Abstract

Replacement of dysfunctional or dying photoreceptors offers a promising approach for retinal neurodegenerative diseases, including age-related macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa. Several studies have demonstrated the integration and differentiation of developing rod photoreceptors when transplanted in wild type or degenerating retina; however, the physiology and function of the donor cells are not adequately defined. Here, we describe the physiological properties of developing rod photoreceptors that are tagged with GFP driven by the promoter of rod differentiation factor, Nrl. GFP-tagged developing rods show Ca2+ responses and rectifier outward currents that are smaller than those observed in fully developed photoreceptors, suggesting their immature developmental state. These immature rods also exhibit hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) induced by the activation of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels. When transplanted into the subretinal space of wild type or retinal degeneration mice, GFP-tagged developing rods can integrate into the photoreceptor outer nuclear layer in wild-type mouse retina, and exhibit Ca2+ responses and membrane current comparable to native rod photoreceptors. A proportion of grafted rods develop rhodopsin-positive outer segment-like structures within two weeks after transplantation into the retina of Crx-knockout mice, and produce rectifier outward current and Ih upon membrane depolarization and hyperpolarization. GFP-positive rods derived from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells also display similar membrane current Ih as native developing rod photoreceptors, express rod-specific phototransduction genes, and HCN-1 channels. We conclude that Nrl-promoter driven GFP-tagged donor photoreceptors exhibit physiological characteristics of rods and that iPS cell-derived rods in vitro may provide a renewable source for cell replacement therapy.

Introduction

Retinal neurodegenerative diseases represent a heterogeneous group of pathologies, yet photoreceptor cell death is a common feature in many of these disorders (http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/retnet/). Gene discovery has guided successful gene therapy approaches 1-3and targeted pharmacologic interventions 4-6 for delaying or treating retinal dysfunction. However, gene and drug therapy strategies require the presence of sufficient numbers of viable and functional photoreceptors. No treatment is currently effective after photoreceptors are lost.

Cell transplantation offers a promising approach for the treatment at late stages of retinal degenerative diseases. Bone-marrow derived stem cells were initially tested for cell-based therapy 7-10. Subsequently, committed but immature rod photoreceptors from the postnatal day (P)3-5 mouse retina were shown to be optimal for transplantation and integration in the murine retina 11. In these experiments, the location and differentiation of the transplanted cells were determined using developing photoreceptors from Nrlp-eGFP mice expressing GFP in rods under control of the promoter of neural retina leucine zipper transcription factor Nrl that is a key regulator of rod cell fate 12, 13. More recently, retinal progenitors and rod photoreceptors have been derived from embryonic stem (ES) or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells 14-20 and shown to incorporate into the mouse retina and express photoreceptor-specific proteins 21-23. Functional analyses have been conducted after transplantation in murine models of degeneration, primarily by electroretinography (ERG) and/or measurements of pupillary reflex, indicating some improvement in visual function 11, 22, 23. However, neither method reflects the direct contribution of transplanted cells and/or their indirect impact on the residual endogenous photoreceptor population. Although a couple of studies have investigated the functional state and physiology of the donor cells 19, 24, cellular function has not been compared before and after transplantation.

Rod photoreceptors respond to light, activating the phototransduction pathway. In the dark, rods are depolarized because of high cGMP concentrations that keep cGMP-gated sodium channels open. Membrane depolarization increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels 25-27, which induce glutamate release from pre-synaptic terminals. The capture of photons results in isomerization of 11-cis to all-trans retinal attached to opsin, leading to the closure of cGMP-gated sodium channels and induction of membrane hyperpolarization. In vertebrates, functional rod photoreceptors express hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated type 1 (HCN-1) channels 28-32, which function as high-pass filters 33, 34 augmenting high frequency responses 35. Thus, ion channel activity is a reliable indicator of photoreceptor functionality and can provide direct information on donor photoreceptors in cell replacement paradigms.

Here, we apply physiological methods to evaluate the intrinsic functional properties of donor cells transplanted in the retina. We record Ca2+ responses and cell membrane current of developing rods from Nrlp-eGFP mice, before and after transplantation in retinal degeneration mouse models. We further apply the same approach to examine developing rods that are derived from iPS cells established from Nrlp-eGFP mice. Our studies suggest that transplanted rod precursors undergo functional maturation and that retinal cells derived from differentiation of iPS cells are comparable to rod precursors.

Material and Methods

Animals

All experiments using mice were approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Eye Institute, National Institute of Health and RIKEN CDB Animal Experiment Committee. C57BL/6 Cr Slc mice were purchased from Nihon Slc (Shizuoka, Japan) or Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). Crx-knockout (Crx-KO) mice36 were a generous gift of Dr. Takahisa Furukawa. Animals were maintained under standard laboratory conditions (18-23°C, 40-65% humidity, 12 h light-dark cycle) with free access to food and water throughout the experimental period.

Retinal Cell Transplantation

The retinas from postnatal day (P)5 Nrlp-eGFP mice were treated with Accutase (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 15 min. After gentle pipetting, the dissociated cells were re-suspended in HBSS-glucose (50 mg/l) at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/μl. Two μl cell suspension was injected in the sub-retinal space of the recipient mouse using Femtojet (Eppendorf, Germany). Two weeks after transplantation, eyes were fixed for immunostaining or dissected for Ca2+ imaging and electrophysiology.

Generation of iPS cells from Nrlp-eGFP mice

Fibroblasts from Nrlp-eGFP transgenic mice were infected with Sendai virus vectors carrying Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc genes (DNAVEC, Japan) 37 and then seeded onto SNL feeder cells (Cosmo Bio, Japan). After three weeks culture (in DMEM / 15% FBS / 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate / 0.1 mM NEAA / 0.1 mM 2-ME supplemented with 1,000 U/ml LIF), ES-like colonies were picked and transferred onto fresh SNL feeder layer. After three passages, the cells were cultured on gelatin-coated dishes.

Cell Culture

Mouse ES/iPS cells (Rx knock-in GFP ES line mESRx+; Nrlp-eGFP transgenic iPS line) were maintained in GMEM / 10% FBS / 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate / 0.1 mM NEAA / 0.1 mM 2-ME supplemented with 1,000 U/ml LIF, 3 mM CHIR99021, 1 mM PD0325901 on gelatin-coated dishes. Cells were passaged with 0.25% trypsin-1mM EDTA. For retinal cell differentiation by modified SFEB/DLFA method15, Dkk1 (100 ng/ml, during days 0-5, R&D Systems, CA), LeftyA (500 ng/ml, during days 0-5, R&D Systems), 5% FBS (during days 3-5, JRH Biosciences, KS), activin-A (10 ng/ml, during days 4-5, R&D Systems) and a γ-secretase inhibitor, N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-Lalanyl] -S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT, 10 mM, during days 9-11, Calbiochem, CA) were added to the differentiation medium (GMEM, 5% knockout serum replacement (KSR; GIBCO, CA), 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 0.1 mM 2-ME). On day 12, the medium was changed to serum-free medium (70% DMEM, 30% F12) supplemented with B-27 (Invitrogen, CA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. For photoreceptor differentiation, DAPT (10 mM, during days 12-35), aFGF (50 ng/ml, during days 16-24, R&D Systems), bFGF (10 ng/ml, during days 16-24, R&D Systems), taurine (1 mM, during days 16-35, Sigma), sonic hedgehog (Shh, 3 nM, during days 16-35, R&D Systems) and retinoic acid (RA, 500 nM, during days 16-35, Sigma) were added to the medium.

