Abstract

Retinoic acid (RA)3 is a critical regulator of the intestinal adaptive immune response. However, the intrinsic impact of RA on B cell differentiation in the regulation of gut humoral immunity in vivo has never been directly shown. To address this issue, we have been able to generate a mouse model where B-cells specifically express a dominant negative receptor α for RA. Here, we show that the silencing of RA signaling in B-cells reduces the numbers of IgA+ antibody secreting cells (ASC) both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that RA has a direct effect on IgA plasma cell (PC) differentiation. Moreover, the lack of RA signaling in B-cells abrogates Ag-specific IgA responses after oral immunization and affects the microbiota composition. In conclusion, these results suggest that RA signaling in B-cells through the RA receptor α is important to generate an effective gut humoral response and to maintain a normal microbiota composition.

Introduction

All-trans retinoic acid (RA) is the main metabolite of vitamin A involved in immune regulation (1), where its primary function is to regulate gene transcription via binding to the nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoic X receptors (1). It has been shown that vitamin A deficiency results in low IgA titers in the intestine, which is correlated with low IgA plasma cell numbers in the gut (2-4). Consistent with the effect of RA in IgA differentiation, it has been demonstrated that oral doses of RA agonists in rats increase IgA titers, iNOS expression and nitrite/nitrate levels, which are important for IgA class switching (5-7). However, it is not known whether this is due to a direct effect on B-cells or an indirect effect through follicular T cells and dendritic cells, which could support IgA-PC differentiation in the gut. We have used a mouse model in which RAR-α signaling is inhibited specifically in B-cells by overexpressing a dominant negative form of RARα. Using this model, we observed that the lack of RA signaling in B-cells abrogated Ag-specific IgA responses after oral immunization and altered microbiota composition. In summary, these results definitively establish that RA signaling in B-cells are critical in generating an effective gut humoral response and for the maintenance of a normal microbiota composition.

Material and Methods

Mice and Immunizations

CD19Cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. The dnRARα mice have been previously described (8). Mice aged 8–10 weeks were immunized with 10 μg of the hapten (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl-cholera toxin (NP-CT) (provided by Nils Lycke) as described previously (9). These studies were approved and conducted in accredited facilities in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (Home Office license number PPL 70/7102). All animals were co-housed and maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at King’s College London.

Tissue preparation, flow cytometry and microscopy/immunofluorescence

Tissues were processed and single cell suspensions were prepared and stained with antibodies for flow cytometry as well as for microscopy as described previously described (10, 11). B-cells were cultured in vitro as reported before (12). For the analysis of IgA binding bacteria, preparation of the stool, staining and acquisition were done as described previously (13).

Real Time PCR

Total RNA extraction, real-time quantification and analysis was performed as previously described (11). TaqMan gene expression assay for mouse Aicda (Mm00507774_m1) was multiplexed with GAPDH endogenous control probe (4352339E) (Applied Biosystem).

ELISA and ELISPOT Analysis

Gut lavages and serums were used to assess NP-IgA, IgA and IgG1 titers by ELISA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Mouse IgG1/IgA total ELISA Ready-SET-Go, eBioscience). Single cells preparations were obtained from MLN, PP, spleen and small intestinal lamina propria (sLP) and the number of NP-IgA or total IgA-ASC was determined by ELISPOT as reported previously (9, 11).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) combined with flow cytometry

Stool samples were collected and fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) combined with flow cytometry was performed as previously described (14). The EUB 338 probe (FITC labelled) was used as the positive control probe, the NON 338 probe (Cy5 labelled) as the negative control and specific probes (Cy5 labelled) were used for identification of sub-groups (15).

