Abstract

The use of animals in various assistive, therapeutic, and emotional support roles has contributed to the uncoordinated expansion of labels used to distinguish these animals. To address the inconsistent vocabulary and confusion, this article proposes a concise taxonomy for classifying assistance animals. Several factors were identified to differentiate categories, including (1) whether the animal performs work or tasks related to an individual’s disability; (2) the typical level of skill required by the animal performing the work or task; (3) whether the animal is used by public service, military, or healthcare professionals; (4) whether training certifications or standards are available; and (5) the existence of legal public access protections for the animal and handler. Acknowledging that some category labels have already been widely accepted or codified, six functional categories were identified: (1) service animal; (2) public service animal; (3) therapy animal; (4) visitation animal; (5) sporting, recreational, or agricultural animal; and (6) support animal. This taxonomy provides a clear vocabulary for use by consumers, professionals working in the field, researchers, policy makers, and regulatory agencies.

Keywords: assistance animal, assistance dog, nomenclature, public access rights, service animal, service dog, support animal, taxonomy, therapy animal, vocabulary

INTRODUCTION

Service dog, assistance dog, guide dog, seeing-eye dog, hearing dog, mobility assistance dog, seizure-alert dog, police dog, search-and-rescue dog, drug-detection dog, bomb-detection dog, working dog, therapy dog, visitation dog, emotional support dog, sport dog, show dog, hunting dog, companion dog, and pet are examples of various labels given to dogs in our society. Dogs have been used by humans throughout history for companionship, hunting and herding, sport and recreation, security and protection, military support, emotional support, and assistance with physical and psychiatric disabilities [1–3]. There has been a recent increase in the use of dogs in many different therapeutic, assistive, and emotional support roles [4] and a subsequent uncoordinated expansion in labels used to distinguish these dogs. The arising inconsistency in the taxonomy has created confusion among consumers, professionals working in the field, researchers, policy makers, and regulatory agencies [5].

Others have recognized this confusion and attempted to make distinctions by defining common labels. One assistance dog advocacy organization, Assistance Dogs International (ADI), has promoted definitions of assistance dog and service dog that are widely cited and accepted by many service dog trainers, but the definitions are not universally used among laypeople or healthcare personnel nor are they aligned with definitions that appear in Federal or state laws. Others have attempted to distinguish therapy dogs (used for hospital and nursing home visitations) from dogs used in recreational or other therapeutic activities [6–8]. However, no standard or universally accepted taxonomy has emerged. More recently, Mills and Yeager classified at least 12 different types of animals used in healthcare and military settings [9]. Although comprehensive and inclusive of many different types of assistance animals, this classification scheme does not adequately capture the essential characteristics that differentiate and define the types of assistance animals.

The objectives of this article are to identify possible sources of inconsistency or confusion that arise from the existing labels given to assistance animals and suggest a revised taxonomy to better classify and differentiate the multiple assistive, work, and recreational functions that animals, and especially dogs, offer humans.

VOCABULARY OF ASSISTANCE ANIMALS IN SOCIETY

It must be acknowledged that not every label or term currently used causes confusion. Many labels are accepted and widely used without much risk of being misunderstood. Labels for animals that provide assistance in sports and various work-related activities are often sufficiently descriptive. For example, dogs that assist with hunting activities are commonly referred to as hunting dogs; dogs used to assist with herding other animals are called herding dogs; dogs that participate in competitive activities such as conformation and obedience are called show dogs; and dogs that assist in seeking, locating, and rescuing activities are called search-and-rescue dogs. Although slight variations can and do exist among these labels, there is an obvious correspondence between the labels and the assistive function they specify.

Similar correspondences exist with labels given to animals that provide assistance to individuals with physical and psychological impairments. The first documented reports of assistance dogs described dogs used for people with vision impairment [5]. These dogs are typically referred to as guide dogs, leader dogs, or seeing-eye dogs. As methods were developed and dogs were trained to assist individuals with hearing impairment, the labels hearing dogs, signal dogs, hearing-ear dogs, and alert dogs emerged [10]. More recently, the label psychiatric service dog has been used for dogs trained to help individuals with psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury, and autism. Similarly, the label seizure-alert dog has been used for dogs that have been purported to detect the onset of seizures. Because these labels unambiguously identify the disability for which the dog provides assistance, the labels have a certain amount of face value that minimizes confusion or inconsistency. On the other hand, a limitation of some specific labels is that they do not convey the relevant functional group or category to which the dogs belong. For example, an emotional support dog may indeed provide some type of comfort or assistance to an individual with a psychological disorder, but it may or may not meet the legal definition of a service dog.

Confusion seems to arise more often when the labels do not clearly specify the assistive function of the animal. In these cases, the labels may be either too generic (i.e., can refer to more than one kind of assistive function) or misleading (i.e., specifies an unrelated function). For example, the label guide dog is most typically used to refer to a dog that assists an individual with vision impairment, but it has also been used to describe a dog that assists an individual with Alzheimer disease [11] or a dog that is specially trained to assist an individual with hearing impairment [12]. Dogs used to assist individuals with mobility impairments are often labeled generically as service dogs [13], assistance dogs [14], and support dogs [15], but in these cases, the labels do not provide sufficient information to identify the assistive function. Service dogs have been described as a mobility assistant only [16] or any type of dog that provides assistance for a disability other than for vision or hearing impairments [17]. Because these category labels do not specify the dog’s specific function, they can refer to any dog that provides service, support, or assistance to people, such as police dogs, hunting dogs, herding dogs, military dogs, and emotional support dogs. As another example, the label therapy dog is used by some to identify a dog that visits individuals in a nursing home or hospital [8], but it has also been used to identify dogs used within the scope of a healthcare or allied healthcare treatment plan [7, 18].

