Abstract

Cohort analysis has been the cornerstone of tuberculosis (TB) monitoring and evaluation for nearly two decades; these principles have been adapted for patients with the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune-deficiency syndrome on antiretroviral treatment and patients with diabetes mellitus and hypertension. We now make the case for using cohort analyses for monitoring pregnant women during antenatal care, up to and including childbirth. We believe that this approach would strengthen the current monitoring and evaluation systems used in antenatal care by providing more precise information at regular time intervals. Accurate real-time data on how many pregnant women are enrolled in antenatal care, their characteristics, the interventions they are receiving and the outcomes for mother and child should provide a solid basis for action to reduce maternal mortality.

Keywords: cohort analysis, pregnant women, antenatal care

Abstract

Une analyse de cohorte a été la pierre angulaire du suivi et évaluation de la tuberculose pendant près de deux décennies ; ces principes ont été adaptés aux patients atteints de virus de l'immunodéficience humaine/syndrome de l'immunodéficience acquise sous traitement antiretroviral, ainsi qu'aux patients ayant un diabète et une hypertension. Nous recommandons maintenant l'utilisation d'analyse de cohorte pour le suivi des femmes enceintes en consultation prénatale et jusqu'à l'accouchement inclus. Nous pensons que cette approche renforcerait le système actuel de suivi et évaluation utilisé en consultation prénatale en fournissant des informations plus précises à intervalles réguliers. Des données exactes en temps réel sur le nombre de femmes enceintes enrôlées en consultation prénatale, leurs caractéristiques, l'intervention mise en place et les résultats vis-à-vis de la mère et de l'enfant, devraient fournir une solide base d'action visant à diminuer la mortalité maternelle.

Abstract

El análisis de cohortes ha constituido la piedra angular del seguimiento y de la evaluación de la tuberculosis durante cerca de dos decenios; estos principios se adaptaron a los pacientes coinfectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana y la síndrome de la inmunodeficiencia adquirida que reciben tratamiento antirretrovírico y a los pacientes con diabetes e hipertensión. En el presente artículo se defiende la oportunidad de utilizar los análisis de cohortes en el seguimiento de las embarazadas durante el cuidado prenatal, hasta incluir el nacimiento. Se propone que esta estrategia reforzaría los sistemas de seguimiento y evaluación que se practican actualmente en la atención prenatal, pues aportaría información más precisa y a intervalos regulares. Obtener los datos exactos y en tiempo real sobre la forma como las embarazadas se inscriben a la atención prenatal, sus características, las principales intervenciones que reciben y los desenlaces de la madre y el niño aportaría fundamentos sólidos a las actividades encaminadas a disminuir la mortalidad materna.

Cohort analysis of tuberculosis (TB) patients registered for treatment and their subsequent treatment outcomes has been the cornerstone of TB monitoring and evaluation for nearly two decades.1 Such cohort analyses answer two fundamental questions: how many patients have been diagnosed with TB, and what happens to them.2 Cohort analyses at health facility level and then national level, with reports sent to and collated by the World Health Organization (WHO), have formed the basis of the WHO annual global reports on TB control that have been so valuable in informing the world about progress made and outstanding challenges remaining.3

This cohort monitoring system has been successfully adapted and used in low- and middle-income countries to monitor care and health service delivery for other, more chronic diseases, such as antiretroviral treatment (ART) for people living with the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and the treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension.4–7 We also believe that the routine monitoring and evaluation systems currently in use for maternal and antenatal care could be improved by using a cohort analysis approach.

MATERNAL AND ANTENATAL CARE

In the last two decades, progress has been made in reducing global maternal mortality, but in 2010 an estimated 287 000 women nevertheless died, with the majority of these deaths disproportionally affecting families in low- and middle-income countries.8 Women in sub-Saharan Africa fare particularly badly, and maternal mortality remains high in most African countries, with deaths occurring as a result of obstetric complications such as haemorrhage, infections and hypertensive disorders, previous existing disease or disease that developed during pregnancy.9 Reducing maternal mortality requires much better access to emergency obstetric care services, but the quality and availability of care varies considerably from one health facility to another.10

At clinic level, therefore, accurate, real-time data on how many pregnant women are enrolling in antenatal care (ANC), the interventions they are receiving and the outcomes for mother and child provide a solid basis for action to monitor and improve the standard of care and thereby maternal health.

