Abstract

Background:

The diagnostic accuracy of frozen section as an important source of information in surgical pathology is important not only in the management of surgical patients but also as a measure of quality control in surgical pathology. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of frozen sections over a 6-year period in a teaching hospital in Iran.

Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed frozen sections performed in the Pathology Department of Taleghani Hospital (Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences), Tehran, Iran from 2007 to 2013. The results were compared to the permanent sections to evaluate diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity and specificity, of frozen section test. Discordant cases were reassessed to find the reasons for discrepancy.

Results:

A total of 306 frozen section specimens from 176 surgical cases were evaluated. In eleven specimens (3.59%) the diagnoses were deferred. Of the remaining 295 specimens, 6 (2.03%) were discordant and 289 (97.96%) were concordant to permanent diagnoses. Specimens were primarily from the head & neck, thyroid, ovary, parathyroid and lymph nodes. The overall sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the frozen section compared to permanent section (as gold standard) were 92.95%, 99.55%, 98.50% and 97.80% respectively. Of the 6 discordant diagnoses, two (33.3%) were due to sampling error and four (66.6%) were due to interpretative errors.

Conclusion:

Frozen section is an accurate and valuable test and can be relied on in surgical managements. The results of this study also confirm that the accuracy of frozen section diagnosis in our institution compares well with internationally published rates.

Key Words: Frozen Section, Permanent Section, Accuracy, Discrepancies

Introduction

Frozen section plays a major role in the surgical management of patients with neoplastic and non-neoplastic disease. Since its introduction in the late 20th century, the use of frozen section has spectacularly increased. It provides the surgeon with important pathologic information while the patient is on the operating table (1). There are many indications for performing frozen section, including determination of the nature and extent of a lesion, evaluation of surgical margins and assessment of adequacy of tissue for diagnosis (2). However, the main purpose of frozen section is to guide the surgeon making immediate decision as the extent and or adequacy of surgical procedure, thus decreasing the need for reoperation (3).

The surgeon’s confidence in frozen section results, depends on the diagnostic accuracy of this procedure (1). Frozen section diagnosis is usually compared to permanent section diagnosis to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy. Evaluating discrepancies, identifying deficiencies and resolving the underlying problems can improve the accuracy of frozen section (2). Reasons for diagnostic discrepancy generally fall into one of the following categories: technical problems, sampling errors or interpretation errors (4).

It is well established that periodic review of frozen sections will result in improvement of performance. Therefore, it has been suggested to place periodic review as part of quality assurance in pathology departments (5).

In this study we have reviewed frozen sections performed in our institute during a 6 year period to assess the diagnostic accuracy and determine the rates of deferred and discordant results as well as the reasons for discrepancy.

Material and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the frozen section cases performed in Pathology Laboratory, Taleghani Hospital, Tehran, Iran from April 2007 to March 2013. This period was chosen because electronic data of frozen section cases was available since 2007. Taleghani hospital is a teaching hospital affiliated by Shahid Beheshti University of medical sciences.

Tissue specimens sent for frozen section were frozen and cut by a cryostat machine: Reichert-Jung until 2012 and since then Tissue-Tech Cryo 3 (Sakura). The sections were fixed on glass slides and stained by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). The remaining tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, processed, embedded in paraffin and stained with H&E.

Patient files in the pathology department provided data regarding the frozen section cases. The frozen section diagnoses were compared to that of the permanent sections, to assess the accuracy of the technique. The frozen section results in comparison to final diagnoses were then categorized into three groups: concordant, discordant and deferred. With a proper frozen section study, diagnoses were considered as concordant if there was agreement and discordant if there was disagreement with permanent section diagnoses. Deferred cases were defined as indeterminate diagnoses at the time of frozen section examination. Deferral rate was not included in the calculation of accuracy. Finally, discordant cases were reviewed and causes of discrepancy were recorded.

