Abstract

Cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) are critical front line contributors to host defense against invasive bacterial infection. These immune factors have direct killing activity toward microbes, but many pathogens are able to resist their effects. Group A Streptococcus, group B Streptococcus and Streptococcus pneumoniae are among the most common pathogens of humans and display a variety of phenotypic adaptations to resist CAMPs. Common themes of CAMP resistance mechanisms among the pathogenic streptococci are repulsion, sequestration, export, and destruction. Each pathogen has a different array of CAMP-resistant mechanisms, with invasive disease potential reflecting the utilization of several mechanisms that may act in synergy. Here we discuss recent progress in identifying the sources of CAMP resistance in the medically important Streptococcus genus. Further study of these mechanisms can contribute to our understanding of streptococcal pathogenesis, and may provide new therapeutic targets for therapy and disease prevention.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptide, LL-37, defensin, cathelicidin, Streptococcus, virulence factors, innate immunity

Introduction

The genus Streptococcus comprises some of the most common, yet potentially deadly, bacterial pathogens of humans. Medically important streptococcal species are typically carried asymptomatically, but have significant pathogenic potential if not restricted to superficial sites. Group A Streptococcus (GAS; S. pyogenes) commonly colonizes the mucosal tissues of the nasopharynx or the skin, and is estimated to cause more than 700 million cases of pharyngitis (“strep throat”) or superficial skin infections (impetigo) annually worldwide [1]. Less commonly, GAS are associated with severe invasive infections including streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis, and the pathogen is the trigger of the post-infectious immunologically-mediated syndromes of rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis [2]. Group B Streptococcus (GBS; S. agalactiae) is typically carried asymptomatically in the lower gastrointestinal tract or vaginal mucosa. Upon ascending infection of the placental membranes or during passage through the birth canal, GBS can access the newborn infant, where it is a major cause of pneumonia, sepsis and meningitis [3]. GBS is also increasingly associated with invasive infections in adult populations including pregnant women, the elderly and diabetics [4]. The pneumococcus (S. pneumoniae), which colonizes the nasal mucosa, is a major cause of mucosal infections such as otitis media and sinusitis, as well as pneumonia, sepsis in meningitis, especially at the ends of the age spectrum and throughout the developing world [5, 6]. S. mutans colonizes the mouth, where it a major contributor to tooth decay. Additional Streptococcus spp., more rarely associated with disease in humans, are pathogenic for other animal species, e.g. S. suis (swine) and S. iniae (fish).

A critical first line of host innate defense against invasive infections by pathogenic streptococci is provided by endogenous cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs). CAMPS are produced by epithelial cells and by circulating immune cells including neutrophils and macrophages, and are among the first immune effectors encountered by an invading microbe [7, 8]. CAMP expression is greatly induced during infection, it is also induced in sterile models of injury that compromise the epithelial barrier, indicating it can function a prophylactic measure against imminent pathogen invasion [9].

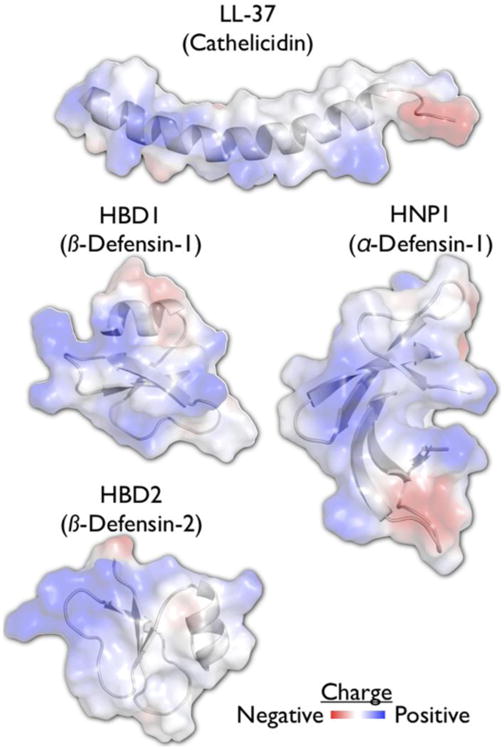

Two major classes of the CAMPs present in mammals are the cathelicidins and the defensins (Figure 1). Both represent small, cytotoxic pore-forming peptides that contain regions of strong cationic charge that intersperse solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues. This amphiphilicity is a key source of their antimicrobial activity; the positive charge attracts them to a microbe's surface and their hydrophobic surfaces insert into and permeabilize the bacterial membrane. An additional target of CAMPs is the ExPortal, an organelle dedicated to the biogenesis of secreted proteins in streptococci and entercocci [10]. Since many of the CAMP resistance mechanisms that will be discussed rely on the secretion of proteins through this system, this may represent a way to counter these resistance mechanisms. In addition to directly targeting the pathogen, CAMPs can also coordinate the immune response to infection by contributing to cytokine signaling, immune cell chemotaxis, and wound healing [11-13]. Therefore, some microbial mechanisms for counteract CAMPs can also impact these downstream immune pathways.

Figure 1. Common electrostatic properties of antimicrobial peptides.

The mature fragment of human cathelicidin, LL-37, is an α-helical peptide (pdb: 2K6O), while the defensins can have a number of different folds (pdb: 1FD3, 1E4S, 2PM1). These peptides have in common a strongly cationic face that mediates the electrostatic attraction to the cell surface of the Streptococci and other microbes.

Defensins are highly polymorphic, with numerous alleles expressed by various immune cell types. In contrast, mice and humans express only one cathelicidin: hCAMP18 (human) or mCRAMP (murine). These proteins are made of a conserved amino-terminal cathelin (protease inhibitor) domain and a highly charged alpha-helical carboxy-terminus. Cathelicidins are not antimicrobial until the cathelin pro-domain is proteolytically removed, freeing the remaining peptide, in humans named LL-37, to act against the microbe [14]. In addition to these classical CAMPs, cathelicidins and defensins, several other proteins and their degradation products are cationic and antimicrobial. These proteins include lysozyme, histones, thrombocidin, lactoferrin, cathepsins, myeloperoxidase, kininogen, and heparin-binding proteins. Many of these proteins are found in neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), web-like structures in which these cationic antimicrobials are embedded within an extruded (acidic) DNA matrix [15]. NETs can potentiate killing of extracellular microbes, which will be trapped and exposed to a higher local concentration of cathelicidin and other CAMPs. While neutrophils are critical in controlling streptococcal infections, additional cells make NET-like structures that may also function in pathogen defense [16].

