Abstract

PURPOSE

To estimate the incidence of cataract surgery in a defined population and to determine longitudinal cataract surgery patterns.

SETTING

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

DESIGN

Cohort study.

METHODS

Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) databases were used to identify all incident cataract surgeries in Olmsted County, Minnesota, between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2011. Age-specific and sex-specific incidence rates were calculated and adjusted to the 2010 United States white population. Data were merged with previous REP data (1980 to 2004) to assess temporal trends in cataract surgery. Change in the incidence over time was assessed by fitting generalized linear models assuming a Poisson error structure. The probability of second-eye cataract surgery was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS

Included were 8012 cataract surgeries from 2005 through 2011. During this time, incident cataract surgery significantly increased (P < .001), peaking in 2011 with a rate of 1100 per 100 000 (95% confidence interval, 1050–1160). The probability of second-eye surgery 3, 12, and 24 months after first-eye surgery was 60%, 76%, and 86%, respectively, a significant increase compared with the same intervals in the previous 7 years (1998 to 2004) (P < .001). When merged with 1980 to 2004 REP data, incident cataract surgery steadily increased over the past 3 decades (P < .001).

CONCLUSION

Incident cataract surgery steadily increased over the past 32 years and has not leveled off, as reported in Swedish population-based series. Second-eye surgery was performed sooner and more frequently, with 60% of residents having second-eye surgery within 3-months of first-eye surgery.

Age-related cataract affects more than 22 million people in the United States, with direct medical costs for cataract treatment estimated at $6.8 billion annually.1 It is estimated that the number of persons with cataract will rise to 30 million by 2020.2 The resultant cataract treatment burden will likely influence the distribution of future U.S. health care funding. Understanding temporal cataract surgery rates and factors that influence these rates will better allow us to develop effective policies and procedures to manage costs and to ensure access to appropriate care.

In the U.S., limited population-based cross-sectional or annual rates of incident cataract surgery are available.3–6 Few data on longitudinal cataract surgery rates exist.7–11 Much of the U.S. data are nearly a decade old, lack historical depth, and are limited to the Medicare population. In contrast, population-based cataract surgery databases outside the U.S. are more common.11–17

Population-based incidence data for cataract surgery is advantageous over cross-sectional prevalence data in that it more accurately estimates changes in annual demand. The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a rare example of a population-based medical record linkage system in the U.S. that has almost a half a century of activity. The REP databases record virtually all patient–physician encounters within a stable well-defined geographic area for which the REP has complete data capture. The usefulness of the REP in providing accurate long-term population-based studies of disease incidence is well established.18–20

In this population-based study, we determined the incident cataract surgery rates in the 7-year period from January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2011, in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and merged the data with earlier observations over the previous 25 years,8–10 thereby allowing collection of long-term longitudinal cataract surgery patterns and factors that influence cataract surgery incidence rates.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Sources

Data were obtained using the resources of the REP, a medical records linkage system that has linked and archived the medical records, medical diagnoses, surgical interventions, and demographic information of virtually all persons residing in Olmsted County, Minnesota, for more 40 years.18,20,21 Compared with the entire U.S. population, the county is less ethnically diverse (72.4% versus 85.7% white), more educated (85% versus 94% high school graduates), and wealthier ($51 914 versus $64 090 median household income; 2010 U.S. census data).However, the characteristics of the population are very similar to the populations of Minnesota and the Upper Midwest.22 Only a small proportion of the population (approximately 2%) does not allow any of their medical records to be used for research.22

Health care institutions in the REP provide virtually all medical care for this relatively isolated semi-urban county (2010 total county population, 144 248) and include the Mayo Clinic and its 2 affiliated hospitals, Olmsted Medical Center and its affiliated hospital, and the Rochester Family Medicine Clinic. To enumerate the population, the medical records are linked across different health care providers to create a list of unique subjects. Then, residency criteria and imputations are applied to describe the residency status of residents over time. As a result, the REP provides a data-retrieval system for a complete description of virtually all sources of medical care used by the Olmsted County population over time.18,20–22

