Abstract

Human and animal studies have converged to suggest that caffeine consumption prevents memory deficits in aging and Alzheimer’s disease through the antagonism of adenosine A2A receptors (A2AR). To test if A2AR activation in hippocampus is actually sufficient to impair memory function and to begin elucidating the intracellular pathways operated by A2AR, we have developed a chimeric rhodopsin-A2AR protein (optoA2AR), which retains the extracellular and transmembrane domains of rhodopsin (conferring light responsiveness and eliminating adenosine binding pockets) fused to the intracellular loop of A2AR to confer specific A2AR signaling. The specificity of the optoA2AR signaling was confirmed by light-induced selective enhancement of cAMP and phospho-MAPK (but not cGMP) levels in HEK293 cells, which was abolished by a point mutation at the C-terminal of A2AR. Supporting its physiological relevance, optoA2AR activation and the A2AR agonist CGS21680 produced similar activation of cAMP and phospho-MAPK signaling in HEK293 cells, of pMAPK in nucleus accumbens, of c-Fos/pCREB in hippocampus and similarly enhanced long-term potentiation in hippocampus. Remarkably, optoA2AR activation triggered a preferential phospho-CREB signaling in hippocampus and impaired spatial memory performance while optoA2AR activation in the nucleus accumbens triggered MAPK signaling and modulated locomotor activity. This shows that the recruitment of intracellular A2AR signaling in hippocampus is sufficient to trigger memory dysfunction. Furthermore, the demonstration that the biased A2AR signaling and functions depend on intracellular A2AR loops, prompts the possibility of targeting the intracellular A2AR interacting partners to selectively control different neuropsychiatric behaviors.

Keywords: adenosine A2A receptor, hippocampus, memory, optogenetics, CREB, biased signalling, MAPK, intracellular domain of A2A receptor, striatum

Introduction

Recently six longitudinal prospective studies have established an inverse relationship between caffeine consumption and the risk of developing cognitive impairments in aging and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1-7. This is in notable agreement with animal studies, which showed that caffeine prevents memory impairments in models of AD8-10 and sporadic dementia11 and in other conditions affecting memory performance12, 13; this seems to involve the antagonism of G-protein coupled adenosine A2A receptors (A2AR), since their selective pharmacological or genetic blockade mimic caffeine’s effects8, 12, 14, 15. The convergence of human epidemiological and animal evidence led us to propose that A2AR represent a novel therapeutic target to improve cognitive impairments in neurodegenerative disorders. The validity of this target is supported by our finding that A2AR inactivation not only enhances working memory16, 17, reversal learning17, goal-directed behavior18 and Pavlovian fear conditioning19 in normal animals, but also reverse memory impairments in animal models of Parkinson’s disease20, aging15 and AD8, 9, 14. Notably, pathological brain conditions associated with memory impairment (such as AD, stress or inflammation) are associated with increased extracellular levels of adenosine21 and an up-regulation and aberrant signaling of A2AR22, 23. This prompts the hypothesis that the “abnormal” activation of A2AR in particular brain region (such as the hippocampus) is sufficient to trigger memory impairment. This critical question has yet to be answered because of the inability to control forebrain A2AR signaling in freely behaving animals with a temporal resolution relevant to behavior.

Another major unsolved question is the mechanisms operated by brain A2AR to control memory function. In fact, A2AR signaling is different in different cellular elements with distinct functions under various physiological versus pathological conditions22, 24, 25. For example, striatal and extra-striatal A2AR exert opposite control of DARPP-32 phosphorylation26, c-Fos expression26, psychomotor activity26, 27 and cognitive function19. Receptor-receptor heterodimerization has been postulated to contribute to the complexity of A2AR signaling28. Additionally, recent biochemical studies identified six G-protein interacting partners (GIP) linked to the intracellular C-terminal tail of A2AR29, 30, which raises the intriguing possibility that the interaction of A2AR intracellular domains with different GIPs may dictate the biased A2AR signaling in different cells. However, the inability to control intracellular GPCR signaling in vivo in a precise spatiotemporal manner, has prevented translation of in vitro profiles of A2AR signaling into behavior in intact animals.

To determine if the abnormal activation of A2AR signaling in hippocampus is sufficient to impair memory function in freely behaving animals and to begin elucidating the nature of the biased A2AR signaling in different brain regions, we have developed a chimeric rhodopsin-A2AR protein (optoA2AR): this merges the extracellular and transmembrane domains of rhodopsin conferring light responsiveness and the intracellular domains of A2AR conferring specific A2AR signaling, to investigate the biased A2AR signaling in defined cell populations of freely behaving animals in a temporally precise and reversible manner31. Furthermore, the selective retention of only the intracellular domains of A2AR in optoA2AR chimaera permits a critical evaluation of its particular role controlling the biased A2AR signaling. After validating the specificity and physiological relevance of light-induced optoA2AR recruitment of A2AR signaling in HEK293 cells, mouse brain slices and in freely behaving animals, we exploited its unique temporal and spatial resolution to provide direct evidence that the activation of intracellular A2AR signaling selectively in the hippocampus is sufficient to recruit cAMP and phosphorylated CREB, and alter synaptic plasticity and memory performance. Our findings also provide a direct demonstration that the intracellular control of the biased A2AR signaling in striatal and hippocampal neurons triggers distinct signaling and behavioral responses.

Materials and Methods

The detailed methods are described in the “Supplemental”.

Design and construction of the optoA2AR vector

We constructed a fusion gene encoding a chimaera (optoA2AR) where the intracellular loops 1, 2 and 3 and the C-terminal of rhodopsin were replaced with those of A2AR and the C-terminal sequence of bovine rhodopsin (TETSQVAPA) was added to the C-terminal of optoA2AR. Lastly, codon optimized sequences of optoA2AR were fused to the N-terminus of mCherry (with its start codon deleted) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Characterization of optoA2AR signaling in HEK293 cells.

