Abstract

The trace fossil Trichichnus is proposed as an indicator of fossil bioelectric bacterial activity at the oxic–anoxic interface zone of marine sediments. This fulfils the idea that such processes, commonly found in the modern realm, should be also present in the geological past. Trichichnus is an exceptional trace fossil due to its very thin diameter (mostly less than 1 mm) and common pyritic filling. It is ubiquitous in some fine-grained sediments, where it has been interpreted as a burrow formed deeper than any other trace fossils, below the redox boundary. Trichichnus, formerly referred to as deeply burrowed invertebrates, has been found as remnant of a fossilized intrasediment bacterial mat that is pyritized. As visualized in 3-D by means of X-ray computed microtomography scanner, Trichichnus forms dense filamentous fabric, which reflects that it is produced by modern large, mat-forming, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria, belonging mostly to Thioploca-related taxa, which are able to house a complex bacterial consortium. Several stages of Trichichnus formation, including filamentous, bacterial mat and its pyritization, are proposed to explain an electron exchange between oxic and suboxic/anoxic layers in the sediment. Therefore, Trichichnus can be considered a fossilized “electric wire”.

1 Introduction

Bioelectric bacterial processes are omnipresent phenomena in the oxic–anoxic transition zone of recent marine sediments (see Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen, 2015, for review). It is intriguing that they have not so far been recognized from the geological past as it was suggested by Risgaard-Petersen et al. (2012). One reason could be that effects of such bacterial processes, leading to oxygenation of the anoxic sediments on the sea floor, are eventually destroyed by subsequent bioturbation (Malkin et al., 2014). We propose here that the usually pyritized marine trace fossil Trichichnus Frey (1970) can be interpreted as a fossil record of complex bioelectrical operations resulting from bacterial activities in the oxygen-depleted part of marine sediments. Trichichnus is a branched or unbranched, straight to winding, hair-like cylindrical structure, mostly 0.1–0.7 mm in diameter, commonly pyritized, oriented at various angles (mostly vertical) with respect to the bedding. The common pyritization is a particular feature of Trichichnus, which is generally absent in other trace fossils. Trichichnus is reported from both shallow- and deep-sea, mostly fine-grained sediments (Frey, 1970; Wetzel, 1983). It ranges from the Cambrian (Stachacz, 2012) to the Holocene (Wetzel, 1983). There are distinguished Trichichnus appendicus displaying thin appendages. T. linearis or T. simplex probably differs only in the presence of a lining, which likely is diagenetic in origin (see Uchman, 1999, for review). Trichichnus is common in sediments in which pore waters were poorly oxygenated (McBride and Picard, 1991; Uchman, 1995) and is considered to be one of the first trace fossils recording colonization of the sea floor after improvement of oxygenation, penetrating sediments below the redox boundary and having a connection to oxygenated waters on the sea floor (Uchman, 1995). It belongs to the ethological category chemichnia distinguished for trace fossils produced by organisms feeding by means of chemosymbiosis (Uchman, 1999).

Trichichnus was previously interpreted as a deep-tier burrow produced by unknown opportunistic invertebrates in poorly oxygenated sediments (McBride and Picard, 1991; Uchman, 1995). It has also been compared to an open burrow in modern deep-sea sediments more than 2 m long and no more than 0.5 mm thick (Thomson and Wilson, 1980; Weaver and Schultheiss, 1983). The sipunculid worm Golfingia has been considered as a possible modern example of trace makers of very narrow and long tubes similar to Trichichnus (Romero-Wetzel, 1987). However, 3-D microCT scanner images of Trichichnus presented in this paper reflect fabric produced by modern, large, sulfur bacteria. Therefore, a new interpretation of Trichichnus is possible by its comparison to modern sulfur bacteria such as Thioploca spp. and their postmortem history. Moreover, we propose a biogeochemical model of Trichichnus assisted electron transfer between different redox zones of the sediment.

2 Material and methods summary

The morphology and chemistry of Trichichnus from several samples, represented by Albian turbiditic marly mudstones (Silesian Nappe, Polish Carpathians); Valanginian–Hauterivian pelagic marlstones (Kościeliska Marl Formation, the Tatra Mountains) and Eocene silty shales (Magura Nappe, Polish Carpathians), were studied using a scanning electron microscope with field emission (FE-SEM, Hitachi S4700), equipped with EDS (Noran Vantage), which allows the determination of chemical compounds of the examined objects. The studies on morphology and infilling of Trichichnus were also supported using the polarizing light microscope Nikon Eclipse Pol E-600. All of the above were carried out at the Institute of Geological Sciences of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. Moreover, the X-ray computed microtomography (microCT) scanner (SkyScan 1173) available at the Institute of Palaeontology, University of Vienna, was used to carry out the main research on the spatial organization of the Trichichnus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Scanner setting data used for X-ray computed microtomography (microCT).

| Scanner | SkyScan 1173 |

|---|---|

| Camera pixel size | 50.0 μm |

| Source voltage | 130 kV |

| Source current | 61 μA |

| Camera binning | 1 × 1 |

| Filter | Al 1 mm |

| Exposure | 650 ms |

| Rotation step | 0.15° |

| Frame averaging | 30 |

| 360° rotation | on |

| Scan duration | 14 h 22 m |

| Pixel size | 9.97646 μm |

All samples of trace fossil Trichichnus presented in the paper are housed at the Institute of Geological Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland, collection of Alfred Uchman and Zbigniew Sawlowicz. No permits were required for the described study, which complied with all relevant regulations.

