Abstract

Childhood maltreatment has been linked to numerous negative health outcomes. However, few studies have examined mediating processes using longitudinal designs or objectively measured biological data. This study sought to determine whether child abuse and neglect predicts allostatic load (a composite indicator of accumulated stress-induced biological risk) and to examine potential mediators. Using a prospective cohort design, children (ages 0-11) with documented cases of abuse and neglect were matched with non-maltreated children and followed up into adulthood with in-person interviews and a medical status exam (mean age 41). Allostatic load was assessed with nine physical health indicators. Child abuse and neglect predicted allostatic load, controlling for age, sex, and race. The direct effect of child abuse and neglect persisted despite the introduction of potential mediators of internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence and social support and risky lifestyle in middle adulthood. These findings reveal the long-term impact of childhood abuse and neglect on physical health over 30 years later.

Child maltreatment represents a serious public health concern in the United States and abroad (Gilbert et al., 2009; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013) and has been related to a number of physical health conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, asthma, heart disease, inflammation, obesity, and poor general health (Chartier, Walker, & Naimark, 2007; Danese, Pariante, Caspi, Taylor, & Poulton, 2007; Flaherty et al., 2006; Wegman & Stetler, 2009; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012). With some exceptions, the existing literature relies heavily on cross-sectional designs that provide support for an association between childhood adversities and health outcomes. However, a review of studies relating childhood trauma and physical disorders among adults in the US (Goodwin & Stein, 2004) concluded that future research needs to include “objectively measured biological data using a longitudinal design”. This study is an attempt to understand how these childhood experiences “get under the skin”.

Prior research has documented the impact of early childhood adversities on health-related outcomes by focusing on disparities in morbidity (Batten, Aslan, Maciejewski, & Mazure, 2004; Shanta, Fairweather, Pearson, Felitti, Anda, & Croft, 2009) and mortality (Howard, Anderson, Russell, Howard, & Burke, 2000). However, there has been increased interest in allostatic load (McEwen, 1998), a construct that refers to the process whereby chronic or recurrent stress leads to cascading, potentially irreversible changes in biological stress-regulatory systems. Over time, the effects of earlier stressors are presumed to lead to individual differences in biological markers of the cumulative effects of stress and in stress-related physical and mental disorders. Exposure to childhood adversities, including childhood abuse and neglect, is thought to produce physical wear and tear on a person’s body that, over the lifetime, is associated with less healthy stress-related biological profiles and trajectories. McEwen and his colleagues (McEwen, 1998; McEwen & Stellar, 1993; Seeman et al., 1997) have argued that allostatic load can be quantified by cataloging specific biomarkers across the major biological regulatory systems, including cardiovascular, metabolic, endocrine, and immune systems. Research has utilized this concept of allostatic load to increase explanatory power in understanding the relationship between specific stressors and physical health (see Szanton, Gill, & Allen, 2005 for a review).

Early abusive or neglectful family environments may affect the development of emotional, behavioral, social, and biological mechanisms that undermine a child’s ability to regulate stress and, in turn, this dysregulation is thought to lead to long-term physical health outcomes. One model (Repetti et al., 2002), proposes that poverty and low family socioeconomic status (SES) place social and financial stresses on the family, creating an adverse family environment for the child. In turn, children exposed to such an environment are believed to be at increased risk of developing deficits in emotion regulation and expression, social competence, and later, engaging in health-threatening behaviors (e.g., substance abuse and promiscuous sexual activity), and eventuating in mental and physical health problems across the lifespan. To the extent that socio-emotional functioning is altered by adverse experiences early in life, these socio-emotional dispositions then are likely to influence how children, adolescents, and adults cope with the ongoing stressful events that they encounter across the life course, ultimately, leading to a greater toll on allostatic load (Lupine, 2006).

This model has been supported by research with the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Lehman, Taylor, Kiefe, & Seeman (2009) found that harsh early family environments were related to chronic negative emotional states, including depression, anxiety, anger expression, and hostility, which in turn predicted baseline diastolic and systolic blood pressure as well as change in systolic blood pressure (components of allostatic load). These chronic negative emotional states have been associated with poor health behavior (Caspi et al., 1997), hypertension (Davidson et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2003), and later health risks, including mortality (Martin et al., 1995). Empirical evidence has also shown that growing up in an adverse family environment leads to reduced psychosocial resources, including social support, and increased health risks (House, Umerson, & Landis, 1988; Kertesz et al., 2007; Seeman, 1996; Taylor, 2010), including metabolic functioning (Lehman, Taylor, Kiefe, & Seeman, 2005). Some studies have examined the impact of childhood maltreatment on allostatic load (Katz, Sprang, and Cooke, 2011; Rogosch, Dackis, & Cicchetti, 2012), finding that exposure to child abuse and neglect is associated with higher levels of allostatic load, reflecting more physiological dysregulation and more risk for physical health problems. Although informative, these studies are predominantly cross-sectional or short-term longitudinal studies, extending only through adolescence. Lacking are studies that address the long-term impact of childhood maltreatment on allostatic load and related health problems in adulthood.