Design (a) of optoA2AR and its expression (b,c) in HEK293 cells 24-hr after transfection. (b): Western blot analysis of optoA2AR with a molecular weight of 75-100 kD. (c): co-localization of A2AR-immunostaining (green) with mCherry-expressing (red) in optoA2AR–positive cells. (d,e) Light induction of p-MAPK in optoA2AR-expressing cells. d: p-MAPK-immunostaining of optoA2AR-expressing cells before and after light stimulation. e: Western blot analysis of p-MAPK and MAPK expression in response to light. (f,h). Light-induced increase of cAMP (f; plasmid: F(1,62)=126.7, p<0.001; light stimulation, F(1,62)=67.8, p<0.001; plasmid × light, F(1,62)=89.4, p<0.001, two way ANOVA) but not of cGMP (g; light, F(1,62)=0.110, p>0.05, two way ANOVA) or IP1 production (h; light, F(1,62)=0.110, p>0.05, two way ANOVA) in HEK293 cells transfected with optoA2AR. ***=p<0.001, comparing optoA2AR with control; ###=p<0.001 compared to the dark, n=16, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc t-test. (i) Time course of opto-A2AR-induced cAMP accumulation after light stimulation. One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc t-test. (j) Effect of the mutations Ser400Ala and Thr324Ala of the C-terminal of optoA2AR on light optoA2AR-induced cAMP accumulation. **=p<0.01, Student’s t test. Each experiment was done in duplicates or triplicates and repeated at least three times. Scale bar = 50μm

Transfection and assessment of optoA2AR signaling in HEK cells

48-hr after transfection, all-trans-retinal (25μM) was added to HEK293 cells that were then illuminated (500nm, 3mW/mm2) for 60-sec. The cells were lysed 30-min after light illumination to analyze cAMP using cAMP-Glo™ assay (Promega), cGMP by HTRF-cGMP assay and IP1 by HTRF-IP1 assay kit (CisBio). For Western blot, cells were homogenized 10 min after light illumination using a PARIS Kit (Invitrogen).

Activation of optoA2AR signaling in the brain

Recombinant AAV vectors were constructed with a CaMKIIα promoter by cloning the optoA2AR-mCherry into pAAV-CaMKIIα-eNpHR 3.0-EYFP (Addgene). Viral particles were packaged and purified as serotype 5-positive at the University of North Carolina with titers of 1.5-2.0×1012 particles/mL. We injected 1.0μL of AAV5-CaMKIIα-optoA2AR-mCherry virus or 0.75μL of AAV5-CaMKIIa-mCherry (“control”) virus into the right nucleus accumbens or hippocampus. After 2 weeks, 473nm DPSS laser light was delivered via a patch cable with 50ms pulse width and ~3-5mW/mm2 power density.

Behavioral tests

The Y-maze test for spatial recognition memory task was based on exploration of novelty, as previously described12,32. During the second trial (retrieval phase), the mice had access to the 3 arms for 5-min with light “ON”. The time spent in each arm and total locomotor activity was measured by a video-tracking system.

Immunohistochemistry

The targeted expression of optoA2AR and of its molecular signaling (c-Fos, pCREB, pMAPK) in NAc and hippocampus were determined by immunohistochemistry as described previously17, 19,26. Mice were killed 10 min after optical stimulation or 15-min after injecting 2.0μL of the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 (0.5μg/μL) in NAc or hippocampus to activate endogenous A2AR. We analyzed 3 fields/section, 3 sections/mouse, 3 mice/group.

Electrophysiological recordings in hippocampal slices

The recording of the evoked field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP) in the CA1 stratum radiatum upon stimulation of Schaffer fibers every 20-sec, were as previously described69 in hippocampal slices (400μm) prepared two weeks after transfection with AAV5-CaMKIIa-mCherry without or with optoA2AR in hippocampus. A high frequency stimulation (HFS) train (100Hz, 1-sec) was used to induce long-term potentiation (LTP). Light stimuli, applied immediately before HFS, consisted of 3000 light pulses (465nm, 50ms pulse width, ~3-5mW/mm2 power density) over 300-sec and the optic fiber was placed over the slice between the stimulation and recording electrodes. CGS21680 (30nM; Tocris) was added to the superfusion solution 20-min before HFS onwards.

Western blot and immunocytochemistry of total membranes and synaptosomes

Total membranes and synaptosomes from the hippocampus were prepared using sucrose/Percoll differential centrifugations and Western blot analysis was carried out as previously described70 using an antibody against the third intracellular loop of A2AR (1:500; Millipore). The immunocytochemical analysis to detect the presence of optoA2AR in glutamatergic terminals, was done as previously71, by detecting the co-localization of mCherry fluorescence with vGluT1 immunoreactivity (1:2500, Synaptic Systems).

Results

Light activation of optoA2AR specifically recruits A2AR signaling in HEK293 cells

We engineered a light activated chimeric protein able to recruit A2AR signaling, optoA2AR, by replacing the intracellular domains of rhodopsin with those of A2AR (Figure 1a). 24-h after transfecting human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells with optoA2AR, we observed a single band with a 80 kD molecular weight, expected for optoA2AR (Figure 1b), using an A2AR antibody targeting the third intracellular loop of A2AR. We also detected the red fluorescence of mCherry, included in the optoA2AR construct, largely restricted to the cell surface (Figure 1c), similar to that obtained using the A2AR antibody.

A2AR activate the GS/Golf-cAMP pathway as well as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway in a GS-independent manner25. Light stimulation of HEK293-optoA2AR cells (for 60-sec) increased MAPK phosphorylation (p-MAPK), in contrast with the weak p-MAPK immunoreactivity in light stimulated cells transfected with the pcDNA3.1 vector (Figure 1d), which was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 1e). Light stimulation of HEK293-optoA2AR cells also increased cAMP levels by 2-fold (immunoassay after 20-min), compared to non-stimulated HEK293-optoA2AR cells and to light-stimulated cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 (Figure 1f; p<0.001, two way ANOVA). Thus, optoA2AR specifically recruits the two parallel A2AR signaling pathways, namely GS-cAMP and MAPK signaling in HEK293 cells.