3 Results

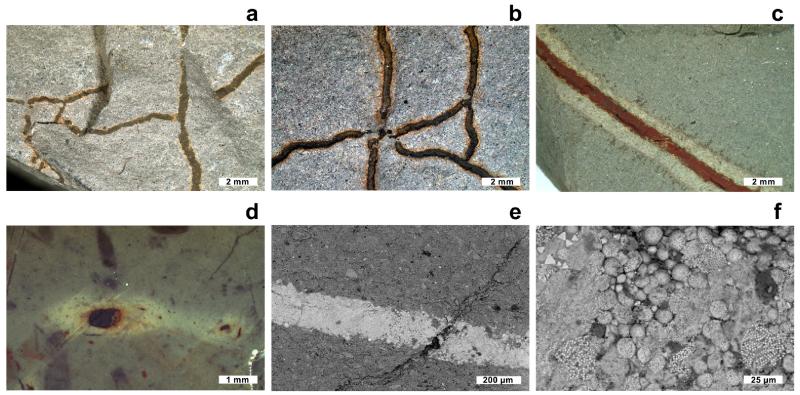

With the naked eye or under light microscope Trichichnus is easily distinguished in all rocks samples mainly by its different color (Fig. 1a–d). Macroscopically Trichichnus is similar in all samples and shows a light halo around the trace, except in burrows without iron mineral infillings (Fig. 1c and d). Neither the length nor width of the trace depends on the type of the host rock. The boundary between the trace fossil and the rock is usually sharp (Fig. 1e).

Figure 1.

Macro- and microimages of Trichichnus in the rock fractures and slabs: (a–c) Albian turbiditic marly mudstones, Kozy, Polish Carpathians; (d) Valanginian–Hauterivian pelagic marlstones. Dolina Kościeliska valley, Tatra Mountains, Poland (e), (f) Eocene silty shales, Zbludza, Polish Carpathians. (a)–(b) Subhorizontal network of Trichichnus. (c)–(d) Halo (diffusion zone of iron (oxi)hydroxides) around horizontal (c) and vertical (d) Trichichnus. (e) Infilling of a fragment of Trichichnus with abundant pyrite framboids and iron (oxi)hydroxides (SEM BSE). (f) Magnification of image (e). Specimen numbers: (a) INGUJ147P70, (b) INGUJ147P71, (c) INGUJ147P72, (d) INGUJ155P20, (e)–(f) INGUJ144P159.

The SEM studies revealed that majority of the studied Trichichnus is filled with framboids and framboidal aggregates (Fig. 1e and f). Framboidal forms are composed of iron sulfides (most probably pyrite), iron oxi/hydroxides or a mixture of both. The microcrystals building framboids are generally well-developed and their sizes are usually about 1–2 μm, generally dependent on the size of the framboid. Most of the microcrystals in framboids are closely packed. SEM-EDS study shows that the colorful halo around traces does not reveal any chemical differences from the composition of the surrounding rock. It is likely that the amount of iron minerals in the halo is below the detection limit of the EDS method. Apart from the iron minerals, subordinate amounts of several other minerals, generally corresponding to the host rock, such as calcite, quartz and gypsum, are observed.

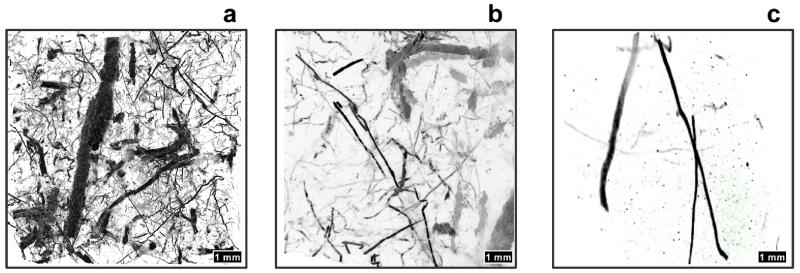

MicroCT scans allowed three-dimensional visualization of several Trichichnus embedded in a dark mudstone from the Oligocene Menilite Formation in the Western Carpathians, Poland. The density difference between the sediment matrix and the pyritic trace fossil fillings allowed extremely accurate three-dimensional visualization (Fig. 2). The results show a very dense fabric composed of Trichichnus fillings of variable size and orientation, which are only partly visible on a sample surface. Since the resolution of the 3-D model here presented is 9.97 μm, all the structures larger than 10 μm are visible and renderable. The distribution of diameters of the traces displays two major peaks: 600 μm for the thickest traces and 90 μm for the very thin ones (Fig. 2a; see also the Supplement).

Figure 2.

X-ray computed microtomography scanner images of different parts of Trichichnus spatial complex, Oligocene, Skole Nappe, Polish Flysch Carpathians: (a) Dense Trichichnus fabric, similar to the upper part of the Thioploca mat system. (b) Trichichnus fabric comparable with the middle part of the Thioploca mat system. (c) Trichichnus fabric depicting the lower part of the Thioploca mat system.

