Abstract

Suicide is a global public health problem. Asia accounts for 60% of the world's suicides, so at least 60 million people are affected by suicide or attempted suicide in Asia each year. The burden of female suicidal behavior, in terms of total burden of morbidity and mortality combined, is more in women than in men. Women's greater vulnerability to suicidal behavior is likely to be due to gender related vulnerability to psychopathology and to psychosocial stressors. Suicide prevention programmes should incorporate woman specific strategies. More research on suicidal behavior in women particularly in developing countries is needed.

Keywords: Attempted suicide, domestic violence, suicide, women

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a global public health problem. Each year worldwide approximately one million individuals die by suicide, 10–20 million attempt suicide and 50–120 million are profoundly affected by the suicide or attempted suicide of a close relative or associate. Asia accounts for 60 percent of the world's suicides, so at least 60 million people are affected by suicide or attempted suicide in Asia each year.[1]

Global suicide rates is estimated to be 14/100,000 with 18/100,000 for males and 11/100,000 for females. Suicides represented 1.8% of the global burden of disease 1998 and is expected to increase to 2.4% in 2020.[2]

Men and women differ in their roles, responsibilities, status and power and these socially constructed differences interact with biological differences to contribute to differences in their suicidal behavior. More is known about differences in males and females in conditions like depression and schizophrenia than suicide.

Rates of suicide in most countries are higher in males than females. China is one important exception with higher rates in females, especially young women in rural China.[3] However, the last decade has seen a sharp decrease in suicide rate of rural women.

Suicide ranks as the number one cause of mortality in young girls between the ages 15 and 19 years globally.[4]

One of the most consistent findings in suicide research is that women make more suicide attempts than men, but men are more likely to die in their attempts than women. Despite this, remarkably few studies have focused upon suicidal behavior in women or attempted to explore the complex relationships between gender and suicidal behavior. One reason for the lack of investment in female suicidal behavior may be that there has been a tendency to view suicidal behavior in women as manipulative and nonserious (despite evidence of intent, lethality, and hospitalization), to describe their attempts as “unsuccessful,” “failed,” or attention-seeking, and generally to imply that women's suicidal behavior is inept or incompetent.[5,6]

The lack of investment in women's suicidal behavior may also arise from a global focus on the mortality of suicidal behavior (dominated by male deaths in all countries except China),[1,7] with this focus on suicide leading to a relative under regard for morbidity (in which women predominate). In most countries, men die by suicide at 2–4 times the rate of women, despite the fact that women make twice as many suicide attempts as men. However, while most countries collect and report national data for suicide, many countries neither record nor report national data for suicide attempts. Suicide data fails to fully represent the major female contribution to morbidity. If both mortality and morbidity are considered together then it is evident that the weight of disease burden in suicidal behavior is clearly female.[8]

SUICIDE RATE OF WOMEN

Suicide statistics was obtained from the mortality statistics of WHO's website and human development index (HDI), was used to categorize countries as low, medium, and high. For roughly half of the countries (53.1%) and one-third of the population (27.3%) there were no data on suicide. Country level suicide rates were aggregated to regional level by using a weighted average where the weights were proportional to the population of each country in the aggregated group.

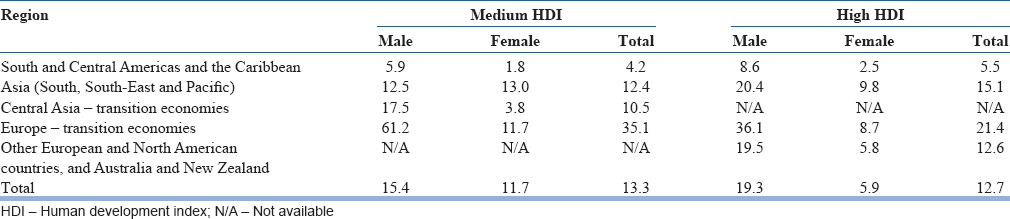

Table 1 provides a breakdown of male and female rates for medium and high HDI countries within each region. The difference between the average annual suicide rates for males and females in medium HDI countries (15.4/100,000 and 11.7/100,000, respectively, or a ratio of 2.0:1.5), was smaller than the comparable difference in high HDI countries (19.3/100,000 and 5.9/100,000 or a ratio of 2.0:6.0). This was largely accounted for by the difference between medium HDI and high HDI countries in Asia, where male and female suicide rates were approximately the same (12.5/100,000 and 13.0/100,000, respectively, or a ratio of 2.0:2.1). Table reveals that the highest suicide rate in women are found in Asia irrespective of their development status and so more Asian women commit suicide than women in any other region.[9]

Table 1.

