Abstract

AIM: To investigate the postoperative transfusion and complication rates of anemic and nonanemic total joint arthroplasty patients given tranexamic acid (TXA).

METHODS: A cross-sectional prospective study was conducted of primary hip and knee arthroplasty cases performed from 11/2012 to 6/2014. Exclusion criteria included revision arthroplasty, bilateral arthroplasty, acute arthroplasty after fracture, and contraindication to TXA. Patients were screened prior to surgery, with anemia was defined as hemoglobin of less than 12 g/dL for females and of less than 13 g/dL for males. Patients were divided into four different groups, based on the type of arthroplasty (total hip or total knee) and hemoglobin status (anemic or nonanemic). Intraoperatively, all patients received 2 g of intravenous TXA during surgery. Postoperatively, allogeneic blood transfusion (ABT) was directed by both clinical symptoms and relative hemoglobin change. Complications were recorded within the first two weeks after surgery and included thromboembolism, infection, and wound breakdown. The differences in transfusion and complication rates, as well as the relative hemoglobin change, were compared between anemic and nonanemic groups.

RESULTS: A total of 232 patients undergoing primary joint arthroplasty were included in the study. For the total hip arthroplasty cohort, 21% (18/84) of patients presented with preoperative anemia. Two patients in the anemic group and two patients in the nonanemic group needed ABTs; this was not significantly different (P = 0.20). One patient in the anemic group presented with a deep venous thromboembolism while no patients in the nonanemic group had an acute complication; this was not significantly different (P = 0.21). For nonanemic patients, the average change in hemoglobin was 2.73 ± 1.17 g/dL. For anemic patients, the average change in hemoglobin was 2.28 ± 0.96 g/dL. Between the two groups, the hemoglobin difference of 0.45 g/dL was not significant (P = 0.13). For the total knee arthroplasty cohort, 18% (26/148) of patients presented with preoperative anemia. No patients in either group required a blood transfusion or had an acute postoperative complication. For nonanemic patients, the average change in hemoglobin was 1.85 ± 0.79 g/dL. For anemic patients, the average change in hemoglobin was 1.09 ± 0.58 g/dL. Between the two groups, the hemoglobin difference of 0.76 g/dL was significant (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: TXA administration results in low transfusion and complication rates and may be a useful adjunct for TJA patients with preoperative anemia.

Keywords: Total knee replacement, Tranexamic acid, Total hip replacement, Preoperative anemia

Core tip: Patients with preoperative anemia presenting for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) have an increased risk of requiring allogeneic blood transfusion (ABT). Current methods to increase preoperative hemoglobin is expensive, limited in efficacy, and have side effects. In this study, we found that intraoperative tranexamic acid (TXA) safely and effectively decreases blood loss and limits the rate of ABT after TJA for anemic patients. We recommend TXA for all patients without contraindications who have preoperative anemia.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 20% of patients presenting for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) have preoperative anemia and are at a relatively higher risk of needing allogeneic blood transfusion (ABT)[1-6]. This rate reflects the overall prevalence of anemia in the general elderly population, defined by the World Health Organization as hemoglobin (Hb) < 12 g/dL in females and < 13 g/dL in males, and can be contributed to by causes such as nutritional deficiency or chronic disease[7,8]. Preoperative and perioperative blood management is of considerable importance for these patients, especially given the influence of postoperative anemia on functional recovery, complications, and outcome[1,2]. Although there have been no large studies examining the effect of preoperative anemia on mortality after TJA, studies in the hip fracture[9,10], cardiac[11], vascular[12], and general surgery[13] patient populations have shown an increase in mortality rates. It is likely that there may be a similar effect with TJA.

Multiple authors have proposed preoperative screening and treatment protocols to limit the potential for perioperative anemia[14-17]. General factors such as patient weight, comorbidities, and nutritional deficiencies should be addressed to optimize hematologic status[18]. Preoperative Hb should be routinely obtained and a thorough analysis performed for moderate to severe levels of anemia to determine the etiology of the disorder[18]. A preoperative Hb of 13 g/dL has historically been held as the gold standard to minimize the rate of symptomatic perioperative anemia[1].

