Abstract

Setting: Butaro Cancer Centre of Excellence (BCCOE), Burera District, Rwanda.

Objectives: To describe characteristics, management and 6-month outcome of adult patients presenting with potentially surgically resectable cancers.

Design: Retrospective cohort study of patients presenting between 1 July and 31 December 2012.

Results: Of 278 patients, 76.6% were female, 51.4% were aged 50–74 years and 75% were referred from other district or tertiary hospitals in Rwanda. For the 250 patients with treatment details, 115 (46%) underwent surgery, with or without chemotherapy/radiotherapy. Median time from admission to surgery was 21 days (IQR 2–91). Breast cancer was the most common type of cancer treated at BCCOE, while other forms of cancer (cervical, colorectal and head and neck) were mainly operated on in tertiary facilities. Ninety-nine patients had no treatment; 52% of these were referred out within 6 months, primarily for palliative care. At 6 months, 6.8% had died or were lost to follow-up.

Conclusion: Surgical care was provided for many cancer patients referred to BCCOE. However, challenges such as inadequate surgical infrastructure and skills, and patients presenting late with advanced and unresectable disease can limit the ability to manage all cases. This study highlights opportunities and challenges in cancer care relevant to other hospitals in rural settings.

Keywords: operational research, rural care, solid cancers, surgery, Africa

Abstract

Contexte : Centre anticancéreux d'excellence de Butaro (BCCOE), District de Butera, Rwanda.

Objectifs : Décrire les caractéristiques, la prise en charge et les résultats à 6 mois de patients adultes se présentant avec des cancers potentiellement extirpables par chirurgie.

Schema : Etude rétrospective de cohorte des patients admis entre le 1er juillet et le 31 décembre 2012.

Resultats : Sur 278 patients, 76,6% étaient des femmes, 51,4% étaient âgés entre 50 et 74 ans et 75% étaient référés d'un autre district ou d'un hôpital tertiaire du Rwanda. Parmi les 250 patients dont les traitements étaient connus, 115 (46%) ont bénéficié d'une intervention chirurgicale avec ou sans chimiothérapie/radiothérapie. Le temps médian écoulé entre l'admission et la chirurgie était de 21 jours (IQR 2 à 91). Le cancer du sein était le plus fréquent des cancers traités au BCCOE, tandis que les autres cancers (col utérin, colorectal et tumeur cérébrale ou cervicale) étaient généralement opérés dans des hôpitaux tertiaires. Quatre-vingt-dix-neuf patients n'ont eu aucun traitement ; 52% ont été référés à l'extérieur dans les 6 mois, généralement pour un traitement palliatif. A 6 mois, 6,8% étaient décédés ou perdus de vue.

Conclusion : De nombreux patients référés au BCCOE pour cancer ont bénéficié d'une intervention chirurgicale. Cependant la prise en charge de tous les cas est confrontée à la limite de capacité chirurgicale et au problème des patients admis tardivement avec un cancer avancé et non extirpable. Cette étude met en lumière les opportunités et les défis de la prise en charge des cancers pour les hôpitaux situés en zone rurale.

Abstract

Marco de Referencia: El Centro Butaro de Excelencia en Cáncer (BCCOE) del distrito de Burera, en Ruanda.

Objetivos: Describir las características, el manejo y el desenlace clínico a los 6 meses de pacientes adultos que se presentaron con cánceres cuyo tratamiento quirúrgico podía ser viable.

Métodos: Fue este un estudio retrospectivo de cohortes de los pacientes que acudieron al centro entre el 1° de julio y el 31 de diciembre del 2012.

Resultados: Se incluyeron en el estudio 278 pacientes, de los cuales 76,6% eran de sexo femenino, 51,4% tenían entre 50 y 74 años de edad y 75% habían sido remitidos de otro hospital distrital o de centros de atención terciaria de Ruanda. De los 250 expedientes que contaban con detalles sobre el tratamiento, en 115 casos (46%) los pacientes recibieron tratamiento quirúrgico con o sin quimioterapia o radioterapia. La mediana del lapso entre la hospitalización y la cirugía fue 21 días (intervalo intercuartil de 2 a 91). El cáncer de mama fue el tipo más frecuente de cáncer que se trató en el BCCOE y la cirugía de otras formas de cáncer (cuello uterino, colorrectal y de cara y cuello) se realizó principalmente en centros de atención terciaria. Noventa y nueve pacientes no recibieron tratamiento; el 52% de estos se remitió a otras instituciones en los primeros 6 meses, esencialmente con el propósito de recibir tratamiento paliativo. A los 6 meses, el 6,8% de los pacientes había fallecido o se habían perdido durante el seguimiento.

