Abstract

A growing body of research suggests that mindfulness- and acceptance-based principles can increase efforts aimed at reducing human suffering and increasing quality of life. A critical step in the development and evaluation of these new approaches to treatment is to determine the acceptability and efficacy of these treatments for clients from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds. This special series brings together the wisdom of clinicians and researchers who are currently engaged in clinical practice and treatment research with populations who are historically underrepresented in the treatment literature. As an introduction to the series, this paper presents a theoretical background and research context for the papers in the series, highlights the elements of mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments that may be congruent with culturally responsive treatment, and briefly outlines the general principles of cultural competence and responsive treatment. Additionally, the results of a meta-analysis of mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments with clients from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds are presented. Our search yielded 32 studies totaling 2,198 clients. Results suggest small (Hedges' g=.38, 95% CI=.11 − .64) to large (Hedges' g=1.32, 95% CI=.61 − 2.02) effect sizes for mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments, which varied by study design.

Keywords: mindfulness, acceptance, cultural competence, treatment, meta-analysis

A growing body of treatment outcome research suggests that the integration of acceptance and mindfulness principles with cognitive behavior therapies shows promise in ameliorating human suffering and improving quality of life (Baer, 2003; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004). Acceptance- and mindfulness-based principles have been effectively integrated into behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder (Linehan, 1993), depression (Bohlmeijer, Fledderus, Rokx, & Pieterse, 2011) and depression relapse (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002), bipolar disorder (Williams et al., 2008), substance abuse (Bowen et al., 2009; Hayes, 2004; Marlatt, 2002), anxiety disorders (Orsillo & Roemer, 2005), eating disorders (Baer, Fischer, & Huss, 2005), psychosis (Bach & Hayes, 2002; Gaudiano & Herbert, 2006), chronic pain (Dahl, Wilson, Luciano, & Hayes, 2005) and stress reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 2003) with favorable outcomes. Despite growing evidence for the efficacy of acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments across a range of disorders, the generalizability of these findings is limited by samples that do not represent the full demography of the U.S. population. In particular, research on the relevance to and acceptability of these treatments with individuals from nondominant, traditionally underserved backgrounds is in its infancy.

The demographic composition of the United States is shifting and rapid growth is predicted for groups that have traditionally been underserved with regard to mental health services. In approximately 30 years, it is projected that non-Hispanic, single race Whites will become the minority in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Further, by 2030, nearly one in five U.S. residents are predicted to be aged 65 or older (Vincent & Velkoff, 2010). Thus, considering the ways in which traditional psychotherapy practices may not fit with the values and worldviews of this changing population has never been more important. Additionally, despite the growing population of racial and ethnic minorities and the significant increase in attention to cultural competence in mental health treatment, inequities in access to quality mental health services continue to exist (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Some have argued that prior to conducting costly randomized controlled trials of standard evidence-based therapies with underserved populations, guidelines about possible treatment adaptations should be established, with careful attention to maintaining the fidelity to treatment principles (Lau, 2006). At the same time, some critics contend that adapting evidence-based treatments for different cultural groups is inefficient and unjustified (Elliott & Mihalic, 2004). Although it is certainly true that a goal of developing treatment variations for every cultural group is impractical and likely unhelpful, broadly disseminating evidence-based treatments without considering the culturally relevant adaptations or refinements that might increase their effectiveness has the potential to widen the gap of mental health disparities in this country.

The overall goal of this series is to provide evidence-based and conceptually grounded suggestions to front-line clinicians working with individuals from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds on how acceptance- and mindfulness-based behavioral treatment approaches might be used in ways that are relevant and engaging. We also hope that these suggestions will inform future research of acceptance and mindfulness-based treatment approaches with diverse, underserved populations. This introduction is intended to provide a theoretical background and empirical context for the papers in this series, in addition to an overview of the series. We discuss aspects of acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatment approaches that may lend themselves particularly to culturally responsive treatment, while also highlighting general principles of cultural competence and responsive care that should inform all forms of intervention. Finally, we present findings from a meta-analysis of studies that have examined the efficacy of mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments with clients from underserved backgrounds.

Acceptance-Based Behavioral Therapies

It has been suggested that Western/dominant cultural values are inherent in many current evidence-based treatments (Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011). In particular, the emphasis placed in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) on individualism, present functioning, assertiveness, rationality, and behavior change reflects values that may not be shared by all clients, particularly those from non-Western/nondominant cultural backgrounds (Hays, 2009). In contrast, recent evolutions in CBT highlight the contextual and functional nature of psychological processes and behaviors rather than just their form or frequency, which may be a less value-laden approach to facilitating meaningful behavior change (Hayes, 2004). For example, curiously exploring the function of disruptive thoughts—with the goal of helping clients develop different relationships to the thoughts— may be experienced as more collaborative and less pejorative for clients, as opposed to highlighting the irrational content of those thoughts in order to change the content and frequency of those thoughts. In particular, treatments that emphasize the role of acceptance- and mindfulness-based principles, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993), Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1991), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2002), and integrations of these approaches (e.g., Roemer & Orsillo, 2009), may show promise in addressing some of the unique concerns of individuals from non-dominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds.