Intracellular Ca2+ imaging

For [Ca2+]i measurements, cells were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-AM (Molecular Probes, CA) for 30 min at 37°C. Culture medium was then changed to recording solution containing 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, and 10 mM D-glucose. Cells were incubated for 15 min for complete hydrolyzation of the acetoxymethylester of Fura-2-AM. For excitation of Fura-2, cells were sequentially irradiated with 340- and 380-nm wavelength light. Emission signals were detected through a 535/55 nm band-pass filter. Images were acquired at fixed intervals with Acquacosmos imaging system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) using a 10× objective (S Fluor, Nikon, Japan). [Ca2+]i was calculated from image data, as described in previous studies38. During the experiments, cells were treated with 100 μM glutamate or 80 mM KCl.

Electrophysiology

Retina was flattened on cellulose filters (0.22 μm GSWP, Millipore, MA) and sectioned using a custom-made tissue slicer (ST-20-S, Narishige, Japan) at 150 μm thickness. Sliced retinas were placed at the center of a recording chamber slide and immobilized using a U-shaped platinum weight bridged by fibers. The chamber was perfused with oxygenated and warm (at 37°C; TC-324B, Warner Instrument, CT) extracellular solution containing 23 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 120 mM NaCl, 3.1 mM KCl, 6 mM glucose, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, and 0.004% phenol red. Retinal slides were not dark-adapted. Recordings were obtained with Multiclamp700B amplifier and pClamp10 software (Axon Instruments, CA). Cell capacitive current was cancelled, and series resistance was compensated for by the above system. Electrode solution contained 135 mM K-gluconate, 10 mM HEPES, 3 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 0.3 mM GTP, 10 mM Alexa594, titrated to pH7.6 with KOH. Pipette resistance ranged from 12 to 17 MΩ. Retinal cells were voltage-clamped with patch clamp technique in the whole-cell mode.

Tissue Fixation and Processing

Eyes were enucleated and placed in fixative (SUPER FIX; KURABO, Osaka, Japan) at 4°C overnight. After automatic fixation (Exelsior, ThermoFisher co., UK), eyes were embedded in paraffin (P3683, Sigma, MO). Paraffin blocks were sectioned at 10 μm thickness using the auto slide preparation system (AS-200, KURABO, Japan). Before immunostaining, the sections were treated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (GIBCO, CA) for 15 min at 37°C. Cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes on ice.

For immunohistochemistry, slides were incubated with blocking solution containing 5% goat serum in PBS for 1 hr at room temperature, and then incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibody (mouse anti-rhodopsin at 1:1000, Chemicon, CA; rabbit anti-GFP at 1:500, Abcam, UK; rat anti-GFP at 1:500, Nacalai, Japan; rabbit anti-HCN-1 at 1:500, Abcam, UK; rabbit anti-recoverin at 1:1000, Chemicon, CA) containing 1% goat serum in PBS. The following morning, samples were washed with PBS-0.05% Tween20 (PBS-T) and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with secondary antibody (anti-mouse/rabbit/rat IgG conjugated with Cy2/Cy3/Cy5 at 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenyindole (DAPI at 1:1000; Sigma, St Louis, MO) containing 1% goat serum in PBS. After washing with PBS-T, samples were mounted in FluoSave reagent (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), and fluorescent images were acquired with fluorescence (BZ9000, KEYENCE, Japan) or confocal microscope (Radiance 2100; BIORAD, Richmond, CA).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from cultured cells, sorted cells or retinal tissue. Cells or tissue were lysed in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA). RNA was extracted with chloroform, precipitated with isopropyl alcohol, washed with 75% ethanol and air-dried briefly. RNA pellet was resuspended in RNase-free water and reverse-transcribed with first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (GE Healthcare, PA). The resulting cDNA was amplified with gene-specific primers (listed in Supplemental Table 1). PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel and detected under UV illumination. Real-time PCR analysis was performed using StepONE plus (Applied Biosystems, CA).

Fluorescence activated cell-sorting (FACS) analysis

Retinal tissue was dissociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (GIBCO, CA) for 5 min. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in a solution containing propidium iodide (5μg/ml) and 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Cells were kept on ice and filtered through a round-bottom tube with cell-strainer cap (BD Falcon, CT) before FACS analysis. Cells were sorted and analyzed using BD FACSAria™II (BD Bioscience, NJ). FACS was also used to purify GFP-tagged photoreceptors, derived from iPS cells.

Transcript level expression profiles

The mRNA expression profiles of flow-sorted Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells, purified at various developmental stages, were obtained using Affymetrix mouse exon arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), imported in .CEL format into Partek Genomics Suite (Partek, St. Louis, MO), and summarized using extended meta probesets and Robust Multichip Average (RMA) normalization39. Gene, exon and transcript annotations were added to the extended probesets using Partek’s “add annotation” feature based on probeset IDs. Probesets having no annotation were filtered out. The annotated probesets are grouped by RefSeq transcript IDs and the average intensity value for each transcript ID was calculated as a mean of the intensities of all probesets targeting the transcript. Based on the intensity value distribution of transcripts, transcripts with mean intensity less than 3.0 at all time-points were filtered out, thus yielding a spreadsheet of transcript isoform level expression profiles based on annotated extended probesets covering 15 time-points of mouse retinal development and aging.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t tests and, for multiple comparisons, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey’s tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Native rod photoreceptors show Ca2+ responses and membrane currents upon membrane depolarization and hyperpolarization

