Abstract

Objectives. We explored how changes in insurance coverage contributed to recent nationwide decreases in newborn circumcision.

Methods. Hospital discharge data from the 2000–2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample were analyzed to assess trends in circumcision incidence among male newborn birth hospitalizations covered by private insurance or Medicaid. We examined the impact of insurance coverage on circumcision incidence.

Results. Overall, circumcision incidence decreased significantly from 61.3% in 2000 to 56.9% in 2010 in unadjusted analyses (P for trend = .008), but not in analyses adjusted for insurance status (P for trend = .46) and other predictors (P for trend = .55). Significant decreases were observed only in the South, where adjusted analyses revealed decreases in circumcision overall (P for trend = .007) and among hospitalizations with Medicaid (P for trend = .005) but not those with private insurance (P for trend = .13). Newborn male birth hospitalizations covered by Medicaid increased from 36.0% (2000) to 50.1% (2010; P for trend < .001), suggesting 390 000 additional circumcisions might have occurred nationwide had insurance coverage remained constant.

Conclusions. Shifts in insurance coverage, particularly toward Medicaid, likely contributed to decreases in newborn circumcision nationwide and in the South. Barriers to the availability of circumcision should be revisited, particularly for families who desire but have less financial access to the procedure.

There is renewed interest in circumcision in the United States because of the increasing evidence for reduced risks of sexually transmitted infections, including human papillomavirus (HPV), genital herpes, and HIV; urinary tract infections in infancy; balanoposthitis; and penile cancer for males and cervical cancer in their female partners.1,2 The procedure is not completely without risk, however, as circumcision may result in minor complications (most commonly bleeding and infection) and, albeit rarely, serious complications that require surgery.3,4

Recent recognition of the benefits of circumcision has rekindled discussion about the need for updated recommendations for newborn circumcision in the United States.5 Because the health benefits outweigh the risks and therefore warrant reimbursement, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued guidance in 2012 that explicitly recommended access to newborn circumcision for families who desired the procedure.3 In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently issued the agency’s first-ever draft guidelines on circumcision, which state that parents of newborn males should be informed of the medical benefits of the procedure as well as the risks involved.6