In addition, a separate stream of research has documented associations between childhood abuse and neglect and other outcomes, including increased risk for anxiety and depression (Cohen, Brown, & Smailes, 2001; Gibb, Chelminski, & Zimmerman, 2007; MacMillan et al., 2001), poorer social skills and deficient interactions with peers (Crockenberg & Lourie, 1996; Pettit, Dodge, & Brown, 1988), lower levels of social support (Pepin & Banyard, 2006; Schumm, Briggs-Phillips & Hobfoll, 2006; Sperry & Widom, 2013), and increased likelihood of risky sex behaviors (Widom & Kuhns, 1996; Wilson & Widom, 2008; Wilson & Widom, 2009). Given that these outcomes have also been identified as precursors to physical health problems in adulthood (Taylor et al., 2011), researchers have begun to consider the potential mediating role of social, emotional, and behavioral factors that may explain the link between childhood adversities and poor physical health in adulthood. Although there is evidence that child abuse and neglect is related to individual outcomes, few theoretical models provide a set of hypothesized relationships and pathways that may explain the impact of child maltreatment on long-term outcomes, particularly physical health. The present study seeks to address this gap by examining the impact of abuse and neglect in childhood on allostatic load in middle adulthood, drawing on the work of McEwen, Repetti, Taylor, Seeman, and others. While other research suggests that physiological effects, particularly altered hypothalamic pituitary axis functioning, may impact internalizing and externalizing outcomes (Shenk et al, 2010; DeBellis, 2005), given the constraints of our study, we are not able to test such a hypothesis.

The Present Study

The present research draws on earlier work to speculate on possible mediating pathways from child maltreatment to allostatic load in middle adulthood through deficits in earlier socio-emotional functioning and, thus, represents an examination of the long-term impact of child abuse and neglect on development across the lifespan. Specifically, the present research sought to determine whether child abuse and neglect increases a person’s risk for higher allostatic load in adulthood and to examine potential mechanisms through which child maltreatment (an adverse childhood environment) leads to poor physical health outcomes in adulthood.

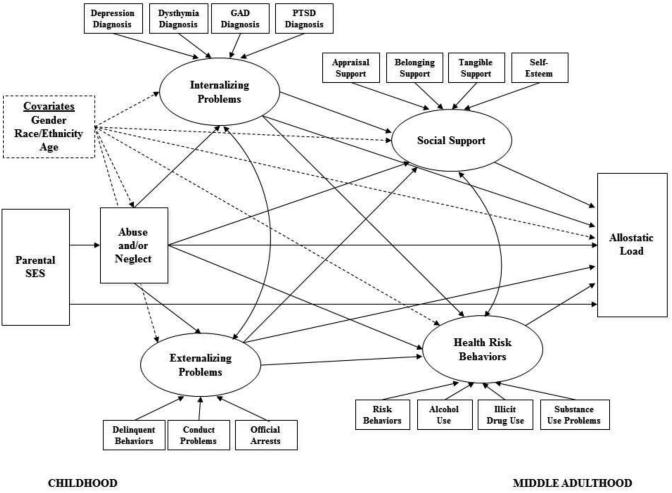

First, we hypothesize that child abuse and neglect will predict higher levels of allostatic load in adulthood. Second, we hypothesize that the impact of childhood abuse and neglect will operate through mediating pathways of high levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescence, leading to later risky health behaviors and lower social support in middle adulthood that in turn, lead to higher allostatic load in later adulthood, when controlling for key demographic characteristics (see Figure 1). Third, in order to determine whether growing up in a low-SES home has an impact on allostatic load -- in the absence of child abuse and neglect, we tested an additional model that assesses the impact of childhood family SES on subsequent potential mediators and allostatic load in adulthood. This model omits child abuse and neglect as a predictor of allostatic load. The issue of family SES is particularly relevant here because the sample studied here is skewed in the direction opposite middle and upper class families. Thus, it is important to recognize that the maltreated children in this study had an additional adversity of being predominantly from lower SES backgrounds and children from lower SES backgrounds are likely to face more health care challenges in general. As described below, matching for social class was an important design criterion of the current study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model Showing All Indicators, Covariates, and Proposed Paths. Covariate paths are indicated by a dotted line.

Method

Design

Data are from a prospective cohort design study (Leventhal, 1982; Schulsinger, Mednick, & Knop, 1981) in which abused and neglected children were matched with non-abused and non-neglected children and followed prospectively into adulthood. Notable features of the design include: (1) an unambiguous operationalization of child abuse and neglect; (2) a prospective design; (3) separate abused and neglected groups; (4) a large sample; (5) a comparison group matched as closely as possible on age, sex, race and approximate social class background; and (6) assessment of the long-term consequences of abuse and neglect beyond adolescence and into adulthood (Widom, 1989a).

