Abstract

This study investigated the formulation of a two-component biodegradable bone cement comprising the unsaturated linear polyester macromer poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF) and crosslinked PPF microparticles for use in craniofacial bone repair applications. A full factorial design was employed to evaluate the effects of formulation parameters such as particle weight percentage, particle size, and accelerator concentration on the setting and mechanical properties of crosslinked composites. It was found that the addition of crosslinked microparticles to PPF macromer significantly reduced the temperature rise upon crosslinking from 100.3 ± 21.6 to 102.7 ± 49.3 °C for formulations without microparticles to 28.0 ± 2.0 to 65.3 ± 17.5 °C for formulations with microparticles. The main effects of increasing the particle weight percentage from 25 to 50% were to significantly increase the compressive modulus by 37.7 ± 16.3 MPa, increase the compressive strength by 2.2 ± 0.5 MPa, decrease the maximum temperature by 9.5 ± 3.7 °C, and increase the setting time by 0.7 ± 0.3 min. Additionally, the main effects of increasing the particle size range from 0–150 μm to 150–300 μm were to significantly increase the compressive modulus by 31.2 ± 16.3 MPa and the compressive strength by 1.3 ± 0.5 MPa. However, the particle size range did not have a significant effect on the maximum temperature and setting time. Overall, the composites tested in this study were found to have properties suitable for further consideration in craniofacial bone repair applications.

Keywords: bone tissue engineering, poly(propylene fumarate), injectable biomaterial, in situ crosslinkable

Introduction

Treatment of osseous defects in the craniofacial complex remains a significant challenge to clinicians. Due to conditions such as tumor resections 1, trauma 2, or congenital disorders 3, the surgical replacement of bone in the craniofacial region is a relatively common procedure. In addition to restoration of the functional aspects of tissues, reconstructive procedures in the head and neck must also address aesthetic features in order to maintain quality of life for the patient 4.

The current gold standard for definitive treatment of osseous craniofacial defects is autografting. Despite its widespread use and clinical success, complications such as donor site morbidity and the associated reduced quality of life and pain, increased operative time, and risk for further fractures are common 5–8. Thus, the potential exists for other strategies, such as the use of alloplastic materials, to have a clinical impact. The literature describes the ideal biomaterial for craniofacial bone repair as biocompatible, mechanically stable enough to resist trauma, and easily shaped or molded 9,10. In compliance with these criteria, poly(methylmethacrylate) bone cement has been used in craniofacial bone applications since the mid-1990s. The acrylic resin is moldable in situ, but its high curing temperature can damage local tissues 11,12, especially in the sensitive areas of the head and neck. This material is advantageous in cost and availability, but lacks the ability to degrade, thus making it impossible to fully restore the patient’s native tissue or adjust the facial contour at a later point in time if implanted permanently, or requiring an additional surgery for removal if implanted temporarily. Therefore, the need exists for a material that satisfies the aforementioned criteria for craniofacial bone repair while presenting the ability to degrade.

Poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF), is an unsaturated, linear polyester macromer that has been developed in our laboratory for a variety of orthopaedic applications. Previous studies have shown crosslinked PPF to be biodegradable13–16, biocompatible 14,17,18, osteoconductive 14,19–21, and to possess sufficient compressive strength for orthopaedic applications 22,23. Other issues such as the setting and injectability characteristics are also important for clinical consideration. In this regard, in order to obtain sufficient setting times for in situ forming applications with PPF, an accelerator must be present in the reaction, increasing the setting temperature above that of PMMA.

To mitigate this problem, the objective of this study was to investigate the reduction in temperature rise upon crosslinking of PPF by incorporating crosslinked PPF microparticles into the mixture, and to evaluate the validity of this material for clinical applications by characterizing the setting and mechanical properties. The material was made by formulating PPF into a two-phase system analogous to that of clinically available PMMA bone cement, consisting of a powder phase of crosslinked PPF microparticles and an initiator, benzoyl peroxide (BP); and a liquid phase of PPF macromer, the crosslinking agent N-vinyl pyrrolidone (NVP), and the accelerator dimethyl toluidine (DMT). Particle weight percentage, particle size range, and DMT concentration were varied in a full factorial design in order to determine their effects on the compressive modulus, compressive strength, maximum crosslinking temperature, setting time, and injectability of composites. Desirable properties for this application include a significantly reduced crosslinking temperature over clinically used PMMA; a clinically relevant setting time of 5–11 minutes24,25; a compressive modulus and strength of at least 200 and 10 MPa26,27, respectively, to resist trauma; and the ability to be injectable. It was envisioned that the PPF formulations tested in this study would satisfy many of the design criteria outlined for biomaterials in craniofacial applications, as does clinically available PMMA bone cement.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Diethyl fumarate, propylene glycol, NVP, DMT, and BP were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used as received. All solvents for PPF purification were purchased from Fisher (Pittsburg, PA) as reagent grade and used as received. Medium viscosity SmartSet bone cement was supplied by DePuy Orthopaedics (Warsaw, IN) (solid phase: 67.05 wt % poly(methyl methacrylate), 21.10 wt % methylmethacrylate/styrene copolymer, 1.85 wt % benzoyl peroxide, 10.00 wt % barium sulphate; liquid phase: 98.00 wt % methyl methacrylate, ≤2.00 wt % N,N-dimethyl toluidine, 75 ppm hydroquinone).

