Abstract

Introduction. Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common complaints in the emergency department (ED). There are several research articles providing evidence for acupuncture for treating chronic LBP but few about treating acute LBP. This study assessed the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for the treatment of acute LBP in the ED. Materials and methods. A clinical pilot cohort study was conducted. 60 participants, recruited in the ED, were divided into experimental and control groups with 1 dropout during the study. Life-threatening conditions or severe neurological defects were excluded. The experimental group (n = 45) received a series of fixed points of acupuncture. The control group (n = 14) received sham acupuncture by pasting seed-patches near acupoints. Back pain was measured using the visual analog scale (VAS) at three time points: baseline and immediately after and 3 days after intervention as the primary outcome. The secondary outcomes were heart rate variability (HRV) and adverse events. Results. The VAS demonstrated a significant decrease (P value <0.001) for the experimental group after 15 minutes of acupuncture. The variation in HRV showed no significant difference in either group. No adverse event was reported. Conclusion. Acupuncture might provide immediate effect in reducing the pain of acute LBP safely.

1. Introduction

Most adults have the experience of low back pain (LBP) in their lives [1, 2]. Low back pain is one of the most common complaints when patients visit the emergency department (ED) [3, 4]. Most cases of acute LBP are not related to any specific disease [5–7]. After checking the patients and excluding any life-threatening conditions or severe neurological deficits, sometimes the pain has still not been eased. Patients must be kept in the ED for further observation. The prolonged hospital stay due to poor pain control is a potential factor that can cause the overcrowding of the ED [8].

Pain has been regarded as the fifth vital sign (temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate) recently [9], and every patient has the right to receive adequate pain management. Pain relief is an important work in the ED and there are many medications for LBP with each medication having both benefits and side effects [10–13].

Acupuncture is one of the oldest and most popular complementary alternative medicines in the world and it has been widely utilized for pain, including low back pain, osteoarthritis, headache, and cancer [14–19]. We found that there are many studies assessing the effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic LBP but few for acute LBP [15, 20].

In light of the aforementioned observation, this study focused on evaluating the efficacy and safety of acupuncture in patients with acute LBP through outpatient care in the ED.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

A clinical pilot cohort study was conducted. Patients were recruited from the emergency department (ED) of Changhua Christian Hospital (a medical center in Taiwan) with a target sample size of 60 subjects. Participants were divided into either the experimental group or control group based on their willingness to accept acupuncture treatment. All candidates received a standardized interview process. And the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study were explained thoroughly to the candidates. Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequence. All participants' written consents were obtained. The trial was conducted from March to December, 2014. The clinical trial protocol was approved by the Institute Review Board (IRB) of Changhua Christian Hospital (CCH IRB number 140214).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Participants meeting all of the following criteria will be included:

age 20 to 90 years, either gender;

visit and stay in emergency department;

the chief complaint being acute low back pain;

diagnosis with International Classification of Diseases 9th revision (ICD-9) code 724.2 Lumbago.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Participants meeting one or more of the following criteria were excluded:

serious comorbid conditions (e.g., life-threatening condition or severe neurological defects);

patients who cannot communicate reliably with the investigator or who are not likely to obey the instructions of the trial;

pregnancy status.

2.4. Baseline Assessment

2.4.1. The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)

This questionnaire (also known as Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire) was designed to measure a patient's functional disability resulting from spinal pain [21].

2.5. Interventions

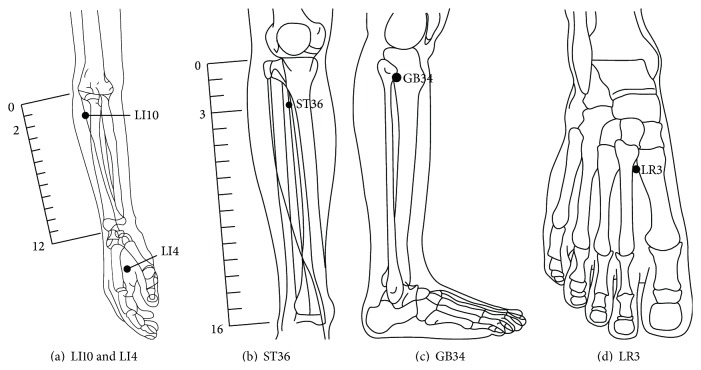

Participants were divided into experimental and control groups based on their willingness to accept acupuncture treatment. The experimental group received a series of fixed points of acupuncture: Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Shousanli (LI10), Zusanli (ST36), Yanlingquan (GB34), and Taichong (LR3) [22]. Needles were correctly inserted and manually stimulated until the “De Qi” sensation was elicited. The needles stayed in place for 15 minutes. The control group received sham acupuncture by pasting seed-patches next to the same location as correct acupoints of experimental group; see Figure 2 [22].