Supporting the specificity of optoA2AR signaling, light stimulation of HEK293-optoA2AR cells induced cAMP and p-MAPK signaling (Figure 1e, 1f) but did not affect either cGMP (the rhodopsin transducing system, Figure 1g) or IP1 production (a degradation product of IP3, associated with Gq signaling, Figure 1h). Of note, light stimulation of optoA2AR rapidly increased cAMP and pMAPK levels in HEK293 cells within 1-min, peaking at 15-30-min and declining to basal level at 60-90-min (Figure 1i; p<0.05, One way ANOVA). Further reinforcing the selectivity of optoA2AR to trigger cAMP accumulation, a Ser400Ala point mutation in an A2AR phosphorylation site critical for A2AR-D2R receptor interaction33, but not a Thr324Ala point mutation in an A2AR phosphorylation site critical for short-term desensitization30, of the C-terminals of optoA2AR abolished the light optoA2AR-induced cAMP accumulation (Figure 1j; **p<0.01, Student’s t test). Thus, optoA2AR signaling is specific and attributed to the unique amino acid composition of its C-terminus.

Light optoA2AR activation triggers an A2AR signaling identical to the pharmacological activation of endogenous A2AR both in HEK293 cells and mouse brain

To demonstrate the physiological relevance of optoA2AR signaling, we first compared in HEK293 cells cAMP levels and p-MAPK induced by either light activation of optoA2AR or CGS21680 (A2AR agonist) activation of wild-type A2AR. Light optoA2AR activation increased cAMP (Figure 2b; p<0.001two-way ANOVA) to levels similar to these triggered by CGS21680 (200 nM) in cells transfected with A2AR-mCherry (Figure 2a; p<0.001,two-way ANOVA). Moreover, in cells co-transfected with A2AR-mCherry and optoA2AR, co-stimulation with light and CGS21680 produced additive effects on both cAMP level (Figure 2c; light, F(1,43)=7.243, p<0.01; CGS21680, F(3,43)=32.674, p<0.001; light × CGS21680 interaction, F(3,43)=0.336, p>0.05, two-way ANOVA) and p-MAPK. Thus, optoA2AR and CGS21680 produced similar A2AR signaling with additive effects in HEK293 cells.

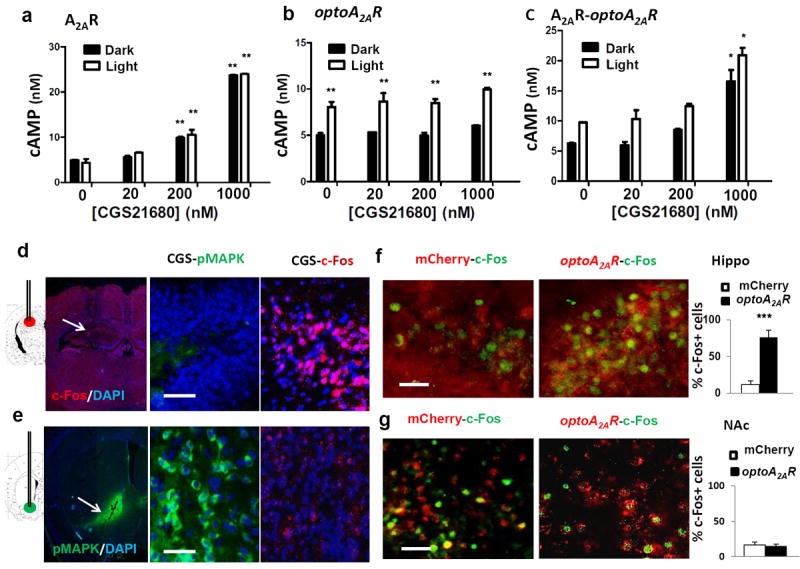

Figure 2. OptoA2AR and CGS21680 produced additive induction of cAMP in HEK293 cells and indistinguishable biased A2AR signaling in NAc and hippocampus.

(a,b,c): HEK293 cells were transfected with wild-type A2AR (a) or optoA2AR (b) or co-transfected with wild-type A2AR and optoA2AR (c). (a) 24-hrs after transfection, cells transfected with wild-type A2AR were treated with the A2AR agonist CGS21680 (20, 100, 200 and 1000nM) and displayed a concentration-dependent increase of cAMP levels. Light activation of optoA2AR-transfected HEK293 cells increased cAMP levels (b; for light, F(1,31)=60.721, p<0.001; for CGS21680, F(3,31)=2.163, p>0.05; light × CGS21680 interaction, F(3,31)=0.155, p>0.05, two-way ANOVA) similar to that induced by 200nM CGS21680 (a; for light, F(1,46)=0, p>0.05; for CGS21680, F(3,46)=312.799, p<0.001; light × CGS21680 interaction, F(3,46)=0.547, p>0.05, two-way ANOVA). Co-stimulation of light and CGS21680 in cells co-transfected with optoA2AR and wild-type A2AR produced an additive effect on cAMP levels (c; for light stimulation, F(1,43)=7.243, p<0.01; for CGS21680, F(3,43)=32.674, p<0.001; light × CGS21680 interaction, F(3,45)=0.336, p>0.05, two-way ANOVA). *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc t-test. Following intra-accumbal injection, CGS21680 markedly induced p-MAPK expression (green) but not c-Fos expression around the injection site (d, lower panel). Following intra-hippocampal injection, CGS21680 induced c-Fos expression (right) but not p-MAPK expression (left) around the injection site (e, upper panel). (f): Two weeks after intra-hippocampal injection of AAV5-optoA2AR, light stimulation for 5-min induced c-Fos expression in optoA2AR-positive cells but not in cells transfected with AAV5-mCherry. By contrast, light stimulation of optoA2AR in NAc did not affect c-Fos expression (g). Bar graphs (f, g) are c-Fos cell counts (averaged from 3 fields of each section, 3 section per mouse, 3 mice per group). ***=p<0.001, Student’s t test comparing the optoA2AR with the mCherry. Scale bar=50 μm (d-g).

