Abstract

Alcohol and substance use, until recently, were believed to be a predominantly male phenomenon. Only in the last few decades, attention has shifted to female drug use and its repercussions in women. As the numbers of female drug users continue to rise, studies attempt to understand gender-specific etiological factors, phenomenology, course and outcome, and issues related to treatment with the aim to develop more effective treatment programs. Research has primarily focused on alcohol and tobacco in women, and most of the literature is from the Western countries with data from developing countries like India being sparse. This review highlights the issues pertinent to alcohol and substance use in women with a special focus to the situation in India.

Keywords: Alcohol, addiction, drug abuse, gender, substance use disorders, women

INTRODUCTION

Psychoactive substance use, until recently, has largely been perceived as a male problem and research, as a result, has been largely androcentric and insensitive to gender variations. Historically, women using substance have always been frowned upon. Rules on acceptability dates back as far as laws of Hammurabi[1] in the west and the Manusmriti in India which states that, “a wife who drinks wine … may be abandoned at any time.”[2] Only around the mid 1970s, partly prompted by the then ongoing women's liberation movement, institutes like the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism started making efforts to garner scientific and public attention on gender issues.[3] Subsequently, with the feminization of HIV epidemic and the obvious role of drug use in catalyzing its spread, focus on women and substance use became necessary.

Worldwide, alcohol use in women has received the widest attention. While problems related to illicit substance use and their treatment mirror the issues related to alcohol use in many ways, important differences also do exist, warranting need for independent research. The singular theme that cuts across any substance use in women in any country, however, is the intense stigma suffered by these women, which acts as a significant barrier to treatment and encourages the victimization of drug using women.[2] This review attempts to highlight such problems unique to substance using women, as knowledge of such issues is necessary for developing effective services and planning appropriate interventions.[4]

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Gender differences in substance use have been consistently observed in the west, in general population as well as in the treatment-seeking samples, with men exhibiting significantly higher rates of substance use, abuse, and dependence.[5,6] The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; n = 43,093) conducted in the US reported that men were 2.2 times more likely than women to have abused various substances and 1.9 times more likely to have substance dependence.[6] Data from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) in 2000 from US similarly showed that 5% of women, as compared to 7.7% men, presently used illicit substances. However, studies suggest that in the last couple of decades, this gender gap has narrowed.[7] Compared to the surveys of 1980s that reported 5:1 male/female ratio of alcohol-use disorders,[8] the ratio dropped to approximately 3:1 in a 2007 survey.[9] Further, in a recent 2012 study amongst 41.5 million illicit drug users, more than 42% were women, suggesting a male/female ratio of 1.4:1 at the present time.[10] In case of prescription drug abuse, several studies actually report their use to be higher in women than men, particularly for narcotic analgesics and tranquilizers.[11] Other alarming features brought to light by the NHSDA include the fact that rates of substance use were almost similar between girls and boys in the age groups of 12–17 years (9.5% vs. 9.8%) and tobacco use was higher in these adolescent girls (14.1% vs. 12.8%, respectively). While drug abuse significantly decreased as boys grew older (year-over-year reduction), the same was not seen in girls.[12]

The relative proportion of various drugs used by females varies from region to region. In “wet” culture countries like the US, alcohol use by women has more social acceptance, but for other drugs women have always represented a minority.[13] In “dry” culture country like India, rates consumption of alcohol is far less as compared to the west. The GENECIS study reported that 5.9% of females consumed alcohol at least once in the past year, as compared to 32.7% of men.[14] Direct comparison of most other drug use is not possible as no national level survey on substance abuse in women has been conducted in our country. The earliest national studies dating back to 1980s report negligible drug use rates among women with alcohol use in 3.2%, and barbiturates, cannabis, heroin, pethidine, morphine use in as low as 0.1–0.3% of women.[15,16,17] Four large epidemiological studies in the early 1990s, with sample sizes varying from 4000 to 30,000, revealed that 6–8% of women had ever used drugs in their lifetime.[15,18,19,20] North-Eastern States were an exception even then, where heroin use in women was found to be high at 14%.[20] With the NDPS (Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances) act criminalizing traditional opium and surge of smuggled heroin from Afghanistan, the 1990s also witnessed an increase in use of heroin among women. Multiple studies document increased heroin use in large cities like Mumbai,[21] Kolkota,[22] and Delhi,[23] during this time.

The only national epidemiological surveys of the country: “National Survey on Extent, Pattern and Trends of Drug Abuse in India” of 2001; sadly focused only on males. An exploratory “Rapid assessment survey (RAS study)” component of the same survey which used nonrandom sampling to collect information on drug-use from 14 cities of India and found that around 7.9% of women across cities used at least one type of substance. Heroin, alcohol, cannabis, and pain-killers were the dominant substances of abuse. Another component of the national survey, called “Focused thematic study on drug abuse among women (Women's study)” using snowballing sampling technique, interviewed 75 women substance users from Mumbai, Delhi, and Aizawl. The women's study is significant as it reported high rates of opioid and alcohol use in women substance users with an alarming 40% women reporting lifetime history of Injection drug use.[24]

A recent study focusing exclusively on substance using women which merit mention is the substance, women, and high-risk assessment study. The survey focused specifically on women in 110 Non-Governmental Organizations across the country,[25] and interviewed more than 6000 women which included both female substance users (FSUs) as well as female partners of male substance users. The study reported high rates of alcohol, cannabis, opioids, injection use as well as the use of solvents, which was hitherto unreported in Indian women. In addition, mean age of initiation for solvent use was found to precede even that of nicotine (16.5 vs. 18.4 years), thereby becoming the “gateway drug” in many cases.