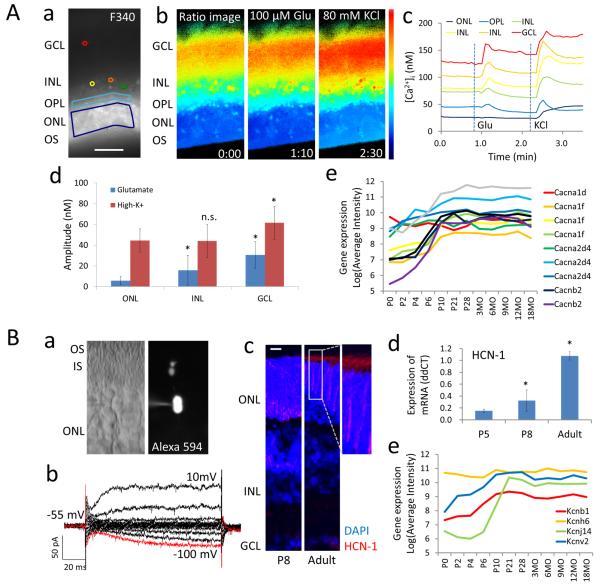

To study the neural activity of native rod photoreceptors, we first performed intracellular Ca2+ imaging of retinal cells in acute slice culture preparations of intact wild type retina at 6 weeks of age (Figure 1A, Supplemental Online Video 1). Retinal slices were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 (Figure 1A, panel a). A ratio image was obtained between the fluorescence induced by 340 nm and 380 nm light (Figure 1A, panel b). [Ca2+]i was estimated in the retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner nuclear layer (INL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and outer nuclear layer (ONL) (Figure 1A, panel c). In the ONL, photoreceptors maintained lower resting [Ca2+]i than other retinal cells, and Ca2+ responses to 100 μM glutamate (Glu) and 80 mM KCl stimulation were smaller than those of cells in other retinal layers (Figure 1A, panels c and d). Retinal neurons in the INL and GCL responded to both pharmacological stimulations. Photoreceptors showed little or no increase in [Ca2+]i in the cell bodies (ONL) after 100 μM Glu stimulation (Figure 1A, panel c and d). However, response to Glu was detected in the synaptic layer (OPL in Figure 1A, panels c). Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels were expressed at birth in developing rod photoreceptors, were progressively upregulated until P21, and remained constant thereafter in mature photoreceptors (Figure 1A, panel e). In accordance with the expression of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, Ca2+ response to high-K+ stimulation was increased during retinal development (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Physiology of wild type adult photoreceptors.

(A) Calcium imaging of six week-old mouse retinal slices. (A-a) Slice preparation were loaded with Fura-2 and (A-b-d) stimulated with 100 μM glutamate (Glu) at 0:48 min and 80 mM KCl at 2:13 min. (A-b) Representative ratio images and (A-c) quantitation of [Ca2+]i in GCL, red; INL, orange, yellow, green; OPL, blue; ONL, purple. Resting [Ca2+]i and response to Glu stimulation were lower in the ONL compared to other layers. (A-d) Amplitude of Ca2+ response to Glu and KCl in the GCL (n = 9) and INL (n = 25) were compared with those in the ONL (n = 24). Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05. (A-e) Expression by microarray of voltage-dependent calcium channel subunits in isolated developing rod photoreceptors. (B) Patch clamp recording of rod photoreceptors in six week-old wild type retina. (B-a) DIC and Alexa594 fluorescence image of sliced retina showing the recorded cell. (B-b) Membrane voltage-clamp recording from −100 mV (red line) to 10 mV, with 10 mV increments. (B-c) Postnatal day (P)8 and adult retinal sections immunostained with anti-HCN-1 antibody. HCN-1 channel protein was expressed in the cell membrane of rod photoreceptors and in the INL at P8, and mostly localized to photoreceptor IS in the adult retina (white frame). (B-d) HCN-1 mRNA expression increased during postnatal retinal development. Data represent mean ± S.D of N = 3. *p < 0.05. (B-e) Expression by microarray of voltage-dependent potassium channel subunits in isolated developing rod photoreceptors. Scale bars, 50 μm in (A-a), 20 μm in (B-c). GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segment.

Membrane currents of rods were also measured in retinal slice culture preparations of 6 week-old mice (Figure 1B, panel a). In response to clamped membrane potential, mature rod photoreceptors showed rectifier-type outward current and hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih; red line in Figure 1B, panel b) mediated by HCN-1 channel activity. Expression of HCN-1 channel was detected in the cell membrane of developing photoreceptors and in the INL in the postnatal day (P)8 retina (Figure 1B, panel c) and was mostly localized to the photoreceptor inner segments (IS) in the adult retina (white frame in Figure 1B, panel c). HCN-1 channel subunits were upregulated during retinal development (Figure 1B, panel d). The rectifier-type outward current correlated with the expression of voltage-gated potassium channels, such as KCNB1 and KCNV2, in mature rod photoreceptors (Figure 1B, panel e). In accordance with the expression of voltage-gated potassium channels, membrane depolarization-induced outward current was increased during retinal development (Supplemental Figure 2). In addition, a large Ih was observed in P8 developing rods.

Developing Nrlp-eGFP-positive rods show smaller Ca2+ responses and membrane currents than other retinal cells upon membrane depolarization

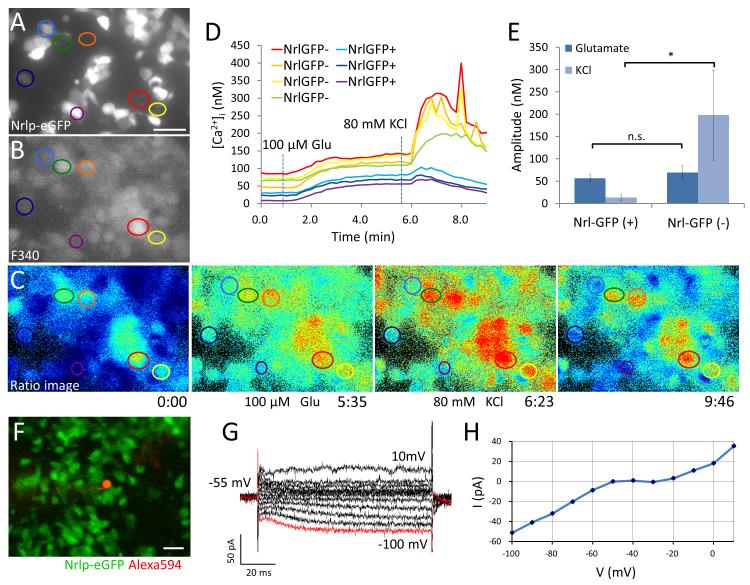

To test the neuronal function of developing rods in vitro, we performed intracellular Ca2+ imaging on dissociated retinal cells from Nrlp-eGFP mice. In these cell preparations, eGFP is specifically expressed in developing rods under the control of Nrl promoter. After dissociation of P3 mouse retina, cells were cultured on glass dishes for 5 days (cultures corresponding to approximately P8) to allow rod photoreceptor differentiation and Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells were tracked in the cultures (Figure 2A). Cultured retinal cells were stained with Fura-2 (Figure 2B). Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells (developing rods) maintained lower [Ca2+]i than Nrlp-eGFP-negative (all other) retinal cells in resting conditions (Figure 2C, D). Moreover, most cultured retinal cells responded to 100 μM Glu and 80 mM KCl stimulation (Supplemental Online Video 2), though Ca2+ responses to high-K+ stimulation in Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells were smaller than those in Nrlp-eGFP-negative cells (Figure 2D, E).

Figure 2. Cellular physiology of developing Nrlp-eGFP-positive rods.