Cataract Surgery Cohort

With approval from the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center institutional review boards, all incident primary cataract surgeries performed on Olmsted County residents during the 7-year period between January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2011, were retrospectively identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, ICD-9 procedure codes and Current Procedural Terminology, CPT Procedure codes. Included were cataract extractions performed by phacoemulsification, extracapsular cataract extraction, intracapsular cataract extraction, lens aspiration, and pars plana lensectomy as a primary procedure or as a combined procedure with penetrating keratoplasty, trabeculectomy, or glaucoma shunt procedure. Pars plana lensectomy when combined with a vitreoretinal procedure to improve surgical visualization and cataract extraction in the surgical management of ocular trauma were excluded. Olmsted County residence at the time of surgery was verified using previously validated procedures.18,20,21 A previous REP record review verified case over-ascertainment of less than 1%.23

During the study period, 13 ophthalmologists were available to provide cataract surgery to county residents, as well as regional, national, and international patients. Cataract surgery referrals were from county ophthalmologists, optometrists, and nonophthalmology physician colleagues. Surgeons had varying levels of experience ranging from beginning surgeons in an ophthalmology residency program to surgeons practicing more than 25 years and performing more than 500 cataract surgeries annually. There were no changes in reimbursement rules during the study period.

Data Collection and Analysis

In all identified cohort cases, REP databases provided sex, operated eye, date of birth, and date and type of cataract extraction. The medical records of all identified cohort cases that were not coded as phacoemulsification were manually reviewed to confirm the accuracy of coding.

Annual incidence rates for each sex and age groups were calculated by dividing the number of cataract surgery cases by REP census population estimates. The REP census data provide a validated, virtually complete enumeration of the Olmsted County population at any point in time.18,20,21,24,25 Estimates from the State of Minnesota Demographers Office were used to aid with linear interpolation between census years. Incidence rates were age-adjusted and sex-adjusted to the population structure of the 2010 U.S. white population to allow comparison of this data to data from other populations that may have different age and sex distributions.

The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the rates were calculated assuming Poisson error distribution. The relation of cataract surgery incidence rates to age and time of surgery was assessed by fitting generalized linear models assuming a Poisson error structure. The cumulative probability of second-eye cataract surgery was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The comparison of the curves between time periods was completed using a log-rank test.

RESULTS

During the study period 2005 through 2011, 8012 incident cases of cataract surgery in 5725 Olmsted County residents were identified. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical data. The mean age at cataract surgery was 73 years ± 11 (SD) (range 4 weeks to 100 years), with 1552 cataract surgeries (19%) performed in residents younger than 65 years.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the REP cataract surgery cohort, 2005 through 2011 (N = 8012).

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Cataract extraction technique | |

| Phacoemulsification | 7971 (99.5) |

| ECCE | 34 (0.4) |

| ICCE | 1 (0.0) |

| Aspiration or lensectomy | 6 (0.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3209 (40) |

| Female | 4803 (60) |

| Age at cataract extraction (y) | |

| 0–9 | 18 (0.2) |

| 10–19 | 8 (0.1) |

| 20–29 | 14 (0.2) |

| 30–39 | 39 (0.5) |

| 40–49 | 187 (2.3) |

| 50–59 | 661 (8.2) |

| 60–69 | 1743 (21.8) |

| 70–79 | 3131 (39.1) |

| 80–89 | 2008 (25.1) |

| ≥90 | 203 (2.5) |

ECCE = extracapsular cataract extraction; ICCE = intracapsular cataract extraction