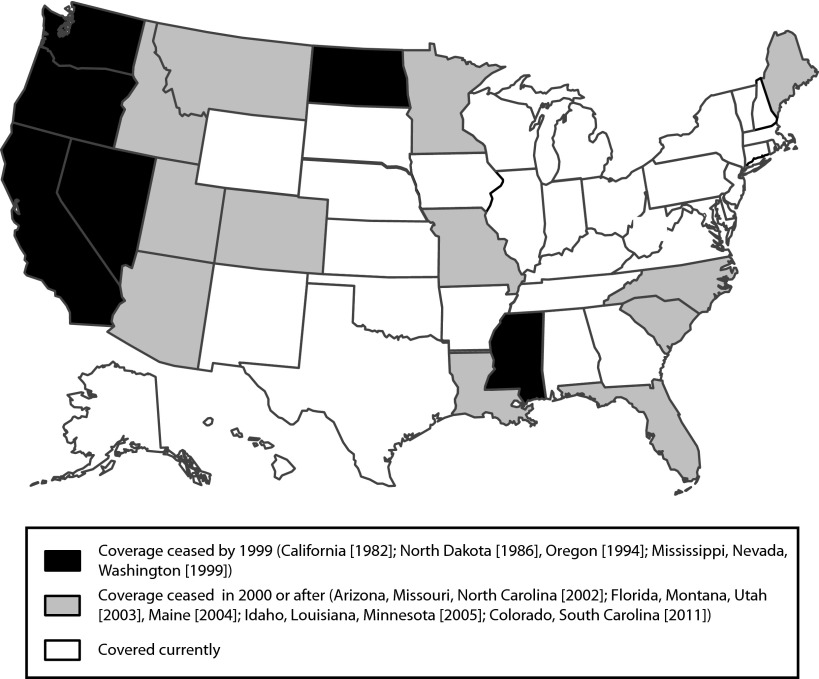

Circumcision incidence has decreased in the United States from around 60% in 2000 to 56% in 20087,8 after increasing during the late 1980s and 1990s.9,10 The decrease in circumcision nationwide since 2000 coincides with the release of an earlier, more neutral position statement regarding the risk–benefit ratio for neonatal circumcision issued by AAP5 that was reaffirmed in 2005.11 The previous AAP statement, although acknowledging the potential medical benefits of circumcision, indicated that the procedure was not essential to the child’s well-being and that the decision was best left to parents. After the earlier guidance was released, many states ceased Medicaid coverage for circumcision procedures. Overall, at the time of this writing, 18 states have discontinued Medicaid coverage, including 12 that have ceased such coverage since 1999 (Figure 1).12,13 Whereas states that discontinued coverage were initially concentrated in the West, in recent years states across all regions have discontinued Medicaid coverage, particularly in the South, where 5 states have ceased coverage. This change in Medicaid coverage may be in response to earlier recommendations regarding newborn circumcision from AAP5 and other professional organizations.12,14–17

FIGURE 1—

Medicaid coverage of newborn circumcision procedures by state: United States.

Because little research to date has explored factors that could explain this decline, we examined trends in circumcision during the period between issuance of the previous and current AAP guidance and assessed how shifts in insurance coverage (from private insurance to Medicaid) may have contributed to the recent nationwide decrease in newborn circumcision.

METHODS

Hospital discharge data for male newborn birth hospitalizations were obtained from 2000 to 2010 from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is a research database produced annually through a partnership between the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and public and private state-level data collection organizations to provide nationwide estimates of inpatient care in the United States.18 It is the largest collection of all-payer data on inpatient care and provides information on demographics, diagnostic and procedural data, and facilities.

Through a stratified probability design, the NIS is constructed to approximate a 20% sample of all US community hospitals as defined by the American Hospital Association. The sampling frame consists of state-specific hospital discharge data provided to HCUP. The NIS includes all inpatient data from sampled institutions and annually includes approximately 1000 hospitals and more than 7 million discharge records.19 In 2010, 45 states contributed data, representing 96.8% of the US population.

Male newborn birth hospitalizations were identified using principal or secondary International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes 765.20, 795.29, and V30-V39.20 Circumcision procedures were identified by ICD-9-CM procedure code 64.0 (“Circumcision”). Patient- and hospital-level characteristics available as potential predictors of circumcision9,21 included region (Northeast, Midwest, South vs West), hospitalization location (urban vs rural), newborn health status (healthy full-term vs not), primary expected payer (private [i.e., commercial carriers and private health maintenance organizations and preferred provider organizations] vs nonprivate [i.e., Medicaid, Medicare, self-pay, no charge, and other] insurance), and birth year. Region and location were defined using standard definitions from the US Census Bureau. Newborns were classified as “healthy, full-term” if the diagnosis-related group code for normal newborn (391) on the discharge record revealed no indication of preterm birth (ICD-9-CM codes 765.21–765.28, 765.0x, 765.1x), inpatient infant death, or admission or transfer to another hospital, and were compared with those that were not.

Given our interest in examining how circumcision incidence was affected by increasing proportions of birth hospitalizations covered by Medicaid as opposed to private insurance, we limited expected primary payer for nonprivate insurance to hospitalizations with Medicaid coverage and excluded those for which the payer was reported as Medicare, self-pay, no charge, or other. Thus, we restricted further analyses to the remaining 92.2% of male birth hospitalizations that were covered by private or Medicaid insurance during the study period.

We also considered including race/ethnicity because of its association with newborn circumcision in previous US studies.21–24 However, race/ethnicity was missing in more than 20% of records in the NIS overall during the observation period, and the level of missingness varied widely both by region (from 5.8% in the Northeast to 51.7% in the Midwest) and year (from 25.3% in 2000 to 13.0% in 2010). Thus, we were unable to provide meaningful race- or ethnicity-specific estimates for circumcision incidence overall or by region in 10-year trend analyses.