Average annual suicide rates (per 100,000) in the 1990s, by region and HDI category

In India, the suicide rate of women is lower than that of men, but by a small margin and the male female ratio, which has been low at 1.4:1 has been gradually increasing and in the year 2013 the male:female ratio was 2:1. This gradual increase of the ratio denotes that less women are committing suicide in India.[10]

In a nationally representative survey in India, it was found that the overall age standardized suicide rates per 100,000 population at ages 15 years and elder were 26.3 for males and 17.5 for females. The age standardized rates at all ages were 18.6 for males and 12.7 for females.[11]

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS

Age

Suicide rates tend to increase with age. In 2000, the males rates for specific age category started at 1.4 (5–14 years) and gradually increased to 52.1 (75 years and older). The female rates for the different age groups are: 5–14 years - 0.4, 15–24 years - 4.8, 25–34 years - 6.2, 35–44 years - 7.8, 45–54 years - 9.7, 55–64 years - 10.6, 65–74 years - 12.3 and 75+ years - 15.9.[2]

In India, girls outnumber boys below 14 years and young women below 30 years are at a high risk of committing suicide.[12] Two large epidemiological verbal autopsy studies in rural Tamil Nadu reveal that at ages 15–24 years the female suicide rate was 109/100,000 and exceeded the male rate of 78/100,000[13] in one study and it was 162/100,000 in women and 96/100,000 in men in the other study.[14]

Patel et al.[11] also found that of the total suicides at ages 15 years and older, about 40% of male suicides (45/1000/114,800) and about 56% of female suicides (40 500/72,100) occurred at ages 15–29 years. Suicides occurred at younger ages in women (median age 25 years) than in men (median age 34 years). Male death rates at ages 15 and older were generally consistent at around 25–30/100,000 men across age groups. Female death rates peaked at about 25/100,000 women at ages 15–29 years, and then fell in older women.

At ages 15–29 years, suicide was the second leading cause of death in both genders, and accounted for nearly as many deaths as transport accidents in men and nearly as many as maternal deaths in women.

Marital status

In suicidology, one of the most commonly quoted observations is that being single (never married, separated, divorced, or widowed) acts as a risk factor for suicide.[15] Yet the evidence for this assertion comes primarily from developed countries, either via cross-sectional studies in which marital status-specific rates have been calculated in the general population[16] or case-control studies where marital status has been included as an exposure variable.[17] There is less evidence that marital status is a significant risk factor for suicide in studies conducted in developing countries. A large-scale case-control study in China, for example, found that single individuals were no more likely to suicide than married individuals.[18] Likewise, a review of available data in India concluded that marital status alone was not predictive of suicide, suggesting instead that family and social integration were more significant.[19] Ponnudurai and Jeyakar[20] also found that marriage was not a protective factor for women.

In general, marriage appears to be less protective against suicide for women than for men. This seems to be particularly the case for young women in developing countries in Asia. The life and marital circumstances of these women may make them vulnerable to suicidal behavior. Stresses may include arranged and early marriage, young motherhood, low social status, domestic violence, and economic dependence. Social, cultural, and religious constraints may discourage women from employment, careers, and financial and social independence, and encourage them to remain within unhappy marriages in dependent living arrangements with extended family.[21,22,23,24]

Methods

Men choose more lethal method to commit suicide than women.[25] Women tend to use self-poisoning for suicidal acts. In developed countries, it is over the counter medications which often have low lethality. However in rural Asia, women overdose with lethal pesticides and die. Gunnell et al.[26] state that 30% of suicides globally are by pesticide self-poisoning. Ajdacic-Gross et al.[4] studied methods of suicide derived from WHO mortality database for 56 countries and found differences between men and women with hanging and firearms used mostly by men and drowning or poisoning by women. In rural Latin American and Asian countries, poisoning with pesticide was a major problem among women. Choudhury et al.[27] found that 66.7% of females used pesticide for self-harm in Sunderbans, India. The use of lethal pesticides by young women in Asia in suicide attempts may result in higher suicide rate even if the intent was low.[18]

Self-immolation is one of the most common methods of suicide by women in India, Sri Lanka, Iran and other Middle-East countries. In Iran between 70% and 88% of self-immolation are by women.[28] In India 63% (n = 6292) of self-immolations were by women.[10] Self-immolation is the preferred method of suicide for women of Indian origin even after migrating to UK.