Results

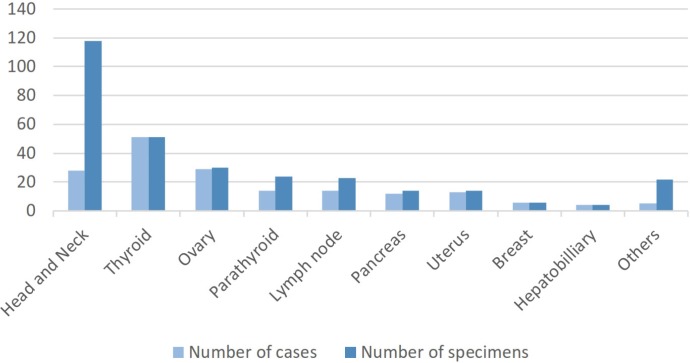

In the 6-year period of our study, 306 frozen section specimens were received from 176 surgical cases. The submitted tissues for frozen section were primarily from head/neck, thyroid, ovary, parathyroid and lymph nodes (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of frozen sections, by tissue type

Indications for frozen section were 1) verification and categorization of neoplasms in 195 (63.7%), 2) evaluation of margins in 100 (32.7%) and, 3) determination of the organ of origin in 11 (3.6%) of cases.

Of the 306 cases, in 11 (3.59%) cases the diagnosis of frozen section was deferred to permanent section. Of the remaining 295 cases, frozen section and permanent section diagnoses were concordant in 289 (97.96%) and discordant in 6 (2.03%) of cases (Table1). Among discordant cases, two were parotid tissue, and one each as thyroid, pancreas, cervical lymph node and uterus (Table.2).

Table 1.

Frequency of concordant, discordant and deferral cases

| Tissue Type | Number of cases | Concordant | Discordant | Deferred |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head & Neck | 118 | 113 | 2 | 3 |

| Thyroid | 51 | 47 | 1 | 2 |

| Ovary | 30 | 28 | 0 | 2 |

| Parathyroid | 24 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymph Node | 23 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| Pancreas | 14 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| Uterus | 14 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| Breast | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatobilliary | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Others | 22 | 20 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 306 | 289 | 6 | 11 |

Table 2.

Discordant cases

| Tissue | Frozen section diagnosis | Permanent diagnosis | Reason for discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid | Cyst lining with Hurthle cells without any papillary change | Hurthle cell tumor | Misinterpretation |

| Parotid | Negative for malignancy | Acinic cell carcinoma | Sampling error |

| Parotid | Reactive lymph node | Lymphoma | Misinterpretation |

| Pancreas | Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm | Reactive lymph node | Misinterpretation |

| lymph node (cervical) | Reactive lymph node | Squamous cell carcinoma | Misinterpretation |

| Uterus | Negative for malignancy | Adenocarcinoma | Sampling error |

The reason for discrepancy was also assessed by reviewing the frozen section slides. Of the six discordant cases, the reason for discrepancy was sampling error in two (33.3%) and misinterpretation in four (66.6%).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of frozen section in comparison with permanent section were 92.95%, 99.55%, 98.50% and 97.80% respectively.

Discussion

In the present study we reviewed the frozen sections performed in Pathology Department of Taleghani Hospital in a 6 year period to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the test in this institution. We also reviewed the discordant cases to find the reasons for discrepancy. Total number of concordant and discordant cases were 289 (97.96%) and 6 (2.03%) respectively.

Deferred rate is also a valid parameter of quality assurance. Our study showed 11 (3.59%) deferral cases which is comparable to previously published studies with a deferred rate ranging from 0.04% to 6.7% (6). Deferral rates may vary according to clinical expertise and also clinical setting and the type of specimens encountered (7). In our study, deferral cases were mostly from head & neck, thyroid and ovary.

Wendum and Flejou evaluated the accuracy of frozen section in 847 consecutive specimens in a teaching hospital (8). Their results showed concordant, discordant and deferred rates of 92.6%, 1.7% and 5.8% respectively that is comparable with our results. Discordant rate in our study is also comparable to other previously published studies reporting discordant rates ranging from 1.4 to 11.8% with a mean of 3.17% (-, 6, 7, -). The reasons for discordant cases were misinterpretation in 4 (66.6%) and sampling error in 2 (33.3%) cases. Of these, there was one false positive, which was the result of sampling error. The other 5 discordant cases were false negatives due to sampling error in one case and misinterpretation in the others. Other previous studies show misinterpretation as the main cause for discrepancy followed by sampling error (2, 8, 14, 18). Our results show a higher rate of false negative than false positive results, which is comparable to previous studies.

Experience plays a major role in interpretation of frozen sections, there is a lower deferred and error rate when specimens are interpreted by more experienced pathologists (1). A study has shown junior residents make higher percentage of inaccurate diagnoses which is improved with additional training (22). Evaluation of the specimens by two observers or even three, when there is uncertainty, reduces the rate of error (23). We find it unlikely for inexperience to be responsible for error rates in our study since all diagnoses on frozen sections made by residents was reviewed by attending pathologists with extensive experience.