Newborn circumcision is described by an incidence proportion (risk), and the appropriate measure of association is the risk ratio. Poisson regression modeling with a robust variance estimator has been recommended for estimating ratios of proportions from cross-sectional data,25,26 which is directly applicable to estimating risk ratios. This modeling was used to examine unadjusted and adjusted linear trends in circumcision incidence in the nationwide sample, with birth year as a continuous variable. The initial bivariate model examined year alone to assess the unadjusted trend in circumcision incidence, followed by multivariable models that examined the trend in incidence adjusted for each covariate individually (i.e., region, location of hospitalization, insurance type, and newborn health status). The final multivariable model examined the trend in incidence adjusted for all covariates in aggregate and provided adjusted risk ratios for associations between select characteristics and circumcision. Given our interest in payer- and region-specific trends in circumcision incidence, we repeated this modeling procedure separately for each payer type and geographic region.

Finally, we estimated the impact of temporal shifts in type of insurance coverage on the number of newborn circumcisions. Using data from the observed number of circumcisions procedures performed annually, we estimated the number expected to be performed from 2001 to 2010 based on a hypothetical scenario in which the proportion of hospitalizations covered by Medicaid remained the same throughout the 11-year period as observed in 2000. We then estimated the number of circumcisions annually by multiplying the observed number of newborn male birth hospitalizations by the observed incidence of circumcision in both private payer and Medicaid hospitalizations; however, we assumed the distribution of private and Medicaid insurance coverage for that year was identical to 2000. The difference between the estimated and observed number of circumcisions performed annually was then computed and summed across the observation period.

All analyses accounted for the complex sampling design of the NIS and were performed using SAS-Callable SUDAAN version 9.2 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC).

RESULTS

From 2000 to 2010, circumcisions were performed nationwide during approximately 12.3 million (56.9%) of 21.6 million male newborn birth hospitalizations covered by private insurance or Medicaid; the annual incidence decreased significantly from 61.3% in 2000 to 56.9% in 2010 (unadjusted P for trend = .008; Table 1). The decreasing linear trend in circumcision incidence observed in unadjusted analyses remained significant after individual bivariate adjustment for each covariate examined (i.e., region [P for trend = .002], hospital location [P for trend = .01], and newborn health status [P for trend = .01, not shown]), with 1 notable exception. This decreasing linear trend was no longer significant after individual adjustment for type of insurance coverage (P for trend = .46) and, likewise, multivariable adjustment for all 4 covariates (P for trend = .55; Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Trends in Incidence of Newborn Circumcision Nationwide and by Region: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2000–2010

| Circumcisions, % |

P for Trend |

|||||

| Region | 2000 | 2010 | Absolute Change, % | Percent Change, % | Unadjusted | Adjusteda |

| Nationwide | 61.3 | 56.9 | −4.4 | −7.2 | .008 | .55 |

| Northeast | 70.2 | 66.8 | −3.4 | −4.8 | .58 | .58 |

| Midwest | 78.0 | 76.6 | −1.4 | −1.8 | .98 | .19 |

| South | 66.3 | 57.0 | −9.3 | −14.0 | < .001 | .007 |

| West | 30.9 | 33.1 | +2.2 | +7.1 | .66 | .75 |

Adjusted for primary payer, hospital location, newborn health status, and (where applicable) geographic region.

Multivariable modeling further revealed, independent of birth year, circumcision incidence remained higher for newborn hospitalizations covered by private insurance compared with Medicaid (66.9% vs 44.0%; Table 2). The incidence was significantly higher among hospitalizations in the Midwest (76.3%), Northeast (66.9%), and South (60.2%) versus the West (28.5%). Other factors associated with increased circumcision incidence included birth in a rural hospital and being a full-term, healthy newborn.

TABLE 2—

Multivariable Analyses of Association Between Selected Characteristics and Incidence of Newborn Circumcision During Male Birth Hospitalizations: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2000–2010

| Nationwide (n = 21 637 809) |

Northeast (n = 3 656 583) |

Midwest (n = 4 654 474) |

South (n = 7 925 694) |

West (n = 5 401 057) |

||||||

| Hospitalization Characteristic | Circumcised, % | ARR (95% CI) | Circumcised, % | ARR (95% CI) | Circumcised, % | ARR (95% CI) | Circumcised, % | ARR (95% CI) | Circumcised, % | ARR (95% CI) |

