Abstract

Several recent United States (US) policies target spatial access to healthier food retailers. We evaluated two measures of community food access developed by two different agencies, using a 2009 food environment validation study in South Carolina as a reference. While the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service’s (USDA ERS) measure designated 22.5% of census tracts as food deserts, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) measure designated 29.0% as non-healthier retail tracts; 71% of tracts were designated consistently between USDA ERS and CDC. Our findings suggest a need for greater harmonization of these measures of community food access.

Keywords: spatial access, food environment, food desert, policy

INTRODUCTION

Improving spatial access to healthy food retailers has emerged as a novel approach in public policy in the United States (US), complementing long-standing policies on economic food access.1, 2 Three federal agencies joined forces to improve access to healthy and affordable foods in the context of the Healthy Food Financing Initiative of 2010, namely the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the US Department of Treasury.1 In conjunction with these efforts, several spatial measures of community food access were developed for purposes ranging from surveillance to policy implementation.1, 3–7 For instance, the USDA Economic Research Service (USDA ERS) developed a definition for food deserts which was embedded in the USDA Food Desert Locator in 2009.4 This has recently been updated in the Food Access Research Atlas in March 2013.5, 8 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported on tracts with healthier food retailers in the context of their State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables in 2009 and 2013.7, 9

The issue of poor access to healthy and affordable foods reached national prominence when the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (generally known as the 2008 Farm Bill) directed USDA to conduct a study of food deserts.10 The 2008 Farm Bill defined a food desert as “an area in the United States with limited access to affordable and nutritious food, particularly such an area composed of predominantly lower income neighborhoods and communities”.11 The USDA ERS subsequently identified 8,894 food desert census tracts (i.e. about 12% of a total of 72,365) in the continental US in 2013 as low income tracts in which residents had poor access to healthier food retailers.8 In parallel, the CDC reported that in 2013, 70% of census tracts were considered healthier food retail tracts because they contained at least one supermarket or large grocery store.7 The marked difference between the 30% of tracts considered non-healthier food retail tracts by the CDC and the roughly 12% considered food deserts by USDA ERS raises questions. A brief comparison of the published methodologies of these two measures of community food access reveals that they are based on very different criteria, methods and secondary data sources listing retail food outlets. An empirical evaluation of the how much of the differences in designations of areas as having poor food access is driven by the differences between the methodologies would be informative to policy makers and community health practitioners. To the best of our knowledge, these two measures of community food access have not been compared systematically.

One approach to a systematic evaluation would be to use a single, high-quality data source on food retail outlets, replicate the measures according to each agency’s criteria, and compare the results. We had the opportunity to conduct such an evaluation based on data from an eight-county food environment validation study that had verified the exact geospatial location and confirmed the outlet type of each food outlet in the area.12 Thus, the purpose of this project was twofold: (1) To replicate the USDA ERS’s food desert measure and the CDC’s healthier food retail tracts measure using a single, validated data source of the food environment; and (2) To compare the two measures with respect to the areas identified as having poor food retail access and the size of populations living in these areas.

METHODS

Study Area and Food Environment Data

We utilized data of a field census (i.e. on the ground verification) of retail food outlets conducted in 2009.12, 13 The food environment data included geospatial information and store type attributes on all retail food outlets located in seven rural counties (Chester, Lancaster, Fairfield, Kershaw, Calhoun, Clarendon, and Orangeburg) and one urban county (Richland) in South Carolina (Figure 1). Of the 2,208 food outlets situated within the boundaries of the 169 census tracts in the study area, the locations of 108 food retail outlets (including supermarkets, supercenters, warehouse clubs, large grocery stores and fruit and vegetable markets, but excluding convenience stores, dollar stores, drug stores, farmer’s markets, and any other types of stores) were used for the replication of the two community food access measures. The types of food outlets were determined according to the definitions of the food access measures developed by the respective agencies.3, 7, 9, 14

Figure 1.

