Abstract

Background:

People with diabetes have a higher risk for myocardial infarction (MI) than do people without diabetes. It is extremely important that patients with MI seek medical care as soon as possible after symptom onset because the shorter the time from symptom onset to treatment, the better the prognosis.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to explore how people with diabetes experience the onset of MI and how they decide to seek care.

Methods:

We interviewed 15 patients with diabetes, 7 men and 8 women, seeking care for MI. They were interviewed 1 to 5 days after their admission to hospital. Five of the participants had had a previous MI; 5 were being treated with insulin; 5, with a combination of insulin and oral antidiabetic agents; and 5, with oral agents only. Data were analyzed according to grounded theory.

Results:

The core category that emerged, “becoming ready to act,” incorporated the related categories of perceiving symptoms, becoming aware of illness, feeling endangered, and acting on illness experience. Our results suggest that responses in each of the categories affect the care-seeking process and could be barriers or facilitators in timely care-seeking. Many participants did not see themselves as susceptible to MI and MI was not expressed as a complication of diabetes.

Conclusions:

Patients with diabetes engaged in a complex care-seeking process, including several delaying barriers, when they experienced symptoms of an MI. Education for patients with diabetes should include discussions about their increased risk of MI, the range of individual variation in symptoms and onset of MI, and the best course of action when possible symptoms of MI occur.

KEY WORDS: decision making, diabetes mellitus, experiences, grounded theory, myocardial infarction

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death among European adults with diabetes.1 Myocardial infarction (MI) is a life-threatening manifestation of coronary artery disease, and studies have shown that people with diabetes have higher risk for MI1,2 and higher long-term mortality after MI3 than do people without diabetes. It is extremely important that all patients with MI seek medical care as soon as possible after symptom onset because both mortality and morbidity are time dependent. The shorter the time from symptom onset to received treatment, the better the prognosis,4 and this applies to patients with and without diabetes.1

People with symptoms of MI often delay seeking medical care. Previous studies have shown that more than 50 % of MI patients wait at least 2 hours after symptom onset before arriving at hospital, and delay times have been constant over decades.5,6 Despite interventions to reduce prehospital delays, many people still delay the decision to seek medical care.7 Prehospital delay time is usually defined as time from symptom onset to arrival at hospital, and it can be divided into the patient decision phase and the transportation phase. The time it takes for the person to decide how to interpret and respond to symptoms is considered to be the main contributor to prehospital delay.8,9

The decision-making process from symptom onset to seeking medical care is complex and multifaceted.10,11 Decisions to seek medical care are influenced not only by knowledge about MI but also by experiences, beliefs, emotions, and contextual factors.12 Previous studies of prehospital experiences of MI have shown that chest pain is a commonly experienced symptom but that several other symptoms also occur and that they vary in onset, nature, and intensity.10,13,14 Symptoms also sometimes differ from patients’ expectations,10,13 and some patients do not interpret symptoms as cardiac in origin and deny their severity.15 Patients with diabetes may also be confused by the similarities of symptoms of MI to those associated with the glycemic fluctuations of diabetes.16,17 In a qualitative study of women with cardiac events, it was found that the presence of co-occurring chronic illness complicated symptom recognition and was related to extended delay in seeking care.18

Although several studies describe how patients interpret and respond to symptoms of MI,12–15,19–23 only 1 study, to our knowledge, describes the role of diabetes in that process. A qualitative study of women with diabetes and MI found that although some included diabetes in their story and checked their blood sugar levels when they experienced MI symptoms, other did not reflect upon diabetes in relation to their symptoms, nor did diabetes influence their decision making. Only a few of the women attributed their symptoms to diabetes.24

Whether patients with diabetes have different symptoms of MI from that of patients without diabetes has been researched, but with inconclusive results.25–29 Some studies have shown that patients with diabetes are more likely to have atypical symptoms of MI,25,26 whereas others found no such differences.28,29 Research using data from the Northern Sweden Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA) registry found that more patients with diabetes than without delayed seeking medical care for 2 hours or more,30 but there were no major differences between patients with and patients without diabetes in the presentation of symptoms of MI.31 To better understand how, when, and why people with diabetes seek care for symptoms of MI, it is important to define the process from the experience of the first symptoms to the act of seeking care. However, research in this area is limited. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore how people with diabetes experience the onset of MI and how they decide to seek care.