| Primary payer | ||||||||||

| Private | 66.9 | 1.51 (1.47, 1.54) | 71.9 | 1.25 (1.20, 1.29) | 80.4 | 1.16 (1.14, 1.19) | 73.2 | 1.54 (1.48, 1.60) | 42.0 | 3.75 (3.38, 4.17) |

| Medicaid | 44.0 | 1.00 (Ref) | 57.7 | 1.00 (Ref) | 69.2 | 1.00 (Ref) | 48.1 | 1.00 (Ref) | 11.3 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Hospital location | ||||||||||

| Rural | 66.2 | 1.16 (1.13, 1.18) | 73.1 | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) | 80.5 | 1.07 (1.05, 1.10) | 68.2 | 1.24 (1.19, 1.29) | 28.1 | 1.13 (1.00, 1.29) |

| Urban | 55.6 | 1.00 (Ref) | 66.5 | 1.00 (Ref) | 75.5 | 1.00 (Ref) | 58.9 | 1.00 (Ref) | 28.5 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Newborn health status | ||||||||||

| Healthy, full-term | 59.8 | 1.19 (1.18, 1.20) | 69.9 | 1.15 (1.13, 1.17) | 80.2 | 1.19 (1.18, 1.21) | 64.3 | 1.22 (1.20, 1.24) | 29.9 | 1.19 (1.15, 1.22) |

| Not healthy, full-term | 50.2 | 1.00 (Ref) | 60.3 | 1.00 (Ref) | 66.8 | 1.00 (Ref) | 51.7 | 1.00 (Ref) | 25.1 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Geographic region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 66.9 | 2.28 (2.13, 2.43) | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Midwest | 76.3 | 2.57 (2.42, 2.74) | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| South | 60.2 | 2.17 (2.04, 2.32) | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| West | 28.5 | 1.00 (Ref) | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . |

Note. ARR = adjusted risk ratio; CI = confidence interval. Multivariable analyses of circumcision incidence adjusted for all variables listed in table and year of birth.

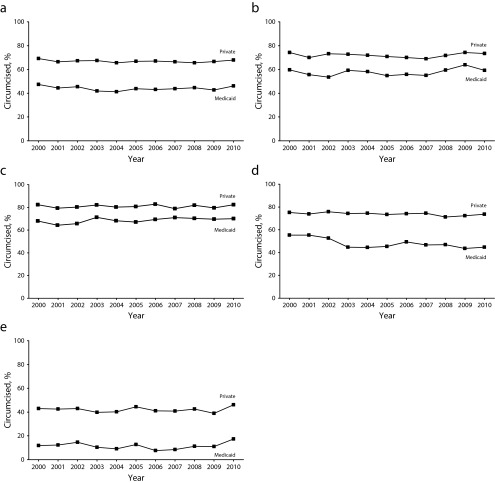

Regional trends in annual newborn circumcision incidence differed from the declining trend observed nationwide, with 1 exception. In the Northeast, Midwest, and West, there were no significant decreases in circumcision incidence from 2000 to 2010 in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses accounting for all covariates (Table 1; Figure 2b, 2c, and 2e). The exception was the South, where circumcision incidence decreased significantly overall (from 66.3% to 57.0%) in both unadjusted (P for trend < .001) and adjusted analyses (P for trend = .007; Table 1; Figure 2d). Moreover, circumcision incidence in the South significantly decreased only among hospitalizations with Medicaid (from 55.3% to 45.3%; adjusted P for trend = .005) but not among hospitalizations with private insurance (from 74.5% to 73.0%; adjusted P for trend = .13; Figure 2d).

FIGURE 2—

Incidence of newborn circumcision among male newborn hospitalizations by type of health insurance in (a) the United States, (b) Northeast, (c) Midwest, (d) South, and (e) West: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2000–2010.

In multivariable analyses conducted within each region that also adjusted for birth year, circumcision incidence remained consistently higher for hospitalizations with private insurance versus Medicaid (Table 2). As observed nationwide, being born in a rural hospital and healthy, full-term were both associated with increased circumcision incidence in each region.