South Carolina Study Area

To account for stores that could lie just outside the boundary of our study area, a 10-mile external buffer (Euclidian distance) was constructed using existing but non-verified data from the South Carolina Department of Environmental Health and Control Licensed Food Services Facilities Database (a list of all licensed food services facilities in South Carolina) and from InfoUSA (a commercial business listing of food outlets), corresponding to the time period of the field census.12 An additional 92 grocery stores were contained within this buffer area, resulting in an overarching total for the study area plus buffer of 200 eligible outlets.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analyses

GIS-based methods and ArcGIS 10 software (Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) 2011, Redlands, CA) were used to replicate the two measures of community food access, using the food environment data described above. For network distance calculations street centerlines from Streetmap Premium (ESRI, 2011) based on commercial street centerline data from NAVTEQ and Tom Tom were used within the Network Analyst extension of ArcGIS.

USDA ERS Food Deserts

This measure was first introduced in 2009 with USDA ERS’ report to Congress3, 4 and has been updated in 2013.5, 8, 14 It designates areas as food deserts at the census tract level based on income and distance, identifying tracts that are low income in which residents have low access to a supermarket. The definition of supermarkets includes supercenters, warehouse clubs, and large grocery stores (defined as having 50 or more employees). A total of 102 outlets met these inclusion criteria and were located within in our study area. A tract was considered a food desert if 1) the tract met the US Treasury Department’s New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) program eligibility criteria and 2) 33% of tract population (or a minimum of 500 people) lived outside the threshold distance to the nearest supermarket (1 mile in urban areas or 10 miles in rural areas). For a tract to be eligible for the NMTC it had to have 1) a poverty rate of at least 20% or 2) a median family income less than 80% of the statewide median family income (for tracts not in metropolitan areas), or a median family income less than 80% of the metropolitan area median family income or less than 80% of the state median family income (for tracts in metropolitan areas).3, 5, 14, 15

Population and economic data were derived from the 0.5km × 0.5km gridded population estimates. Because income is a primary determining factor for the identification of food deserts, only tracts meeting the low income criteria were used in the GIS model. The polygonal 0.5km × 0.5km population grids were created to cover the study area and surrounding 10 mile buffer. Census 2010 block level population data were used to estimate the population within each grid cell by areal weighting. The population grids were converted to point data using a centroid approach retaining the census population estimates of all people living within each grid cell. Euclidean distance from each grid cell centroid to the nearest food outlet was calculated in miles. Distance results in conjunction with income, urbanicity, and population counts were used in ArcGIS to identify a tract as a food desert. Urbanicity was determined by the intersection of population- weighted tract centroids with 2010 Census Urban Areas (UA) and Urban Clusters (UC). A tract was considered “urban” if its population-weighted centroid fell within a UA or UC, otherwise the tract was considered to be “rural.” Population data points located in low income tracts that exceeded a threshold distance of 1 mile (urban) or 10 miles (rural) were summed within their corresponding tract boundary to obtain a total population of low access individuals.

CDC Non-Healthier Retail Tracts

We focused on the logical counterpart to the CDC’s healthier retail tract measure,7, 16 those census tracts which do not contain healthier food retailers. The definition of this measure has not changed between 2009 and 2013.7, 9 This measure designates a census tract as a non-healthier retail tract based on the lack of a healthier food retailer within a census tract or a half-mile outside of the tract. The definition of healthier food retailers included supercenters, warehouse clubs, large grocery stores (defined as having 50 or more employees) and fruit and vegetable markets which applied to a total of 200 food outlets in the study area plus 10-mile buffer. Counts of food outlets were determined using a spatial join between the census tract buffers and food outlets.

Sensitivity Analyses

We additionally conducted a limited set of sensitivity analyses in which we first modified the types of eligible food outlets (USDA ERS criteria vs. CDC criteria), and then subsequently added two modifications of the USDA ERS’s measure (removal solely of the low income criteria, followed by removal solely of the low access criteria) layered on top of the food outlet criteria, resulting in a total of 6 additional scenarios.