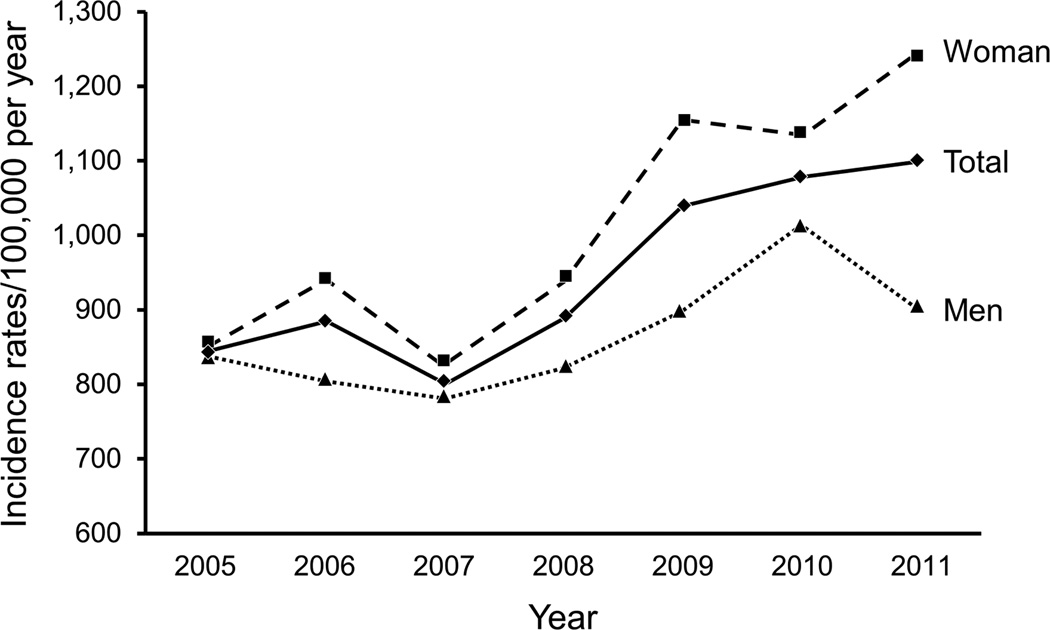

Figure 1 shows age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of cataract surgery during the study period (2005 through 2011). During this time, the overall cataract surgery incidence, age-adjusted and sex-adjusted to the U.S. white population in 2010, was 950 per 100 000 (95% CI, 930–970). The mean annual rate for women was 1020 per 100 000 (95% CI, 990–1050) and was significantly higher than for men (870 per 100 000) (95% CI, 840–900; P < .001). Incident cataract surgery increased substantially during the 7-year study period (P < .001), reaching a peak overall incidence of 1100 per 100 000 (95% CI, 1050–1160) in 2011.

Figure 1.

Overall and sex-specific incidence of cataract surgery among all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2005 through 2011, by year.

The overall rate at which incident cataract surgery increased in 2005 through 2011 was unchanged compared with the previous 7-year period, 1998 through 2004 (P = .10). There was, however, a sex-specific difference. The rate at which cataract surgery increased in women was significantly higher in 2005 through 2011 than in 1998 through 2004 (P = .01), whereas no significant difference was found in men (P = .73) (Figure 1).