The prospective nature of this study disentangles the effects of childhood victimization from other potential confounding effects. Because of the matching procedure, subjects are assumed to differ only in the risk factor: that is, having experienced childhood neglect or sexual or physical abuse. Since it is obviously not possible to randomly assign subjects to groups, the assumption of group equivalency is an approximation. The comparison group may also differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables nested within abuse or neglect.

Participants

The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court substantiated cases of child abuse and neglect were included. Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971 (N = 908). To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality, and to ensure that the temporal sequence was clear (that is, child abuse and neglect → subsequent outcomes), abuse and neglect cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, bone and skull fractures, and other evidence of physical injury. Sexual abuse charges included felony sexual assault, fondling or touching in an obscene manner, rape, sodomy, and incest. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents' deficiencies in childcare were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time. These cases represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children. Although there is considerable discussion in the literature about the extent of overlap among types of child maltreatment, in our sample, only 11% experienced more than one type of maltreatment.

A critical element of this design was the establishment of a comparison or control group, matched as closely as possible on the basis of sex, age, race, and approximate family socio-economic status during the time period under study (1967 through 1971). To accomplish this matching, the sample of abused and neglected cases was first divided into two groups on the basis of their age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Children who were under school age at the time of the abuse or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 1 week), and hospital of birth through the use of county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 6 months), same class in same elementary school during the years 1967 through 1971, and home address, within a five-block radius of the abused or neglected child, if possible. Overall, there were 667 matches (73.7%) for the abused and neglected children.

Matching for social class is important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Conroy et al., 2010; MacMillan et al., 2001; Widom, 1989b). It is difficult to match exactly for social class because higher income families could live in lower social class neighborhoods and vice-versa. The matching procedure used here is based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. Shadish, Cook, & Campbell (2002) recommend using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes, when random sampling is not possible. Busing was not operational at the time, and students in elementary schools in this county were from small, socio-economically homogeneous neighborhoods.

If the control group included subjects who had been officially reported as abused or neglected, this would jeopardize the design of the study. Official records were checked, and any proposed comparison group child who had an official record of childhood abuse or neglect was eliminated. In these cases (n=11), a second matched subject was assigned to the control group to replace the individual excluded. Despite these efforts, it is possible that some members of the control group may have experienced unreported abuse or neglect.

The first phase of this research involved a prospective cohort design and an archival records check to identify a group of abused and neglected children and matched controls (Widom, 1989b). Subsequent phases of the research involved tracing, locating, and interviewing the abused and/or neglected individuals (22-30 years after the initial court cases for the abuse and/or neglect) and the matched comparison group. Follow-up in-person interviews were approximately 2-3 hours long and consisted of standardized tests and measures. Throughout all waves of the study, the interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group, and to the participants’ group membership. Similarly, the participants were blind to the purpose of the study. Participants were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study and subjects who participated signed a consent form acknowledging that they understood the conditions of their participation and that they were participating voluntarily.

In the first follow-up interviews (1989-1995), 1,307 (83%) subjects were located and 1,196 (76%) interviewed. Subsequent follow-up interviews were conducted in 2000-2002 (N = 896) and in 2003-2005, when another follow-up interview and medical status examination were conducted (N = 808).

Initially, the sample was about half male (49.3%) and half female (51.7%) and about two-thirds White (66.2%) and one-third Black (32.6%). Although there has been attrition associated with death, refusals, and our inability to locate individuals over the various study waves, the composition of the sample at the four time points has remained about the same (see Table 1). The abuse and neglect group represented 56-58% at each time period; White, non-Hispanics were 60-66%; and males were 47-51% of the samples. There were no significant differences across the samples by gender, race/ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, or maltreatment status across the waves.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample at Different Waves of Data Collection

| Interview |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | Records 1967-1971 |

1 1989-1995 |

2 2000-2002 |

3 2003-2005 |

| N | 1575 | 1196 | 896 | 808 |

| Sex (% male) | 49.3 | 51.3 | 49.0 | 47.3 |

| White (%) | 66.2 | 62.9 | 62.2 | 60.4 |

| Black (%) | 32.6 | 34.9 | 35.2 | 37.0 |

| Other (%) | 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Hispanic (%) | 0.3 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Ethnicity (% White, non-Hispanic) | 66.2 | 63.8 | 63.4 | 61.8 |

| Abuse/neglect (%) | 57.7 | 56.5 | 55.8 | 56.8 |

| Physical abuse (%) | 10.2 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 9.7 |

| Neglect (%) | 44.3 | 45.4 | 45.3 | 45.9 |

| Sexual abuse (%) | 9.7 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 7.5 |

| Mean age at petition (SD) | 6.4 (3.3) | 6.3 (3.3) | 6.2 (3.3) | 6.3 (3.3) |

| Mean age at interview (SD) | 29.2 (3.8) | 39.5 (3.5) | 41.2 (3.5) | |

The average highest grade of school completed for the sample was 11.47 (SD = 2.19). Occupational status at the time of the first interview was coded according to the Hollingshead Occupational Coding Index (Hollingshead, 1975). Median occupational level of the sample was semi-skilled, and less than 7% of the overall sample was in levels 7-9 (managers through professionals). Thus, the sample overall is heavily dominated by individuals at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum.