The Trichichnus morphology seen in 3-D microCT scanner image (Fig. 2a–c) is similar to structures produced by filamentous bacteria (e.g., Pfeffer et al., 2012) or to large, mat-forming, filamentous sulfur bacteria, e.g., Thioploca spp. (Fossing et al., 1995, their Fig. 3a; Schulz et al., 1996, their Fig. 8; Jørgensen and Gallardo, 1999, their Fig. 5; see also Heutell et al., 1996). The microCT scanner images also reveal different spatial organizations, density, diameters and shapes of the Trichichnus. These correspond to different parts of vertical system of the Thioploca mat in sediment. Also the density of Trichichnus (Fig. 2a), which constitutes 3.1 % of the whole scanned sediment volume, is comparable to the Thioploca mat in their upper shallow subsurface part. Other 3-D scanner images (Fig. 2b and c) show lowered density of Trichichnus, comparable to middle and bottom parts of the Thioploca filamentous mat spatial system.

4 Discussion

Three-dimensional reconstructions of Thioploca spp. (Fossing et al., 1995; Schulz et al., 1996; Jørgensen and Gallardo, 1999) resemble Trichichnus in the 3-D scanner images. Moreover, the common pyritization of Trichichnus is related to sulfate-reducing bacteria, like δ-proteobacteria Desulfovibrio spp., which can co-occur with sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, such as Beggiatoa or Thioploca (e.g., Jiang et al., 2012). Therefore, we consider Thioploca-like, mat-forming, large sulfur bacteria and related filamentous sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (see Teske et al., 1995) as a trace maker of Trichichnus tunnels and their spatial organization. The Thioploca-like mat, usually hosting other bacteria or small protists (e.g., Buck et al., 2014), combined with the postmortem history of sulfur bacterial mat systems, refer to the idea of bioelectrochemical systems (BESs), including microbial fuel cells (MFCs) and biogeobatteries (e.g., Naudet et al., 2003, 2004; Naudet and Revil, 2005; Linde and Revil, 2007; Ntarlagiannis et al., 2007; Logan, 2009; Teske et al., 2009; Nielsen and Girguis, 2010; Revil et al., 2010; Borole et al., 2011; Hubbard et al., 2011; Risgaard-Petersen et al., 2014; Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen, 2015, for review).

In biogeobattery systems, bacteria are interconnected cells to cells or cells to mineral surfaces via electrically conductive appendages – bacterial pili (nanowires) – making a complex electroactive network (biofilm) (Ntarlagiannis et al., 2007; Revil et al., 2010; Borole et al., 2011; Reguera et al., 2005; Gorby et al., 2006; El-Naggar et al., 2010; Nielsen et al., 2010; Risgaard-Petersen et al., 2014; Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen, 2015). The electron transport in BESs may be realized in various ways, including transfer through long bacterial nanowires or along biofilm matrix (Lovley, 2008). Its magnitude and duration mostly depend on atmospheric oxygen (electron acceptor) availability that generates electrical self-potentials in the sediments between oxidized and anoxic zones (see Ntarlagiannis, 2007; Risgaard-Petersen et al., 2014). Studies reporting extracellular bioelectric current concerned dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria, such as Geobacter sulfurreducens, Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and the thermophilic, fermentative bacterium Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum or the oxygenic phototrophic cyanobacterium Synechocystis (Borole et al., 2011). Natural conductive minerals (e.g., magnetite, greigite – an intermediate stage for pyrite formation) can facilitate electron transfer between different species of microbes. Presumably microbes should preferentially use mineral particles, discharging electrons to and accepting them from mineral surfaces, in particular for long-distance electron transfer (Kato et al., 2012). The interaction between minerals and bacteria can be quite complex as Kato et al. (2013) showed that, for example, G. sulfurreducens constructed two distinct types of extracellular electron transfer (EET) paths, in the presence and absence of iron-oxide minerals. It is worth noting that large-scale sulfide ores, where pyrite is commonly a main component, have been regarded as geobatteries for many years and used by geophysicists for exploration. In natural electrochemical processes an ore serves as a conductor to transfer the electrons from anoxic to oxic environments (Sato and Mooney, 1960; Naudet et al., 2003). Newer reports show that coupling of geochemical reactions between shallower and deeper layers of the sediment can be also realized by vertical centimeter-long filaments of multicellular bacteria of the family Desulfobulbaceae, the so-called cable bacteria (Pfeffer et al., 2012; Risgaard-Petersen et al., 2014; Schauer et al., 2014). Nevertheless, only giant sulfur bacteria, so-called “macro-bacteria”, are able to produce mat spatial system in the scale of Trichichnus. Macro-bacteria of Beggiatoacea family are considered to be the most direct competitors to cable bacteria at the interface of oxic–anoxic zone of marine sediments (see Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen, 2015). We propose Thioploca spp., one of the genus of Beggiatoacea family (see Salman et al., 2011), as a trace maker of Trichichnus.

Large communities of the sulfur bacteria Thioploca spp. produce the filaments consisting of thousands of cells that can penetrate 5–15 cm down into the sediment. These filaments (trichomes), bundled in common slime sheaths, make a dense bacterial mat, where the density decreases with depth leaving single sheaths in the deepest part of the spatial system of the mat. The Thioploca sheaths, rarely branched, extend in different directions, mostly vertically. One sheath can accommodate up to 100 filaments of 15–40 μm in diameter each, giving about 4 mm for the maximum diameter of the sheath (Fossing et al., 1995; Schulz et al., 1996). Thioploca trichomes gliding within sheaths can migrate through several redox horizons, coupling the reduction of nitrate in the overlying waters and the oxidation of dissolved sulfide in the sulfate reduction zone (Fossing et al., 1995; Heutell et al., 1996). Therefore, the sheaths are used as communication tubes and enable the sulfur bacteria to switch vertically between nitrate and sulfide (electron acceptor and donor, respectively). This sulfide oxidization mechanism leads to accumulation of elemental sulfur globules in the bacterial cells. Moreover, Thioploca trichomes may leave their sheaths and move into other sheaths; thus, one sheath can be occupied by different species (Jørgensen and Gallardo, 1999). Empty sheaths were found even at > 20 cm depth into the sediment. In contrast, the sheaths were not found shallower than a depth of a few centimeters in the sediments. Therefore, the surface and topmost part of the Thioploca mat system is formed by single bacterial filaments only (Schulz et al., 1996). However, brackish/freshwater T. ingrica may not form any mats at the sediment surface, showing biomass peaks 4–7 cm below the sediment surface (Høgslund et al., 2010).