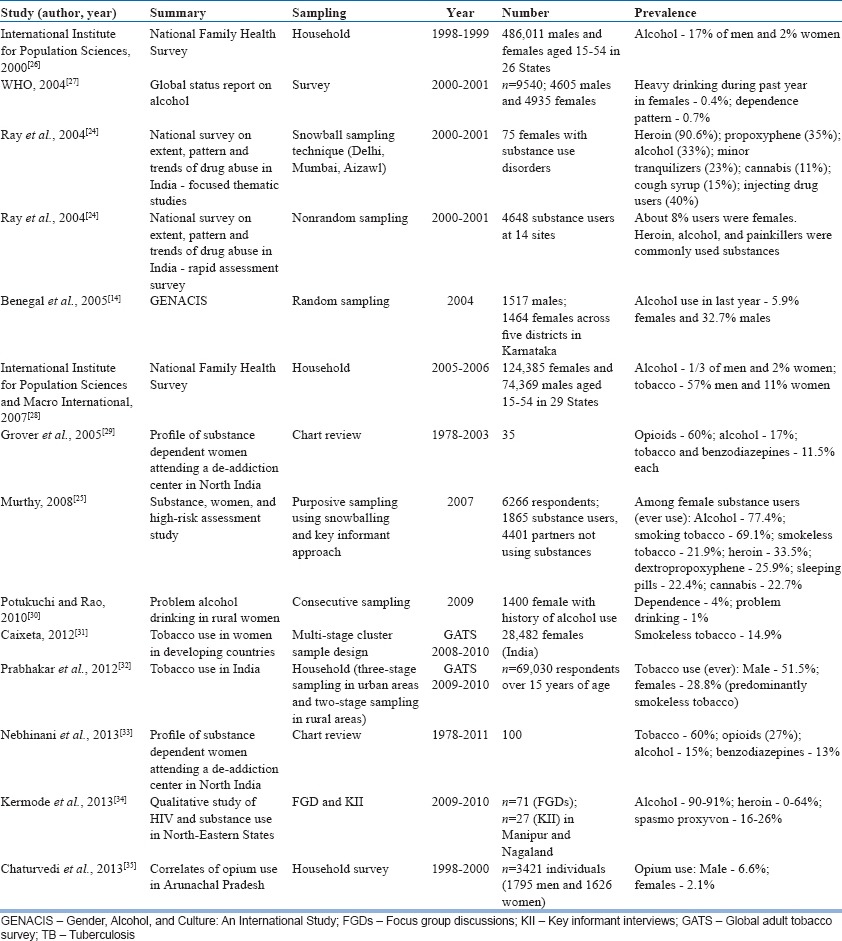

In addition to these large-scale studies, several smaller reports look into various aspects of drug using females in India, which are detailed in Table 1. Data from the addiction treatment centers also report an increase in the number of women seeking treatment, which parallels the national trends in terms of high number of opioid users followed by alcohol and tobacco.[29,33]

Table 1.

Indian studies on substance use prevalence and patterns in past decade

Table 1 presents the studies on substance use in women in past decade.

RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH SUBSTANCE USE

Biological factors

Gender differences in neuroendocrine adaptations to stress and reward systems are known to mediate women's susceptibility to both substance use patterns as well as relapses.[36] Studies have reported that, among women substance-users, attenuated neuroendocrine stress response (that is, blunted adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol) is found following exposure to stress and drug cues and this hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical dysregulation in females may be a key to enhanced vulnerability to relapse in response to negative affect.[37,38]

In terms of gender differences in the physiological effects, alcohol has been the most widely studied substance. The ovarian steroid hormones (e.g., estrogen, progesterone), metabolites of progesterone, and negative allosteric modulators of the γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor like dehydroepiandrostenedione are found to influence the behavioral effects of substances.[39,40] As compared to men, women are known to become intoxicated after consuming smaller quantities of alcohol indicating that women achieve higher blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) after consumption of the equivalent amount of alcohol. This may be due to less body water in comparison to size. In addition, lower levels of alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes in the stomach result in a higher amount of alcohol in the systemic circulation. Low antidiuretic hormone effect is reported to be more prominent with beverages of higher alcohol content,[41] so that among chronic alcoholic women virtually all the alcohol consumed tends to get absorbed. However, these gender difference tends to disappear in females older than 50 years.[42] Additionally, unlike the predictable and reproducible peak BACs in men, unpredictable day-to-day variability with higher peaks in the premenstrual phase has been observed in women.[43] Interestingly, women meeting the diagnostic criteria for the premenstrual syndrome are found to drink more heavily than controls and have higher rates of abuse and dependence.[44] Conversely, increased alcohol consumption during the premenstrual phase is associated with higher premenstrual symptomatology.[45]

Research is sparse for the biological difference in response in women for other addictive substances and is often limited to animal studies. For nicotine, even though women smoke similar numbers of cigarettes daily, heavy smokers exhibit lower nicotine plasma levels and also show greater exposure to smoke reflecting the need for more and larger puffs to achieve the same nicotine intake. This may be implicated in observed gender differences of smoking-related medical consequences.[46] Like alcohol, studies on female nicotine users showed a potential greater saliency in the luteal phase of the cycle.[40,47]

In animal studies, researchers have found sex-related differences of cannabis on corticotropin-releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin gene expression in the hypothalamus in female rats.[48] Whether or not these differences also exist in humans is as yet unknown. With opiates, women report higher rates of nausea and analgesia than do men,[49] and it is suggested that the interaction between opiate receptors and sexual hormone receptors may be implicated in gender differences observed in the magnitude and potency of opiate response.

Genetic and environmental factors

Irrespective of gender, twin and adoption studies suggest robust role of genetic factors in the causation of addiction. However, genetic influences seem to be greater for men (heritability of 33% for men and 11% for women).[50,51] In women, initiation of illicit substances is found to be shaped more by environmental factors, whereas progression to abuse or dependence is determined by genetic influences.[52,53] Across cultures, the most important environmental factor that influenced drinking in women was found to be alcohol use or abuse by spouse or another close family member and either the women was coerced into drinking or started using alcohol to give company to their partners.[25,54,55] In the Women's study from the National Survey, the primary reasons reported by the women for initiating substance use were influence of friends (48%), stress and tension (16%), and influence of spouse or partner (11%).[24] Apart from a substance using family member or friend, having specific vulnerability such as transition and lifestyle changes increasing the risk of drug abuse in women have also been reported in various studies.[29,33,55] The evidence implies the important role of environmental influences in association with genetic factors in the development of drug abuse in females.

