Dear Editor,

Nucleophosmin (NPM1) is a nucleolar protein implicated in ribogenesis, centrosome duplication and stress response.1 NPM1 is mutated in ~30% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients.2 Heterozygous mutations involve few base duplications or insertions in the gene's last exon. In all cases, the reading frame is altered and mutated NPM1 (NPM1c+) loses Trp288 and/or Trp290 and acquires a C-terminal nuclear export signal (NES).2 These alterations unfold the NPM1c+ C-terminal domain3,4 with nucleolar displacement because of impaired nucleic acid binding.5 Furthermore, the additional NES drives the stable translocation of NPM1c+ in the cytosol2 and, due to hetero-oligomerization, also of the majority of NPM1. Only a residual, but detectable, fraction of NPM1 is nucleolar, which may be necessary for blasts' survival.6

A potential approach to treatment of AML with NPM1 mutation may be developing drugs that displace NPM1 from the nucleoli, causing nucleolar stress and apoptosis.6 Given their paucity of nucleolar NPM1, blasts should be more sensitive to such treatment than healthy cells.

Recently we showed that NPM1 binds G-quadruplexes,7 including those at nucleolar rDNA, and that the G-quadruplex ligand TmPyP4 dissociates NPM1 from the nucleoli in NPM1+/+ OCI-AML2 leukemia cells.5 Here we compare the effect of TmPyP4 treatment on a AML cell line carrying the most common NPM1 mutation (OCI-AML3) with the one carrying only wild-type protein (OCI-AML2). While in OCI-AML2 NPM1 only localizes in the nucleoli (Supplementary Figure S1),5 in OCI-AML3 it shows a diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (Supplementary Figure S2). Upon treatment with 50 μM TmPyP4, after 48 h, NPM1 is completely displaced from the nucleoli in both OCI-AML25 and OCI-AML3 cells (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). Also, fibrillarin and nucleolin are displaced (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2) and, while NPM1 and nucleolin remain stable, fibrillarin is completely degraded, as confirmed by western blot analysis (not shown).

Chronic NPM1 depletion in HeLa cells alters nucleolar morphology.8 However, acute displacing of NPM1 with TmPyP4 does not seem to have major effects on nucleolar appearance, after 48 h of treatment, in both cell lines. Although the total number of nucleoli is reduced by 15%, the nucleolar fibrillar centre (FC), dense fibrillar component (DFC) and granular component (GC) are still detectable, with only the DFC and GC appearing more interspersed (Supplementary Figure S3). OCI-AML3 cells have larger nucleoli than OCI-AML2, but their size drops upon treatment (Supplementary Figure S3).

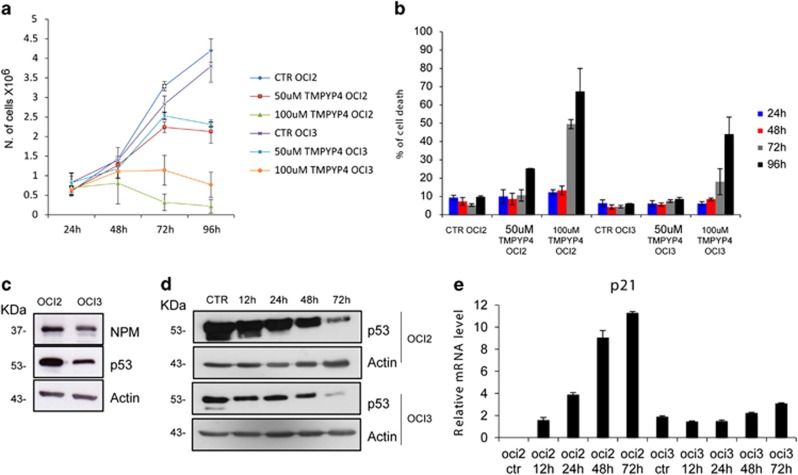

Evaluation of the effect of TmPyP4 on cell viability shows that, at 50 μM dose, the drug is modestly toxic in both OCI-AML25 and OCI-AML3 cells, with growth arrest after 72 h of treatment (Figure 1a). Accordingly, no changes in the cell cycle are observed (not shown). After 96 h of treatment, cell death increases in OCI-AML2 but not in OCI-AML3 cells (Figure 1b). At the higher (100 μM) dose, TmPyP4 induces significant death in OCI-AML2 cells,5 while OCI-AML3 cells are considerably more resistant (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Viability of OCI-AML2 and OCI-AML3 cells, untreated (CTR) and treated with TmPyP4 50 or 100 μM at the indicated time points (hours). (b) Percentage of cell death for OCI-AML2 and OCI-AML3 cells after treatment, as described above. (c) Western blot analysis of OCI-AML2 and OCI-AML3 cells, using antibodies against nucleophosmin (NPM1), p53 and β-actin as a loading control. The corresponding molecular weights are indicated on the left. (d) Western blot analysis of OCI-AML2 and OCI-AML3 cells treated with 100 μM TmPyP4 for the indicated time points (hours) using antibodies against p53 and β-actin as a loading control. (e) Real-time PCR of RNA extracted from OCI-AML2 and OCI-AML3 cells, untreated (CTR) or treated with 100 μM TmPyP4 for the indicated time points (hours) using primers for human p21

NPM1c+ is known to affect the p53 pathway in multiple ways1 and indeed OCI-AML3 cells have lower p53 levels than OCI-AML2 (Figure 1c). Upon treatment with TmPyP4, p53 levels decrease in both cell lines (Figure 1d). However, TmPyP4 seems to activate p53 in OCI-AML2 cells, since levels of its trascriptional target p21 steadily increase. Conversely, no effect on p21 levels is seen in OCI-AML3 cells (Figure 1e). Thus, a p53-dependent death pathway may be activated in cells with wild-type NPM1 only, but not in those with NPM1c+. The lower sensibility to TmPyP4 and the absence of p53 activation in OCI-AML3 cells may correlate with the ability of NPM1c+ to promote cytoplasmic delocalization and degradation of the tumor suppressor p14ARF.1

In conclusion, we suggest that acute NPM1 nucleolar delocalization, driven by TmPyP4, is not highly noxious to AML cells. TmPyP4-induced toxicity in cells bearing only wild-type NPM1 appears to be dependent on p53 activation and is not necessarily correlated with NPM1 location. Thus, the NPM1 nucleolar starvation strategy may not be indicated for treating AML with mutated NPM1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AIRC grant IG2011-11712 to LF.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Supplementary Material

References

- Colombo E, et al. Oncogene. 2011. pp. 2595–2609. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Falini B, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005. pp. 254–266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grummitt CG, et al. J Biol Chem. 2008. pp. 23326–23332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Scaloni F, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010. pp. 5447–5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chiarella S, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013. pp. 3228–3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Falini B, et al. Blood Rev. 2011. pp. 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Federici L, et al. J Biol Chem. 2010. pp. 37138–37149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Amin MA, et al. Biochem J. 2008. pp. 345–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.