The terms acceptance-based behavioral therapies (ABBTs) and acceptance- and mindfulness-based therapies have been used to categorize the aforementioned treatment approaches as they share an emphasis on altering clients' relationships to unwanted internal experiences (Roemer & Orsillo, 2009). Whereas traditional CBT approaches generally focus on evaluating the accuracy of internal responses like thoughts or feelings, with the goal of changing their form, ABBT approaches highlight the ways in which certain responses to internal experiences can disrupt functioning and reduce quality of life. Specifically, from an ABBT perspective, client problems are conceptualized as resulting from a pattern of responding to internal experiences with judgment, confusion, and avoidance. Clinically, strategies like mindfulness are used to help clients to compassionately observe their thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations, accept them as transient, inherently human experiences, and become willing to engage in meaningful activities even if doing so could elicit discomfort. While the form and recommended frequency of clinical methods may differ across treatments, cultivating a stance of mindfulness, defined as “an open-hearted, moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness” (Kabat-Zinn, 2005, p. 24), is one of the core strategies used in many ABBTs to facilitate acceptance of internal experiences and reduce experiential avoidance. MBSR and MBCT recommend extended formal meditation practices whereas DBT utilizes brief, flexible, skills-based practice of mindfulness. The encouragement of engaging in actions that are consistent with one's values (termed as valued actions in ACT [Hayes et al., 1999]) with a willingness to experience the internal experiences that might accompany those actions is another element of some ABBTs, particularly ACT and DBT.

ABBTs and Underserved Populations

There are several ways that ABBTs may be particularly relevant to people from marginalized and/or underserved backgrounds. The therapeutic stance in many ABBTs is that the client's experience is influenced by sociopolitical and historical factors that affect the way that distress is experienced and expressed (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). Emotional distress is viewed as a universal human experience that is inevitable and natural. Thus, a focus of these treatmentsisgenerally to understand the context in which a client is experiencing distress and normalize and validate that distress before encouraging values-consistent behavioral change. This contextualized approach may resonate with clients from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds who, due to understandable mistrust of the mental health system, may assume that they will be blamed in therapy for their current circumstances.

The dialectical stance, taken in some acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments (DBT, ACT), which involves empathically connecting with a client's distress, while also challenging the client to move towards life-enhancing behavioral change as well as an emphasis on engaging in actions consistent with one's values, may resonate with clients who feel that they lack control over their environment due to systemic oppression and discrimination. Given the things that individuals from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds have relatively little control over (i.e., oppressive beliefs held by others, systemic oppression, etc.), validating this reality while also helping these individuals identify the actions that are within their control and consistent with what matters most to them, may be extremely helpful. This unique combination of validation and change also has the potential to minimize the power dynamic inherent in traditional psychotherapeutic communication and facilitate a collaborative therapeutic alliance. Additionally, the exploration of client-specific values and valued actions allows for a consideration of the role of cultural and familial expectations that may or may not be in line with a client's own values.

Metaphors, which are often used in ABBTs to illustrate principles of mindfulness and acceptance, may be particularly helpful when working with clients who are from a cultural background where emotional distress and other psychological processes are viewed as a sign of weakness. Perceived stigma has been demonstrated to be related to willingness to receive mental health services among members of traditionally underserved populations such as African Americans and older adults (Conner et al., 2010). Using metaphors to validate distress and illustrate more effective ways of responding to internal experience may serve to normalize psychological challenges. As will be discussed in this series, metaphors can also be easily adapted and personalized to best match the life experiences of a particular client or cultural group.

Psychoeducation and skill-building is a component of many CBTs and is heavily emphasized in many ABBTs. For clients from cultural backgrounds in which psychological difficulties are highly stigmatized or psychotherapy is infrequently utilized, this emphasis may serve to destigmatize psychotherapy and increase engagement. Older adults, in particular, have been found to require more psychoeducation about the process of therapy than younger adults, as they are often less familiar with the purpose and function of therapy (Edelstein, Northrop, & MacDonald, 2009). Roth and Robbins (2004) found that promoting MBSR as an educational program rather than a mental health program was an effective method to address apprehension of seeking mental health services among Hispanic women.

Culturally Competent and Responsive Mental Health Care

Although ABBTs may lend themselves to culturally responsive mental health care in many ways, therapists must also explicitly consider culture and culturally competent care when working with each client. We provide a brief overview of elements of culturally responsive therapy (see Hays, 2008; Lee, Fuchs, Roemer, & Orsillo, 2009; D. W. Sue & Sue, 2003, for more in-depth discussions of these important issues).