Tranexamic acid (TXA) has gained popularity as an intraoperative adjunct to help decrease blood loss and perioperative anemia. TXA is a lysine analog that competitively inhibits the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, slowing the rate of fibrinolysis[19]. It can be applied intravenously or topically[20] has a short half-life, and preferentially affects fibrinolysis in the surgical field[21]. Although there have been sporadic case reports about side-effects, there have been no large-scale studies that show a significant increase in complications such as symptomatic thromboembolism[22-25]. When compared to other treatments, most specifically erythropoietin, TXA can be cost-effective[26]. The analog has been well documented as efficacious in orthognathic[27], cardiac[28], and spine[29] procedures. Multiple studies have shown a decrease in blood loss and ABT with TXA application for both primary and revision TJA[22-25,30,31]. The effect of TXA on patients presenting with preoperative anemia has been less well examined.

The purpose of this study was to compare rates of transfusion and postoperative complications between anemic and nonanemic patients given TXA who underwent primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Our hypothesis was that there would be no significant difference in the rates of transfusion and complications for both groups of patients. If supported, this could lead to changes in preoperative management for anemic TJA patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective cross-sectional study was performed from 11/2012 to 6/2014 at a tertiary university academic institution. Patients undergoing elective primary THA or TKA by the lead author were eligible. Exclusion criteria included revision or bilateral TJA, TJA after hip fracture, or patients with contraindications towards receiving TXA.

Preoperative

Preoperative Hb was measured within 3 wk prior to surgery and patients were classified as anemic vs nonanemic based on World Health Organization guidelines (< 12 g/dL in females and < 13 g/dL in males). Patients were not prescribed supplemental treatment, such as iron supplementation or erythropoietin, and were advised to stop blood-thinning medications such aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications 1 wk prior to surgery.

Intraoperative

All patients received two doses of intravenous TXA in the perioperative period: 1 g prior to incision and 1 g during wound closure. Spinal anesthesia was used for all eligible patients as determined by the anesthesia team; patients deemed ineligible received a general anesthetic with endotracheal tube. TKA patients were placed in the supine position, had a tourniquet applied prior to incision, and a standard parapatellar approach utilized to implant a cemented metal-on-polyetheylene system. THA patients were placed in the lateral decubitus position with a standard posterior approach utilized to implant a non-cemented metal or ceramic-on-polyethylene system. Fluid resuscitation and transfusion requirement was managed by the anesthesia team following standard guidelines. A cocktail for pain control, including 80 mcg clonidine, 30 mg ketorolac, 0.5 mL 1:1000 epinepherine, and 49.25 mL 0.5% ropivicaine, combined with normal saline to a total volume of 100 mL, was injected into the joint capsule and surrounding tissues prior to final closure in both groups.

Postoperative

Patients were admitted to the Orthopaedics unit and followed a standardized postoperative protocol, including aggressive multimodal pain control with oral medications and physical therapy starting on the day of surgery. Coumadin and a sequential compression device were used to prevent thrombus formation. Hb was measured for all patients on the first postoperative day, as well as for the majority of patients on subsequent days as required. Transfusion was dictated by a significant decrease in Hb combined with clinical symptoms or changes in physiologic parameters. An absolute Hb threshold for transfusion was not used. Discharge was typically on the third postoperative day. Any postoperative complications up to the first postoperative visit, typically at two weeks, were recorded. Complications included superficial hematoma formation, deep joint effusion, wound breakdown, thromboembolism, and acute infection.

Statistical analysis

Patients were divided into one of four groups based on preoperative Hb and type of arthroplasty performed (nonanemic vs anemic, TKA vs THA). In each surgical group (TKA and THA), the nonanemic patients were used as controls and the anemic patients as the study groups. A two-sample T test was used to compare the average change in Hb between each of the groups (e.g., anemic TKA vs nonanemic TKA). A Fisher exact test was used to compare the rate of complications between each of the groups as well as the rate of transfusion between each of the groups. Significance was set at the P value of ≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Richmond WA).