Confusion also arises with the use of multiple labels for animals performing the same function. Dogs that visit individuals in nursing homes and hospitals have been called therapy dogs and visitation dogs, among other labels. Likewise, several different terms have become popular to describe the variety of assistances a dog can provide for individuals with psychiatric impairments (i.e., therapy dogs, pet adjuncts, emotional support dog). In a review of animal-assisted therapy, we found as many as 20 different definitions and 12 different terms, including animal-assisted therapy, animal-facilitated counseling, pet therapy, pet psychotherapy, pet-facilitated therapy, pet-facilitated psychotherapy, pet-mediated therapy, pet-oriented therapy, animal recreation, pet visitation, and others [19].

Labels may also be misleading. The use of the term therapy dog for dogs that visit nursing homes or hospitals to provide comfort and support is misleading because these types of animal visitation programs do not constitute therapy in a strict sense of the word. Therapy is defined as the “treatment of a disease or disorder” [20] or “treatment of a bodily, mental, or behavioral disorder” [21]. In distinguishing therapy from other events that have positive emotional effects, Beck and Katcher stated “It should not be concluded that any event that is enjoyed by the patients is a kind of therapy. . . . Ice cream, motion pictures, children, and electronic games all produce positive emotional responses in institutionalized elderly patients, yet none of those events would be called therapeutic in the scientific sense of the word” [6]. Others have argued that the individuals involved in what many describe as dog therapy could not ethically claim to be diagnosing or changing the course of a disease [7]. According to Kruger and Serpell, animal recreation and visitation programs should not be called therapy “just as we would not refer to a clown’s visit to a pediatric hospital as clown-assisted therapy” [7]. Organizations such as Pet Partners have also supported these notions by recommending explicitly that animal-assisted therapy and animal-assisted activities be clearly differentiated [8]. Nevertheless, the category of therapy dogs has evolved into an accepted term in both casual and professional vocabularies.

VOCABULARY OF ASSISTANCE ANIMALS IN FEDERAL AND STATE STATUTES

The vocabulary is also inconsistent across Federal and state statutes pertaining to the rights of individuals and their service animals to access public spaces. In 2011, an updated definition of service animal in the U.S. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 was enacted. Under the new definition, service animals are “dogs that are individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities, including a physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual, or other mental disability” [22]. As explained in the Federal Register notice that pertains to the ADA, doing work is intended to include activities that may not involve physical actions, whereas tasks are actions that can be physically exhibited [23]. Pulling a wheelchair is an example of a task, whereas calming an individual during a panic attack is an example of work. The ADA grants public access to dogs providing assistance to individuals with a variety of disabilities, and psychiatric service dogs are explicitly included. Dogs whose sole function is emotional support are explicitly excluded. Unlike the relatively clear and concise ADA definition, the definitions in U.S. regulations for public housing and transportation are vague [5] and in some cases conflict with the ADA. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) permits access to “animals that assist, support, or provide service to those with disabilities,” including both service and assistance animals, but these labels are not specifically defined or differentiated. HUD regulations state that an assistance animal is one that provides “emotional support to persons who have a disability-related need for such support” [24]. Likewise, according to the Air Carrier Access Act, a dog qualifies as a service dog if the individual needs the animal only for emotional support [25]. Similar variations exist in the definitions of service animals and public access protections in the laws of other nations [26–29].

State laws and regulations pertaining to service animals are no more consistent than those among the Federal agencies. Massachusetts is the only state that directly cites the ADA in its statute: “A person accompanied by and engaged in the raising or training of a service animal, including a hearing, guide or assistance dog, shall have the same rights, privileges and responsibilities as those afforded to an individual with a disability under the ADA” [30]. Many states have laws that are inconsistent with the current ADA. Some state laws and regulations are more restrictive. In 10 states (Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Oregon), service animals are only classified as dogs that assist individuals with physical disabilities; there are no provisions for dogs that assist individuals with psychiatric disorders. Some cities and states have enacted breed bans, which conflict with the ADA access protections for individuals with a service dog regardless of breed [31]. On the other hand, in some state laws, the specified functions of service dogs are more inclusive. Seven states (California, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, North Dakota, Utah, and West Virginia) include minimal protection as a qualifying task for service dogs even though the current ADA law states “the crime deterrent effects of an animal’s presence . . . do not constitute work or tasks” [22]. The specific labels used to identify service animals are inconsistent across states. For example, the label service dog is used in five states (Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, New Mexico, and Rhode Island), assistance dog or assistance animal is used in six states (Connecticut, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Oregon), and support dog or support animal is used in two states (Delaware and Iowa).

The lack of consistency, and in some cases, ambiguity in the laws and regulations gives rise to legal challenges. Common court cases involve complaints against public accommodations that refuse access to individuals and their service animals. For example, an appellate court found that a grocery store chain discriminated against an individual with PTSD by not permitting her to shop while accompanied by a service dog [32]. The main issue in this case was whether the individual had provided sufficient evidence of the dog’s training to distinguish it from an ordinary pet. Cases such as this are likely to increase as the role of assistance animal expands beyond assistance for obvious physical disabilities. These issues are not confined to the United States; similar cases have also occurred in Japan [33] and the United Kingdom [34]. The development and acceptance of a standard taxonomy is needed to provide a foundation for sound public policy and help guide public awareness. A clear vocabulary is necessary to advance the science and communicate findings across disciplines.