Methods

Design

A qualitative design based on grounded theory was used. Grounded theory is rooted in symbolic interactionism, which posits that reality is constructed and changed through interaction with others. In symbolic interactionism, interpretations and actions are processes that affect each other as people act in response to their interpretation of the situation. The method of grounded theory focuses on examining processes and actions with the objective of developing theory that is grounded in systematically collected and analyzed data.32–35

Setting

The participants were recruited from a coronary care unit at a university hospital in Sweden. After providing written and verbal consent, the patients were interviewed 1 to 5 days after the onset of their MI. The interviews, conducted by the first author in a private room within the coronary care unit, took place between September 2012 and October 2013.

Participants

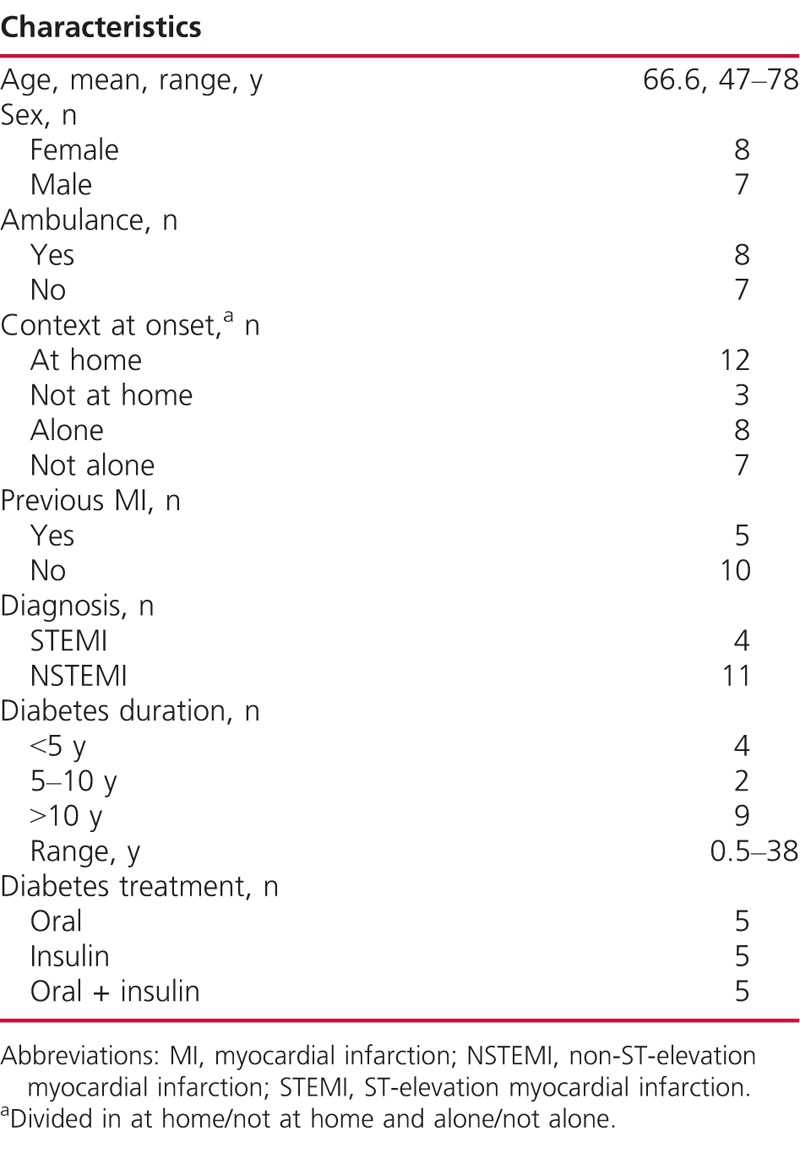

In a purposeful sample, 15 patients diagnosed with MI and diabetes participated in the study. The sampling aimed for variation in background characteristics among the participants. The group consisted of 7 men and 8 women aged 47 to 78 years (mean, 66.6 years) hospitalized with MI and with previously known diabetes. Characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Patients with serious complications or patients not able to participate in interviews because of communicative difficulties, confusion, or dementia were not included in the study.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Participants (n = 15)

Data Collection

The interviews followed a short interview guide and were informal and conversational in style. They contained the main question, “Can you please describe what happened when you became ill with MI?” Follow-up questions were asked to clarify and to encourage the participants to further develop the descriptions, especially about the feelings and thoughts they had during the onset. Questions were also asked about aspects that had facilitated or hindered their decision to seek medical care, as well as sociodemographics. Data collection and analysis continued in parallel until new interviews failed to contribute to any new interpretation, and saturation was reached after 15 interviews. Notes of preliminary interpretations or contextual information were made during or very soon after the interviews. The interviews were digitally recorded and lasted about 15 to 40 minutes.