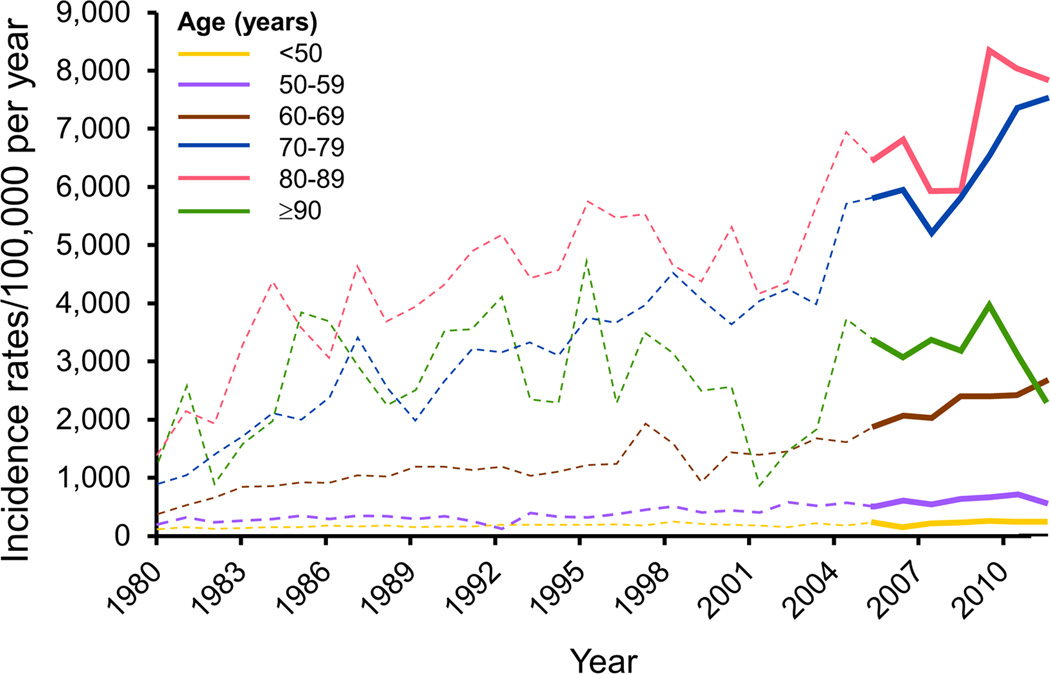

Figure 2 shows the age-specific incidence of cataract surgery from 2005 through 2011, and merged with previous REP data from 1980 through 2004. During the 2005 through 2011 study period, the mean incident cataract surgery was highest in persons 80 to 89 years of age (6940 per 100 000 [95% CI, 6630–7510]), and this group also showed the highest cataract surgery incidence rate over the extended period, 1980 through 2004. There was a significant increase in incident cataract surgery over the 32-year study period in the age groups younger than 50 years, 50 to 59 years, 60 to 69 years, 70 to 79 years, and 80 to 89 years from 1980 through 2011 (all P < .001). There was no significant increase over time in the age group 90 years and older (P = .08).

Figure 2.

Age-specific incidence of cataract surgery among all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 through 2011, by year. Solid lines represent 2005 through 2011, and dashed lines represent 1980 through 2004.8,10

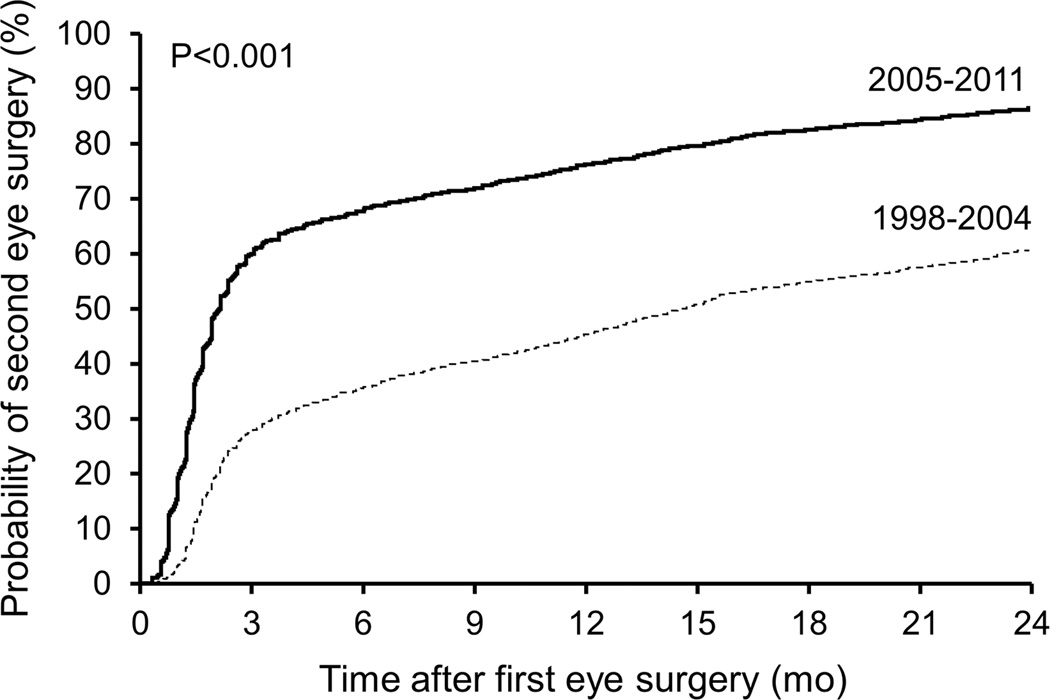

Figure 3 is a Kaplan-Meier plot showing the probability of second-eye cataract surgery. During the 7-year study period (2005 through 2011), the probability of second-eye cataract surgery 3 months, 12 months, and 24 months after first-eye surgery was 60%, 76%, and 86%, respectively. In contrast, in the previous 7-year period (1998 through 2004), the probability of second-eye surgery 3 months, 12 months, and 24 months after first-eye surgery was significantly less at 28%, 45%, and 60%, respectively (all P < .001).

Figure 3.

Cumulative probability of second-eye cataract surgery in all Olmsted County residents between 2005 and 2011 (solid line) versus the probability of second-eye cataract surgery between 1998 and 2004 (dashed line, P < .001; Kaplan-Meier analysis).