METHODS

Recommendations for Standardized Taxonomy

The Table shows a system that provides a novel structure for classifying categories of assistance animals. The table includes a recommended label for each functional category of animal, followed by various factors that differentiate them. Although others have identified other factors or considerations that further encompass or differentiate additional categories of assistance and companion animals (Mills and Yeager [9]), we purposively restricted the factors to a minimum set of considerations that sufficiently differentiate the mutually exclusive categories. These factors include (1) whether the animal performs work or tasks that are related to an individual’s disability; (2) the typical level of skill required by the animal in performing the work or task; (3) whether the animal is used by public service, military, or healthcare professionals; (4) whether training certifications or standards are available; and (5) the existence and scope of legal public access protection for the animal and handler. Incorporating distinctions promoted by others in the field where possible and acknowledging that some category labels have been widely accepted or codified, we identified six major functional categories of assistance animal: (1) service animal; (2) public or military service animal; (3) therapy animal; (4) visitation animal; (5) sporting, recreational, or agricultural animal; and (6) support animal. It is important to note that although the functional category of sporting, recreational, or agricultural animal is similar to the sporting and working breed groups of the American Kennel Club, the functional categories in our taxonomy do not imply any breed association. The categories herein are based solely on the function of the animal in society. Although the revised taxonomy may be adapted for primates, equines, felines, avians, bovines, and other species of animals used for assistance or companionship, much of the following discussion and examples will focus on dogs because they are the most commonly recognized assistance animal [9, 35]. Although pets can have therapeutic benefits for individuals with and without disabilities [36–37] and can often serve an important role in families [38], they are not included in this taxonomy.

Table.

Revised taxonomy for functional categories of assistance animals in society and major differentiating factors.

| Functional Category | Assistance Related to Disability |

Major Differentiating Factors |

Scope of Current Access Protections |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Level of Dog Skills |

Assists Public Service, Military, or Health Professional |

Certification or Standards Available |

|||

| Service Animal | Yes | Advanced | No | Yes | Broad* |

| Public Service or Military Animal | No | Advanced | Public service or military | Yes | Limited† |

| Therapy Animal | Varies | Varies | Health or allied health | Yes | None |

| Visitation Animal | No | Basic | No | Yes | None |

| Sporting, Recreational, or Agricultural Animal | No | Varies | No | Yes | None |

| Support Animal | Yes | Varies | No | No | Limited‡ |

Access to public locations is protected by Americans with Disabilities Act with some exceptions.

Access for public service or military animals is limited in most states to locations where handler and animal are on duty and otherwise legally present; in some states, broad access is protected regardless of duty status.

Support animals have protection under Federal regulations to reside in both public and private housing (Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988; Pet Ownership for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities, 2008). Resident is required to verify that animal is needed to assist with physical, psychiatric, or emotional need

Differentiating Factors

The first factor that helps to differentiate the function of animals is whether the animal provides assistance that is related to an individual’s disability. To be consistent with the ADA, assistance herein refers to work or tasks that are directly related to a physical or mental disability such as retrieving items, alerting to the presence of others, assisting with balance, alerting to sounds, disrupting flashbacks, or guiding to a specific location.

The second factor is whether the assistance or support provided by the animal requires either a basic or advanced skill level. Basic skills include tasks that are synonymous with basic obedience. Basic skills can be assessed with a practical exercise such as the Canine Good Citizen Test [39]. To pass this test, dogs must be able to sit, stay, and lie down; walk on a loose leash; come when called; accept friendly strangers; sit for petting; and react appropriately to distractions, strange dogs, and other people. Dogs exhibiting basic skills are not aggressive toward individuals or other animals, do not jump on people, and are housetrained. Advanced skills are more complex or specialized tasks that go beyond the level of basic obedience. These tasks require more extensive or advanced training methods, usually under the direction or assistance of an experienced or professional animal trainer.

The third factor is whether a public service, military, or healthcare professional uses the animal to assist in the implementation of a specific public service task or health-related treatment plan. The animal in this case is handled or accompanied by the professional, who is conducting his or her job according to standard or accepted practices. Public service professionals include firefighters, police officers, emergency medical technicians, and other public protection or safety workers. Military professionals include Active Duty service members, reservists, or military contract personnel. Healthcare professionals include physicians, psychologists, social workers, counselors, physical or occupational therapists, and other allied healthcare professionals.

The fourth factor is whether certifications or standards are available to help guide the training or use of the assistance animal. For some categories of assistance animal, certifications and training standards exist, but these have been developed and promulgated by service dog organizations or advocacy organizations for voluntary compliance only. For example, many hospitals and healthcare facilities require that dogs used in their animal visitation programs obtain “certification” to ensure that they are well behaved and have basic obedience skills. Many facilities accept certification by organizations such as Pet Partners (formerly known as the Delta Society) or Therapy Dogs International, but explicit requirements for certification or adherences to a training standard have not been codified into any Federal or state statutes.

The fifth factor addresses whether public access for individuals with an animal is legally protected by Federal or state statute and whether the access is limited or unlimited. Although the laws regarding public access for assistance animals will likely change over time, we believe that including this factor in the revised taxonomy helps to differentiate the functional categories. Furthermore, future policy debates and decisions regarding legal access protections for any category of assistance animal should consider of all five differentiating factors.