Figure 2.

Acupoint locations (LI4, LI10, ST36, GB34, and LR3).

2.6. Evaluations

The primary outcome evaluation was the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain. It is graded from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) and has proven its usefulness and clinical validity for the evaluation of pain [23]. Patients were evaluated at three timepoints in this study: before intervention (VAS-1), after intervention (VAS-2), 3 days after the intervention (VAS-3).

The secondary outcomes were heart rate variability (HRV) and adverse events. HRV was measured 2 times in this study: before the intervention and after the intervention. Many studies have shown a relation between HRV and pain [24, 25]. We tried to further identify the correlation between the intensity of pain and HRV [26, 27]. An additional secondary outcome was participants reporting any adverse events they experience, including discomfort, bruising at the sites of needle insertion, nausea, or feeling faint during or after treatment.

2.7. Data Analysis

First, the experimental group and control group were analyzed for comparability according to the baseline characteristics, including gender, age, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (systole and diastole), heart rate (HR), and ODI. Chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to assess categorical variables. Second, in order to analyse the outcome of this study including VAS and HRV, we used Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test and Mann-Whitney U test because of the sample size. All tests were conducted using SPSS (V.18.0).

3. Results

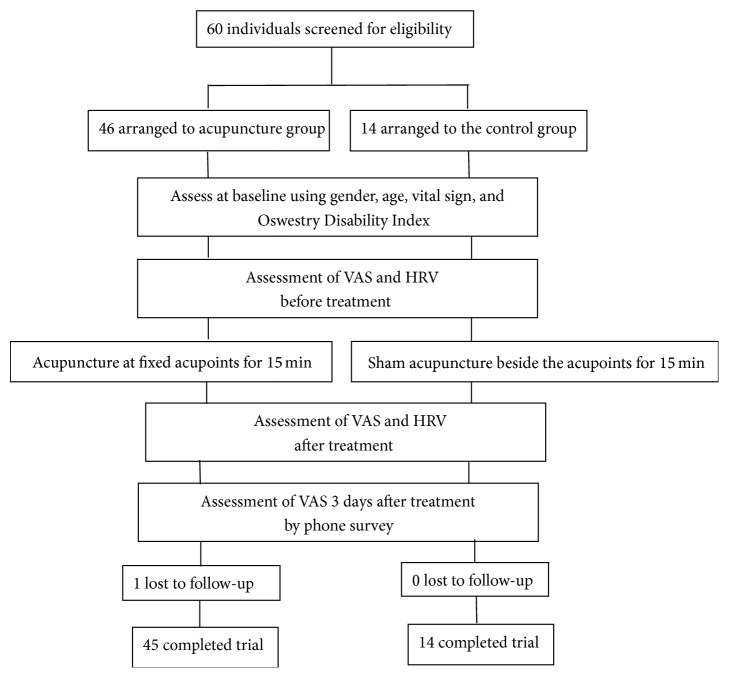

The flowchart of this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Participant Recruitment. All study participants, from the emergency department (ED), were evaluated by emergency medicine specialists to exclude serious comorbid conditions and severe neurological defects, such as infection, cauda equina syndrome, and aneurysm. Sixty participants (21–89 years old, 20 men and 40 women) were recruited into the study and divided into experimental group (n = 46) and control group (n = 14). The VAS was conducted to evaluate the maintenance of the pain relieving effect by phone interview 3 days after treatment. There was 1 participant lost to follow-up in the experimental group at the 3 days after intervention timepoint.

Baseline Characteristics. Tables 1(a) and 1(b) show baseline participant characteristics, including gender, age, BMI, blood pressure, heart rate, and Oswestry Disability Index. The two groups were homogeneous while no significant difference was shown at baseline assessment.