PPF Synthesis and Microparticle Fabrication

PPF was synthesized according to established methods 28,29. The molecular weight was confirmed via gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Waters, Milford, MA) using polystyrene standards (Fluka, Switzerland). PPF with a number average molecular weight of 3300 and a polydispersity index of 1.7 was used in this study.

PPF microparticles were synthesized by grinding crosslinked PPF rods. Briefly, a solution of PPF and NVP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was combined in a 4:1 mass ratio and benzoyl peroxide (BP, Sigma-Aldrich) was added in 2 wt % of the total PPF/NVP solution. The solution was then poured into 15 mm diameter × 60 mm height poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE) molds and crosslinked at 60°C for 24 hours. Then, the rods were removed, broken into smaller pieces using a hammer, and ground into powder using a grinder (Mr. Coffee, Cleveland, OH, model IDS 55). The ground powder was then sieved into 0–150 μm and 150–300 μm fractions using brass sieves (Dual Manufacturing Co., Chicago, IL).

Experimental Design

Experiments were based on a two-level full factorial design with three parameters: (1) particle weight percentage, (2) particle size range, and (3) DMT concentration. High and low levels were chosen based on previous experience, and these levels were combined to create eight experimental formulations. Additionally, formulations containing no particles (formulations A and B) and commercially available PMMA bone cement were used as controls. The values for all parameters are shown in Table 1. The properties of interest of each formulation included compressive modulus and strength, maximum crosslinking temperature, setting time, and injectability. The results from each experiment were used to determine the main effects of each parameter on the property of interest.

Table 1.

| (a) High and Low Levels for Three Parameters Tested in a Two-Level Full Factorial Design | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Particle Content (wt %) | Particle Size Range | DMT/PPF |

| High (+) | 50 | 150–300 μm | 0.1 μl/1.0 g |

| Low (−) | 25 | 0–150 μm | 0.05 μl/1.0 g |

| (b) Combinations of the Experimental Variables in the Full Factorial Design. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation | Particle Content (wt %) | Particle Size Range | DMT/PPF |

| A | 0 | N/A | + |

| B | 0 | N/A | − |

| C | − | − | + |

| D | − | − | − |

| E | − | + | + |

| F | − | + | − |

| G | + | − | + |

| H | + | − | − |

| I | + | + | + |

| J | + | + | − |

Formulations A and B were used for comparison and did not contain PPF microparticles.

Composite Fabrication

Crosslinked composites were fabricated using a two phase combination technique. The first phase, a powder component of crosslinked PPF microparticles and 0.02 g of BP per g of liquid PPF/NVP (found in the second phase), was combined and mixed with a spatula. The second phase, a liquid, was composed of a solution of PPF macromer and NVP in a weight ratio of 1:1 with either 0.05 or 0.1 μl of DMT per g of PPF/NVP. Composites were produced by combining both components in either a 1:1 or 1:3 powder:liquid ratio in a beaker and stirring vigorously for 1 min with a spatula before packing into the appropriate mold.

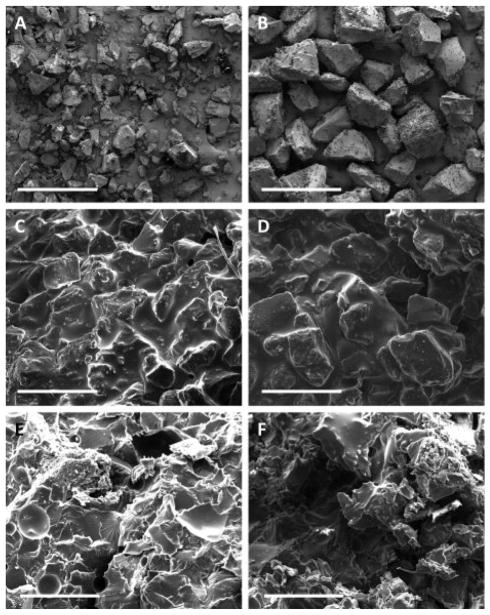

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy samples were prepared by placing particles or composites on sample holders and sputter coating with approximately 20 nm of gold using a CrC-150 Sputter Coater (Torr International, New Windsor, NY). The top surface of each sample was viewed using a Quanta 400 Electron Microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) operated at 15kV.

Compressive Strength and Modulus

The compressive mechanical properties of the composites were measured to establish the influence of PPF microparticle incorporation on mechanical performance. In accordance with ASTM D792-08, 6 mm diameter × 12 mm height cylindrical constructs (n = 6) were compressed along their long axis at a cross-head speed of 1 mm/min using a mechanical testing machine (MTS, 858 Mini Bionix, Eden Prairie, MN) with a 10 kN load cell.