“Culture” has been defined broadly as a person's worldview, which is shaped by life experiences and affects the way a person interacts with the world (Pedersen & Ivey, 1993). In understanding some of the relevant dimensions of an individual's cultural identity, Hays (2008) has provided a useful heuristic, known by the acronym ADDRESSING, that includes aspects of a person's (1) Age and generational influences, (2) Developmental and acquired Disabilities, (3) Religion and spiritual orientation, (4) Ethnicity, (5) Socioeconomic status, (6) Sexual orientation, (7) Indigenous heritage, (8) National origin, and (9) Gender. Race, which refers to the social construction of categorizing people into groups on the basis of physical characteristics, is also an important component of one's identity, particularly given the effects that racism can have on a person's sense of self and beliefs about others (cf. Helms & Talleyrand, 1997). An individual's cultural identity is dynamic, in flux, and context dependent as he/she interacts with an ever-changing world. Thus, it has been suggested that it is important to know when to apply general knowledge about cultural groups to understanding a client's experience and when to flexibly individualize treatment to a particular client's circumstances and context (S. Sue, 1998). Those who are from nondominant cultural backgrounds may hold worldviews that are different from the worldview of a dominant culture. These often disparate worldviews are reflective of different experiences in the larger social context.

Clinical psychology has generally been criticized for deemphasizing the importance of viewing individuals within their multicultural and community contexts, instead focusing too narrowly on the individual in isolation (Nagayama Hall, 2005). One cost associated with such a narrow focus is that important sociocultural factors that may be influencing client behaviors will not be explored in therapy, which can inadvertently lead clients to feel that they are to blame for their distress. Clients, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds who may come to therapy with some skepticism about its effectiveness (S. Sue, 2006), may feel misunderstood or unheard when the full context of their life is not attended to, resulting in early termination of therapy (Comas-Diaz, 2006). A critical element of providing culturally competent mental health care involves understanding the barriers and challenges that socially marginalized communities face (D. W. Sue & Sue, 2003). This means that not only do therapists have to explore these barriers in therapy, but they also have to be mindful of their own cultural biases that might prevent them from considering the worldviews of their clients.

Cultural competence has been defined as an approach to therapy, rather than a therapeutic technique (S. Sue, 1998). Therefore, it should be integrated into all aspects of a therapeutic encounter, regardless of the treatment modality. Bernal, Bonilla, and Bellido (1995) proposed a framework for culturally sensitive interventions with ethnic minorities that could be applied more broadly to individuals from nondominant cultural backgrounds and/or marginalized populations. The framework includes eight dimensions that should be integrated into psychological treatments: (1) language, (2) persons, (3) metaphors, (4) content, (5) concepts, (6) goals, (7) methods, and (8) context. Language not only provides important information about a person's culture, but it also relates to the expression and experience of emotions (Barona & Santos de Barona, 2003). Attention to persons reflects the need to attend to similarities and differences between the therapist and the client. Metaphors can be seen as important symbols that reflect cultural values and norms that, if accurately incorporated into treatment, can help a client feel respected and understood. Being knowledgeable about the content of a client's culture can help therapists integrate that content into all aspects of treatment. Careful attention to the cultural context of a client's life is also important when considering the manner in which therapeutic concepts are communicated to a client. Establishing collaborative treatment goals that incorporate the values and norms of a client's culture is crucial. The methods used to achieve the treatment goals must be congruent with a client's culture; that is, the use of clinical methods should be transparent and collaborative. Finally, the sociopolitical contexts of clients' lives, including discrimination, oppression, and socialization, need to considered as they relate to a client's presenting issues and the treatment plan.

In general, mental health providers are most effective when they can flexibly shift their therapeutic focus to meet the needs of their clients (D. W. Sue & Sue, 2003). Client-centered approaches to treatment naturally facilitate culturally responsive mental health treatment. This suggests that evidence-based treatments need to be used flexibly and attentively to ensure that client's needs are not overlooked in the service of adhering rigidly to the treatment. While learning about the customs and norms within a particular community is important, a therapeutic stance that emphasizes awareness of cultural factors that may be related to presenting problems and engagement with treatment is likely to be more helpful. Although it certainly seems that the emphasis on understanding clients' contexts and values and the therapeutic stance characteristic of acceptance- and mindfulness-based behavioral treatments makes them well-suited for use with nondominant cultural and/or marginalized populations, more information is needed to determine their efficacy, explore their acceptability, and identify adaptations that could be helpful. This information should come from clinical research, as well as clinical practice. We hope that this series will serve as a first step towards disseminating information and insights gained from both clinical practice and research that will aid clinicians and researchers working with these populations.

Finally, in an effort to determine the current status of clinical research on the effectiveness of these treatments with nondominant cultural and/or marginalized populations, we recently expanded a previous meta-analytic review of the published empirical literature that used mindfulness- and acceptance-based behavioral treatments with individuals from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds (Lee et al., 2009). To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analytic investigation that systematically explores the potential utility of acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments with clients from diverse backgrounds.

Meta-Analysis of Acceptance- and Mindfulness-Based Behavioral Treatments With Underserved Populations

As noted previously, the literature base on the use of acceptance and mindfulness-based treatments with underserved populations is steadily growing. As a result, we conducted a meta-analytic review of the published and unpublished empirical studies to date that have used mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments with individuals from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds; more specifically individuals who are not traditionally the focus of psychological treatment outcome studies and for whom a consideration of contextual factors is particularly important in treatment.