Urban versus Non-Urban Areas

In the present study, we define urban and non-urban residents using the 2010 Census-based designation of urban and rural areas.16 The urbanized areas (of 50,000 or more people) were considered as urban areas. Urban clusters (of at least 2,500 and less than 50,000 people) and rural areas were considered as non-urban areas in this study.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses included calculation of the percent of census tracts designated as meeting a given criteria. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated by approximating the binomial distribution with a normal distribution. Analyses were conducted using SAS software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

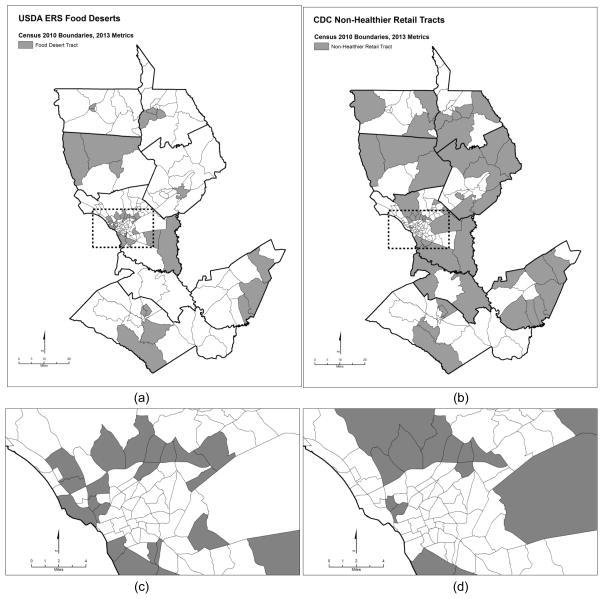

Areas identified as having poor access to healthier food retailers according to each of the two measures of community food access are shown in Figure 2. Panels a and b present the entire eight-county study area. Panels c and d focus on the largely urban area around the city of Columbia. Marked differences were observed in which census tracts were designated as having poor spatial food access.

Figure 2.

Geographic variation in two spatial measures of community food access: Entire South Carolina study area (panels a, b) and urban areas only (panels c, d)

The quantitative comparison between the two measures of community food access (Table 1) reveals that according to the USDA ERS, 38 (22.5%) of the 169 census tracts in the study area were designated as food deserts, compared to 49 (29.0%) tracts considered non-healthier retail tracts according to the CDC’s measure. The population estimated to be residing in areas with poor access to healthier foods ranged from 147,872 to more than 177,012. Large differences in the size of the areas were also observed, ranging from 1,155 square miles according to USDA ERS to 3,133 square miles according to CDC (see also Figure 2). The prevalence of areas with poor food access was somewhat more similar in urban areas (22.8% vs. 13.9%) of tracts designated as having poor food access by USDA ERS vs. CDC) than in non-urban areas (22.2% vs. 42.2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of South Carolina study area characterized by two spatial measures of community food access

| USDA ERS Food Desert Tracts (2013 Metric) | CDC Non-Healthier Retail Tracts (2013 Metric) | |

|---|---|---|

| Entire Study Area (169 Tracts) | ||

| Number of Poor Food Access Tracts | 38 | 49 |

| Percent (95% CI) | 22.5 (16.8, 29.4) | 29.0 (22.7, 36.2) |

| Resident Population (%) | 147,872 (20.5) | 177,012 (24.5) |

| Area in Square Miles (%) | 1,155 (20.7) | 3,133 (56.2) |

|

| ||

| Urban Study Area (79 Tracts) | ||

| Number of Poor Food Access Tracts | 18 | 11 |

| Percent (95% CI) | 22.8 (14.9, 33.2) | 13.9 (8.0, 23.2) |

| Resident Population (%) | 64,222 (19.2) | 36,709 (11.0) |

| Area in Square Miles (%) | 46 (20.2) | 35 (15.4) |

|

| ||

| Non-Urban Study Area (90 Tracts) | ||

| Number of Poor Food Access Tracts | 20 | 38 |

| Percent (95% CI) | 22.2 (14.9, 31.9) | 42.2 (32.5, 52.5) |

| Resident Population (%) | 83,650 (21.6) | 140,303 (36.2) |

| Area in Square Miles (%) | 1,108 (20.7) | 3,098 (57.9) |

All the estimates in the table are based on Census 2010 geographies.