Force and displacement were recorded throughout the compression and converted to stress and strain based on the initial specimen dimensions. The compressive modulus was analyzed using the TestStar 790.90 mechanical data analysis package designed by MTS and calculated as the slope of the initial linear portion of the stress–strain curve. The offset compressive yield strength was determined as the stress at which the stress–strain curve intersected with a line drawn parallel to the slope defining the modulus, beginning at 1.0% strain.

Maximum Temperature and Setting Time

Maximum temperature and setting time were determined using an adaptation of ASTM F45130 by recording the temperature of the crosslinking mixture (or the PMMA polymerizing mixture) as a function of time after mixing the solid and liquid phase. The mixture was packed into a cylindrical Teflon mold (1 cm diameter × 1 cm height) with a temperature measurement probe connected to a digital multimeter (Datalogging Multimeter, Data Acquisition System ML720, Extech Instruments Corp., MA) positioned in the center of the sample (5 mm from the bottom of the mold). As the highest temperature within each sample is expected to occur at the center of the crosslinking mixture, the probe was placed in the center of the mold to provide a conservative measure of the maximum temperature. The temperature of the mixture was recorded every 1 s until the temperature began to drop. Maximum temperature (Tmax) was defined as the highest temperature attained during crosslinking, and setting time (tset) was determined as the time taken for the mixture to reach the setting temperature (Tset). The following equation was used to calculate the setting temperature:

where Tamb is the recorded ambient temperature.

For each measurement, the temperature change was plotted against time and the average and standard deviation of Tmax and tset for each group were determined from three measurements (n = 3).

Injectability

Injectability was determined by modifying a previously established method 31,32. Briefly, 2 ml of each sample was mixed for 45 s before loading into 10 ml syringes fitted with an 11 gauge needle. Samples were extruded from syringes starting at 2 min after mixing at a crosshead speed of 20 mm/min until the entire sample was extruded (total extrusion time of 36 s) or to a maximum force of 100 N. Force vs. displacement was recorded and data are reported as the volumetric percentage of each sample that was able to be extruded.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between individual groups were determined using one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis via Tukey’s HSD and a significance level of α = 0.05. Main and interaction effects between parameters were analyzed via a linear regression analysis from a previously established method22 using SAS JMP 7.0 software. Differences observed during the main effects analysis were deemed significant if the standard error of the effect did not cross zero.

Results

Compressive Strength and Modulus

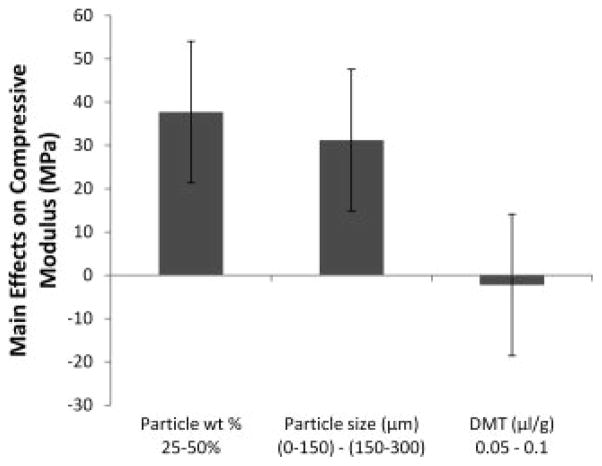

For formulations containing no microparticles (groups A and B), crosslinked specimens exhibited significantly reduced compressive modulus and strength when compared to formulations containing at least 25 wt% particles. When composite formulations contained twice the amount of crosslinked particles (50 wt % vs. 25 wt %), compressive modulus increased by an average of 37.7 ± 16.3 MPa (Figure 1). The compressive modulus also increased when the particle size range was changed from 0–150 μm to 150–300 μm by an average of 31.2 ± 16.3 MPa.

Figure 1.

The main effects of particle weight percentage, particle size, and DMT/PPF ratio on the compressive modulus of crosslinked composites. A positive number indicates that the particular parameter had an increasing effect on the compressive modulus as it was changed from a low level (−) to a high level (+). Error bars represent the standard error of the effect (±16.3 MPa; n = 5).

