Abstract

Background

To evaluate the prevalence of BAP1 germline mutations in a series of young patients with uveal melanoma (UM), diagnosed before age 30.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out on 14 young uveal melanoma patients (average age 21.4 years, range 3 months to 29 years). Germline DNA was extracted from peripheral blood. BAP1 sequencing was carried out using direct sequencing of all exons and adjacent intronic sequences. We also tested for germline mutations in additional melanoma-associated candidate genes CDKN2A and CDK4 (exon 4).

Results

We identified one patient with a pathogenic mutation (c. 1717delC, p.L573fs*3) in BAP1. This patient was diagnosed with UM at age 18 years and had a family history of a father with UM and a paternal grandfather with cancer of unknown origin. One additional patient had an intronic variant of uncertain significance (c.123-48T>G) in BAP1 while the remaining 12 patients had no alteration. None of the patients had CDKN2A or CDK4 (Exon 4) mutations. Family history was positive for a number of additional malignancies in this series, in particular for cutaneous melanoma, prostate, breast and colon cancers. There were no families with a history of mesothelioma or renal cell carcinoma.

Conclusions

This study suggests that a small subset of patients with early onset UM has germline mutation in BAP1. While young patients with UM should be screened for germline BAP1 mutations, our results suggest that there is a need to identify other candidate genes which are responsible for UM in young patients.

Keywords: BAP1, familial cancer, uveal melanoma

INTRODUCTION

The BAP1 (BRCA1-associated protein-1) Tumor Predisposition Syndrome (TPDS) is a recently recognized hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome (OMIM #614327).1–4 Four main cancers: uveal melanoma (UM), cutaneous melanoma, mesothelioma, and renal cell carcinoma are clearly associated with this syndrome, and others have been suggested.1–4 UM is the earliest reported cancer in this syndrome, with one diagnosis at age 16.5 This is much earlier than the mean age of onset for UM of age 60.6

While clinical case series have shown that UM in younger patients are often smaller in size and may have predisposing factors such as ocular melanocytosis, little is known about predisposing genetic factors.7,8 Better elucidation of the underlying genetic mechanisms is therefore extremely important as it could help to provide better prognostic data, identify potential therapeutic targets, assess risk for additional malignancies, and assess risk of transmission to offspring. Given that germline BAP1 mutations are associated with an early onset of UM, the purpose of this study was to analyze a series of young patients from two ocular oncology centers with a diagnosis of UM under age 30 for germline BAP1 mutations. We hypothesized that: (1) there would be an increased prevalence of BAP1 germline mutations in young patients with UM, and (2) there would be an increased incidence of a positive family history for hereditary cancer predisposition in these young patients with UM.9

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Family History

Analysis

Approval for this project was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University (2006C0045) and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation (CCF 2365). This project was HIPAA compliant and in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patients if older than age 18 years or from their parents if younger than 18. All patients with a diagnosis of UM younger than 30 years were eligible for the study. All patients were assigned an alpha-numeric code. Family cancer history and clinical data were obtained for each study participant. Patients were accrued over a period of 8 years. Clinical and ophthalmological data were obtained from patients’ charts. For several patients tumor characteristics were not available, Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of family cancer history in patients with early onset uveal melanoma included in the study

| Patient ID | Reference of previous report | Age* | Gender | Other malignancy in patient | Malignancy in relatives | Tumor location | Tumor size (base × height, mm) | Treatment | AJCC T Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUM1474 | – | 29 years | F | None | CM and Prostate(F), Colon (PGM), Breast (M), CM (MU), Prostate (MGF) | Choroid | NA | FNAB, brachytherapy | N/A |

| FUM039 | 4 | 28 years | M | None | CM (B) | Choroid | 6.5 × ? | Brachytherapy | N/A |

| FUM101 | 12 | 28 years | F | None | None | Choroid | 14 × 12 | Enucleation | T3 |

| FUM012 | 4 | 27 years | M | None | Breast (MU), CASU (MU), Lung (MGM, Eye NOS (MC) | Ciliary body | 10 × 9 | Enucleation | T2 |

| FUM078 | 12 | 27 years | M | None | CM (PGF), Brain (PC) | Choroid | 18 × 4 | Enucleation | T4 |

| FUM014 | 4 | 27 years | F | None | Cervix (S), Lymphoma (MGM) | Choroid | 3 × 4 | No treatment | T1 |

| FUM063 | 12 | 25, 30 years (bilateral) | F | Breast | Acoustic neuroma and Astrocytoma (S) Throat (F), Throat (PU), Head & Neck (PA), Bladder (MA), Head & neck (MU) | NA | NA | NA | N/A |

| FUM069 | 12 | 23 years | F | None | Breast (PGGM), Prostate (PGGF) | Ciliary body | 3.8 × 3.3 | Iridocyclectomy | T1 |