Data Analysis

The analysis was conducted according to grounded theory.32–34 Each interview was transcribed verbatim soon after it was conducted, and the text was read several times and labeled with descriptive codes. This first level (open coding) used line-by-line or segment-by-segment coding. After open coding, selective coding was used to sort the open codes into clusters that were re-coded with a more specific focus. Questions such as “What is happening in the data?” and “What is expressed?” guided the analysis. The open and selective coding processes were facilitated by Open Code software (version 4.2).36 The selective codes were grouped together into categories whose properties and dimensions were further identified. Thereafter, a theoretic coding was performed to find links between categories and to identify a core category. Throughout the process, from the interviews through the analyses, notes and memos were written and figures were drawn. Those memos complemented the transcribed text and the figures captured and illuminated thoughts and ideas that emerged during the analysis to clarify the interrelationship of the categories. Constant comparisons were made between codes and between and within the categories, the emerging ideas, and the underlying text.

Methodological Rigor

Two of the authors performed the open and selective coding of the first 3 interviews together, and the first author performed the open and selective coding of the remaining interviews. The text and the codes were continually compared with the categories to ensure that the categories were not forced onto the data. The research team met regularly to discuss both the interviews and the emerging ideas until reaching a final agreement about the findings. In accordance with the grounded theory procedure settings, participants, data collection, and analysis are described in detail in the Methods section, the results include representative quotations from the participants.

Ethical Considerations

The participants were invited by the first author to participate in the study and gave their verbal and written informed consent. This study was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board, Umeå, Sweden (dnr 2012-306-32M), and it conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

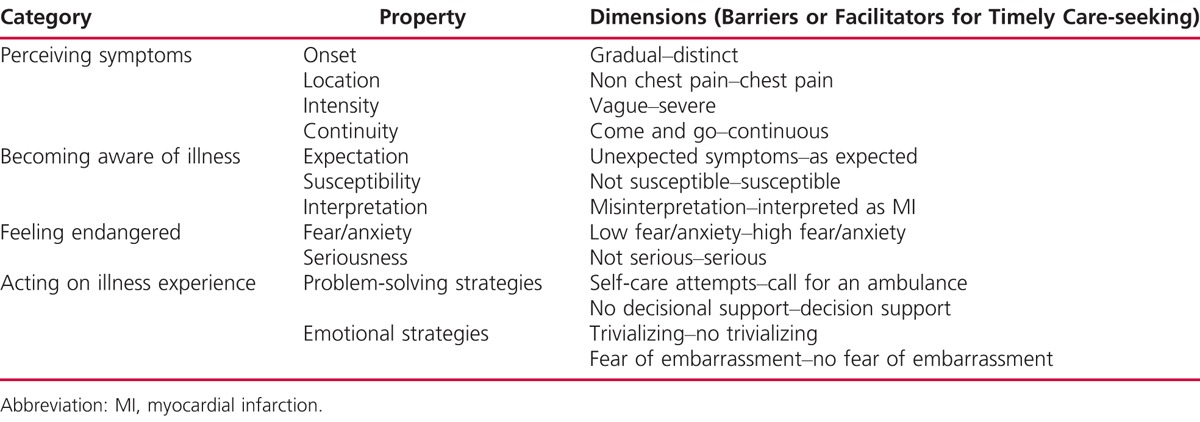

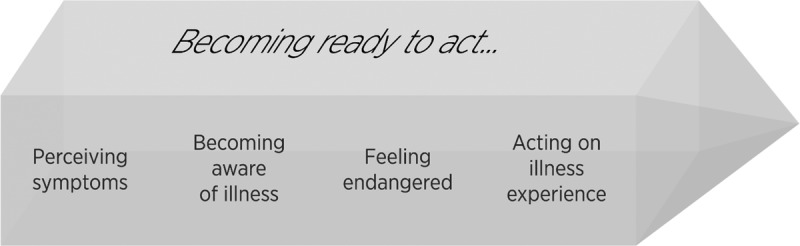

The analysis revealed the core category, “becoming ready to act,” which represents a process from perceiving the first symptoms of MI to making and acting upon the final decision to seek medical care. This process was complex and comprised 4 categories, labeled perceiving symptoms, becoming aware of illness, feeling endangered, and acting on illness experience. The core category and the categories provide a foundation for understanding the process of seeking care for MI among patients with diabetes (illustrated in the Figure). Table 2 presents a description of the properties and dimensions of the categories. The various dimensions of the properties could hinder or facilitate timely care-seeking.