We further compared A2AR signaling (c-Fos and p-MAPK) in hippocampus and nucleus accumbens (NAc) induced by endogenous A2AR activation in wild-type mice and by optoA2AR in transfected A2AR knockout mice. Intra-hippocampal injection of CGS21680 (0.93nmol/μL) significantly increased c-Fos expression within 15-min specifically in the cells surrounding the injection site (Figure 2d). By contrast, intra-accumbal injection of CGS21680 markedly induced p-MAPK (Figure 2e). Thus, endogenous A2AR activation elicits a brain region-specific A2AR signaling in the forebrain (c-Fos in hippocampus and p-MAPK in NAc). Accordingly, light optoA2AR stimulation in hippocampus significantly increased c-Fos expression specifically in the optoA2AR-expressing cells underneath the cannula (Figure 2f) whereas optoA2AR activation in NAc markedly induced p-MAPK (Figure 5d, 5e) but not c-Fos (Figure 2g). This demonstrates a similarly biased A2AR signaling triggered by optoA2AR and CGS21680, i.e. c-Fos in hippocampus and p-MAPK in NAc, supporting the ability of optoA2AR to mimic the endogenous A2AR signaling in the brain.

Figure 5. Light activation of accumbal optoA2AR triggered p-MAPK phosphorylation and locomotor response.

(a) Top left: Schematic illustration and mCherry (optoA2AR) under CaMKIIa promoter in NAc after focal injection of AAV5-optoA2AR-mCherry int NAc (AP, +1.1 mm; ML, ±1.4mm; DV, +4.5 mm). Top left: Schematic illustration and location of mCherry in the core and shell of NAc. Top right: A2AR-immunostaining (green) localized in mCherry-expressing (red) optoA2AR–positive cells. Bottom left: optoA2AR-mCherry were co-localized in NeuN-positive (green) but not GFAP-positive cells. (b) Expression of optoA2AR in enkephalin (ENK)-positive and substance-P (SP)-positive medium-sized spiny neurons. (c,d) Light induction of p-CREB (c) and p-MAPK (d) (green) in NAc at two weeks after intra-NAc injection of AAV5-optoA2AR (right) or AAV5-mCherry (left). Light stimulation produced scattered expression of p-CREB but triggered a robust induction of p-MAPK with mCherry-expressing in optoA2AR–positive cells (right panels). (e) Quantitative analysis of light induction of phospho-CREB and phospho-MAPK in optoA2AR-positive cells but not in cells transfected with AAV5-mCherry. pCREB/pMAPK-positive cell accounts were obtained from 3 fields per section, 3 sections per mouse, 3 mice per group. ***=p<0.001, Student’s t test comparing the optoA2AR with the mCherry. (f, g) Light stimulation of optoA2AR in NAc increased the total distance travelled at the acquisition phase (g; for AAV vector, F(1, 44)=10.11,p<0.003; for behavioral phase, F(1,44)=25.08, p<0.001; AAV vector × behavioral phase, F(1,44)=18.68, p <0.001, two-way ANOVA; ***p<0.001, ###p<0.001, Bonferroni post-hoc test, comparing optoA2AR with mCherry) but had no effect time spent in the novel arm during the 5-min “Light-On” period, compared with that of the mCherry (f; p = 0.276, Student’s t test). Scale bar = 50 μm. Green arrow: co-localization of optoA2AR with phospho-CREB; red arrow: phospho-CREB expression only; white arrow: co-localization of optoA2AR with ENK, SP, phospho-CREB or phospho-MAPK; green arrow: ENK, SP, phospho-CREB or phospho-MAPK only; red arrow: mCherry expression only.

Targeted expression and light activation of optoA2AR in glutamatergic terminals of the hippocampus controlling LTP in hippocampal slices

The A2AR antibody detected a single 45kD band (endogenous A2AR) in striatal membranes, whereas A2AR levels were barely detectable in hippocampal samples, compatible with the 20-times lower density of A2AR in hippocampus versus striatum70. Importantly, this A2AR antibody designed against the third intracellular loop of A2AR recognized two bands of 80kD and 95kD selectively in hippocampus transfected with AAV-mCherry-optoA2AR, but not with AAV-mCherry (Figure 3a), with a density in synaptosomes similar to that detected in total membranes (n=3, p>0.05, Student’s t test). Furthermore, the immunocytochemistry analysis of purified synaptosomes (Figure 3b) allowed identifying mCherry fluorescence in glutamatergic nerve terminals (i.e. immunopositive for vesicular glutamate transporters type-1, vGluT1) only from hippocampus transfected with AAV-mCherry-optoA2AR (n=3), but not with AAV-mCherry (not shown). This indicates that optoA2AR is present in hippocampal glutamatergic nerve terminals, where endogenous A2AR have been identified71.

Figure 3. Targeted expression and light activation of optoA2AR in glutamatergic terminals of hippocampus induced hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) in brain slices.

(a) Representative Western blot analysis showing that an antibody against the third intracellular loop of A2AR recognized two bands at 80 and 95 kDa in hippocampal synaptosomes as well as in total membranes from mice transfected with AAV-mCherry-optoA2AR (optoA2AR) but not from mice transfected with AAV-mCherry, compatible with the localization of optoA2AR in hippocampal synapses (n=3). (b) Representative single nerve terminal immunocytochemistry identifying that vesicular glutamate transporter type 1 (vGluT1, a marker of glutamatergic terminals; green) and mCherry immunoreactivity (red) were found to be co-localized (arrows identifying yellow in ‘merged’) in hippocampal synaptosomes from mice transfected with AAV-mCherry-optoA2AR (optoA2AR), whereas this was not observed for mice transfected with AAV-mCherry (not shown) (n=3). (c) Accordingly, light stimulation (3000 pulses of 50-ms duration each during 300-sec) of slices from mice transfected with AAV-mCherry-optoA2AR, applied before a high-frequency train (100Hz for 1-sec), enhanced the amplitude of LTP compared to non-light stimulated slices, measured as an increased slope of field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSP) recorded in the stratum radiatum of the CA1 area upon stimulation of the afferent Schaffer fibers (c), whereas light stimulation failed to modify LTP amplitude in mice transfected with AAV-mCherry (not shown). This essentially mimics the effect of the pharmacological activation of endogenous A2AR with the selective A2AR agonist CGS21680 (30nM), in slices from mice transfected either with AAV-mCherry-optoA2AR (d) or with AAV-mCherry (e). Representative images (a,b) and data (mean±SEM, c-e) are from n=3 independent mice. *=p<0.05, Student’s t test.