Variables and Measures

Information for these analyses is drawn from multiple waves of this study. The identification and selection of the abused and neglected and control groups was undertaken during the first phase of the study (Widom, 1989a). Information about potential mediators was obtained from interviews during 1989-1995 (Mage = 29.2) and 2000-2002 (Mage = 39.5). The physical health outcomes were assessed during 2003-2005 as part of a medical status examination (Mage = 41.2).

Child abuse and neglect

Official reports of child abuse and neglect, based on records of county juvenile (family) and adult criminal courts from 1967-1971, were used to operationalize maltreatment. Only court-substantiated cases involving children under the age of 12 at the time of abuse or neglect were included.

Adolescent internalizing problems

During the first interview, the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-III-R: Robins, Helzer, Cottler, & Goldring, 1989) was used to assess DSM-III-R diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) for major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), dysthymia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Adolescent internalizing disorders were defined as meeting the diagnostic criteria with onset before age 18: 120 (10.1%) participants met diagnostic criteria for MDD, 34 (2.8%) for GAD, 81 (6.8%) for dysthymia, and 164 (13.9%) for PTSD. Of the total sample (N = 1,196), 258 met diagnostic criteria for at least one internalizing disorder. The majority (64.7%) met criteria for one disorder, 20.5% met criteria for two disorders, 13.2% met criteria for three disorders, and 0.2% met criteria for all four disorders. A latent factor was created by combining these four indicators to operationalize adolescent internalizing problems.

Adolescent externalizing problems

Three variables were used to operationalize adolescent externalizing problems: (1) number of self-reported conduct problem symptoms before age 15 (DIS-III-R); (2) number of self-reported delinquent or criminal acts before age 18; and (3) number of official arrests before age 18, excluding status offenses. Participants answered yes or no to each conduct problem symptom and then the total number was summed (range = 0– 9, M = 1.73, SD = 1.85). The number of delinquent acts (range = 0 – 332, M = 10.95, SD = 28.86) was based on information provided in response to 26 questions about crime and delinquency (Wolfgang and Weiner, 1989). Participants were asked whether they had ever (and how many times) engaged in these behaviors before the age of 18. Responses to these items were summed and these scores were transformed by dividing each data point by 10. The third indicator of adolescent externalizing problems was based on the number of arrests as a juvenile (i.e., before age 18) (range = 0 – 16, M = 0.56, SD = 1.45). Arrest information was obtained from official records from two searches of law enforcement (Widom, 1989b; Maxfield & Widom, 1996). We combined these three indicators to create a latent variable reflecting adolescent externalizing problems

Social support

At the second interview, social support was assessed using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; 17 items; Cohen, Mermelstein, Kamarck, & Hoberman, 1985). Four subscales were used: (1) appraisal support (“There are several people that I trust to help solve my problems”); (2) belonging support (“No one I know would throw a birthday party for me”); (3) tangible support (“If I were sick, I could easily find someone to help me with my daily chores”); and (4) self-esteem (“Most people I know think highly of me”). Items for each subscale were summed, with higher scores indicating higher levels of support. Subscales were significantly correlated (r = .34 - .58) and were combined to create a latent variable.

Risky health behaviors

At the second interview, risky behaviors, alcohol and illicit drug use, and problems associated with substance use were assessed. Windle’s (1994) Risky Behavior Assessment Measure was used to assess risky behaviors and lifestyle characteristics. Respondents indicated how often they had engaged in risky behaviors (e.g., “gone to a place that is dangerous”) in the past year. Item scores were recoded to the midpoints of the response categories and then summed to form a single index of risky behavior/lifestyle, as in prior work with this measure (Windle, 1994). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample is .62. Alcohol and illicit drug use were assessed through a series of questions adapted from the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project (Pandina, Labouvie, & White, 1984), designed to elicit information about the quantity and frequency of substance use. Respondents reported the number of days over the past year that they drank an alcoholic beverage, used marijuana, used cocaine, used heroin, and used psychedelics on categorical scales, with responses for each substance ranging from 1 (I didn’t use this substance within the past year) to 10 (More than once a day). For each substance, categorical scores were recoded to represent a continuous variable that reflected the number of days of use within the past year. For drug use, the four separate continuous variables were summed to indicate the total amount of use over the past year. Scores for alcohol use ranged from 0 – 730 (M = 65.04, SD = 126.34) and scores for drug use ranged from 0 – 1095 (M = 35.98, SD = 119.43); however, given the very high standard deviations, these data were transformed by dividing each data point by 10. Substance use problems were assessed on the basis of the number of participants’ positive responses to questions on the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Inventory (White & Labouvie, 1989), adapted to cover drug use problems as well as those associated with alcohol (Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample is .92). Risky behaviors, alcohol and illicit drug use, and problems associated with substance use were combined to create a latent variable of risky health behaviors.