The Thioploca sheaths – either filled with trichomes or abandoned – may be closely associated with other filamentous sulfate-reducing bacteria like Desulfonema spp. (Jørgensen and Gallardo, 1999; Teske et al., 2009). Thioploca spp. are known from both marine and lake environments. Nevertheless, their mass occurrences are related to high organic production and oxygen depletion, e.g., the Chile and Peru offshore upwelling system (Jørgensen and Gallardo, 1999).

Pyritized organic remains are common in the sedimentary record, and various mechanisms of fossil pyritization have been described (e.g., Canfield and Raiswell, 1991; Briggs et al., 1996). Apart from the similarity between the Trichichnus fabric and spatial organization of the Thioploca mat system, the common pyritization of Trichichnus also indicates its close relation to the sulfate-reducing bacteria. Schulz et al. (2000) observed that empty sheaths of Thioploca from the Bay of Conception during autumn/wintertime were stained with iron sulfides. As the most abundant metal sulfide in nature, pyrite FeS2 has a major influence on the biogeochemical cycles of sulfur and iron, and through its oxidation also of oxygen. There have been several important reviews on sedimentary pyrite formation (e.g., Berner, 1970; Schoonen, 2004; Rickard and Luther, 2007, and references therein), specifically on iron sulfide framboids (e.g., Love and Amstutz, 1966; Raiswell, 1982; Wilkin and Barnes, 1997; Sawłowicz, 2000; Ohfuji and Rickard, 2005, and references therein). It is important to stress that at low temperature pyrite growth is usually preceded by the formation of unstable iron monosulfides, such as mackinawite and greigite. The latter is the ferrimagnetic inverse thiospinel of iron. Pyrite, like other sulfide minerals, is a semiconductor determined to be “semi-metallic”, but its conductivity in different admixtures varies widely between 0.02 and 562 (Ωcm)−1 (Rimstidt and Vaughan, 2003, and references therein). Pyrite has a great potential in both interaction with microorganisms and electron transfer as its range of morphological, chemical and electric characteristics is quite large. Both iron and sulfur, necessary for pyrite formation, are pivotal for microbes. For instance, more than 50 % of reduced sulfate in sediments inhabited by Thioploca off the Chilean coast is accumulated in the pyrite pool (Ferdelman et al., 1997). Iron is an important carrier of electrons in microbial ecosystems (Wielenga et al., 2001), and bacteria play important role in different processes of iron oxidation and reduction (Weber et al., 2006). Interestingly, some Firmicutes bacteria species such as Desulfitobacterium frappieri are capable of both reducing Fe3+ with H2 as an electron donor and oxidizing Fe2+ with nitrate as an electron acceptor (Shelobolina, 2003). In sedimentary environments the major source of sulfur incorporated into iron sulfides is H2S or HS− resulting from bacterial sulfate reduction. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) use sulfate as the terminal electron acceptor of their electron transport chain (e.g., Widdel and Hansen, 1992). SRB are usually regarded as strictly anaerobic, but recent investigations showed that SRB are both abundant and active in the oxic zones of mats (see Baumgartner et al., 2006, for review). Iron monosulfides and pyrite, including framboids, are quite common in some microbial mats (e.g., Popa et al., 2004; Huerta-Diaz et al., 2012), but their formation is complicated and difficult to study. Nevertheless, sulfur content and sulfur speciation may not correlate with microbial metabolic processes (Engel et al., 2007). Oxidation of iron sulfides is one of the most common processes in marine sediments. For example, Passier et al. (1999) reported that in the Mediterranean sapropels the percentage of initially formed iron sulfides that were re-oxidized varied from 34 to 80 %. Oxidation of iron sulfide framboids to iron (hydro)oxides is often observed in fossils (e.g., Luther et al., 1982; Sawłowicz, 2000). There is a significant difference between oxidation of pyrite and its precursors. For example, FeS, but not pyrite, can be oxidized microbially with as an electron acceptor (Schippers and Jørgensen, 2002).

