Abstract

Background & Aims

The prevalence of obesity continues to rise in both developed and developing nations. An association between iron status and obesity has been described in children and adults. We aimed to study the relation between serum hepcidin level and both iron as well as high sensitive CRP status in obese adolescents.

Materials & Methods

This work was conducted on 80 adolescents aging 12–14 years old, divided into two equal groups; obese and non-obese. Anthropometric measurements, determination of haemoglobin, serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), transferrin saturation, serum ferritin, soluble serum transferrin receptor (sTfR), high sensitive CRP (hs –CRP) and serum hepcidin were performed.

Results

Obese adolescents showed significantly lower levels of haemoglobin, serum iron, serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Significant higher diastolic blood pressure, higher mean TIBC, sTfR, serum hepcidin and hs –CRP were also found. Serum hepcidin level correlated positively with BMI and hs- CRP, but negatively with iron level in obese group.

Conclusion

These data suggest that hepcidin is an important modulator of anemia in obese patients. Obesity can be considered as a low grade inflammatory state, that stimulates the production of inflammatory markers such as CRP which can up-regulate hepcidin synthesis.

Keywords: Obesity, Hepcidin, Iron deficiency, Children

Introduction

Obesity is increasing rapidly all over the world not only in adults but also among children. (1) The World Health Organization (WHO) described obesity as a chronic disease and one of the most important public health threats. This is because of the relationships between obesity and chronic conditions later, for example, hypertension and cardiac and metabolic diseases.(2)

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is the main micronutrient deficiency that may affect adolescent. It is one of the most universally prevalent diseases in the world today particularly developing countries and it is a major public health. Iron deficiency has been considered an important risk factor for ill health and is estimated to affect 2 billion people worldwide. (3)

Adipose tissue is now recognized as an endocrine organ that can contribute to the inflammatory process by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines, also named adipokines, and the resulted inflammatory state may have an important pathogenic role in some obesity-relatedco morbidities.(4)

The identification of hepcidin, a 25-aminoacid peptide produced prevalently in the liver, opened a new era in understanding iron metabolism.(5) Hepcidin represents the main regulator of intestinal iron absorption and macrophage iron release and, thus, ultimately of the iron available for erythropoiesis. (6) Hepcidin is also known to be increased in humans in generalized inflammatory disorders, causing anemia of chronic diseases. (7) Evidence, in fact, has been provided for a tight direct correlation between hepcidin expression and some cytokines such as IL-6 and C-reactive protein that are increased in obesity. (8) (9) To strengthen the possible link between the poor iron status of obesity and hepcidin, there is the interesting observation that hepcidin is expressed not only in the liver but also in adipose tissue and that m RNA expression is increased in adipose tissue of obese patients. (10)

This study aimed to study the relation between serum hepcidin level and iron status in obese adolescents. It also aimed to study its relation with the inflammatory state as indicated by hs- CRP.

Materials & Methods

Study design and subjects

This is a case-control study. Iron status as well as haemoglobin, high sensitive C-reactive protein (hs – CRP), hepcidin, levels have been measured in 2 groups of 40 obese children who have attended the nutrition clinic at the National Research Center and in 40 sex- and age-matched lean controls who consulted the pediatric clinic in the National Research centre for minor complaints.

Anthropometric measures

Weight and height of all the subjects involved in the research were measured, and BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (wt (kg)/Ht (m2)). BMI exceeding the 95th percentile was used for obesity diagnosis. Controls had BMI below the 85th percentile.(11) Pubertal status was evaluated according to the criteria of Tanner. (12)

Blood sampling& serum preparation

Blood samples were obtained by aseptic technique using vein puncture. About 5 cc venous blood were withdrawn from each child after overnight fasting (about 8 hrs) and divided into 2 parts. The first part was about 1 cc whole blood was collected on EDTA plastic tubes serving as anticoagulant (Ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid) for Haemoglobin (HB) assay. Samples for haemoglobin were subjected for immediate assay (within 6 hrs). The second part was collected in plain plastic clean tubes without additives for serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC) serum ferritin, soluble serum transferrin receptor (sTfR), high sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and serum hepcidin. It was kept at room temperature for 2 hours, where it was allowed to clot, after which they were centrifuged and the serum was separated and kept in plastic Eppendorf tubes then frozen at −20°C till the time of assay. Blood samples for haemoglobin, serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC) serum ferritin, soluble serum transferrin receptor (sTfR), high sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and serum hepcidin (HB) were obtained after overnight fasting (about 8 hrs). Anaemia in school children was defined according to WHO standards, as Hb< 11.5 g/dl and severe anaemia as < 7.0 g/dl. (13)

