Abstract

In 2011, bi-directional screening for tuberculosis (TB) and diabetes mellitus (DM) was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), although how best to implement the activity was not clear. In India, with early engagement of national programme managers and all important stakeholders, a countrywide, multicentre operational research (OR) project was designed in October 2011 and completed in 2012. The results led to a rapid national policy decision to routinely screen all TB patients for DM in September 2012. The process, experience and enablers of implementing this unique and successful collaborative model of operational research are presented.

Keywords: operational research, TB-DM collaboration, policy

Abstract

En 2011, un double dépistage de la tuberculose (TB) et du diabète (DM) a été recommandé par l'Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS), mais il n'a pas été précisé clairement comment mettre en œuvre au mieux cette activité. En Inde, grâce à l'engagement précoce des directeurs de programmes nationaux et de tous les partenaires importants, un projet national de recherche opérationnelle (OR) multicentrique a été conçu en octobre 2011 et achevé en 2012. Les résultats ont rapidement amené à une décision politique nationale de dépister en routine tous les patients TB à la recherche de DM en septembre 2012. Cet article présente la procedure et l'expérience de ceux qui ont mis en œuvre ce modèle collaboratif de recherche opérationnelle assez unique et fructueux.

Abstract

En el 2011, la Organización Mundial de la Salud recomendó la detección bidireccional de la tuberculosis (TB) y la diabetes sacarina (DM), aunque no fue claro cuál sería el mejor mecanismo de ejecución de la iniciativa. En la India, con la participación temprana de los gestores del programa nacional y todos los principales interesados directos, se formuló un proyecto multicéntrico de investigación operativa de ámbito nacional en octubre del 2011 y se completó en el 2012. Los resultados llevaron a una rápida decisión política de alcance nacional en septiembre del 2012, de practicar la detección sistemática de la DM en todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de TB. En el presente artículo se describe el proceso, las experiencias y los factores facilitadores de la ejecución de este excepcional y eficaz modelo colaborativo de investigación operativa.

The interaction between tuberculosis (TB) and diabetes mellitus (DM) has been well documented: DM patients are at higher risk of developing TB, and individuals with both DM and TB are at higher risk of poor treatment outcomes.1 To address this dual burden, in 2011 the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) developed a collaborative framework for care and control of TB and DM that recommended that countries undertake several activities, including bidirectional screening for TB and DM.2 However, the operational guidelines on how best to implement this intervention in programme settings were lacking.

To bridge this gap, a countrywide, multicentre operational research (OR) project was designed and conducted in India in 2012 by The Union South-East Asia office in collaboration with the Indian Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP), the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS), the WHO and other stakeholders within the country. Financial support for meetings and for project coordination was provided by the World Diabetes Foundation (WDF). Results from this OR led to a national policy decision in September 2012 to routinely screen all TB patients notified under the RNTCP for DM in India. This decision was achieved in a short time frame within just a year of project conception.3,4 What factors made this rapid translation of evidence to policy possible? In this article, we describe the experience of implementing this collaborative model of operational research that led to policy change, and highlight some of the main enablers.