Results and Discussion

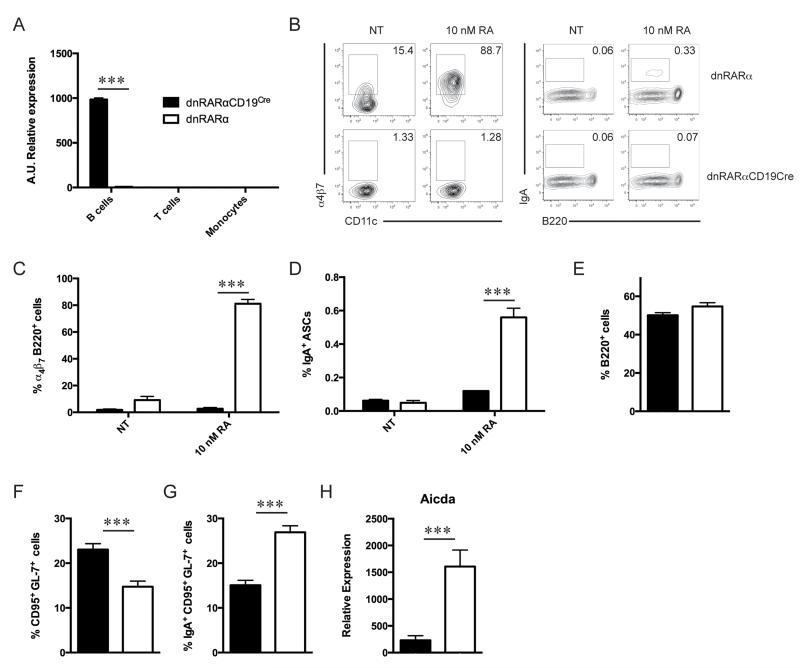

To analyze the functional impact of intrinsic RA signaling during B-cell differentiation, a dominant negative form of RARα was overexpressed in B-cells by interbreeding dnRARαfl/fl (8) mice with CD19Cre mice (hereafter denoted dnRARαCD19Cre). Analysis by quantitative PCR showed that only B-cells from dnRARαCD19Cre mice expressed the dnRARα form (Fig. 1A). To test that our model was able to inhibit RA signaling in B-cells, we performed in vitro culture experiments, as previously described (12). Briefly, splenic B-cells from dnRARαCD19Cre or dnRARα mice were enriched and activated in vitro with anti-mouse IgM in the presence or absence of 10nM of RA. Our results showed that when RA signaling was abrogated in B-cells, these cells were not able to induce α4β7 expression (Fig. 1B and 1C) nor generate IgA-ASC (Fig. 1B and 1D) compared to control cells. These data demonstrate that RA signaling is necessary to induce gut homing receptors in B-cells and IgA-PC differentiation in vitro, which is consistent with several independent reports (4, 16-18).

FIGURE 1. RA signaling in B-cells is essential to induce α4β7 expression and IgA PCs.

(A) dnRARα gene expression from purified splenic B, T-cells and monocytes from dnRARαCD19Cre mice or and littermate controls. (B) Representative dot plots of α4β7+ B-cells and IgA+ PCs from splenic B-cells from dnRARαCD19Cre and littermate controls after 5 days of culture with anti-mouse IgM in the presence or absence of 10 nM RA. For the analysis of α4β7, the cells were gated in live B220+ B-cells (and CD11c− to discard DCs) and for the detection of IgA+ ASC the gates were live B220− CD138+ cells. (C) Quantification of α4β7 expression in live B220+ B-cells. (D) Percentage of IgA+ PCs in live B220− CD138+ cells. (E, F and G) Analysis of B-cells from PP of dnRARαCD19Cre mice was performed. Percentage of B220+ B-cells (E), percentage of GC B (F) and IgA+ GC B-cells (G) are shown. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and gated in live B220+ B-cells. For the detection of IgA+ GC B cells, cells were gated as live B220+ CD95+ GL-7+. Littermates were used as a control. (H) Aicda gene expression was analyzed in GC B-cells from PP of dnRARαCD19Cre and control mice by quantitative PCR. Bar graph represent mean ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001; n = 9 to 10 mice/group.