Measurement of serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), transferrin saturation, serum ferritin, soluble serum transferrin receptor (sTfR), high sensitive CRP (hs –CRP) and serum hepcidin

Iron status has been assessed by serum iron, (14) transferrin, and ferritin concentrations. (15) Transferrin saturation has been calculated. Transferrin saturation was calculated by finding the molar ratio of serum iron and twice the serum transferrin (because each transferrin molecule can bind two atoms of iron) using the formula: transferrin saturation = [serum iron (micrograms per deciliter)/transferrin(milligrams per deciliter)] × 71.2. (16)

High sensitive CRP (hs-CRP) values were classified by American Heart Association (AHA) standards for risk for cardiovascular disease: Low (<1 mg/L), Intermediate (1–3 mg/L), or High (>3 mg/L). (17) Serum hepcidin was measured, reference value for this age group of children 0.312 – 20ng/ml.(5)

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done using SPSS version 16. Simple statistics and bivariate analysis were used. For comparing between two means, Student t-test of significance was done while one way analysis of variance was used to compare between more than two means. The Chi-square test of significance was used to compare frequency between two categorical variables. Correlation analysis using Pearson test was performed between different quantitative variables. In case of P value less than 0.05 the difference between two observations is considered statistically significant. Odds ratio was used to measure the magnitude of the risk factors related to obesity.

Results

1. Comparison between obese cases and controls as regards anthropometric data

The present study included 40 adolescents suffering from simple obesity (21 females and 19 males) their ages range from 12–14 years old, mean BMI was 33kg/m2 with BMI SDS ±3.1 presented to the Nutrition clinic at the National Research Center, they were selected according to BMI equal to or exceeding the 95th percentile for age and sex and 40 non-obese age and sex matched adolescents attending the pediatric clinic in the National Research Centre for minor complaints were taken as the control group, their BMI were 5th – 84th percentile for age and sex using the Egyptian Growth Charts. (11)

A highly statistically significant increased weight, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference and waist to hip ratio were found in cases when compared to control group (Table 1).

Table (1).

Comparison between cases and controls as regards anthropometric data

| Cases (obese) (n= 40) | Control (non-obese) (n= 40) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Weight (kg) | 81.3 ± 5.4 | 54.3 ± 7.0 | 0.001** |

| Height (cm) | 154.1 ± 9.3 | 153.1 ± 3.8 | 0.503 |

| BMI (kg/Ht2) | 33.0 ± 3.1 | 21.3 ± 1.0 | 0.001** |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 99.4 ± 10.6 | 58.9 ± 1.5 | 0.001** |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 60.1 ± 5.8 | 44.7 ± 1.2 | 0.001** |

| Waist:hip(cm) | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 0.001** |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD

‘t’= t test

HS= P<0.01= highly significant.

P> 0.05= not significant.

2. Comparison between obese cases and controls as regards serum hepcidin level and hs-CRP

Results of the present study showed that obese adolescents when compared to the control group had highly statistically significant increased mean hs- CRP 9.3±4.3 vs 3.3±2.4 (μg/dl) as well as significant increased mean serum hepcidin 3.1±3.6 vs 1.4±1.0 (ng/ml) (Table 2 ).

Table (2).