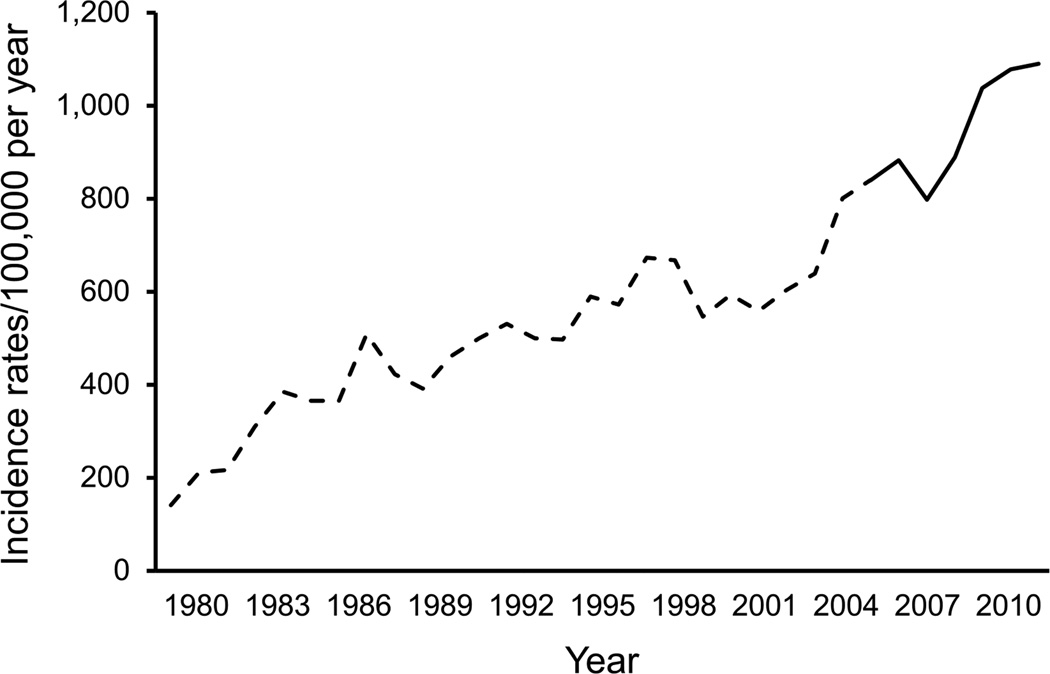

Current data were merged with previous REP data (1980 through 2004) to create a 32-year population-based longitudinal cataract surgery registry (Figure 4). In this extended study, cataract surgery was higher in women (P < .001) and increased with age (P < .001) and the overall incident cataract surgery rates continued to steadily increase (P < .001) with no indication of leveling off.

Figure 4.

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of cataract surgery among all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 through 2011, by year. The solid line represents 2005 through 2011, and the dashed line represents 1980 through 2004.8,10 The incidence of cataract surgery in Olmsted County has steadily increased over the past 3 decades with no indication of leveling off. Second-eye surgery is increasing in frequency.

DISCUSSION

Incident cataract surgery steadily increased during the study period of 2005 through 2011, reaching a peak rate of 1100 per 100 000 residents in 2011, the highest rate recorded in our population over the past 32 years. Merging the current incidence data with previously published data from 1980 through 2004 provides more than 3 decades of continuous population-based information on temporal cataract surgery incident rates in the U.S. During the past 32 years, incident cataract surgery continued to steadily increase in our population base, with no indication of leveling off, as reported in large population-based studies in Sweden.12,16

There are few previous estimates of the incidence of cataract surgery in the U.S.,5,7,8,10,11 and some data are more than a decade old.5,10,11 More recently, Williams et al.,7 in a national self-reported cataract surgery survey of 8670 person 69 years or older, found an annual cataract surgery incidence of 5.3% between 1995 and 2002. Comparable REP data for persons older than 65 years during the same time period would have found an annual cataract surgery incidence of 4.5%. Schein et al.,3 using a 100% sample of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older, report a national cataract surgery incidence of 61.8 per 1000 persons in 2003 to 2004. During the same period, our REP data showed a lower incidence of 46.2 per 1000 residents aged 65 years and older. This difference may be, in part, because Medicare procedure codes will overestimate procedure frequency when a second physician provider uses the same code for support services or when the code is used for comanagement of patients.5,9

Medicare databases are very valuable because they are large and racially and geographically diverse.3,4,6 However, these databases are limited to the U.S. population 65 years and older. Thus, Medicare databases miss many younger patients who have cataract surgery. In our study, Medicare databases would have missed 19% of cataract surgeries performed on county residents younger than 65 years. Although not applicable to our population, Medicare databases also exclude patients in Medicare health maintenance organizations, which comprise approximately 15% of all Medicare beneficiaries.