Psychological factors and psychiatric comorbidities

Co-morbid psychological factors have been strongly implicated in women with substance use disorders irrespective of the type of substance used.[56,57] History of early traumatic life events may precipitate the development of substance-use disorders in later life and studies report the lifetime prevalence of substance use to be 4 times higher in women with a history of sexual assault.[58] A population-based study in 1411 adult female twins reported a relationship between the severity of self-reported childhood sexual abuse and risk for developing drug dependence with those reporting genital intercourse comprising the highest risk group.[59] A more recent study of women who had experienced sexual assault as an adult (n = 1863) reported substance as a coping strategy for the resultant posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[60] Significant association between substance use and major depression in women has also been reported,[61] with studies suggesting an odds ratio for developing alcohol abuse or dependence of 4.1 for females as compared to 2.67 for males with major depression. Rates of suicide attempts are also significantly higher in drug-dependent women.[62] The national survey on drug use and health (n = 133,221 adults) reported that though both genders were likely to have higher prevalence of anxiety disorder, only drug using women were more likely to have major depressive disorder as compared to men.[63] Secondary analysis of the NESARC revealed that drug using women were more likely to have mood and anxiety disorders; were at a greater risk for developing externalizing disorder and also experienced “telescoping” effects.[64,65] Eating disorders are also commonly found in women with substance use disorders.[66] A review of clinical populations reported that about 40% women reported comorbid lifetime eating disorders.[67] Among women with bulimia or binge-eating disorders, rates of substance use were higher in those with a history of physical or sexual abuse.[68]

Indian studies on treatment-seeking women users have found similar results with co-morbid depressive disorders in 12%, adjustment disorder in 5%, somatoform disorder in 3%, anxiety disorder in 2%, schizophrenia in 2%, obsessive compulsive disorder in 1% and bipolar affective disorder in 1%.[33] Similarly, from the national survey, the RAS respondents reported several psychological problems like insomnia, depression, anxiety, suicidal attempts and guilt feelings.[24]

Sociocultural factors

Social perception of women who use alcohol can be understood within the context of the relational model.[69] Society expects a woman to a wife, a mother, caretaker, sexual partner, and nurturer, and when she deviates from these prescribed roles, she tends to face stigma and discrimination. Thus, alcohol use in women is linked with sexual misconduct, promiscuity, and neglect of children and significant others, a set of conditions that cause stigma and social discrimination.[70] Early initiation into sex and forced or coercive sex to support drug use habit, also puts them at conflict with law resulting in harassment by both hardened criminals as well as police.[24]

In contrast to males, where substance use may affect occupation, women report more problems in family and social domains. FSUs are more likely to get separated or divorced than their male counterparts. Key informant interviews in the women's study of the national survey revealed that 31% of the women across the sites were single, and 32% were separated or divorced. FSUs in the RAS study were also mostly single and reported an early onset of substance use as well as high levels of alcohol and substance use in their families. The family attitude was generally harsh or indifferent to them, and domestic violence was frequently reported. Moreover, factors like poor education status, lack of job, young age at work, early marriage, and lack of social support increased vulnerability of such females.[24]

INITIATION AND COURSE OF SUBSTANCE USE IN WOMEN

Initiation of alcohol and substance use

The reasons for initiation of substance use among adolescent girls have been studied predominantly in Western cultures. Commonly cited reasons for initiation include adolescent depression, problems in adjustment, hanging out with older male friends, peer pressure, feeling of a sense of glamor and power, and disappearing stereotypes about femininity.[55] Research suggests that, while many of these reasons may be gender neutral, some factors like puberty may affect girls more than boys. A study on Latino females aged 14–24 years (n = 1411) receiving services from family planning clinic in California reported that cultural factors like nontraditional families and acculturation influenced initiation to tobacco use.[71] Another study, which determined critical incidents that contributed to initiation of substance use among women, reported family factors, social/environmental factors, life stresses, relationship issues, abuse, and peer pressure as contributory.[72]

Indian studies report elder males (friend, family member or spouse) as a common initiating agent.[33,35] Certain occupations such as sex work and working in alcohol joints, also served as risk factors for initiation of alcohol or substance use.[34,73] Curiosity and alleviation of stress or physical pains also emerged as important factors in some studies.[29,33] Positive expectancies regarding benefits of alcohol use like alleviation of depressed mood have also been cited. Older women were found to initiate alcohol as it was believed to have major restorative properties after childbirth.[55]

Course of alcohol and substance use

Unlike men, women seem to progress faster between landmarks associated with the developmental course of alcoholism (e.g., regular drinking or loss of control) and tend to experience greater medical, physiological and psychological impairment earlier in their drinking career. This accelerated progression of alcoholism in women is commonly referred to as “telescoping”[74,75] and is consistently observed in studies investigating gender and substance-use disorders. Thus, it has been observed that when women enter substance abuse treatment, they typically present with a more severe clinical profile than men, despite lesser frequency as well as the quantity of alcohol use.[76] Similar evidence have been reported for other substances like tobacco, opioids, and cocaine.[77,78] Studies have reported that, as compared to men, women use smaller amounts of heroin, use it for shorter periods of time, and are more likely to inhale it.[66,79] For cannabis, no gender differences in patterns of use were found in a large Australian survey of adolescents.[80] However, others report that as compared to men, women are initiate cannabis later[81] and use it occasionally.[82]

CONSEQUENCES OF ALCOHOL AND SUBSTANCE USE IN WOMEN

Health consequences

Women tend to develop alcohol liver disease with comparatively shorter duration and less amount of alcohol consumption than men; more women die from cirrhosis than men. Heavy alcohol consumption may also be associated with increased risk of menstrual disturbances, infertility and breast cancer. In women, alcohol intake is also found to be associated with higher risk for hypertension, overall cardiovascular mortality,[83] and subarachnoid hemorrhage,[84] an effect that seems to be related to lower levels of serum ionized magnesium.[85] Prolonged heavy drinking is also known to be an etiologic factor in many diseases of the gastrointestinal, neuromuscular, cardiovascular, and other body systems,[86] which women may develop more rapidly than men.

Similar findings have been reported in the Indian studies wherein women drug users were found to develop more severe pneumonia, rupture of lungs and tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis, HIV, and other adverse effects of AIDS.[87] Both the RAS and the women's study in the National Survey found several physical complications like sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), abscess, TB, irregular menstrual cycles, amenorrhea, and medical termination of pregnancy.[24]

The role of alcohol and substance use disorders in the spread of STDs has been highlighted by the AIDS epidemic. Alcohol consumption in heterosexual women was associated with less condom use and other high-risk sexual behaviors, posing additional risk of getting infected.[88] In Indian studies too, women drug users are reported to engage in unsafe practices more frequently. Moreover, while many women indulge in sex to sustain their alcohol and drug use habits, studies from sex-workers report that many of the female sex workers use alcohol and substances before sexual activity.[34,89]

Legal consequences

Although, as compared to males, criminal activity is less observed in substance using females, existing data indicate that dependency on drugs and increased vulnerability makes women more prone to participate in drug-related crimes. In the RAS component of National Survey, India, 7–20% of women substance users reported several legal problems due to drug abuse viz., being in a police lock up or prison. Almost 44% of the women in the women's study reported a history of incarcerations due to their peddling activities, sex work, pick-pocketing and theft charges.[24] These issues from the Indian studies reflect a global truth of more victimization of female drug users.