Comparison between cases and controls as regards serum hepcidin level and hs-CRP

| Cases (obese) (n= 40) | Control(non-obese) (n= 40) | ‘t’ test | p value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hepcidin(ng/ml) | 3.1 ± 3.6 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | −2.766 | 0.008** | HS |

| Hs-CRP (μg/dl) | 9.3 ± 4.3 | 3.3 ± 2.4 | −7.887 | 0.001** | HS |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

‘t’= t test

HS= P<0.01= highly significant.

hs-CRP = high sensitive c reactive protein

3. Correlations between serum hepcidin level and BM, hs-CRP, serum iron in obese adolescents

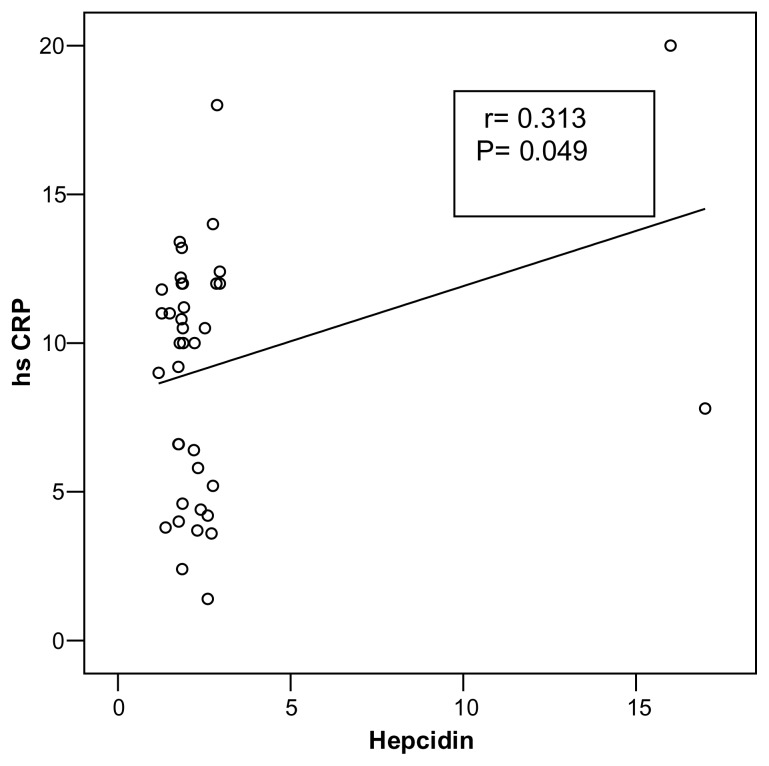

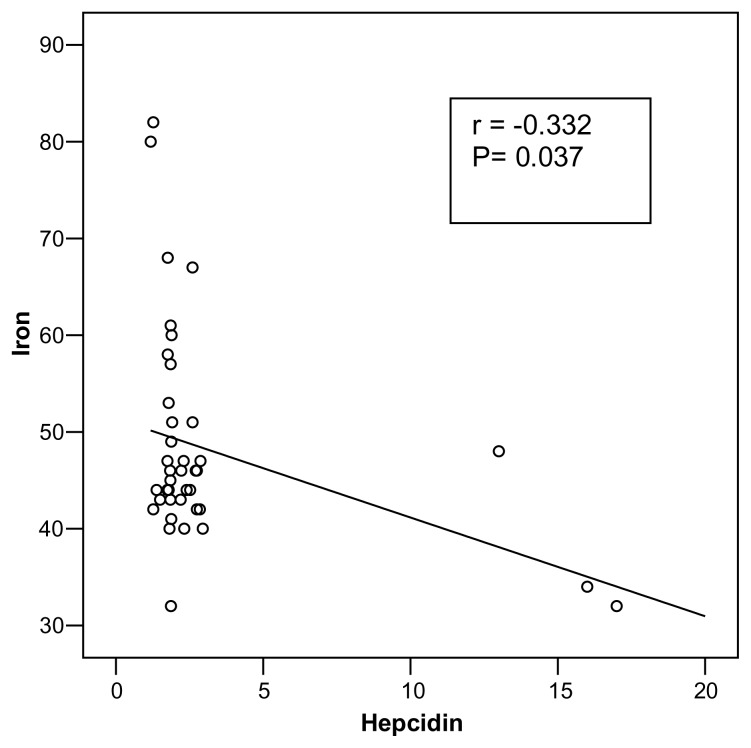

A direct correlation between serum hepcidin and both BMI(r= 0.550; P= 0.001) was observed (Fig. 1) as well as hs-CRP (r= 0.313; p= 0.049) (Fig. 2) where as a statistically significant negative correlation between serum hepcidin and serum iron(r= −0.332; P= 0.037) were observed among obese adolescents (Fig 3).