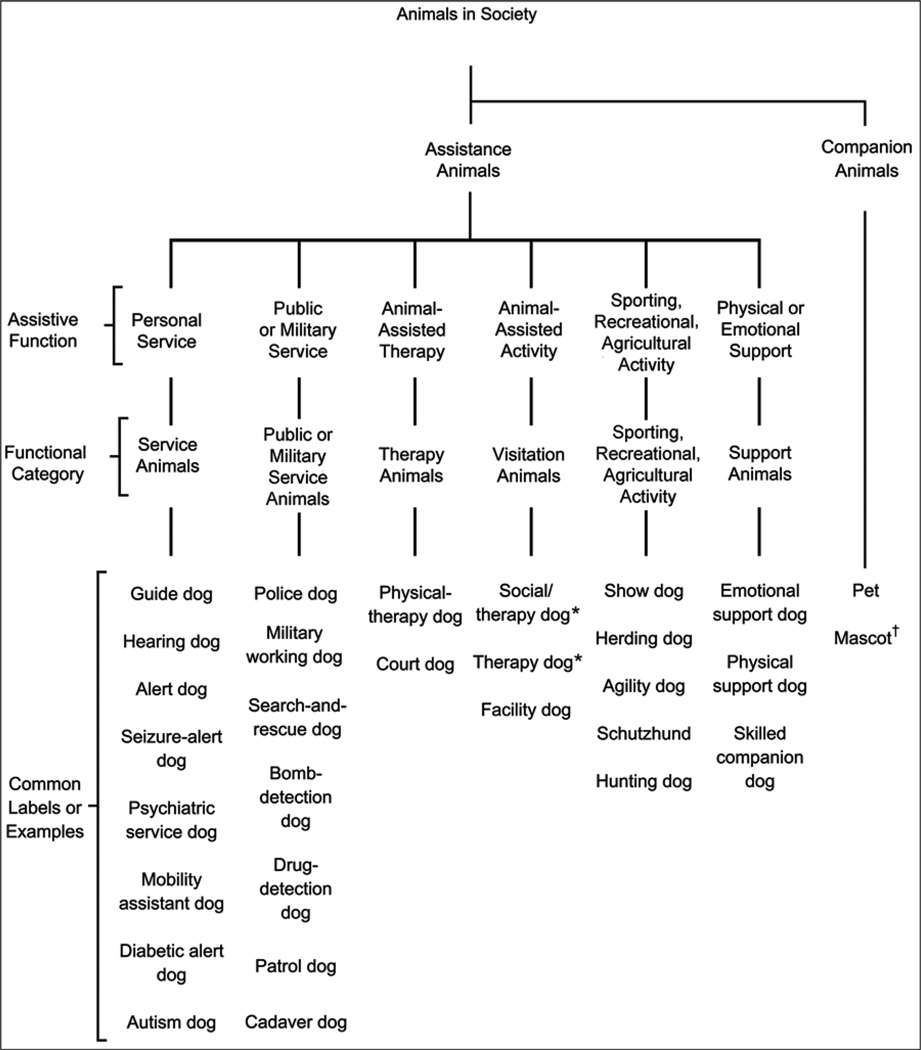

Undoubtedly, there are numerous other features of various categories of assistance animals that are not mentioned or described herein. The Figure illustrates how our proposed taxonomy of the various assistive functions of animals and the corresponding functional categories align with other commonly used labels for assistance animals.

Figure.

Classification of animals in society showing various assistive functions, six major functional categories of assistance animals, and several commonly used labels or examples pertaining to assistance dogs. *Although common, therapy is not preferred label in this functional category. †Animal used for esprit de corps and as morale booster. In military, mascots are official government-owned animals that are placed on orders.

RESULTS: FUNCTIONAL CATEGORIES OF ASSISTANCE ANIMALS

Service Animal

Service animals have been trained to provide work or perform tasks related to an individual’s disability. When accompanied by their handler, who is an individual with a disability, service animals are afforded public access protections. Although standards have been recommended for training and certifying service animals, currently there are no legally recognized standards available. This definition of service animal is consistent with the current ADA.

The individual with a disability is also the primary handler and caregiver of the animal. Indeed, most service dogs are specifically trained to ignore commands given by individuals other than their handler to solidify the bond between the individual and his or her service dog. Within this functional category, other more specific and commonly used labels (e.g., seeing-eye dog, hearing dog,seizure-alert dog, and psychiatric service dog) may reveal an individual’s disability or the tasks the dog can perform; however, consistent with the ADA, the more generic label service animal grants the individual and his or her dog public access without disclosing the individual’s specific disability, if desired [40].

Although the training that a service animal receives varies, most service dogs are trained to perform multiple tasks. Many tasks require advanced training methods. For example, service dogs can be trained to assist individuals with mobility impairments by turning lights on and off, opening doors, and retrieving and carrying items. They also can be trained to assist with laundry and bed making by picking up clothes and pulling or tugging on sheets. A service dog can be trained to alert an individual with hearing impairment to a doorbell or a ringing telephone or safely guide an individual with visual impairment across a street. Additionally, service animals can be trained to assist individuals with psychiatric disorders or mental disabilities, such as panic disorder, schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease, and PTSD. Psychiatric service dogs [41] have been trained to assist an individual with PTSD by alerting the individual of an approaching stranger, surveilling the home prior to the individual entering, or offering a distraction during flashbacks [5]. Dogs that have been trained to assist children with autism may alert caregivers when repetitive behaviors occur or serve as a tether to prevent children from fleeing by going into a “down-stay” position if the child runs [5]. Service dogs can also be trained to alert individuals to impending seizures or panic attacks and assist incapacitated individuals by barking until help arrives, pushing a 911 call button, or alerting a specific individual [42].