Additionally, we observed (Figure 3c) that the amplitude of long-term potentiation (LTP) triggered by high-frequency light stimulation (HFS) was larger upon light stimulation (5-min before HFS) of hippocampal slices expressing optoA2AR (197.3±2.9% over baseline) than without light stimulation (137.7±2.0% over baseline, n=3; p>0.05, Student’s t test). By contrast, light stimulation did not modify LTP amplitude in hippocampal slices expressing only mCherry (138.9±2.7% vs. 142.5±1.5% over baseline with or without light stimulation, respectively, n=3; p>0.05, Student’s t test) (data not shown). This enhancement upon light-induced optoA2AR activation was similar to the impact of a pharmacological activation of endogenous A2AR with the A2AR agonist, CGS21680 (30nM) (Figure 3d) as well as in slices from mice transfected with AAV-mCherry (Figure 3e), as occurs in wild-type animals72. This shows that light activation of optoA2AR can mimic an established physiological response operated by endogenous A2AR in hippocampus44,69.

Optogenetic optoA2AR activation in hippocampus recruits CREB phosphorylation and impairs memory performance

Two weeks after the focal injection of AAV5-(CaMKIIα promoter-driven)-optoA2AR-mCherry (Figure 4a), light stimulation in the dorsal hippocampus significantly increased the levels of phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) (Figure 4c,4d; p<0.001, Student’s t test) specifically in the optoA2AR-expressing neurons underneath the cannula, consistent with the A2AR-GS-cAMP pathway as the major A2AR signaling pathway in hippocampus25. Similar to p-CREB recruitment, light stimulation significantly elevated c-Fos in the optoA2AR-expressing neurons in hippocampus (Figure 2f; p<0.001, Student’s t test), whereas it did not induce p-MAPK (Figure 4b,4d). Thus, in hippocampal neurons, light optoA2AR activation preferentially stimulates the cAMP-PKA pathway, leading to p-CREB and c-Fos expression, without significant effect on the p-MAPK pathway.

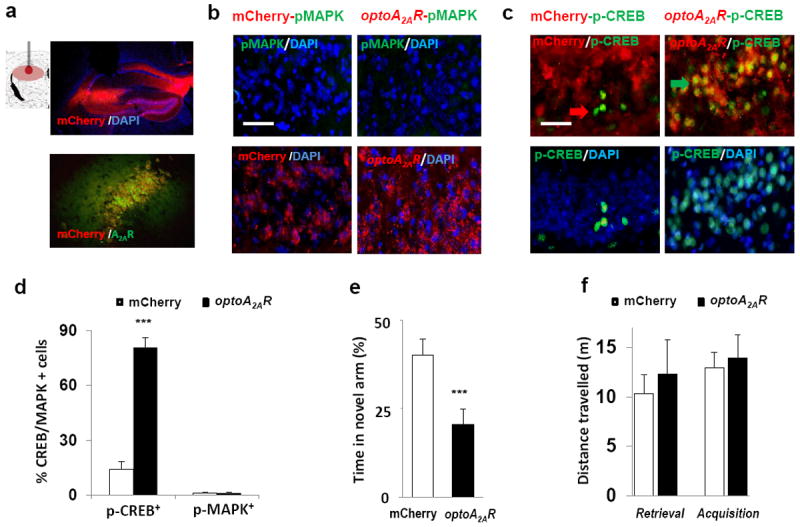

Figure 4. Light activation of hippocampal optoA2AR triggers CREB phosphorylation and memory impairment.

(a) Upper panel: Schematic illustration of transplanted cannula targeting hippocampus and expression of mCherry (optoA2AR) under CaMKIIa promoter in hippocampus after focal injection of AAV5-optoA2AR-mCherry (AP, -2.2 mm; ML, ±1.5mm; DV, +2.3 mm). Lower panel: co-localization of A2AR-immunostaining (green) with mCherry-expressing (red) in optoA2AR–expressing cells. (b,c) Light stimulation of optoA2AR in hippocampus for 5-min induced phospho-CREB (b,d) but not phospho-MAPK (c,d, p=<0.001, Student’s t test) in optoA2AR-positive cells but not in cells transfected with AAV5-mCherry (3 fields/section, 3 sections/mouse, 3 mice/group). (e) Light stimulation of optoA2AR signaling in the hippocampus during the retrieval phase impaired spatial recognition memory with decreased time in the novel arm (p=<0.001, Student’s t test) of the Y-maze but had no effect on total distance travelled (f; AAV vector, F(1,41) = 0.45, p>0.05, two-way ANOVA) during on the 5-min “Light-On” period, compared with that of the control. Green arrow: co-localization of optoA2AR with phospho-CREB; red arrow: phospho-CREB expression only. Scale bar=50μm.

To address the central question whether A2AR activation in hippocampus is sufficient to impair memory performance, we tested if triggering hippocampal optoA2AR signaling affected spatial reference memory performance using a two-visit version of the Y-maze test. Light optoA2AR activation in hippocampus during the 5-min testing period reduced about 2-fold the time spent in the novel arm compared with mice transfected with AAV-mCherry (control) only (Figure 4e; p<0.001, Student’s t test). These short-term reference memory impairments were not due to changes in locomotion as gauged by the unaltered total distance travelled in the Y-maze (Figure 4f). Thus, transient activation of optoA2AR in a set hippocampal neurons is sufficient to recruit p-CREB signaling and deteriorate memory performance.