RESULTS

A total of 232 patients met inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and outcome

| Anemic THA | Nonanemic THA | Anemic TKA | Nonanemic TKA | |

| Number | 18 | 66 | 26 | 122 |

| Gender (M/F) | 10/8 | 33/33 | 10/16 | 48/74 |

| Age | 63.0 (± 15.6) | 60.0 (± 13.8) | 68.2 (± 8.6) | 67.0 (± 10.2) |

| Preoperative Hb (g/dL) | 11.45 (± 0.82) | 13.85 (± 0.92) | 11.43 (± 0.72) | 13.66 (± 0.94) |

| Hospital day 1 Hb (g/dL) | 9.17 (± 1.26) | 11.11 (± 1.35) | 10.34 (± 0.91) | 11.81 (± 1.09) |

| Hb change (g/dL) | 2.28 (± 0.96) | 2.73 (± 1.17) | 1.09 (± 0.58)1 | 1.85 (± 0.79)1 |

| Transfusions | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Complications | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Significant difference in hemoglobin change between anemic TKA and nonanemic TKA patients (P < 0.001). THA: Total hip arthroplasty; TKA: Total knee arthroplasty; Hb: Hemoglobin.

THA

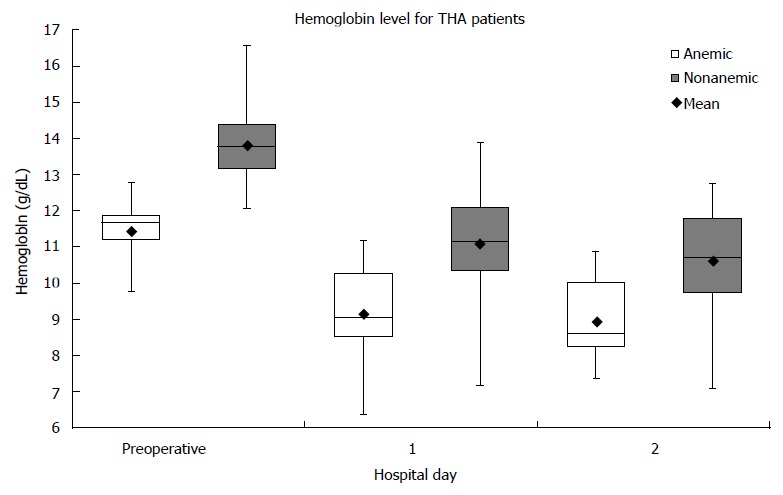

Eighty-four patients had THA performed. Twenty-one percent (18/84) of the patients presented with preoperative anemia. For nonanemic patients, the average change in Hb from preoperative to the first postoperative day was 2.73 ± 1.17 g/dL. For anemic patients, the average change in Hb from preoperative to the first postoperative day was 2.28 ± 0.96 g/dL (Figure 1). Between the two groups, the Hb difference of 0.45 g/dL was not significant (P = 0.13). Two patients in the nonanemic group and two patients in the anemic group required ABT. There was no significant difference in the rate of ABT (P = 0.20). One patient in the anemic group presented with a deep venous thrombosis at the fourth postoperative day; there were no complications for patients in the nonanemic group. There was no significant difference in the rate of all immediate postoperative complications (P = 0.21).

Figure 1.

Hemoglobin levels in total hip arthroplasty using tranexamic acid. Boxplots showing median and interquartile ranges for hemoglobin levels in each group on each hospital day are shown. Both groups experienced a fall in hemoglobin following surgery and both groups had at least one patient who required transfusion on the first postoperative day. Despite the differences in starting hemoglobin, there was no significant difference between groups in rate of transfusion. THA: Total hip arthroplasty.