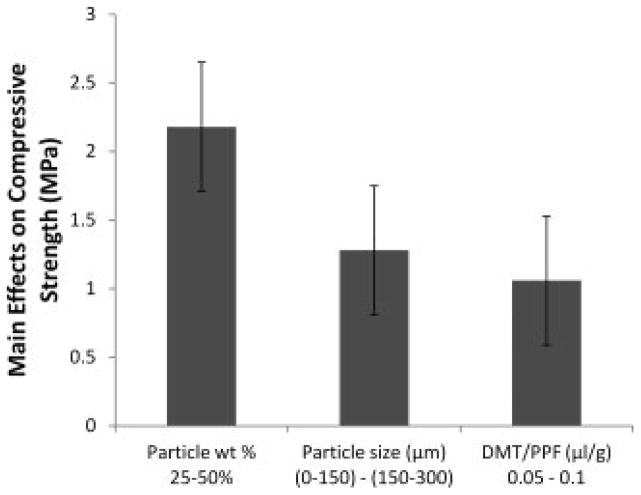

Compressive strength was affected by all three parameters (Figure 2). Specifically, increasing the particle weight percentage, particle size, and DMT concentrations parameters from low to high resulted in increased compressive strength by 2.2 ± 0.5, 1.3 ± 0.5, and 1.1 ± 0.5 MPa, respectively.

Figure 2.

The main effects of particle weight percentage, particle size, and DMT/PPF ratio on the compressive strength of crosslinked composites. A positive number indicates that the particular parameter had an increasing effect on the compressive modulus as it was changed from a low level (−) to a high level (+). Error bars represent the standard error of the effect (±0.5 MPa; n = 5).

Maximum Crosslinking Temperature

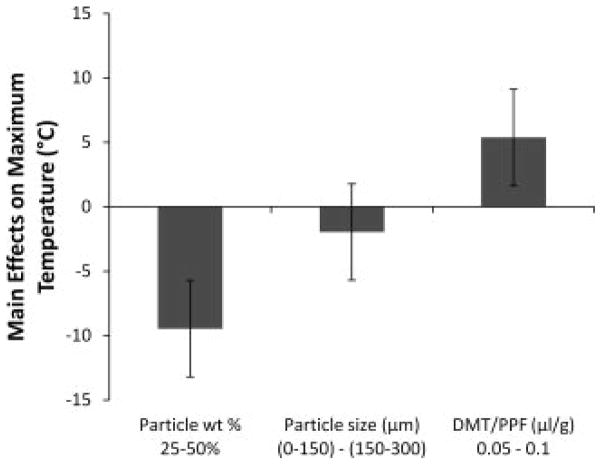

Maximum crosslinking temperature was significantly affected by both particle weight percentage and the DMT concentration (Figure 3). All formulations containing particles exhibited lower crosslinking temperatures than the two formulations without particles, although the difference was not significant for all groups. When particle weight percentage increased from 25 to 50%, the maximum crosslinking temperature significantly decreased by an average of 9.5 ± 3.7 °C. Also, when the concentration of DMT increased from 0.05 to 0.1 μl/g PPF/NVP, the crosslinking temperature significantly increased by an average of 5.4 ± 3.7 °C.

Figure 3.

The main effects of particle weight percentage, particle size, and DMT/PPF ratio on the maximum crosslinking temperature of crosslinking formulations. A positive number indicates that the particular parameter had an increasing effect on the maximum crosslinking temperature as it was changed from a low level (−) to a high level (+). Error bars represent the standard error of the effect (±3.7°C; n = 3).

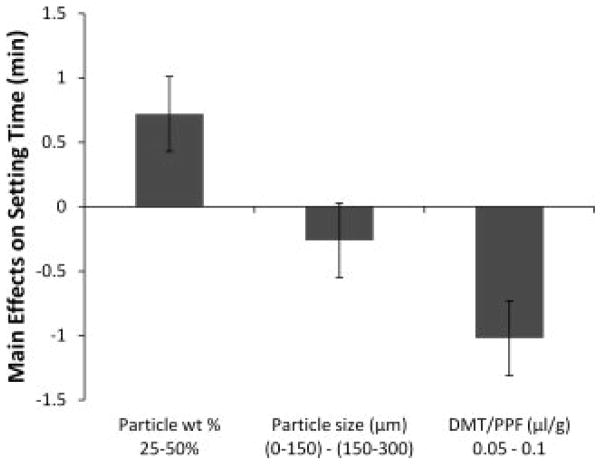

Setting Time

The setting time of formulations was significantly longer for formulations containing the high weight percentage of particles and low concentration of DMT (formulations H and J) (Table 2, Figure 4). When particle weight percentage increased from 25 to 50%, the setting time significantly increased by an average of 0.7 ± 0.3 min. Also, when the concentration of DMT increased from 0.05 to 0.1 μl/g PPF/NVP, the setting time significantly decreased by an average of 1.0 ± 0.3 min.

Table 2.