Light optoA2AR stimulation in nucleus accumbens recruits MAPK phosphorylation and selectively modulates motor activity

We next examined the impact of light optoA2AR activation in NAc and hippocampus on the two A2AR signaling pathways (p-CREB and p-MAPK). Since GPCR can produce a biased signaling simply due to different receptor levels, we used the same CaMKIIα promoter to drive similar levels of optoA2AR expression in hippocampal and striatal neurons34, 35, to eliminate different optoA2AR expression levels as a possible cause of a biased A2AR signaling in these two forebrain regions36. OptoA2AR was selectively expressed in accumbal neurons (co-localized with Neu+ neurons, but not with GFAP+ astrocytes) in the core of NAc (Figure 5a). Using enkephalin (ENK) and substance-P (SP) immunostaining to identify the indirect and direct pathway neurons37, we found that optoA2AR was expressed in both ENK-containing (52%) and SP-containing (43%) neurons in NAc (Figure 5b). Importantly, light activation of optoA2AR in NAc for 5-min markedly increased p-MAPK (Figure 5d,5e; p<0.001, Student’s t test), with little induction of p-CREB and c-Fos (Figure 5c, 5e, 2g). Thus, the activation of A2AR signaling by optoA2AR in NAc preferentially involved the MAPK pathway rather than the cAMP-PKA mediated c-Fos/CREB pathway.

In parallel with the preferential activation of p-MAPK signaling, light optoA2AR activation in NAc for 5-min did not affect memory performance in the modified Y-maze test (Figure 5f; p=0.276, Student’s t test), but robustly increased locomotor activity (83% increase of travelled distance in the Y-maze, Figure 5g, and in the open field test) (for AAV vector × behavioral phase, F(1,45)=18.68, p<0.001, two-way ANOVA). The observed motor stimulant effect resulting from optoA2AR activation in NAc, instead of a motor depression observed upon accumbal administration of CGS2168038, 39, was expected in view of the expression of optoA2AR in both striatopallidal and striatonigral neurons using the CaMKIIα promoter35, 36 (rather than the selective expression of endogenous A2AR in striatopallidal neurons prompted by the A2AR promoter40). This pitfall was however essential to circumvent the confounding effect of a 20-fold differential expression of A2AR in these two brain regions as a possible cause for the biased A2AR signaling. Overall, the present findings show that A2AR trigger a biased A2AR signaling in different forebrain regions (cAMP in hippocampus and p-MAPK in NAc) in parallel with an impact on distinct behaviors (memory in hippocampus and locomotion in NAc).

Discussion

The development and validation of the optoA2AR approach to mimic endogenous A2AR signaling allowed the novel conclusion that the recruitment of A2AR signaling in the dorsal hippocampus is sufficient to trigger a selective memory deficit. This is in accordance with the imbalance of the local extracellular adenosine levels21 and up-regulation of A2AR in animal models of aging41, sporadic dementia11, AD10, as well as in the human AD brain42, namely in hippocampal nerve terminals12, 13, a situation that was mimicked by hippocampal optoA2AR expression under control of the CaMkIIα promoter. Indeed, optoA2AR was detected in hippocampal synaptosomes, namely in glutamatergic synapses where endogenous A2AR are identified71 and upregulated upon aging and neurodegeneration. This provides an anatomical basis for optoA2AR control of p-CREB signaling, synaptic activity and memory performance. Indeed, the light activation of optoA2AR in hippocampal slices mimicked a well-established physiological response operated by endogenous A2AR, the control of hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP)44,69. Furthermore, optoA2AR activation in hippocampus triggers CREB phosphorylation and impairs memory performance. These findings are consistent with the canonical cAMP/PKA pathway activated by hippocampal A2AR25 and with the established role of CREB phosphorylation controlling synaptic plasticity and long-term memory43 through neuronal excitability and transcription, and with specific deficits of memory retrieval observed in mice expressing a time-controlled active CREB variant44. This ability of hippocampal optoA2AR activation in glutamate synapses to control memory dysfunction and its purported neurophysiological correlate LTP, decisively strengthens the relation between A2AR and memory performance that had so far largely relied on the demonstration that A2AR blockade alleviated memory dysfunction8, 9, 12, 14, 15. Furthermore, this ability to place A2AR functioning as a sufficient factor to imbalance memory bolsters the rationale to probe the therapeutic effectiveness of A2AR antagonists to manage memory impairment22, 23. This notion is further warranted by the striking convergence of epidemiological1-7 and animal8-20 evidence supporting the therapeutic benefit of caffeine and A2AR antagonists to improve cognition. This aim should be facilitated by the safety profile of A2AR antagonists, tested in over 3000 parkinsonian patients22.

The design of optoA2AR also allowed identifying a critical role solely attributable to the intracellular domains of A2AR to dictate the biased A2AR signaling and function in neurons of different brain regions. Contrary to the widely accepted view that ligand-receptor interactions are the molecular basis directing the biased GPCR signaling, the distinct molecular and behavioral responses obtained upon optoA2AR activation in different brain regions show that they are only dependent on an intracellular mechanism probably related with the differential association with different GIPs in different cell types. In fact, the cell-specific expression of intracellular GIPs provides a rich molecular resource45 whereby A2AR signaling in the brain is specifically wired according to the needs of each cell type. In particular, the long and flexible A2AR C-terminus29 contains several consensus sites (e.g. YXXGφ)30 required for MAPK activation46, interaction with BDNF receptors (TrkB)47, with FGF48, with p5349, 50, with a large set of downstream signaling effectors such as G proteins, GPCR kinases, arrestins and with at least six GIPs (actinin, calmodulin, Necab2, translin associated protein X, ARNO/cytohesin-2, ubiquitin-specific protease-4)29. Thus, targeting A2AR intracellular domains offers an additional layer of selectivity to manipulate A2AR signaling that is not attainable only by the ligand-receptor interaction. Thus, selectively targeting A2AR intracellular domains and their interacting GIPs in specific brain regions emerges as a novel strategy to obtain therapeutic effects with minimal side effects, as achieved with trans-membrane peptides to specifically disrupt the intracellular interaction between NMDA receptors and PSD9551, 52 and between 5-HT2c-PENT53. If the critical interaction between intracellular domains of A2AR and GIPs are general features of GPCRs, the “optoGPCR” approach targeting intracellular domains of GPCRs may represent a novel drug discovery strategy for the largest protein superfamily in the human genome.