Method

We undertook a review of the published empirical studies to date (as of September 2011) that have used acceptance- and mindfulness-based behavioral treatments with underserved populations. We conducted an electronic literature search of PsychInfo using the key words Mindfulness, Acceptance, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Acceptance-based Behavior Therapy (ABBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). Our search yielded 292 empirical treatment studies with a potential focus on underserved populations. Additionally, we also posted requests for doctoral dissertations, studies that were in press, and unpublished studies on relevant Listservs, which resulted in seven additional studies (three of which did not fit our criteria).

Among the 292 studies yielded by our search, we selected studies with individuals who are not traditionally the focus of psychological treatment outcome studies, are considered marginalized or underserved with respect to mental health treatment accessibility and modality, and for whom a consideration of contextual factors would be particularly important in treatment. Therefore, we selected studies that included only individuals who were either: (a) non-White, (b) non-European American, (c) older adults, (d) nonheterosexual, (e) low-income, (f) physically disabled, (g) incarcerated, and/or (h) individuals whose first language is not that of the dominant culture. We excluded studies that were not conducted in person (i.e., self-help manuals, telephone therapy) and case studies. This resulted in 35 studies from 33 peer-reviewed articles and one dissertation. Three studies reported insufficient information to estimate the effect size (i.e., Bowen et al., 2006, 2009; Liehr & Diaz, 2010) and thus were omitted from the review. This resulted in 32 studies that were retained for analysis, and included 2,198 participants (see Table 1).

Table1. Studies Included in Meta-Analysis.

| Authors | Population / Setting | TX | Design | N | Number of Outcoms | g | 95%-CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradley and Follingstad, 2003 | Forensic | DBT | No-Contact | 31 | 9 | .96 | .23–1.70 | .01 |

| Comtois et al., 2007 | Community | DBT | Pre-Post | 23 | 7 | .43 | .01–.76 | .01 |

| Evershed et al., 2003 | Forensic | DBT | DBT vs.TAU | 17 | 14 | .50 | -.45–1.45 | .31 |

| Garland et al., 2010 | 60% African American | MBCT-based | MBCT-based vs. Active (Alcohol Support Group) | 37 | 6 | .43 | -.22–1.07 | .19 |

| Gaudiano and Herbert, 2006 | 88% minority | ACT | ACT+ETAU vs. ETAU | 29 | 8 | .37 | -.35–1.10 | .31 |

| Gregg et al., 2007 | Low-SES | ACT | Active (Diabetes Ed) | 73 | 5 | .57 | .12–1.01 | .31 |

| Hayes et al., 2004a | Low-SES | ACT | Active (12-step) | 56 | 9 | .21 | -.33–.74 | .45 |

| Hinton et al., 2004b | Vietnamese refugees | CA- CBT† | WL | 12 | 6 | 2.75 | 1.15–4.36 | <.01 |

| Hinton et al., 2005b | Cambodian refugees | CA-CBT † | WL | 40 | 7 | 3.26 | 2.32–4.21 | <.01 |

| Hinton et al., 2009 | Cambodian refugees | CA-CBT † | WL | 24 | 5 | 2.61 | 1.52–3.69 | <.01 |

| Hinton et al., 2011 | Latina women | CA-CBT † | Active (Applied Muscle Relaxation) | 24 | 2 | 1.54 | .65–2.43 | <.01 |

| James et al., 2011e | Underserved Adolescents | DBT‡ | Pre-Post | 18 | 4 | .74 | .31–1.16 | <.01 |

| Lundgren et al., 2006 | S. Africa | ACT | Active (Supportive Therapy) | 27 | 4 | 1.46 | .63–2.29 | <.01 |

| Lundgren et al., 2008 | India | ACT | Active (Yoga) | 18 | 3 | .82 | -.12–1.77 | .09 |

| Lynch et al., 2003 | Older Adults (85% White) | DBT | Active (Medication); DBT+MED vs. MED | 31 | 8 | .29 | -.48–1.05 | .46 |

| Lynch et al., 2007 (study 1) | Older Adults (88% White) | DBT | Active (Medication); DBT+MED vs. MED | 33 | 1 | .54 | -.29–1.38 | .20 |

| Lynch et al., 2007 (study 1) | Older Adults (86% White) | DBT | Active (Medication); DBT+MED vs. MED | 31 | 1 | .88 | .15–1.61 | .02 |

| Mendelson et al., 2010 | Urban Youth | Mindfulness + Yoga | No-Contact | 97 | 13 | .26 | -.18–.69 | .25 |

| Miller et al., 2000 | 92% minority | DBT | Pre-Post | 27 | 1 | .82 | .46–1.18 | b.01 |

| Morone et al., 2008 | Older Adults (89% White) | MBSR | WL | 37 | 8 | .32 | -.40–1.03 | .38 |

| Pasieczny and Connor, 2011 | Inner City Adults (Australia) | DBT | DBT vs. TAU | 84 | 10 | .82 | .25–1.39 | <.01 |

| Rathus and Miller, 2002c | 84% minority | DBT | DBT vs. TAU / Pre-Post | 67 | 6 | .37 | -.27–1.02 | .26 |

| Roth and Robbins, 2004 | Hispanic | MBSR | No Contact | 86 | 4 | .67 | .15–1.20 | .01 |