Despite the ADA requirement that service animals be trained to perform work or tasks related to a disability, the ADA does not specify or mandate that a service animal be certified or receive any specialized training. Nevertheless, many service dog providers “certify” service dogs that successfully complete their programs, even though the requirements of these programs can vary widely. To protect the safety of the public, handler, and dog, it is important that behavioral and training standards be developed for service dogs. Toward this end, ADI has promoted a set of minimum training recommendations that include the ability to perform at least three tasks, remain in close proximity to the handler at all times when in public, and exhibit no fear responses to noises or other distractions when in public [17].

Currently, Federal and state laws protect the public access rights of individuals with disabilities and their service dogs. Access to any public place is generally allowed; however, there are some exceptions. For example, access with service dogs is not legally protected in churches or in Federal, state, or local government property. Service dogs may also be prohibited when their presence results in changes to normal business practice or when their presence poses health or safety risks. This assessment is made on an individual basis by considering the nature, duration, and severity of risk and whether reasonable modifications will mitigate the risk [23]. This concern extends to the use of service animals by employees in a workplace. Title I of the employment section of the ADA does not require employers to allow employees to bring their service animal to work. Instead, service dogs are considered a reasonable accommodation, one that would not cause undue hardship on the operation of the business [22].

Public Service or Military Animal

Public service or military animals have been trained in advanced skills to provide work or tasks to assist public service or military professionals in performing their duties. Public service or military animals are afforded limited public access protections when on duty with their handler. Standards for training and certifying some types of public service or military animals are available.

Examples of public service or military animals include search-and-rescue dogs, cadaver dogs, police dogs, drug-detecting dogs, and military working dogs. Public service or military animals do not provide skills related to a disability. Their skills are related to public or military service and safety and may include tasks such as helping border guards inspect incoming vehicles, searching a disaster site for living or deceased individuals, or finding a lost hiker. Public service or military animals have specialized skills and require advanced training. For example, detection dogs are trained in sophisticated scent discrimination, and police dogs are trained in skills related to apprehending and controlling suspects.

Public service or military animals work directly with public service or military professionals (i.e., police officers, military personnel, and search-and-rescue professionals) in the performance of their duties. The military and many public service organizations have policies or guidelines that specify training and handling requirements of the service professional prior to working with these animals to assure public safety.

The availability of training and certification standards for public service or military animals depends on the function of the animal, and in some cases, the organization using its services. For example, there are industry-wide minimum training standards for police dogs [43]. The Federal government created the Scientific Working Group on Dog and Orthogonal Detector Guidelines to create recommended guidelines and best practices for the training of detector dogs [44]. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has its own certification protocols for dogs deployed in disaster areas under its purview [45], and the U.S. Army has outlined specific standards for military working dogs and their handlers [46].

There are no explicit Federal public access protections for public service or military animals. In general, access is protected only when the animal is in a location where the handler is on duty and legally present. Some states have created specific statutes. New Hampshire, for example, has granted public access protections to search-and-rescue dogs when they are performing their duties or traveling to and from the sites where they are performing their duties [47], and California has protected access under these circumstances for police dogs, firefighters’ dogs, and search-and-rescue dogs [48]. Otherwise, off-duty public service or military animals are regarded as pets when considering public access protections.

Therapy Animal

Therapy animals have been trained in either basic or advanced skills to assist a healthcare or allied healthcare professional within the scope of a therapeutic treatment plan. Therapy animals are not afforded public access protections; permission to access public or private property must be sought on a case-by-case basis. Some recommended standards for training and certifying therapy animals are available, but these are not codified.

Physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, and other professionals may use dogs to help their clients obtain treatment goals. For example, a physical therapist may use a therapy dog to encourage a child with muscular dystrophy to throw a ball for the dog to retrieve or have a patient brush a dog to improve his or her motor skills [49]. Social workers and psychologists may use therapy dogs to create an environment of trust and acceptance during consultation or psychotherapy [7, 50–51] or to encourage a child’s compliance in a behavioral modification program [52].

The term therapy is included in this category label to imply that the animal is used for animal-assisted therapy [8] as part of a medical or allied healthcare treatment [6–7]. This further emphasizes that the therapy is conducted under the guidance and responsibility of a healthcare or allied healthcare professional as part of a formal treatment plan. As a professional activity, the treatment is conducted according to accepted practices and ethical principles, which includes adequate training of the professionals to work with the animal.

The minimum necessary skill requirements for therapy animals are basic, including obedience and socialization. For example, a dog used to provide emotional support to a child during a psychotherapy session does not need to perform complex tasks but might be required to sit still for long periods and accept frequent petting. In some cases, although not required, a therapy dog may perform advanced skills, such as bracing to assist an individual with mobility impairment in standing during physical therapy.

Some training standards or certifications for therapy animals are available. For example, the U.S. Army has established specific health and behavioral requirements for animals used in what was referred to as animal-facilitated therapy [53]. Many of the requirements for therapy animals are similar to or overlap with standards developed by Pet Partners and Therapy Dogs International [8]. Many hospitals and medical facilities have policies or protocols that require minimum standards such as the Canine Good Citizen certification [4].