TABLE 2.

Categories With Their Properties and Dimensions

FIGURE.

Model of becoming ready to act, a common process of care-seeking for myocardial infarction in people with diabetes.

Perceiving Symptoms

“Perceiving symptoms” included a range of symptom descriptions, with the following properties: onset, location, intensity, and continuity (Table 2). Symptom onset varied from a vague to a distinct and sudden onset. Some of the participants described symptoms that had gone on for days, weeks, and sometimes a month or more before the acute onset of MI. These symptoms (labeled in the literature as prodromal symptoms) were sometimes difficult to distinguish from the acute MI symptoms. They also contributed to delays in seeking care because the participants expected the symptoms to disappear, as they had on previous occasions. Many participants described not only pain located in the chest but also pain, discomfort, and numbness in other locations such as arms, back, stomach, jaws, and fingers. The participants described numerous other symptoms, such as shortness of breath, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, excessive sweating, diarrhea, and heart palpitations. Symptom intensity ranged from weak to severe and unbearable.

Well, it happened so fast, I could almost not keep up with it myself. It hurt so much and I could neither lie down nor sit. It blew out along my arm and chest. (i9)

The continuity of symptoms varied from those that came and went to those that continued and sometimes increased.

I had sensations of it, I felt pain in my arms. In both arms, and, yes, pain in the arms. I thought they felt heavy and, well…pain in the arms. Then it would get a bit better, but it came back…and so it went on for a while. (i1)

Symptoms other than chest pain, vague onset, and symptoms that came and went were all factors that complicated patients’ interpretation of their symptoms and awareness of their seriousness.

Becoming Aware of Illness

In “becoming aware of illness,” participants assessed and interpreted their symptoms as signs that something was wrong, which could be MI or some other illness they had. This category had 3 properties: expectation, susceptibility, and interpretation (Table 2).

Expectation concerned the participants’ ideas of what it would be like to experience MI. Some participants were unaware that MI could have symptoms other than typical chest pain, so the symptoms they experienced did not always signal to them the possibility of MI. The mismatch between the symptoms they experienced and their expectations of MI made them hesitate to seek care.

The symptoms that I had were not—I don’t think you would associate them with myocardial infarction. My arms felt somehow heavy. But I thought that [with myocardial infarction], one would be—have pain in—chest pain I think it should have been. (i1)

Almost none of the participants said they had received any information from their diabetes specialist nurses (DSN) or physicians about MI and its symptoms or how to respond to MI symptoms. Some participants had learned something about MI and its symptoms through books and television or recognized symptoms from the experiences of people they knew. Those with a previous MI recognized the symptoms and that contributed to their decision to seek care.

No, they [diabetes specialist nurses or doctors] have never talked about that [symptoms of myocardial infarction]. (i9)

Susceptibility concerned vulnerability and the participants’ expectation of their own risk of having an MI. Many participants had not thought themselves at risk for MI despite their diabetes. Some of those who had not thought themselves susceptible to MI said they had not received any information from healthcare professionals about diabetes as a risk factor for MI. It was described that MI was not seen as a complication of diabetes, and 1 participant thought that younger age protected him from MI.

I have never linked it [diabetes to risk of myocardial infarction], possibly because they [the healthcare personnel] never talked about it. (i5)

Susceptibility to MI was related to knowledge of risk factors for MI. It was also related to having had a previous MI or a family history of MI. Participants described it as being aware of the risk of MI, but not as anything they reflected upon or acted on in their daily life. The decision to seek medical care seemed to be delayed by not perceiving oneself as susceptible to MI.

Interpretation concerned the various ways participants interpreted their MI symptoms. Although all participants were diagnosed with diabetes, only 1 of them interpreted their first symptoms, cold sweat and heavy arms, as diabetes related. The others apparently had no thoughts that their symptoms might be caused by their diabetes.

Although some participants did immediately understand that their symptoms were caused by MI, others who did not understand that their symptoms were cardiac in origin misinterpreted them as signs of other conditions such as asthma, gastritis, disc herniation, or muscle strain.