| Saavedra, 2008 | Community | ACT | WL | 26 | 3 | .73 | -.06–1.51 | .07 |

| Sakdalan et al., 2010 | Forensic with Intellectual Disability | DBT Skills Training | Pre-Post | 6 | 4 | .76 | .07–1.45 | .03 |

| Samuelson et al., 2007 | Forensic | MBSR | Pre-Post | 955 | 3 | .10 | .05–.15 | <.01 |

| Semple et al., 2010e,f | Inner City Youth | MBCT-C | Pre-Post | 20 | 3 | .43 | .08–.78 | .02 |

| Splevins et al., 2009 | Older Adults(Race/ethnicity not reported) | MBCT | Pre-Post | 22 | 4 | .57 | .28–.85 | <.01 |

| Trupin et al., 2002 | Forensic | DBT | DBT vs. TAU | 90 | 1 | .21 | -.20–.62 | .32 |

| Wetherell et al., 2010g | Older Adult | ACT | Pre-Post | 7 | 4 | .68 | .10–1.25 | .02 |

| Woodberry and Popenoe, 2008d | Community | DBT | Pre-Post | 28 | 13 | .40 | .07–.73 | .02 |

| Young and Baime, 2010 | Older Adult | MBSR | Pre-Post | 141 | 1 | .82 | .67–.97 | <.01 |

Note. TX=Treatment type stated by the author(s) or derivation thereof: ACT=Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; DBT=Dialectical Behavior Therapy; MBCT=Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy; MBCT-C=Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children; MBSR=Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction. N refers to the number of participants which a study reported that completed the post-treatment assessments and thus were included in the present analyses. In situations where N differed among study measures, we used the highest value. Number of Outcomes refers to a study's outcome variables that were used to compute the effect size. Hedges' g is the effect size estimate reported; .2=small effect, .5=medium effect, and .8=large effect.

Effect size was computed by comparing only the active treatment conditions in the study.

Effect size was computed by comparing the treatment to the waitlist condition before participants in the waitlist condition received treatment.

Authors reported posttreatment assessments were not administered for the control group, thus for some outcome measures, effect size estimates for between-subjects comparisons were unable to be conducted; instead we used pre-post within-treatment group differences to estimate the effect size.

Child and parent ratings were combined to produce an overall effect size for the study.

Only significant results were reported in this study, thus the overall effect size presented is likely an overestimation.

Effect size was computed by comparing the pre- to posttreatment change in study measures.

Although this study was an RCT comparing ACT to CBT, the effect size was computed by comparing the pre- to posttreatment change for the ACT treatment group given the small sample size and rate of attrition in the CBT condition.

CA-CBT is an integrative treatment that includes mindfulness principles with traditional CBT principles.

Treatment was described as DBT, but integrated with other techniques including CBT, psychodynamic, client-centered, Gestalt, paradoxical, and strategic approaches during the individual sessions.

Data analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 2.0 (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2005). When effect sizes were not provided, Cohen's d, reflecting the standardized mean difference, was calculated for all outcomes in each study reviewed. Next, an estimation for Hedges' g (Hedges, 1981) was applied as a conservative measure to correct for sample size. Although in most cases the difference between Cohen's d and Hedges' g is negligible, Cohen's d has been shown to have a slight bias and to overestimate the size of the effect, particularly in situations where the sample size is small (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009). For noncontrolled studies, or studies where control data were not provided, the mean difference from pre- to posttreatment was calculated and divided by the pooled standard deviation and subsequently estimated to Hedges' g. In calculating pre-to posttreatment effect sizes we used a global correction of r=.7 (Rosenthal, 1991) applied to study outcome measures. Finally, as we were interested in examining the general salutary effects of acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments, study outcomes were combined so that each study contributed one composite effect size indicating an overall benefit of treatment. The summary effect was then calculated using a random effects model based on study design.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive data for the studies that were included the meta-analysis. The results showed small to large effect sizes (Hedges' g range=.38 to 1.32; where .2 is a small effect, .5 is a medium effect, and .8 is a large effect). Studies that included no-contact or waitlist condition (k=7), on average, demonstrated the largest effect size (g=1.32), followed by studies that used an active treatment (k=9, g=.67) and studies using a pre-post design (k=11, g=.57). Studies comparing an acceptance- or mindfulness-based treatment to treatment as usual demonstrated the smallest effect sizes on average (k=5, g=.38) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Mean Effect Size by Study Type.

| Study Type | k | N | g | 95%-CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Post a | 11 | 1,234 | .57 | >.31–.82 | <.01 |

| No-Contact/Waitlist | 7 | 331 | 1.32 | >.61–2.02 | <.01 |

| Treatment as Usual a | 5 | 307 | .38 | >.11–.64 | .01 |

| Active Treatment | 9 | 327 | .67 | >.38–.96 | <.01 |

| Overall | 32 | 2,198 | .69 | >.51–.87 | <.01 |

Note. Hedges' g is the effect size estimate reported; .2=small effect, .5=medium effect, and .8=large effect.

Rathus and Miller (2003) was coded twice (Pre-Post and TAU) as only partial data were reported for between-subject effects and within-subject effects as outcome measures were not administered to control group at posttreatment.