Conclusion

Frozen section is an accurate and reliable test. More accurate sampling plus better communication between pathologist and surgeon is recommended to help reducing the rate of discordant and deferral cases. In addition, reevaluation of the interpretations by a second pathologist especially when there is uncertainty is helpful in reducing both discordant and deferral rates.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Mehrdad Nadji for his constructive comments and Pathology Department staff of Taleghani Hospital for their cooperation in data collection. This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Howanitz PJ, Hoffman GG, Zarbo RJ. The accuracy of frozen-section diagnoses in 34 hospitals. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990 Apr;114(4):355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahe E, Ara S, Bishara M, Kurian A, Tauqir S, Ursani N, et al. Intraoperative pathology consultation: error, cause and impact. Can J Surg. 2013 Jun;56(3):E13–8. doi: 10.1503/cjs.011112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shrestha S, Basyal R, Pathak TSS, Lee M, Dhakal H, Pun C, et al. Comparatve Study of Frozen Secton Diagnoses with Histopathology. Post Graduate Medical of NAMS. 2009;9(02):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaafar H. Intra-operative frozen section consultation: concepts, applications and limitations. Malays J Med Sci. 2006 Jan;13(1):4–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raab SS, Tworek JA, Souers R, Zarbo RJ. The value of monitoring frozen section-permanent section correlation data over time. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(3):337–42. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-337-TVOMFS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chbani L, Mohamed S, Harmouch T, El Fatemi H, Amarti A. Quality assessment of intraoperative frozen sections: An analysis of 261 consecutive cases in a resource limited area: Morocco. Health. 2012;4(7):433–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gephardt GN, Zarbo R. Interinstitutional comparison of frozen section consultations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120(9):804–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wendum D, Flejou J. Quality assessment of intraoperative frozen sections in a teaching hospital: an analysis of 847 consecutive cases. Ann Pathol. 2003;23(5):393–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarbo RJ, Hoffman GG, Howanitz PJ. Interinstitutional comparison of frozen-section consultation. A College of American Pathologists Q-Probe study of 79,647 consultations in 297 North American institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115(12):1187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad Z, Barakzai MA, Idrees R, Bhurgri Y. Correlation of intra-operative frozen section consultation with the final diagnosis at a referral center in Karachi, Pakistan. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51(4):469–73. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.43733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aijaz F, Muzaffar S, Hussainy AS, Pervez S, Hasan SH, Sheikh H. Intraoperative frozen section consultation: an analysis of accuracy in a teaching hospital. J Pak Med Assoc. 1993 Dec;43(12):253–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerski CT, Lopes MF, Kliemann LM, Zimmermann HH. Transoperative anatomopathologic examinations: quality control. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1994;40(4):243–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donisi PM. Problems and limitations of frozen section diagnosis. A review of 470 consecutive cases. Pathologica. 1991;83(1086):467–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoo JJ. An audit of intraoperative frozen section in Johor. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(1):50–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigrisoli E, Gardini G. Quality control of intraoperative diagnosis. Annual review of 1490 frozen sections. Pathologica. 1994;86(2):191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novis DA, Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Interinstitutional comparison of frozen section consultation in small hospitals: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 18,532 frozen section consultation diagnoses in 233 small hospitals. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120(12):1087–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers C, Klatt EC, Chandrasoma P. Accuracy of frozen-section diagnosis in a teaching hospital. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111(6):514–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White VA, Trotter MJ. Intraoperative consultation/final diagnosis correlation: relationship to tissue type and pathologic process. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(1):29–36. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-29-IFDCRT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.da Silva RD, Souto LR, Matsushita Gde M, Matsushita Mde M. Diagnostic accuracy of frozen section tests for surgical diseases. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2011;38(3):149–54. doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912011000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Özdamar S, Bahadir B, Ekem T, Kertis G, Gün B, Numanoðlu G. Frozen section experience with emphasis on reasons for discordance. Turk J Cancer. 2006;36(4):157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dankwa EK, Davies JD. Frozen section diagnosis: an audit. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38(11):1235–40. doi: 10.1136/jcp.38.11.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beland MD, Anderson TJ, Atalay MK, Grand DJ, Cronan JJ. Resident Experience Increases Diagnostic Rate of Thyroid Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsies. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(11):1490–4. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffin CM. Pediatric surgical pathology: pitfalls and strategies for error prevention. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(5):610–2. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-610-PSPPAS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]