| FUM013 | 4 | 19 years | F | None | Lymphoma & Breast (PA), Breast (PA), Colon (MU), Sinus (MGF) | Choroid | 12 × 3 | Brachytherapy | T1 |

| FUM152 | – | 18 years | F | None | UM (F), Cancer NOS (PGF) | Choroid | 6.5 × 3.5 | Brachytherapy | T1 |

| CEI6605 | – | 17 years | F | None | CM (MGM), Prostate (MGGM), Prostate (PGGF) | Iris | 9 × ? | FNAB, brachytherapy | N/A |

| CEI6627 | – | 17 years | M | None | Skin NOS (PA), Pancreas (PC), Bone and Prostate (PGF) | Iris | NA | Iridectomy | N/A |

| FUM066 | 12 | 15 years | F | None | Testicular (F) | Choroid | 7 × 1.7 | Brachytherapy | T1 |

| CEI6601 | – | 3 months | F | None | None | Ciliochoroidal with extrascleral involvement | 20 × 4 | Enucleation | T4 |

Family history symbols: F, father; M, mother; P, paternal side of the family; M, maternal side of the family; S, sister; B, brother; GM, grandmother; GF, grandfather; A, paternal aunt; U, uncle; C, cousin; GGF, great grandfather; GGM, great grandmother; CaSU, cancer site unknown; CM, cutaneous melanoma; N/A, not available; NOS, not otherwise specified; WT, wild type

age at diagnosis

Germline DNA Sequencing

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from each participant. Peripheral blood leukocytes were isolated by centrifugation and extraction of the buffy coat layer and germline DNA was extracted using a salting out procedure.10 PCR was used to perform direct sequencing of all exons and adjacent intronic sequences for the BAP1 gene as previously described.4 Mutational screening for the melanoma-associated genes CDKN2A and CDK4 (Exon 4) were also carried out for patients as described if not previously done.11 Seven of these patients were presented in previous studies, Table 1.4,12 For two patients (FUM147 and FUM063) with a strong personal and/or family history of breast cancer, a mutation in BRCA1/BRCA2 was ruled-out by testing performed in a clinical setting independent of this study.

RESULTS

BAP1, CDKN2A and CDK4 Gene Mutation Data

One patient (FUM152, III-2) was found to have a germline single base pair deletion in the coding region of the BAP1 gene (c. 1717delC, p.L573fs*3) causing a frame shift and subsequent truncation of the BAP1 protein, see Figure 1. An additional patient, FUM147, was found to have an intronic variant of uncertain significance (c. 123-48T>G). Splice site prediction, utilizing both NetGene 2 version 2.4216 and NNSPLICE version 0.9 software,17 indicated that this variant is not a potential splice-site, suggesting that it is likely not pathogenic. No pathogenic germ-line mutations in BAP1, CDKN2A or exon 4 of CDK4 were detected in any of the other 12 patients tested.

FIGURE 1.

Family history and sequencing results of the patient with BAP1 mutation. (A) Pedigree of the patient (FUM152, III-2) with germline BAP1 mutation. The patient had a personal history of UM with family history of UM of her father and a cancer of unknown origin in her paternal grandfather. (B) Sequencing identified a germline frameshift mutation c. 1717delC caused by deletion of a single base, p.L573fs*3 (confirmed by forward and reverse sequencing).

Clinical Data and Family Cancer History

The majority of UM tumors in this series were located in the choroid (n = 8), two were located in the ciliary body, two were located in the iris, and one was found to be ciliochoroidal with extrascleral involvement, Table 1. Tumor location data were not available for one patient. Surprisingly the patient with extrascleral extension was the youngest patient in the series (age 3 months) with pathologic confirmation of UM diagnosis. Importantly, the patient in the series with a germline BAP1 mutation was treated with brachy-therapy for AJCC T1a choroidal melanoma at age 18 years and developed biopsy-proven metastases to breast and bone at age 27.

Tumor size at diagnosis is reported to be smaller in juvenile patients with UM than older patients.13 In this study, tumor size data were not available for all patients. However, from the data available, tumor size was large in several patients. Tumor dimensions ranged from a basal diameter of 3–20 mm (mean = 9.98) and a height of 1.7–12 mm (mean = 4.94, see Table 1. The tumors were treated with brachytherapy, enucleation, iridectomy, or iridocyclectomy, Table 1.

The cancer family history for the patient with the germline BAP1 mutation was significant for UM in the patient's father at age 45 and his subsequent death from metastatic disease at age 49 (FUM152, Figure 1). A paternal grandfather had a cancer of unknown origin. One family, FUM012, also reported one third degree relative with a history of “eye cancer” at age 10 years but we could not confirm the pathology of the tumor. There were three families with a positive history of cutaneous melanoma, which is a major cancer type associated with the BAP1 TPDS, see Table 1. Family history for the other BAP1 TPDS cancers (mesothelioma and renal cell carcinoma) was negative in all 14 patients.