It has been previously demonstrated that vitamin A deficiency affects generation of IgA-ASC in the gut, however, it is unknown whether RA has a direct effect on B-cells in vivo. Therefore, we evaluated the development of germinal center (GC) B-cells in Peyer’s Patches (PP) of dnRARαCD19Cre mice. To exclude variation due to housing conditions, in all in vivo experiments, dnRARαCD19Cre mice and littermate controls were co-housed. We observed that the number of PP, the percentage as well as the absolute number of B220+ cells in PP from dnRARαCD19Cre mice were normal compared to control mice (Fig. 1E, and data not shown). We also observed an increase in the percentage and absolute number of CD95+ GL-7+ GC B-cells in the PP from dnRARαCD19Cre mice (Fig. 1F and data not shown). Surprisingly, we found a reduction in IgA+ GC B-cells as a percentage and absolute number in PP of dnRARαCD19Cre mice (Fig. 1G and data not shown). In addition, Aicda gene expression analyzed by quantitative PCR was lower in GC B-cells from PP of dnRARαCD19Cre when compared to that from control mice (Fig. 1H), suggesting that the IgA+ GC B-cells reduction observed was due to a reduction in isotype switching. Taken together, these data indicate that RA signaling in B-cells is necessary to maximize the number and frequency of IgA+ GC B-cells.

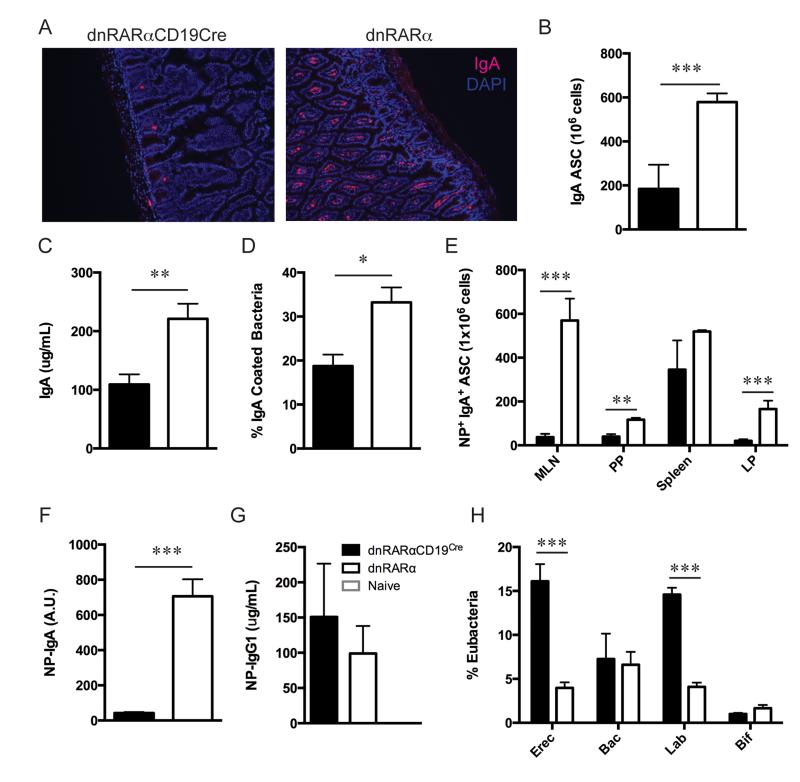

Since RA signaling in B-cells is important for the induction of IgA+ GC B-cells in PP, we analyzed its role in the generation of IgA-ASCs. We found a drastic reduction in IgA-ASCs number in the small intestine of dnRARαCD19Cre mice compared to control mice (Fig. 2A and 2B). This reduction was correlated with low IgA titers found in intestinal secretions from dnRARαCD19Cre mice (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, we also observed a reduction in the percentage of IgA bound to bacteria (Fig. 2D). We then explored the immune response to the well-characterized hapten NP-CT (9). Following NP-CT oral immunization, specific IgA responses in the small intestine of dnRARαCD19Cre and control mice were analyzed. Frequency of NP-specific ASCs in the sLP, PP and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) was reduced when RA signaling was abrogated in B-cells (Fig. 2E). We also observed a reduction in NP-IgA titers found in the stool of dnRARαCD19Cre compared to control mice (Fig. 2F), whereas systemic NP-IgG1 titer and frequency of NP-specific IgA−ASCs in the spleen remained unaltered (Fig. 2E and 2G). In addition, we did not observe an accumulation of NP-IgM ASC in the gut (data not shown). Together, these results indicate that RA signaling in B-cells plays an important role in generating antigen-specific IgA responses in the gut.

FIGURE 2. RA signaling in B-cells is required for effective IgA-PC differentiation and normal microflora maintenance in the gut.