TKA

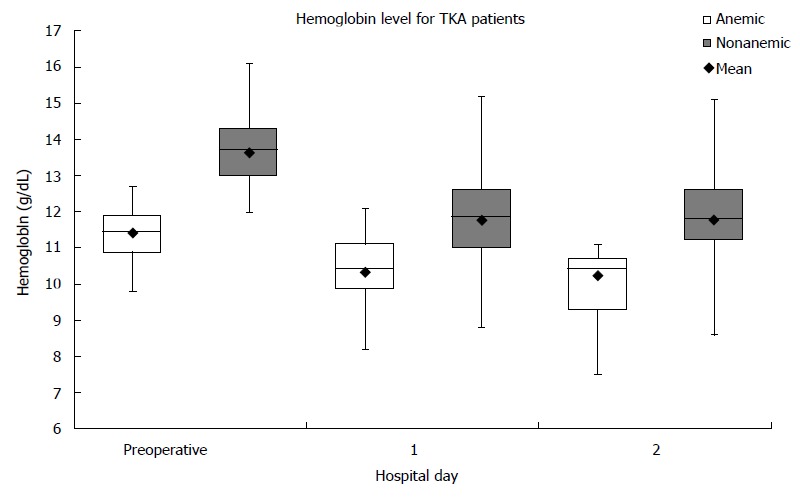

One hundred and forty-eight patients had TKA performed. Eighteen percent (26/148) of the patients presented with preoperative anemia. For nonanemic patients, the average change in Hb from preoperative to the first postoperative day was 1.85 ± 0.79 g/dL. For anemic patients, the average change in Hb from preoperative to the first postoperative day was 1.09 ± 0.58 g/dL (Figure 2). Between the two groups, the Hb difference of 0.76 g/dL was significant (P < 0.001). No patients in either group required ABT. No patients in either group presented with complications within the first post-operative visit.

Figure 2.

Hemoglobin levels in total knee arthroplasty using tranexamic acid. Boxplots showing median and interquartile ranges for hemoglobin levels in each group on each hospital day are shown. Both groups experienced a fall in hemoglobin following; in this case the nonanemic patients had a significant greater fall then the anemic patients at the first postoperative day (but still had a higher median hemoglobin). None of the patients in either group required transfusion. TKA: Total knee arthroplasty.

DISCUSSION

Current methods to increase Hb in patients with preoperative anemia have disadvantages. The results of iron supplementation are inconclusive, with studies showing diverging effects on preoperative Hb[6,32-34]. Common side effects such as constipation, and abdominal pain can lower the adherence rate[32]. Recombinant human erythropoietin has been shown to be efficacious[35-37], but is only available via an intravenous or subcutaneous route and is relatively expensive[14,38]. Preoperative autologous donation provides the patient a safe supply of blood[39] but physiologic compensation after donation may be inadequate[40] and a significant amount of donated blood is unused[1,40,41]. As such, the goal of this study was to determine if TXA would be useful as an alternative strategy for patients with preoperative anemia to limit the rate of blood loss and ABT.

As expected from undergoing a TJA, all patients had a decrease in Hb at the first postoperative day. Anemic and nonanemic patients who underwent THA had a similar decrease in Hb, with anemic patients averaging only an additional 0.45 g/dL of blood loss. This supported the hypothesis that TXA would result in equivalent rates of blood loss, regardless of preoperative Hb levels. However, nonanemic patients who underwent TKA averaged a decrease in Hb that was significantly greater than that for anemic patients, at 0.76 g/dL; this was unexpected. It is not entirely clear what caused this difference in Hb change, but it may simply be that nonanemic patients lose more red cells per ml of blood lost than anemic patients (due to intraoperative fluid resuscitation), so for equivalent volumes lost between groups the nonanemic group would be expected to have lost more red cell mass overall and therefore experience a bigger drop in Hb. As all patients received fluids during the perioperative period according to strict guidelines following anesthesia protocol based on patient weight and hemodynamic status, it is unlikely that differences in fluid administration were contributive. Finally, only one patient, in the anemic THA group, had a postoperative complication, well within the normal occurrence rate reported for THA[42]. The thrombosis was treated with anticoagulation and did not result in symptomatic embolism. This low rate of complications reaffirms the safe use of TXA as seen in the current literature.