Figure (1).

Correlation between serum hepcidin level and BMI in obese adolescents

Figure (2).

Correlation between serum hepcidin level and hs -CRP in obese adolescents

Figure (3).

Correlation between serum hepcidin level and serum iron in obese adolescents

Discussion

Obesity in children is a complex disorder. Its prevalence has increased so significantly in recent years that many consider it a major health concern of the developed world. In addition, obesity is now considered a low-grade inflammatory disease since adipose tissue in obese individuals secretes a variety of pro inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 and hs-CRP. (18) In this regard, the present study showed that obese adolescents had highly statistically significant increase in the mean level of hs-CRP, as compared to their control counterpart. This result is in agreement with that obtained by Richardson et al. (19) The previous authors postulated that early obesity is associated with different grades of inflammation.

Iron deficiency has been considered an important risk factor for ill health. (3) The most prevalent and preventable form of microcytic anaemia is iron deficiency anaemia which is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide. Also, it had been reported that obese children were considered a high-risk group for iron deficiency (ID) from a public health perspective. The results of our study showed a significant feature of iron deficiency anemia among obese subjects as compared to the control adolescence. (20)

Hepcidin, a circulating antimicrobial peptide hormone synthesized in the liver, is the principal regulator of systemic iron homeostasis. Hepcidin controls plasma iron concentration and tissue distribution of iron by inhibiting intestinal iron absorption, iron recycling by macrophages, and iron mobilization from hepatic stores. (21) The present study revealed a significant increase in the plasma level of hepcidin in obese adolescence as compared to their control counter parts. Our result is in agreement with the results that obtained by, Bekri et al., (10) Richardson et al., (19) Sanad Mohammed et al.,(22 ) and Aeberli et al. (23) In this regard, Bekri et al., (10) postulated that hepcidin RNA expression as well as its protein levels were increased in adipose tissue of obese patients. In vitro, it had been reported that serum Hepcidin levels, IL-6, serum ferritin and plasma leptin were significantly high in obese group; also there was significant decrease in serum iron, TIBC and transferrin saturation (TS)% in obese group compared with the non-obese group. Also a direct correlation between Hepcidin, and Leptin and IL-6 was observed. Furthermore, there were significant inverse correlations between serum hepcidin and serum iron and TS% and between ferritin and TS%. (24)

It has been reported that higher level of hepcidin in overweight children may be due to obesity-related inflammation, evidenced by three inflammatory markers, CRP, IL-6 and leptin which were increased in the overweight children. (23) Indeed, the results of the present study showed a significant increase in the mean plasma levels of hs-CRP as compared to its levels in non-obese adolescence. The latter observation may confirm a state of systemic inflammation in our obese adolescents.

The present study showed a high statistically significant positive correlation between hepcidin and BMI(r= 0.550 P= <0.001) in obese adolescents. Similarly, Aeberli et al., (23) and Del Giudice et al., (25) found a direct correlation between serum hepcidin and BMI. Also, the present study showed a statistically significant positive correlation between serum hepcidin and hs-CRP (r= 0.313; P= 0.049) and a statistically significant negative correlation between serum hepcidin and serum iron (r= −0.332; P= 0.037) in obese group. Our results are in agreement with Del Giudice et al., (25) who reported a significant inverse correlation between serumhepcidin and serum iron.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that iron deficiency in obese adolescents could be the result of disrupted iron metabolism due to hepcidin-mediated reduced iron absorption and/or an increased iron sequestration.

Recommendations

Screening for iron deficiency anaemia should be done at regular intervals among obese children and adolescents for designing and implementing tailored- made dietary intervention approaches to correct both excess body weight and poor iron status.

Weight loss programs for obese children and adolescents may be essential for correction of iron status by decreasing serum hepcidin level.

