Abstract

Patient: Male, 49

Final Diagnosis: BK nephropathy without detectable viremia or viruria

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Kidney biopsy

Specialty: Nephrology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

BK nephropathy is an evolving challenge among kidney transplant recipients. Diagnosis of BK nephropathy depends on the presence of BK viral inclusions on renal biopsy. Most cases of BK nephropathy are preceded by BK viremia or viruria.

Case Report:

We report a case of BK nephropathy found on protocol renal transplant biopsy without associated BK viremia or viruria.

Conclusions:

BK nephropathy may occur even in the absence of BK viremia or viruria. Protocol biopsy is a useful tool to detect these cases.

MeSH Keywords: BK Virus, Kidney Transplantation, Viremia

Background

BK nephropathy is an evolving challenge among kidney transplant recipients. The degree of immunosuppression is probably the most important risk factor underlying BK viral infection. A definitive diagnosis of BK nephropathy is based on the presence of BK virus in tissue obtained by kidney biopsy. A presumptive diagnosis may be made by the demonstration of BK replication in plasma by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in the absence or presence of kidney dysfunction. Most cases of BK nephropathy are preceded by BK viruria followed by viremia. Here, we report the first case of BK nephropathy with no evidence of BK viremia and viruria

Case Report

We present the case of a 49-year-old male patient who had end-stage renal disease due to IgA nephropathy, on peritoneal dialysis for 4 months, and who subsequently underwent kidney transplantation from a living unrelated donor in August 2012. The patient received basiliximab induction therapy and was maintained on a regimen of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He had an unremarkable post-transplant course. His serum creatinine was stable at 1.4–1.6 mg/dl for the past 2 years.

The patient was seen at the transplant clinic for routine follow-up and 2-year protocol biopsy. At that time, he was taking tacrolimus 4 mg twice daily, mycophenolate mofetil 750 mg twice daily, and prednisone 5 mg once daily. He was asymptomatic and had stable vital signs. His physical exam was unremarkable.

His renal allograft on the right lower quadrant had no bruit. His labs showed white blood cell count of 5500/ml, hemoglobin of 14.2 g/dl, and platelet count of 149 000/ml. His serum electrolytes were within acceptable range. His serum creatinine was 1.6 mg/dl, which was within his usual range as shown in Table 1. The patient had no detectable antibodies to human leukocyte antigen.

Table 1.

Serum and urine laboratory values at admission.

| Labs | Value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| WbC, K/mL | 5.5 | 3.4–10.4 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.2 | 11.5–15.5 |

| Platelet, K/mL | 149 | 150–425 |

| Sodium, mMol/L | 139 | 136–145 |

| Potassium, mMol/L | 4.3 | 3.5–5.1 |

| Chloride, mMol/L | 108 | 101–111 |

| CO2, mMol/L | 27 | 23–25 |

| BUN,mg/dl | 30 | 7–20 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.6 | 0.6–1.1 |

| Calcium, mg/dl | 9.9 | 8.6–10.6 |

| Phosphorous, mg/dl | 2.6 | 2.3–4.7 |

| Urine analysis | PH: 5.5, WBC: 1, RBC: 3, protein: negative |

WBC – white blood cell; BUN – blood urea nitrogen.