I began to suspect it already on Sunday, and on Monday, it [pain] was a bit worse, but unconsciously when it disappears you do not think about it. And especially when you have asthma at the same time, then it is difficult. Is it the pulmonary tip up in the chest that hurts when I inhale cold air? It was colder than usual when I walked, so you become a bit pensive. Then when it eases, you think, it is the chest or the lungs instead of the heart. (i6)

Some also said they knew that something was wrong, but they did not know the cause.

Feeling Endangered

The category “feeling endangered” encompassed reactions to symptoms that were not relieved or that became more severe. This category had 2 properties: fear and/or anxiety and seriousness (Table 2).

Fear and/or anxiety concerned emotional and existential experiences that commonly increased when symptoms worsened. Some of the participants explicitly expressed strong fear and agony.

The feeling was that now I am going to die. Now I will get a new, more serious myocardial infarction, so now I am going to die. That was the first thing I thought about… It filled my mind. I thought about the children, I thought about everything. (i2)

Participants who had to wait for an ambulance experienced the wait as a further source of fear, whereas those who were quickly attended to felt safer by their proximity to the ambulance. Some participants expressed no experience of fear or anxiety, but they still considered that it was best to seek help and they felt more secure having done so. Absence of fear and anxiety may contribute to delay in seeking care.

If you had been frightened, you would have sought [medical care] sooner. And since I did not become frightened, I delayed it 1 day further… So, no, I never felt any fear. (i6)

Seriousness concerned how the participants got insights into the seriousness of their illness. Those with severe and bothersome symptoms described how they became aware of the seriousness of their illness and their need to seek immediate medical care. Even when symptoms were atypical and not attributed to the heart, strong and intense symptoms (eg, cold sweats) helped these participants to understand that their condition was serious. The participants reported that the feeling of seriousness contributed to their seeking care.

They were not such strong feelings, but I just thought that I had to seek medical care as fast as possible. Because it is tough, that’s what it is. You know, a heart rate of 150, that is quite high, so that is what you think about…I knew, knew what it was about. You try to save your own skin. (i3)

Acting on Illness Experience

The participants tried to manage their symptoms using different problem-solving and emotional strategies, sometimes in combination. Whereas some participants sought medical care fairly quickly, others tried other strategies first. When they eventually realized that their strategies were not working, they had to reconsider their first decision and try new strategies. This category comprises 2 properties: problem-solving strategies and emotional strategies (Table 2).

Problem-solving strategies included numerous self-care attempts to manage symptoms. They self-medicated with nitroglycerin or natural remedies for heartburn, rested, walked around to ease the pain, checked their blood pressure, or waited for the symptoms to wane. Only 1 participant measured blood glucose after the onset of symptoms.

I had pain and I took nitro, so it was a bit hard before I could have breakfast, and then I thought I should lie down on the couch. But I still had pain, so I took some more doses of nitro and lay down. I lay down for about 15 to 20 minutes, but it did not go away. (i10)

Some participants called for an ambulance almost immediately after the onset of symptoms, whereas others waited. Some called the primary healthcare center or healthcare information and were later referred to the hospital. This latter action was time-consuming and delayed participants’ contact with healthcare personnel. Those who were not alone at onset commonly described their symptoms to their companion(s), who then either contributed as a decision support or made the final decision to seek medical care and call for help. Some participants who were alone at onset contacted a relative who made sure that healthcare was sought, either by calling an ambulance or taking their ill relative to the emergency department.

Emotional strategies, sometimes combined with problem-solving strategies, included praying, trivializing symptoms, and attributing them symptoms to harmless causes and simply hoping that the symptoms would go away.

You feel that pain in the arms is just a trifle, or something like that. I thought that it would probably disappear… Well, seeking medical care, no, it was… I waited for a while to see if it would stop. But then, it became worse on Sunday and I thought that I maybe should check on it after all. (i1)

Other reasons for not seeking medical care immediately were reluctance to bother medical care services unnecessarily and fear of embarrassment if it were to turn out that they were not really ill. Participants who had previously sought medical care for similar symptoms and were told that the symptoms were not related to ischemic heart disease were hesitant to seek care.