Population-based estimates of incident cataract surgery are more common in other developed countries.12–17 The Swedish National Cataract Register (SNCR) contains incidence data on more than 1 million cataract surgeries and comprises more than 95% of surgeries performed in Sweden.12 Until 2002, REP cataract surgery incidence data8,10 nicely paralleled incidence data in the SNCR. In 2002, the SNCR documented a leveling off of incident cataract surgery to between 8000 and 9000 procedures per million, and the rate has remained stable up to 2009. In contrast, REP incident cataract surgery continued to steadily increase after 2002 at a rate of growth unchanged from previous years and has reached higher surgical rates (11 000 procedures per 1 million in 2011) than reported in the SNCR.

In recent surveys, the frequency of second-eye surgery has increased and now accounts for 35% to 40% of all cataract operations.3,8,12,26,27 Bilateral cataract surgery has been shown to be cost effective28 and to improve patient satisfaction27,29,30 compared with unilateral cataract surgery. Disturbed motion perception, disturbed stereoacuity, and disturbances from anisometropia are reported disabilities perceived by patients after unilateral cataract surgery or with a cataract in the fellow eye after first-eye surgery.31–33 In addition, second-eye surgery improves mobility orientation and aids in avoiding falls.34 The patient’s perception of disability and visual functioning is an important factor in a surgeon’s final decision making on whether second-eye cataract surgery should be performed.

In our population, there has been a shift to earlier and more frequent second-eye surgery, perhaps due to these documented benefits. In the current 7-year study period, the rate of second-eye surgery 3-months after first-eye surgery more than doubled compared with the previous 7-year period (60% versus 28%) (P < .001). In addition, the rate of second-eye surgery 12 months and 24 months after first-eye surgery (76% and 86%, respectively) was significantly increased over the same time intervals (45% and 60%, respectively) in the previous 7-year period (1998 through 2004) (P < .001).

Consistent with other studies, persons in the ninth decade of life have the highest incidence of cataract surgery,7,10,11 likely due to the slowly progressive and age-related nature of cataracts. This trend likely does not continue for persons in their 90s because many individuals in this group have already had cataract surgery or may be deemed poor surgical candidates.31 Similar to previous studies,3,7,10–12 our study showed a consistently higher incidence of cataract surgery among women throughout the past 32 years. In the past 7 years, there has been a significant acceleration in the rate of cataract surgery in women, but not in men.

It is important for future planning of cataract treatment to understand the reasons for rising cataract surgery rates. First, surgical rates increase when access to surgery is improved for patients with new cataract and those with previously unmet needs. Over the past decade, the number of cataract surgeons in Olmsted County increased 27% and an outpatient surgery center was opened in the community. Higher cataract surgical rates have been correlated with the use of outpatient surgical centers compared with hospital-based surgery among Medicare beneficiaries.3 Second, cataract surgery rates increase when widening indications for surgery are adopted because this creates a larger surgery population and an increase in second-eye surgery. Although second-eye surgery is associated with higher patient satisfaction and improved quality of life,26 earlier second-eye surgery is also associated with increased surgery rates.3

Strengths of the REP include the ability to perform accurate long-term population-based studies within a stable well-defined geographic area for which the REP has complete data capture. Incorrect inclusion within our cataract surgery cohort is estimated at less than 1%.23 Virtually all county residents have surgery at sites for which REP has complete data capture.23 Complete and long-term follow-up is possible because 90% of older adults are seen at least once at REP sites within a 1-year period.22 In addition, the median number of years encompassed by the combined medical records for county residents 60 years of age and older ranges from 41 to 51 years. The REP avoids patient inclusion bias and recall bias, which are common confounders in series that are not population based. Finally, REP databases are inclusive of all ages, which is not possible using Medicare beneficiary data.18,20,21

We acknowledge limitations of the REP with regard to diversity and geography. Although the age, sex, and ethnic characteristics of Olmsted County residents are similar those in the state of Minnesota and the Upper Midwest, Olmsted County residents are less ethnically diverse, more highly educated, and wealthier than the overall U.S. population.18,20 As a consequence, judgment is necessary when generalizing to other populations. Blacks, for example, are underrepresented in Olmsted County and have a lower rate of cataract surgery than whites among Medicare beneficiaries.3,7 Northern U.S. latitudes, such as Olmsted County, also have lower cataract surgery rates than southern latitudes.6 Results in numerous previous studies in Olmsted County, however, have generally been consistent with national data where available.35–38 In addition, no single community in the U.S. is completely representative of the entire U.S. and no specific geographic unit can claim a superior level of representativeness.39,40