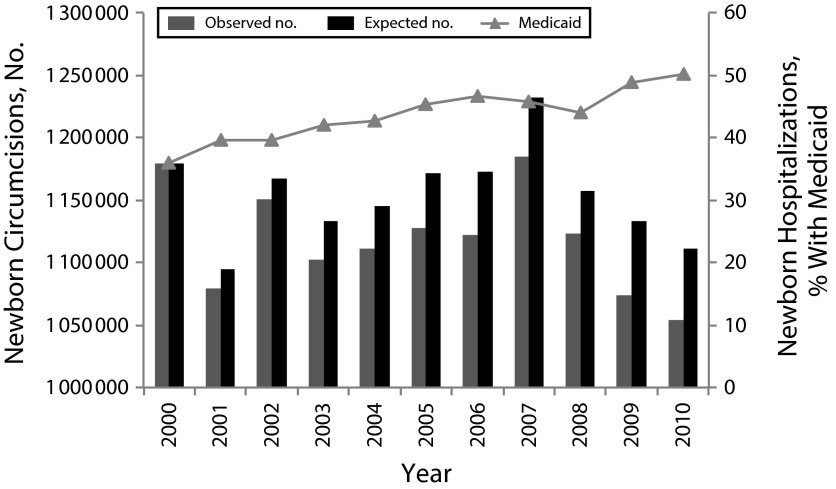

We examined nationwide and regional trends in the distribution of type of insurance coverage for male newborn birth hospitalizations during the observation period. From 2000 to 2010, there was a significant linear increase in the proportion of male newborn hospitalizations nationwide with Medicaid coverage (from 36.0% in 2000 to 50.1% in 2010; P for trend < .001). This temporal increase was significant for birth hospitalizations where circumcision was performed (from 27.8% to 40.6%) and where it was not (from 48.9% to 62.7%; P for trend < .001; not shown). Significant linear increases in the proportion of newborn birth hospitalizations with Medicaid coverage were also observed in each region from 2000 to 2010 (Northeast: 28.0% to 46.9%; Midwest: 28.6% to 45.2%; South: 42.5% to 57.6%; West: 38.7% to 45.3%; all P for trend < .05; not shown).

Finally, we compared the observed number of male newborn circumcision events nationwide with the expected number that would have occurred had the distribution of male birth hospitalizations by insurance coverage type remained the same from 2001 to 2010, as had occurred in 2000 (Figure 3). We estimated that an additional 390 000 circumcisions might have occurred from 2001 to 2010 had the same proportion of birth hospitalizations remained covered by private health insurance throughout the 11-year observation period as in 2000.

FIGURE 3—

Increase in proportion of male newborn hospitalizations covered by Medicaid in relation to the observed and expected number of circumcision events nationwide: United States, 2000–2010.

DISCUSSION

Nationally, the proportion of newborns circumcised has fluctuated over the last 75 years. After reaching 80% following World War II and peaking during the 1960s, circumcision decreased to between 60% and 65% between the late 1970s and 1990s23 and was 65% in 1999.22 The most recent decrease observed in circumcision7,10 may have been influenced by changes in insurance coverage. While the number of births in the United States has decreased, the proportion covered by Medicaid has increased.27 Given that the decreasing trend in circumcision incidence nationwide was no longer significant once we accounted for insurance type, the decrease likely reflects the effects of temporal shifts in insurance coverage from the private to public sector, where circumcision incidence is lower,1,21 combined with decreases in state Medicaid coverage for circumcision services.28 To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth examination of how changes in health insurance coverage can affect trends in newborn circumcision.

Consistent with previous reports,9,21 differences in newborn circumcision incidence continue to exist by region and payer type. Our findings indicated that the same differences in circumcision observed by type of insurance coverage nationwide also exist within each region. Although circumcision incidence remained lowest in the West, the relative and absolute difference in incidence between hospitalizations with private versus Medicaid coverage was also highest in the West. It is worth noting that the West also has the largest number of states (currently 9 of 13) that no longer provide Medicaid coverage for circumcision, many of which ceased coverage before or around the release of AAP’s 1999 position statement.12

In addition, many Western states, particularly in the Southwest, have experienced disproportionately large increases in the proportion of infants born to Hispanic mothers compared with already significant increases reported nationwide.29 The fact that newborn circumcision tends to be lowest among Hispanics21,24,30 may further explain the consistently lower incidence observed in this region. As states in other regions evaluate Medicaid coverage for newborn circumcision and population demographics change,21 the marked differences in circumcision incidence observed by insurance type and lower circumcision incidence in the West might occur in other regions.