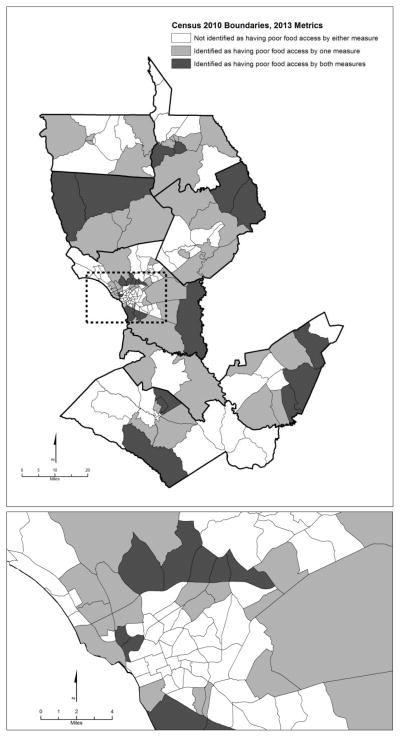

Approximately 71% of census tracts received an identical designation as being an area of poor food access (or not) by the two community food access measures (Table 2). Of the 169 census tracts, 1) 101 (59.8%) were not considered as having poor food access by both measures, 2) 19 tracts (11.2%) were identified by both measures as having poor food access, and 3) 49 (29.0%) were designated as having poor access by one but not the two measures. The consistency was markedly higher in urban areas (83.5%) than in non-urban areas (60.0%). Figure 3 visualizes these analyses on a map, indicating which areas were consistently identified by both measures of community food access or by only one measure.

Table 2.

Geographic agreement between two spatial measures of community food access

| USDA ERS Food Desert Tracts (2013 Metric) | CDC Non-Healthier Retail Tracts (2013 Metric)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Entire Study Area (169 Tracts) | ||

| Yes | 19 (11.2%) | 19 (11.2) |

| No | 30 (17.8%) | 101 (59.8%) |

|

| ||

| Urban Study Area (79 Tracts) | ||

| Yes | 8 (10.1%) | 10 (12.7%) |

| No | 3 (3.8%) | 58 (73.4%) |

|

| ||

| Non-Urban Study Area (90 Tracts) | ||

| Yes | 11 (12.2%) | 9 (10.0%) |

| No | 27(30.0%) | 43 (47.8%) |

All the estimates in the table are based on Census 2010 geographies.

Figure 3.

Geographic consistency between two spatial measures of community food access in South Carolina study area

Table 3 shows the results of sensitivity analyses conducted on the entire study area in which we first only modified the types of eligible food outlets (USDA ERS criteria vs. CDC criteria), and subsequently added two modifications of the USDA ERS’s measure, resulting in a total of 6 scenarios. Modifying the food outlet component of either measures did not have a large impact on the designation of tracts as areas of poor food access, nor on the level of consistency between the two measures, as shown by comparing Scenario 1 (original) with Scenario 2 and 3, and the latter two Scenarios to each other. The consistency between measures was fairly robust in the range of 71–78% of census tracts being designated identically (and 22–29% discordantly). However, removing either the low income criteria from the USDA ERS measure or the low access criteria, resulted in a substantial increase in inconsistencies between the two measures, with the percent of discordantly designated tracts ranging from 44–52%, depending on scenario. For instance, when in Scenario 4 the USDA ERS food desert measure was constructed using only the low access criteria (and both measures used the USDA ERS types of food outlets), 44% of tracts were discordantly assigned, compared to the 29% under the original agency-specific definitions of Scenario 1.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses of spatial measures of community food access: Impact of varying types of food outlets, income and access criteria on geographic agreement