Social and familial consequences

As compared to men, women generally face poorer social support.[54] Social consequences of alcohol and substance use can range from interpersonal difficulties to homelessness, unemployment, poverty, and a general disengagement from the communities.[90] Women's study of the National Survey found that not only many FSUs were separated or divorced, but they also faced harsher treatment from family and were at increased risks for physical and verbal abuse.[24] Similar results have also been noted in women seeking treatment for de-addiction.[29,33]

TREATMENT PROCESS

The treatment process can be understood at three different levels: (1) Treatment entry and treatment seeking, (2) retention, and (3) treatment outcome.

Treatment entry and treatment-seeking

Western studies indicate that relatively low proportion of women enter substance abuse treatment programs.[91,92] The ratio of treatment seeking men to women was found to be 3.3:1 in alcohol treatment facilities while, for that time-period, the male/female ratio of alcohol use disorders in the population was estimated to be 2.7:1.[93,94] Similarly, the Australian National Household Survey showed a 2:1 ratio of high-risk drinking in males and females in the general population, but estimates of ratios of men to women in alcohol treatment services were found to range from 3:1 to 10:1.[95]

No gender differences were found in studies which looked at short time periods following disease onset (for example, 1–8 years), or those using broad definitions of treatment-entry (for example, ever consulting a professional).[96,97,98] Surveys that examined a longer period (>8 years) demonstrated a lower lifetime probability of women ever entering treatment for alcohol use disorders as compared to men.[93]

In India, data from treatment centers of Delhi, Jodhpur and Lucknow between 1989 and 1991 found 1–3% of treatment seekers to be female. Similarly, the Drug Abuse Monitoring System reports about 2.3–3% of new treatment seekers to be women.[24,99]

A retrospective analysis of all substance use cases registered in the de-addiction center at Chandigarh between 1978 and 2008 revealed that out of 6608 only 0.5% were females.[100]

Certain systemic, physical, social, and personal barriers are considered responsible for low rates of treatment-seeking among women.[101] Systemic Barriers include: Lack of decision making power in women, limited knowledge among the professionals due to lack of proper studies; lack of appropriate gender-specific treatment models; lack of appropriate treatment models to address co-morbid psychiatric disorders. Physical or structural barriers include: Lack of services for pregnant women; location and cost of treatment; rigid program schedules; lack of provision for female inpatient ward; lack of physical safety at treatment centers; fear of losing custody of children, fear of prosecution; lack of childcare outside of treatment or provided as part of treatment services. Social cultural and personal barriers include: Disadvantaged life circumstances; stigma, shame and guilt; lack of support from family; responsibilities at home; decreased perception of need for treatment and less education about treatment as a viable option.[98,102,103,104,105,106] Perhaps, stigma is the most important barrier to treatment-seeking, which is further compounded by a lack of gender focus in the substance abuse treatment delivery models, the staff not being trained in gender sensitive issues, a lack of resources for women and negative attitudes toward women drug users.[103,107] However, it has also been reported that once women enter treatment, no gender differences are observed.[107]

Treatment retention

In general, longer treatment episodes and successful completion of treatment are related to positive outcomes. However, as many as 50% of patients in substance use treatment programs tend to drop out within the 1st month of treatment. Studies that have examined gender differences in substance abuse treatment retention and completion show inconsistent results. A longitudinal study (1996–1999) conducted in both public and private substance abuse treatment facilities (The Alcohol and Drug Service Study (ADSS)) in US, included data from 4689 individuals (including 1239 women) and found that after controlling for client and facility characteristics, gender was not associated with completion of planned treatment. Rather, factors like education level, primary source of referral for treatment, primary expected source of payment for treatment, and type of facility were associated more with treatment completion.[108]

A retrospective chart-review of individuals (1804 men and 667 women) seeking public-funded substance abuse treatment in Detroit found that female patients had significantly lower retention as well as treatment-completion rates, than male patients, even after controlling for problem severity, primary drug of abuse, and referred treatment setting.[109] In contrast a Los Angeles County study (n = 511) reported that female patients completed more months of formal treatment programs, as compared to men, and no gender-difference were found in 12-step self-help program participation duration.[110]

Over the years, studies have also attempted to look into certain characteristics that that may be associated with treatment retention and completion, specifically for each gender and those that may be applicable to both. Gender-neutral factors like having good financial resources and having fewer mental health problems,[111] having less-severe substance use problems,[112] being employed,[113] older age,[114] and referral from criminal justice system[112] results in better outcome. In women, treatment completion was predicted by legal or agency referral and higher income; failure to complete treatment was predicted in women by more severe substance dependence and higher employment scores.[111] Studies using women-only samples have reported associations between psychological function, personal stability and social support, levels of anger, treatment beliefs, and referral source with the rates of treatment-retention and completion.[111] On similar lines, Kelly et al. reported that among women attending a women-centered program, factors such as having fewer children, higher levels of personal stability, less involvement with child, protective services, and fewer family problems predicted higher treatment completion.[115]

Apart from individual characteristics, treatment-characteristics are also associated with retention rates among women. The Alcohol and Drug Service Study reported that women-only facilities or those with childcare services did not affect treatment completion, though it did influence length of stay. Completion was improved by programs providing nonhospital residential facility or those providing combined treatment for mental health and substance abuse.[108] In contrast, a review of 38 studies concluded that women have the best response when they attend women-only programs rather than mixed-gender programs.[116] A flexible philosophy, friendly staff, women only space, home visits, and childcare are the factors that have been found to ensure treatment continuation in studies from the developed world. Networking to handle issues like HIV and pregnancy, focus on empowerment (educational, vocational, life-skills) and addressing policies or laws discriminatory to women needs to be implemented.[25]

Treatment outcome

There is little research to indicate the best way to treat substance use in women. Though, there are concerns regarding the effectiveness of substance abuse treatment for women,[117,118] various studies have found few or no gender differences in treatment outcome across various populations.[107] In a study by Hser et al., no overall gender differences was found in 1-year drug and alcohol treatment outcomes, however some gender-specific baseline predictors of treatment outcomes like use of multiple drugs, readiness for treatment, and spousal drug use were reported.[119] Studies that have used relapse as a measure of outcome have reported better outcome for women as compared to men.[107] Findings from project MATCH revealed that women not only have fewer chances of relapse but also more willingly sought help following a relapse and speculated the findings of gender by treatment modality to have an effect on the outcome.[120]