Allostatic load

Physical exam and blood test results were obtained through a medical status exam and venipuncture during 2003-2005 (Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012). A licensed registered nurse performed the medical status examination in the participant’s home or other quiet location of the person’s choosing. The results from blood tests and measurements were used to create a composite variable of nine indicators to operationalize allostatic load: (1) Systolic blood pressure; (2) Diastolic blood pressure; (3) HDL (high density lipoprotein) – molecules that remove cholesterol from the bloodstream and carry to the liver; (4) Total cholesterol to HDL ratio; (5) HbA1c (Hemoglobin A1c) – a measure that reflects the average blood glucose level over a period of months and is related to risk for diabetes; (6) C-reactive protein – a protein that appears in the blood in certain acute inflammatory conditions, associated with risk for arthritis and cardiovascular disease; (7) Albumin - protein found in blood serum, plays a role in transporting amino acids and regulating distribution of water, indicative of nutritional status, including protein deficiency, and liver function; (8) Creatinine clearance - volume of blood plasma cleared of creatinine per unit of time, assesses the excretory function of the kidneys; and (9) Peak air flow - a measure of how well and fast a person can exhale air, commonly used to assess and monitor lung diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or bronchitis, or emphysema. The allostatic load variable is computed by counting the number of indicators (out of the 9 possible) for which the participant’s scores were in the highest risk quartile. Scores on the allostatic load composite, which ranged from 0 (low; fewer health problems) to 7 (high, more health problems) (M = 1.94, SD = 1.61), were comparable to scores reported in other studies using this type of index (Crimmins, Johnston, Hayman, Seeman, 2003; Schulz, Mentz, Lachance, Johnson Gaines, & Israel, 2012).

Despite its wide use and general acceptance in the field, this operationalization of allostatic load as an index computed by summing dichotomous indicators of risk has come under criticism by some researchers (Vie, Hufthammer, Holmen, Meland, & Breidablik, 2014), leading to alternative conceptualizations. Therefore, to ensure that our findings were not unduly influenced by the method of operationalization, an alternative operationalization of allostatic load that has been used in a number of recently published studies (Hill, Rote, Ellison, & Burdette, 2014; Vie et al., 2014) was also created for use here. First raw scores on each of the nine physical health indicators were standardized and outliers winsorized. Next, a mean score across all nine standardized indicators was created for each participant. This alternative allostatic load variable using standardized scores was highly correlated with the original allostatic load variable (r = 0.69, p < .001).

Control variables

Parental socio-economic status (SES) was included as an exogenous latent variable predicting child maltreatment. This composite SES variable was created by standardizing and averaging scores indicating whether: (1) the family received welfare when the participant was a child; (2) the mother and/or father completed high school; (3) either parent had ever been unemployed; and (4) the participant lived in a single-parent household. Participant gender, race (White Non-Hispanic vs. other), and age at the time of the first interview were also included in the model as covariates on all endogenous variables in each model.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analysis and linear regression were used to assess whether child abuse and neglect predicted allostatic load (SPSS version 21). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the fit of the measurement indicators onto the respective latent variables included in the model. Structural equation modeling (SEM) (Mplus 7.0; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) was used to test the models that examined the direct and mediating pathways from child abuse and neglect to allostatic load in middle adulthood (see earlier Figure 1). The first model focused on pathways through adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. A second model was also tested, which included the same variables as the first model (adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems), but omitted child abuse and neglect.

As recommended by Hu and Bentler (1998), multiple fit indices were used to evaluate the overall pattern of fit of the latent variables included in the models, including chi-square (χ2), critical ratio (χ2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI). Based on these indices, an adequate fit is indicated by a critical ratio below 3, RMSEA of .08 or lower (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996), and CFI values of .90 or greater (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Muller, 2003). In addition, individual path coefficients and indirect effects were also examined to assess the fit of each of the measurement and latent variables included in the models. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was utilized with the weighted least square mean- and variance-adjusted estimator to account for missing information and the inevitable attrition across the multiple time points of data within the present study (Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

Results

Simple analyses were conducted to determine whether there was an effect of childhood abuse and neglect on allostatic load in adulthood. The results of these analyses indicate that childhood abuse and neglect predicted allostatic load (t = 3.67, p < .001), controlling for age, sex, and race (β = .12, t = 3.59, p < .001).

Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that all measurement indicators loaded onto the respective latent variables included in the model (see Table 2). This was the case for adolescent internalizing (β =.62 - .88, p < .001) and externalizing problems (β =.35 - .70, p < .001), middle adult social support (β =.56 - .76, p < .001), and middle adult risky health behaviors (β =.34 - .88, p < .001).

Table 2.