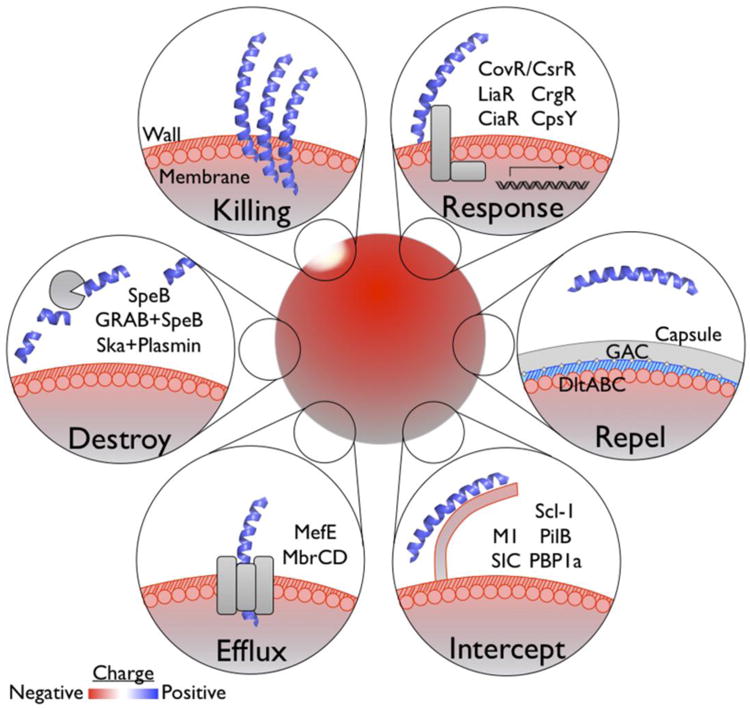

While mechanisms of resistance to cathelicidin/LL-37 or defensins do not always correlate with one another [17], many of the virulence factors the pathogens employ to evade one CAMP can be cross protective against others. Nearly any virulence factor of a pathogen may contribute, at least indirectly, to a pathogen's resistance or susceptibility to CAMPs. For example, pore-forming toxins induce cell death that can eliminate CAMP-producing cells [18], secreted DNases can facilitate escape from NETs [19], and any number of mechanisms that shield potential pathogen-associated molecular patterns can work to lessen the induction of CAMP expression via TLRs [20]. In this review, we focus primarily on molecular mechanisms that directly target CAMPs, by the common themes of repulsion, sequestration, export, and destruction (Figure 2). We further discuss how streptococcal pathogens detect and regulate their gene expression to resist these CAMPs, and emerging strategies toward combatting infection by boosting or supplementing CAMP defenses.

Figure 2. Models of streptococcal resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides.

CAMPs attracted to the cell surface form pores that disrupt membrane integrity (Killing). Pathogens, including the streptococci, are able to detect CAMPs either directly or indirectly via sensors. Detection of sub-inhibitory concentrations of CAMPs can induce resistance mechanisms protective for when higher CAMP concentrations are encountered (Response). Examples of these resistance mechanisms are cell surface modification (Repel), competitive binding (Intercept), removal or secretion (Efflux), or proteolytic inactivation (Destroy).

Repel

One of the first mechanisms recognized by which pathogens evade killing by CAMPs is directed at one of their rudimentary properties – charge. The outer leaflet of the mammalian cell contains zwitterionic phospholipids and carries little negative charge that would attract CAMPs, which protects cells from toxicity from these molecules. CAMPs are attracted to bacterial membranes, which are abundant in acidic phospholipids. Streptococci, like other Gram-positive bacteria, are additionally coated with an acidic polymer of teichoic acids on their cell well. When a bacterium can increase its net surface charge to more closely resemble the charge profile of a mammalian cell, it can decrease the affinity of cationic molecules like CAMPs to its surface. This can be accomplished by several chemical modifications possible for each layer of the cell surface: the lipid membrane, the peptidoglycan and teichoic acid-containing cell wall, and the capsular polysaccharides.

It is not yet known if any of the pathogenic streptococci can alter their lipid cell membrane in a manner providing resistance to CAMPs. Several Gram-positive pathogens have been reported to modify the acidic membrane lipid phosphatidylglycerol with the cationic amino acid, L-lysine [21], reducing the net negative charge of the membrane, thereby decreasing attraction of CAMPs. This L-lysinylation reaction is carried out by a lysyl-phosphatidylglycerol synthase encoded by mprF, a gene absent from the GAS and pneumococcal genomes. GBS do possess mprF, but deletion of the gene did not significantly alter resistance to CAMPs [22]. The mprF gene is present in the sequenced genomes of other veterinary/zoonotic pathogens including S. iniae and S. suis, but any contribution to CAMP resistance has yet to be demonstrated.

The Gram-positive cell membrane is covered by the cell wall, a rigid porous mesh composed of heavily cross-linked peptidoglycan. The backbone of peptidoglycan consists of N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid linked by short peptides. Two modifications streptococci can make to this base structure are N-deacetylation of the N-acetylglucosamine subunit, carried out by PgdA, and O-acetylation of the N-acetylmuramic acid, catalyzed by OatA (Adr). Despite increasing surface charge and lysosome resistance, N-deacetylation does not alter CAMP resistance in S. pneumoniae [23] nor S. suis [24]. O-acetylation also increases surface charge and decreases binding of cationic proteins. However, for S. iniae this did not translate to altered CAMP susceptibility [25]. In S. pneumonia, O-acetylation does increase resistance to lysosome, which is cationic [26], but the effect on CAMP resistance was not evaluated. The same N-deacetylation and O-acetylation mechanisms confer CAMP resistance in other species, suggesting they may still act in streptococci in manners yet to be evaluated.

Teichoic acids make up a second major component of the Gram-positive cell wall. These glycerophosphate polymers are anchored to the peptidoglycan and cell membrane, and like both, is also acidic. The dlt operon encodes enzymes mediating D-alanylation of wall teichoic acids, a modification nearly ubiquitous among Gram-positive pathogens. The highly cationic side chain of alanine increases cell surface charge; cell wall density is concurrently increased by a mechanism that is not yet entirely clear [22]. Together, these changes increase resistance to CAMPs, as well as bacteriocins, lysozyme, acid, and NETs, and thereby the major immune cells producing these antimicrobial factors, neutrophils [27-29]. Thus, dlt is important for the virulence of GAS [29], GBS [30], S. pneumoniae [27], S. suis [31], and S. mutans [32]. The conservation of the phenotype of dlt mutants between these species clearly illustrates its advantageous role in direct resistance to CAMPs, however, some care must be taken to avoid over interpreting results from mutations like this that alter fundamental cell structures. For example, the increased CAMP susceptibility of GAS dlt mutants may not be solely a consequence of failing to modify cell techoic acids, but also due to lower expression levels of M protein and SIC [33], two important virulence factors that also contribute to CAMP resistance in this species [34, 35].