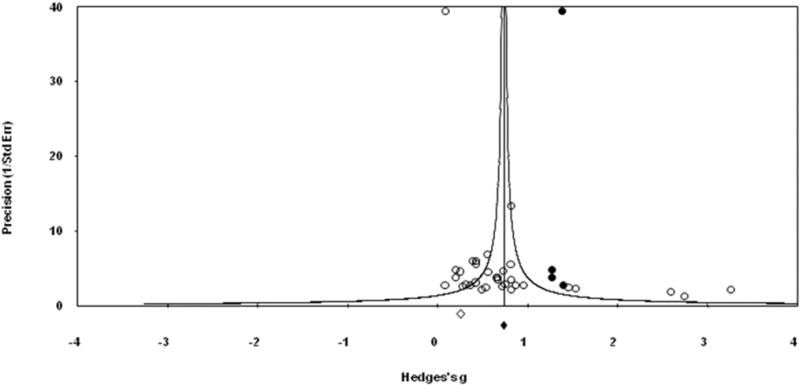

To assess for publication bias, we aggregated the studies and examined the overall effect size (g=.69). First, we calculated Rosenthal's fail-safe N (1979), for the number of studies that would be required to nullify the results of the present analysis. The fail-safe N was 1,986 studies (observed studies z=15.32, p<.001). Trim and fill method (Duval & Tweedie, 2000) was used as a secondary assessment of publication bias. The trim and fill method accounts for those studies with small sample size and extreme effect sizes by removing (i.e., trimming) them through an iterative procedure, and recomputing the effect size at each iteration until the funnel plot increases in symmetry. The trimmed studies are then reinserted (i.e., filled) with mirror images for each back into the analyses to correct for the reduction in variance from the process of removing the studies. The results indicated that removing the asymmetric studies (n=4) had minimal effect on the overall treatment effect size (Trim and Fill Adjusted g=.81, 95% CI [.55 − 1.07]), suggesting an absence of publication bias (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Funnel plot of precision by Hedges' g with studies imputed using the trim and fill method (n=4), suggesting absence of publication bias. Studies included the meta-analysis are indicated by open circles. Imputed studies are indicated by darkened circles. Hedges' g for the present analyses are indicated by open diamond. Adjusted effect size and standard error is indicated by darkened diamond.

Discussion

While these initial findings provide some promising support for the utility of acceptance and mindfulness-based treatments with people from diverse, underserved backgrounds, more rigorous clinical research is needed. The median number of participants in each study included in the meta-analysis was n=28, suggesting the need for studies with increased power. Also, relatively few studies included information on the theoretical rationale or considerations in adapting the treatment for a specific demographic group. A theory-driven approach to the adaptation of acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments could be helpful for bridging the gap between science and practice, as well as dissemination of treatment to practicing clinicians.

Lau (2006) suggests a selective and directive approach to the adaptation of evidence-based treatments for particular communities. The approach is selective in that adaptations are indicated when there is evidence to suggest that there is a clinical problem that occurs in the context of sociocultural factors within a particular community and the standard treatment component or approach does not sufficiently attend to these contextually specific risk factors that may be maintaining the problem behavior. The approach is directive in that it relies on data to inform the adaptations. This approach discourages unnecessary adaptations that threaten the fidelity of the evidence-based treatment. We are currently collecting qualitative data from clients of different ethnic backgrounds in order to obtain some preliminary information on the perceived appropriateness and cultural relevance of an ABBT for GAD that we hope will direct future research efforts on selective adaptations that may be needed.

Overview of the Special Series

In the articles that follow, researchers and clinicians present specific suggestions of how acceptance- and mindfulness-based behavioral treatments might be used with clients from nondominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds to optimize relevance and engagement. We invited submissions from clinicians and researchers working with a rrange of underserved populations to provide their clinical recommendations regarding the use of acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments with the specific populations and treatment settings with which they have experience. Although many important populations are also left out of this series, we believe that this represents an important first step towards understanding the ways in which these treatments already attend to important cultural mechanisms and areas in which adaptations need to be made in order for the treatments to be delivered in a more culturally competent manner.

Through the use of clinical examples, Rucker and West (2013-this issue) present some of the challenges that clinicians might encounter when delivering mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral treatments with individuals from underserved and underrepresented backgrounds in community settings. The authors offer suggestions for ways to address these challenges.

Dutton, Bermudez, Matas, Majid, and Myers (2013-this issue) present the results of a pilot study examining the use of MBSR as a community-based intervention for low-income, predominantly African American women with a history of intimate partner violence and PTSD. Treatment components and techniques that enhanced treatment feasibility and acceptability in this population are highlighted.

Hinton, Pich, Hofmann, and Otto (2013-this issue) describe how acceptance and mindfulness techniques are utilized in a culturally adapted cognitive behavior therapy targeting the experiences of refugees and ethnic minority populations with PTSD. Through the use of case examples, the ways that acceptance and mindfulness techniques are delivered with Latino/a and Southeast Asian refugee populations with PTSD are illustrated.