In summary, incident cataract surgery has steadily increased in our population over the past 3 decades, with no indication of leveling off as reported in large population-based series in Sweden. Second-eye surgery is performed sooner and more frequently than in the past, with 60% and 86% of residents having second-eye surgery within 3 month and 24 months of first-eye surgery. Our updated incidence data estimates changes in annual demand for cataract surgery and should prove useful in planning future health care spending and in ensuring adequate access to appropriate cataract treatment.

WHAT WAS KNOWN

Large, population-based series in Sweden suggest that incidence of cataract surgery is leveling off. In the U.S., longitudinal population-based cataract surgery databases are limited.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

Over the last 3 decades, incident cataract surgery has steadily increased in this defined U.S. population base, reaching an all-time high in 2011. There is no indication that incident cataract surgery is leveling off.

Second-eye surgery is performed sooner and more frequently. In the study period, 60% of residents had second-eye surgery within 3 months of first-eye surgery, and this was double the rate compared with that in the previous 7-year period.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Research to Prevent Blindness Inc., New York, New York, and the Mayo Foundation (Robert R. Waller Career Development Award), Rochester, Minnesota, USA. Study data were obtained from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland USA under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the ASCRS Symposium on Cataract, IOL and Refractive Surgery, San Francisco, California, USA, April 2013.