Recent analyses have suggested that the impact of statewide changes in Medicaid coverage on the incidence of circumcision might be substantial. An analysis from the 2004 NIS found hospitals in states with Medicaid coverage of circumcision had an incidence of circumcision 24 percentage points higher than hospitals in states without such coverage.21 In addition, even in states where newborn circumcision is covered by Medicaid, access to the procedure may be limited for Medicaid recipients who desire the procedure after their newborn has been discharged, unless medically indicated.

The decrease in circumcision incidence in the South—and then only among birth hospitalizations with Medicaid—warrants further discussion. Of note, 2 large Southern states (Florida and North Carolina) that participated in the NIS during the observation period discontinued statewide Medicaid coverage of circumcision after the release of AAP’s 1999 position statement. Although causality cannot be inferred, the timing of the changes in Medicaid coverage for these 2 states (July 2003 for Florida and December 2002 for North Carolina) corresponds closely with the largest 1-year decrease (7.6 percentage points; from 52.9% in 2002 to 45.3% in 2003) in circumcision incidence in the South among Medicaid-covered hospitalizations; conversely, there was only a minor, nonsignificant decrease of 1.5 percentage points among privately insured hospitalizations in the South (from 75.0% in 2002 to 73.5% in 2003). The NIS sampling design only recommends reporting estimates at the regional level, thus prohibiting direct examination of the effect of statewide cessation of Medicaid coverage on newborn circumcision trends in that state. Our initial examination of the related State Inpatient Databases from HCUP for Florida and North Carolina, however, indicate that discontinuing Medicaid coverage for circumcision resulted in an immediate 30% to 40% decrease in newborn circumcision incidence in those states.31 Thus, the impact of cessation of statewide Medicaid coverage on newborn circumcision rates for hospitalizations with public insurance may be significant.

Limitations

Our study was subject to some limitations. First, because our analysis excluded circumcisions beyond the inpatient newborn hospitalization (e.g., for religious or cultural reasons), and those conducted in outpatient settings for medical reasons, the incidence of newborn circumcision may be slightly higher. However, the nationwide incidence of circumcision during hospitalizations outside of the newborn period is estimated to be only 0.1%9; moreover, a follow-up study of males born in US army hospitals found that almost all circumcisions occurred during the newborn hospitalization.32 Second, incomplete data on key factors previously associated with circumcision (particularly race/ethnicity) could have affected our conclusions. Shifts in the distribution of newborns with regard to race/ethnicity toward groups with historically lower rates of circumcision (e.g., Hispanic infants) may have been partially responsible for the decreases observed in circumcision, rather than shifts in coverage from private insurance to Medicaid. Additional analyses that adjusted for race/ethnicity information that was available yielded similar statistical results and conclusions nationwide and for most regions; in the Midwest, however, where 52% of the data for race/ethnicity were missing, results differed statistically for deliveries covered by Medicaid (data not shown).

Our analysis also had strengths. First, we used a large nationwide sample of hospital inpatient care to provide updated regional and payer-specific trends in newborn circumcision incidence. Although all states do not participate in the NIS, estimates of circumcision incidence during birth hospitalizations from the NIS are comparable to those of the National Hospital Discharge Survey, which is conducted annually in all 50 states.7,10 Second, circumcision status was documented on newborn discharge records by hospital staff rather than parental report and is less prone to error.33

Conclusions

In summary, the incidence of newborn circumcision decreased from 2000 to 2010, particularly in the South among hospitalizations covered by Medicaid. This examination documented that this decrease coincides with the cessation of Medicaid coverage of circumcision in some states and a temporal shift in the proportion of births with private insurance (where incidence is generally higher) to public insurance (where incidence tends to be lower). A higher incidence of circumcision continues to exist among newborns with private insurance compared with Medicaid coverage, both nationally and regionally. Given that the new AAP recommendations recognize the health benefits of newborn circumcision yet current reimbursement policies prohibit equal access to the procedure,12,34 efforts should be made to reduce insurance barriers to newborn circumcision for families that desire the procedure.