| Designation of census tracts as having poor access: | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 | Scenario 6 | Scenario 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| By agencies’ definitions | Modifying food outlet component | Modifying food outlet component and income/access component | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Using USDA ERS’ list of food outlets for both metrics | Using CDC’s list of food outlets for both metrics | Using USDA ERS’ list of food outlets for both metrics & Income removed entirely from USDA ERS, no change to CDC | Using USDA ERS’ list of food outlets for both metrics & Access removed entirely from USDA ERS, no change to CDC | Using CDC’s list of food outlets for both metrics & Income removed entirely from USDA ERS, no change to CDC | Using CDC’s list of food outlets for both metrics & Access removed entirely from USDA ERS, no change to CDC | |||

| USDA ERS | CDC | |||||||

| Yes | Yes | 19 (11.2%) | 20 (11.8%) | 18(10.7%) | 29 (17.2%) | 34 (20.1%) | 28 (16.6%) | 31 (18.3%) |

| No | No | 101 (60.0%) | 101 (60%) | 101 (60%) | 66 (39.1%) | 52 (30.8%) | 67 (39.6%) | 50 (29.6%) |

| Yes | No | 19 (11.2%) | 18 (10.7%) | 19 (11.2%) | 53 (31.4%) | 67 (39.6%) | 53 (31.4%) | 70 (41.4%) |

| No | Yes | 30 (17.8%) | 30 (17.8%) | 31 (18.3%) | 21 (12.4%) | 16 (9.5%) | 21 (12.4%) | 18 (10.7%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Concordant tract designations (n, %) | 120 (71.0%) | 121 (71.6%) | 119 (70.4%) | 95 (56.2%) | 86 (50.9%) | 95 (56.2%) | 81 (47.9%) | |

| Discordant tract designations (n, %) | 49 (29.0%) | 48 (28.4%) | 50 (29.6%) | 74 (43.8%) | 83 (49.1%) | 74 (43.8%) | 88 (52.1%) | |

All the estimates in the table are based on Census 2010 geographies.

DISCUSSION

This study replicated two spatial measures of community food access relevant to current US food access policy, using a single, verified dataset of the food environment and a standardized GIS protocol in a contiguous study area. This approach allowed us to explore differences in the methods and outcomes of the two measures un-confounded by inconsistencies in the underlying GIS methodologies or utilized data.

Despite the focus on food access conveyed by the name of the USDA ERS food desert measure,3, 4 this measures was actually designed to identify low income tracts that have low access, as mandated by the 2008 Farm Bill.11 Thus, the emphasis was on socio-economically disadvantaged populations.3, 17 In our study area of 169 tracts, 101 were considered low income and of those only 38 low food access, i.e. met the criteria for food deserts. In contrast, the CDC’s non-healthier retail tract measure was first presented as an environmental indicator in the context of a national report on state-level fruit and vegetable consumption.7, 9 No distinction by income levels was made, nor were potential access differences due to the generally larger areas comprised by rural census tracts than urban tracts integrated. Thus, the CDC’s approach was clearly conceived to be more population-wide than the USDA ERS approach. Given these conceptual differences, it is not suprising that our study found that the USDA ERS food desert measure identified a somewhat smaller number of census tracts as having poor food access than the CDC measure.

However, contrary to our expectation, both measures showed a relatively high degree of consistency with about 71% of census tracts receiving an identical designation as being an area of poor food access (or not) by the two community food access measures. Our sensitivity analyses revealed that the combination of the low income and low access criteria used by the USDA ERS actually substantially improved consistency with the CDC’s measure, while the slight differences in the types of food outlets considered eligible by either measure did not materially affect the levels of consistency. These findings suggest that even though the CDC’s non-healthier retail tract measure ostensibly considers only the absence or presence of a healthier food retail outlet within a census tract, in an empirical application to our data, this criteria is likely strongly associated with area-level socio-economic characteristics. Given the exploratory and quite limited nature of our sensitivity analyses, replications of these types of evaluations in other data sets are much needed.