Conclusión: Muchos de los pacientes remitidos recibieron tratamiento quirúrgico en el BCCOE. Sin embargo, la posibilidad de tratar todos los casos se ve limitada por obstáculos como una capacidad quirúrgica inadecuada y el hecho de que los pacientes acuden tarde, en una fase avanzada de la enfermedad, con un cáncer inoperable. El presente estudio pone de relieve oportunidades y dificultades en el tratamiento del cáncer que son pertinentes para otros centros hospitalarios en un entorno rural.

Cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the developing world, with the majority of cancer deaths now occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) global cancer database (GLOBO-CAN) estimated that approximately 715 600 new cases of cancer occur annually in Africa.2 However, despite this enormous burden of disease, the capacity for diagnosis and treatment of cancer in this region is limited.3,4

While some cancers can be treated effectively with curative intent with systemic chemotherapy alone, the common epithelial cancers seen in both LMICs and high-income countries (HICs) all require surgical resection of early-stage disease if there is to be a chance for long-term cure, particularly breast, cervical, colorectal and prostate cancer. The chance of cure is dependent on the stage at presentation—the earlier the stage, the higher the chance of cure—and the capacity of the health service to perform adequate surgery. If the primary tumour has metastasised, there is no chance of cure, even at cancer centres in HICs. If a patient presents with early-stage disease, but there is no capacity for effective surgical treatment, the chance of cure is zero.

Development of a cancer-care infrastructure in LMICs is a complex undertaking requiring the capacity to assess and diagnose cancers accurately (including pathology evaluation), and the administration of appropriate systemic treatment (chemotherapy, hormone or targeted treatment) and/or radiation. Cancers amenable to surgery provide additional challenges for care, as they further rely on surgical infrastructure.5,6 Specialised training in cancer surgery is thus required for optimal long-term outcomes.

In Africa in 2008, the most frequent cancer diagnosis in men (prostate) and the two most frequent in women (breast and uterine cervix) were amenable to surgery.7 However, there is evidence that many patients with potentially surgically resectable cancer present late in the course of the disease,3 reducing the effectiveness of surgical and medical treatment. Rwanda, a small country in Central/Eastern Africa, has taken important steps to address this growing burden of cancer. In July 2012, Butaro District Hospital opened the first dedicated rural cancer treatment centre in rural East Africa, the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence (BCCOE). This centre has facilities for both in- and out-patient care and resources for a more accurate diagnosis of cancer and potentially better outcomes of treatment. Information from such a centre would provide valuable insights into the burden and management of surgically resectable cancer in Africa.

The aim of this study was to describe the demographic characteristics, referral patterns, management and outcomes of patients presenting with potentially surgically resectable cancers.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective descriptive study using routinely collected records of a cohort of patients presenting with potentially surgically resectable cancers, defined as cancers where surgery is a required component of care for patients with early-stage disease.

Setting

General

Rwanda remains Africa's most densely populated country, with an estimated population of 11 million, expected to rise to 16 million by 2020.8 A combination of a growing population, increasing life expectancy, better control of communicable diseases and rising standards of living have resulted in cancers and other non-communicable diseases rapidly becoming a major health concern, a situation common in other LMICs.5,9

Site

Rwanda has five tertiary and 40 district hospitals. The BCCOE, established in mid-2012 in Butaro District Hospital, is supported by Partners In Health, a US-based non-governmental organization, and its sister organisation Inshuti Mu Buzima, a Rwandan-based non-governmental organisation. It aims to provide a comprehensive range of diagnostic and treatment services for patients with cancer, and to be the first facility to implement standardised training in cancer care using protocols that will be included in Rwanda's forthcoming new national guidelines.