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis for all Latent Variables in the Model

| β | χ 2 | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing Problems (before age 18) | 7.60 | 1.09 | -- | -- | -- | |

| Depression | .84*** | |||||

| Anxiety | .73*** | |||||

| Dysthymia | .88*** | |||||

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | .62*** | |||||

| Externalizing Problems | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Conduct problems before 15 | .70*** | |||||

| Delinquent acts before 18 | .35*** | |||||

| Official arrests before 18 | .67*** | |||||

| Social Support | 1.77 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Appraisal Support | .61*** | |||||

| Belonging Support | .76*** | |||||

| Tangible Support | .76*** | |||||

| Self-esteem | .56*** | |||||

| Risky Health Behaviors | 1.07 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | |

| Risky Behavior/Lifestyle | .34*** | |||||

| Alcohol Use | .48*** | |||||

| Drug Use | .44*** | |||||

| Symptoms of Substance Use | .88*** |

Note.

p < .001. RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. CFI = Comparative Fit Index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI values are not reliable for the latent variables involving only categorical indicators, and therefore are not presented for internalizing problems.

Child Abuse and Neglect to Allostatic Load

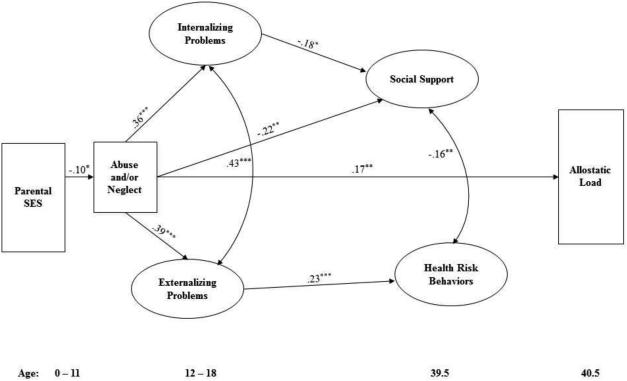

The first structural model assessed the direct relationship from parental SES to allostatic load, the direct relationship between parental SES and child abuse and neglect, the direct relationship between child abuse and neglect and allostatic load, and the indirect relationships among these variables, with mediating paths from child abuse and neglect through adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems and social support and risky behaviors and lifestyle in middle adulthood (see earlier Figure 1). Inspection of the fit indices suggested that this model provided an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 (156) = 448.99, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.90) and explained 8.3% of the variance in allostatic load. However, examination of the path coefficients and indirect effects indicated that the only significant path to allostatic load was the direct path from child abuse and neglect (see Figure 2). Parental SES predicted child abuse and neglect and, in turn, child abuse and neglect predicted all of the mediators with the exception of risky behaviors and lifestyle, but neither parental SES nor the mediators predicted allostatic load.

Figure 2.

Significant paths linking childhood abuse and neglect to allostatic load in middle adulthood. Coefficients are standardized (β). Analyses control for sex, race/ ethnicity, and age. Internalizing and externalizing problems before age 18 were assessed retrospectively at mean age 29. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

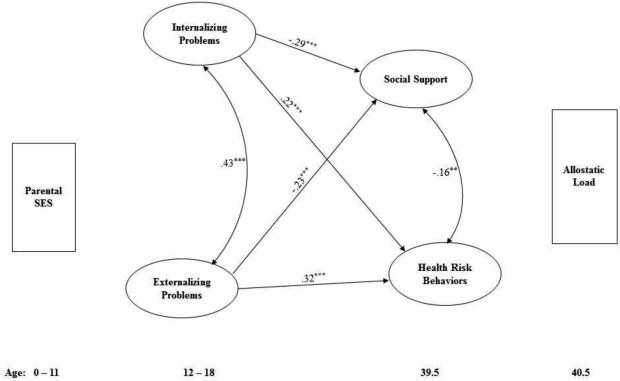

Parental Socio-Economic Status to Allostatic Load

The second model examined the direct and mediating paths from parental SES to allostatic load without child abuse and neglect in the model. This model was included to assess whether the significance of any of the paths to allostatic load would change in an important way if this specific adverse childhood experience was not included in the model. The overall fit of this model was slightly worse than the previous model (χ2 (143) = 492.26, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.87) and explained slightly less of the variance in allostatic load (R2 = .06). There were no direct or indirect paths from parental SES to allostatic load (see Figure 3). In addition, none of the mediators were related to allostatic load in this model.

Figure 3.

Significant paths in the model examining whether parental socio-economic status predicts allostatic load in middle adulthood. Coefficients are standardized (β). Analyses control for sex, race/ethnicity, and age. Internalizing and externalizing problems before age 18 were assessed retrospectively at mean age 29. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

A chi-square difference test was computed to provide an objective assessment of whether the fit of the first model was significantly better than the fit of the second model. Results indicated that the model incorporating both parental SES and child maltreatment provided a significantly better fit than the model with only parental SES (χ2diff = 43.27, dfdiff = 13, p < .001).