Table 1.

(a) Distribution of participants' gender. (b) Baseline of participant characteristics.

(a).

| Control | Acupuncture | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | 14 | 45 | 0.942 | ||

| Female | 7 | 50.0 | 23 | 51.1 | |

| Male | 7 | 50.0 | 22 | 48.9 | |

P value by Chi-square test.

(b).

| Control (n = 14) | Acupuncture (n = 45) |

P value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| Age | 65 | 52 | 79 | 56 | 46 | 75 | 0.423 |

| BMI | 26 | 23 | 28 | 24 | 22 | 27 | 0.454 |

| SYS | 134 | 119 | 137 | 122 | 117 | 138 | 0.741 |

| DIA | 76 | 73 | 78 | 74 | 71 | 79 | 0.533 |

| HR | 81 | 77 | 91 | 75 | 67 | 88 | 0.303 |

| Oswestry | |||||||

| (1) Pain intensity | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.861 |

| (2) Personal care | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0.930 |

| (3) Lifting | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.024 |

| (4) Walking | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.767 |

| (5) Sitting | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.745 |

| (6) Standing | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.099 |

| (7) Sleeping | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.648 |

| (8) Sex life | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0.448 |

| (9) Social life | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.205 |

| (10) Traveling | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 0.853 |

P value by Mann-Whitney U test.

Q1: Percentile 25.

Q3: Percentile 75.

BMI, body mass index; SYS, systolic pressure; DIA, diastolic pressure; HR, heart rate.

VAS. Comparison of VAS-1 (before intervention) and VAS-2 (after intervention) indicated that there was significant difference in the experimental group (P < 0.001) but not in control group (P = 0.109). Comparison of VAS-1 and VAS-3 (3 days after intervention) found significant differences in both experimental group (P < 0.001) and control group (P = 0.011) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between groups of VAS before, after, and 3 days after intervention.

| Control (n = 14) | Acupuncture (n = 45) | P valueb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | P valuea | Median | Q1 | Q3 | P valuea | ||

| VAS-1 | 5.5 | 4 | 7 | 7.0 | 5 | 8 | 0.059 | ||

| VAS-2 | 4.5 | 4 | 6 | 0.109 | 4.0 | 2 | 5 | <0.001∗ | 0.161 |

| VAS-3 | 3.0 | 0 | 4 | 0.011∗ | 3.0 | 1 | 6 | <0.001∗ | 0.465 |

P valuea by Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test (take VAS1 as reference) (intergroup).

P valueb by Mann-Whitney U test (between groups).

Q1: Percentile 25.

Q3: Percentile 75.

VAS-1, VAS before intervention; VAS-2, VAS after intervention; VAS-3, VAS of 3 days after intervention.

*Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

In addition, comparison of ΔVAS1-VAS2 (changes of VAS-1 and VAS-2) between two groups also showed a significant difference (P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed in ΔVAS1-VAS3 (changes of VAS-1 and VAS-3) (P = 0.370) and ΔVAS2-VAS3 (changes of VAS-2 and VAS-3) (P = 0.181) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in VAS between control group and acupuncture group.

| Control (n = 14) | Acupuncture (n = 45) | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| ΔVAS2-VAS1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | −2.0 | −4 | −1 | <0.001∗ |

| ΔVAS3-VAS1 | −1.5 | −3 | 0 | −4.0 | −5 | −1 | 0.370 |

| ΔVAS3-VAS2 | −1.5 | −3 | 0 | −1.0 | −3 | 2 | 0.181 |

P value by Mann-Whitney U test.

Q1: Percentile 25.

Q3: Percentile 75.

*Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

ΔVAS2-VAS1, changes of VAS-2 and VAS-1; ΔVAS3-VAS1, changes of VAS-3 and VAS-1; ΔVAS3-VAS2, changes of VAS-3 and VAS-2.