The centre staff includes two internists, one general surgeon and one gynaecologist (both shared with the district hospital for general surgical/gynaecological needs), two general practitioners and 10–13 nurses. Additional support is available from visiting international pathologists, surgeons, oncologists and oncology nurses. Services offered include 22 beds for in-patient care, biopsies and on-site histopathology (augmented by sending specimens abroad for special staining procedures, as previously described10). Onsite imaging includes ultrasound and X-ray, with computed tomography (CT) and medical resonance imaging (MRI) scans available in the capital city (Kigali) where necessary. General surgery is available at BC-COE, while specialised surgery is available at tertiary hospitals in Kigali. Chemotherapy is delivered by internists and supervised by a network of visiting oncologists, with weekly remote consultation from US-based oncology specialists. Radiotherapy is performed in neighbouring Uganda. Social support includes health facility transportation, nutritional supplementation and additional support for poor patients, such as home construction. Palliative care is often provided at a district hospital closer to the patient's residence. Patients usually access the BCCOE through referral from other health facilities in Rwanda or from outside the country (primarily Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo).

Clinical information on in- and out-patients is collected in paper-based medical files. From these, selected data are entered by a data officer into an electronic medical record (EMR), which can serve as a clinical database. Information about surgical procedures is currently kept in the patient's medical files.

Study population

All adult patients aged ⩾18 years with potentially surgically resectable cancers enrolled in care at the BC-COE, Rwanda, between 1 July and 31 December 2012 were included in the study. Individuals included in the database might have had cancers amenable to surgery if they had presented early enough, but are included irrespective of stage of disease.

Source of data, data collection and analysis

Variables extracted from the EMR included demographics; type and perceived stage of cancer (confirmed stage not available, perceived stage based on clinical assessment, indicating the clinician's perception of disease severity but not necessarily matched to a specific staging system); type of facility from which patient was referred; and 6-month outcomes—alive, dead, referred elsewhere for care or lost to follow-up (defined in this study as not attending scheduled clinic visits after 6 months). In patients alive at 6 months, data available on patient progress (improvement, no evidence of disease, progression of cancer) were extracted from the EMR. Incomplete and inconsistent data from the EMR were completed or verified from patient paper records. Data on the method of diagnosis (histopathology or clinical) and medical treatment (surgical intervention, chemotherapy or combined surgery and chemotherapy) were extracted from the patient files into Excel® (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). Patient data were collected in November 2013.

Analyses were completed using Stata v12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Frequencies and proportions of patient characteristics at admission to BCCOE, patient management and patient 6-month outcomes are presented.

Ethics

The study received technical approval from the National Health Research Committee. Ethics approval was obtained from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France. The study also met the Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Review Board-approved criteria for analysis of routinely collected programme data.

RESULTS

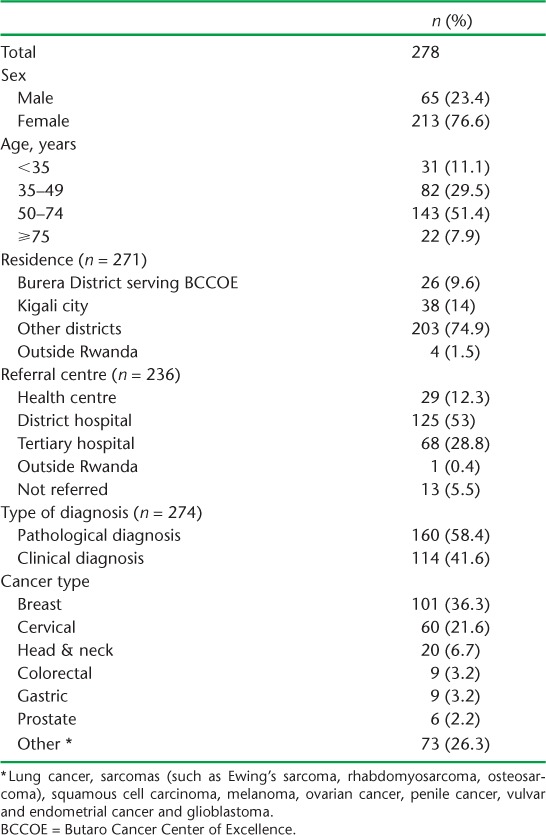

There were 278 patients enrolled in the oncology programme at BCCOE with potentially surgically resectable cancers. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority (76.6%) of the patients were female, and 143 (51.4%) were aged between 50 and 74 years (median age 53 years). Among patients with residence records, most (74.9%) were from outside Burera District, Rwanda. The most common surgically resectable cancers were breast, cervical, head and neck, colorectal and gastric cancers.