The significance of these novel insights is decisively strengthened by the demonstrated specificity and rapid induction of the optoA2AR signaling. The specificity of optoA2AR signaling is supported by the selective optogenetic induction of cAMP and MAPK signaling without affecting cGMP (rhodopsin) and IP3 (Gq) signaling and by the mutational analysis demonstrating that optoA2AR signaling is specifically attributed to the unique amino acid composition of the A2AR C-terminus. Moreover, the comparable activation of A2AR signaling in HEK293 cells and the indistinguishable pattern of the biased A2AR signaling in NAc and hippocampus as well as the similar enhancement of hippocampal LTP triggered by optoA2AR and CGS21680 supports that optoA2AR signaling largely captures the physiological function of the native A2AR. Different from opsin-based optogenetics, opto-A2AR signals through GPCR signaling allows a control of intracellular A2AR signaling by light, which we now report to involve a rapid induction, consistent with similar rapid physiological response (Ton1/2= ~1-sec) of other GPCR light activated chimaera58-61. Thus, the temporal and spatial control of specific A2AR signaling afforded by optoA2AR in freely behaving animals paves the way to probe the role of A2AR in defined forebrain circuits responsible for behaviors ranging from motor control, fear, addiction, mood or decision making54, 55.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NS041083-11, NS073947, the MacDonald Foundation for Huntington’s Research, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (grant W911NF-10-1-0059) and Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD Independent Investigator Grant). We warmly thank João Peça (CNC) for providing the calibrated light source for the slice experiments.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Authors declare no conflict of interest for the work presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.van Boxtel MP, Schmitt JA, Bosma H, Jolles J. The effects of habitual caffeine use on cognitive change: a longitudinal perspective. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75(4):921–927. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hameleers PA, Van Boxtel MP, Hogervorst E, Riedel WJ, Houx PJ, Buntinx F, et al. Habitual caffeine consumption and its relation to memory, attention, planning capacity and psychomotor performance across multiple age groups. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2000;15(8):573–581. doi: 10.1002/hup.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, Hebert R, Helliwell B, Hill GB, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):445–453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Gelder BM, Buijsse B, Tijhuis M, Kalmijn S, Giampaoli S, Nissinen A, et al. Coffee consumption is inversely associated with cognitive decline in elderly European men: the FINE Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(2):226–232. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie K, Carriere I, de Mendonca A, Portet F, Dartigues JF, Rouaud O, et al. The neuroprotective effects of caffeine: a prospective population study (the Three City Study) Neurology. 2007;69(6):536–545. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266670.35219.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelber RP, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Ross GW, White LR. Coffee intake in midlife and risk of dementia and its neuropathologic correlates. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(4):607–615. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eskelinen MH, Ngandu T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: a population-based CAIDE study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(1):85–91. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dall’Igna OP, Fett P, Gomes MW, Souza DO, Cunha RA, Lara DR. Caffeine and adenosine A2a receptor antagonists prevent beta-amyloid (25-35)-induced cognitive deficits in mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;203(1):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunha GM, Canas PM, Melo CS, Hockemeyer J, Muller CE, Oliveira CR, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor blockade prevents memory dysfunction caused by beta-amyloid peptides but not by scopolamine or MK-801. Exp Neurol. 2008;210(2):776–781. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arendash GW, Schleif W, Rezai-Zadeh K, Jackson EK, Zacharia LC, Cracchiolo JR, et al. Caffeine protects Alzheimer’s mice against cognitive impairment and reduces brain beta-amyloid production. Neuroscience. 2006;142(4):941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinosa J, Rocha A, Nunes F, Costa MS, Schein V, Kazlauckas V, et al. Caffeine consumption prevents memory impairment, neuronal damage, and adenosine A2A receptors upregulation in the hippocampus of a rat model of sporadic dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(2):509–518. doi: 10.3233/JAD-111982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cognato GP, Agostinho PM, Hockemeyer J, Muller CE, Souza DO, Cunha RA. Caffeine and an adenosine A2A receptor antagonist prevent memory impairment and synaptotoxicity in adult rats triggered by a convulsive episode in early life. J Neurochem. 2010;112(2):453–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duarte JM, Agostinho PM, Carvalho RA, Cunha RA. Caffeine consumption prevents diabetes-induced memory impairment and synaptotoxicity in the hippocampus of NONcZNO10/LTJ mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e21899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canas PM, Porciuncula LO, Cunha GM, Silva CG, Machado NJ, Oliveira JM, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor blockade prevents synaptotoxicity and memory dysfunction caused by beta-amyloid peptides via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29(47):14741–14751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prediger RD, Batista LC, Takahashi RN. Caffeine reverses age-related deficits in olfactory discrimination and social recognition memory in rats. Involvement of adenosine A1 and A2A receptors. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(6):957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou SJ, Zhu ME, Shu D, Du XP, Song XH, Wang XT, et al. Preferential enhancement of working memory in mice lacking adenosine A2A receptors. Brain Res. 2009;1303:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei CJ, Singer P, Coelho J, Boison D, Feldon J, Yee BK, et al. Selective inactivation of adenosine A2A receptors in striatal neurons enhances working memory and reversal learning. Learn Mem. 2011;18(7):459–474. doi: 10.1101/lm.2136011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu C, Gupta J, Chen JF, Yin HH. Genetic deletion of A2A adenosine receptors in the striatum selectively impairs habit formation. J Neurosci. 2009;29(48):15100–15103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4215-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei CJ, A E, Gomes CA, Singer P, Wang Y, Boison D, Cunha RA, Yee BK, Chen JF. Regulation of Fear Responses by Striatal and Extrastriatal Adenosine A2A Receptors in Forebrain. Biol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadowaki Horita T, Kobayashi M, Mori A, Jenner P, Kanda T. Effects of the adenosine A2A antagonist istradefylline on cognitive performance in rats with a 6-OHDA lesion in prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;230(3):345–352. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunha RA, Almeida T, Ribeiro JA. Parallel modification of adenosine extracellular metabolism and modulatory action in the hippocampus of aged rats. J Neurochem. 2001;76(2):372–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JF, Eltzschig HK, Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors as drug targets--what are the challenges? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(4):265–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunha RA, Agostinho PM. Chronic caffeine consumption prevents memory disturbance in different animal models of memory decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S95–116. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JF, Sonsalla PK, Pedata F, Melani A, Domenici MR, Popoli P, et al. Adenosine A2A receptors and brain injury: broad spectrum of neuroprotection, multifaceted actions and “fine tuning” modulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83(5):310–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fredholm BB, Chern Y, Franco R, Sitkovsky M. Aspects of the general biology of adenosine A2A signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83(5):263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen HY, Canas PM, Garcia-Sanz P, Lan JQ, Boison D, Moratalla R, et al. Adenosine A2A Receptors in Striatal Glutamatergic Terminals and GABAergic Neurons Oppositely Modulate Psychostimulant Action and DARPP-32 Phosphorylation. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen HY, Coelho JE, Ohtsuka N, Canas PM, Day YJ, Huang QY, et al. A critical role of the adenosine A2A receptor in extrastriatal neurons in modulating psychomotor activity as revealed by opposite phenotypes of striatum and forebrain A2A receptor knock-outs. J Neurosci. 2008;28(12):2970–2975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciruela F, Casado V, Rodrigues RJ, Lujan R, Burgueno J, Canals M, et al. Presynaptic control of striatal glutamatergic neurotransmission by adenosine A1-A2A receptor heteromers. J Neurosci. 2006;26(7):2080–2087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3574-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keuerleber S, Gsandtner I, Freissmuth M. From cradle to twilight: the carboxyl terminus directs the fate of the A2A-adenosine receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(5):1350–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mundell S, Kelly E. Adenosine receptor desensitization and trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(5):1319–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(9):1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dellu F, Fauchey V, Le Moal M, Simon H. Extension of a new two-trial memory task in the rat: influence of environmental context on recognition processes. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1997;67(2):112–120. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borroto-Escuela DO, Romero-Fernandez W, Tarakanov AO, Gomez-Soler M, Corrales F, Marcellino D, et al. Characterization of the A2AR-D2R interface: focus on the role of the C-terminal tail and the transmembrane helices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402(4):801–807. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Britt JP, Benaliouad F, McDevitt RA, Stuber GD, Wise RA, Bonci A. Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron. 2012;76(4):790–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chuhma N, Tanaka KF, Hen R, Rayport S. Functional connectome of the striatal medium spiny neuron. J Neurosci. 2011;31(4):1183–1192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3833-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenakin T, Christopoulos A. Signalling bias in new drug discovery: detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):205–216. doi: 10.1038/nrd3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Susel Z, Chase TN, Monsma FJ, Jr, et al. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science. 1990;250(4986):1429–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.2147780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hauber W, Munkle M. Motor depressant effects mediated by dopamine D2 and adenosine A2A receptors in the nucleus accumbens and the caudate-putamen. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;323(2-3):127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barraco RA, Martens KA, Parizon M, Normile HJ. Role of adenosine A2a receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1994;18(3):545–553. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svenningsson P, Le Moine C, Fisone G, Fredholm BB. Distribution, biochemistry and function of striatal adenosine A2A receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59(4):355–396. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canas PM, Duarte JM, Rodrigues RJ, Kofalvi A, Cunha RA. Modification upon aging of the density of presynaptic modulation systems in the hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(11):1877–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albasanz JL, Perez S, Barrachina M, Ferrer I, Martín M. Up-regulation of adenosine receptors in the frontal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2008;18(2):211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benito E, Barco A. CREB’s control of intrinsic and synaptic plasticity: implications for CREB-dependent memory models. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33(5):230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viosca J, Malleret G, Bourtchouladze R, Benito E, Vronskava S, Kandel ER, et al. Chronic enhancement of CREB activity in the hippocampus interferes with the retrieval of spatial information. Learn Mem. 2009;16(3):198–209. doi: 10.1101/lm.1220309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bockaert J, Perroy J, Bécamel C, Marin P, Fagni L. GPCR interacting proteins (GIPs) in the nervous system: Roles in physiology and pathologies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:89–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gsandtner I, Charalambous C, Stefan E, Ogris E, Freissmuth M, Zezula J. Heterotrimeric G protein-independent signaling of a G protein-coupled receptor. Direct binding of ARNO/cytohesin-2 to the carboxyl terminus of the A2A adenosine receptor is necessary for sustained activation of the ERK/MAP kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(36):31898–31905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajagopal R, Chen ZY, Lee FS, Chao MV. Transactivation of Trk neurotrophin receptors by G-protein-coupled receptor ligands occurs on intracellular membranes. J Neurosci. 2004;24(30):6650–6658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0010-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flajolet M, Wang Z, Futter M, Shen W, Nuangchamnong N, Bendor J, et al. FGF acts as a co-transmitter through adenosine A2A receptor to regulate synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(12):1402–1409. doi: 10.1038/nn.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun CN, Cheng HC, Chou JL, Lee SY, Lin YW, Lai HL, et al. Rescue of p53 blockage by the A2A adenosine receptor via a novel interacting protein, translin-associated protein X. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(2):454–466. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun CN, Chuang HC, Wang JY, Chen SY, Cheng YY, Lee CF, et al. The A2A adenosine receptor rescues neuritogenesis impaired by p53 blockage via KIF2A, a kinesin family member. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70(8):604–621. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, Besshoh S, Arundine M, Gurd JW, et al. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor- PSD-95 protein interactions. Science. 2002;298(5594):846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cook DJ, Teves L, Tymianski M. Treatment of stroke with a PSD-95 inhibitor in the gyrencephalic primate brain. Nature. 2012;483(7388):213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature10841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ji SP, Zhang Y, Van Cleemput J, Jiang W, Liao M, Li L, et al. Disruption of PTEN coupling with 5-HT2C receptors suppresses behavioral responses induced by drugs of abuse. Nat Med. 2006;12(3):324–329. doi: 10.1038/nm1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei CJ, Li W, Chen JF. Normal and abnormal functions of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system revealed by genetic knockout studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(5):1358–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomes CV, Kaster MP, Tome AR, Agostinho PM, Cunha RA. Adenosine receptors and brain diseases: neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(5):1380–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.