Summary of Results for Compressive Modulus, Compressive Strength at Yield, Maximum Temperature, Setting Time, and Injectability

| Formulation | Compressive Modulus (MPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Maximum Temperature (°C) | Setting Time (min) | Injectability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 439.2 ± 35.8A | 17.0 ± 1.1A | 100.3 ± 21.6A,B | 2.2 ± 0.8A | 73.4 ± 46.1A,B |

| B | 454.9 ± 53.8A,B | 18.0 ± 1.5A | 102.7 ± 49.3A | 3.0 ± 1.3A | 100 ± 0A |

| C | 772.1 ± 60.7D,E | 29.5 ± 0.8C | 65.3 ± 17.5A,B,C | 2.7 ± 0.3A | 100 ± 0A |

| D | 590.3 ± 51.1B,C | 23.9 ± 0.8B | 38.3 ± 6.8C | 4.3 ± 0.8A,B | 100 ± 0A |

| E | 801.0 ± 71.3E,F | 31.4 ± 0.7D,E | 49.7 ± 4.6B,C | 2.5 ± 0.1A | 96.0 ± 6.9A |

| F | 633.4 ± 53.7C,D | 23.0 ± 1.4B | 35.7 ± 3.5C | 3.5 ± 0.6A | 100 ± 0A |

| G | 638.6 ± 61.3C,D | 27.1 ± 2.9C,D | 27.7 ± 2.5C | 3.6 ± 1.1A | 100 ± 0A |

| H | 821.7 ± 60.7E,F | 30.9 ± 2.1D | 27.7 ± 0.6C | 6.4 ± 0.3B,C | 100 ± 0A |

| I | 727.1 ± 55.0C,D,E | 32.3 ± 1.9D,E | 30.0 ± 3.0C | 3.1 ± 0.6A | 67.2 ± 6.8A,B |

| J | 911.0 ± 38.8F | 34.4 ± 1.3E | 28.0 ± 2.0C | 5.8 ± 0.8B | 57.2 ± 10.4A,B |

| PMMA | 1733.7 ± 161.1G | 57.6 ± 1.6F | 62.3 ± 6.7A,B,C | 8.1 ± 0.6C | 30.6 ± 23.1B |

Values which do not share the same letter within each column are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

The main effects of particle weight percentage, particle size, and DMT/PPF ratio on the setting time of crosslinking formulations. A positive number indicates that the particular parameter had an increasing effect on the setting time as it was changed from a low level (−) to a high level (+). Error bars represent the standard error of the effect (±0.3 min; n = 3).

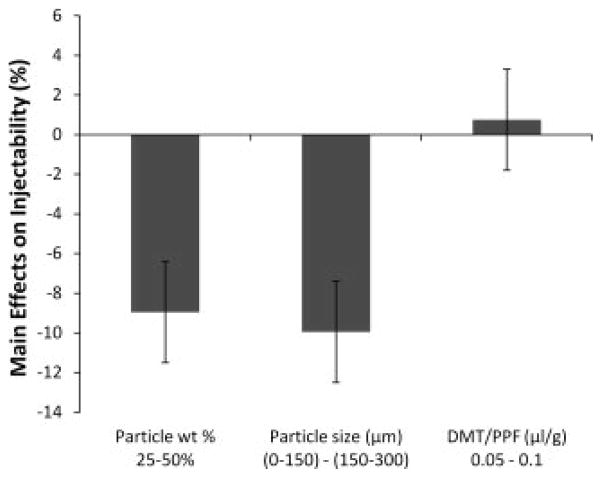

Injectability

The injectability of 6 out of the 10 formulations tested was 100% given the current method (Table 2). Formulations that did not have 100% injectability include groups A and E, which also had the lowest setting times, and groups I and J, which both contained the larger particles in the highest weight percentage (Table 2). Additionally, medium viscosity PMMA bone cement was tested and the injectability was significantly lower than all PPF formulations.

Injectability was significantly affected by particle weight percentage as well as particle size (Figure 5). By increasing particle weight percentage from 25 to 50, the injectability was significantly reduced by 9.0 ± 2.6%. Also, when the size range of included particles was increased from 0–150 to 150–300 μm, the injectability was reduced by 10.0 ± 2.6%.

Figure 5.

The main effects of particle weight percentage, particle size, and DMT/PPF ratio on the injectability of crosslinking formulations. A positive number indicates that the particular parameter had an increasing effect on the compressive modulus as it was changed from a low level (−) to a high level (+). Error bars represent the standard error of the effect (±2.6%; n = 3).

Discussion

This study investigated the formulation of a PPF-based biodegradable bone cement into a two-component system including crosslinked microparticles and evaluated the effects of the formulation on its setting characteristics and the mechanical properties of the crosslinked composites. Overall, the results of this study indicate that the crosslinking temperature of polymer composites composed of PPF can be reduced by the introduction of crosslinked particles without sacrificing other important properties. Additionally, the mechanical and setting properties of those composites can be predictably adjusted by varying several formulation parameters.

One important aspect of the composites in this study is the ability of crosslinking PPF to form a covalent bond with previously crosslinked PPF. In other words, the mechanical stability and ultimate success of the material in question depends on whether or not a liquid matrix of PPF can crosslink to incorporated microparticles and form a covalent network. Previous studies have shown that PPF, even when crosslinked at a high temperature for up to three weeks, still contains unreacted double bonds 33. Therefore, in this study, the unreacted double bonds found on the surface of the crosslinked microparticles can still form bonds with the crosslinking liquid PPF. By SEM image analysis (Figure 7), it appears there is little evidence of any demarcation between the microparticles and the surrounding matrix. Additionally, the mechanical analysis showed that specimens with particles exhibited significantly higher compressive moduli than those without particles, which may reflect that a covalent network was formed between the two forms of PPF. This observed increase in compressive modulus may also be attributed to additional crosslinking of the unreacted double bonds on the surface of the microparticles.