The Hindu concept of fire as a purifier, the practices of Sati and Jauhar, which were prevalent until two centuries ago and the easy accessibility and familiarity of kerosene at home are likely to be the reasons for the high prevalence of self-immolation in women.[29]

CLINICAL RISK FACTORS

The majority of clinical risk factors for suicide is similar in men and women. Although the prevalence of depression is high in women, more men die by suicide. Depression is the most common risk factor for serious suicidal behavior in both men and women and occurs twice as often in women as in men. The higher prevalence of depression in women appears related to an earlier age of first onset (rather than to persistence or recurrence of the disorder), with the gender difference first emerging in puberty and being paralleled by a similar gender difference in the emergence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt.[30]

Oquendo et al.[31] studied a cohort of 314 patients with Major depressive disorder (MDD) and found that the risk factors for men were a family history of suicide, comorbid substance abuse, and early separation. For women, the risk factors were a previous suicide attempt, the lethality of the attempt and lower number of reasons for living.

Eating disorders occur more often in women than men and are linked with suicidal behavior.[32] Women with anorexia are estimated to have a 50-fold increased risk of suicide, and suicide is the second leading cause of death in those with anorexia. Both bulimia and anorexia are linked with increased risk of suicide attempt, with suicide attempts reported in up to 20% of patients with anorexia and up to 35% of those with bulimia.[33] Women with borderline personality disorder have a higher prevalence of suicidal behavior.

Cougle et al.[34] studied suicidal ideation and attempt in a national household probability sample of 3085 women. The presence of only posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and a comorbid diagnosis of PTSD and MDD displayed the greater prevalence of suicide attempt than those with MDD only. They concluded that PTSD appears to be a particular strong predictor of suicide attempt.

In a cohort of 50,692 Norvegians, Bjerkeset et al.[35] found that suicide risk in comorbid anxiety and depression was 2-fold higher in men (odds ratio [OR] 7.4 confidence interval [CI] – 3.1–17.5) than women (OR 2.9 CI – 0.8–10.6). History of psychiatric admissions had a stronger impact on increasing suicide risk among females (OR 146 CI – 87.63–243.25) than males (OR 51.96 CI – 33.62–80.31).[36]

Kendal[37] studied 1.3 million cancer patients and found that 0.1% died by suicide. In men, head and neck and myelomas were associated with suicide, whereas suicide was lower in women at 0.02% and cervical cancer and metastasis were associated with suicide in women.

Menstrual cycle and pregnancy

The menstrual cycle is linked with nonfatal suicidal behavior, with suicide attempts occurring more often in those phases of the cycle when estrogen (and serotonin) levels are lowest.[38] This association is marked in women with premenstrual tension. Leenaars et al.[39] study revealed that 25% of women who had died by suicide were menstruating at that time compared to 4.5% of the control group.

Pregnancy usually has a protective effect against suicide, this protective effect during and after pregnancy may be reduced in mothers aged <20, in those pregnancies that end in stillbirth or miscarriage, and if the pregnancy is unwanted.[40,41,42]

In those with postpartum psychosis, suicide risk is increased 7-fold in the 1st year after childbirth and 17-fold in the longer term.[40,43]

For some young women, abortion is a traumatic life event that increases vulnerability to suicidal behavior. Rates of suicidal ideation and mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders are increased among women who have had induced abortions.[41,44,45]

An emerging issue is that women with fertility problems who were not able to conceive after treatment have a higher risk of suicide.