(A) Nrlp-eGFP-positive (blue, dark blue, and purple) and –negative (red, orange, yellow, and green) cells dissociated from postnatal day (P)3 Nrlp-eGFP mouse retina were cultured for 5 days on glass-coated dishes (B) loaded with Fura-2, and (C-E) stimulated with 100 μM Glu (at 1:00 min) and 80 mM KCl (at 5:40 min). (C-D) Absolute [Ca2+]i was calculated from F340/F380 ratio images and plotted. (E) Average Ca2+ responses to Glu were comparable, whereas, Ca2+ responses to KCl in Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells (n = 7) were smaller than those in Nrlp-eGFP-negative cells (n = 8). (F-G) Membrane current in Nrlp-eGFP-positive developing rods was recorded by patch clamp technique from −100 mV (red line in G) to 10 mV, at 10 mV increments using Alexa594 (red) in the electrode solution for visualization (F). (H) I-V curve plotted from the data in (G) representing one single cell measurement. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05. Scale bars, 20 μm in (A) and (F).

The electrophysiological properties of Nrlp-eGFP-positive developing rods were further investigated by patch-clamp recording (Figure 2 F-H), which showed Ih (red line in Figure 2G) with small outward current. The I-V response curve (Figure 2H) illustrates the membrane hyperpolarization induced Ih in Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells.

Developing rods transplanted in the wild type mouse retina integrate into the ONL and show Ca2+ responses comparable to native rod photoreceptors

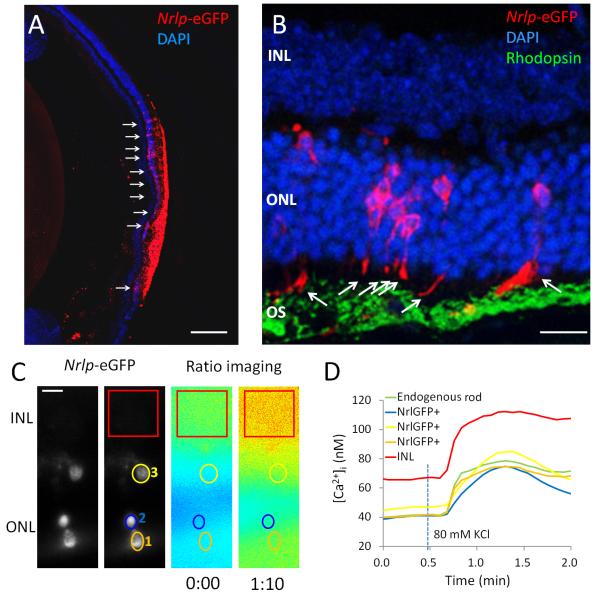

A suspension of cells dissociated from P5 Nrlp-eGFP mouse retina was injected into the sub-retinal space of wild type adult mice. Two weeks after transplantation, Nrlp-eGFP-positive donor cells were observed at the site of injection (Figure 3A). A subpopulation of transplanted Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells (7.8±4.6%; n=5) had integrated into the ONL (arrows). Some integrated cells showed photoreceptor-like morphology, including the appearance of structures resembling IS extending towards the outer segment (OS) region (Figure 3B). GFP did not localize to the OS.

Figure 3. Ca2+ responses of Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells grafted in adult wild type retina.

(A) Some Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells (red) transplanted in the sub-retinal space of wild type mouse, integrated in the ONL (arrows) and (B) showed IS-like structures (arrows). OS were stained with rhodopsin antibody (green) and nuclei with DAPI (blue). GFP does not localize to the OS. (C, D) Retinal slices were labeled with Fura-2 and [Ca2+]i was calculated from ratio images. Retinal cells in the INL (red) showed higher baseline level of [Ca2+]i than donor cells (orange, yellow, blue) or endogenous photoreceptors (green). Scale bars, 200 μm in (A); 20 μm in (B); 10 μm in (C). INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segment.

Next, we compared the increase in [Ca2+]i in grafted (Nrlp-eGFP-positive) cells and in native photoreceptors in the same retinal slice loaded with Fura-2. We stimulated the cells with high K+ to induce Ca2+ currents in the rod cell bodies. Glutamate stimulation would have resulted in increased Ca2+ in the rod axon terminals (Figure 1A, panel c). Nrlp-eGFP-positive grafted cells could be detected in the ONL and responded to high-K+ stimulation (Supplemental Online Video 3, Figure 3C). Retinal cells in the INL (red) showed higher baseline level of [Ca2+]i than donor cells (orange, yellow, and blue) or endogenous photoreceptors (green) (Figure 3D). The amplitude of Ca2+ response to high-K+ stimulation in Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells was comparable to that recorded in native (eGFP-negative) rod photoreceptors, and it was larger than that detected in developing rods before transplantation (see Figure 6H).

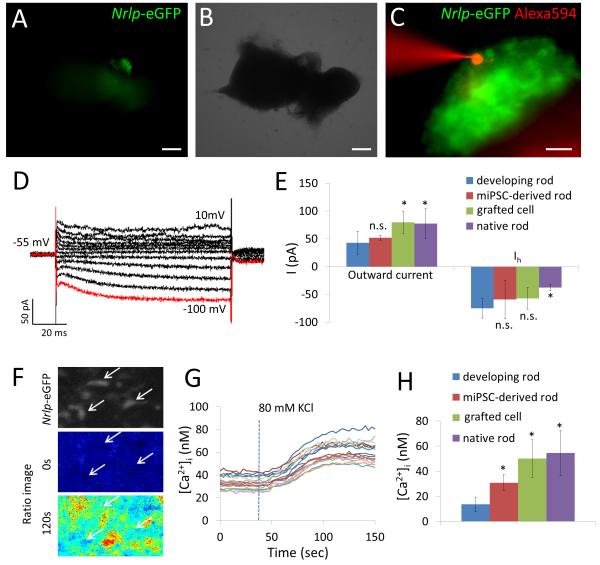

Figure 6. Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells show rod-like properties in vitro.

(A) Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells are visible in the differentiation culture. (B) Blight field image of the culture. (C) Patch clamp of mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells visualized with Alexa594 in the electrode solution. (D) Membrane current in Nrlp-eGFP-positive developing rods was recorded from −100 mV (red line) to 10 mV, at 10 mV increments. (E) Outward current and Ih in developing rods (P8) were compared with those in mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP positive cells, grafted cells or wild-type adult rods. (F) Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP positive cells were stained with Fura-2 and the Ca2+ imaging was performed. Arrows indicate Nrlp-eGFP positive cells. (G) Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP positive cells showed Ca2+ responses to high-K+ stimulation. (H) Ca2+ responses in developing rods (P8) were compared with those in mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP positive cells, grafted cells or wild-type adult rods. Scale bars, 200 μm (A, B); 20 μm (C). Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