TABLE 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients presenting at BCCOE, Rwanda, with surgically resectable cancers, July–December 2012

Fifty-eight per cent of diagnoses were based on histopathology. If uterine cervical cancers are excluded, this rises to 70.4%. (Cervical cancer in Rwanda can often be diagnosed clinically.)

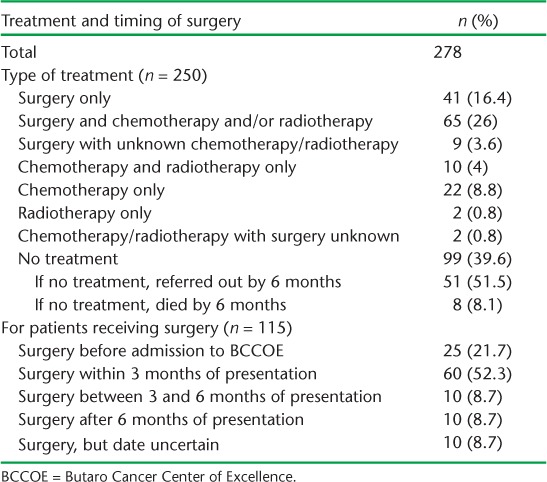

Treatment and timing of surgery are shown in Table 2. Of the 250 patients with treatment data, 115 (46%) underwent surgery either alone or with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and an additional 36 (14.4%) underwent chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy without surgery. Ninety-nine (39.6%) patients had no treatment. Of these, 51/99 (51.5%) were referred to another facility for care, primarily due to advanced disease and the need for palliative care, eight died before treatment was started and the remainder had not started treatment during the study period. Presumed staging at presentation was only available for 99 patients, with surgery data available for 96. Of the 39 with presumed Stage 1/2, 24 (61.5%) received surgery compared to 22/57 (38.6%) with presumed Stage 3/4 (P = 0.027).

TABLE 2.

Treatment and timing of surgery for surgically resectable cancers in patients presenting at BCCOE, Rwanda, July–December 2012

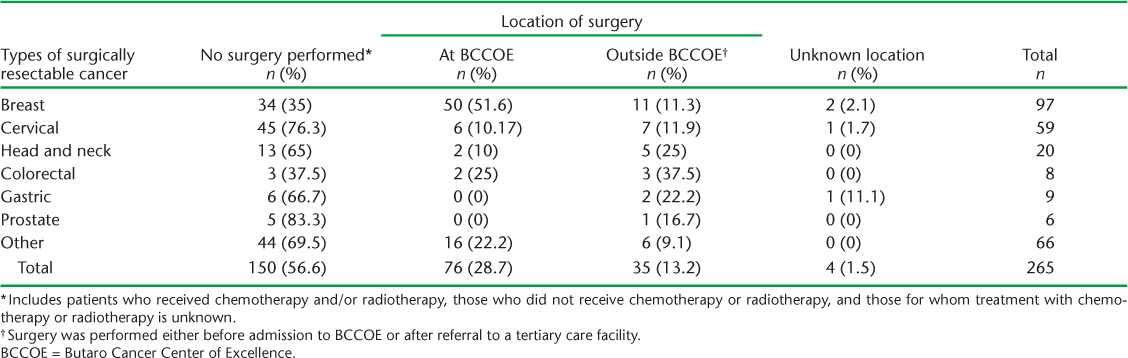

Of the 76 patients who underwent surgery at BCCOE, nearly 70% did so within 3 months of initial presentation. The median time from presentation to surgery was 21 days (interquartile range [IQR] 2–99). Surgical treatment in relation to different types of cancer and place of surgery is shown in Table 3. A total of 150 patients (56.6% of total) had no surgery. Breast cancer was the most common type of cancer operated on in BCCOE. Thirty-five of the 115 patients who had surgery (30.4%) did so outside BCCOE, including 5/7 head and neck cancer surgeries and 3/5 colorectal cancer surgeries.