Figure 7.

SEM images of crosslinked and sieved PPF microparticles and composites incorporating those microparticles. A and B show microparticles in the 0–150 μm and 150–300 μm size ranges, respectively. C and D show the surface of crosslinked composites incorporating those microparticles in the 0–150 μm and 150–300 μm size ranges, respectively. E and F show fracture planes of the composites after compressive mechanical testing incorporating microparticles in the 0–150 μm and 150–300 μm size ranges, respectively. Each scale bar represents 500 μm.

Particle size had significant effects on the compressive modulus and strength of crosslinked composites, and injectability of crosslinking formulations. Specifically, increased particle size resulted in an increase in the compressive properties of composites. This finding is in contrast to a previous study conducted using calcium phosphate cements that found that smaller particle sizes resulted in increased compressive strength up to the point where agglomeration occurred 34. Therefore, it may be possible that aggregation of crosslinked PPF microparticles in the smaller size range contributed to the reduction in compressive properties. Additionally, as expected, formulations incorporating the larger particle size range were less injectable, but only when the formulation contained the larger amount of particles (groups I and J). With larger particles at a higher percentage, a phenomenon occurred known as filter pressing, whereby the liquid portion of the mixture is forced through the syringe leaving behind a solid mass of particles 32,35. This problem is typically overcome in other composite formulations by increasing the liquid to powder ratio.

In addition to particle size, the effect of particle weight percentage on construct properties was observed. As particle weight percentage increased from 25 to 50%, the compressive modulus and strength of composites also significantly increased. This is likely due to the fact that the microparticles were fabricated and crosslinked prior to composite formation, and therefore a much more robust crosslinking temperature of 60°C for 24 hours could be used. Higher crosslinking temperatures have previously been shown to increase the crosslinking density of PPF and the resulting compressive mechanical properties 36. Therefore, it is likely the PPF microparticles had a higher compressive modulus and strength than the surrounding PPF matrix, especially given the lower crosslinking temperature of 37°C used for composite formation to simulate conditions expected in the envisioned clinical application. As a result, the composites with a larger amount of microparticles exhibited increased compressive properties.

Increased particle weight percentage also had desirable effects on the maximum crosslinking temperature and setting time of formulations. Predictably, the maximum crosslinking temperature was significantly reduced by increasing particle weight percentage. Because the liquid PPF component of each formulation is the primary contributor to heat production during crosslinking, less heat is produced by formulations that contain smaller amounts of liquid PPF. Also, the microparticles may act as a heat sink during crosslinking, thereby absorbing energy from the crosslinking reaction and further diminishing temperature rise. Finally, increased particle weight percentage also decreased the injectability of crosslinking formulations. As mentioned previously, increasing the ratio of the powder to liquid in the formulations tested caused the syringe to retain the larger particles, thus reducing the overall injectability.

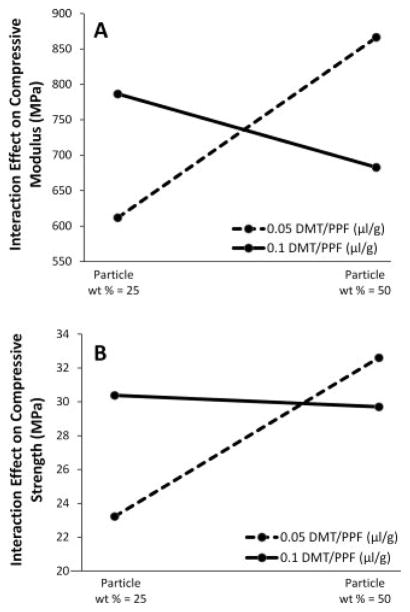

The effects of DMT concentration were also apparent from the data. If one were to isolate DMT concentration and analyze the main effects of this parameter on the compressive modulus, at first glance there appears to be little correlation (Figure 1). However, through analysis of the interaction effects, the data show that DMT concentration and particle weight percentage exhibit a qualitative inverse effect on the compressive modulus and compressive strength (Figure 6). With the lower particle weight percentage of 25%, decreasing DMT concentration decreases compressive modulus and strength of composites. This is an expected result because the function of DMT is to increase the rate of radical formation from the benzoyl peroxide initiator, thereby accelerating the crosslinking reaction and theoretically increasing the crosslinking density of the resulting network. An increase in crosslinking density has previously been shown to increase mechanical properties of crosslinked PPF 36. In contrast, at the highest particle weight percentage of 50%, the data show that mechanical properties are inversely related to DMT concentration (Figure 6). Although counter-intuitive, this response may be due to the fact that much less liquid is present in the mixture, and so the mechanical properties are more affected by the interaction between the crosslinked particles and the liquid matrix, and less so by the final strength of the crosslinked continuous phase. In this case, as the concentration of DMT in the liquid phase is decreased, the crosslinking density of that phase is decreased, the mobility of PPF macromer chains remains high while the network is crosslinking, and thus there exists greater crosslinking interactions between the continuous phase and the particles and the resulting mechanical properties are increased. In contrast, higher DMT concentration leads to increased crosslinking density and reduced chain mobility, thus causing reduced interaction between the continuous phase and the particles and an overall reduction in compressive mechanical properties. Future studies examining the crosslinking density of all formulations would be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Figure 6.