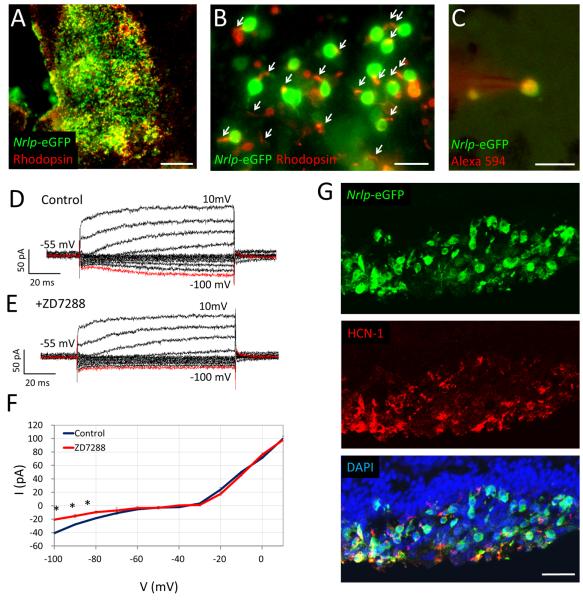

Transplanted rods develop OS-like protrusions and display photoreceptor-like membrane currents and Ca2+ responses in the degenerated retina

Dissociated Nrlp-eGFP mouse retinal cells were also transplanted in the subretinal space of degenerating six week-old Crx-knockout (KO) mouse retina, in which rod-like cells express little rhodopsin and fail to form OS 36. Two weeks after injection, surviving Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells were detected at the site of inoculation and expressed rhodopsin (Figure 4A). Furthermore, donor cells showed photoreceptor-like morphology and rhodopsin-positive OS-like protrusions (Figure 4B). Before recording, donor cells were identified by GFP in acute flat-mount retinal preparation (Figure 4C). Patch-clamp recording of grafted Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells revealed voltage-dependent rectifier outward current and Ih in response to membrane depolarization and hyperpolarization (Figure 4D). The voltage-dependent inward current recorded at membrane hyperpolarization was suppressed by treatment with ZD7288, an HCN channel blocker (Figure 4E). Specificity of ZD7288 suppression of Ih was also demonstrated by I-V response curve (−40.6 ± 8.5 pA: control; −20.8 ± 1.0 pA: ZD7288; 4 trials at −100mV; Figure 4F). Expression of HCN-1 channel in Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4G). Notably, outward current in the grafted cells and native photoreceptors was larger than that in developing rod cells, while Ih in developing rods and grafted cells was larger than that in wild type native rods (see Figure 6E). Furthermore, transplanted Nrlp-eGFP positive cells showed Ca2+ response to high-K+ stimulation (50.1 ± 15.1 nM; n=21; Supplemental Figure 3) comparable to that in adult wild-type rods (see Figure 6H).

Figure 4. Membrane properties of Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells grafted in Crx-KO mouse retina.

(A) Retinal flat mount image of developing Nrlp-eGFP-positive rods transplanted into the sub-retinal space of Crx-KO mice and expressing rhodopsin. (B) Some Nrlp-eGFP-positive donor cells extended rhodopsin-positive protrusions. (C) Patch clamp recording of membrane current in Nrlp-eGFP-positive donor cells identified by including Alexa594 in the electrode solution. (D, E) Membrane current in (D) control or (E) ZD7288-treated Nrlp-eGFP-positive donor cells recorded by membrane voltage-clamp from −100 mV (red line) to 10 mV, with 10 mV increments. (F) I-V curves were plotted using data from 4 trials before and after ZD7288 treatment. The voltage-dependent inward current recorded at membrane hyperpolarization was suppressed by treatment with ZD7288, an HCN channel blocker. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05. (G) The transplanted retinas were sectioned and stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-HCN-1 antibodies (red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm in (A), 20 μm in (B), (C) and (G).

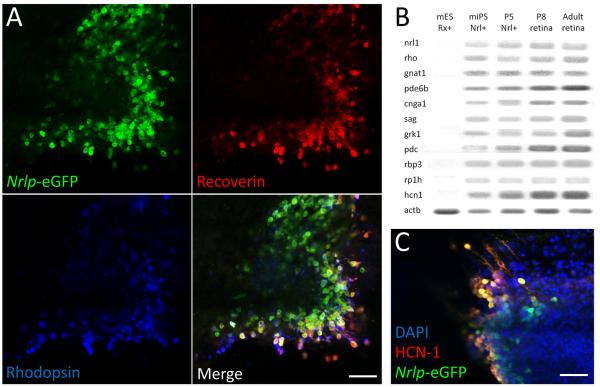

Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells exhibit physiological properties of developing rods

To evaluate whether rods derived from iPS cells display a bona fide photoreceptor phenotype, we compared rods derived from mouse iPS cells with native developing rods. Mouse iPS cells were reprogrammed from Nrlp-eGFP mouse fibroblasts and pluripotentiality was validated by formation of all three germ layers in immune-deficient mice (Supplemental Figure 4). After 25 days of differentiation, clusters of iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells were observed in the culture (Figure 5A). Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells in the clusters expressed rod photoreceptor markers recoverin and rhodopsin (Figure 5A). Similar to FACS-sorted Nrlp-eGFP cells from P5 mouse (P5 Nrl+) and whole retinas from P8 (P8 retina) and 6 week-old mouse (adult retina), FACS-sorted iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells (miPS Nrl+) expressed rod photoreceptor-specific mRNAs (Figure 5B), including those involved in phototransduction, (e.g., rhodopsin (rho), transducin-α (gnat1), phosphodiesterase-6β (pde6b), cyclic nucleotide gated channel-α1 (cnga1), arrestin (sag), rhodopsin kinase (grk1), phosducin (pdc), retinol binding protein (rbp3)), retinitis pigmentosa 1 homolog (rp1h), and HCN-1 channel (Figure 5B, C).

Figure 5. Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells express rod photoreceptor markers.

Mouse iPS cells generated from Nrlp-eGFP mouse fibroblasts were differentiated in vitro for 25 days to express Nrlp-eGFP. (A) Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells express rhodopsin and recoverin. (B) RT-PCR analysis for rod and phototransduction genes in mouse ES cell-derived Rx-GFP-positive cells (mES Rx+), mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells (miPS Nrl+), Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells from P5 mouse retina (P5 Nrl+), retinal tissue from P8 mouse (P8 retina), and retinal tissue from adult (6w) mouse. (C) Confocal images of iPS-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells expressing HCN-1 channel. Scale bars, 50 μm in (A) and (C).

Neither mouse ES cells nor GFP-positive cells from Rx-GFP knock-in mouse ES cell line (mES Rx+) 15, 40 that are at an early stage (day 10) of retinal differentiation in culture express photoreceptor-specific markers and HCN-1 (Figure 5B). Patch-clamp analysis (Figure 6 A-E) of iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells showed Ih in response to membrane hyperpolarization (red line in Figure 6D), which was suppressed by ZD7288 (Supplemental Figure 5). The membrane current from iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells was comparable to that of developing rods (outward current, 52.2 ± 4.4 pA; Ih, 59.2 ± 34.5 pA; n=3, Figure 6E). The iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP positive cells are stained with Fura-2 (Figure 6F). They showed Ca2+ responses to high-K+ stimulation (Figure 6G). The Ca2+ responses are larger than those in developing rods (Figure 6H), which may indicate that the rods have functionally maturated in vitro.