Furthermore, when we do the gamma regression model with GEE method on VAS, the results also indicate a significant change after treatment in the experimental group (P < 0.001) but not in the control group. The VAS reduced significantly in all patients after 3 days (P = 0.031) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of gamma regression model with GEE method on VAS.

| Predictor | Coefficient | SE | Mean ratio | 95% C.I. | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.701 | 0.368 | 5.478 | 2.665–11.259 | <0.001∗ |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.002 | 1.001 | 0.997–1.005 | 0.637 |

| BMI | −0.001 | 0.012 | 0.999 | 0.977–1.022 | 0.920 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 0.008 | 0.096 | 1.008 | 0.835–1.215 | 0.936 |

| Female | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Group | |||||

| Acupuncture | 0.156 | 0.098 | 1.169 | 0.964–1.417 | 0.113 |

| Control | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Time | |||||

| 3 | −0.377 | 0.175 | 0.686 | 0.487–0.966 | 0.031∗ |

| 2 | −0.132 | 0.077 | 0.876 | 0.753–1.019 | 0.086 |

| 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Interaction | |||||

| Acupuncture Time 3 | 0.021 | 0.196 | 1.021 | 0.695–1.499 | 0.916 |

| Acupuncture Time 2 | −0.380 | 0.092 | 0.684 | 0.571–0.819 | <0.001∗ |

| Acupuncture Time 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Control Time 3 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Control Time 2 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Control Time 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

*Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

HRV. Table 4 shows the comparison of all parameters of HRV before and after intervention in experimental group and control group. No significant change was observed in HRV, HF%, LF%, LF/HF, VLF, LF RMSSD, and PNN50 in both groups in this study.

Table 4.

Comparison of parameters of heart rate variability (HRV) before and after intervention in two groups.

| Group | Before | After | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Q1 | Q3 | |||

| Control (n = 14) |

HRV | 39.0 | 33.0 | 49.0 | 31.0 | 26.0 | 45.0 | 0.311 |

| HF% | 50.0 | 38.0 | 58.0 | 53.0 | 48.0 | 76.0 | 0.421 | |

| LF% | 50.0 | 42.0 | 62.0 | 47.0 | 24.0 | 52.0 | 0.421 | |

| LF/HF | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.133 | |

| VLF | 976.0 | 567.0 | 1436.0 | 628.0 | 501.0 | 1098.0 | 0.463 | |

| Number of irreg. hb. | 8.0 | 0.0 | 48.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 0.229 | |

| LF | 305.0 | 92.0 | 509.0 | 154.0 | 54.0 | 199.0 | 0.552 | |

| HF | 258.0 | 196.0 | 323.0 | 224.0 | 133.0 | 428.0 | 0.916 | |

| Total power | 1521.0 | 1089.0 | 2401.0 | 961.0 | 676.0 | 2025.0 | 0.311 | |

| Variance | 1521.0 | 1089.0 | 2401.0 | 961.0 | 676.0 | 2025.0 | 0.311 | |

| RMSSD | 45.0 | 29.0 | 52.0 | 41.0 | 22.0 | 54.0 | 0.674 | |

| PNN50 | 13.0 | 8.0 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 1.0 | 30.0 | 0.753 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Acupuncture (n = 45) |

HRV | 40.0 | 25.0 | 83.0 | 34.0 | 24.0 | 58.0 | 0.273 |

| HF% | 45.0 | 32.0 | 61.0 | 46.0 | 32.0 | 60.0 | 0.694 | |

| LF% | 55.0 | 39.0 | 68.0 | 53.0 | 39.0 | 68.0 | 0.905 | |

| LF/HF | 1.2 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.923 | |

| VLF | 891.0 | 382.0 | 4272.0 | 732.0 | 423.0 | 2274.0 | 0.561 | |

| Number of irreg. hb. | 11.0 | 0.0 | 49.0 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 22.0 | 0.158 | |

| LF | 204.0 | 77.0 | 1095.0 | 185.0 | 53.0 | 667.0 | 0.891 | |

| HF | 208.0 | 68.0 | 932.0 | 141.5 | 71.0 | 503.0 | 0.446 | |

| Total power | 1600.0 | 625.0 | 6889.0 | 1157.0 | 576.0 | 3364.0 | 0.401 | |

| Variance | 1600.0 | 625.0 | 6889.0 | 1157.0 | 576.0 | 3364.0 | 0.401 | |

| RMSSD | 34.0 | 22.0 | 75.0 | 32.0 | 22.0 | 59.0 | 0.573 | |

| PNN50 | 11.0 | 1.0 | 45.0 | 8.5 | 2.0 | 31.0 | 0.353 | |

P value by Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test.