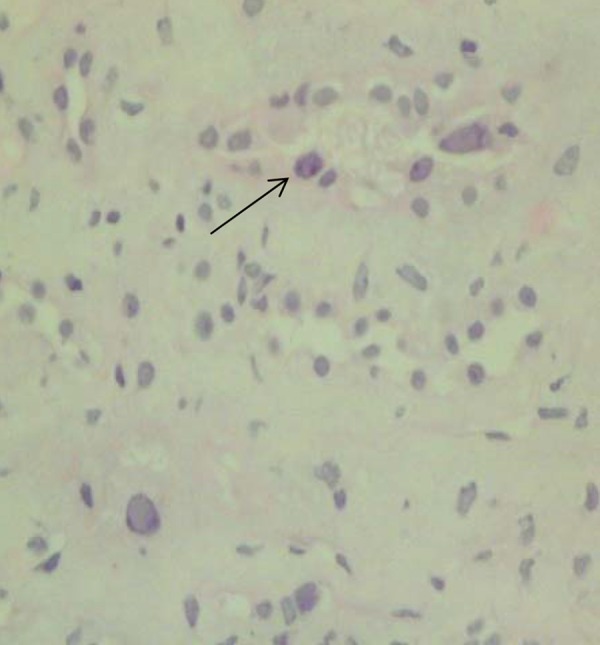

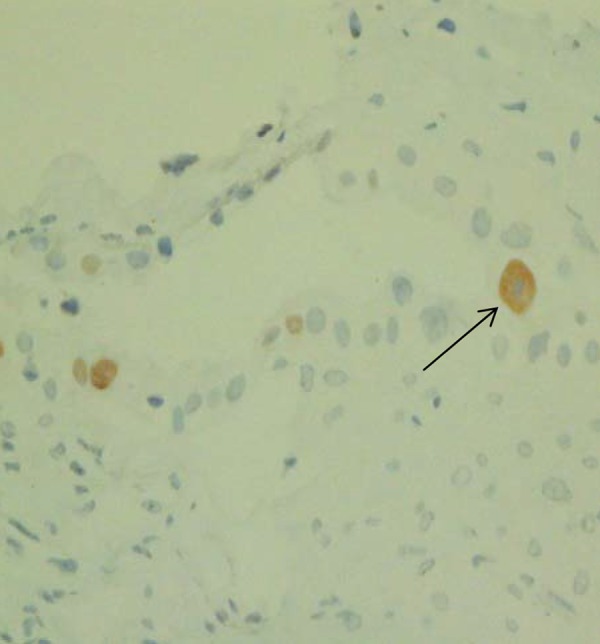

The patient’s kidney biopsy result is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing intranuclear viral inclusions.

Figure 2.

Simian virus 40 stain consistent with BK nephropathy.

Retrospectively, BK PCR in the blood was repeated and remained negative. BK virus PCR in the urine was sent and came back negative. JC virus PCR was also negative. Urine cytology demonstrated the presence of decoy cells.

Discussion

Performing protocol allograft biopsies at fixed time points has led to a better understanding of graft injury and has been proven to be useful for detecting unexpected pathology in well-functioning allografts. Subclinical acute rejection, subclinical peritubular capillaritis, viral nephropathies, and early transplant glomerulopathy have been recognized on protocol kidney biopsies [1–3]. The early recognition of these histological changes may therefore result in optimization of the immunosuppressive regimen and subsequent improvement in both short- and long-term allograft survival.

Polyomavirus infection is recognized as an important cause of renal allograft dysfunction. BK-induced nephropathy reportedly occurs in up to 10% of kidney allograft recipients and causes allograft failure in approximately 15–50% of affected individuals [4].

Polyomaviruses are small (45 nm, approximately 5000 base pairs), DNA-containing viruses, and include 3 closely related viruses of clinical significance: Simian virus 40 (SV-40), JC virus (JCV), and BK virus (BKV). SV-40 naturally infects rhesus monkeys but can infect humans, while BKV and JCV cause productive infection only in humans. Acquisition of BKV begins in infancy. Serological evidence of infection by BKV is present in 37% of individuals by 5 years of age and over 80% of adolescents. After natural viral transmission during childhood, BKV is known to persist in the reno-urinary tract with intermittent reactivation and low-level viruria in 5–10% of immunocompetent adults [5]. Among immunocompromised individuals, the frequency of BK virus infection increases to 20–60%, and large viruria often with the appearance of decoy cells is common.

BK viral infections progress through well-characterized stages [6]. With progressive infection, BK viral DNA is first detected in the urine, followed by detection in the plasma, and, finally, in the renal parenchyma. The most specific surrogate markers of renal parenchymal involvement with BK are persistent viruria (≥107 copies/mL) and increasing viremia (≥104 copies/mL) for more than 3 weeks, independent of renal function [7]. Surveillance protocol biopsies allow for detection of invasive BK viral disease at a subclinical stage and, importantly, this early diagnosis is accompanied by reduced risk of subsequent disease progression [8].

Most cases of clinically significant nephropathy are preceded by a period of asymptomatic viruria followed by viremia [9]. Viruria and viremia may be detected weeks to months before there is a detectable increase in the serum creatinine, suggesting that routine screening and preemptive treatment may be an effective strategy among transplant recipients. Asymptomatic urinary viral shedding is followed by early graft invasion with detectable viremia and, subsequently, by clinical graft dysfunction with overt histologic disease. Consistent with this model, there is evidence for a predictable histologic sequence in polyoma virus-associated nephropathy (PVAN), with the earliest stage consisting of cytopathic changes within clusters of medullary tubular epithelial cells.