For most patients, there was little data in the chart review regarding characteristic skin lesions of the BAP1 TPDS or oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota). The proband of FUM152, with pathogenic BAP1 mutation, had no report of any abnormal skin lesions or sign of melanocytosis/nevus of Ota on clinical examination records. However, the 3-month-old pro-band (CEI6601) had a pathology-confirmed periocular blue nevus.

Family history was positive for other cancers in many first, second and third degree relatives, Table 1. The most common malignancies identified in relatives were prostate cancer (n = 6), breast cancer (n = 5), cutaneous melanoma (n = 5), colon cancer (n = 2), and lymphoma (n = 2).

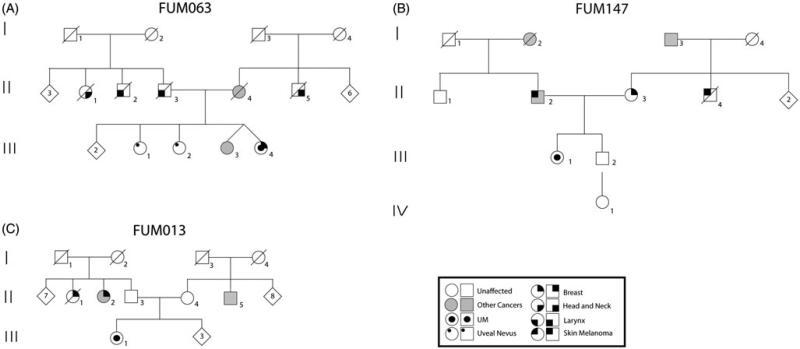

Three patients reported significant cancer histories on both the maternal and paternal sides of their family FUM147, FUM063 and FUM013, see Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Pedigrees of patients with a strong family history of different cancers. (A) The proband (III-5) of FUM063 presented with bilateral uveal melanoma (25, 30 years) and breast cancer (35 years). The family history was also positive for two siblings (III-2 and III-3) with large uveal nevi. The proband's twin sister (III-4) had an acoustic neuroma and astrocytoma. Several other cancers were reported on both sides of the family. (B). The proband (III-1) of FUM147 presented with uveal melanoma at age 29 years and with a family history of breast cancer in the mother (34 years), cutaneous melanoma in the maternal uncle (23 years), and prostate cancer in the maternal grandfather (76 years). The proband's father also had both cutaneous melanoma (in his 40s) and prostate cancer (60 years). The paternal grandmother had colon cancer (70 years). (C) The proband (III-1) of FUM013 presented with uveal melanoma and had a family history of two paternal aunts with breast cancer, while one of them additionally had lymphoma. Colon cancer was present in a maternal uncle.

DISCUSSION

With the discovery of the BAP1 TPDS it became important to identify which UM patient should be tested for this syndrome.1–4 Early age of cancer onset is an important feature of high-risk for hereditary predisposition to cancer.14 As such, it seems logical to test these patients for germline mutation in BAP1. However, the prevalence of germline mutation in patients with early onset UM is still unknown. The answer to this question is not just an academic exercise but has important implications for counseling of patients and family members of patients with early onset UM. In this study, we identified a pathogenic germline mutation in BAP1 in 1/14 (7.1%) of patients with early onset UM. These findings support the screening of young patients for germline BAP1 mutations, but also suggest the existence of other candidate genes predisposing to cancer in these patients. There is a need to counsel, educate, and encourage these patients and their families to enroll in research studies for the discovery of other candidate genes.

Many of these young individuals in this series had a family history which was positive for a number of diverse malignancies, as shown in Table 1. Therefore, it is important to consider that there may be germline mutations in genes other than BAP1, especially in patients with a strong family history of multiple malignancies. Moreover, several of the youngest patients in the study had very limited family histories of malignancy which may simply be due to the fact that even though they harbor germline mutations, their family members may not have yet developed malignancies but could still be at high risk for developing them in the future, Table 1. Conversely, a lack of extensive family history could also represent a de novo germline mutation in these patients. That could place their future offspring at greater risk for developing malignancy at a young age. Thus, further work is needed to follow these patients and their families over time in order to determine whether additional family members develop malignancies. Interestingly, several patients had a family history of cancer on both sides of the family, suggesting the potential contribution of more than one genetic event contributing to the early development of cancer in these patients. For example, one possibility is the inheritance of a driver mutation for cancer from one side of the family with the inheritance of a modifier gene from the other side of the family. This synergistic effect could predispose some patients to early onset of cancer.