Intervention studies in overweight children and adolescents should be done to assess the effect of weight loss on circulating hepcidin, iron absorption and iron status.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide Trends in Childhood Overweight and Obesity. Int J PediatrObes. 2006;1:11–25. doi: 10.1080/17477160600586747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO (World Health Organization) Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Expert Committee on Physical Status World Health Organization; Geneva: 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO (World Health Organization) A guide for programme managers. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. Iron Deficiency Anaemia: assessment, prevention, and control. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan C. Epidemic inflammation: pondering obesity. Mol Med. 2008;1:485–492. doi: 10.2119/2008-00038.Nathan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause A, Nietz S, Magert HJ, Schulz A, Forssmann WG, Schulz-Knappe P, et al. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett. 2000;480:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01920-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camaschella C, Silvestri L. New and old players in the hepcidin pathway. Haematologica. 2008;93:1441–1444. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein D, Roy C, Fleming M, Loda M, Wolfsdorf J, Andrews NC. Inappropriate expression of hepcidin is associated with iron refractory anemia: implications for the anemia of chronic disease. Blood. 2002;100:3776–3781. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, Keller C, Taudorf S, Pedersen BK, et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1271–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman A, Aigner E, Weghuber D, Paulmichl K. The Potential Role of Iron and Copper in Pediatric Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Bio Med ResInter. 2015:2–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/287401. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekri S, Gual P, Anty R, Luciani N, Dahman M, Ramesh B, et al. Increased adipose tissue expression of hepcidin in severe obesity is independent from diabetes and NASH. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:788–796. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghalli I, Salah N, Hussien F, Erfan M, El-Ruby M, Mazen I, et al. Egyptian growth curves for infants, children and adolescents. In: Satorio A, Buckler JMH, Marazzi N, editors. Crecerenelmondo. Ferring Publisher; Italy: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanner JM. Education and physical Growth: Implications of the study of children’s Growth for educational theory and practice. 4th edition. Blackwell; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoltzfus RJ, Dreyfuss ML. Guidelines for the Use of Iron Supplements to Prevent and Treat Iron Deficiency Anemia. Inter NutrAnaemia Consultative group/WHO/UNICEF; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burtis CA, Edward A. Tietz Text book of Clinical Chemistry. 2nd edition. W.B. Saunders Company; 1994. p. 2195. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burtis CA. Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry. 3rd edition. W.B. Saunders Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dallman PR. Iron deficiency and related nutritional anemias. In: Nathan DG, Orkin SH, editors. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology of infancy and childhood. WB Saunder’s; Philadelphia: 1987. pp. 274–314. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeh ET. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein as a risk assessment tool for cardiovascular disease. Clinical Cardiology. 2005;28(9):408–412. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960280905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClung JP, Karl JP. Iron deficiency and obesity: the contribution of inflammation and diminished iron absorption. Nutrition Reviews. 2009;67(2):100–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson MW, Ang L, Visintainer PF, Wittcopp CA. The abnormal measures of iron homeostasis in pediatric obesity are associated with the inflammation of obesity. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2009;713269 doi: 10.1155/2009/713269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee GR. Stages of development, prevalence, etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and definition of iron deficiency anemia. In: Lee GR, Foerester J, Lukens J, Paraskevas F, Geer JP, Roadgers GM, editors. Wintrobe’s Clinical hematology. 10th edition. Williams and Wilkins; 1999. p. 981. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumgartner J, Smuts CM, Aeberli I, Malan L, Tjalsma H, Zimmermann MB. Overweight impairs efficacy of iron supplementation in iron-deficient South African children: a randomized controlled intervention. Int J Obes. 2013;37(1):24–30. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammed Sanad, Mohammed Osman, Amal Gharib. Obesity modulate serum hepcidin and treatment outcome of iron deficiency anemia in children: A case control study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;37:34. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-37-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aeberli I, Hurrell RF, Zimmermann MB. Overweight children have higher circulating hepcidin concentrations and lower iron status but have dietary iron intakes and bioavailability comparable with normal weight children. Int J Obes. 2009;33:1111–1117. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abo Zeid AA, El Saka MH, Abdalfattah AA, Zineldeen DH. Potential factors contributing to poor iron status with obesity. Alex J Med. 2014;50:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Giudice EM, Santoro N, Amato A, Brienza C, Calabrò P, Wiegerinck ET, et al. Hepcidin in obese children as a potential mediator of the association between obesity and iron deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:5102–5127. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]