Discussion

This study of how people with diabetes experience the onset of MI and how they decide to seek care shows that the process from first symptoms to decision making and finally acting to seek medical care is complex. Grounded theory analysis revealed the core category “becoming ready to act” and the related categories, perceiving symptoms, becoming aware of illness, feeling endangered, and acting on illness experience, to describe this process. Our findings suggest that the dimensions identified in the categories (Table 2) affect the care-seeking process and could be barriers or facilitators in timely care-seeking. Our study showed that most participants did not consider their diabetes when they experienced acute MI symptoms, nor did they reflect upon diabetes in their decision to seek medical care. Although people with diabetes are known to be at high risk for MI,1 many participants did not perceive themselves as susceptible to MI and MI was not described as a possible complication of their diabetes, as similar to other studies.37,38 Previous research on MI patients has also found that perceived risk of MI was a factor influencing the decision to seek medical care.12,21,39 In our study, we found that some participants had not talked about, nor received information about, MI or the risk of MI from their DSNs or physicians. A Swedish study of the DSN’s role in person-centered diabetes care showed that DSNs found it difficult to discuss the severity of diabetes and that they were worried about frightening their patients.40 Such a reluctance of DSNs to discuss the possibility of MI and other adverse outcomes may explain these patients’ unpreparedness for dealing with symptoms of MI.

Symptom perception varied between our participants, and symptoms that were not as expected for MI, such as those that had gradual onset, were vague, were not located in the chest, or came and went, seemed to be barriers to seeking timely care, which is congruent with previous research on patients with MI.10–13,20,24,39 Some participants in our study misinterpreted their first symptoms as not cardiac related, and only 1 interpreted these as related to diabetes, and this participant was the only 1 to test blood sugar after the onset of symptoms. Previous studies have shown that comorbid diseases, such as diabetes, were mentioned as reasons for interpreting MI symptoms as not cardiac related.17,39

Our findings also suggest that prodromal symptoms, defined as preinfarction angina and other cardiac-related symptoms that occur days or weeks before the acute MI event,41 could be a barrier to timely care-seeking. This conforms to previous studies of MI patients that describe prodromal symptoms15,20 and their possible role in delaying care-seeking.12,19 Participants in our study had sought medical care for heart-related symptoms but were sent home because no ischemic heart disease could be detected. One participant expressed feelings of not being taken seriously, which made him hesitate to seek medical care. Therefore, it is important always to take seriously the concerns of people who seek medical care for heart-related symptoms; if no ischemic heart disease can be detected, they should be instructed to seek medical care again if the symptoms come back or worsen.

Our findings demonstrate that the participants used both problem-solving and emotional strategies to manage their MI symptoms, as described previously in MI patients.13,15,19,20 Support from family or friends also seemed to be very important in the decision to seek care, and this is in line with previous studies.10–12,15,21,39 Therefore, it may be valuable to include significant others in the education of patients with diabetes, especially on how to handle the onset of acute symptoms.

Two recent grounded theory studies on decision making during MI, 1 Swedish study including men and a Turkish study including both men and women, found that symptoms varied and that intense symptoms and a feeling of threat or fear contributed to the decision to seek care, whereas difficulty interpreting the symptoms was a barrier to care-seeking. The participants in these studies also performed different self-care activities to manage the symptoms before care-seeking.42,43 Many of the findings in our study are similar with these results and with results from several other studies on care-seeking processes in MI patients.10–15,17–21 We can therefore assume that the process of care-seeking for MI in people with diabetes is similar to that for those without diabetes.

The process among participants with diabetes leading them to become ready to act should be interpreted as a model of care-seeking common to patients with diabetes (Figure). The process is dynamic because the various stages, the categories, in some cases can be difficult to distinguish and the process can go back and forth between stages, depending on how the symptoms are interpreted and what actions the patient takes. The direction in the model, however, is predetermined toward care-seeking. These findings are consistent with the Health Belief Model (HBM)44,45 and the Common Sense Model of self-regulation,46,47 theoretical models often used as frameworks for understanding care-seeking behavior in patients with MI. According to HBM, the decision to seek medical care is based on the perceived threat that the symptoms cause, and this, in turn, is dependent on perceived susceptibility and perceived severity of the disease. According to HBM, patients with diabetes who were informed about MI and their risk for it would likely seek medical care more quickly when MI symptoms occur. Other elements, according to HBM, that affect decision making are perceived benefits of and barriers to care-seeking, individual self-efficacy, and sociodemographic circumstances. Triggers or reminders to act are important, and symptoms could be such triggers.44,45 In the Common Sense Model, individuals are active problem solvers who make sense of a threat to their health through assessing their perceived symptoms and relating them to their individual knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. Action plans for coping with problems and emotions are formulated and initiated, and the individual appraises the success of the coping actions. If there is not enough progress in solving the problem, the coping plan will be reassessed and changed.46,47

Methodological Considerations

This study was qualitative in nature, with a sample size characteristic of qualitative methods, and is therefore not generalizable to a larger population of persons with diabetes and MI. The present study was retrospective, and data on participants’ prehospital experiences were collected 1 to 5 days after hospitalization. The short time between the onset of symptoms and the interviews reduces the risk of inaccuracy due to deterioration of memory. Some of the participants may have received analgesic or sedative drugs in the ambulance or during their first hours in hospital, and we do not know whether that affected their memory of the MI onset.