Precisely which additional genes are mutated in these patients remains an important question for further study. It has been suggested that UM patients have a genetic predisposition to develop atypical nevi and CM,15 which has led to interest in melanoma predisposition genes such as CDKN2A, CDK4, and P14ARF. Previous work looking for germline mutations in these genes as well as GNAQ, GNA11 and BRCA2, in patients with uveal melanoma revealed rare cases of mutations in BRCA2 and CDKN2A, while the other genes showed negative results.11,16–22 Therefore, more candidate genes, in addition to BAP1, need to be studied in order to identify the gene or genes mutated in these patients. Advances in sequencing technology now allow for screening the whole genome or exome for candidate genes and future studies could utilize these techniques to identify novel hereditary predisposition candidates.

While previous work has shown that tumors in young patients with uveal melanoma are often smaller in size, our study found a range of both large and small tumors, Table 1.13 Surprisingly, the largest tumor was found in a 3-month-old and was found to have extra-scleral extension, Table 1.

While this individual was not found to have a germline BAP1 mutation, the very early age of onset suggests that this child could harbor an underlying germline mutation in a gene other than BAP1. It is possible that large tumor size in a young patient could represent another high risk feature for TPDS and further work will address whether this patient harbors a germline mutation in a gene other than BAP1.

In conclusion, we have identified a BAP1 germline gene mutation in a young patient with UM. This finding suggests that BAP1 screening should be considered in young patients with UM given its prognostic significance for both the individual and their families. This is particularly important for those with either a personal and/or family history suggestive of the BAP1 TPDS, as well as those patients with small families and a very young age at presentation. This study highlights the importance of finding additional candidates besides BAP1 in these young patients with UM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08EY022672. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these institutions. Additional funds were provided by the Patti Blow research fund, The American Cancer Society IRG-67-003-47, The Melanoma Know More Foundation, The Ocular Melanoma Foundation, and The Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation. These funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Popova T, Hebert L, Jacquemin V, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to renal cell carcinomas. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:974–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Murali R, et al. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/ng.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1022–1025. doi: 10.1038/ng.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Rahman MH, Pilarski R, Cebulla CM, et al. Germline BAP1 mutation predisposes to uveal melanoma, lung adenocarcinoma, meningioma, and other cancers. J Med Genet. 2011;48:856–859. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoiom V, Edsgard D, Helgadottir H, et al. Hereditary uveal melanoma: a report of a germline mutation in BAP1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:378–384. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh AD, Topham A. Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973–1997. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:956–961. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh AD, Shields CL, Shields JA, Sato T. Uveal melanoma in young patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:918–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh AD, Shields CL, De Potter P, et al. Familial uveal melanoma. Clinical observations on 56 patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:392–399. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130388005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Rahman MH, Pilarski R, Ezzat S, et al. Cancer family history characterization in an unselected cohort of 121 patients with uveal melanoma. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:431–438. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SA, Dykes DD. Polesky HFrn. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel-Rahman MH, Pilarski R, Massengill JB, et al. Melanoma candidate genes CDKN2A/p16/INK4A, p14ARF, and CDK4 sequencing in patients with uveal melanoma with relative high-risk for hereditary cancer predisposition. Melanoma Res. 2011;21:175–179. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328343eca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilarski R, Cebulla CM, Massengill JB, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype of hereditary BAP1 cancer predisposition syndrome, reporting three new cases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:177–182. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Arepalli S, et al. Uveal melanoma in children and teenagers. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2013;27:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampel H, Sweet K, Westman JA, et al. Referral for cancer genetics consultation: a review and compilation of risk assessment criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41:81–91. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.010918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hees CL, de Boer A, Jager MJ, et al. Are atypical nevi a risk factor for uveal melanoma? A case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:202–205. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12392754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz C, Teule A, Caminal JM, et al. Uveal melanoma and BRCA1/BRCA2 genes: a relationship that needs further investigation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e827–829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buecher B, Gauthier-Villars M, Desjardins L, et al. Contribution of CDKN2A/P16 (INK4A), P14 (ARF), CDK4 and BRCA1/2 germline mutations in individuals with suspected genetic predisposition to uveal melanoma. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:663–667. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdel-Rahman MH, Pilarski R, Massengill JB, et al. Lack of GNAQ germline mutations in uveal melanoma patients with high risk for hereditary cancer predisposition. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:319–321. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hearle N, Damato BE, Humphreys J, et al. Contribution of germline mutations in BRCA2, P16(INK4A), P14(ARF) and P15 to uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:458–462. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott RJ, Vajdic CM, Armstrong BK, et al. BRCA2 mutations in a population-based series of patients with ocular melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:188–191. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iscovich J, Abdulrazik M, Cour C, et al. Prevalence of the BRCA2 6174 del T mutation in Israeli uveal melanoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:42–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinilnikova OM, Egan KM, Quinn JL, et al. Germline BRCA2 sequence variants in patients with ocular melanoma. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:325–328. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990730)82:3<325::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]