SOCIOCULTURAL FACTORS

Childhood adversities including physical, emotional and sexual abuse lead to substantially higher risk for suicide. Wife abuse is one of the most significant precipitants of female suicide. Research suggests that if a woman's support group does not defend her when she is the victim of violence that passes the bounds of normative behavior, her suicide may be revenge suicide, intended to force others to take vengeance on the abusive husband. Abused, shamed, and powerless wives take their own lives to shift the burden of humiliation from themselves to their tormentors. In Fiji, and South American societies, suicide associated with marital violence were also common. Data from a number of societies indicate that wife abuse remains one of the most important precipitants of female suicide and suicide attempts.[46] Domestic violence is a fairly common occurrence in most Asian societies and in the rural areas of many developing countries[47] and its practice is to a large extent socially and culturally condoned. A highly significant relationship between domestic violence and suicidal ideations has been found in many developing countries in population based samples. In Brazil 48% of women, Egypt 61%, India 64%, Indonesia 11%, and in Philippines 28% of women had significant correlation between domestic violence and suicidal ideation.[48] Unique cultural factors can also contribute to spousal abuse, in China for instance the government policy of a one child norm has led to enormous pressure on wives to give birth to the highly preferred male child. On failing which women especially in rural China are not infrequently mistreated, harassed, or divorced. The preference for the male child and the ill-treatment of the mother who gives birth to a female child is also seen in India. The prevalence of this desire for a male child is seen across the entire country as well as all sections of Indian society. Another distinctive form of abuse in Indian society is associated with dowry disputes. In India, dowries are a continuing series of gifts endowed before and after the marriage. When dowry expectations are not met, the young bride may be killed or compelled to commit suicide, most frequently by burning, suicide by burning amongst women is a major concern in India as it has become pervasive throughout all social strata and geographical areas. In a cohort of 152 burned wives, 32 (21%) were immolation suicides, and were associated with dowry disputes, these suicides occurred 2–5 years after marriage.[49] In a study conducted in a General Hospital in Durban significantly more married women than men cited marital violence, spousal alcohol abuse and spousal extramarital affairs as precipitants of their self-destructive behaviors.[50]

Gururaj et al.[51] found that domestic violence was found in 36% of suicides and was a major risk factor (OR 6.82 CI – 4.02–11.94) in Bengaluru, India.

Exposure to childhood sexual abuse is more common among females and increases vulnerability to subsequent psychopathology and to adverse life events, both associated with increased risk of suicidal behavior. The risk of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempt increases with the extent of sexual abuse.[52] Segal[53] found that sexual coercion and rape limits one's later reasons for not committing suicide.

Maselko and Patel[54] studied a population cohort (n = 2494) of women aged 18–50 years in Goa.

Experiencing hunger was associated with over 6-fold increase in the odds of attempting suicide. Young age at marriage increased the risk 6-fold while exposure to violence was associated in a 7-fold increase. There is evidence of an association between female suicidal behavior and childlessness in developing countries.[55,56]

Several studies have reported a 2–3-fold increased risk of suicide among women with cosmetic silicone gel-filled breast implants.[57]

Global evidence challenges widespread assumption about women and suicidal behavior. One such assumption is based on Durkheim's theory that women are immune from suicide as long as they remain “feminine,” family bound and socially subordinate. There is evidence contrary to this theory, actually social equality protect women from suicide, especially among the young. A recent study of 33 developing and industrialized countries found that women suicide rates were lower in countries with social structures emphasizing social equality.[58]

PROTECTIVE FACTORS

Pregnancy usually protects against suicide. Suicide rates in pregnancy are estimated to be up to half those of women who are not pregnant.[40,44] Motherhood, especially when children are very young and most dependent, also protects against suicide.[40,41,59] Qin et al.[36] found that having a child <2-year-old significantly decreased suicide (OR 0.26 [0.08–0.85]) risk for women.

Women may also be protected against suicide because they are more willing to ask for, and more likely to be offered, help for emotional problems. They may more often have family support, social networks, good social skills, and be more likely to use telephone help lines, visit family doctors, discuss their problems with others, and have better opportunities to access social and health services. Because women tend to have better verbal and social skills than men, they may respond better than men to psychological and cognitive-behavioral therapies for depression.[60]

Further, the choice of less lethal means to suicide increases their chance of survival.