TABLE 3.

Surgical procedures and location by cancer type

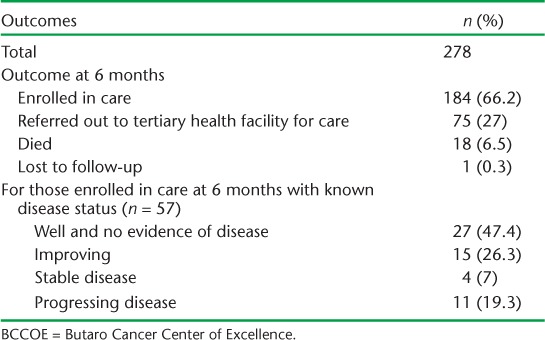

Six-month treatment outcomes are shown in Table 4. Most patients (66.2%) were still in care at BCCOE, and 27% had been referred out for care. Nineteen patients (6.8% of total) had an adverse outcome of death or loss to follow-up. Limiting the analysis to cancer types with ⩾20 cases, there was variability in outcome, with breast cancer having the highest rate of enrolment in care at 6 months (83.2%) and cervical cancer having the highest rates of referral out for care (40.9%). Only two patients were documented to have died after receiving surgery, and both deaths occurred several months after surgery, suggesting that post-operative mortality (mortality within 30 days of surgery) in these patients was low. Of those patients still in care and for whom information was known, 73.4% were well and had no clinical evidence of disease or were improving.

TABLE 4.

Six-month outcomes for patients with potentially surgically resectable cancers at BCCOE, Rwanda

DISCUSSION

This study describes the profile and management of potentially surgically resectable cancers at BCCOE, the first dedicated cancer treatment centre in rural East Africa. During its first 6 months, the centre admitted 278 patients with cancers for which surgery plays an important role in early-stage disease. Breast cancer, followed by cervical cancer and head and neck cancer were the most common cancers seen. Over half of the patients had histopathological diagnoses recorded in their charts. This is probably a lower bound for the proportion with histopathology, as it is possible that a diagnosis was received but not documented in the patient file. However, the percentage with confirmed histopathology diagnosis is still higher than that reported from other sub-Saharan African countries with similarly low resources.11,12

The focus of this study was cancers for which surgery for early-stage patients is an essential component of treatment; however, it is possible that the patients described presented with disease too advanced for surgery to be applicable. Approximately 40% of the patients did not receive any treatment in the centre; most of these were referred to another facility nearer to their homes for palliative care. Without details on clinical staging for the remaining patients, it is difficult to know whether surgery was not received due to late presentation or due to the lack of availability of services.

Of those undergoing treatment, the majority had surgery with or without adjunctive chemotherapy or radiotherapy, as appropriate. Breast cancer was the most common type of cancer operated on at our centre, while other forms of cancer, such as colorectal and head and neck cancer, were mainly operated on in other facilities. This reflects the inconsistent availability of surgical expertise to deal with these cancers at BCCOE. Six-month outcomes were generally good for those who remained in care, with few patients known to have died and only one patient lost to follow-up.

The strengths of this study lie in the fact that all consecutive patients enrolled in care at BCCOE were included, and thus there was no special selection of patients. Due attention was also paid to internationally agreed recommendations for reporting on observational studies.13 Limitations relate to the operational nature of this record review, with certain variables for which it would be important to have information not being available and data missing for other variables. We believe that the missing data are a function of adopting new data collection tools and that they are probably missing randomly. Another limitation is that the results reflect the burden of cancer among patients presenting at BCCOE and do not necessarily reflect the general incidence of these cancers in the population or presentation and/or management at other sites.