Generally, studies focusing on the association of treatment completion and outcome have indicated that treatment completion is associated with better outcomes, irrespective of gender.[121] In a study of patients recruited from drug treatment programs in Los Angeles County,[119] longer treatment retention was associated with drug abstinence and crime desistence for both men and women at 1-year follow-up. However, another study reported that women who completed treatment were 9 times as likely to be abstinent for 30 days at 7 months follow-up, while men who completed treatment were only 3 times as likely to be abstinent.[122]

Clinicians do agree that sensitivity to women's special needs and problems is critical to treatment success and some of the specific issues related to outcome may be: Co-occurring psychiatric disorders, history of victimization, therapist-patient gender matching, and social factors.[123]

Having a psychiatric comorbidity, in general, tend to predict poorer treatment outcomes, irrespective of gender, wherein the outcome was measured by total number of drinking days, greater intensity of drinking, more craving, increased likelihood of having a pathological pattern of alcohol use, and more withdrawal symptoms.[124] A prospective study studied the effects of depression on drinking outcomes among in-patients being treated for alcohol dependence and again did not find a gender difference in association between depression and time to first drink; they did, however, found that a diagnosis of major depression was associated with shorter time to first drink for both males and females.[125] On similar lines, two studies of the association of a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorders reported that, regardless of the gender, this co-occurring diagnosis was related to poor treatment outcome.[126,127]

Thus, it has been consistently found that the presence of co-morbid psychiatric disorders has a negative impact on substance abuse treatment response regardless of gender. However, some studies do give contrasting information in this regard. Benishek et al.[128] assessed more than 500 patients at intake and follow-up and found that a global measure of psychopathology was predictive of more alcohol problems 6 months posttreatment for women, but not for men. In studies using women-only sample, it has been seen that among women with substance use disorders, presence of co-morbid psychiatric disorders (effective or anxiety-related) or greater severity of PTSD, at baseline, predicted relapse during 6 months follow-up.[129,130] Surprisingly, a 1-year follow-up study in Germany found that though men with or without co-morbid psychiatric disorder had similar relapse rates, women with co-morbid psychiatric disorders had a lower rate of relapse as compared to women with no co-morbidity.[131] It has been hypothesized that women with co-occurring depression and alcohol use disorders may have more severe depression and less severe alcohol dependence as compared to men with both the disorders and hence the difference in the outcome.[132] Co-morbid eating disorder and its impact on treatment outcome are an area less explored in this regard despite the fact that they are commonly reported co-morbid conditions in treatment-seeking women.[133,134]

Victimization and abuse also tend to predict treatment outcomes, and the association has been reported between abuse and shorter time to first drink and relapse, regardless of the gender.[135] However, this association disappeared after accounting for other factors like marital status, education, employment, and co-morbid psychiatric disorders. The Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study, a quasi-experimental, multi-site cooperative study reported that certain individual-related variables, such as drug/alcohol use problem severity, mental health status, lifetime and current exposure to abuse and other stressful events predicted outcomes independent of intervention condition. They have also provided some evidence that comprehensive integrated services may be more effective treatment for women with co-occurring substance and psychiatric disorders and histories of physical/sexual abuse.[136,137,138,139]

Matching of therapist and client gender have also generated mixed results, with some studies not finding any effect on treatment-outcome,[140,141] while others reporting better outcomes in terms of abstinence.[142,143]

Other studies have sought social factors that might influence treatment outcome. MacDonald followed 93 alcoholic women for 1-year after inpatient treatment and found that the number of life problems and the number of supportive relationships were the best predictors of favorable outcome. Being married was less important as a predictor than the supportive quality of the patient's marriage.[144] Similar results have been reported by Havassy et al.,[145] who found a relationship between social support and time abstinent after detoxification from alcohol, methadone, and tobacco.

Thus, it can be said that both men and women benefit from the substance abuse treatment and that gender alone is not a predictor of outcome. However, certain characteristics of individuals, sub-groups of individuals, and treatment approaches may have a differential impact on treatment-related outcomes by gender.

GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE

Over the years, Western countries have recognized the need to study and address the issues pertaining to FSUs. However, in India, there is still a lack of research-based information on all aspects of women's substance use and related problems, including pattern and prevalence, physiological and psychosocial effects and consequences, characteristics of women with substance use problems, and their treatment experiences. Thus, drug abuse among women needs to be studied in a more systematic fashion using both qualitative and quantitative methods of research and through multi-centered studies.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although predominantly thought to be a male phenomenon, drug abuse exists among women and in current urban settings appears to be associated with patterns of drug abuse similar to that of men. Though drug use generally starts later in women or is iatrogenically introduced, it follows a more rapid downhill course, with rapid progression through the stages of dependence and with more associated psychological and physical morbidity. The stigma of being a “fallen angel” makes these women an easy victim to the ills of the society and prevents them from seeking help early in the course of the illness. Stigma drives them to darkness, forcing them to resort to higher-risk behaviors of unsafe injecting and unsafe sexual practices. Though involvement in criminal activity and drug pedaling is less than it is in males, commercial or forced sexual activity to sustain drug use often brings them at conflict with law with all its ramifications, apart from the obvious health hazards of such behaviors. Social and familial support is minimal for them and particularly so if the spouse is nondrug using partner. When women do come forward for treatment, they are faced with the lack of gender-sensitive treatment programs and flexible treatment delivery systems that account for their limitations and increased home responsibilities. Many thus are left with no choice but to continue drug use in even more dangerous patterns without any hope for future. Thus, there is an urgent need for treatment and prevention approaches to consider the problem of drug abuse impact on women from all these angles, as well as from the context of empowerment, support, and de-stigmatization of women. It is thus imperative to evolve a focused policy to address gender issues in relation to drug abuse and to develop treatment modalities that are gender-responsive or sensitive to needs of women, such as counseling, family therapy. Ancillary services such as transportation, child-care, housing, vocational training, and diverse cultural contexts need to be taken care of. Only then will the country be able to provide its women drug user a ray of hope.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Marshall M. University of Michigan Press; 1979. Beliefs, Behaviors, & Alcoholic Beverages: A Cross-cultural Survey; p. 508. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blume SB. Sexuality and stigma: The alcoholic woman. Alcohol Health Res World. 1991;15:139–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blume S, Zilberman M. Alcohol and Women. In: Lowinson J, Ruiz P, Millman R, Langrod J, editors. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. 4th ed. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilsnack S, Wilsnack R. International Gender and Alcohol Research: Recent Findings and Future Directions [Internet] NIAAA. 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh26-4/245-250.htm . [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grucza RA, Norberg K, Bucholz KK, Bierut LJ. Correspondence between secular changes in alcohol dependence and age of drinking onset among women in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helzer J, Burnam A, McEvoy L. Alcohol abuse and dependence. In: Robins L, Regier D, editors. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York: The Free Press; 1991. pp. 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHugh RK, Wigderson S, Greenfield SF. Epidemiology of substance use in reproductive-age women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:177–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simoni-Wastila L, Ritter G, Strickler G. Gender and other factors associated with the nonmedical use of abusable prescription drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:1–23. doi: 10.1081/ja-120027764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHSDA . Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2001. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Summary of findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilsnack S, Wilsnack R. International Gender and Alcohol Research: Recent Findings and Future Directions. NIAAA. 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh26-4/245-250.htm . [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Benegal V, Nayak M, Murthy P, Chandra P, Gururaj G. 2005. Women and alcohol in India. In: Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems. Perspectives from Low and Middle Income Countries. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohan D, Desai N. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1993. A Survey on Drug Dependence in the Community, Urban Megapolis, Delhi. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan D, Sundaram K. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Welfare, Government of India and All India Institute of Medical Science; 1987. A Multi-Centred Study of Drug Abuse among Students: A Preliminary Report. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohan D. Prevalence of drug abuse among university students: Preliminary report of a multi-centre survey. In: Mohan D, Sethi H, Tongue E, editors. Current Research in Drug Abuse in India. New Delhi, India: Gemini Printers; 1981. pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Channabasavanna S, Ray R, Kaliaperumal V. Karnataka, India: Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Karnataka; 1990. Patterns and Problems of Non-Alcoholic Drug Dependence in Karnataka. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohan D, Ray R, Sharma S, Desai N, Tripathi B, Purohit D, et al. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1993. Collaborative Study on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh A, Kaul R, Sharma S. Survey of Drug Abuse in Manipur State. Department of Science, Technology and Environment, Government of Manipur. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapoor S, Pavamani V, Mittal S. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and UNDCP, ROSA; 2001. Substance Abuse among Women in India. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mondol J. Kolkota, India: Vivekananda Education Society; 1992. A Study on Women, the Family and Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shankardass M. New Delhi, India: UNDCP, ROSA; 1998. Women's Health Issues with Special Reference to Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ray R, Mondal AB, Gupta K, Chatterjee A, Bajaj P. New Delhi: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia and Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2004. The Extent, Pattern and Trends of Drug Abuse in India: National Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy P. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2008. Women and Drug use in India: Substance, Women and High-risk Assessment Study. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2000. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-2 (1998-1999) Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs2.shtml . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geneva: World Health Organization, Dept. of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; 2004. WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International. National Family Health Survey-3, 2005-2006. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs3.shtml . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grover S, Irpati AS, Saluja BS, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Substance-dependent women attending a de-addiction center in North India: Sociodemographic and clinical profile. Indian J Med Sci. 2005;59:283–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potukuchi PS, Rao PG. Problem alcohol drinking in rural women of Telangana region, Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:339–43. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.74309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caixeta RB, Khoury RN, Sinha DN, Rarick J, Tong V, Dietz P, et al. Current tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure among women of reproductive age - 14 Countries, 2008-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:877–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prabhakar B, Narake SS, Pednekar MS. Social disparities in tobacco use in India: The roles of occupation, education and gender. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:401–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nebhinani N, Sarkar S, Gupta S, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Demographic and clinical profile of substance abusing women seeking treatment at a de-addiction center in North India. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:12–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.123587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kermode M, Sono CZ, Songput CH, Devine A. Falling through the cracks: A qualitative study of HIV risks among women who use drugs and alcohol in Northeast India. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaturvedi HK, Mahanta J, Bajpai RC, Pandey A. Correlates of opium use: Retrospective analysis of a survey of tribal communities in Arunachal Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha R, Fox H, Hong KI, Sofuoglu M, Morgan PT, Bergquist KT. Sex steroid hormones, stress response, and drug craving in cocaine-dependent women: Implications for relapse susceptibility. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:445–52. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Back SE, Waldrop AE, Saladin ME, Yeatts SD, Simpson A, McRae AL, et al. Effects of gender and cigarette smoking on reactivity to psychological and pharmacological stress provocation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:560–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox HC, Hong KA, Paliwal P, Morgan PT, Sinha R. Altered levels of sex and stress steroid hormones assessed daily over a 28-day cycle in early abstinent cocaine-dependent females. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;195:527–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0936-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doron R, Fridman L, Gispan-Herman I, Maayan R, Weizman A, Yadid G. DHEA, a neurosteroid, decreases cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2231–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newman J, Mello N. Guilford Press: New York; 2009. Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook; pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baraona E, Abittan CS, Dohmen K, Moretti M, Pozzato G, Chayes ZW, et al. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:502–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seitz HK, Egerer G, Simanowski UA, Waldherr R, Eckey R, Agarwal DP, et al. Human gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity: Effect of age, sex, and alcoholism. Gut. 1993;34:1433–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.10.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Thiel DH, Tarter RE, Rosenblum E, Gavaler JS. Ethanol, its metabolism and gonadal effects: Does sex make a difference? Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 1988;7:131–69. doi: 10.1300/J251v07n03_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tobin MB, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Reported alcohol use in women with premenstrual syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1503–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen D. Are alcoholic women more likely to drink premenstrually? Alcohol Alcohol. 1996;31:145–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeman MV, Hiraki L, Sellers EM. Gender differences in tobacco smoking: Higher relative exposure to smoke than nicotine in women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:147–53. doi: 10.1089/152460902753645281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perkins KA, Levine M, Marcus M, Shiffman S, D’Amico D, Miller A, et al. Tobacco withdrawal in women and menstrual cycle phase. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:176–80. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corchero J, Manzanares J, Fuentes JA. Role of gonadal steroids in the corticotropin-releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin gene expression response to Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol in the hypothalamus of the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74:185–92. doi: 10.1159/000054685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zun LS, Downey LV, Gossman W, Rosenbaumdagger J, Sussman G. Gender differences in narcotic-induced emesis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:151–4. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.32631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han C, McGue MK, Iacono WG. Lifetime tobacco, alcohol and other substance use in adolescent Minnesota twins: Univariate and multivariate behavioral genetic analyses. Addiction. 1999;94:981–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van den Bree MB, Johnson EO, Neale MC, Pickens RW. Genetic and environmental influences on drug use and abuse/dependence in male and female twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;52:231–41. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Cannabis use, abuse, and dependence in a population-based sample of female twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1016–22. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Cocaine use, abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of female twins. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:345–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Selvaraj V, Suveera P, Ashok MV, Appaya MP. Women alcoholics: Are they different from men alcoholics? Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:288–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murthy P, Chand P. Substance use disorder in women. In: Lal R, editor. Substance Use Disorder Manual for Physicians. New Delhi, India: National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences; 2005. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. pp. S170–S7. Available from: http://www.aiims.edu/aiims/departments/spcenter/nddtc/nddtc_publi.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown C, Madden PA, Palenchar DR, Cooper-Patrick L. The association between depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking in an urban primary care sample. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2000;30:15–26. doi: 10.2190/NY79-CJ0H-VBAY-5M1U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dale LC, Glover ED, Sachs DP, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Bupropion for smoking cessation: Predictors of successful outcome. Chest. 2001;119:1357–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winfield I, George LK, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Sexual assault and psychiatric disorders among a community sample of women. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:335–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ullman SE, Relyea M, Peter-Hagene L, Vasquez AL. Trauma histories, substance use coping, PTSD, and problem substance use among sexual assault victims. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, Walters EE, Swendsen JD, Aguilar-Gaziola S, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: Results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav. 1998;23:893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zilberman ML, Tavares H, Andrade AG. Discriminating drug-dependent women from alcoholic women and drug-dependent men. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1343–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peiper N, Rodu B. Evidence of sex differences in the relationship between current tobacco use and past-year serious psychological distress: 2005-2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1261–71. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0644-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, Wang S, Pérez-Fuentes G, Kerridge BT, et al. Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan S, Okuda M, Hasin DS, Secades-Villa R, Keyes K, Lin KH, et al. Gender differences in lifetime alcohol dependence: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1696–705. doi: 10.1111/acer.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:339–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holderness CC, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Co-morbidity of eating disorders and substance abuse review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:1–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199407)16:1<1::aid-eat2260160102>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Hook J, Fairburn CG. Self-harm and substance use in a community sample of Black and White women with binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:389–400. doi: 10.1002/eat.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finkelstein N. Treatment programming for alcohol and drug-dependent pregnant women. Int J Addict. 1993;28:1275–309. doi: 10.3109/10826089309062189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carter CS. Ladies don’t: A Historical perspective on attitudes toward alcoholic women. Affilia. 1997;12:471–85. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maharaj RG, Rampersad J, Henry J, Khan KV, Koonj-Beharry B, Mohammed J, et al. Critical incidents contributing to the initiation of substance use and abuse among women attending drug rehabilitation centres in Trinidad and Tobago. West Indian Med J. 2005;54:51–8. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442005000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kermode M, Songput CH, Sono CZ, Jamir TN, Devine A. Meeting the needs of women who use drugs and alcohol in North-east India – A challenge for HIV prevention services. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:825. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hser YI, Anglin MD, Booth MW. Sex differences in addict careers 3. Addiction. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13:231–51. doi: 10.3109/00952998709001512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Randall CL, Roberts JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Mattson ME. Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: A gender comparison. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:252–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hernandez-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kandel DB, Chen K. Extent of smoking and nicotine dependence in the United States: 1991-1993. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:263–74. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. The course of early smoking: A population-based cohort study over three years. Addiction. 1998;93:1251–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.938125113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Powis B, Griffiths P, Gossop M, Strang J. The differences between male and female drug users: Community samples of heroin and cocaine users compared. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31:529–43. doi: 10.3109/10826089609045825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rey JM, Sawyer MG, Raphael B, Patton GC, Lynskey M. Mental health of teenagers who use cannabis. Results of an Australian survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:216–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. SAMHSA. Daily Marijuana Users Based on the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gfroerer J, Wu LT, Penne M. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies; 2002. Initiation of Marijuana Use: Trends, Patterns, and Implications. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hanna E, Dufour MC, Elliott S, Stinson F, Harford TC. Dying to be equal: Women, alcohol, and cardiovascular disease. Br J Addict. 1992;87:1593–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of coronary disease and stroke in women. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:267–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808043190503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Altura BM, Altura BT. Association of alcohol in brain injury, headaches, and stroke with brain-tissue and serum levels of ionized magnesium: A review of recent findings and mechanisms of action. Alcohol. 1999;19:119–30. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ashley MJ, Olin JS, le Riche WH, Kornaczewski A, Schmidt W, Rankin JG. Morbidity in alcoholics. Evidence for accelerated development of physical disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:883–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.137.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumar MS, Sharma M. Women and substance use in India and Bangladesh. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1062–77. doi: 10.1080/10826080801918189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trocki KF, Leigh BC. Alcohol consumption and unsafe sex: A comparison of heterosexuals and homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:981–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gupta J, Raj A, Decker MR, Reed E, Silverman JG. HIV vulnerabilities of sex-trafficked Indian women and girls. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crome IB, Kumar MT. Epidemiology of drug and alcohol use in young women. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pelissier B, Jones N. A review of gender differences among substance abusers. Crime Delinq. 2005;51:343–72. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schober R, Annis HM. Barriers to help-seeking for change in drinking: A gender-focused review of the literature. Addict Behav. 1996;21:81–92. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dawson DA. Gender differences in the probability of alcohol treatment. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8:211–25. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Swift W, Copeland J, Hall W. Characteristics of women with alcohol and other drug problems: Findings of an Australian national survey. Addiction. 1996;91:1141–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91811416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mojtabai R. Use of specialty substance abuse and mental health services in adults with substance use disorders in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:345–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Timko C, Moos RH, Finney JW, Lesar MD. Long-term outcomes of alcohol use disorders: Comparing untreated individuals with those in alcoholics anonymous and formal treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:529–40. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu LT, Ringwalt CL. Alcohol dependence and use of treatment services among women in the community. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1790–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.10.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ray R, Chopra A. Monitoring of substance abuse in India - Initiatives and experiences. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:806–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Basu D, Aggarwal M, Das PP, Mattoo SK, Kulhara P, Varma VK. Changing pattern of substance abuse in patients attending a de-addiction centre in North India (1978-2008) Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:830–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sreejayan K, Benegal V. Treatment of women drug users: Special issues. In: Tripathi B, editor. Drug Abuse: News-n-Views. New Delhi: National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ayyagari S, Boles S, Johnson P, Kleber H. Difficulties in recruiting pregnant substance abusing women into treatment: Problems encountered during the Cocaine Alternative Treatment Study. Abstr Book Assoc Health Serv Res. 1999;16:80–1. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Grella CE. Services for perinatal women with substance abuse and mental health disorders: The unmet need. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1997;29:67–78. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1997.10400171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paltrow L. Punishing women for their behavior during pregnancy: An approach that undermines the health of women and children. In: Wetherington C, Roman A, editors. Drug Addiction Research and the Health of Women. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. pp. S467–S502. Available from: http://www.reproductiverights.org/document/punishing-women-for-their-behavior-during-pregnancy-an-approach-thatundermines-womens-heal . [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sonne SC, Back SE, Diaz Zuniga C, Randall CL, Brady KT. Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Addict. 2003;12:412–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van Olphen J, Freudenberg N. Harlem service providers’ perceptions of the impact of municipal policies on their clients with substance use problems. J Urban Health. 2004;81:222–31. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brady T, Ashley O. Women in Substance Abuse Treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS) 2005. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.drugabusestatistics.samhsa.gov/womenTX/womenTX.htm .