SUICIDE PREVENTION IN WOMEN

The main obstacle to the prevention of suicidal behavior in women is the belief that suicide is a male problem and an over emphasis on individual factors and the under appreciation of social, economic and cultural factors in female suicidal behavior.[61] It is further compounded by the fact that there is lack of women specific research on suicide. Significant progress in the prevention of female suicidal behavior may require a paradigm shift of focus to ecological factors in addition to individual factors. Education, economic security and empowerment of women should be an integral part of suicide prevention strategy. Strict enforcement of the prohibition of forced marriages, dowry and child marriage in countries where they are prevalent is important. Reduction of intimate partner violence will reduce suicidality in women. In the absence of sexual abuse, the female suicide attempt over lifetime would fall by 28% relative to 7% in men.[62] Additional strategies would be to reduce media portrayal of women dying by suicide due to interpersonal conflicts and to enhance women's ability to cope with interpersonal and intergenerational conflicts.

CONCLUSION

Women are more likely than men to report suicidal ideation and attempts and to be hospitalized for suicide attempts and hence in terms of total burden of morbidity and mortality combined the burden of female suicidal behavior is more than men.

Women's greater vulnerability to suicidal behavior is likely to be due to gender-related vulnerability to psychopathology and to psychosocial stressors. There is an urgent need for more research on suicidal behavior in women, particularly in developing countries.