(A) Histology showing IgA+ cells in sLP from dnRARαCD19Cre and control mice (n = 4/group). (B) Single cell suspensions were obtained from sLP of dnRARαCD19Cre mice and littermate controls and the number of IgA-ASC was determined by ELISPOT. (C) Quantification of luminal IgA levels from sLP of dnRARαCD19Cre mice measured by ELISA (n = 8/group). (D) Percentage of IgA binding bacteria from small intestine of dnRARαCD19Cre and littermate controls. (E) Mice were orally immunized two times with NP-CT or saline solution alone. Cells were then, isolated from MLN, PP, spleen and LP of the small intestine and the number of NP-IgA+ PC was determined by ELISPOT. (F) Quantification of NP-IgA titers in the stool from sLP of dnRARαCD19Cre mice and controls measured by ELISA. (G) Quantification of NP-IgG1 titers in serum by ELISA. (H) Fecal samples were collected from dnRARαCD19Cre and control mice and the different bacterial groups (BAC= Bacteroides and Prevotella, EREC= Lachnospiraceae, BIF= Bifidobacterium, LAB= Lactobacillus & Streptococcus) were identified by FISH-Flow (n = 14/group). Bar graph represent mean ± SEM. *, P<0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The importance of crosstalk between the microbiome and the immune system in IgA mediated intestinal homeostasis has been previously described (19). As dnRARαCD19Cre and control mice have different humoral IgA responses, we investigated whether the gut microflora was altered in these mice. To address this, fecal samples from co-housed dnRARαCD19Cre and dnRARα mice were analyzed. Composition of gut microbiota was significantly different between dnRARαCD19Cre and control mice (Fig. 2H). The dnRARαCD19Cre mice displayed an increase in the proportion of adherent bacteria Lachnospiraceae (Erec482+) and Lactobacillus/Streptococcus (Lab158+) groups compared to control mice, which has been suggested to be associated with colorectal adenomas (20). Together, our results demonstrate that altered IgA responses, due to lack of RA signaling in B cells, significantly affects the symbiotic relations between host and commensal bacteria in the gut.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first time that a direct effect of RA signaling in B-cells has been shown in vivo. Our results demonstrate that RA signaling in B-cells is not essential for their homing to PP. However, it is necessary to maintain an optimal IgA humoral immune response and a normal microbiota composition in the gut. Overall, these results further support the potential use of RA as an adjuvant in preventing dietary allergies as previously suggested by others (21, 22).

Footnotes

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust grant (WT091823/z/10/z) to R.J.N. The work was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Abbreviations: RA, retinoic acid; PP, Peyer’s Patch; ASC, antibody secreting cells; PC, plasma cells; LP, lamina propria; MLN, mesenteric lymph node; GC, Germinal Center; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; dn, dominant negative; NP, hapten (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl; CT, cholera toxin; FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridisation.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Journal of Immunology.