Financial Disclosure: No author has a financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vision Problems in the U.S. Prevalence of Adult Vision Impairment and Age- Related Eye Disease in America. Chicago, IL: Prevent Blindness America; Bethesda, MD: National Eye Institute; 2008. [Accessed April 2, 2013]. Available at: http://www.preventblindness.net/site/DocServer/VPUS_2008_update.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of cataract and pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 122:487–494. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.487. Available at: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/OPHTH/9922/EEB30088.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schein OD, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Gower EW. Cataract surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:257–264. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2012.698692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldzweig CL, Mittman BS, Carter GM, Donyo T, Brook RH, Lee P, Mangione CM. Variations in cataract extraction rates in Medicare prepaid and fee-for-service settings. JAMA. 1997;277:1765–1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellwein LB, Friedlin V, McBean AM, Lee PP. Use of eye care services among the 1991 Medicare population. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1732–1743. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javitt JC, Kendix M, Tielsch JM, Steinwachs DM, Schein OD, Kolb MM, Steinberg EP. Geographic variation in utilization of cataract surgery. Med Care. 1995;33:90–105. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams A, Sloan FA, Lee PP. Longitudinal rates of cataract surgery. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 124:1308–1314. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.9.1308. Available at: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/OPHTH/9961/ESE60003.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erie JC, Baratz KH, Hodge DO, Schleck CD, Burke JP. Incidence of cataract surgery from 1980 through 2004: 25-year population-based study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellwein LB, Urato CJ. Use of eye care and associated charges among the Medicare population; 1991–1998. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Arch Ophthalmol. 2002 120:804–811. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.804. Available at: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/OPHTH/6800/ESE10008.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baratz KH, Gray DT, Hodge DO, Butterfield LC, Ilstrup DM. Cataract extraction rates in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 through 1994. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1441–1446. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160611015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein BEK, Klein R, Moss SE. Incidence of cataract surgery; the Beaver Dam Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behndig A, Montan P, Stenevi U, Kugelberg M, Lundström M. One million cataract surgeries: Swedish National Cataract Register 1992–2009. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1539–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarty CA, Mukesh BN, Dimitrov PN, Taylor HR. Incidence and progression of cataract in the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01844-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semmens JB, Li J, Morlet N, Ng J. Trends in cataract surgery and postoperative endophthalmitis in Western Australia (1980–1998): the Endophthalmitis Population Study of Western Australia. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;31:213–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panchapakesan J, Mitchell P, Tumuluri K, Rochtchina E, Foran S, Cumming RG. Five year incidence of cataract surgery: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 87:168–172. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.2.168. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1771515/pdf/bjo08700168.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundström M, Stenevi U, Thorburn W. The Swedish National Cataract Register: a 9-year review. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002 80:248–257. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800304.x. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/118927388/PDFSTART. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundström M, Stenevi U, Thorburn W. Gender and cataract surgery in Sweden 1992–1997; a retrospective observational study based on the Swedish National Cataract Register. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999 77:204–208. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770218.x. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770218.x/pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibsen CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, III, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 87:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3538404/pdf/main.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, III, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Am J Epidemiol. 2011 173:1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. Available at: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/173/9/1059.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, III, Pankratz JJ, Brue SM, Rocca WA. Data Resource Profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1614–1624. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray DT, Hodge DO, Ilstrup DM, Butterfield LC, Baratz KH. Concordance of medicare data and population-based clinical data on cataract surgery utilization in Olmsted County, Minnesota. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Am J Epidemiol. 1997 145:1123–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009075. Available at: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/145/12/1123.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beebe TJ, Ziegenfuss JY, St. Sauver JL, Jenkins SM, Haas L, Davern ME, Talley NJ. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization and survey nonresponse bias. Med Care. 2011;49:365–370. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202ada0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKibben JN, Faust KA. Population distribution—classification of residence. In: Siegel JS, Swanson DA, editors. The Methods and Materials of Demography. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundström M, Stenevi U, Thorburn W. Quality of life after first and second-eye cataract surgery; five-year data collected by the Swedish National Cataract Register. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:1553–1559. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)00984-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai P, Reidy A, Minassian DC. Profile of patients presenting for cataract surgery in the UK: national data collection. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Br J Ophthalmol. 1999 83:893–896. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.8.893. Available at: http://bjo.bmj.com/content/83/8/893.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busbee BG, Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma Cost-utility analysis of cataract surgery in the second eye. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2310–2317. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00796-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan ACS, Tay WT, Zheng YF, Tan AG, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Wong TY, Lamoureux EL. The impact of bilateral or unilateral cataract surgery on visual functioning: when does second eye cataract surgery benefit patients? Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:846–851. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laidlaw DAH, Harrad RA, Hopper CD, Whitaker A, Donovan JL, Brookes ST, Marsh GW, Peters TJ, Sparrow JM, Frankel SJ. Randomised trial of effectiveness of second eye cataract surgery. Lancet. 1998;352:925–929. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)12536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundström M, Albrecht C. Previous cataract surgery in a defined Swedish population. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:50–56. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scotcher SM, Laidlaw DAH, Canning CR, Weal MJ, Harrad RA. Pulfrich’s phenomenon in unilateral cataract. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Br J Ophthalmol. 1997 81:1050–1055. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.12.1050. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1722100/pdf/v081p01050.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talbot EM, Perkins A. The benefit of second eye cataract surgery. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Eye. 1998 12:983–989. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.254. Available at: http://www.nature.com/eye/journal/v12/n6/pdf/eye1998254a.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elliott DB, Patla AE, Furniss M, Adkin A. Improvements in clinical and functional vision and quality of life after second eye cataract surgery. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Optom Vis Sci. 2000 77:13–24. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200001000-00009. Available at: Available at: http://journals.lww.com/optvissci/Fulltext/2000/01000/Improvements_in_Clinical_and_Functional_Vision_and.9.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melton LJ, III, Kearns AE, Atkinson EJ, Bolander ME, Achenbach SJ, Huddleston JM, Therneau TM, Leibson CL. Secular trends in hip fracture incidence and recurrence. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Osteoporos Int. 2009 20:687–694. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0742-8. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2664856/pdf/nihms-75081.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Bailey KR, Kottke TE, Frye RL. Trends in heart disease deaths in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979–1994. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:651–657. doi: 10.4065/74.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ballard-Barbash R, Griffin MR, Wold LE, O’Fallon WM. Breast cancer in residents of Rochester, Minnesota: incidence and survival, 1935 to 1982. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:192–198. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Melton LJ., III Incidence of multiple myeloma in Olmsted County, Minnesota: trends over 6 decades. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Cancer. 2004 101:2667–2674. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20652. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.20652/pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson DW, Mantel N. On epidemiologic surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:613–619. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deming WF. On the use of judgment samples. [Accessed April 2, 2013];Rep Stat Appl. 1976 23:25–31. Available at: http://converge.sharepointsite.net/DemingProject/Shared%20Documents/Scanned%20Papers/On%20the%20Use%20of%20Judgement-Samples.pdf. [Google Scholar]