Nickeleit et al. [10] have suggested that urine cytology can be used as a first-line screening test to identify individuals requiring further monitoring. Ding et al. [11] have reported that sequential quantitative PCR of urine may identify a “threshold viral load” for predicting the occurrence of PVAN. Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of BKV in blood samples by PCR at the time of histological diagnosis of PVAN [12]. These reports clearly showed that detectable BKV in blood predate the development of histologic PVAN and that reduction in immunosuppression can be rapidly followed by disappearance of virus from the blood.

Limaye et al. [13] reported BKVN in an immunosuppressed non-renal transplant patient without detectable viremia. However, BK nephropathy in renal transplant without detectable viremia has not been reported. Here, we report the first case of BK nephropathy in a renal transplant patient with no evidence of BK viremia. The exact reason for this clinical scenario is unclear, and possibilities include non-standardization of BKV DNA estimation leading to variability in levels of detectable viremia among laboratory assays. Thus, one should be cautious in recommending a level of viremia as a threshold for the occurrence of nephropathy.

BK virus has been divided into 4 serological groups (I to IV) and genotypes, which may have different strengths of virulence. Serum BK virus PCR may not detect all serotypes and thus negative PCR may lead to false-negative results. As SV-40 stain may detect both BK virus and JC virus, we sent for JC virus PCR, which came back negative. We concluded that this patient has histological evidence of BK nephropathy without detectable BK in urine and blood PCR.

We decreased our patient’s mycophenolate mofetil dose from 750 mg twice daily to 500 mg twice daily and we decreased his tacrolimus level target to 4–6 ng/ml.

We decided to follow up his BK nephropathy by monthly follow-up of his kidney function test and his blood BK virus PCR. His kidney function remains stable at his baseline and his monthly blood BK virus PCR remains negative.

At some point, it may be warranted to repeat the kidney biopsy to see if the histologic changes of BK nephropathy have been resolved after we reduced his immunosuppression.

Conclusions

BK nephropathy may occur even in the absence of BK viremia or viruria. In these cases, surveillance protocol biopsy proves useful in the early detection of BK nephropathy and subsequent management before renal dysfunction sets in.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. There was no financial support or funding for this manuscript.

References:

- 1.Rush DN, Henry SF, Jeffery JR, et al. Histological findings in early routine biopsies of stable renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1994;57(2):208–11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199401001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro R, Randhawa P, Jordan ML, et al. An analysis of early renal transplant protocol biopsies – the high incidence of subclinical tubulitis. Am J Transplant. 2001;1(1):47–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.010109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legendre C, Thervet E, Skhiri H, et al. Histologic features of chronic allograft nephropathy revealed by protocol biopsies in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1998;65(11):1506–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199806150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch HH. Polyomavirus BK nephropathy: A (re-)emerging complication in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:25–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polo C, Perez JL, Mielnichuck A, et al. Prevalence and patterns of polyomavirus urinary excretion in immunocompetent adults and children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:640–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch HH, Knowles W, Dickenmann M, et al. Prospective study of polyomavirus type BK replication and nephropathy in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:488–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randhawa P, Ho A, Shapiro R, et al. Correlates of quantitative measurement of BK polyomavirus (BKV) DNA with clinical course of BKV infection in renal transplant patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1176–80. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1176-1180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buehrig CK, Lager DJ, Stegall MD, et al. Influence of surveillance renal allograft biopsy on diagnosis and prognosis of polyomavirusassociated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64:665–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randhawa P, Brennan DC. BK virus infection in transplant recipients: an overview and update. Am J Transplantm. 2006;6:2000–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickeleit V, Hirsch HH, Binet IF, et al. Polyomavirus infection of renal allograft recipients: From latent infection to manifest disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(5):1080–89. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1051080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding R, Medeiros M, Dadhania D, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of BK virus nephritis by measurement of messenger RNA for BK virus VP1 in urine. Transplantation. 2002;74:987–94. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC. Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy: update in diagnosis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006;8(2):68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limaye AP, Smith KD, Cook L, et al. Polyoma virus nephropathy in native kidneys of non renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:614–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]