There are a number of noteworthy GIS-related methodological differences and limitations of the two measures of community food access. Distances were important components of the computational algorithm for the USDA ERS food desert which utilized Euclidian (straight-line) distances. Had the USDA ERS algorithm been applied using street network distances, the number of census tracts considered food deserts would have been markedly higher, i.e. 69 (40.8%) instead of 38 (22.8%). Furthermore, the consideration of an exterior buffer was of differing importance to the two measures. Inclusion of a 10-mile exterior buffer zone did not change any of the USDA food desert designations, but one additional census tract was designated a non-healthier retail tract according to the CDC measure. Both measures were susceptible to influences of edge effects as both were based on the aggregation of stores to census tracts.18 Our replication of the two measures used census tract boundaries corresponding to the year 2010 and corresponded to the methodology used by the 2013 USDA ERS Food Access Research Atlas5, 8, 14 and the 2013 CDC report.7 Both measures relied on census tract geographies, which, like any arbitrary areal unit, are subject to boundary and modifiable areal unit problems.19, 20 Furthermore, replication of the USDA ERS measure required more advanced GIS methods, while the CDC’s measure was clearly easier to replicate. The use of 0.5 km ×0.5 km grid cells for the computation of access characteristics was clearly a highly sophisticated approach. Last but not least, a conceptual limitation of the USDA ERS measure is that it included only supermarkets and large grocery stores as outlets for healthy food but not farmers’ markets or other local sources of healthy foods. In contrast, the CDC’s measure includes fruit and vegetable markets (i.e. specialty stores) which is in line with the interest in promoting fruit and vegetable consumption (including fresh produce), consistent with other metrics of the CDC’s 2013 state indicator report such as the number of farmers markets and the number of food hubs.7

While research on access to healthy food, the retail food environment, and food choices increasingly suggests that lack of access to supermarkets contributes to poor diet quality, the literature is not entirely consistent on this issue.21–31 Areas characterized by poor spatial access to healthier food retailers were labeled “food deserts” long before the term was introduced into the 2008 US Farm Bill.10, 32–34 There have been several in-depth discussions of whether food deserts actually exist, how they may be defined, and what data sources are needed for their identification locally or nationally.35–37 However, to the best of our knowledge a systematic, data-based comparison of the USDA ERS food desert measure with the CDC’s measure of non-healthier retail tracts has not been published.

Over the past years, the US government has invested millions of dollars to improve retail food environments – and thereby spatial food access - particularly in underserved communities through initiatives such as Communities Putting Prevention to Work and the Healthy Food Financing Initiative.1, 6, 7, 38 Spatial food access problems could also be addressed in the context of existing food assistance policies if, for instance, benefit levels were to consider the higher transportation costs for residents of food deserts.36 In parallel, public health practitioners and food policy councils are increasingly conducting local assessments of food retail environments in their neighborhoods, communities or states. Tailored to practitioners, the CDC recently released an action guide and toolkit along with the Children’s Food Environment State Indicator Report.6, 39 In this context, our study suggests that there inherent limitations in both measures due to the reliance on aggregated, Census-tract based definitions and the use of a limited number of specific store types as proxies for healthy food retail choices.

A number of limitations and strengths are worth considering. We recognize that our boundary buffer area was not verified, which may have resulted in a small amount of error given known inaccuracies in secondary data sources.12, 13 However, given that we used two data sources to create this buffer, including the data source known to be of the highest quality in South Carolina, we suspect that the amount of error should have been small. Secondly, one needs to recognize that our field census data did not include farmers markets or road side stands. Thus, it is possible that we somewhat underestimated potential differences between tract designations due to food outlet type differences in the USDA ERS versus the CDC criteria, as we found only one of 169 census tracts changed designations. Furthermore, we do not claim that our findings are generalizable to the entire US, however, they are very consistent with data published by the two agencies. For instance, the USDA ERS Food Access Research Atlas shows that 21% of census tracts in our study area were considered food deserts in 2010.8