The interaction effects between DMT/PPF ratio and particle weight percentage on the compressive modulus (A) and strength (B) of crosslinked composites. A positive slope line indicates that the compressive property was increased when particle weight percentage was increased from 25% to 50%.

The formulations in this study were also evaluated for their potential in clinical situations. Previous studies evaluating implantable materials in the craniofacial region have used materials with significantly reduced mechanical properties compared to native bone. For example, a clinical study by Bruens et al.27 in 2003 followed 24 patients with various craniofacial conditions and found that PMMA with 50% by volume porosity (compressive modulus and strength of 300 and 10 MPa, respectively26) was sufficient to maintain structural integrity and prevent collapse of the surrounding soft tissue. In this study, the weakest experimental formulation had a compressive modulus and strength of 590 and 23 MPa, respectively, providing a mechanical stability that is more than adequate for this application. Additionally, although the setting times of the experimental formulations in this study were found to be less than that of PMMA, several formulations (H and J) fall within the average setting times of 5–15 minutes obtained for several formulations of PMMA24,25. Therefore, it is possible to obtain clinically relevant setting times by controlling factors such as DMT concentration and particle weight percentage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a two-phase system based on PPF was developed analogous to clinically available PMMA bone cement. Properties such as compressive modulus and strength, maximum setting temperature, setting time and injectability were analyzed and compared to clinically available PMMA. The addition of crosslinked PPF microparticles resulted in reduced crosslinking temperature of formulations to below that of PMMA. Also, it was found that the parameters of this two-phase system including particle weight percentage, particle size, and accelerator concentration were able to significantly influence the properties of crosslinked composites. Overall, the properties of this novel system including mechanical stability, crosslinking temperature and time, and injectability were found to be suitable for craniofacial bone repair applications.

Acknowledgments

Research towards the development of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering was supported by DARPA (W922NF-09-1-0044), NIH (R01-DE017441), and the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine (W81XWH-08-2-0032).