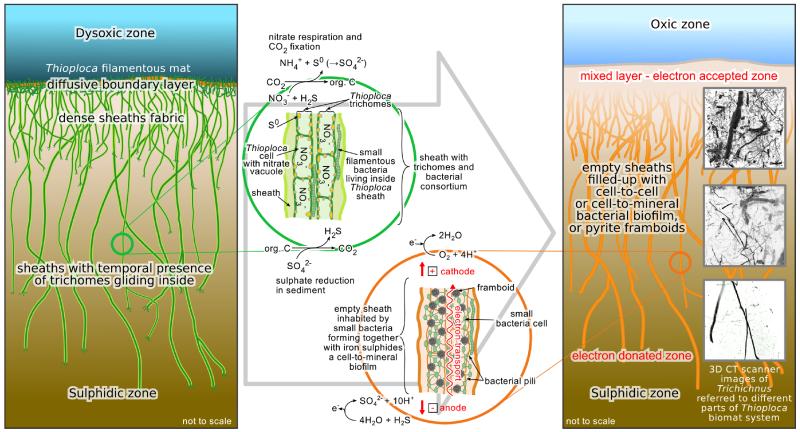

5 Conclusions and model of Trichichnus

Trichichnus is a good example of microbiological and mineralogical collaboration, propounded earlier by Naudet et al. (2003, 2004). Its role in electron transfer is still enigmatic, but several stages can be proposed (Fig. 3). It should also be noted that the relatively large length of Trichichnus and its continuation through different redox zones may result in its vertical internal zonation. As suggested earlier, Trichichnus may reflect former slime sheaths, where large sulfur bacterial trichomes, like Thioploca community, move up and down. There is growing evidence (e.g., Teske et al., 2009; Prokopenko et al., 2013; Buck et al., 2014, and references therein) that Thioploca sheaths house a complex bacterial consortium. In our opinion it is only a matter of time before additional microbes will be found associated with Thioploca or their postmortem sheaths.

The earliest stage of the Trichichnus formation is related to a sulfuric microbial mat in the dysoxic zone, connecting the anoxic–sulfidic substrate. Long, filamentous bacteria structured like electric cables facilitate electron transport over centimeter distances in marine sediment (Pfeffer et al., 2012; Risgaard-Petersen et al., 2014). The filamentous multicellular, aerobic bacteria of the family Desulfobulbaceae (cable bacteria), living together with Thioploca in the sheath, conduct electrons through internal insulated wires from cells in the sulfide oxidation zone to cells in the oxygen reduction zone (Pfeffer et al., 2012). For Thioploca itself such behavior has not been proven yet (see Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen, 2015, for review). The electric circuit is balanced by charge transport by ions in the surrounding environment (Risgaard-Petersen et al., 2014; Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen, 2015).

The next stage is related to the iron sulfidization process. Microorganisms can influence both the precipitation of sulfides and their morphology. Bacterial components (e.g., cell walls) facilitate mineralization by sequestration of metallic ions from solution and provide local sites for nucleation and growth (Beveridge and Fyfe, 1985). Iron sulfides (framboids) can form within a matrix of bacteria and biopolymers both during the life-time of bacterial consortium (see MacLean et al., 2008) and after their death. It should be noted that the process of sheath infilling varies within the system. For example, larger sheaths may be abandoned by trichomes of Thioploca faster, compared to smaller ones (Schulz et al., 1996). The biofilm in a proto-Trichichnus capsule seems to be an ideal place for the formation of iron sulfides. Formation of pyrite, probably formerly ferromagnetic greigite, depends on availability of soluble Fe(II) from a surrounding sediment and sulfides (H2S or polysulfides). Crystals in framboids are generally closely packed, and framboids themselves often too, but when it is not the case, the bacterial pili are believed to connect dispersed conductive minerals (Revil et al., 2010). Cell-to-mineral wires support the hypothesis that the metallic conductor-like pyrite occurring in sediment might be responsible for the electron flow (see also Nielsen et al., 2010). Growth of a biofilm – developed in the mucus of the large sulfur bacteria sheath – on pyrite can enhance conductivity supporting the biogeobattery idea. The oldest microbial communities colonizing sedimentary pyrite grains were found in a ~3.4-billion-year-old sandstone from Australia (Wacey et al., 2011).

The process of electron transfer can continue also after termination of microbial consortia. Decomposition of organic matter inside the channel creates the local reducing microenvironment, which promotes pyrite formation (e.g., Berner, 1980; Raiswell, 1982), even when the surrounding sediment is not fully anoxic. It is tempting to propose that perhaps some iron sulfide forms resulted from a replacement of sulfur globules (stored intra- and extracellularly by chemolithoautotrophic bacteria, e.g., Thioploca or by purple and green sulfur bacteria; Oschmann, 2000), either inside sulfur bacteria cells or after lysis. Spheroidal crystalline aggregates representing early pyrite and subsequently replaced by iron hydroxides were found in Silurian cyanobacterial filaments (Tomescu et al., 2006). Formation of pyrite framboids via replacement of sulfur grains was also shown experimentally by Křibek (1975). A halo observed around Trichichnus (Fig. 1c and d) results from oxidation of pyrite or former iron monosulfide infilling the trace fossil. The oxidation stage can take place both during the earliest and later stages of diagenesis (the latter is out of the scope of this paper). Re-oxidation processes of pyrite framboids are common in tropical upwelling area, caused by bioturbation and possible contributions from sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (Diaz et al., 2012, and references therein). It would additionally expand, but also complicate, the process of electron transfer in sediments.

Figure 3.

Model of the origin of Trichichnus. The ecology of Thioploca mat system and their sulfide oxidation chemistry (left). The Thioploca sheath system below the diffusive boundary layer forms a construction which may be inhabited by small bacteria making the conductive nanowire–pyrite framboid biofilm. This triggers the electric self-potential between the sulfidic zone and mixed layer, thus, the electron flow (right). The different part of the Trichichnus and the different part of the former Thioploca mat system are shown for comparison (right). Thioploca spp. nitrogen, carbon and sulfur metabolism reactions are taken from Teske and Nelson (2006); half-reactions on Trichichnus are adapted from Nielsen and Risgaard-Petersen (2015).