The third component of the streptococcal cell wall is the Lancefield group-specific carbohydrate. These carbohydrates compose up to half the cell wall by weight, and provide the basis for the serological separation of streptococcal groups. In groups A and C streptococci, the antigen consists of a polyrhamnose backbone and immunodominant side-chain specific to each group. The functional role of these carbohydrates had long remained a mystery, but recently, it was shown that the group A carbohydrate of GAS has an N-acetylglucosamine side-chain which blocks LL-37 binding, thereby providing resistance to CAMPs as well as killing by neutrophils and NETs [36].

Another method to repel CAMPs is the recruitment of factors to increase the net charge of the bacteria surface, rather than to direct modify it. An example of this mechanism can be found in S. pneumoniae where the LytA protein decorates the bacterial surface with highly charged choline [37]. This masking could decrease attraction of CAMPs, as in the respiratory pathogen Haemophilus influenzae, recruitment of choline to its surface, albeit by a different mechanism, does afford significant protection against CAMPs [38]. Separate from providing protection from CAMPs, pneumococcal cholate binding does contribute NET resistance [28]. Lipoteichoic acid D-alanylation did not affect NET trapping of pneumococci, but did provide the pathogen protection against killing by CAMPs embedded within the NET [28].

The most distal surface on many Gram-positive bacteria is an exopolysaccharide capsule. This family of critical virulence factors shields the bacterial surface and promotes resistance to phagocytosis and complement [39]. This also masks susceptible underlying cell layers from CAMP action, as GAS lacking their hyaluronic acid capsule are more susceptible to CAMPs, neutrophils, and NETs [40]. Mutations altering capsule can similarly sensitize S. iniae [41] and S. pneumoniae [42] to killing by CAMPs. Interestingly, capsule expression can instead sensitize a bacterium to killing by some CAMPs; as some strains of encapsulated S. pneumoniae are more sensitive to defensins [43], possibly a result of increased attraction of CAMPs to the bacterium by a particularly anionic capsule composition. Yet, during infection this interaction could also translate into a virulence mechanism; several pathogens including S. pneumoniae dynamically shed their negatively charged capsular polysaccharide in vivo, which can intervene and neutralize CAMPs before they can bind the underlying cell structures [42]. This mechanism of binding CAMPs before they can find their cellular target introduces the second method of protection against CAMPs; interception.

Intercept

Streptococci decorate their outer surface with numerous proteins that inhibit immune functions ranging from phagocytosis to cytokine signaling. Some of these proteins encode for more than one activity, and one of the common accessory functions of these proteins is providing CAMP resistance. One of the earliest identified of these proteins it the serum inhibitor of complement (SIC), first characterized for its role in protection against killing by the membrane attack complex [44], but later found to also bind and inhibit killing by defensins and LL-37 [45]. Consequently, SIC is required for the full virulence of GAS [35]. Several proteins with homology to SIC have similar activity, including another GAS protein, distantly related to SIC (DRS) [46], and the S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (GCS/GGS) protein DrsG [47].

One of the major surface proteins of GAS is the fimbrial M protein. This immunodominant surface anchored protein is multifunctional during infection, and can varyingly promote or inhibit adhesion and invasion of mammalian cells, inhibit complement and opsonization, induce inflammation, and act as a superantigen [48]. These broad activities are not universal among isolates, due to both a varying modular arrangement of domains and a region of hyper-variability, which serves as the basis for the serological classification of isolates from this species. One M protein variant encoded by the isolates most commonly associated with infection, M1, can directly bind CAMPs like LL-37 and mCRAMP [34]. This sequestration can significantly increase the resistance of M1 GAS Strains to CAMPs, and such isolates with higher CAMP resistance are more commonly associated with severe disease [34]. Another common M-type, M49, did not bind CAMPs, but since more than one hundred M-types have been identified, but it is not yet clear how pervasive M-mediated CAMP resistance might be among GAS.

Another major cell surface structure provides CAMP resistance for GBS through an interception mechanism: the pilus. GBS pili have been primarily characterized for their role in adhesion, but the major pilin subunit of this complex, PilB, can also sequester CAMPs like LL-37 and mCRAMP, [49]. As with M protein and SIC, the surface charge of the bacteria is not appreciably altered by the presence or absence of the protein. Also like M protein and SIC, inhibition of CAMPs seems to be highly variable and not all isolates of GAS and GBS make pilin, and not all pilin that have this activity [50]. The GBS penicillin binding protein PBP1a also likely acts through competitive binding [51]. PBPs are surface localized and often important for cell well biosynthesis, but many have unknown or unrelated cellular roles. PBP1a itself is not necessary for critical cellular pathways such as cell wall biosynthesis, as a mutant can be made and is fully viable, but has a virulence defect in vivo [52]. This attenuation may be largely due to a vulnerability to CAMPs, since a PBP1a mutant is more sensitive to killing by LL-37, CRAMP, and defensin [51]. Since all of these proteins have other clear virulence functions, CAMP resistance might be considered to be more of an accessory function secondary to their other contributions to the cell, similar to many members of the next category of CAMP resistance factors, those that affect export.

Export

Efflux pumps are an important contributor to virulence in several Gram-positive pathogens. However, efflux pumps that provide resistance to CAMPs have most extensively been studied in Gram-negative pathogens [53]. S. pneumoniae encodes an efflux pump for macrolides, MefE, that also provides protection against defensins, LL-37, and CRAMP [54]. This cross-protection would suggest that many such efflux pumps might provide resistance, and S. pneumoniae encodes several additional possible transporters [55]. Mutation of some of these putative transporters increases pneumococcal CAMP susceptibility, suggesting they are expressed and active [56]. The homolog of one of these, SP0912-0913 (MbrCD) has also been found in S. mutans to contribute to resistance against defensins [57]. While not well studied in other streptococci, many of these genes are found in additional species; if they are confirmed to act as CAMP efflux pumps, this could represent significant contributor to CAMP resistance throughout the genus Streptococcus.

Destroy

One last, very direct, mechanism for resisting killing by CAMPs is to destroy them. This can be accomplished by secreted proteases that hydrolyze the peptides before they can exert their cytotoxic activities. Gram-positive pathogens, in particular, are prolific secretors of proteases that target host proteins. The factors can promote virulence by inactivating antibodies, cytokines, complement proteins, autophagy machinery, and many other immune factors, including CAMPs. However, targeting of CAMPs is not a universal property of even highly active bacterial proteases, suggesting these molecules are not generally protease-sensitive; the virulence factor needs to specifically target the CAMP. For instance, even though the IgG protease of GAS, Mac/IdeS, is very highly expressed, it provides no resistance to LL-37 [58].

However, GAS does secrete at least one protease active against CAMPs: SpeB. This intensively studied cysteine protease has been found to cleave numerous host proteins in both extracellular and intracellular locations [59, 60] including the CAMPs LL-37 [61] and β-defensin [62]. In addition to directly hydrolyzing CAMPs into inactive or less active forms, SpeB can target other factors in ways that interfere with killing. SpeB degradation of tissue proteoglycans releases glycosaminoglycans like dermatan sulfate, a charged molecule which can bind and inhibit CAMPs including α-defensin [63] and LL-37 [64].