References

- 1.Scheller EL, Krebsbach PH, Kohn DH. Tissue engineering: state of the art in oral rehabilitation. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2009;36(5):368–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01939.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filho RCCA, Oliveira TM, Neto NL, Gurgel C, Abdo RCC. Reconstruction of bony facial contour deficiencies with polymethylmethacrylate implants: case report. Journal of Applied Oral Science. 2011;19(4):426–430. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000400021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotter N, Haisch A, Bucheler M. Cartilage and bone tissue engineering for reconstructive head and neck surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:539–545. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello BJ, Shah G, Kumta P, Sfeir CS. Regenerative medicine for craniomaxillofacial surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2010;22(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker ST, Warnke PH, Behrens E, Wiltfang Morbidity After Iliac Crest Bone Graft Harvesting Over an Anterior Versus Posterior Approach. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;69(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silber J, Anderson G, Daffner S, Brislin B, Leland M, Hilibrand A, Vaccaro A, Albert T. Donor Site Morbidity After Anterior Iliac Crest Bone Harvest for Single-Level Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion. Spine. 2003;28(2):134–139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nocini P, Bedogni A, Valsecchi S, Trevisiol L, Ferrari F, Fior A, Saia G. Fractures of the iliac crest following anterior and posterior bone graft harvesting. Review of the literature and case presentation. Minerva Stomatol. 2003;52(10):448–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollinger J, Brekke J, Gruskin E, Lee D. Role of bone substitutes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;324:55–65. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson IT, Yavuzer R. Hydroxyapatite cement: an alternative for craniofacial skeletal contour refinements. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2000;53(1):24–29. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho YR, Gosain AK. Biomaterials in craniofacial reconstruction. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2004;31(3):377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reckling FWDW. Bone-cement interface temperature during total joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMaio FR. The Science of Bone Cement: A Historical Review. Orthopedics. 2002;25(12 ):1399–1407. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20021201-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedberg EL, Kroese-Deutman HC, Shih CK, Crowther RS, Carney DH, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. In vivo degradation of porous poly(propylene fumarate)/poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid) composite scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26(22):4616–4623. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mistry AS, Pham QP, Schouten C, Yeh T, Christenson EM, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. In vivo bone biocompatibility and degradation of porous fumarate-based polymer/alumoxane nanocomposites for bone tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2010;92A(2):451–462. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmer MD, Ambrose CG, Mikos AG. In vitro degradation of polymeric networks of poly(propylene fumarate) and the crosslinking macromer poly(propylene fumarate)-diacrylate. Biomaterials. 2003;24(4):571–577. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peter SJ, Miller ST, Zhu G, Yasko AW, Mikos AG. In vivo degradation of a poly(propylene fumarate)/beta-tricalcium phosphate injectable composite scaffold. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1998;41(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199807)41:1<1::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher JP, Vehof JWM, Dean D, van der Waerden JPCM, Holland TA, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. Soft and hard tissue response to photocrosslinked poly(propylene fumarate) scaffolds in a rabbit model. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2002;59(3):547–556. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K, Dean D, Mikos AG, Fisher JP. Effect of Initial Cell Seeding Density on Early Osteogenic Signal Expression of Rat Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Cultured on Cross-Linked Poly(propylene fumarate) Disks. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(7):1810–1817. doi: 10.1021/bm900240k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher J, Holland T, Dean D, Engel P, Mikos A. Synthesis and properties of photocross-linked poly(propylene fumarate) scaffolds. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2001;12:673–687. doi: 10.1163/156856201316883476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu T-MG, Warden SJ, Turner CH, Stewart RL. Segmental bone regeneration using a load-bearing biodegradable carrier of bone morphogenetic protein-2. Biomaterials. 2007;28(3):459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henslee AM, Spicer PP, Yoon DM, Nair MB, Meretoja VV, Witherel KE, Jansen JA, Mikos AG, Kasper FK. Biodegradable composite scaffolds incorporating an intramedullary rod and delivering bone morphogenetic protein-2 for stabilization and bone regeneration in segmental long bone defects. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7(10):3627–3637. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peter SJ, Kim P, Yasko AW, Yaszemski MJ, Mikos AG. Crosslinking characteristics of an injectable poly(propylene fumarate)/beta-tricalcium phosphate paste and mechanical properties of the crosslinked composite for use as a biodegradable bone cement. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1999;44(3):314–321. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19990305)44:3<314::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim C, Mahar A, Perry A, Massie J, Lu L, Currier B, Yaszemski M. Biomechanical Evaluation of an Injectable Radiopaque Polypropylene Fumarate Cement for Kyphoplasty in a Cadaveric Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fracture Model. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2007;20(8):604–609. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318040ad73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langdown AJ, Tsai N, Auld J, Walsh WR, Walker P, Bruce WJM. The Influence of Ambient Theater Temperature on Cement Setting Time. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2006;21(3):381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas S, Brauer G, Dickson G. A characterization of polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(3):380–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi M, Kretlow JD, Nguyen A, Young S, Scott Baggett L, Wong ME, Kurtis Kasper F, Mikos AG. Antibiotic-releasing porous polymethylmethacrylate constructs for osseous space maintenance and infection control. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):4146–4156. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruens ML, Pieterman H, Wijn JRd, Vaandrager JM. Porous Polymethylmethacrylate as Bone Substitute in the Craniofacial Area. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14(1):63–68. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shung AK, Timmer MD, Jo S, Engel PS, Mikos AG. Kinetics of poly(propylene fumarate) synthesis by step polymerization of diethyl fumarate and propylene glycol using zinc chloride as a catalyst. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2002;13:95–108. doi: 10.1163/156856202753525963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasper F, Tanahashi K, Fisher J, Mikos A. Synthesis of poly(propylene fumarate) Nat Protoc. 2009;4(4):518–25. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ASTM. Standard Specification for Acrylic Bone Cement. 2008. p. F451. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlad MD, del Valle LJ, Barraco M, Torres R, Lopez J, Fernandez E. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Significantly Enhances the Injectability of Apatitic Bone Cement for Vertebroplasty. Spine. 2008;33(21):2290–2298. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817eccab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khairoun I, Boltong MG, Driessens FCM, Planell JA. Some factors controlling the injectability of calcium phosphate bone cements. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 1998;9(8):425–428. doi: 10.1023/a:1008811215655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timmer MD, Shin H, Horch RA, Ambrose CG, Mikos AG. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Injectable and Biodegradable Poly(propylene fumarate)-Based Networks: Unreacted Macromers, Cross-Linked Networks, and Degradation Products. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4(4):1026–1033. doi: 10.1021/bm0300150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jack V, Buchanan FJ, Dunne NJ. Particle attrition of alpha-tricalcium phosphate: effect on mechanical, handling, and injectability properties of calcium phosphate cements. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 2008;222(H1):19–28. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gbureck U, Barralet JE, Spatz K, Grover LM, Thull R. Ionic modification of calcium phosphate cement viscosity. Part I: hypodermic injection and strength improvement of apatite cement. Biomaterials. 2004;25(11):2187–2195. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timmer MD, Ambrose CG, Mikos AG. Evaluation of thermal- and photo-crosslinked biodegradable poly(propylene fumarate)-based networks. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2003;66A(4):811–818. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]