COHORT ANALYSES FOR MONITORING AND REPORTING ON ROUTINE ANTENATAL CARE

The cohort analysis method would be a useful approach for managing pregnant women during ANC, up to and including childbirth, and we believe that this would strengthen the current monitoring and evaluation systems by providing more precise information at regular time intervals. The monthly or quarterly ANC cohort would be defined as all women who registered in the antenatal clinic in that month (e.g., January) or that quarter (e.g., between 1 January and 31 March), regardless of age, duration of pregnancy, parity and past obstetric history. The characteristics of these women, included as data variables in the ANC treatment cards, registers and reports, could be adapted to the needs of any given facility, depending on the types of prevalent disease that affect pregnant women in that country. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, data on HIV status and ART would be important information to collect, while in other countries without a generalised HIV epidemic, data on DM and hypertension might be more important.

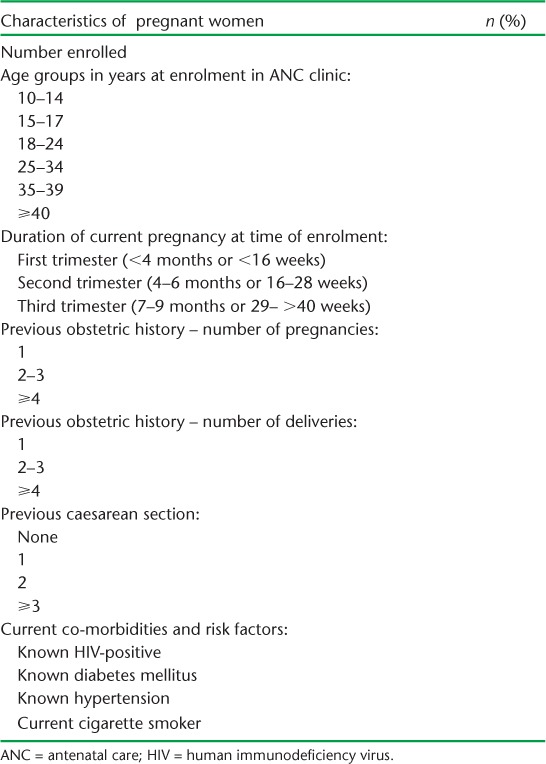

Some of the parameters that might be included are shown in Table 1. These consecutively reported monthly or quarterly cohorts of enrolled pregnant women would provide valuable information about new incident pregnancies, with the women stratified by age, time of presentation during pregnancy, co-morbid conditions and relevant past obstetric histories. These data can be compared between successive cohorts presenting for care, allowing health care providers to assess trends over time, whether access to health care services are improving, whether women are presenting earlier in their pregnancies and whether co-morbid conditions and risk factors are changing.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women enrolled in a quarterly cohort