Several policy implications are derived from this study. First, many patients did not undergo surgery, possibly due to late presentation or to the limited surgical resources available at BCCOE. Surgical resources in Butaro are shared across all programmes, including BCCOE, and between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2013, 1018 surgical procedures were completed, with an average of 2–3 per day. There are only two operating rooms, and at time of writing 73 people were on the waiting list for surgery. These limitations apply to all surgical patients, and the capacity to manage the demand for surgically resectable cancer is currently lacking. During the period of this study, there was permanent capacity for breast and cervical cancer surgeries, but other cancer-related surgeries could only be performed by visiting specialists. The centre needs to decide whether and how to bridge this gap. The most realistic solution would be to identify promising health care professionals in Rwanda and ensure that they have the appropriate training and resources to eventually staff the centre. Treatment efforts should be coupled with prevention efforts, such as the promotion and use of vaccines against human papillomavirus (HPV) to prevent cervical neoplasia,14 to reduce future demand for treatment at BCCOE. Furthermore, and most importantly, these efforts must be coupled with a comprehensive screening programme that includes community education and training of primary health care staff, to ensure early presentation of patients, increasing the likelihood of long-term disease-free survival.

Second, the data collection system needs to be strengthened. Variables essential for evaluating innovation and progress need to be decided on, and ultimately it is best to capture all information in an electronic database system. Current revisions and structuring of patient charts should encourage more complete and reliable data collection in the future. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of these efforts is critical to know what is being accomplished, where gaps in care persist and how to design interventions to improve outcomes in the future.

Third, the centre's vision is to develop standardised cancer training and protocols that will be included in Rwanda's forthcoming new national guidelines. To realise this vision, rigorous documentation of experience, challenges, patient characteristics and outcomes in the centre and a continued close relationship with the leadership at the Rwandan Ministry of Health are required. Future research must explore long-term outcomes of these patients by cancer type and stage, and should explore the costs of different aspects of the oncology programme. Finally, resources are needed to support the expansion of services at BCCOE.

BCCOE is unique in being one of the first centres to offer cancer services in a rural setting in Africa. Early results are promising, but they highlight challenges and possible ways forward for BCCOE and other rural hospitals interested in adopting cancer care. Having or developing sufficient surgical infrastructure should be considered alongside the development of oncology programmes to maximise the benefits to patients with these highly curable cancers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through an operational research course that was jointly developed and run by the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Brussels Operational Centre, Luxembourg; the Centre for Operational Research, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France; and The Union South-East Asia Office, Delhi, India. Additional support for running the course was provided by the Institute for Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; the Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; the University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya and Partners In Health, Rwanda. This course is under the umbrella of the World Health Organization (WHO-TDR) SORT IT programme (Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative) for capacity building in low- and middle-income countries.

Funding for the course was provided by MSF Luxembourg, Brussels Operational Centre, Luxembourg, the Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Department for International Development (DFID), UK. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul F M et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet. 2010;376:1186–1193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61152-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin H R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin D M. GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/2010/globocan2008.php Accessed April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price A J, Ndom P, Atenguena E, Noemssi J P M, Ryder R W. Cancer care challenges in developing countries. Cancer. 2011;118:3627–3635. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morhason-Bello I O, Folakemi O, Rebbeck T R et al. Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: a perspective from the African Organisation for Research and Training in Cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e142–151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sankaranarayanan R, Boffetta P. Research on cancer prevention, detection and management in low- and medium-income countries. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1935–1943. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zogg C K. Recognition of surgical need as part of cancer control in Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e289. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D et al. Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer. 2012;118:4372–4384. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Republic of Rwanda, Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. Rwanda Vision 2020. Kigali, Rwanda: Government of Rwanda; 2000. http://www.gesci.org/assets/files/Rwanda_Vision_2020.pdf Accessed April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormack V A, Boffetta P. Today's lifestyles, tomorrow's cancers: trends in lifestyle risk factors for cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2349–2357. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson J W, Lyon E, Walton D et al. Partners in pathology: a collaborative model to bring pathology to resource poor settings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:118–123. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c17fe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Msyamboza K P, Dzamalala C, Mdokwe C et al. Burden of cancer in Malawi; common types, incidence and trends: national population-based cancer registry. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:149. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adesina A, Chumba D, Nelson A M et al. Improvement of pathology in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e152–157. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn J A. HPV vaccination for the prevention of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:271–278. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0806938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]