To determine that these results were not due to the use of a “highest risk quartile” operationalization of allostatic load, we used an alternative version of allostatic load based on standardized scores and the results were essentially the same. The alternative allostatic load variable showed a strong association with child maltreatment, with higher allostatic load for individuals with histories of abuse and neglect compared to controls (t = 2.20, p < .05), even when controlling for age, sex, and race (B = 0.05, t = 2.05, p < .05). When structural models were re-run using this alternative operationalization, there were no differences in overall fit of the models or in the significance of individual path estimates and indirect effects compared to the models using the original allostatic load variable operationalization.

Discussion

In a 30-year prospective follow-up of a large group of abused and neglected children and matched controls, abuse and neglect in childhood predicted allostatic load in middle adulthood. The two models hypothesized to explain the linkage between this particular childhood adversity (abuse and neglect) and physical health outcomes in adulthood each had acceptable fit indices. In both models, child abuse and neglect predicted most of the hypothesized mediators; surprisingly, however, there were no significant mediating paths from childhood abuse and neglect to allostatic load in adulthood. Child abuse and neglect had the predicted effect on early characteristics (adolescent internalizing and externalizing) and on social support in middle adulthood, but links between these mediators and allostatic load in adulthood were not found.

These findings have important implications for understanding and addressing the long-term impact of childhood maltreatment on physical health in adulthood. Given that child abuse and neglect leads to poorer physical health in adulthood, regardless of intervening characteristics, these new results suggest that secondary intervention efforts that target physical health problems only among those who have been identified as manifesting these socio-emotional problems or risky behaviors in adolescence or young adulthood may not be effective in reducing allostatic load. Instead, these findings reinforce the need to focus on preventive efforts to reduce the incidence of child maltreatment or tertiary intervention efforts to improve physical health among adults with histories of child abuse or neglect.

Although a number of studies have reported an association between lower SES and higher allostatic load both cross-sectionally (Kubzansky, Kawachi, & Sparrow, 1999; Weinstein, Goldman, Hedley, Yu-Hsuan, & Seeman, 2003) and longitudinally (Evans & Kim, 2007; 2012), the present study did not provide support for this link. Lower SES in childhood was not associated with increased allostatic load in middle adulthood, regardless of whether child maltreatment was included in the model. In addition to highlighting the robust impact of child abuse and neglect on physical health in allostatic load, this finding suggests that while SES may have a concurrent impact on physical health, the negative impact of childhood SES may be mitigated by intermediate individual and contextual factors in adolescence and adulthood. It is also possible that the impact of SES was diminished because of reduced variance associated with the predominance of study participants at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum.

These new findings suggest that researchers ought to consider alternative mediators between childhood maltreatment and physical health in adulthood. Although the models tested here were based on potential risk factors that have been hypothesized to explain adult health outcomes for individuals who experienced adversities in childhood, our results did not provide support for their mediating role. However, there are likely to be other unexplored risk and resiliency factors that play key roles in the trajectory from childhood abuse and neglect to adverse physical health outcomes. The variables included in this analysis were adapted from those in the original “risky families” model (Repetti et al., 2002) and later model (Taylor et al., 2011). The current findings suggest that the impact of these mediating variables is greatly reduced for families like those in the present study, with abuse and/or neglect that is serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Alternatively, it is possible that the failure to find support for the indirect effects was due to the difference in operationalization and timing of the mediators. The measurement of these potential mediators at single points in time did not permit us to examine the dynamic nature of these risk factors, which may be particularly salient to understanding adult health outcomes. Other researchers should attempt to replicate these findings with different samples and measures that account for change in individual characteristics over time. Future research should also examine the extent to which there may be gene by environment (childhood abuse and neglect) interactions that influence the pathways hypothesized in these models and risk for higher levels of allostatic load in adulthood.

While this research has numerous strengths, several caveats should be noted. The findings are based on official court cases of childhood abuse and neglect and, thus, are not necessarily generalizable to unreported or unsubstantiated cases of child abuse and neglect. These findings also cannot be generalized to abuse and neglect that occurs in middle- or upper-class children and their families, given that this sample was heavily dominated by individuals at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. The current findings represent the experiences of children growing up in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the Midwestern part of the United States and it is possible that children maltreated at a later time may manifest different consequences. In addition, the use of allostatic load as an index of physical health has been called into question by some researchers, who have noted concerns about the inclusion of different physiological measures within different studies, the determination of the proportion of a sample considered at “high risk”, and whether it is necessary to control for other factors, such as smoking and depression (Szanton et al., 2005).