SpeB-mediated CAMP protection can be amplified even further through the activity of a second GAS virulence factor, G-related α2-macroglobulin- binding protein (GRAB) [65]. This surface protein forms a complex with the circulating α2-macroglobulin, an abundant broad-spectrum protease inhibitor with numerous roles in maintaining homeostasis. Proteases trapped by α2-macroglobulin lose the ability to process large substrates, however, peptides small enough to penetrate the α2-macroglobulin:GRAB:SpeB complex are still cleaved [65]. Thus, this complex can both retain SpeB on the bacterial surface where it can be most efficacious against CAMPs, while also maintaining the proteolytic activity of SpeB, and possibly even amplifying it by antagonizing hydrolysis of other possible substrates of SpeB.

Instead of producing its own proteases, a bacterial pathogen can also recruit and utilize host proteases. The virulence factor streptokinase (Ska) allows GAS to recruit and activate host plasminogen on the bacterial surface [66]. Recruitment of plasminogen is relatively common strategy of pathogens; plasminogen is the precursor zymogen of plasmin, a serine protease that degrades fibrin clots, connective tissue, and extracellular matrix. Plasmin activated by streptokinase can contribute to the virulence of GAS by dissolving fibrin deposits to promote dissemination throughout host tissue [66]. In addition to this activity targeting the host fibrinolytic system, plasmin activated by streptokinase is able to cleave the cathelicidins LL-37 and CRAMP, which increases the bacterium's resistance to these CAMPs [67].

The role of proteases in providing CAMP resistance to other streptococcal species is not yet fully clear. Other important human pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Porphyromonas gingivalis all make proteases that target CAMPs [61]. Therefore, even though obvious homologs of SpeB are not found in the other pathogenic streptococci, common activity from dissimilar and unrelated proteases suggest that other proteases may have a CAMP neutralizing function. Obvious candidates would be proteases that are highly expressed and are secreted. For GBS, this would include ScpB and CspA, and for S. pneumoniae, the serine protease PrtA. In addition to making their own CAMP proteases, streptococci other than GAS may utilize streptokinase-activated plasmin for this purpose; GBS, GCS, and pneumococcus can all activate plasminogen [68].

One caveat for a pathogen resisting CAMPs through proteolysis is the possibility of working at cross-purposes and inactivating other important virulence factors. In addition to cleaving CAMPs, SpeB also degrades streptokinase, M1 protein, and host plasminogen; consequently, SpeB can be a barrier to invasive disease [69]. These proteins all contribute to CAMP resistance, thus providing a very clear example of the shared benefits and liabilities of SpeB expression. Since it is highly expressed in vivo and maintained within the GAS pan-genome, the virulence tradeoff to SpeB is context-dependent. Nonetheless, SpeB is be observed to colocalize with LL-37 in tissue samples from patients with invasive GAS infection, suggesting it may remain a dominant virulence factor for the degradation of CAMPs [70].

Another consideration for the effect of bacterial proteases on CAMPs is the possibility of crosstalk with their activating proteases. As an example, cathelicidin is synthesized as a propeptide and requires protease cleavage to release the antimicrobial carboxy-terminus (LL-37 and related peptides). Cleavage of a CAMP by a microbial protease in the wrong site could end up liberating a CAMP, rather than destroying one. Furthermore, the remaining amino-terminal cathelin domain of cathelicidin has homology with cystatin family of cysteine protease inhibitors [14]. Since this will be present in the same tissue as the active CAMP, it could inhibit microbial attempts to destroy CAMPs. Additionally, protease inhibitors in general are some of the most common circulating proteins. In an infection context, the presence of inhibitors that can target bacterial proteases could dampen the ability of bacteria to destroy CAMPs, despite experiments that readily observe hydrolysis of CAMPs in vitro [9].

Regulation

The ability of a microbe to respond to environmental stimuli and stressors can allow expression of costly or conditionally detrimental proteins in only the contexts that are beneficial for the microbe. Response regulators sensitive to CAMPs that allow a pathogen to selectively induce any of the resistance mechanisms mentioned above could greatly increase the adaptability and virulence potential. The archetype of this response is the PhoPQ two-component regulatory system of Salmonella. The sensor PhoQ contains an acidic patch that binds CAMPs, subsequently signaling through PhoP to induce CAMP-protective cell surface modifications [71]. It is unknown whether pathogenic strepococci encode sensors that directly recognize CAMPs, but several response regulator components are responsive to CAMPs.

The GAS CovRS (CsrRS) two-component system is the most characterized of these response regulators. CovRS-regulated genes are activated by the CAMP LL-37 and repressed by high Mg2+ [72], similar to the PhoPQ paradigm where CAMP activates and Mg2+ represses gene expression [71]. CovS is the sensor of this pair, and CovR a transcriptional repressor that is inactivated by CovS signaling [73]. Mutation of CovR and CovS, singly or in combination, appears to only modestly alter resistance of GAS to the CAMP LL-37, a difference that was significant in one study [74] but not another [75]. Nonetheless, virulence factor induction through LL-37 dependent CovRS signaling is protective during infection, indicating it may be more potent at counteracting other immune mechanisms [72, 76]. Clear homologs of CovRS are present in other streptococci including GBS where it shares the same name; their role in the detection of and resistance to CAMPs is not yet clear, but these two-component systems similarly regulate virulence factor expression and impact pathogenesis [77].

Which CovRS-regulated proteins contribute to CAMP resistance is not fully clear; 10% of the entire GAS genome is differentially regulated by CovRS [78]. Many CovRS-regulated genes encode virulence factors, including several known to provide resistance to CAMPs. SpeB expression is abolished in a CovRS mutant, while SIC and the operon encoding hyaluronic acid capsule biosynthesis (has) are more highly expressed. The counterbalance of these CAMP resistance mechanisms might explain why CovRS mutants are not more highly sensitive to CAMPs than mutants for any particular resistance factors, like M1, SIC, capsule, or SpeB. This interplay is further complicated by SpeB degradation of other CAMP resistance factors, counterbalanced by the naturally occurring CovS mutants that arise during invasive infection [79].