CONCLUSIONS

Growing interest in locally grown foods, the farmer’s market movement, and heightened awareness of food access issues by community members and food policy councils has increased interest in being able to identify and describe environments in terms of their community food access characteristics. From a practical perspective, the USDA ERS food desert measure is likely the easiest to obtain given the availability of the USDA Food Access Research Atlas and the Food Desert locator websites, both of which allow the user to characterize specific census tracts or download entire data sets.4, 5 However, it is important to recognize that this measure specifically targets low income areas which have low access to healthier food retailers. Thus, the food desert measure is likely to identify a somewhat smaller number of census tracts than the CDC’s approach. Conceptually, the CDC’s healthier food retailer measure may be the more intuitive measure, in the sense that it simply focuses on the availability of a supermarket or large grocery store within the boundaries of a census tracts (and ½ mile thereof). However, to the best of our knowledge, this measure is not readily available to a user at the census tract level, but only in an aggregate form as part of the State Indicator Report on Fruit and Vegetables.7

The results of the present study offer a direct and systematic comparison between two spatial measures of community food access, the USDA ERS food deserts and the CDC’s healthier retail tracts, and highlight both similarities and differences in the conceptual frameworks and methodologies between these measures. Our comparison revealed that they designated about 71% of census tracts in an identical manner, with the remaining 29% of tracts designated discordantly. Given the attention that spatial food access has received by the public and media,40, 41 there seems to be a need for greater harmonization of these measures of community food access, especially from the consumer’s perspective. Our findings furthermore suggest that a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of various criteria embedded in the food access measures, ideally using empiric data analyses paired with simulation studies, may be highly informative for potential harmonization efforts and refinements of these measures of community food access.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was received through a grant from the RIDGE Center for Targeted Studies at the Southern Rural Development Center at Mississippi State University. The food environment data were funded by NIH 1R21CA132133. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the RIDGE Center for Targeted Studies or the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

None.

Authors’ Contributions

ADL developed the idea for this manuscript, acquired and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. JDH participated in acquisition of data, geocoded the data and conducted GIS-based data management. XM conducted statistical analyses. BAB provided statistical expertise. SEB provided geographic expertise. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Health Food Financing Initiative. U S Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed on April 27, 2011]. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2010pres/02/20100219a.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett CB. Food security and food assistance programs. Handbook of agricultural economics. 2002;2:2103–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ver Ploeg M, Breneman V, Farrigan T, Hamrick K, Hopkins D, Kaufman P. Access to affordable and nutritious food - measuring and understanding food deserts and their consequences: Report to Congress. 2009. Report No.: AP-036. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Agriculture ERS. USDA Food Desert Locator documentation. U S Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; [Accessed on March 22, 2013]. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/dataFiles/Food_Access_Research_Atlas/Download_the_Data/Archived_Version/archived_documentation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Agriculture ERS. USDA Food Access Research Atlas. U S Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; [Accessed on March 22, 2013]. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Children’s Food Environment State Indicator Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed on November 5, 2012]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/childrensfoodenvironment.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Accessed on September 2, 2013]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/downloads/State-Indicator-Report-Fruits-Vegetables-2013.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Agriculture ERS. USDA Food Access Research Atlas data download and current and archived version of documentation. U S Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; [Accessed on March 22, 2013]. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/download-the-data.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 9.State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Accessed on October 25, 2010]. Available at: http://www.fruitsandveggiesmatter.gov/downloads/StateIndicatorReport2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. [Accessed on April 18, 2013];Farm Bill. Available at: http://www.usda.gov/documents/Bill_6124.pdf.

- 11.Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Title VI, Sec. 7527. Study and report on food deserts. [Accessed on April 18, 2013];Farm Bill. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-110hr6124eh/pdf/BILLS-110hr6124eh.pdf.

- 12.Liese AD, Colabianchi N, Lamichhane A, et al. Validation of Three Food Outlet Databases: Completeness and Geospatial Accuracy in Rural and Urban Food Environments. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;172(11):1324–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liese AD, Barnes TL, Lamichhane AP, Hibbert JD, Colabianchi N, Lawson AB. Characterizing the food retail environment: impact of count, type and geospatial error in two secondary data sources. Journal Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2013;45(5):435–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ver Ploeg M, Breneman V, Dutko P, et al. Access to affordable and nutritious food: updated estimates of distance to supermarkets using 2010 data. 2012. Nov, Report No.: ERR-143. [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Agriculture ERS. USDA Food Desert Locator. U S Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; [Accessed on July 22, 2011]. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data/fooddesert. [Google Scholar]