Petkus and Wetherell (2013-this issue) provide a theoretical and research-based rationale for using ACT with older adults and describe specific treatment considerations to increase engagement and response when using ACT with older adults.

Finally, Dimidjian and Kleiber (2013-this issue) and La Roche and Lustig (2013-this issue) provide commentaries on the series, including discussion of clinical implications and future directions for research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the members of the ACT and Mindfulness communities for responding to our solicitations to share their work and resources with us for inclusion in this review. Although not all contributions solicited were included in this paper, we would like to thank Sarah Bowen, Helen Coelho, Devon Hinton, Brjánn Ljótsson, Jonathan Kanter, Marco Kleen, Nancy Kocovski, David Neale-Lorello, and Katherine Rimes for responding to our requests.

Footnotes

Cara Fuchs is now at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior and Jonathan K. Lee is now at the Family Institute at Northwestern University.

References included the meta-analysis are noted by an asterisk.

Contributor Information

Cara Fuchs, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Jonathan K. Lee, Suffolk University

Lizabeth Roemer, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Susan M. Orsillo, Suffolk University

References1

- Bach P, Hayes SC. The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1129–1139. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Fischer S, Huss DB. Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of disordered eating. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:281–300. doi: 10.1007/s10942-005-0015-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barona A, Santos de Barona M. Council of National Psychological Associations for the Advancement of Ethnic Minority Interests. Psychological treatment of ethnic minority populations. Washington DC: Association of Black Psychologists; 2003. Recommendations for the psychological treatment of Latino/Hispanics populations. Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/pi/oema/resources/brochures/treatment-minority.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:279–289. doi: 10.1037/a0023626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer ET, Fledderus M, Rokx TAJJ, Pieterse ME. Efficacy of an early intervention based on acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with depressive symptomatology: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2005. Version 2. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, Witkiewitz K, Hsu S, Grow J, et al. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A pilot efficacy trial. Substance Abuse. 2009;30(4):295–305. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Dillworth TM, Chawla N, Simpson TL, Ostafin BD, Marlatt G. Mindfulness meditation and substance use in an incarcerated population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:343–347. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bradley RG, Follingstad DR. Group therapy for incarcerated women who experienced interpersonal violence: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:337–340. doi: 10.1023/A:1024409817437. 10.1023/A: 1024409817437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz L. Latino healing: The integration of ethnic psychology into psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43:436–453. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Comtois KA, Elwood L, Holdcraft LC, Smith WR, Simpson TL. Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy in a community mental health center. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Koeske G, Rosen D, ReynoldsIII CF, Braun C. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: The impact of stigma and race. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:531–543. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J, Wilson KG, Luciano C, Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Kleiber B. Being Mindful About the Use of Mindfulness in Clinical Contexts. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):57–59. this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Bermudez D, Matas A, Majid H, Mylers NL. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Low-Income, Predominantly African American Women With PTSD and a History of Intimate Partner Violence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.08.003. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot– based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-snalysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2676988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein BA, Northrop LE, MacDonald LM. Assessment. In: Rosowsky E, Casciani JM, Arnold M, editors. Geropsychology and long term care: A practitioner's guide. New York: Springer Science + Business Media; 2009. pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Mihalic S. Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prevention Science. 2004;5:47–52. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013981.28071.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Evershed S, Tennant A, Boomer D, Rees A, Barkham M, Watson A. Practice-based outcomes of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) targeting anger and violence, with male forensic patients: A pragmatic and non-contemporaneous comparison. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2003;13:198–213. doi: 10.1002/cbm.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Boettiger CA, Howard MO. Mindfulness training modifies cognitive, affective, and physiological mechanisms implicated in alcohol dependence: Results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42:177–192. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD. Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pilot results. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:415–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:336–343. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:639–665. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- *.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Bissett R, Piasecki M, Batten SV, Gregg J. A preliminary trial of Twelve-Step Facilitation and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with polysubstance-abusing methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:667–688. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80014-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA. Addressing cultural complexities in practice: Assessment, diagnosis, and therapy. 2nd. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA. Integrating evidence-based practice, cognitive-behavior therapy, and multicultural therapy: Ten steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:354–360. doi: 10.1037/a0016250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1981;6:107–128. doi: 10.3102/10769986006002107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Talleyrand RM. Race is not ethnicity. American Psychologist. 1997;52:1246–1247. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.11.1246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Safren SA, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A cross-over design. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:617–629. doi: 10.1002/jts.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH, Otto MW. Mechanisms of efficacy of CBT for Cambodian refugees with PTSD: Improvement in emotion regulation and orthostatic blood pressure response. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2009;15:255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Rivera E, Otto MW, Pollack MH. Culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT) for Latino women with treatment-resistant PTSD: A pilot study comparing CA-CBT to applied muscle relaxation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hinton DE, Pham T, Tran M, Safren SA, Otto MW, Pollack MH. CBT for Vietnamese refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:429–433. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048956.03529.fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Hofmann SG, Otto MW. Acceptance and Mindfulness Techniques as Applied to Refugee and Ethnic Minority Populations With PTSD: Examples From ″Culturally Adapted CBT″. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):33–46. this issue. [Google Scholar]

