evolutionary implications. Paleontol. Electron. 2002;5(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iturralde-Vinent MA. Geology of the amber-bearing deposits of the Greater Antilles. Caribb J Sci. 2001;37(3/4):141–167. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Losos JB. Lizards in an Evolutionary Tree: Ecology and Adaptive Radiation of Anoles. Univ of California Press, Berkeley; CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poe S. Phylogeny of anoles. Herpetological Monogr. 2004;18(1):37–89. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams EE. The species of Hispaniolan green anoles (Sauria, Iguanidae) Breviora. 1965;227:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beuttell K, Losos JB. Ecological morphology of Caribbean anoles. Herpetolog Monogr. 1999;13:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burbrink FT, Pyron RA. How does ecological opportunity influence rates of speciation, extinction, and morphological diversification in New World ratsnakes (tribe Lampropeltini)? Evolution. 2010;64(4):934–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hertz PE, et al. Asynchronous evolution of physiology and morphology in Anolis lizards. Evolution. 2013;67(7):2101–2113. doi: 10.1111/evo.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wegener JE, Gartner GEA, Losos JB. Lizard scales in an adaptive radiation: Variation in scale number follows climatic and structural habitat diversity in Anolis lizards. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2014;113(2):570–579. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson EO. Invasion and extinction in the West Indian ant fauna: Evidence from the Dominican amber. Science. 1985;229(4710):265–267. doi: 10.1126/science.229.4710.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penney D, Langan AM. Comparing amber fossil assemblages across the Cenozoic. Biol Lett. 2006;2(2):266–270. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rust J, et al. Biogeographic and evolutionary implications of a diverse paleobiota in amber from the early Eocene of India. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(43):18360–18365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007407107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daza JD, Bauer AM, Wagner P, Böhme W. A reconsideration of Sphaerodactylus dommeli Böhme, 1984 (Squamata: Gekkota: Sphaerodactylidae), a Miocene lizard in amber. J Zoological Syst Evol Res. 2013;51(1):55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etheridge R, de Queiroz K. A phylogeny of Iguanidae. In: Estes R, Pregill G, editors. Phylogenetic Relationships of the Lizard Families. Stanford Univ Press; Stanford, CA: 1988. pp. 283–367. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger TJ, Mahler DL, Abzhanov A, Losos JB. Roles for modularity and constraint in the evolution of cranial diversity among Anolis lizards. Evolution. 2012;66(5):1525–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harmon LJ, Kolbe JJ, Cheverud JM, Losos JB. Convergence and the multidimensional niche. Evolution. 2005;59(2):409–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macey JR, Larson A, Ananjeva NB, Papenfuss TJ. Evolutionary shifts in three major structural features of the mitochondrial genome among iguanian lizards. J Mol Evol. 1997;44(6):660–674. doi: 10.1007/pl00006190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackman TR, Irschick DJ, de Queiroz K, Losos JB, Larson A. Molecular phylogenetic perspective on evolution of lizards of the Anolis grahami series. J Exp Zool. 2002;294(1):1–16. doi: 10.1002/jez.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackman TR, Larson A, de Queiroz K, Losos JB. Phylogenetic relationships and tempo of early diversification in Anolis lizards. Syst Biol. 1999;48(2):254–285. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Creer DA, de Queiroz K, Jackman TR, Losos JB, Larson A. Systematics of the Anolis roquet series of the southern Lesser Antilles. J Herpetol. 2001;35(3):428–441. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glor RE, Kolbe JJ, Powell R, Larson A, Losos J. Phylogenetic analysis of ecological and morphological diversification in Hispaniolan trunk-ground anoles (Anolis cybotes group) Evolution. 2003;57(10):2383–2397. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harmon LJ, Schulte JA, 2nd, Larson A, Losos JB. Tempo and mode of evolutionary radiation in iguanian lizards. Science. 2003;301(5635):961–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1084786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulte JA, Valladares JP, Larson A. Phylogenetic relationships within Iguanidae inferred using molecular and morphological data and a phylogenetic taxonomy of iguanian lizards. Herpetologica. 2003;59(3):399–419. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicholson KE, et al. Mainland colonization by island lizards. J Biogeogr. 2005;32(6):929–938. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicholson KE, Mijares-Urrutia A, Larson A. Molecular phylogenetics of the Anolis onca series: A case history in retrograde evolution revisited. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2006;306(5):450–459. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castiglia R, Annesi F, Bezerra A, Garcia A, Flores-Villela O. Cytotaxonomy and DNA taxonomy of lizards (Squamata, Sauria) from a tropical dry forest in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the coast of Jalisco, Mexico. Zootaxa. 2010;2508:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castañeda MdR, de Queiroz K. Phylogenetic relationships of the Dactyloa clade of Anolis lizards based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;61(3):784–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maddison DR, Maddison WP. 2001. MacClade: Analysis of Phylogeny and Character Evolution (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA)

- 48.Kumazawa Y, Nishida M. Sequence evolution of mitochondrial tRNA genes and deep-branch animal phylogenetics. J Mol Evol. 1993;37(4):380–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00178868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swofford DL. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and Other Methods) (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA)

- 50.Finden C, Gordon A. Obtaining common pruned trees. J Classif. 1985;2(1):255–276. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. 2007. Tracer v1.4. Available at tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/. Accessed July 8, 2015.

- 54.Brandley MC, Schmitz A, Reeder TW. Partitioned Bayesian analyses, partition choice, and the phylogenetic relationships of scincid lizards. Syst Biol. 2005;54(3):373–390. doi: 10.1080/10635150590946808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pyron RA, Burbrink FT, Wiens JJ. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13(1):93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahler DL, Revell LJ, Glor RE, Losos JB. Ecological opportunity and the rate of morphological evolution in the diversification of Greater Antillean anoles. Evolution. 2010;64(9):2731–2745. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.