- 109.Arfken CL, Klein C, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Gender differences in problem severity at assessment and treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20:53–7. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hser YI, Huang YC, Teruya C, Anglin MD. Gender differences in treatment outcomes over a three-year period: A path model analysis. J Drug Issues. 2004;34:419–40. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Green CA, Polen MR, Dickinson DM, Lynch FL, Bennett MD. Gender differences in predictors of initiation, retention, and completion in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:285–95. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Maglione M, Chao B, Anglin D. Residential Treatment of Methamphetamine Users: Correlates of Drop-Out from the California Alcohol and Drug Data System (Cadds), 1994-1997. Addict Res Theory. 2000;8:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Veach LJ, Remley TP, Jr, Kippers SM, Sorg JD. Retention predictors related to intensive outpatient programs for substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:417–28. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kohn CS, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Coping among individuals seeking private chemical dependence treatment: Gender differences and impact on length of stay in treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1228–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000023987.87116.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kelly PJ, Blacksin B, Mason E. Factors affecting substance abuse treatment completion for women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2001;22:287–304. doi: 10.1080/01612840152053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ashley OS, Marsden ME, Brady TM. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: A review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Floyd AS, Monahan SC, Finney JW, Morley JA. Alcoholism treatment outcome studies, 1980-1992: The nature of the research. Addict Behav. 1996;21:413–28. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N, Addington J. Treatment of substance abusers: Single or mixed gender programs? Addiction. 1997;92:805–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hser YI, Huang D, Teruya C, Douglas Anglin M. Gender comparisons of drug abuse treatment outcomes and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:255–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cutler RB, Fishbain DA. Are alcoholism treatments effective? The Project MATCH data. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Messina N, Wish E, Nemes S. Predictors of treatment outcomes in men and women admitted to a therapeutic community. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:207–27. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Green CA, Polen MR, Lynch FL, Dickinson DM, Bennett MD. Gender differences in outcomes in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. J Addict Dis. 2004;23:47–70. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schliebner CT. Gender-sensitive therapy. An alternative for women in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994;11:511–5. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kranzler HR, Del Boca FK, Rounsaville BJ. Comorbid psychiatric diagnosis predicts three-year outcomes in alcoholics: A posttreatment natural history study. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:619–26. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, Vagge LM, Kelly JF, Bello LR, et al. The effect of depression on return to drinking: A prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:259–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Galen LW, Brower KJ, Gillespie BW, Zucker RA. Sociopathy, gender, and treatment outcome among outpatient substance abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;61:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hesselbrock M, Hesselbrock V. Gender, alcoholism, and psychiatric comorbidity. In: Wilsnack R, Wilsnack S, editors. Gender and Alcohol: Individual and Social Perspective. New Jersey: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1997. pp. 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Benishek LA, Bieschke KJ, Stöffelmayr BE, Mavis BE, Humphreys KA. Gender differences in depression and anxiety among alcoholics. J Subst Abuse. 1992;4:235–45. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(92)90032-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Brady KT, Killeen T, Saladin ME, Dansky B, Becker S. Comorbid substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Addict. 1994;3:160–4. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Brown PJ. Outcome in female patients with both substance use and post-traumatic stress disorders. Alcohol Treat Q. 2000;18:127–35. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mann K, Hintz T, Jung M. Does psychiatric comorbidity in alcohol-dependent patients affect treatment outcome? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:172–81. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pettinati HM, Rukstalis MR, Luck GJ, Volpicelli JR, O’Brien CP. Gender and psychiatric comorbidity: Impact on clinical presentation of alcohol dependence. Am J Addict. 2000;9:242–52. doi: 10.1080/10550490050148071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gordon SM, Johnson JA, Greenfield SF, Cohen L, Killeen T, Roman PM. Assessment and treatment of co-occurring eating disorders in publicly funded addiction treatment programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1056–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.9.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Taylor AV, Peveler RC, Hibbert GA, Fairburn CG. Eating disorders among women receiving treatment for an alcohol problem. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;14:147–51. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199309)14:2<147::aid-eat2260140204>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Greenfield SF, Hufford MR, Vagge LM, Muenz LR, Costello ME, Weiss RD. The relationship of self-efficacy expectancies to relapse among alcohol dependent men and women: A prospective study. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:345–51. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cocozza JJ, Jackson EW, Hennigan K, Morrissey JP, Reed BG, Fallot R, et al. Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: Program-level effects. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Markoff LS, Finkelstein N, Kammerer N, Kreiner P, Prost CA. Relational systems change: Implementing a model of change in integrating services for women with substance abuse and mental health disorders and histories of trauma. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2005;32:227–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.McHugo GJ, Kammerer N, Jackson EW, Markoff LS, Gatz M, Larson MJ, et al. Women, Co-occurring disorders, and violence study: Evaluation design and study population. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:91–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Morrissey JP, Ellis AR, Gatz M, Amaro H, Reed BG, Savage A, et al. Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: Program and person-level effects. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.McKay JR, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, Shepard DS. An examination of potential sex and race effects in a study of continuing care for alcohol- and cocaine-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1321–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080347.11949.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sterling RC, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Serota R. The effect of therapist/patient race- and sex-matching in individual treatment. Addiction. 2001;96:1015–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967101511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Fiorentine R, Anglin MD, Gil-Rivas V, Taylor E. Drug treatment: Explaining the gender paradox. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:653–78. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Sterling RC, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Serota R. Therapist/patient race and sex matching: Treatment retention and 9-month follow-up outcome. Addiction. 1998;93:1043–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93710439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Macdonald JG. Predictors of treatment outcome for alcoholic women. Int J Addict. 1987;22:235–48. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Havassy BE, Hall SM, Tschann JM. Social support and relapse to tobacco, alcohol, and opiates: Preliminary findings. NIDA Res Monogr. 1987;76:207–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]