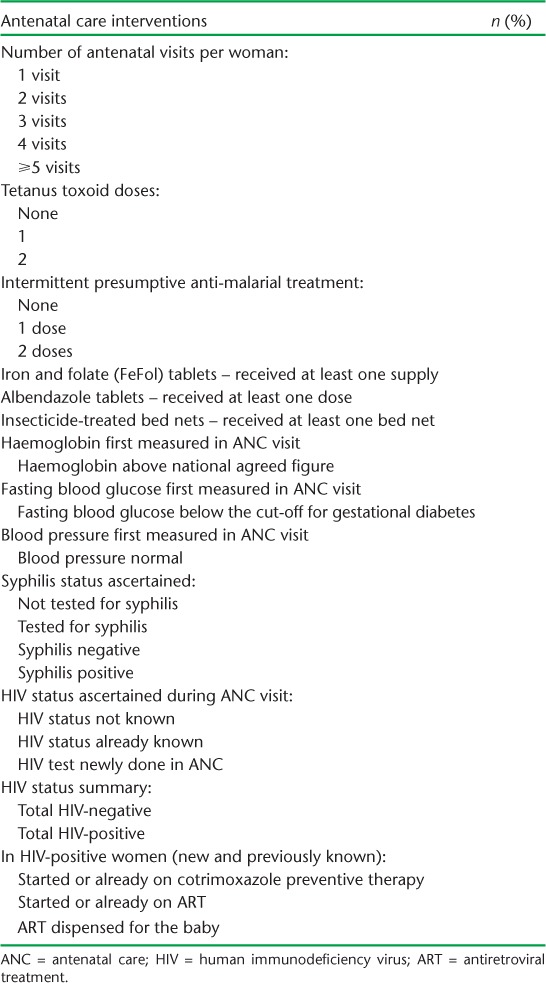

The ANC received and the outcomes of this registration cohort of pregnant women need to be analysed and aggregated 6–9 months later, depending on the earliest expected gestational age at enrolment in the respective setting. This is determined by the maximum interval between the first and last ANC visit. Data analysis should be carried out in two stages. The first stage is across all visits for each woman, to summarise all relevant conditions and interventions received in a ‘final status’. The second stage involves aggregation of the final status data for all women in the respective registration cohort. The resulting report will be a clear record on whether recommended ANC interventions have been implemented. Those that might be expected to be implemented in a sub-Saharan African country with endemic malaria and a generalised HIV epidemic are illustrated in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

ANC interventions during pregnancy in the enrolled cohort

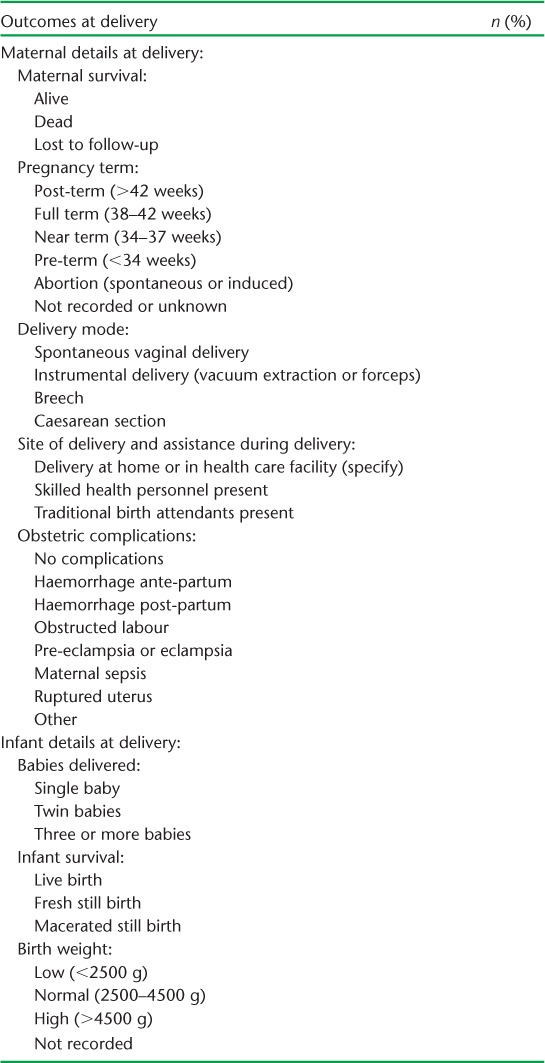

Information about the number of antenatal visits, laboratory investigations and medical treatments is again valuable in assessing whether the clinic is performing its ANC according to recommended practices. If performance is poor in certain areas, then interventions need to take place; quarterly assessments allow the clinic and the programme to determine whether there is improvement over time. Finally, the events at delivery for this registered cohort of pregnant women need to be recorded both for the mother and for the child, as illustrated in Table 3. Data on maternal and infant survival are important end-of-term parameters against which to assess the quality of ANC and the management of labour. Quantification of the different modes of delivery and the types of obstetric complications can help maternity health centres forecast and determine the material and financial resources and skilled personnel needed to ensure quality care.

TABLE 3.