Q1: Percentile 25.

Q3: Percentile 75.

HF, high frequency; LF, low frequency; VLF, very low frequency; Number of irreg. hb., number of irregular heart beats; RMSSD, root mean square successive difference; PNN50, NN50 count divided by the total number of all NN intervals.

Adverse Events. No side effects were reported in this study. No patients reported bleeding, nausea, vomiting, feeling faint, or any other complication during or after intervention.

4. Discussion

This study was designed to demonstrate that acupuncture can benefit patients with acute LBP. Instead of recruiting participants from acupuncture outpatients, we cooperated with emergency medicine specialists in order to make the first contact with patients with acute LBP. Clinically we found that most patients with acute LBP would not be able to maintain the face-down posture during the treatment time. Therefore, all the acupoints we chose in this study were at the limbs and based on traditional Chinese medical meridian system, so patients could keep a relatively comfortable lying down position.

In the results of this study, the significant difference between VAS-1 and VAS-2 in the experimental group might prove the efficacy of acupuncture while no statistical variation was shown in control group. Another significant variation was shown in the change of VAS-1 and VAS-2 (ΔVAS1-VAS2) between two groups. It also indicated that acupuncture intervention might reduce the pain intensity. The other significant variation was between VAS-1 and VAS-3 in both groups. And it was considered as acute LBP could be mitigated through appropriate treatment without immediate recurrence [28].

HRV measures the balance of autonomic nervous system which reflects physiological, hormonal, and emotional balance within our body [29]. Many studies have proved that there are statistical differences of HRV between healthy people and patients in pain [24, 30]. But the correlation between HRV and pain intensity has not been clearly demonstrated [24, 31]. In our study, no significant difference was shown in both experimental and control group after intervention. We assume that patients might feel much less pain after 15 minutes of acupuncture (mean 6.64 ± 1.87 to 3.98 ± 1.74) but have not yet fully recovered to pain-free state.

We used the adverse event record to assess the safety. No complication was reported showing that acupuncture could be a safe treatment in patients with acute LBP. However, our study has several limitations. One limitation concerned the different number of participants between two groups. Acupuncture is a common and popular medical service in the Chinese society. Patients are usually willing to accept it. It resulted in the fact that less participants were recruited into control group when our strategy was to divide participants into two groups based on their willingness to accept acupuncture.

Another limitation was that this study was not designed as randomized blind. Considering that acupuncture is well-known in the Chinese society, it is difficult to do blinded study about acupuncture. In order to minimize the bias from this, we used seed-patches as sham acupuncture. Seed-patches are often used in auricular acupuncture. Auricular acupuncture is another well-known Chinese medical service. We tried to convince participants in control group that they were also receiving another effective treatment by pasting the seed-patches near the correct acupoints [32, 33]. Still, biases introduced by this unblinded approach cannot be ruled out.

A larger sample size in future studies is indispensable to provide well-defined types of acute low back pain for our evidence-based practice.

5. Conclusion

We conclude that acupuncture could provide immediate effect in reducing pain of acute low back pain significantly. The results from this study provide clinical evidence on the efficacy and safety of acupuncture to treat acute low back pain in the emergency department. Nevertheless, further larger studies are needed to replicate the findings of this study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (Program no. MOHW-103-CMC-2). The authors would like to thank all of the participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