Discussion

Stem cell technology offers a considerable potential for biomedical research and therapy, allowing exploration of disease mechanisms, drug discovery, and cell replacement. ES and iPS cells can differentiate into several lineages, including neural cells 41, insulin-secreting islet-like cells 42, 43, hepatocytes 44, renal cells 45, cardiomyocytes 46, and hematopoietic cells 47. Mouse, monkey, and human ES/iPS cells have also been shown to differentiate into retinal neurons and RPE cells 14-17, 20-23. Recently, iPS cells from retinitis pigmentosa (RP) 18 and gyrate atrophy 19 patients were differentiated into rods and RPE and used to test the effects of drugs. Furthermore, transplantation of ES/iPS cell-derived RPE cells improved visual function in an RPE-deficient rat model of RP 48, 49. However, several retinal neurodegenerative diseases require replacement of photoreceptors, especially rods that are the first neurons to die in RP13, 50, 51 and age-related macular degeneration 52, 53. Assessment of transplantation outcome is based on survival, integration and functional differentiation of grafted cells. In this report, we describe parameters for the direct evaluation of photoreceptor function in retinal slice preparations. We recorded, for the first time, Ca2+ fluxes and membrane potentials from developing rod photoreceptors isolated from Nrlp-eGFP newborn mice or differentiated from Nrlp-eGFP iPS cells in vitro and in slice preparations after their transplantation in mouse models of retinal degeneration.

Nrlp-eGFP-positive rod photoreceptors maintained relatively lower baseline [Ca2+]i compared to other retinal neurons in dissociated cell cultures as well as in retinal slice preparations. This difference in baseline [Ca2+]i implies different Ca2+ homeostasis between rods and other neurons27. Our observation that Ca2+ responses to glutamate are transient in retinal slice preparation is consistent with previous studies in chicken54 and rat55. Ca2+ responses were not detected in the cell bodies of rods upon glutamate stimulation in wild type retina, as shown in Figure 1. Photoreceptor cells are packed tightly in the intact retina, thereby hindering access to glutamate, and/or Muller glia might buffer the exposure to glutamate. Therefore, only Ca2+ responses by a single high-K+ stimulation were compared in the transplanted photoreceptors. The increase in [Ca2+]i upon high-K+ stimulation is mostly observed in the cell body where photoreceptor L-type Ca2+ channels are localized26, 56.

Expression of HCN-1 channel increases during retinal development as rod photoreceptors mature. HCN-1 channels induce Ih in wild-type rods 57. Consistent with previous studies 32-34, 57, 58, we show that HCN-1 channels are localized in the IS of mature rod photoreceptors and that Ih in rods increases during early rod maturation as the expression of HCN-1 channel increases. Some HCN-1 positive cells in the INL are most likely rod bipolar cells or type-5 bipolar cells 34. In differentiation cultures, Nrlp-eGFP positive cells derived from mouse iPS cells expressed rod photoreceptor-specific genes as well as HCN-1 channels, and induced Ih, suggesting that iPS cell-derived cells have properties of developing rods and are amenable to retinal transplantation. Nonetheless, more efficient differentiation protocols are needed to obtain enough number of donor cells for retinal transplantation.

Comparison of Nrlp-eGFP donor cells before and after grafting and of native adult photoreceptors highlighted changes that occur in donor cell function upon transplantation and are suggestive of maturation. The amplitudes of the Ca2+ response and outward currents in grafted Nrlp-eGFP donor cells were larger compared to those of Nrlp-eGFP precursors in vitro and similar to those of native photoreceptors. In addition, Ih decreased after transplantation, yet remained larger than that in native rods, possibly indicating an intermediate maturation state in which HCN-1 channels are localized to the IS. In fact, HCN-1 channels and rhodopsin are localized to protrusions in grafted donor cells, consistent with a recent report 59. In Crx-KO mice, where OS and IS are missing, the expression level of HCN-1 is lower compared to that in wild type mice, indicating that HCN-1 expression is regulated by Crx. Taking into account the experimental age of the donor cells, functional maturation in the host retina is consistent with upregulation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel and potassium channel gene expression between birth and P28. The functionally immature state of donor rod cells may contribute to their better integration into the ONL11.

Ultimately, photoreceptor function is measured by their capacity to respond to light. That would have required infrared labeling, e.g., with IFP 60, eqFP650 61, and iRFP 62 rather than with a visible fluorescent protein (eGFP) to detect rods in the dark and without interference. Recently, light responses in grafted rods have been recorded with a suction electrode from OS 63. Since developing photoreceptors do not form OS in vitro, recording of light response in Nrlp-eGFP rod precursors and ES/iPS cell-derived rods in vitro could not be performed. Nonetheless, Ca2+ responses and membrane potential are a reliable measure of the photoreceptor capacity to perform sensory functions and the changes that we detected upon transplantation are suggestive of the acquisition of this capacity by maturing rod precursors.

In summary, we have investigated Ca2+ responses and electrophysiological properties of developing and grafted rods, and compared them to those of mature rod photoreceptors. We have established parameters that define photoreceptor function and showed that photoreceptors differentiated from transplanted developing rods display comparable currents to native rod photoreceptors and that iPS cell-derived rods have properties similar to developing rods. Our results suggest that grafted cells function as rod photoreceptors upon transplantation and further support the feasibility of cell-replacement therapy for retinal neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Calcium imaging of rods at different developmental stages in slice culture preparations.

(a) Postnatal day (P)5, (b) P8, and (c) adult retinas were sliced at 150 μm thickness. Retinal slices were stained with Fura-2 and stimulated with 80 mM KCl. (d) Increases in [Ca2+]i (nM) were calculated from each baseline. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

Supplemental Figure 2. Membrane current recording in rods at different developmental stages in slice culture preparations.

Membrane current in Nrlp-eGFP positive cells was recorded at postnatal day (P)5 or P8 (a). Recorded cells were identified by Alexa568 in the electrode solution. (c-f) Membrane current of Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells in (c) P5 and (d) P8 retina were recorded by membrane voltage-clamp from −100 mV to 20 mV, with 10 mV increments. From (c) and (d), I-V curves were plotted in (e) and (f), respectively. (b) Hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) at −100 mV and outward current at 10 mV in developing rods were compared with those in adult rods. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

Supplemental Figure 3. Calcium imaging of grafted rods in Crx-KO mouse retina.

(a) Nrlp-eGFP positive cell in flat-mounted Crx-KO mouse retina. Arrows indicate Nrlp-eGFP positive cell clusters. (b, c) Fura-2 ratio imaging of grafted cells in flat mounted Crx-KO mouse retina at 0 sec (b) and 120 sec (c). Red color indicates high concentration of intracellular Ca2+. (d) Nrlp-eGFP positive graft cells showed Ca2+ responses to high-K+ stimulation.

Supplemental Figure 4. Mouse iPS cells derived from Nrlp-eGFP mice differentiate into all three germ layers in the immunodeficient mice. (a) Colonies of Nrlp-eGFP mouse iPS cells. (b-d) Nrlp-eGFP mouse iPS cells were injected into the testis of immunodeficient (SCID) mice, and produced various types of tissues derived from three germ layers. Scale bars, 200 μm in (a), 100 μm in (b), (c), and (d).