There was no significant difference in the rate of ABT for anemic and nonanemic patients treated with TXA during THA, and none of the TKA patients required transfusion. This supports the hypothesis that use of TXA would result in equivalent rates of perioperative transfusion, regardless of preoperative blood levels. Given that patients with preoperative anemia generally require a higher rate of transfusion, the results suggest that TXA may actually decrease the rate of ABT for this patient population. The potential significance of this finding is two-fold. First, patients with a mild level of anemia may not require any preoperative or perioperative adjunct treatment aside from TXA, such as PO or IV iron supplementation or erythropoietin. Limiting the use of these treatments may decrease concerns about patient compliance and reduce overall surgical costs, as well as rare but real complications from the therapies themselves. In addition, the threshold to operate on patients may be lowered, increasing the availability of TJA for patients with anemia. For these patients, a preoperative course combining multiple treatment modalities in addition to perioperative TXA may be sufficient to minimize significant blood loss and ABT requirements.

This study has several limitations. All procedures were performed by a single surgeon and thus operative blood loss may not be equivalent to that of other surgeons using alternative TJA techniques. Because the study highlighted the relative change (as opposed to absolute values) in Hb, the overall impact of this limitation should be small. In addition, the same approach and same implant system was used by the surgeon for the procedures, which limited variation in surgical technique. The study population was not large, which resulted in a low number of patients with anemia, and thus power could have been increased by enrolling additional patients. However, the percentage of patients presenting with preoperative anemia was equivalent to the rates seen in the existing literature, suggesting that the study population was a suitable representation of the patient population. As such, a formal power analysis was not performed. Another limitation was with regard to the rates of transfusion; with only four ABT’s in the study it is possible that a much larger sample may have demonstrated differences, though even here the conclusion that TXA may allow safe TJA at lower Hb levels would not have changed. Finally, the decision for ABT was not dictated by a single factor, such as postoperative Hb. The current literature is increasingly supportive of using a restrictive transfusion threshold similar to that used in this study, but it is possible that other centers with more liberal transfusion practices may have different results.

In this study, there was no significant difference in the rate of autologous blood transfusion and postoperative complications for anemic and nonanemic patients presenting for lower-extremity TJA when TXA was used. These results support the use of TXA as a safe and effective agent to limit perioperative blood transfusion in patients with preoperative anemia. Potentially, TXA may be used as the single treatment for patients with mild anemia, in place of preoperative methods such as iron supplementation and erythropoietin. TXA may also be helpful when combined with these adjuncts for patients with more severe anemia. Further investigations concerning TXA in patients with preoperative anemia are recommended. Topics to be considered, or are currently under examination, include comparing efficacy and analyzing cost-benefit of TXA vs different preoperative treatments (e.g., iron supplementation, erythropoietin). These studies will ideally lead to a standardized and cohesive protocol for TJA patients with preoperative anemia.

COMMENTS

Background

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) of the hip and knee are successful surgeries that can dramatically reduce pain and increase function for patients with end-stage joint arthritis. However, despite changes in surgical approaches, techniques, and implants, intraoperative blood loss requiring blood transfusion is still prevalent, especially for patients presenting with anemia. Currently, the therapeutic options to treat preoperative anemia are limited and not commonly used.

Research frontiers

Tranexamic acid (TXA) has been highlighted in the last half-decade as a way to decrease intraoperative blood loss. Application during surgery, via intravenous or topical, has been shown to decrease the rate of blood transfusion in THA patients. TXA use has also expanded to other fields of orthopaedics, such as spine surgery.

Innovations and breakthroughs

To the authors’ knowledge, no previous study has closely examined TXA use on THA patients presenting with preoperative anemia. The current study is the first to directly compare blood loss, transfusion rate, and complication rate for anemic THA patients given TXA vs nonanemic controls. With the results shown, it may be possible to use TXA as the sole treatment for patients with mild anemia and as a adjunct with other treatment options for patients with severe anemia.

Applications

The current study shows the efficacy and safety of TXA use for THA patients presenting with preoperative anemia and suggests that routine use in anemic patients with no contraindications is warranted to limit the rate of blood transfusion.