- 16.2010 Census urban and rural classification and urban area criteria. U S Census Bureau, Geography Division; 2010. [Accessed on December 3, 2012]. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/www/ua/2010urbanruralclass.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutko P, Ver Ploeg M, Farrigan T. Economic Research Report No (ERR-140) 2012. Characteristics and influential factors of food deserts; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Meter EM, Lawson AB, Colabianchi N, et al. An evaluation of edge effects in nutritional accessibility and availability measures: a simulation study. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Openshaw S. The modifiable areal unit problem. 38. Geo books Norwich; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewko J, Smoyer-Tomic KE, Hodgson MJ. Measuring neighbourhood spatial accessibility to urban amenities: does aggregation error matter? Environment and Planning A. 2002;34(7):1185–206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morland K, Wing S, Diez-Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002 Jan;22(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR., Jr Associations of the local food environment with diet quality--a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Apr 15;167(8):917–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmonds J, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Cullen KW, Myres D. Ecological and socioeconomic correlates of fruit, juice, and vegetable consumption among African-American boys. Prev Med. 2001 Jun;32(6):476–81. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franco M, Diez-Roux AV, Nettleton JA, et al. Availability of healthy foods and dietary patterns: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Mar;89(3):897–904. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Kaufman JS, Jones SJ. Proximity of supermarkets is positively associated with diet quality index for pregnancy. Prev Med. 2004 Dec;39(5):869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005 May;19(5):330–3. ii. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodor JN, Rose D, Farley TA, Swalm C, Scott SK. Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutr. 2008 Apr;11(4):413–20. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An R, Sturm R. School and residential neighborhood food environment and diet among California youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Feb;42(2):129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee H. The role of local food availability in explaining obesity risk among young school-aged children. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Apr;74(8):1193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung CW, Laraia BA, Kelly M, et al. The influence of neighborhood food stores on change in young girls’ body mass index. Am J Prev Med. 2011 Jul;41(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson N, Story M. A review of environmental influences on food choices. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:56–73. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beaulac J, Kristjansson E, Cummins S. A systematic review of food deserts, 1966–2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009 Jul;6(3):A105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health Place. 2010 Sep;16(5):876–84. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bitler M, Haider SJ. An economic view of food deserts in the United States. National Poverty Center/United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Conference; 2009. Jan 23, [Accessed April 18, 2013]. Available at: http://www.npc.umich.edu/news/events/food-access/final_bitler_haider.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose D, Bodor JN, Swalm CM, Rice JC, Farley TA, Hutchinson PL. Deserts in New Orleans? Illustrations of urban food access and implications for policy. National Poverty Center/United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Conference; 2009. Jan 23, [Accessed April 18, 2013]. Available at: http://www.npc.umich.edu/news/events/food-access/rose_et_al.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowaleski-Jones L, Fan JX, Yamada I, Zick CD, Smith KR. Alternative Measures of Food Deserts: Fruitful Options or Empty Cupboards? National Poverty Center/United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Conference; 2009. Jan 23, [Accessed April 18, 2013]. Available at: http://www.npc.umich.edu/news/events/food-access/kowaleski-jones_et_al.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Communities Putting Prevention to Work. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; [Accessed on May 24, 2011]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/CommunitiesPuttingPreventiontoWork. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Healthier Food Retail. Beginning the Assessment Process in Your State or Community. Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity (DNPAO) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed on May 21, 2012]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/hfrassessment.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kase A. Failure of Germantown Grocery Raises Questions of Pay-to-Play. [Accessed on August 20, 2011];Philadelphia Weekly. Available at: http://www.philadelphiaweekly.com/news-and-opinion/Failure-of-Germantown-Grocery-Raises-Questions-of-Pay-to-Play.html.

- 41.Mui Ylan Q. First lady, grocers vow to build stores in ‘food deserts’. [Accessed on July 20, 2011];The Washington Post (Business) Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/first-lady-grocers-vow-to-build-stores-in-food-deserts/2011/07/20/gIQA9LHRQI_story.html.