Suicide prevention programs should incorporate woman specific strategies. Reducing suicidal behavior in women should be a public and social objective rather than a traditional exercise in the mental health sector.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: The author is Founder Trustee of SNEHA, an NGO working in suicide prevention in Chennai. Her work as a trustee is honorary and she does not receive any remuneration from the NGO.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beautrais AL. Suicide in Asia. Crisis. 2006;27:55–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.2.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. A global perspective on the magnitude of suicide mortality. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford Text Book of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 91–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng AT, Lee CS. Suicide in Asia and far east. In: Hawton K, Van Heeringen K, editors. The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Chichestor, UK: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. pp. 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajdacic-Gross V, Weiss MG, Ring M, Hepp U, Bopp M, Gutzwiller F, et al. Methods of suicide: International suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:726–32. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canetto SS, Lester D. The epidemiology of women's suicidal behavior. In: Canetto SS, Lester D, editors. Women and Suicidal Behaviour. New York: Springer Publication; 1995. pp. 35–57.10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy GE. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:165–75. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yip PS, Liu KY. The ecological fallacy and the gender ratio of suicide in China. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:465–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beautrais AL. Women and suicidal behavior. Crisis. 2006;27:153–6. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.4.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayakumar L, Nagaraj K, Pirkis J, Whiteford H. Suicide in developing countries (1): Frequency, distribution, and association with socioeconomic indicators. Crisis. 2005;26:104–11. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.3.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New Delhi, India: National Crime Records Bureau; 2013. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, Ramasundarahettige C, Vijayakumar L, Thakur JS, Gajalakshmi V, Gururaj G, et al. Suicide mortality in India: A nationally representative survey. Lancet. 2012;379:2343–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer P, Ziaian T. Suicide, gender, and age variations in India. Are women in indian society protected from suicide? Crisis. 2002;23:98–103. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.23.3.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R. Suicide rates in rural Tamil Nadu, South India: Verbal autopsy of 39 000 deaths in 1997-98. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:203–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil JP, George K, Prasad J, Minz S, et al. Evaluation of suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies, 1994-9. BMJ. 2003;326:1121–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis AT, Schrueder C. The prediction of suicide. Med J Aust. 1990;153:552–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JC, Mercy JA, Conn JM. Marital status and the risk of suicide. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:78–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Erikson T, Qin P, Westergaard-Nielsen N. Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Lancet. 2000;355:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: A national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002;360:1728–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao AV. Suicide in the elderly: A report from India. Crisis. 1991;12:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponnudurai R, Jeyakar J. Suicide in madras. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:203–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan MM, Reza H. Gender differences in nonfatal suicidal behavior in Pakistan: Significance of sociocultural factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998;28:62–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhugra D. Sati: A type of nonpsychiatric suicide. Crisis. 2005;26:73–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MM. Suicide prevention and developing countries. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:459–63. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.10.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vijayakumar L, John S, Pirkis J, Whiteford H. Suicide in developing countries (2): Risk factors. Crisis. 2005;26:112–9. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.3.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denning DG, Conwell Y, King D, Cox C. Method choice, intent, and gender in completed suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30:282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, Konradsen F. The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: Systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhury AN, Banerjee S, Das S, Sorkar P, Chatterjee D, Mondal AD. Household survey of suicidal behavior in a coastal village of Sundarban region, India. Int Med J. 2005;12:275–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmadi A, Mohammadi R, Schwebel DC, Yeganeh N, Soroush A, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Familial risk factors for self-immolation: A case-control study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1025–31. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijayakumar L. Hindu religion and suicide in India. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford Text Book of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Med. 2000;30:23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oquendo MA, Bongiovi-Garcia ME, Galfalvy H, Goldberg PH, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, et al. Sex differences in clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression: A prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:134–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franko DL, Keel PK. Suicidality in eating disorders: Occurrence, correlates, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:769–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Joyce PR. Temperament, character and suicide attempts in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and major depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cougle JR, Resnick H, Kilpatrick DG. PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in relation to suicidality: Cross-sectional and prospective analyses of a national probability sample of women. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:1151–7. doi: 10.1002/da.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjerkeset O, Romundstad P, Gunnell D. Gender differences in the association of mixed anxiety and depression with suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:474–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergård-Nielsen N, Eriksson T, Mortensen PB. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kendal WS. Suicide and cancer: A gender-comparative study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:381–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders KE, Hawton K. Suicidal behaviour and the menstrual cycle. Psychol Med. 2006;36:901–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leenaars AA, Dogra TD, Girdhar S, Dattagupta S, Leenaars L. Menstruation and suicide: A histopathological study. Crisis. 2009;30:202–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.30.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ. 1991;302:137–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6769.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gissler HE, Lonnqvist J. Suicides after pregnancy in Finland, 1987-1994: Register linkage study. Br Med J Clin Res. 1996;313:1431–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7070.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaiva G, Tiessier E, Cottencin O, Goudemand M. On suicide and attempted suicide in pregnancy. Crisis. 1997;18:20–7. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.20.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Faragher EB. Suicide and other causes of mortality after post-partum psychiatric admission. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:209–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Abortion in young women and subsequent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Counts DA. Female suicide and wife abuse: A cross-cultural perspective. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1987;17:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1987.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heise LL, Raikes A, Watts CH, Zwi AB. Violence against women: A neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:1165–79. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geneva, Switzerland: The World Health Organization; 2001. World Health Report; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar V. Burnt wives – A study of suicides. Burns. 2003;29:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pillay AL, van der Veen MB, Wassenaar DR. Non-fatal suicidal behaviour in women – The role of spousal substance abuse and marital violence. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:429–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Subbakrishna DK, Ranjani R. Risk factors for completed suicides: A case-control study from Bangalore, India. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11:183–91. doi: 10.1080/156609704/233/289706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fergusson DM, Mullen PE. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. Childhood Sexual Abuse – An Evidence Based Perspective; pp. 91–4. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Segal DL. Self-reported history of sexual coercion and rape negatively impacts resilience to suicide among women students. Death Stud. 2009;33:848–55. doi: 10.1080/07481180903142720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maselko J, Patel V. Why women attempt suicide: The role of mental illness and social disadvantage in a community cohort study in India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:817–22. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Batra AK. Burn mortality: Recent trends and sociocultural determinants in rural India. Burns. 2003;29:270–5. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fido A, Zahid MA. Coping with infertility among Kuwaiti women: Cultural perspectives. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50:294–300. doi: 10.1177/0020764004050334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Villeneuve PJ, Holowaty EJ, Brisson J, Xie L, Ugnat AM, Latulippe L, et al. Mortality among Canadian women with cosmetic breast implants. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:334–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webster Rudmin F, Ferrada-Noli M, Skolbekken JA. Questions of culture, age and gender in the epidemiology of suicide. Scand J Psychol. 2003;44:373–81. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qin P, Mortensen PB. The impact of parental status on the risk of completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:797–802. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hawton K. Sex and suicide. Gender differences in suicidal behaviour. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:484–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Canetto SS. Prevention of suicidal behavior in females: Opportunities and obstacles. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention: A global perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 241–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bebbington PE, Cooper C, Minot S, Brugha TS, Jenkins R, Meltzer H, et al. Suicide attempts, gender, and sexual abuse: Data from the 2000 British psychiatric morbidity survey. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1135–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]