Summarizing, we believe that Trichichnus is a good example of a potential ancient place where several bioprocesses related to electron transfer in sediment could proceed. A large amount of evidence of such processes, both in the field and laboratory investigations, has been growing significantly for last few years. Development of new technologies, e.g., multipurpose electrodes which combine reactive measurements with electrical geophysical measurements (Zhang et al., 2010), opens new frontiers in monitoring microbial processes in sediments. We believe that our idea raises special attention to Thioploca endobionts with respect to their electron exchange along the cell-to-mineral wires. Our interpretation shows how this phenomenon could have been widespread in sedimentary environments and through the geological time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sally Sutton (Colorado State University) for her comments and suggestions, which improved the manuscript. We are indebted to the editor Jack Middelburg and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the manuscript. The use of MicroCT has been possible due to the project P 23459-B17 granted by the Austrian Science Fund. The work was supported by the Jagiellonian University in Kraków – DS funds project no. K/ZDS/004873.

Footnotes

The Supplement related to this article is available online at doi:10.5194/bg-12-2301-2015-supplement.

References

- Baumgartner LK, Reid RP, Dupraz C, Decho AW, Buckley DH, Spear JR, Przekop KM, Visscher PT. Sulphate reducing bacteria in microbial mats: changing paradigms, new discoveries. Sediment. Geol. 2006;185:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA. Sedimentary pyrite formation. Am. J. Sci. 1970;268:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA. Princeton Series in Geochemistry. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1980. Early diagenesis: a theoretical approach; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJ, Fyfe WS. Metal fixation by bacterial cell walls. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1985;22:1893–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Borole AP, Reguera G, Ringeisen B, Wang ZW, Feng Y, Kim BH. Electroactive biofilms: Current status and future research needs. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2011;4:4813–4834. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs DEG, Raiswell R, Bottrell SH, Hatfield D, Bartels C. Controls on the pyritization of exceptionally preserved fossils: an analysis of the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate of Germany. Am. J. Sci. 1996;296:633–663. [Google Scholar]

- Buck KR, Barry JP, Hallam SJ. Thioploca spp. sheaths as niches for bacterial and protistan assemblages. Mar. Ecol. 2014;35:395–400. doi:10.1111/maec.12076. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield DE, Raiswell R. Pyrite formation and fossil preservation. In: Allison PA, Briggs DEG, editors. Taphonomy: Releasing the Data Locked in the Fossil Record. Topics in Geobiology, 9, Plenum; New York: 1991. pp. 411–453. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R, Moreira M, Mendoza U, Machado W, Böttcher ME, Santos H, Belém A, Capilla R, Escher P, Albuquerque AL. Early diagenesis of sulfur in a tropical upwelling system, Cabo Frio, southeastern Brazil. Geology. 2012;40:879–882. [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar MY, Wanger G, Leung KM, Yuzvinsky TD, Southam G, Yang J, Lau WM, Nealson KH, Gorby YA. Electrical transport along bacterial nanowires from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18127–18131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004880107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AS, Lichtenberg H, Prange A, Hormes J. Speciation of sulfur from filamentous microbial mats from sulfidic cave springs using X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007;269:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdelman TG, Lee C, Pantoja S, Harder J, Bebout BM, Fossing H. Sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in a Thioploca-dominated sediment off the coast of Chile. Geochim. Cosmoch. Ac. 1997;61:3065–3079. [Google Scholar]

- Fossing H, Gallardo VA, Jørgensen BB, Huttel M, Nielsen LP, Schulz H, Canfield DE, Forster S, Glud RN, Gundersen JK, Kuver J, Ramsing NB, Teske A, Thamdrup B, Ulloa O. Concentration and transport of nitrate by the mat-forming sulphur bacterium Thioploca. Nature. 1995;374:713–715. [Google Scholar]

- Frey RW. Trace fossils of Fort Hays Limestone Member of Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous), West-Central Kansas, The University of Kansas. Paleontological Contributions. 1970;53:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gorby YA, Yanina S, McLean JS, Rosso KM, Moyles D, Dohnalkova A, Beveridge TJ, Chang IS, Kim BH, Kim KS, Culley DE, Reed SB, Romine MF, Saffarini DA, Hill EA, Shi L, Elias DA, Kennedy DW, Pinchuk G, Watanabe K, Ishii S, Logan B, Nealson KH, Fredrickson JK. Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11358–11363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604517103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heutell M, Forster S, Klöser S, Fossing H. Vertical migration in the sediment-dwelling sulphur bacteria Thioploca spp. in overcoming diffusion limitations. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1996;62:1863–1872. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høgslund S, Nielsen JL, Nielsen LP. Distribution, ecology and molecular identification of Thioploca from Danish brackish water sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010;73:110–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard CG, West LJ, Morris K, Kulessa B, Brookshaw D, Lloyd JR, Shaw S. In search of experimental evidence for the biogeobattery. J. Geophys. Res. 2011;116:G04018. doi:10.1029/2011JG001713. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Diaz MA, Delgadillo-Hinojosa F, Siqueiros-Valencia A, Valdivieso-Ojeda J, Reimer JJ, Segovia-Zavala JA. Millimeter-scale resolution of trace metal distributions in microbial mats from a hypersaline environment in Baja California, Mexico. Geobiology. 2012;10:531–47. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Cai CF, Zhang YD, Mao SY, Sun YG, Li KK, Xiang L, Zhang CM. Lipids of sulfate-reducing bacteria and sulfur-oxididzing bacteria found in the Dongsheng uranium deposit. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2012;57:1311–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen BB, Gallardo VA. Thioploca spp.: filamentous sulphur bacteria with nitrate vacuoles. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999;28:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen BB, Nelson DC. Sulphur biogeochemistry – past and present. Geol. S. Am. S. 2004;379:63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Hashimoto K, Watanabe K. Microbial interspecies electron transfer via electric currents through conductive minerals. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:10042–10046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117592109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Hashimoto K, Watanabe K. Iron-oxide minerals affect extracellular electron-transfer paths of Geobacter spp. Microbes Environment. 2013;28:141–148. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Křibek B. The origin of framboidal pyrite as a surface effect of sulphur grains. Miner. Deposita. 1975;10:389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Linde N, Revil A. Inverting self-potential data for redox potentials of contaminant plumes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007;34:L14302. doi:10.1029/2007GL030084. [Google Scholar]