ASPECT OF INTEREST

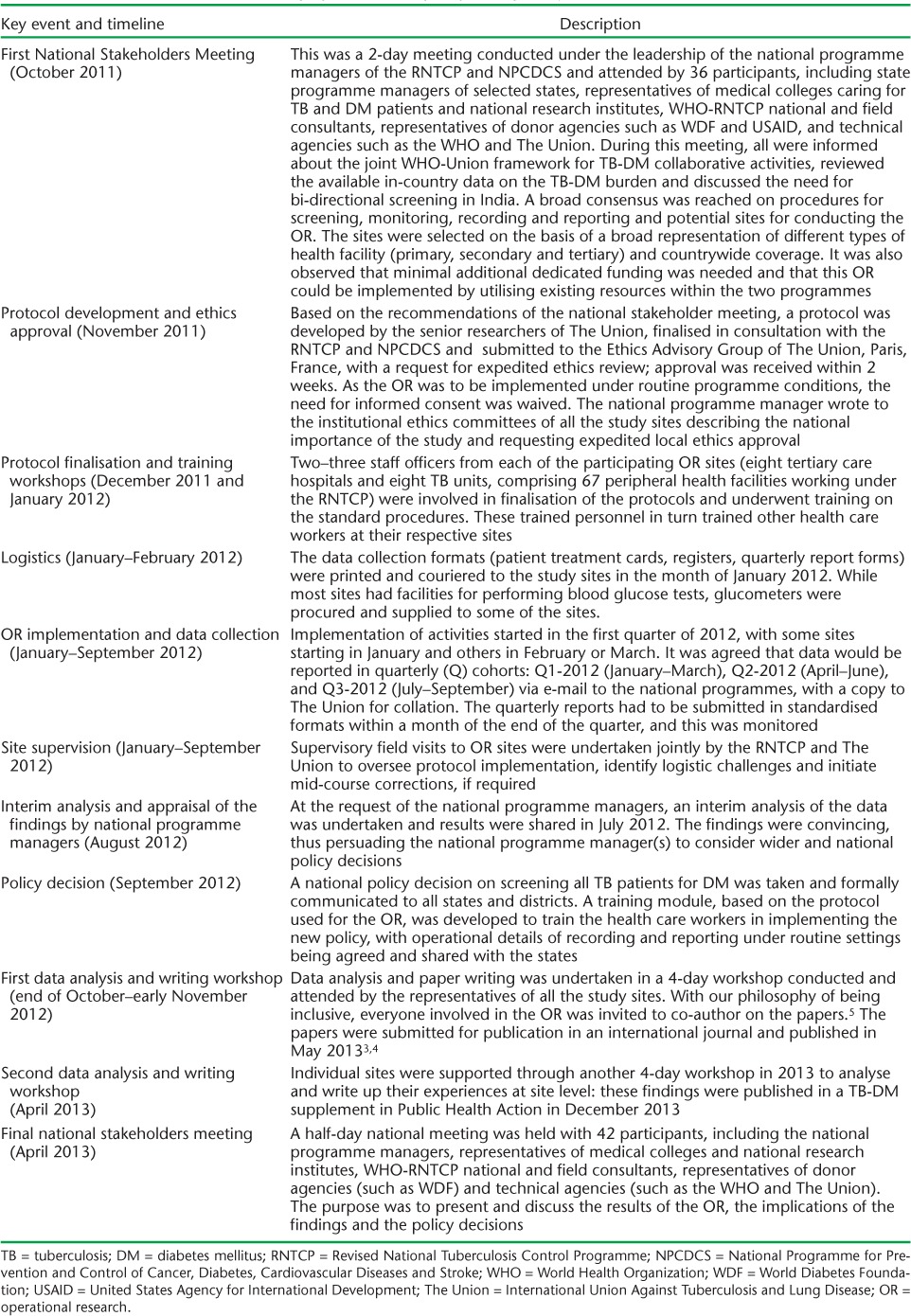

The timeline of key events from the conception of OR to the policy decision is described in Table 1. Briefly, it started with a national stakeholders meeting in October 2011 to agree broadly on the necessity for TB-DM collaboration and the need to generate high-quality evidence for programme decisions using well-planned OR. Key principles about where to conduct the OR, how to screen for DM and TB and how to record and report the findings were discussed and agreed upon.

TABLE 1.

Timelines and events leading up to national policy change on joint TB and DM collaboration in India

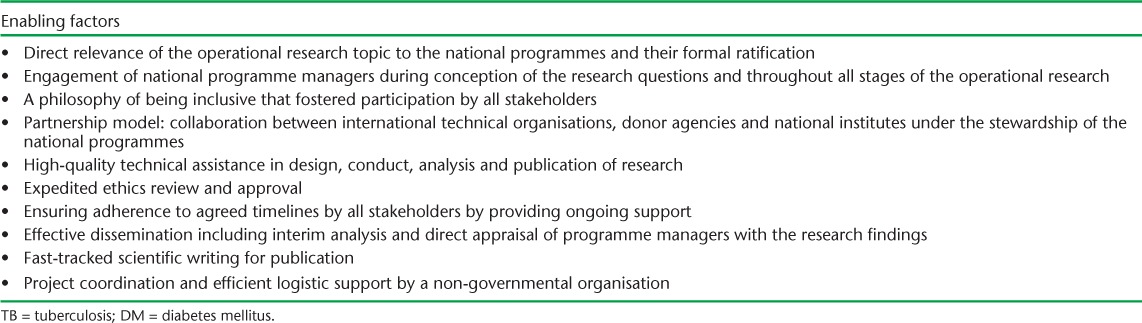

Following this meeting, a national protocol was developed, OR sites were identified (based on their willingness to participate in the study) and ethics approval was obtained for writing up the findings. Staff from the participating sites were then trained in screening, recording and reporting procedures. The quality of the protocol implementation was monitored by supervisory visits and submitted reports were validated by cross-matching the data with the records. An interim analysis in August 2012 showed that it was feasible to perform bi-directional screening, and that screening identified a significant proportion of undiagnosed DM among TB patients. This led the programme managers of the RNTCP and NPCDCS to decide on the policy change in September 2012, before the full study results were available. After completion of the study, a data analysis and writing workshop was conducted, resulting in several publications.3,4,6 A final national stakeholders meeting was held soon after, at which the findings and policy decisions were presented to a large audience. A training manual was drafted for health care workers based on the experience of the OR project which details the screening procedures and recording and reporting mechanisms to be conducted under the RNTCP. The key factors that enabled this national policy change are summarised in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Enabling factors for rapid translation of evidence to policy on TB and DM collaboration, India

DISCUSSION

The OR project was carried out rapidly with programme and stakeholder participation, and the findings were swiftly translated into national policy. There were several important enabling factors. First, OR was conducted on a topic that was of direct relevance to both programmes. India has the highest burden of TB in the world and the second highest burden of DM,7,8 and interaction between the two diseases is of major public health importance.