Reference

- 1.Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2008;8:685–698. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDermott MR, Mark DA, Befus AD, Baliga BS, Suskind RM, Bienenstock J. Impaired intestinal localization of mesenteric lymphoblasts associated with vitamin A deficiency and protein-calorie malnutrition. Immunology. 1982;45:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjersing JL, Telemo E, Dahlgren U, Hanson LA. Loss of ileal IgA+ plasma cells and of CD4+ lymphocytes in ileal Peyer’s patches of vitamin A deficient rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:404–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.02009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mora JR, Iwata M, Eksteen B, Song S-Y, Junt T, Senman B, Otipoby KL, Yokota A, Takeuchi H, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Rajewsky K, Adams DH, von Andrian UH. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuwabara K, Shudo K, Hori Y. Novel synthetic retinoic acid inhibits rat collagen arthritis and differentially affects serum immunoglobulin subclass levels. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seguin-Devaux C, Devaux Y, Latger-Cannard V, Grosjean S, Rochette-Egly C, Zannad F, Meistelman C, Mertes P-M, Longrois D. Enhancement of the inducible NO synthase activation by retinoic acid is mimicked by RARalpha agonist in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;283:E525–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devaux Y, Grosjean S, Seguin C, David C, Dousset B, Zannad F, Meistelman C, De Talancé N, Mertes PM, Ungureanu-Longrois D. Retinoic acid and host-pathogen interactions: effects on inducible nitric oxide synthase in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;279:E1045–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajaii F, Bitzer Z, Xu Q, Sockanathan S. Expression of the dominant negative retinoid receptor, RAR403, alters telencephalic progenitor proliferation, survival, and cell fate specification. Developmental biology. 2008;316:371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergqvist P, Stensson A, Hazanov L, Holmberg A, Mattsson J, Mehr R, Bemark M, Lycke NY. Re-utilization of germinal centers in multiple Peyer's patches results in highly synchronized, oligoclonal, and affinity-matured gut IgA responses. Mucosal Immunology. 2012;6:122–135. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elgueta R, Sepulveda FE, Vilches F, Vargas L, Mora JR, Bono MR, Rosemblatt M. Imprinting of CCR9 on CD4 T cells requires IL-4 signaling on mesenteric lymph node dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:6501–6507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elgueta R, Marks E, Nowak E, Menezes S, Benson M, Raman VS, Ortiz C, O’Connell S, Hess H, Lord GM, Noelle R. CCR6-Dependent Positioning of Memory B Cells Is Essential for Their Ability To Mount a Recall Response to Antigen. J Immunol. 2015;194:505–513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mora J, Iwata M, Eksteen B, Song S, Junt T, Senman B, Otipoby K, Yokota A, Takeuchi H, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawamoto S, Tran TH, Maruya M, Suzuki K, Doi Y, Tsutsui Y, Kato LM, Fagarasan S. The Inhibitory Receptor PD-1 Regulates IgA Selection and Bacterial Composition in the Gut. Science. 2012;336:485–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1217718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigottier Gois L, Bourhis AG, Gramet G, Rochet V, Doré J. Fluorescent hybridisation combined with flow cytometry and hybridisation of total RNA to analyse the composition of microbial communities in human faeces using 16S rRNA probes. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2003;43:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2003.tb01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell N, Walker AW, Stolarczyk E, Canavan JB, Gökmen MR, Marks E, Jackson I, Hashim A, Curtis MA, Jenner RG, Howard JK, Parkhill J, MacDonald TT, Lord GM. The Transcription Factor T-bet Regulates Intestinal Inflammation Mediated by Interleukin-7 Receptor+ Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity. 2012;37:674–684. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Kitamura H, Maruya M, Kinoshita K, Ivanov II, Itoh K, Littman DR, Fagarasan S. Requirement for lymphoid tissue-inducer cells in isolated follicle formation and T cell-independent immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity. 2008;29:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, Maruya M, Kawamoto S, Sitnik K, Kitamura H, Agace WW, Fagarasan S. The sensing of environmental stimuli by follicular dendritic cells promotes immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity. 2010;33:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe K, Sugai M, Nambu Y, Osato M, Hayashi T, Kawaguchi M, Komori T, Ito Y, Shimizu A. Requirement for Runx proteins in IgA class switching acting downstream of TGF-beta 1 and retinoic acid signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:2785–2792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsiao W, Battle M, Yao M, Gavrilova O, Orandle M, Mayer L, Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD, Fraser-Liggett C, Shulzhenko N, Morgun A, Matzinger P. Crosstalk between B lymphocytes, microbiota and the intestinal epithelium governs immunity versus metabolism in the gut. Nat Med. 2011;17:1585–1593. doi: 10.1038/nm.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen XJ, Rawls JF, Randall TA, Burcall L, Mpande C, Jenkins N, Jovov B, Abdo Z, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Molecular characterization of mucosal adherent bacteria and associations with colorectal adenomas. Gut Microbes. 2014;1:138–147. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indrevær RL, Holm KL, Aukrust P, Osnes LT, Naderi EH, Fevang B, Blomhoff HK. Retinoic acid improves defective TLR9/RP105-induced immune responses in common variable immunodeficiency-derived B cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:3624–3633. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Depaolo RW, Abadie V, Tang F, Fehlner-Peach H, Hall JA, Wang W, Marietta EV, Kasarda DD, Waldmann TA, Murray JA, Semrad C, Kupfer SS, Belkaid Y, Guandalini S, Jabri B. Co-adjuvant effects of retinoic acid and IL-15 induce inflammatory immunity to dietary antigens. Nature. 2011;471:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature09849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]