There are no Federal protections for public access pertaining to therapy animals. Kansas is the only state that specifically addresses public access issues pertaining to therapy animals. Using a definition of therapy animal that is similar to that presented herein, the Kansas statute grants professionals using professional therapy dogs the same public access protections as individuals with service animals [54]. Some have advocated expanding legal access protections to include therapy dogs in unique situations where their services are needed, such as disaster sites [5].

Visitation Animal

Visitation animals are trained in basic skills to provide comfort and support to individuals through companionship and social interaction primarily in nursing homes, hospitals, and schools. Visitation animals are not afforded public access protections; permission to access public or private property must be sought on a case-by-case basis. Standards for training and certifying visitation therapy animals are available but not universally accepted.

We excluded the term therapy in this category label in deference to existing and widespread acceptance of the distinction between animal-assisted therapy and animal-assisted activity [8, 53]. The present taxonomy uses the modifier visitation for this functional category to help distinguish animals used in hospital or nursing home visitation programs from therapy animals used by healthcare and allied healthcare professionals as part of a professional therapy activity. This vocabulary should minimize much of the existing confusion.

The skills performed by visitation animals are not specific to an individual’s disability. Although only basic obedience and socialization skills are necessary, the animal must be well behaved in a variety of settings and with a variety of people. This requires an ability to accept prolonged petting and attention by individuals of various ages, appearances, and ethnic backgrounds and familiarity with items frequently found in the particular setting, such as intravenous poles and wheelchairs in hospitals and nursing homes.

Visitation animals are not required to be accompanied by healthcare or allied healthcare professionals. Although the animals can be frequent visitors in nursing homes, hospitals, and other facilities, they are typically accompanied, handled, and owned by community volunteers.

There are established and well-accepted certification programs pertaining to visitation dogs, even though they are not required by Federal or most state statutes. Several organizations, such as Therapy Dogs International and Pet Partners, have developed thorough training protocols and testing standards that lead to certification. For example, one organization certifies dogs and their owners as visitation animal teams based on a skills and aptitude test. This test requires that the team demonstrate the dog’s basic skills such sit, down, and stay. The ability to accept large crowds of people, being bumped by objects, being petted by multiple people at a time, and taking treats appropriately is also required [8]. Most hospitals, nursing homes, and other facilities accept these certifications, but specific requirements may vary.

Visitation animals are not typically granted public access. Some argue that visitation animals should have limited public access, especially when being taken to and from appointments and when traveling to distant locations to provide services [5].

Sporting, Recreational, or Agricultural Animal

Sporting, recreational, or agricultural animals have been trained in basic or advanced skills to provide work or tasks associated with competition, transportation, farm work, or recreation. Sporting, recreational, or agricultural animals are not afforded public access protections. Standards for training and certifying these animals are available and usually associated with specific sporting or show organizations.

Sporting, recreational, or agricultural dogs may be trained to stand for inspection by a show judge, perform agility tasks, pull a sled, track a scent, or herd other animals. Hunting dogs, herding dogs, agility dogs, dock diving dogs, fly-ball dogs, and Frisbee dogs are all examples. Although many of these skills require advanced, complex, or rigorous training methods, the work or tasks performed do not benefit an individual with a disability, and the dogs do not work with healthcare or allied healthcare professionals as part of a treatment or therapy program. Sporting, recreational, and agricultural animals are usually trained by professional trainers or their owners and work for their owners or appointed handlers.

Certifications and standards for some types of sporting, recreational, and agricultural animals are available by their respective organizations, but they usually are not required except when the animal participates in competitions. Organizations like the American Kennel Club have developed standards and certifications for their conformation, herding, and agility competitions. Similarly, sled dog organizations provide certifications for sled dogs (e.g., Alaskan Malamute Club of America).

Sporting, recreational, and agricultural animals do not have public access protections. Because legal public access protections for service animals and, to a limited extent, other categories of assistance animals originated with the desire to accommodate individuals with disabilities, access protections for these dogs are not likely to be considered imperative.

Support Animal

Support animals provide physical, psychiatric, or emotional support to individuals in need primarily in the home. Support animals with or without basic or advance skills are afforded protections for access to private residences and public housing projects. There are no standards for training and certifying support animals. Common labels used for dogs include emotional support dogs, social therapy dogs, skilled companions, and home-help dogs. Although pets may provide similar levels of support, there must be a nexus between the owner’s disability and the presence of the animal for it to be considered a support animal.

The support, aid, or comfort provided by support animals must be directly related to an individual’s disability or need. The animal may assist an individual in activities of daily living or perform more complex tasks such as retrieving items or reminding the owner to take medications, but the animal need not be trained to perform specialized tasks. The mere presence of the animal may be sufficient.

There are no certifications or training standards available for support animals nor do housing regulations require or specify any level of training.

In general, support animals serve a direct function to individuals in their residences. Thus, support animals have received limited protections under Federal regulations to reside in both public and private housing [24]. The definition of support animal herein is consistent with Federal housing regulations in which the more specific label emotional support animal often appears. It is important to note that Federal housing regulations define the term support broadly to include emotional, psychiatric, or physical assistance. Thus, the term support in the functional category is already codified and widely accepted; however, additional modifiers that specify the type or nature of support (i.e., physical, psychiatric, or emotional) were deemed to be unnecessary in the present taxonomy. A more generic category label serves to identify a support animal for the purposes of gaining access to residential facilities without revealing an individual’s disability or emotional needs if desired.