Second, the national programme managers were involved from the conception of the OR to the dissemination of findings and eventual publication. The approach of involving them early on in the process fostered their sense of ownership and responsibility, which in our opinion was key to making rapid progress. This is in contrast to much research in which the publication milestone has become the end-point, with little consideration given to what happens afterwards. As such, engagement with programme managers and policy makers is not seen as a priority.9,10

Third, the participation of key stakeholders (for example, technical and donor agencies) working in TB and DM care in the country helped to achieve a national consensus and wide ownership of the results, thus creating many advocates for policy change.

Fourth, there was high-quality technical assistance from senior researchers of The Union, the WHO and national research institutes right from protocol development to data analysis and drafting scientific manuscripts.

Ethics approval, which often delays research projects, was rapidly obtained. As there was approval from the Ethics Advisory Group of The Union and a communication from the national programme manager(s) reiterating the national importance of the OR, the need to assess feasibility of bidirectional screening under routine conditions and the fact that the study involved extracting data from records with no patient interview, the institutional ethics committees of the participating sites also expedited ethics approval and waived the need for individual informed consent.

Fifth, the inclusive philosophy meant that all stakeholders were involved at the different stages of the research process and were deservingly credited as co-authors of papers in line with the criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.11 While it was a challenge to achieve consensus among such a large group, innovative approaches were employed as described elsewhere.5

Sixth, collaborative research projects involving multiple partners often face implementation delays for a variety of reasons. We undertook several pre-emptive measures to mitigate delays, including prior agreement and strict monitoring of adherence to project timelines, supervisory site visits and leadership by the national programmes, all of which helped to identify and resolve logistic issues in a timely fashion.

Finally, The Union (a non-governmental organisation) undertook the responsibility for coordinating the project logistics — support that was very much welcomed by the national programme managers. With the policy and operational guidance for implementation now in place, the next major challenges are to ensure that it is implemented on the ground and to monitor its impact on health outcomes. While TB services are available throughout the country, the same cannot be said of DM care services, which are currently available only in around 100 districts. The success of this joint collaboration will thus depend heavily on the pace of scale-up of the NPCDCS, which aims to expand DM care services to the entire country by 2017.

In conclusion, this model of operational research, which fostered a high sense of ownership and which was propelled by the national programme managers in collaboration with the technical and donor agencies, worked rapidly and efficiently. This experience offers useful lessons for the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff at the hospitals and peripheral health facilities of the participating sites for their support in managing and monitoring TB and DM patients and their help in data collection.

We thank the World Diabetes Foundation for supporting the training modules and the stakeholder meetings in India that facilitated the design and implementation of the OR project. We thank the Department for International Development (DFID), UK, for supporting Ajay MV Kumar and Srinath Satyanarayana as senior operational research fellows.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Harries A D, Satyanarayana S, Kumar A M V et al. Epidemiology and interaction of diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis and challenges for care: a review. Public Health Action. 2013;3(Suppl):S3–S9. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, World Health Organization. Collaborative framework for care and control of tuberculosis and diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. p. 40. WHO/HTM/TB/2011.15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.India Diabetes Mellitus-Tuberculosis Study Group. Screening of patients with diabetes mellitus for tuberculosis in India. Trop Med Intern Health. 2013;18:646–654. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.India Tuberculosis-Diabetes Study Group. Screening of patients with tuberculosis for diabetes in India. Trop Med Intern Health. 2013;18:636–645. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satyanarayana S, Kumar A M V, Sharath B N, Harries A D. Fast-track writing of a scientific paper with 30 authors: how to do it. Public Health Action. 2012;2:186–187. doi: 10.5588/pha.12.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satyanarayana S, Kumar A M V, Wilson N, Kapur A, Harries A D, Zachariah R. Taking on the diabetes-tuberculosis epidemic in India: paving the way through operational research. [Editorial] Public Health Action. 2013;3(Suppl):S1–S2. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 6th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2011. http://www.eatlas.idf.org Accessed April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zachariah R, Ford N, Maher D et al. Is operational research delivering the goods? The journey to success in low-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:415–421. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zachariah R, Reid T, Van den Bergh R et al. Applying the ICMJE authorship criteria to operational research in low-income countries: the need to engage programme managers and policy makers. [Editorial] Trop Med Intern Health. 2013;18:1025–1028. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. Chapter II: Ethical Considerations in the Conduct and Reporting of Research. A: Authorship and Contributorship. ICMJE 2004 update. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/archives/2004_urm.pdf Accessed June 2014.