Supplemental Figure 5. Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells show hyperpolarization-activated current.

Membrane current in (a) control or (b) ZD7288-treated iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells were recorded by membrane voltage-clamp from −100 mV (red line) to 10 mV, with 10 mV increments. (c) I-V curve was plotted from 4 trials. The voltage-dependent inward current recorded at membrane hyperpolarization was suppressed by treatment with ZD7288, an HCN channel blocker. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

Supplemental Online Video 1. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging of retinal cells in retinal slice preparation. Sliced retinas were stained with Fura-2. 100 μM glutamate (at 0:48 min) and 80 mM KCl (at 2:13 min) were added to the medium. Interval = 5.0 sec, 20 frames/sec, total time = 3.7 min (45 frames).

Supplemental Online Video 2. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging of Nrlp-eGFP-positive developing rods. Retinal cells from postnatal day (P)3 mice were cultured on glass-base dishes for 2-5 days. Retinal cells were stained with Fura-2. 100 μM glutamate (at 1:00 min) and 80 mM KCl (at 5:40 min) were added to the medium. Interval = 12.0 sec, 20 frames/sec, total time = 9.7 min (50 frames).

Supplemental Online Video 3. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging of donor cells in retinal slice preparation. Region of interest (ROI) #1-3 in the video correspond to the same ROI in Figure 3C and indicate donor cells in the wild type retina. 80 mM KCl (at 0:30 min) was added to the medium. Interval = 4.7 sec, 20 frames/sec, total time = 2.0 min (37 frames).

Acknowledgments

We thank Itaru Arai and Masao Tachibana (University of Tokyo) for help in patch clamp recording, Robert Farris (Biological Imaging Core, National Eye Institute) for Ca2+ imaging, Linn Gieser for Affymetrix Chip analysis, Juthaporn Assawachananont for retinal differentiation culture, Kyoko Iseki, Chie Ishigami, and Chikako Yamada for technical support, and lab colleagues for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Takahisa Furukawa (Osaka Bioscience Institute) for providing Crx-knockout mice.

Grants: This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, a grant-in-aid for Young Scientists (B) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (to KH), JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad (Kaitoku-NIH) (to KH), and by intramural research program of the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- 1.Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, et al. Treatment of leber congenital amaurosis due to RPE65 mutations by ocular subretinal injection of adeno-associated virus gene vector: short-term results of a phase I trial. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:979–990. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2240–2248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieving PA, Caruso RC, Tao W, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) for human retinal degeneration: phase I trial of CNTF delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3896–3901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otani A, Kinder K, Ewalt K, et al. Bone marrow-derived stem cells target retinal astrocytes and can promote or inhibit retinal angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2002;8:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/nm744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomita M, Adachi Y, Yamada H, et al. Bone marrow-derived stem cells can differentiate into retinal cells in injured rat retina. Stem Cells. 2002;20:279–283. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-4-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kicic A, Shen WY, Wilson AS, et al. Differentiation of marrow stromal cells into photoreceptors in the rat eye. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7742–7749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07742.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith LE. Bone marrow-derived stem cells preserve cone vision in retinitis pigmentosa. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:755–757. doi: 10.1172/JCI22930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, et al. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature. 2006;444:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature05161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akimoto M, Cheng H, Zhu D, et al. Targeting of GFP to newborn rods by Nrl promoter and temporal expression profiling of flow-sorted photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3890–3895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508214103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swaroop A, Kim D, Forrest D. Transcriptional regulation of photoreceptor development and homeostasis in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:563–576. doi: 10.1038/nrn2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda H, Osakada F, Watanabe K, et al. Generation of Rx+/Pax6+ neural retinal precursors from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11331–11336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500010102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osakada F, Ikeda H, Mandai M, et al. Toward the generation of rod and cone photoreceptors from mouse, monkey and human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:215–224. doi: 10.1038/nbt1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirami Y, Osakada F, Takahashi K, et al. Generation of retinal cells from mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;458:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamba DA, Karl MO, Ware CB, et al. Efficient generation of retinal progenitor cells from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12769–12774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601990103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin ZB, Okamoto S, Osakada F, et al. Modeling retinal degeneration using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer JS, Howden SE, Wallace KA, et al. Optic Vesicle-like Structures Derived from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Facilitate a Customized Approach to Retinal Disease Treatment. Stem Cells. 2011 doi: 10.1002/stem.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellough CB, Sernagor E, Moreno-Gimeno I, et al. Efficient stage-specific differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells toward retinal photoreceptor cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:673–686. doi: 10.1002/stem.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamba DA, Gust J, Reh TA. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived photoreceptors restores some visual function in crx-deficient mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamba DA, McUsic A, Hirata RK, et al. Generation, purification and transplantation of photoreceptors derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker BA, Park IH, Qi SD, et al. Transplantation of adult mouse iPS cell-derived photoreceptor precursors restores retinal structure and function in degenerative mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giannelli SG, Demontis GC, Pertile G, et al. Adult human Muller glia cells are a highly efficient source of rod photoreceptors. Stem Cells. 2011;29:344–356. doi: 10.1002/stem.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nachman-Clewner M, St Jules R, Townes-Anderson E. L-type calcium channels in the photoreceptor ribbon synapse: localization and role in plasticity. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steele EC, Jr., Chen X, Iuvone PM, et al. Imaging of Ca2+ dynamics within the presynaptic terminals of salamander rod photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4544–4553. doi: 10.1152/jn.01193.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheng Z, Choi SY, Dharia A, et al. Synaptic Ca2+ in darkness is lower in rods than cones, causing slower tonic release of vesicles. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5033–5042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5386-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demontis GC, Longoni B, Barcaro U, et al. Properties and functional roles of hyperpolarization-gated currents in guinea-pig retinal rods. J Physiol. 1999;515(Pt 3):813–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.813ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demontis GC, Moroni A, Gravante B, et al. Functional characterisation and subcellular localisation of HCN1 channels in rabbit retinal rod photoreceptors. J Physiol. 2002;542:89–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawai F, Horiguchi M, Suzuki H, et al. Na(+) action potentials in human photoreceptors. Neuron. 2001;30:451–458. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai F, Horiguchi M, Ichinose H, et al. Suppression by an h current of spontaneous Na+ action potentials in human cone and rod photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:390–397. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fyk-Kolodziej B, Pourcho RG. Differential distribution of hyperpolarization-activated and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in cone bipolar cells of the rat retina. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:891–903. doi: 10.1002/cne.21287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cangiano L, Gargini C, Della Santina L, et al. High-pass filtering of input signals by the Ih current in a non-spiking neuron, the retinal rod bipolar cell. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knop GC, Seeliger MW, Thiel F, et al. Light responses in the mouse retina are prolonged upon targeted deletion of the HCN1 channel gene. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:2221–2230. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrow AJ, Wu SM. Low-conductance HCN1 ion channels augment the frequency response of rod and cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5841–5853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furukawa T, Morrow EM, Li T, et al. Retinopathy and attenuated circadian entrainment in Crx-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1999;23:466–470. doi: 10.1038/70591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fusaki N, Ban H, Nishiyama A, et al. Efficient induction of transgene-free human pluripotent stem cells using a vector based on Sendai virus, an RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2009;85:348–362. doi: 10.2183/pjab.85.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eiraku M, Takata N, Ishibashi H, et al. Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;472:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, et al. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Assady S, Maor G, Amit M, et al. Insulin production by human embryonic stem cells. Diabetes. 2001;50:1691–1697. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rambhatla L, Chiu CP, Kundu P, et al. Generation of hepatocyte-like cells from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:1–11. doi: 10.3727/000000003783985179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batchelder CA, Lee CC, Matsell DG, et al. Renal ontogeny in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) and directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells towards kidney precursors. Differentiation. 2009;78:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kehat I, Kenyagin-Karsenti D, Snir M, et al. Human embryonic stem cells can differentiate into myocytes with structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:407–414. doi: 10.1172/JCI12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaufman DS, Hanson ET, Lewis RL, et al. Hematopoietic colony-forming cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10716–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191362598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haruta M, Sasai Y, Kawasaki H, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of pigment epithelial cells differentiated from primate embryonic stem cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1020–1025. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carr AJ, Vugler AA, Hikita ST, et al. Protective effects of human iPS-derived retinal pigment epithelium cell transplantation in the retinal dystrophic rat. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright AF, Chakarova CF, Abd El-Aziz MM, et al. Photoreceptor degeneration: genetic and mechanistic dissection of a complex trait. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrg2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, et al. Aging, age-related macular degeneration, and the response-to-retention of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:393–422. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curcio CA, Owsley C, Jackson GR. Spare the rods, save the cones in aging and age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2015–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson GR, Owsley C, Curcio CA. Photoreceptor degeneration and dysfunction in aging and age-related maculopathy. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:381–396. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sugioka M, Fukuda Y, Yamashita M. Development of glutamate-induced intracellular Ca2+ rise in the embryonic chick retina. J Neurobiol. 1998;34:113–125. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980205)34:2<113::aid-neu2>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinukawa J, Shimura M, Harata N, et al. Gliclazide attenuates the intracellular Ca2+ changes induced in vitro by ischemia in the retinal slices of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:789–798. doi: 10.1080/02713680591002808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baldridge WH, Kurennyi DE, Barnes S. Calcium-sensitive calcium influx in photoreceptor inner segments. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3012–3018. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Della Santina L, Piano I, Cangiano L, et al. Processing of retinal signals in normal and HCN deficient mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muller F, Scholten A, Ivanova E, et al. HCN channels are expressed differentially in retinal bipolar cells and concentrated at synaptic terminals. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2084–2096. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eberle D, Kurth T, Santos-Ferreira T, et al. Outer segment formation of transplanted photoreceptor precursor cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shu X, Royant A, Lin MZ, et al. Mammalian expression of infrared fluorescent proteins engineered from a bacterial phytochrome. Science. 2009;324:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1168683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shcherbo D, Shemiakina II, Ryabova AV, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2010;7:827–829. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Filonov GS, Piatkevich KD, Ting LM, et al. Bright and stable near-infrared fluorescent protein for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nbt.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pearson RA, Barber AC, Rizzi M, et al. Restoration of vision after transplantation of photoreceptors. Nature. 2012;485:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Calcium imaging of rods at different developmental stages in slice culture preparations.