CovRS is active in GBS, but it is unknown whether it is also responsive to CAMPs. However, GBS do induce several known and putative CAMP resistance factors in response to sub-inhibitory concentrations of LL-37 [56]. Two different two-component system response regulators are known to be involved, LiaR [80] and CiaR [81]. Both systems induce resistance to CAMPs like LL-37 and CRAMP, but it is not known whether the sensor kinases of the systems, LiaS and CiaS, directly detect the CAMPs or whether they transduce signals downstream of some effect that CAMPs have on the cell or its environment. LiaR-mutant bacteria are less piliated, express less of the penicillin-binding protein PbP2b, and less peptidoglycan cross-linking enzymes, which could all relate to this CAMP susceptibility [80]. LiaRS is also active in S. pneumoniae and S. mutans; it is not known whether it mediates CAMP resistance in these species, but it shows sensitivity to many of the same stressors as the GBS system [82, 83]. Genes regulated by CiaR are more cryptic in function, but include several proteases, which might be responsible for increased CAMP resistance if they were capable of degrading the molecules. However, CiaR also regulates resistance to stresses like hydrogen peroxide and hypoclorite, which could suggest a more broad regulation of protective modifications of the cell surface. Another regulator of GAS, CrgR, strongly increases resistance of GAS to the murine CRAMP [84]. While the factors mediating this resistance are not known, this mutant only outcompetes wild-type GAS in the presence of CRAMP and during infection CRAMP knockout mice, indicating the CrgR virulence phenotype is highly specific to CAMP resistance.

Several regulators important for CAMP resistance in other species are present in the pathogenic streptococci but their contribution to virulence is not yet fully characterized. Staphylococcus epidermidis uses ApsXRS to induce the dlt operon and MprF in response to defensin and LL-37 [85]. dlt and MprF also contribute to CAMP resistance in many streptococcal species, and clear homologs to the Aps system are present in some of the strains. Similarly, the BceRS (MbrAB) bacitracin sensor and response regulator can detect and initiate a protective response against CAMPs for B. subtilis [86]. This system is found in several streptococcal pathogens. BceRS has been studied in S. mutans where it was still found to work against bacitracin, but no cross-protection against other CAMPs was found [57]. The CpsY (MetR/MtaR) regulator of S. iniae modulates expression of genes involved in peptidoglycan acetylation [25]. Mutation of CpsY led to an increase in surface charge and susceptibility to lysozyme, though no difference in LL-37 killing was observed [25]. Since decreased surface charge generally inhibits CAMP attraction, this could still mediate resistance to other CAMPs, especially if a CpsY inducer were uncovered that could lead to greater induction of this pathway.

Conclusion

The pathogenic streptococci employ a large, often redundant, array of CAMP resistance mechanisms (Table 1). While highlighting a persistent evolutionary selective pressure to escape CAMP killing, it is telling that streptococci have not found a complete solution; the high CAMP concentrations and diverse CAMP repertoire that are detected in vivo [87] still restrict streptococci employing their full complement of resistance mechanisms in the vast majority of host-pathogen encounters. Since CAMPs are ancient molecules present in all forms of life and remain critical in the human immune system, high level-resistance, as seen for most modern pharmaceutical antibiotics, just might not be achievable for a bacterium. This recognition suggests enhancing endogenous CAMP function could provide an attractive avenue for treatment of bacterial infections.

Table 1. Summary of the CAMP resistance mechanisms of streptococcal pathogens.

GAS, group A Streptococcus; GBS, group B Streptococcus; GCS, Group C (and G) Streptococcus; SPN, Streptococcus pneumonia; Sm, Streptococcus mutans, Ss, Streptococcus suis.

| Category | Specific Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|

| REPEL | ||

| DltABC | Lipotechoic acid D-alanylation | GAS [29], GBS [30], SPN [27], Ss [31], Sm [32] |

| HasABC | Hyaluronic acid (Capsule) | GAS [40] |

| GacA-L | Glucuronic-B-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine (Group A carbohydrate) | GAS [36] |

| INTERCEPT | ||

| M1 | Competitive binding | GAS [34] |

| SIC / DRS | Competitive binding | GAS [45] [46], GCS [47] |

| Scl-1 | Competitive binding | GAS [97] |

| PilB | Competitive binding | GBS [49] |

| PBP1a | Competitive binding | GBS [51] |

| Dermatan sulfate | Competitive binding by host proteoglycans released by bacterial proteases | GAS [63] |

| EFFLUX | ||

| SP0785-7 | ABC transporter (putative) | Sp [56] |

| MbrCD | ABC transporter (putative) | Sm [57] Sp [56] |

| MefE | Efflux pump | Sp [54] |

| DESTROY | ||

| SpeB | Direct proteolysis | GAS [61] |

| GRAB | Protease recruitment/redirection | GAS [65] |

| Ska | Activation of proteolysis by plasmin | GAS [67] |

Low levels of defensin and LL-37 correlate with atopic dermatitis and susceptibility to bacterial infection [87]. Mice deficient in the cathelicidin CRAMP are hyper-susceptible to GAS infection [84], while transgenic mice expressing additional CAMP are more resistant to infection [88, 89]. Therefore, boosting expression of endogenous CAMPs might be seen to have both prophylactic and therapeutic potential in combating streptococcal infection. Vitamin D receptor signaling induces expression of human cathelicidin, camp, and β-defensin, defB2, but not the murine cramp [90, 91]. This pathway can be further amplified by TLR signaling in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns [20] or during injury, likely in response to damage-associated molecular patterns [92]. Similarly, infection can induce HIF, a global regulator in response to hypoxia that is important for CRAMP expression [93-95]. HIF can also be boosted pharmacologically, boosting cathelicidin expression, and providing a potential avenue for adjunctive treatment of invasive streptococcal infections [96].

Highlights.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) protect against bacterial infection

Cell surface modifications promote CAMP evasion by streptococcal pathogens

Additional CAMP resistance occurs through sequestration, removal and destruction

Understanding CAMP sensitivity/resistance may reveal new therapeutic approaches to streptococcal infection