Yen-Ting Liu collected the data, did the literature search, and drafted the paper. Yen-Ting Liu, Chih-Wen Chiu, Chin-Fu Chang, Tsung-Chieh Lee, Chia-Yun Chen, Shun-Chang Chang, Chia-Ying Lee, and Lun-Chien Lo participated in the conception and design of the study. Tsung-Chieh Lee, Chia-Yun Chen, Shun-Chang Chang, and Chia-Ying Lee conducted acupuncture treatment and seed-patches. Lun-Chien Lo did the critical revision of the paper and was the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Deyo R. A., Weinstein J. N. Low back pain. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(5):363–370. doi: 10.1056/nejm200102013440508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson G. B. J. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. The Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581–585. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deyo R. A., Mirza S. K., Martin B. I. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31(23):2724–2727. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borczuk P. An evidence-based approach to the evaluation and treatment of low back pain in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Practice. 2013;15(7):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Della-Giustina D., Kilcline B. A. Acute low back pain: a comprehensive review. Comprehensive Therapy. 2000;26(3):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s12019-000-0002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa T. M., Baptista A. S., de Souza M. C., Yoshizumi A. M., Natour J. Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, placebo trial. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2014;32:109–115. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2013-010333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Tulder M. W., Assendelft W. J. J., Koes B. W., Bouter L. M. Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of observational studies. Spine. 1997;22(4):427–434. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fromm R. E., Jr., Gibbs L. R., McCallum W. G. B., et al. Critical care in the emergency department: a time-based study. Critical Care Medicine. 1993;21(7):970–976. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasero C. L., McCaffery M. Pain: Clinical Manual. Mosby Incorporated; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Tulder M. W., Koes B. W., Bouter L. M. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997;22(18):2128–2156. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199709150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogt M. T., Kwoh C. K., Cope D. K., Osial T. A., Culyba M., Starz T. W. Analgesic usage for low back pain: impact on health care costs and service use. Spine. 2005;30(9):1075–1081. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000160843.77091.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherkin D. C., Wheeler K. J., Barlow W., Deyo R. A. Medication use for low back pain in primary care. Spine. 1998;23(5):607–614. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behrbalk E., Halpern P., Boszczyk B. M., et al. Anxiolytic medication as an adjunct to morphine analgesia for acute low back pain management in the emergency department: a prospective randomized trial. Spine. 2014;39(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molsberger A. F., Zhou J., Boewing L., et al. An international expert survey on acupuncture in randomized controlled trials for low back pain and a validation of the low back pain acupuncture score. European Journal of Medical Research. 2011;16(3):133–138. doi: 10.1186/2047-783x-16-3-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg D. M., Post D. E., Davis R. B., et al. Addition of choice of complementary therapies to usual care for acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32(2):151–158. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000252697.07214.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manheimer E., Cheng K., Linde K., et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001977.pub2.CD001977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linde K., Allais G., Brinkhaus B., Manheimer E., Vickers A., White A. R. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007587.CD007587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams M., Jewell A. P. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients. International Seminars in Surgical Oncology. 2007;4, article 10 doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlan A. D., van Tulder M. W., Cherkin D. C., et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2.CD001351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairbank J. C. T., Pynsent P. B. The oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000;25(22):2940–2953. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations in the Western Pacific Region. WHO Western Pacific Region; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bijur P. E., Silver W., Gallagher E. J. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001;8(12):1153–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sesay M., Robin G., Tauzin-Fin P., et al. Responses of heart rate variability to acute pain after minor spinal surgery: optimal thresholds and correlation with the numeric rating scale. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000102. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appelhans B. M., Luecken L. J. Heart rate variability and pain: associations of two interrelated homeostatic processes. Biological Psychology. 2008;77(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boselli E., Daniela-Ionescu M., Bégou G., et al. Prospective observational study of the non-invasive assessment of immediate postoperative pain using the analgesia/nociception index (ANI) British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2013;111(3):453–459. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J., Dean D., Nosco D., Strathopulos D., Floros M. Effect of chiropractic care on heart rate variability and pain in a multisite clinical study. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2006;29(4):267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coste J., Delecoeuillerie G., Cohen De Lara A., Le Parc J. M., Paolaggi J. B. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: an inception cohort study in primary care practice. British Medical Journal. 1994;308(6928):577–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6928.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung J. W. Y., Yan V. C. M., Zhang H. Effect of acupuncture on heart rate variability: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014;2014:19. doi: 10.1155/2014/819871.819871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Södervall J., Karppinen J., Puolitaival J., et al. Heart rate variability in sciatica patients referred to spine surgery: a case control study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14, article 149 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meeuse J. J., Löwik M. S. P., Löwik S. A. M., et al. Heart rate variability parameters do not correlate with pain intensity in healthy volunteers. Pain Medicine. 2013;14(8):1192–1201. doi: 10.1111/pme.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C. S., Yang A. W., Zhang A. L., May B. H., Xue C. C. Sham control methods used in ear-acupuncture/ear-acupressure randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2014;20(3):147–161. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Que Q., Ye X., Su Q., et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture intervention for neck pain caused by cervical spondylosis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1, article 186) doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]