(a) Postnatal day (P)5, (b) P8, and (c) adult retinas were sliced at 150 μm thickness. Retinal slices were stained with Fura-2 and stimulated with 80 mM KCl. (d) Increases in [Ca2+]i (nM) were calculated from each baseline. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

Supplemental Figure 2. Membrane current recording in rods at different developmental stages in slice culture preparations.

Membrane current in Nrlp-eGFP positive cells was recorded at postnatal day (P)5 or P8 (a). Recorded cells were identified by Alexa568 in the electrode solution. (c-f) Membrane current of Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells in (c) P5 and (d) P8 retina were recorded by membrane voltage-clamp from −100 mV to 20 mV, with 10 mV increments. From (c) and (d), I-V curves were plotted in (e) and (f), respectively. (b) Hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) at −100 mV and outward current at 10 mV in developing rods were compared with those in adult rods. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

Supplemental Figure 3. Calcium imaging of grafted rods in Crx-KO mouse retina.

(a) Nrlp-eGFP positive cell in flat-mounted Crx-KO mouse retina. Arrows indicate Nrlp-eGFP positive cell clusters. (b, c) Fura-2 ratio imaging of grafted cells in flat mounted Crx-KO mouse retina at 0 sec (b) and 120 sec (c). Red color indicates high concentration of intracellular Ca2+. (d) Nrlp-eGFP positive graft cells showed Ca2+ responses to high-K+ stimulation.

Supplemental Figure 4. Mouse iPS cells derived from Nrlp-eGFP mice differentiate into all three germ layers in the immunodeficient mice. (a) Colonies of Nrlp-eGFP mouse iPS cells. (b-d) Nrlp-eGFP mouse iPS cells were injected into the testis of immunodeficient (SCID) mice, and produced various types of tissues derived from three germ layers. Scale bars, 200 μm in (a), 100 μm in (b), (c), and (d).

Supplemental Figure 5. Mouse iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells show hyperpolarization-activated current.

Membrane current in (a) control or (b) ZD7288-treated iPS cell-derived Nrlp-eGFP-positive cells were recorded by membrane voltage-clamp from −100 mV (red line) to 10 mV, with 10 mV increments. (c) I-V curve was plotted from 4 trials. The voltage-dependent inward current recorded at membrane hyperpolarization was suppressed by treatment with ZD7288, an HCN channel blocker. Data represent mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05.

Supplemental Online Video 1. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging of retinal cells in retinal slice preparation. Sliced retinas were stained with Fura-2. 100 μM glutamate (at 0:48 min) and 80 mM KCl (at 2:13 min) were added to the medium. Interval = 5.0 sec, 20 frames/sec, total time = 3.7 min (45 frames).

Supplemental Online Video 2. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging of Nrlp-eGFP-positive developing rods. Retinal cells from postnatal day (P)3 mice were cultured on glass-base dishes for 2-5 days. Retinal cells were stained with Fura-2. 100 μM glutamate (at 1:00 min) and 80 mM KCl (at 5:40 min) were added to the medium. Interval = 12.0 sec, 20 frames/sec, total time = 9.7 min (50 frames).

Supplemental Online Video 3. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging of donor cells in retinal slice preparation. Region of interest (ROI) #1-3 in the video correspond to the same ROI in Figure 3C and indicate donor cells in the wild type retina. 80 mM KCl (at 0:30 min) was added to the medium. Interval = 4.7 sec, 20 frames/sec, total time = 2.0 min (37 frames).