Under HUD regulations, an animal qualifies as a support animal if an individual has a disability, an animal is needed to assist with a disability, and the individual demonstrates that there is a relationship between the disability and the assistance that the animal provides [24]. Proof of need is most easily conveyed with a letter from the individual’s physician describing the necessity of the animal to the person’s specific disability, but this is not legally required.

DISCUSSION

Multiple reasons exist for the development and broad acceptance of a standardized and comprehensive taxonomy for animals in our society. Aside from their role as invaluable companions, dogs especially are gaining increasing importance and recognition for their service to humankind in a variety of personal, social, occupational, and health-related pursuits. Whereas the benefits of some of these services are obvious and do not require validation, other purported benefits are supported only by anecdotal information. More rigorous scientific evaluations will be required before many of these benefits are widely accepted and supported by policy makers, government and public service agencies, and healthcare providers. The first step in this process is the establishment of an effective taxonomy that sufficiently defines and differentiates the categories of dogs across various assistance, support, and companionship roles. We believe the revised taxonomy offered herein works well for dogs, and additional, slightly modified, versions would work well for other animals (e.g., miniature horses, cats, and primates) that serve assistive or therapeutic functions. This taxonomy is also consistent with the revised Department of Defense Human-Animal Bond Principles and Guidelines (TB MED 4), which is expected to be released in 2013.* Likewise, we have attempted to align this taxonomy with the vocabulary recommended by others in the field where possible.

Society’s increasing recognition and acceptance of the wide range of assistive functions that dogs can provide is a positive development, perhaps reflecting our long-time collective concern for and desire to help individuals with physical and emotional challenges and the important roles that canines have played in the evolution of mankind. Indeed, the benefits of dog assistance are being tried and tested in many different novel applications, the breadth of which is seemingly limited only by the dedication and creativity of the professionals involved. Currently, our legal system protects the public access rights of individuals with disabilities when accompanied by a service animal. Despite these protections, the laws or regulations do not consistently or clearly define service animal, specify the type of training or skills required, or list the inclusionary or exclusionary criteria that might apply. This inconsistency, frequently coupled with a lack of awareness, causes confusion for many business and property owners and creates obstacles for individuals with service animals. These problems are likely to be exacerbated with the expanding therapeutic uses of animals. Some advocates have already called for expanded public access protections for dogs in other therapeutic settings [5].

CONCLUSIONS

As the interest in and demand for assistance animals increases, dogs and other animals are being trained for multiple assistive functions without adequate guidelines and with little, if any, oversight. The potential risks associated with insufficiently trained animals or animals that are not properly socialized to interact safely with the public are likely to be exacerbated by the rapid growth in this emerging industry. Although some organizations are attempting to establish guidelines for training and certification, any standard will be difficult to promote and enforce without a universally accepted taxonomy on which policy and practice can be built.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding/Support: This material was unfunded at the time of manuscript preparation.

Additional Contributions: We thank COL Perry R. Chumley, DVM, MPH, Diplomate ACVPM, Chief, Human-Animal Bond programs, Department of Defense Veterinary Service Activity, Office of the Surgeon General, and Margaret Glenn, EdD, CRC, Associate Professor of Rehabilitation Counselor Education, Department of Counseling, Rehabilitation Counseling, and Counseling Psychology, West Virginia University, for their thoughtful comments and contributions to previous drafts of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADA

Americans with Disabilities Act

- ADI

Assistance Dogs International

- HUD

Department of Housing and Urban Development

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

Footnotes

Chumley, P. R. (Human-Animal Bond Programs, Department of Defense Veterinary Service Activity, Office of the Surgeon General, Washington, DC). Conversation with: Oliver Wirth (Health Effects Laboratory Division, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV). 2012 Oct 12.

Author Contributions

Literature review, initial outline, and drafting of manuscript: L. Parenti, A. Foreman.

Conceptualization of taxonomy, figures and tables, and final draft of manuscript: B. J. Meade, O. Wirth.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

This article and any supplementary material should be cited as follows:

Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, Wirth O. A revised tax-onomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013; 50(6):745–56.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson PE. The powerful bond between people and pets. Westport (CT): Praeger; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chumley PR. Historical perspectives of the human-animal bond within the Department of Defense. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:18–20. [PMID: 22388676] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical per-spective. In: Fine AH, editor. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2010. pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arkow P. Animal-assisted therapy and activities: A study, resource guide and bibliography for the use of companion animals in selected therapies. 10th ed. Stratford (NJ): P. Arkow; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ensminger JJ. Service and therapy dogs in American society: Science, law and the evolution of canine caregivers. Springfield (IL): Charles C. Thomas; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck AM, Katcher AH. A new look at pet-facilitated therapy. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984;184(4):414–21. [PMID: 6365867] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruger KA, Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: Definitions and theoretical foundations. In: Fine AH, editor. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2010. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pet Partners [Internet] Bellevue (WA): Pet Partners; 2013. [cited 2012 Jun 10]. updated 2013; Available from: http://www.petpartners.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills JT, 3rd, Yeager AF. Definitions of animals used in healthcare settings. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:12–17. [PMID: 22388675] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cusak O. Pets and mental health. New York (NY): Haworth Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naderi S, Miklósi A, Dóka A, Csányi V. Co-operative interactions between blind persons and their dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2001;74(1):59–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(01)00152-6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rights of Blind and Physically Disabled Persons, Stat. D.C. Code Ann. § 7-1009 (2012)

- 13.Bergin B. The smartest dog: The selection, training and placement of service dogs. Santa Rosa (CA): Assistance Dog Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livestock Disease Control, Stat. Mass. Stat. § 129-39F (2002).