Acknowledgments

This work was previously presented in part at the National HIV Prevention Conference; August 26, 2010; Atlanta, GA.

Human Participant Protection

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classified the project as research not involving human participants because the administrative data set does not include personally identifying information.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e756–e785. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobian AA, Gray RH. The medical benefits of male circumcision. JAMA. 2011;306(13):1479–1480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):585–586. [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Bcheraoui C, Zhang X, Cooper CS, Rose CE, Kilmarx PH, Chen RT. Rates of adverse events associated with male circumcision in US medical settings, 2001 to 2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(7):625–634. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 1999;103(3):686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Draft CDC recommendations for providers counseling male patients and parents regarding male circumcision and the prevention of HIV infection, STIs, and other health outcomes. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/MC-factsheet-508.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in in-hospital newborn male circumcision–United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(34):1167–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda J, Chari R, Elixhauser A. Circumcisions in US community hospitals, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #126. 2012. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb126.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015.

- 9.Nelson CP, Dunn R, Wan J, Wei JT. The increasing incidence of newborn circumcision: data from the nationwide inpatient sample. J Urol. 2005;173(3):978–981. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145758.80937.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owings M, Uddin S, Williams S. Trends in circumcision for male newborns in US hospitals. 1979-2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/circumcision_2013/circumcision_2013.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015.

- 11.American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP publications retired and reaffirmed. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):796. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark SJ, Kilmarx PH, Kretsinger K. Coverage of newborn and adult male circumcision varies among public and private US payers despite health benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(12):2355–2361. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Conference of State Legislatures. State health notes: circumcision and infection. 2006.

- 14.American Urological Association. Circumcision. 2007. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/about/policy-statements/circumcision.cfm. Accessed January 29, 2015.

- 15.Smith DK, Taylor A, Kilmarx PH et al. Male circumcision in the United States for the prevention of HIV infection and other adverse health outcomes: report from a CDC consultation. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(suppl 1):72–82. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Family Physicians Commission on Science. Position Paper on Neonatal Circumcision. Leawood, KS: American Academy of Family Physicians; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Medical Association. Report 10 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (I-99): Neonatal Circumcision. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1999. Council on Scientific Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiner C, Elixhauser A, Schnaier J. The healthcare cost and utilization project: an overview. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5(3):143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2009. 2011. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2009.jsp#Summary. Accessed January 29, 2015.

- 20.International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. DHHS publication PHS 80–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leibowitz AA, Desmond K, Belin T. Determinants and policy implications of male circumcision in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(1):138–145. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.134403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Discharge Survey. Estimated number of male newborn infants, and percent circumcised during birth hospitalization, by geographic region: United States, 1979–2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/9circumcision/2007circ9_regionracetrend.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015.

- 23.Sullivan PS, Kilmarx PH, Peterman TA et al. Male circumcision for prevention of HIV transmission: what the new data mean for HIV prevention in the United States. PLoS Med. 2007;4(7):e223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Introcaso CE, Xu F, Kilmarx PH, Zaidi A, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of circumcision among men and boys aged 14 to 59 years in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2005–2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(7):521–525. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000430797.56499.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowlessar NM, Jiang HJ, Steiner C. Hospital stays for newborns, 2011. HCUP statistical brief #163. 2013. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb163.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015. [PubMed]

- 28.Leibowitz AA, Desmond K. Infant male circumcision and future health disparities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(10):962–963. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: with special feature on socioeconomic status and health. 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus11.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015. [PubMed]

- 30.Castro JG, Jones DL, Lopez M, Barradas I, Weiss SM. Making the case for circumcision as a public health strategy: opening the dialogue. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(6):367–372. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cox SC, Whiteman M, Jamieson DJ, Posner SF, Barfield WD, Warner L. The effect of discontinuation of Medicaid coverage on the incidence of newborn circumcision. Paper presented at: Society for Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiologic Research Conference; June 27–29, 2012; Minneapolis, MN.

- 32.Wiswell TE, Tencer HL, Welch CA, Chamberlain JL. Circumcision in children beyond the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1993;92(6):791–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J et al. HIV and male circumcision—a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(3):165–173. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klausner JD. Newborn circumcision: ensuring universal access. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(7):526–527. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000431046.28649.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]