Despite these limitations, these results demonstrate the long-term impact of child abuse and neglect on fundamental physical health functioning over 30 years later. Given these new findings, future research should examine other potential mediators that play a role in increasing allostatic load among abused and neglected children grown-up and may provide a better understanding of when and how to effectively target poor physical health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD NICHD (HD072581, HD40774), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033 and 89-IJ-CX-0007), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Points of view are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the United States Department of Justice or National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd. Author; Washington, DC: 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53(1):371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Child abuse, adult health, and health care utilization: Results from a representative community sample. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:1031–1038. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E. Child abuse and neglect and the development of mental disorders in the general population. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:981–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research and applications. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; Dordrecht: 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy K, Sandel M, Zuckerman B. Poverty grown up: How childhood socioeconomic status impacts adult health. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31(2):154–160. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c21a1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Lourie A. Parents' conflict strategies with children and children's conflict strategies with peers. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42(4):495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, Anda RF. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: Evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(3):268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8(3):430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty and health cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychological Science. 2007;18(11):953–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty and young adults’ allostatic load: The mediating role of childhood cumulative risk exposure. Psychological Science. 2012;23(9):979–983. doi: 10.1177/0956797612441218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Theodore A, English DJ, Black MM, Dubowitz H. Effect of early childhood adversity on child health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:1232–1238. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and diagnosis of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult psychiatric outpatient. Depression & Anxiety. 2007;24(4):256–263. doi: 10.1002/da.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson RL, Hartshorne TS. Childhood sexual abuse and adult loneliness and network orientation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(11):1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CW, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R, Stein M. Association between childhood trauma and physical disorders among adults in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(3):509–520. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300134x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer AL, Sanderson J, Mertin P. Influence of negative childhood experiences on psychological functioning, social support, and parenting for mothers recovering from addiction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(5):421–433. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Rote SM, Ellison CG, Burdette AM. Religious attendance and biological functioning: A multiple specification approach. Journal of Aging and Health. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0898264314529333. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology. 1988;14(1):293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Katz DA, Sprang G, Cooke C. Allostatic load and child maltreatment in infancy. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10(2):159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz SG, Pletcher MJ, Safford M, Halanych J, Kirk K, Schumacher J, Kiefe CI. Illicit drug use in young adults and subsequent decline in general health: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(2):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman BJ, Taylor SE, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. Relation of childhood socioeconomic status and family environment to adult metabolic functioning in the CARDIA study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(6):846–854. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188443.48405.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman BJ, Taylor SE, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. Relationship of early life stress and psychological functioning to blood pressure in the CARDIA study. Health Psychology. 2009;28(3):338–346. doi: 10.1037/a0013785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM. Research strategies and methodologic standards in studies of risk factors for child abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1982;6:113–123. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(82)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle M, Jamieson E, Beardslee WR. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: Revisited six years later. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;840(1):33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7th Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pandina RJ, Labouvie EW, White HR. Potential contributions of the life span developmental approach to the study of adolescent alcohol and drug use: The Rutgers Health and Human Development Project, a working model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1984;14(2):253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pepin EN, Banyard VL. Social support: A mediator between child maltreatment and developmental outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(4):612–625. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Brown MM. Early family experience, social problem solving patterns, and children's social competence. Child Development. 1988;59(1):107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Helzer JE, Cottler L, Goldring E. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III-A. Washington University; St Louis, MO: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Muller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research. 2003;8(2):23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Schulsinger F, Mednick SA, Knop J. Longitudinal research: Methods and uses in behavioral sciences. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; Boston: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Briggs-Phillips M, Hobfoll SE. Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(6):825–836. doi: 10.1002/jts.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6(5):442–451. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, McEwen BS. Impact of social environment characteristics on neuroendocrine regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58(5):459–471. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS. Price of adaptation: Allostatic load and its health consequences: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(19):2259–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton-Mifflin; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(21):2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry DM, Widom CS. Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(6):415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(5):517–530. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Mechanisms linking early life stress to adult health outcomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(19):8507–8512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003890107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lehman BJ, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. Relationship of early life stress and psychological functioning to adult C-reactive protein in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60:819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sage RM, Lehman BJ, Seeman TE. Early environment, emotions, responses to stress, and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1365–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Way BM, Seeman TE. Early adversity and adult health outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:939–954. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families . Child Maltreatment 2012. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vie TL, Hufthammer KO, Holmen TL, Meland E, Breidablik HJ. Is self-rated health a stable and predictive factor for allostatic load in early adulthood? Findings from the Nord Trøndelag health study (HUNT) Social Science & Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.019. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber LJ, Cummings AL. Research and theory: Relationships among spirituality, social support and childhood maltreatment in university students. Counseling and Values. 2003;47(2):82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wegman HL, Stetler C. A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:805–812. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Toward the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989a;59:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989b;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C, Czaja S, Bentley T, Johnson MS. A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(6):1135–1144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology. 2008;27(2):149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. Sexually transmitted diseases among adults who had been abused and neglected as children: A 30-year prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(S1):S197–S203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Substance use, risky behaviors, and victimization among a US national adolescent sample. Addiction. 1994;89(2):175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang ME, Weiner N. University of Pennsylvania Greater Philadelphia Area Study. 1989. Unpublished manuscript.