Terminology

TXA - synthetic lysine analog that competitively inhibits the activation of plasminogen to plasmin. Anemia - Defined by the World Health Organization as hemoglobin < 12 g/dL in adult females and < 13 g/dL in adult males.

Peer-review

This is a manuscript which compares rates of transfusion and postoperative complications between anemic and nonanemic patients given TXA who underwent primary total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. This is an interesting paper on a relevant issue. The paper is well written and well structured.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the UCI Institutional Review Board.

Clinical trial registration statement: Because all study participants received the same treatment, the project was not registered as a clinical trial.

Informed consent statement: All study participants provided written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Dr. Duy Phan has no relevant disclosures to make in relation to the submitted study. Dr. Phan has not received research funding, speaker fees, consulting fees, or royalties from any organizations. Dr. Phan is an employee of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, Irvine. Dr. Phan does not own company stock or options. Dr. Phan does not own any patents. Dr. Phan is not on the editorial board of any journals. Dr. Phan is a not a board member of any societies.

Data sharing statement: All technical data is available from the corresponding author at phandl@uci.edu. Consent was not obtained, but the presented data is anonymized and the risk of identification is low.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 7, 2015

First decision: February 7, 2015

Article in press: June 16, 2015

P- Reviewer: Bicanic G, Franklyn MJ, Labek G S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