- Logan BE. Exoelectrogenic bacteria that power microbial fuel cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:375–381. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love LG, Amstutz GC. Review of microscopic pyrite from the Devonian Chattanooga shale and Rammelsberg Banderz. Fortschr. Mineral. 1966;43:273–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lovley DR. The microbe electric: conversion of organic matter to electricity. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2008;19:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther GW, III, Giblin A, Howarth RW, Ryans RA. Pyrite and oxidized iron mineral phases formed from pyrite oxidation in salt marsh and estuarine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 1982;46:2665–2669. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean LCW, Tyliszczak T, Gilbert PUPA, Zhou D, Pray TJ, Onstott TC, Southam G. A high-resolution chemical and structural study of framboidal pyrite formed within a low-temperature bacterial biofilm. Geobiology. 2008;6:471–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2008.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin SY, Rao AMF, Seitaj D, Vasquez-Cardenas D, Zetsche E-M, Hidalgo-Martinez S, Boschker HTS, Meysman FJR. Natural occurrence of microbial sulphur oxidation by long-range electron transport in the seafloor. The ISME J. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride EF, Picard MD. Facies implications of Trichichnus and Chondrites in turbidites and hemipelagites, Marnosoarenacea Formation (Miocene), Northern Apennines, Italy. Palaios. 1991;6:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Naudet V, Revil A. A sandbox experiment to investigate bacteria-mediated redox processes on self-potential signals. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005;32:L11405. doi:10.1029/2005GL022735. [Google Scholar]

- Naudet V, Revil A, Bottero J-Y. Relationship between self-potential (SP) signals and redox conditions in contaminated groundwater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003;30:2091. doi:10.1029/2003GL018096. [Google Scholar]

- Naudet V, Revil A, Rizzo E, Bottero J-Y, Bégassat P. Groundwater redox conditions and conductivity in a contaminant plume from geoelectrical investigations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2004;8:8–22. doi:10.5194/hess-8-8-2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen ME, Girguis PR. Evidence for hydrothermal vents as “Biogeobatteries”, American Geophysical Union; Fall Meeting 2010; San Francisco, CA, USA. 2010; Abstract #NS33A-02. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen LP, Risgaard-Petersen N. Rethinking sediment biogeochemistry after the discovery of electric currents. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2015;7:21.1–21.18. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010814-015708. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-010814-015708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen LP, Risgaard-Petersen N, Fossing H, Christensen PB, Sayama M. Electric currents couple spatially separated biogeochemical processes in marine sediment. Nature. 2010;463:1071–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature08790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntarlagiannis D, Atekwana EA, Hill EA, Gorby Y. Microbial nanowires: Is the subsurface “hardwired”? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007;34:L17305. doi:10.1029/2007GL030426. [Google Scholar]

- Ohfuji H, Rickard DT. Experimental syntheses of framboids – a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2005;71:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Oschmann W. Microbes and black shales. In: Riding R, Awramik SM, editors. Microbial Sediments. Springer; Heidelberg: 2000. pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Passier HF, Middelburg JJ, De Lange GJ, Noettcher ME. Modes of sapropel formation in the eastern Mediterranean: some constraints based on pyrite properties. Mar. Geol. 1999;153:199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer C, Larsen S, Song J, Dong M, Besenbacher F, Meyer RL, Kjeldsen KU, Schreiber L, Gorby YA, El-Naggar MY, Leung KM, Schramm A, Risgaard-Petersen N, Nielsen P. Filamentous bacteria transport electrons over centimetre distances. Nature. 2012;491:218–221. doi: 10.1038/nature11586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa R, Kinkle BK, Badescu A. Pyrite framboids as biomarkers for iron-sulfur systems. Geomicrobiol. J. 2004;21:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Prokopenko MG, Hirst MB, De Brabandere L, Lawrence DJP, Berelson WM, Granger J, Chang BX, Dawson S, Crane EJ, III, Chong L, Thamdrup B, Townsend-Small A, Sigman DM. Nitrogen losses in anoxic marine sediments driven by Thioploca–anammox bacterial consortia. Nature. 2013;500:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiswell R. Pyrite texture, isotopic composition, and the availability of iron. Am. J. Sci. 1982;282:1244–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Mehta T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature. 2005;435:1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature03661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revil CA, Mendonça EA, Atekwana B, Kulessa SS, Hubbard KJ, Bohlen KJ. Understanding biogeobatteries: where geophysics meets microbiology. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo. 2010;115:G00G02. doi:10.1029/2009JG001065. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard D, Luther GW., III Chemistry of iron sulphides. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:514–562. doi: 10.1021/cr0503658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimstidt JD, Vaughan DJ. Pyrite oxidation: a state-of-the-art assessment of the reaction mechanism. Geochim. Cosmoch. Ac. 2003;67:873–880. [Google Scholar]