Acknowledgments

CNL is an A. P. Giannini Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow. Streptococcal pathogenesis and antimicrobial peptide research in the Nizet Lab is supported through NIH grants from NIAID, NICHD, NHLBI and NIAMS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker MJ, Barnett TC, McArthur JD, Cole JN, Gillen CM, Henningham A, Sriprakash KS, Sanderson-Smith ML, Nizet V. Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of group a Streptococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:264–301. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00101-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker CJ. The spectrum of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Vaccine. 2013;31(Suppl 4):D3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sendi P, Johansson L, Norrby-Teglund A. Invasive group B streptococcal disease in non-pregnant adults : a review with emphasis on skin and soft-tissue infections. Infection. 2008;36:100–111. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-7251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch JP, 3rd, Zhanel GG. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and strategies for prevention, Sem Resp. Crit Care Med. 2009;30:189–209. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drijkoningen JJ, Rohde GG. Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 5):45–51. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bals R, Wang X, Zasloff M, Wilson JM. The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad antimicrobial activity at the airway surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9541–9546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolzenberg ED, Anderson GM, Ackermann MR, Whitlock RH, Zasloff M. Epithelial antibiotic induced in states of disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8686–8690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorschner RA, Pestonjamasp VK, Tamakuwala S, Ohtake T, Rudisill J, Nizet V, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH, Gallo RL. Cutaneous injury induces the release of cathelicidin anti-microbial peptides active against group A Streptococcus. J Invest Derm. 2001;117:91–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vega LA, Caparon MG. Cationic antimicrobial peptides disrupt the Streptococcus pyogenes ExPortal. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:1119–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heilborn JD, Nilsson MF, Kratz G, Weber G, Sørensen O, Borregaard N, Ståhle-Bäckdahl M. The cathelicidin anti-microbial peptide LL-37 is involved in re-epithelialization of human skin wounds and is lacking in chronic ulcer epithelium. J Invest Derm. 2003;120:379–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang D, Chen Q, Schmidt AP, Anderson GM, Wang JM, Wooters J, Oppenheim JJ, Chertov O. LL-37, the neutrophil granule–and epithelial cell–derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor–like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1069–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J, Mookherjee N, Wee K, Bowdish DME, Pistolic J, Li Y, Rehaume L, Hancock REW. Host defense peptide LL-37, in synergy with inflammatory mediator IL-1β, augments immune responses by multiple pathways. J Immunol. 2007;179:7684–7691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaiou M, Nizet V, Gallo RL. Antimicrobial and protease inhibitory functions of the human cathelicidin (hCAP18/LL-37) prosequence. J Invest Derm. 2003;120:810–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Köckritz-Blickwede M, Goldmann O, Thulin P, Heinemann K, Norrby-Teglund A, Rohde M, Medina E. Phagocytosis-independent antimicrobial activity of mast cells by means of extracellular trap formation. Blood. 2008;111:3070–3080. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habets MGJL, Rozen DE, Brockhurst MA. Variation in Streptococcus pneumoniae susceptibility to human antimicrobial peptides may mediate intraspecific competition. Proc Royal Soc B: Biol Sci. 2012;279:3803–11. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1118. 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmer AM, Timmer JC, Pence MA, Hsu LC, Ghochani M, Frey TG, Karin M, Salvesen GS, Nizet V. Streptolysin O promotes group A Streptococcus immune evasion by accelerated macrophage apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:862–871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804632200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumby P, Barbian KD, Gardner DJ, Whitney AR, Welty DM, Long RD, Bailey JR, Parnell MJ, Hoe NP, Adams GG. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1679–1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, Ochoa MT, Schauber J, Wu K, Meinken C, Kamen DL, Wagner M, Bals R, Steinmeyer A, Zügel U, Gallo RL, Eisenberg D, Hewison M, Hollis BW, Adams JS, Bloom BR, Modlin RL. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst CM, Staubitz P, Mishra NN, Yang SJ, Hornig G, Kalbacher H, Bayer AS, Kraus D, Peschel A. The bacterial defensin resistance protein mprF consists of separable domains for lipid lysinylation and antimicrobial peptide repulsion. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5:e1000660. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saar-Dover R, Bitler A, Nezer R, Shmuel-Galia L, Firon A, Shimoni E, Trieu-Cuot P, Shai Y. D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids confers resistance to cationic peptides in group B Streptococcus by increasing the cell wall density. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8:e1002891. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollmer W, Tomasz A. Peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase, a putative virulence factor in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2002;70:7176–7178. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7176-7178.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fittipaldi N, Sekizaki T, Takamatsu D, De La Cruz Domínguez-Punaro M, Harel J, Bui NK, Vollmer W, Gottschalk M. Significant contribution of the pgdA gene to the virulence of Streptococcus suis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:1120–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen JP, Neely MN. CpsY influences Streptococcus iniae cell wall adaptations Iimportant for neutrophil intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1707–1715. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00027-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crisóstomo MI, Vollmer W, Kharat AS, Inhülsen S, Gehre F, Buckenmaier S, Tomasz A. Attenuation of penicillin resistance in a peptidoglycan O-acetyl transferase mutant of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1497–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovács M, Halfmann A, Fedtke I, Heintz M, Peschel A, Vollmer W, Hakenbeck R, Brückner R. A functional dlt operon, encoding proteins required for incorporation of D-alanine in teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria, confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5797–5805. doi: 10.1128/JB.00336-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wartha F, Beiter K, Albiger B, Fernebro J, Zychlinsky A, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Capsule and D-alanylated lipoteichoic acids protect Streptococcus pneumoniae against neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1162–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristian SA, Datta V, Weidenmaier C, Kansal R, Fedtke I, Peschel A, Gallo RL, Nizet V. D-alanylation of teichoic acids promotes group a streptococcus antimicrobial peptide resistance, neutrophil survival, and epithelial cell invasion. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6719–6725. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.19.6719-6725.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poyart C, Pellegrini E, Marceau M, Baptista M, Jaubert F, Lamy MC, Trieu-Cuot P. Attenuated virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae deficient in D-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is due to an increased susceptibility to defensins and phagocytic cells. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1615–1625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fittipaldi N, Sekizaki T, Takamatsu D, Harel Je, de la Cruz Domínguez-Punaro M, Von Aulock S, Draing C, Marois C, Kobisch Mn, Gottschalk M. D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acid contributes to the virulence of Streptococcus suis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3587–3594. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01568-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazda Y, Kawada-Matsuo M, Kanbara K, Oogai Y, Shibata Y, Yamashita Y, Miyawaki S, Komatsuzawa H. Association of CiaRH with resistance of Streptococcus mutans to antimicrobial peptides in biofilms. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:124–135. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox KH, Ruiz-Bustos E, Courtney HS, Dale JB, Pence MA, Nizet V, Aziz RK, Gerling I, Price SM, Hasty DL. Inactivation of DltA modulates virulence factor expression in Streptococcus pyogenes. PloS One. 2009;4:e5366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauth X, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, McNamara CW, Myskowski S, Zinkernagel AS, Beall B, Ghosh P, Gallo RL, Nizet V. M1 protein allows group A streptococcal survival in phagocyte extracellular traps through cathelicidin inhibition. J Innate Immun. 