Maternal and child outcomes at delivery

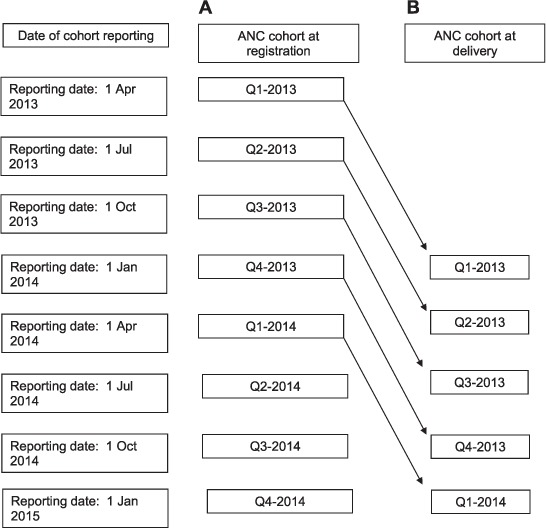

The reporting of monthly or quarterly ANC cohorts should be aligned with the reporting of that cohort's ANC and delivery outcomes. One way of doing this for quarterly cohorts is shown in the Figure. Once the system is set up and has been running for ⩾9 months, the clinic needs to report every quarter on the new cohort of pregnant women enrolled in care, and the ANC and delivery outcomes of the cohort enrolled 9 months earlier. This is similar to how the national TB programmes report on their cohort data at facility and national level. However, as stated earlier, the outcome reports will depend on the usual gestational age at which mothers present, and 6 months might be better in some countries than 9 months.

FIGURE.

Dates of reporting of A) the antenatal quarterly cohort at registration and B) the antenatal quarterly cohort at time of delivery (9 months later). ANC = antenatal care; Q = quarter.

Running paper-based record systems is possible for this type of cohort analysis, but a real-time, point-of-care electronic medical record system similar to that used for ART in Malawi,11 or for the management of DM and hypertension in Jordan,6,7 would be a better alternative. Such an electronic medical record system currently operates, for example, in Bwaila Maternity Health Centre in Lilongwe, Malawi, where almost 18 000 deliveries are recorded each year.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

With the expansion of global TB control worldwide and the scaling up of ART in some of the poorest countries of the world, much has been learnt about how to monitor new cases coming on to treatment and the burden of disease and treatment outcomes, and these have become the vital signs used to manage and evaluate these two treatment programmes.3,12

In Malawi, simple aggregation of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV infection from ‘traditional’ visit-based ANC registers had resulted in inflated coverage estimates due to the inability to distinguish women and visits, leading to double counting of women who were marked as ‘on ART drugs’ at consecutive visits. The development of a new PMTCT strategy in 2011, called ‘Option B+’,13 led to a cohort monitoring system similar to that described in this perspective article, and quarterly cohort reports have since become the established method of reporting on PMTCT and ART uptake in pregnant women.4

We believe that a cohort monitoring approach for ANC can be used in all health facility settings and that they should be adjusted to fit with the current epidemiology of disease in that country or region. For mothers who deliver outside of the health facility, monitoring of any kind will be a challenge. However, it is important that health care delivery within facilities be as good as possible. In these settings, there is a need for regular, structured and rigorous monitoring of interventions to determine whether the quality of care is good and whether this is making a difference to maternal health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Programme. A framework for effective tuberculosis control. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1994. WHO/TB/94.179. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Malawi, Ministry of Health. Integrated HIV program report, April to June 2013. Lilongwe, Malawi: MoH; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allain T J, van Oosterhout J J, Douglas G P et al. Applying lessons learnt from the ‘DOTS’ tuberculosis model to monitoring and evaluating persons with diabetes mellitus in Blantyre, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khader A, Farajallah L, Shahin Y et al. Cohort monitoring of persons with diabetes mellitus in a primary healthcare clinic for Palestine refugees in Jordan. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1569–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khader A, Farajallah L, Shahin Y et al. Cohort monitoring of persons with hypertension: an illustrated example from a primary healthcare clinic for Palestine refugees in Jordan. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1163–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241503631_eng.pdf Accessed April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogan M C, Foreman K J, Naghavi M et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards the Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375:1609–1623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell O M, Graham W J. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368:1284–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas G P, Gadabu O J, Joukes S et al. Using touchscreen electronic medical record systems to support and monitor national scale-up of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. PLOS MED. 2010;7:e1000319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization/UNICEF/UNAIDS. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schouten E J, Jahn A, Midiani D et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the health-related Millennium Development Goals: time for a public health approach. Lancet. 2011;378:282–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]