- 15.White Cane Law, Stat. Ill. Stat. § 775-3 (2003)

- 16.Ohio Rev. Code § 955.011 (1998). Available from: http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/955.011

- 17.Assistance Dogs International [Internet]. Standards. Santa Rosa (CA): Assistance Dogs International; 2013. [cited 2012 Aug 30]. Available from: http://www.assistancedogsinternational.org/standards/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine AH, editor. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaJoie KR. An evaluation of the effectiveness of using animals in therapy [dissertation] Louisville (KY): Spalding University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stedman TL, editor. Stedman’s medical dictionary. 26th ed. Baltimore (MD): Williams & Wilkins; 1995. Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary. 10th ed. Springfield (MA): Merriam-Webster Inc; 1997. Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Stat. 42 U.S.C. § 12186 et seq. (2010).

- 23.Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability in State and Local Government Services, Stat. 28 C.F.R Part 35, Appendix A (2011).

- 24.Pet ownership for the elderly and persons with disabilities. Fed Regist. 2008;73:63834–63838. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability in Air Travel, Stat. 14 C.F.R. pt. 382 (2003).

- 26.Act DD. 1992 (Cth) s 9 (Austl.).

- 27.Guide Animal Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, C 177 (Can.).

- 28.Accessibility Standards for Customer Service, O. Reg 429/07 (Can.).

- 29.Dog Control Amendment Act 2006 s 2 (N.Z.).

- 30.Mass. Gen. Laws, Stat. 129 § 39F (2002).

- 31.Sak v. City of Aurelia. W.D. Iowa 20112011.

- 32.Storms v. Fred Meyer Stores, Inc. Wash. Ct. App. 20052005.

- 33.Koda N, Shimoju S. Public knowledge of and attitudes toward accessibility of assistance dogs for physically impaired people in Japan. Asian J Disable Soc. 2008;7:74–85. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dilley S. Admit my guide dog, says blind journalist Sean Dilley. BBC News. 2011 Apr 27; [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams K, Rice S. A brief information resource on assistance animals for the disabled [Internet] Beltsville (MD): Animal Welfare Information Center U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2011. [cited 2012 May 15]. updated 2011 Sep 19; Available from: http://www.nal.usda.gov/awic/companimals/assist.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serpell JA. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. J R Soc Med. 1991;84(12):717–20. doi: 10.1177/014107689108401208. [PMID: 1774745] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel JM. Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: the moderating role of pet ownership. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58(6):1081–1086. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.6.1081. [PMID: 2391640] http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cain AO. Pets and the family. Holist Nurs Pract. 1991;5(2):58–63. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199101000-00012. [PMID: 1984018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volhard J, Volhard W. The canine good citizen: Every dog can be one. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Howell Book House; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duncan SL. APIC State-of-the-Art Report: the implications of service animals in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28(2):170–180. [PMID: 10760225] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0196-6553(00)90025-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tedeschi P, Fine AH, Helgeson JI. Assistance animals: Their evolving role in psychiatric service applications. In: Fine AH, editor. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2010. pp. 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirton A, Winter A, Wirrell E, Snead OC. Seizure response dogs: evaluation of a formal training program. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(3):499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.05.011. [PMID: 18595778] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.United States Police Canine Association [Internet]. Certification. Springboro (OH): USPCA; 2010. [cited 2012 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.uspcak9.com/html/certification.html. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scientific Working Group on Dog and Orthogonal Detector Guidelines [Internet] Miami (FL): SWGDOG; 2013. [cited 2012 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.swgdog.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 45.Disaster search canine readiness evaluation process. Washington (DC): FEMA; 1999. [cited 2012 Sep 11]. Federal Emergency Management Agency [Internet] updated 1999 Jul 20. Available from: http://leerburg.com/pdf/crep_bdy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. Department of Army, Stat. Reg. 190-12, Military Working Dog Program (2007)

- 47.Hearing Ear Dogs, Guide Dogs, Service Dogs, and Search and Rescue Dogs. Stat. N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. 1996;167-D:3. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blind and Other Physically Disabled Persons, Stat. Cal. Ann. Civ. Code § 54.25 (2010).

- 49.Gammonley J. Animal-assisted therapy: Therapeutic interventions. Renton (WA): Delta Society; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corson SA, Corson EO, Gwynne PH, Arnold LE. Pet-facilitated psychotherapy in a hospital setting. Curr Psychiatr Ther. 1975;15(15):277–86. [PMID: 1237389] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mason MS, Hagan CB. Pet-assisted psychotherapy. Psychol Rep. 1999;84(3 Pt 2):1235–1245. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1235. [PMID: 10477944] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis KD. Therapy dogs: Training your dog to reach others. 2nd ed. Wenatchee (WA): Dogwise Pub; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.U.S. Department of Army. Stat. Technical Bulletin Med. No. 4, DOD Human-Animal Bond Principles and Guide-lines (2003)

- 54.Physically Disabled Persons, Stat. Kan. Ann. Stat. § 39-1110 (2003)