- *.James AC, Winmill L, Anderson C, Alfoadari K. A preliminary study of an extension of a community dialectic behaviour therapy (DBT) programme to adolescents in the Looked After Care system. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2011;16:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Bantam Dell; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) Constructivism in the Human Sciences. 2003;8(2):73–107. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&=2010-06382-006&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. New York: Hyperion; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- La Roche MJ, Lustig K. Being Mindful About the Assessment of Culture: A Cultural Analysis of Culturally Adapted Acceptance-Based Behavior Therapy Approaches. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):60–63. this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Fuchs C, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Cultural considerations inacceptance-based behavior therapy. In: Roemer L, Orsillo SM, editors. Mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral therapies in practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Liehr P, Diaz N. A pilot study examining the effect of mindfulness on depression and anxiety for minority children. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;24:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- *.Lundgren T, Dahl J, Melin L, Kies B. Evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy for drug refractory epilepsy: A randomized controlled trial inSouth Africa—A pilot study. Epilepsia. 2006;47(12):2173–2179. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lundgren T, Dahl J, Yardi N, Melin L. Acceptance and commitment therapy and yoga for drug-refractory epilepsy: A randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2008;13:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lynch TR, Cheavens JS, Cukrowicz KC, Thorp SR, Bronner L, Beyer J. Treatment of older adults with co-morbid personality disorder and depression: A dialectical behavior therapy approach. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:131–143. doi: 10.1002/gps.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lynch TR, Morse JQ, Mendelson T, Robins CJ. Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: A randomized pilot study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:33–45. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.11.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA. Buddhist philosophy and the treatment of addictive behavior. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2002;9:44–49. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(02)80039-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mendelson T, Greenberg MT, Dariotis JK, Gould LF, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Miller AL, Wyman SE, Huppert JD, Glassman SL, Rathus JH. Analysis of behavioral skills utilized by suicidal adolescents receiving dialectical behavior therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:183–187. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(00)80029-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Morone NE, Greco CM, Weiner DK. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. Pain. 2008;134:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama Hall GC. Introduction to the special section on multicultural and community psychology: Clinical psychology in context. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:787–789. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsillo SM, Roemer L. Acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches to anxiety: Conceptualization and treatment. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- *.Pasieczny N, Connor J. The effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy in routine public mental health settings: An Australian controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen PB, Ivey AE. Culture-centered counseling and interviewing skills: A practical guide. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Petkus AJ, Wetherell JL. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy With Older Adults: Rationale and Considerations. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.07.004. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rathus JH, Miller AL. Dialectical Behavior Therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2002;32:146–157. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Mindfulness- and acceptance-based behavioral therapies in practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:638–641. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Rev. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- *.Roth B, Robbins D. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health-related quality of life: Findings from a bilingual innercity patient population. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:113–123. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000097337.00754.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker L, West L. Clinical Considerations in Using Mindfulness- and Acceptance-Based Approaches With Diverse Populations: Addressing Challenges in Service Delivery in Diverse Community Settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1):13–22. this issue. [Google Scholar]

- *.Saavedra KB. Toward a new Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) treatment of problematic anger for low income minorities in substance abuse recovery: A randomized controlled experiment. Vol. 69. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2008. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2008-99180-134&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- Sakdalan JA, Shaw J, Collier V. Staying in the here-and-now: A pilot study on the use of dialectical behaviour therapy group skills training for forensic clients with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2010;54:568–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Samuelson M, Carmody J, Kabat-Zinn J, Bratt MA. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in Massachusetts correctional facilities. The Prison Journal. 2007;87:254–268. doi: 10.1177/0032885507303753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- *.Semple RJ, Lee J, Rosa D, Miller LF. A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:218–229. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9301-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Splevins K, Smith A, Simpson J. Do improvements in emotional distress correlate with becoming more mindful? A study of older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13:328–335. doi: 10.1080/13607860802459807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Sue D. Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice. 4th. Hoboken: John Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. In search of cultural competence in psychotherapy and counseling. American Psychologist. 1998;53:440–448. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Cultural competency: From philosophy to research and practice. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:237–245. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Trupin EW, Stewart DG, Beach B, Boesky L. Effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy program for incarcerated female juvenile offenders. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2002;7:121–127. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. An older and more diverse nation by mid-century (Report CB08-123) Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2008. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report (Publication No.11-0005) Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr10.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The next four decades: The holder population in the United States: 2010–2050 (Report P25-138) Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- *.Wetherell JL, Liu L, Patterson TL, Afari N, Ayers CR, Thorp SR, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: A preliminary report. Behavior Therapy. 2010;42:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Alatiq Y, Crane C, Barnhofer T, Fennell MJV, Duggan DS, Goodwin GM. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in bipolar disorder: Preliminary evaluation of immediate effects on between-episode functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;107(1–3):275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Woodberry KA, Popenoe EJ. Implementing dialectical behavior therapy with adolescents and their families in a community outpatient clinic. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2008;15:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2007.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Young LA, Baime MJ. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: Effect on emotional distress in older adults. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2010;15:59–64. doi: 10.1177/1533210110387687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]