2009;1:202–214. doi: 10.1159/000203645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pence MA, Rooijakkers SH, Cogen AL, Cole JN, Hollands A, Gallo RL, Nizet V. Streptococcal inhibitor of complement promotes innate immune resistance phenotypes of invasive M1T1 group A Streptococcus. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:587–595. doi: 10.1159/000317672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Sorge Nina M, Cole Jason N, Kuipers K, Henningham A, Aziz Ramy K, Kasirer-Friede A, Lin L, Berends Evelien TM, Davies Mark R, Dougan G, Zhang F, Dahesh S, Shaw L, Gin J, Cunningham M, Merriman Joseph A, Hütter J, Lepenies B, Rooijakkers Suzan HM, Malley R, Walker Mark J, Shattil Sanford J, Schlievert Patrick M, Choudhury B, Nizet V. The classical lancefield antigen of group A Streptococcus is a virulence determinant with implications for vaccine design. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swiatlo E, Champlin FR, Holman SC, Wilson WW, Watt JM. Contribution of choline-binding proteins to cell surface properties of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2002;70:412–415. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.412-415.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lysenko ES, Gould J, Bals R, Wilson JM, Weiser JN. Bacterial phosphorylcholine decreases susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37/hCAP18 expressed in the upper respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1664–1671. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1664-1671.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wessels MR, Moses AE, Goldberg JB, DiCesare TJ. Hyaluronic acid capsule is a virulence factor for mucoid group A streptococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:8317–8321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cole JN, Pence MA, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, Hollands A, Gallo RL, Walker MJ, Nizet V. M protein and hyaluronic acid capsule are essential for in vivo selection of covRS mutations characteristic of invasive serotype M1T1 group A Streptococcus. MBio. 2010;1:e00191–00110. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00191-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchanan JT, Stannard JA, Lauth X, Ostland VE, Powell HC, Westerman ME, Nizet V. Streptococcus iniae phosphoglucomutase is a virulence factor and a target for vaccine development. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6935–6944. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6935-6944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llobet E, Tomas JM, Bengoechea JA. Capsule polysaccharide is a bacterial decoy for antimicrobial peptides. Microbiology. 2008;154:3877–3886. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beiter K, Wartha F, Hurwitz R, Normark S, Zychlinsky A, Henriques-Normark B. The capsule sensitizes Streptococcus pneumoniae to α-defensins human neutrophil proteins 1 to 3. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3710–3716. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01748-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Åkesson P, Sjöholm AG, Björck L. Protein SIC, a novel extracellular protein of Streptococcus pyogenes interfering with complement function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1081–1088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frick IM, Åkesson P, Rasmussen M, Schmidtchen A, Björck L. SIC, a secreted protein of Streptococcus pyogenes Tthat inactivates antibacterial peptides. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16561–16566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernie-King BA, Seilly DJ, Binks MJ, Sriprakash KS, Lachmann PJ. Streptococcal DRS (distantly related to SIC) and SIC inhibit antimicrobial peptides, components of mucosal innate immunity: a comparison of their activities. Microb Infect. 2007;9:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smyth D, Cameron A, Davies MR, McNeilly C, Hafner L, Sriprakash S, McMillan DJ. DrsG from Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis inhibits the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Infect Immun. 2014;82:2337–44. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01411-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh P. Bacterial Adhesion. Springer; 2011. The nonideal coiled coil of M protein and its multifarious functions in pathogenesis; pp. 197–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maisey HC, Quach D, Hensler ME, Liu GY, Gallo RL, Nizet V, Doran KS. A group B streptococcal pilus protein promotes phagocyte resistance and systemic virulence. FASEB J. 2008;22:1715–1724. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-093963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papasergi S, Brega S, Mistou MY, Firon A, Oxaran V, Dover R, Teti G, Shai Y, Trieu-Cuot P, Dramsi S. The GBS PI-2a pilus Is required for virulence in mice neonates. PloS One. 2011;6:e18747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton A, Popham DL, Carl DJ, Lauth X, Nizet V, Jones AL. Penicillin-binding protein 1a promotes resistance of group B streptococcus to antimicrobial peptides. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6179–6187. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones AL, Mertz RH, Carl DJ, Rubens CE. A streptococcal penicillin-binding protein is critical for resisting innate airway defenses in the neonatal lung. J Immunol. 2007;179:3196–3202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shafer WM, Qu XD, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1829–1833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zähner D, Zhou X, Chancey ST, Pohl J, Shafer WM, Stephens DS. Human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 induces MefE/Mel-mediated macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3516–3519. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01756-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoskins J, Alborn WE, Arnold J, Blaszczak LC, Burgett S, DeHoff BS, Estrem ST, Fritz L, Fu DJ, Fuller W, Geringer C, Gilmour R, Glass JS, Khoja H, Kraft AR, Lagace RE, LeBlanc DJ, Lee LN, Lefkowitz EJ, Lu J, Matsushima P, McAhren SM, McHenney M, McLeaster K, Mundy CW, Nicas TI, Norris FH, O' Gara M, Peery RB, Robertson GT, Rockey P, Sun PM, Winkler ME, Yang Y, Young-Bellido M, Zhao G, Zook CA, Baltz RH, Jaskunas SR, Rosteck PR, Skatrud PL, Glass JI. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5709–5717. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5709-5717.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Majchrzykiewicz JA, Kuipers OP, Bijlsma JJE. Generic and specific adaptive responses of Streptococcus pneumoniae to challenge with three distinct antimicrobial peptides, bacitracin, LL-37, and nisin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:440–451. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00769-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ouyang J, Tian XL, Versey J, Wishart A, Li YH. The BceABRS four-component system regulates the bacitracin-induced cell envelope stress response in Streptococcus mutans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3895–3906. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01802-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okumura CYM, Anderson EL, Döhrmann S, Tran DN, Olson J, von Pawel-Rammingen U, Nizet V. IgG Protease Mac/IdeS is not essential for phagocyte resistance or mouse virulence of M1T1 group A Streptococcus. MBio. 2013;4:e00499–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00499-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnett TC, Liebl D, Seymour LM, Gillen CM, Lim JY, LaRock CN, Davies MR, Schulz BL, Nizet V, Teasdale RD. The globally disseminated M1T1 clone of group A Streptococcus evades autophagy for intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson DC, Garbe J, Collin M. Cysteine proteinase SpeB from Streptococcus pyogenes- a potent modifier of immunologically important host and bacterial proteins. Biol Chem. 2011;392:1077–1088. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidtchen A, Frick IM, Andersson E, Tapper H, Björck L. Proteinases of common pathogenic bacteria degrade and inactivate the antibacterial peptide LL-37. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:157–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frick IM, Nordin SL, Baumgarten M, Morgelin M, Schmidtchen OE, Olin AI, Egesten A. Constitutive and inflammation-dependent antimicrobial peptides produced by epithelium Are differentially processed and inactivated by the commensal Finegoldia magna and the pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes. J Immunol. 2011;187:4300–4309. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmidtchen A, Frick IM, Björck L. Dermatan sulphate is released by proteinases of common pathogenic bacteria and inactivates antibacterial α-defensin. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:708–713. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baranska-Rybak W, Sonesson A, Nowicki R, Schmidtchen A. Glycosaminoglycans inhibit the antibacterial activity of LL-37 in biological fluids. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:260–265. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nyberg P, Rasmussen M, Björck L. α2-Macroglobulin-proteinase complexes protect Streptococcus pyogenes from killing by the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52820–52823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun H, Ringdahl U, Homeister JW, Fay WP, Engleberg NC, Yang AY, Rozek LS, Wang X, Sjobring U, Ginsburg D. Plasminogen is a critical host Ppathogenicity factor for group A streptococcal infection. Science. 2004;305:1283–1286. doi: 10.1126/science.1101245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hollands A, Gonzalez D, Leire E, Donald C, Gallo RL, Sanderson-Smith M, Dorrestein PC, Nizet V. A bacterial pathogen co-opts host plasmin to resist killing by cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40891–40897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuusela P, Ullberg M, Saksela O, Kronvall G. Tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated activation of plasminogen on the surface of group A, C, and G streptococci. Infect Immun. 1992;60:196–201. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.196-201.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cole JN, McArthur JD, McKay FC, Sanderson-Smith ML, Cork AJ, Ranson M, Rohde M, Itzek A, Sun H, Ginsburg D. Trigger for group A streptococcal M1T1 invasive disease. FASEB J. 2006;20:1745–1747. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5804fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johansson L, Thulin P, Sendi P, Hertzen E, Linder A, Akesson P, Low DE, Agerberth B, Norrby-Teglund A. Cathelicidin LL-37 in severe Streptococcus pyogenes soft tissue infections in humans. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3399–3404. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01392-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bader MW, Sanowar S, Daley ME, Schneider AR, Cho U, Xu W, Klevit RE, Le Moual H, Miller SI. Recognition of antimicrobial peptides by a bacterial sensor kinase. Cell. 2005;122:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gryllos I, Tran-Winkler HJ, Cheng MF, Chung H, Bolcome R, Lu W, Lehrer RI, Wessels MR. Induction of group A Streptococcus virulence by a human antimicrobial peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16755–16760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803815105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dalton TL, Scott JR. CovS inactivates CovR and is required for growth under conditions of general stress in Streptococcus pyogenes. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3928–3937. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3928-3937.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Froehlich BJ, Bates C, Scott JR. Streptococcus pyogenes CovRS Mediates Growth in iron starvation and in the presence of the human cationic antimicrobial peptide LL-37. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:673–677. doi: 10.1128/JB.01256-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hollands A, Pence MA, Timmer AM, Osvath SR, Turnbull L, Whitchurch CB, Walker MJ, Nizet V. Genetic switch to hypervirulence reduces colonization phenotypes of the globally disseminated group A Streptococcus M1T1 clone. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:11–19. doi: 10.1086/653124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tran-Winkler HJ, Love JF, Gryllos I, Wessels MR. Signal transduction through CsrRS confers an invasive phenotype in group A Streptococcus. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7:e1002361. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lamy MC, Zouine M, Fert J, Vergassola M, Couve E, Pellegrini E, Glaser P, Kunst F, Msadek T, Trieu-Cuot P. CovS/CovR of group B streptococcus: a two-component global regulatory system involved in virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1250–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Graham MR, Smoot LM, Migliaccio CAL, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Porcella SF, Federle MJ, Adams GJ, Scott JR, Musser JM. Virulence control in group A Streptococcus by a two-component gene regulatory system: global expression profiling and in vivo infection modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13855–13860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202353699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sumby P, Whitney AR, Graviss EA, DeLeo FR, Musser JM. Genome-wide analysis of group A streptococci reveals a mutation that modulates global phenotype and disease specificity. PLoS Pathogens. 2006;2:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klinzing DC, Ishmael N, Hotopp JCD, Tettelin H, Shields KR, Madoff LC, Puopolo KM. The two-component response regulator LiaR regulates cell wall stress responses, pili expression and virulence in group B Streptococcus. Microbiology. 2013;159:1521–1534. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quach D, van Sorge NM, Kristian SA, Bryan JD, Shelver DW, Doran KS. The CiaR response regulator in group B Streptococcus promotes intracellular survival and resistance to innate immune defenses. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2023–2032. doi: 10.1128/JB.01216-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suntharalingam P, Senadheera MD, Mair RW, Lévesque CM, Cvitkovitch DG. The LiaFSR system regulates the cell envelope stress response in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2973–2984. doi: 10.1128/JB.01563-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mascher T, Heintz M, Zähner D, Merai M, Hakenbeck R. The CiaRH system of Streptococcus pneumoniae prevents lysis during stress induced by treatment with cell wall inhibitors and by mutations in pbp2x involved in β-lactam resistance. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1959–1968. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1959-1968.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nizet V, Ohtake T, Lauth X, Trowbridge J, Rudisill J, Dorschner RA, Pestonjamasp V, Piraino J, Huttner K, Gallo RL. Innate antimicrobial peptide protects the skin from invasive bacterial infection. Nature. 2001;414:454–457. doi: 10.1038/35106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li M, Lai Y, Villaruz AE, Cha DJ, Sturdevant DE, Otto M. Gram-positive three-component antimicrobial peptide-sensing system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9469–9474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702159104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pietiäinen M, Gardemeister M, Mecklin M, Leskelä S, Sarvas M, Kontinen VP. Cationic antimicrobial peptides elicit a complex stress response in Bacillus subtilis that involves ECF-type sigma factors and two-component signal transduction systems. Microbiology. 2005;151:1577–1592. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, Gallo RL, Leung DYM. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. New Engl JJ Med. 2002;347:1151–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee PHA, Ohtake T, Zaiou M, Murakami M, Rudisill JA, Lin KH, Gallo RL. Expression of an additional cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide protects against bacterial skin infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3750–3755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500268102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salzman NH, Ghosh D, Huttner KM, Paterson Y, Bevins CL. Protection against enteric salmonellosis in transgenic mice expressing a human intestinal defensin. Nature. 2003;422:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature01520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005;19:1067–1077. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3284com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau Vr, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, Tavera-Mendoza L, Lin R, Hanrahan JH, Mader S, White JH. Cutting Edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3eExpression. The J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Coda AB, Büchau AS, Liu PT, Kiken D, Helfrich YR, Kang S, Elalieh HZ, Steinmeyer A. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:803–811. doi: 10.1172/JCI30142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peyssonnaux C, Datta V, Cramer T, Doedens A, Theodorakis EA, Gallo RL, Hurtado-Ziola N, Nizet V, Johnson RS. HIF-1α expression regulates the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1806–1815. doi: 10.1172/JCI23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peyssonnaux C, Boutin AT, Zinkernagel AS, Datta V, Nizet V, Johnson RS. Critical role of HIF-1α in keratinocyte defense against bacterial infection. J Invest Derm. 2008;128:1964–1968. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Okumura CYM, Hollands A, Tran DN, Olson J, Dahesh S, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, Thienphrapa W, Corle C, Jeung SN, Kotsakis A. A new pharmacological agent (AKB-4924) stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and increases skin innate defenses against bacterial infection. J Mol Med. 2012;90:1079–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dohrmann S, Anik S, Olson J, Anderson EL, Etesami N, No H, Snipper J, Nizet V, Okumura CY. Role for streptococcal collagen-like protein 1 in M1T1 group A Streptococcus resistance to neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4011–4020. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01921-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]