References

- 1.Bierbaum BE, Callaghan JJ, Galante JO, Rubash HE, Tooms RE, Welch RB. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:2–10. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:482–495. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e08e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salido JA, Marín LA, Gómez LA, Zorrilla P, Martínez C. Preoperative hemoglobin levels and the need for transfusion after prosthetic hip and knee surgery: analysis of predictive factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:216–220. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saleh E, McClelland DB, Hay A, Semple D, Walsh TS. Prevalence of anaemia before major joint arthroplasty and the potential impact of preoperative investigation and correction on perioperative blood transfusions. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:801–808. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerin S, Collins C, Kapoor H, McClean I, Collins D. Blood transfusion requirement prediction in patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Transfus Med. 2007;17:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2006.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers E, O’Grady P, Dolan AM. The influence of preclinical anaemia on outcome following total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:699–701. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:444–454. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bross MH, Soch K, Smith-Knuppel T. Anemia in older persons. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:480–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young G, Drife J. Home or hospital birth? Practitioner. 1992;236:672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruson KI, Aharonoff GB, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. The relationship between admission hemoglobin level and outcome after hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:39–44. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Beattie WS. Risk associated with preoperative anemia in cardiac surgery: a multicenter cohort study. Circulation. 2008;117:478–484. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.718353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta PK, Sundaram A, Mactaggart JN, Johanning JM, Gupta H, Fang X, Forse RA, Balters M, Longo GM, Sugimoto JT, et al. Preoperative anemia is an independent predictor of postoperative mortality and adverse cardiac events in elderly patients undergoing elective vascular operations. Ann Surg. 2013;258:1096–1102. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288e957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, Spahn DR, Rosendaal FR, Habbal A, Khreiss M, Dahdaleh FS, Khavandi K, Sfeir PM, et al. Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1396–1407. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez V, Monsaingeon-Lion A, Cherif K, Judet T, Chauvin M, Fletcher D. Transfusion strategy for primary knee and hip arthroplasty: impact of an algorithm to lower transfusion rates and hospital costs. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:794–800. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Porras JR, Colado E, Conde MP, Lopez T, Nieto MJ, Corral M. An individualized pre-operative blood saving protocol can increase pre-operative haemoglobin levels and reduce the need for transfusion in elective total hip or knee arthroplasty. Transfus Med. 2009;19:35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierson JL, Hannon TJ, Earles DR. A blood-conservation algorithm to reduce blood transfusions after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1512–1518. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashiq S, Jamieson-Lega K, Komarinski C, Nahirniak S, Zinyk L, Finegan B. Allogeneic blood transfusion reduction by risk-based protocol in total joint arthroplasty. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine BR, Haughom B, Strong B, Hellman M, Frank RM. Blood management strategies for total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:361–371. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-06-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormack PL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the treatment of hyperfibrinolysis. Drugs. 2012;72:585–617. doi: 10.2165/11209070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel JN, Spanyer JM, Smith LS, Huang J, Yakkanti MR, Malkani AL. Comparison of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1528–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benoni G, Lethagen S, Fredin H. The effect of tranexamic acid on local and plasma fibrinolysis during total knee arthroplasty. Thromb Res. 1997;85:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31:529–537. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0303100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:39–46. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:1577–1585. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B12.26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandhi R, Evans HM, Mahomed SR, Mahomed NN. Tranexamic acid and the reduction of blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:184. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillette BP, Maradit Kremers H, Duncan CM, Smith HM, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW, Sierra RJ. Economic impact of tranexamic acid in healthy patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sankar D, Krishnan R, Veerabahu M, Vikraman B. Evaluation of the efficacy of tranexamic acid on blood loss in orthognathic surgery. A prospective, randomized clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greiff G, Stenseth R, Wahba A, Videm V, Lydersen S, Irgens W, Bjella L, Pleym H. Tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusions in elderly patients undergoing combined aortic valve and coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26:232–238. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang B, Li H, Wang D, He X, Zhang C, Yang P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative intravenous tranexamic acid use in spinal surgery. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wind TC, Barfield WR, Moskal JT. The effect of tranexamic acid on transfusion rate in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:387–389. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wind TC, Barfield WR, Moskal JT. The effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss and transfusion rate in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1080–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lachance K, Savoie M, Bernard M, Rochon S, Fafard J, Robitaille R, Vendittoli PA, Lévesque S, de Denus S. Oral ferrous sulfate does not increase preoperative hemoglobin in patients scheduled for hip or knee arthroplasty. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:764–770. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Li H, Li B, Wang Y, Jiang S, Jiang L. Efficacy and safety of iron supplementation for the elderly patients undergoing hip or knee surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Surg Res. 2011;171:e201–e207. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews CM, Lane DW, Bradley JG. Iron pre-load for major joint replacement. Transfus Med. 1997;7:281–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.1997.d01-42.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alsaleh K, Alotaibi GS, Almodaimegh HS, Aleem AA, Kouroukis CT. The use of preoperative erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) in patients who underwent knee or hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1463–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keating EM, Callaghan JJ, Ranawat AS, Bhirangi K, Ranawat CS. A randomized, parallel-group, open-label trial of recombinant human erythropoietin vs preoperative autologous donation in primary total joint arthroplasty: effect on postoperative vigor and handgrip strength. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doodeman HJ, van Haelst IM, Egberts TC, Bennis M, Traast HS, van Solinge WW, Kalkman CJ, van Klei WA. The effect of a preoperative erythropoietin protocol as part of a multifaceted blood management program in daily clinical practice (CME) Transfusion. 2013;53:1930–1939. doi: 10.1111/trf.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couvret C, Laffon M, Baud A, Payen V, Burdin P, Fusciardi J. A restrictive use of both autologous donation and recombinant human erythropoietin is an efficient policy for primary total hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:262–271. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000118165.70750.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bou Monsef J, Figgie MP, Mayman D, Boettner F. Targeted pre-operative autologous blood donation: a prospective study of two thousand and three hundred and fifty total hip arthroplasties. Int Orthop. 2014;38:1591–1595. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatzidakis AM, Mendlick RM, McKillip T, Reddy RL, Garvin KL. Preoperative autologous donation for total joint arthroplasty. An analysis of risk factors for allogenic transfusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:89–100. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Billote DB, Glisson SN, Green D, Wixson RL. A prospective, randomized study of preoperative autologous donation for hip replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1299–1304. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belmont PJ, Goodman GP, Hamilton W, Waterman BR, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ. Morbidity and mortality in the thirty-day period following total hip arthroplasty: risk factors and incidence. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:2025–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]