Clinical Implications

This study highlights the complexity of care-seeking for MI among patients with diabetes and identifies several barriers to their seeking care as quickly as necessary. Many patients with diabetes were found not to perceive themselves as susceptible to MI, and MI was not described as a complication of diabetes. It is therefore very important that patient education in diabetes include information about the risk for MI, the various symptoms that can signal MI, and recommended actions when such symptoms occur. Support from significant others such as family members and friends seemed to be important in the decision to seek care. It could be valuable to include significant others in patient education, especially in how to handle the onset of acute symptoms. The variety of symptoms and symptom onset between individuals is also important knowledge for healthcare personnel in emergency departments, primary care centers, and healthcare information centers.

What’s New and Important.

The care-seeking process in MI among patients with diabetes is complex, with many barriers to timely care-seeking.

People with diabetes often do not perceive themselves as susceptible to MI, and MI is not seen as a complication of diabetes.

Patient education in diabetes should include information about MI, and significant others should be invited to participate since they are important for the decision to seek care.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Umeå University, Sweden, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, the Swedish Diabetes Foundation, the County Councils of Västerbotten, and the Heart Foundation of Northern Sweden.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ryden L, Standl E, Bartnik M, et al. Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary. The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J. 2007; 28 (1): 88– 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004; 364 (9438): 937– 952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eliasson M, Jansson JH, Lundblad D, Näslund U. The disparity between long-term survival in patients with and without diabetes following a first myocardial infarction did not change between 1989 and 2006: an analysis of 6,776 patients in the Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Diabetologia. 2011; 54 (10): 2538– 2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boersma E, Maas AC, Deckers JW, Simoons ML. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet. 1996; 348 (9030): 771– 775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Isaksson RM, Holmgren L, Lundblad D, Brulin C, Eliasson M. Time trends in symptoms and prehospital delay time in women vs. men with myocardial infarction over a 15-year period. The Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 7 (2): 152– 158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saczynski JS, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, et al. Trends in prehospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction (from the Worcester Heart Attack Study). Am J Cardiol. 2008; 102 (12): 1589– 1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kainth A, Hewitt A, Sowden A, et al. Systematic review of interventions to reduce delay in patients with suspected heart attack. Emerg Med J. July 2004; 21 (4): 506– 508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ottesen MM, Dixen U, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L. Prehospital delay in acute coronary syndrome—an analysis of the components of delay. Int J Cardiol. 2004; 96 (1): 97– 103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gärtner C, Walz L, Bauernschmitt E, Ladwig KH. The causes of prehospital delay in myocardial infarction. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008; 105 (15): 286– 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Donnell S, Moser DK. Slow-onset myocardial infarction and its influence on help-seeking behaviors. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012; 27 (4): 334– 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nymark C, Mattiasson AC, Henriksson P, Kiessling A. The turning point: from self-regulative illness behaviour to care-seeking in patients with an acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18 (23): 3358– 3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pattenden JJ, Watt I, Lewin RJ, Stanford N. Decision making processes in people with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002; 324 (7344): 1006– 1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Isaksson RM, Brulin C, Eliasson M, Näslund U, Zingmark K. Prehospital experiences of older men with a first myocardial infarction: a qualitative analysis within the Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011; 25 (4): 787– 797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fors A, Dudas K, Ekman I. Life is lived forwards and understood backwards—experiences of being affected by acute coronary syndrome: a narrative analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014; 51 (3): 430– 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johansson I, Swahn E, Strömberg A. Manageability, vulnerability and interaction: a qualitative analysis of acute myocardial infarction patients’ conceptions of the event. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007; 6 (3): 184– 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stephen SA, Darney BG, Rosenfeld AG. Symptoms of acute coronary syndrome in women with diabetes: an integrative review of the literature. Heart Lung. 2008; 37 (3): 179– 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hwang SY, Jeong MH. Cognitive factors that influence delayed decision to seek treatment among older patients with acute myocardial infarction in Korea. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012; 11 (2): 154– 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruston A, Clayton J. Women’s interpretation of cardiac symptoms at the time of their cardiac event: the effect of co-occurring illness. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007; 6 (4): 321– 328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sjöström-Strand A, Fridlund B. Women’s descriptions of symptoms and delay reasons in seeking medical care at the time of a first myocardial infarction: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008; 45 (7): 1003– 1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Isaksson RM, Brulin C, Eliasson M, Näslund U, Zingmark K. Older women’s prehospital experiences of their first myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013; 28 (4): 360– 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brink E, Karlson BW, Hallberg LR-M. To be stricken with acute myocardial infarction: a grounded theory study of symptom perception and care-seeking behaviour. J Health Psychol. 2002; 7 (5): 533– 543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKinley S, Dracup K, Moser DK, et al. International comparison of factors associated with delay in presentation for AMI treatment. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004; 3 (3): 225– 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thuresson M, Jarlov MB, Lindahl B, Svensson L, Zedigh C, Herlitz J. Thoughts, actions, and factors associated with prehospital delay in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Heart Lung. 2007; 36 (6): 398– 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mayer DD, Rosenfeld A. Symptom interpretation in women with diabetes and myocardial infarction: a qualitative study. Diabetes Educ. 2006; 32 (6): 918– 924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA. 2000; 283 (24): 3223– 3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Culić V, Eterović D, Mirić D, Silić N. Symptom presentation of acute myocardial infarction: influence of sex, age, and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2002; 144 (6): 1012– 1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DeVon HA, Penckofer S, Larimer K. The association of diabetes and older age with the absence of chest pain during acute coronary syndromes. West J Nurs Res. 2008; 30 (1): 130– 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kentsch M, Rodemerk U, Gitt AK, et al. Angina intensity is not different in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. Z Kardiol. 2003; 92 (10): 817– 824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thuresson M, Jarlöv MB, Lindahl B, Svensson L, Zedigh C, Herlitz J. Symptoms and type of symptom onset in acute coronary syndrome in relation to ST elevation, sex, age, and a history of diabetes. Am Heart J. 2005; 150 (2): 234– 242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Angerud KH, Brulin C, Näslund U, Eliasson M. Longer pre-hospital delay in first myocardial infarction among patients with diabetes: an analysis of 4266 patients in the northern Sweden MONICA Study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013; 13: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Angerud KH, Brulin C, Naslund U, Eliasson M. Patients with diabetes are not more likely to have atypical symptoms when seeking care of a first myocardial infarction: an analysis of 4028 patients in the Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Diabet Med. 2012; 29 (7): e82– e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London, England: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Anna W. Qualitative Methodology for International Public Health. Umeå, Sweden: Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jeon YH. The application of grounded theory and symbolic interactionism. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004; 18 (3): 249– 256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. OpenCode 3.4. ICT Services and System Development and Division of Epidemiology and Global Health. OpenCode 4.0. 2013. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 2013. http://www.phmed.umu.se/english/divisions/epidemiology/research/open-code/?languageId=1. Accessed May 13, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carroll C, Naylor E, Marsden P, Dornan T. How do people with type 2 diabetes perceive and respond to cardiovascular risk? Diabetes Med. 2003; 20 (5): 355– 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martell-Claros N, Aranda P, Gonzalez-Albarran O, et al. Perception of health and understanding of cardiovascular risk among patients with recently diagnosed diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013; 20 (1): 21– 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. MacInnes JD. The illness perceptions of women following symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: a self-regulatory approach. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006; 5 (4): 280– 288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boström E, Isaksson U, Lundman B, Lehuluante A, Hörnsten A. Patient-centred care in type 2 diabetes - an altered professional role for diabetes specialist nurses [published online ahead of print October 25, 2013]. Scand J Caring Sci. doi:10.1111/scs.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hwang SY, Zerwic JJ, Jeong MH. Impact of prodromal symptoms on prehospital delay in patients with first-time acute myocardial infarction in Korea. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011; 26 (3): 194– 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nielsen S, Falk K, Gyberg A, Määttä S, Björck L. Experiences and actions during the decision making process among men with a first acute myocardial infarction [published online ahead of print April 23, 2014]. J Cardiovasc Nurs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yardimci T, Mert H. Turkish patients’ decision-making process in seeking treatment for myocardial infarction. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2014; 11 (2): 102– 111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974; 2 (4): 354– 386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984; 11 (1): 1– 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal E. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res. 1992; 16 (2): 143– 163. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leventhal H, Leventhal E, Contrada R. Self-regulation, health and behavior: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol Health. 1998; 13: 717– 733. [Google Scholar]