- Risgaard-Petersen N, Revil A, Meister P, Nielsen LP. Sulphur, iron-, and calcium cycling associated with natural electric currents running through marine sediment. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2012;92:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Risgaard-Petersen N, Damgaard LR, Revil A, Nielsen LP. Mapping electron sources and sinks in a marine biogeobattery. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo. 2014;119:1475–1486. doi:10.1002/2014JG002673. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Wetzel MB. Sipunculans as inhabitants of very deep, narrow burrows in deep-sea sediments. Mar. Biol. 1987;96:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Salman V, Amann R, Girnth A-C, Polerecky L, Bailey JV, Høgslund S, Jessen G, Pantoja S, Schulz-Vogt HN. A single-cell sequencing approach to the classification of large, vacuolated sulfur bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;34:243–259. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2011.02.001. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Mooney HM. The electromechanical mechanism of sulphide self-potentials. Geophysics. 1960;25:226–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sawłowicz Z. Framboids: from their origin to application. Prace Mineralogiczne, Polish Academy of Science, Div. Kraków. 2000;88:1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer R, Risgaard-Petersen N, Kjeldsen KU, Tataru Bjerg JJ, Jørgensen BB, Schramm A, Nielsen LP. Succession of cable bacteria and electric currents in marine sediment. The ISME J. 2014;8:1314–1322. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.239. doi:10.1038/ismej.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schippers A, Jørgensen BB. Biogeochemistry of pyrite and iron sulfide oxidation in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2002;66:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonen MAA. Mechanisms of sedimentary pyrite formation. Geol. S. Am. S. 2004;379:117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz HN, Jørgensen BB, Fossing HA, Ramsing NB. Community structure of filamentous, sheath-building sulphur bacteria, Thioploca spp., off the coast of Chile. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1996;62:1855–1862. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.1855-1862.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz HN, Strotmann B, Gallardo VA, Jorgensen BB. Population study of the filamentous sulfur bacteria Thioploca spp. off the Bay of Concepcion, Chile. Marine Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2000;200:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Shelobolina ES, Gaw Van Praagh C, Lovley DR. Use of ferric and ferrous iron containing minerals for respiration by Desulfitobacterium frappieri. Geomicrobiol. J. 2003;20:143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Stachacz M. Ichnology of Czarna Shale Formation (Cambrian, Holy Cross Mountain, Poland) Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 2012;82:105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Teske A, Nelson DC. The genera Beggiatoa and Thioploca. Prokaryotes. 2006;6:784–810. [Google Scholar]

- Teske A, Ramsing NB, Küver J, Fossing H. Phylogeny of Thioploca and related filamentous sulfide-oxidizing bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1995;18:517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Teske A, Jørgensen BB, Gallardo VA. Filamentous bacteria inhabiting the sheaths of marine Thioploca spp. on the Chilean continental shelf. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;68:164–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J, Wilson TRS. Burrow-like structures at depth in a Cape Basin red clay core. Deep-Sea Res. 1980;27A:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tomescu AMF, Rothwell GW, Honegger R. Cyanobacterial macrophytes in an Early Silurian (Llandovery) continental biota: Passage Creek, lower Massanutten Sandstone, Virginia, USA. Lethaia. 2006;39:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Uchman A. Taxonomy and palaeoecology of flysch trace fossils: the Marnoso-arenacea Formation and associated facies (Miocene, Northern Apennines, Italy) Beringeria. 1995;15:3–115. [Google Scholar]

- Uchman A. Ichnology of the Rhenodanubian Flysch (Lower Cretaceous-Eocene) in Austria and Germany. Beringeria. 1999;25:65–171. [Google Scholar]

- Wacey D, Saunders M, Brasier MD, Kilburn MR. Earliest microbially mediated pyrite oxidation in ~3.4 billion-year-old sediments. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2011;301:393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver PPE, Schultheiss PJ. Vertical open burrows in deep-sea sediments 2 m in length. Nature. 1983;301:329–331. [Google Scholar]

- Weber KA, Achenbach LA, Coates JD. Microorganisms pumping iron: Anaerobic microbial iron oxidation and reduction. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:752–764. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel A. Biogenic structures in modern slope to deep-sea sediments in the Sulu Sea Basin (Philippines) Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 1983;42:285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Widdel F, Hansen TA. The prokaryotes. In: Balows A, Truper HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer KH, editors. Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria: Ecophysiology, Isolation, Identification, Applications. Vol. 1. Springer; New York: 1992. pp. 582–624. [Google Scholar]

- Wielinga B, Mizuba MM, Hansel CM, Fendorf S. Iron promoted reduction of chromate by dissimilatory iron-reducing bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:522–527. doi: 10.1021/es001457b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin RT, Barnes HL. Formation processes of framboidal pyrite. Geochim. Cosmoch. Ac. 1997;61:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Ntarlagiannis D, Slater L, Doherty R. Monitoring microbial sulfate reduction in porous media using multi-purpose electrodes. J. Geophys. Res. 2010;115:G00G09. doi:10.1029/2009JG001157. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.