Summary

TP508, a 23-amino acid RGD-containing synthetic peptide representing residues 508 to 530 of human prothrombin, mitigates the effects of endothelial dysfunction in ischaemic reperfusion injury. The objective of this study was to investigate whether TP508 binds to members of the integrin family of transmembrane receptors leading to nitric oxide synthesis. Immobilised TP508 supported adhesion of endothelial cells and αvβ3-expressing human embryonic kidney cells in a dose- and RGD-dependent manner. Soluble TP508 also inhibited cell adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen. The involvement of αvβ3 was verified with function-blocking antibodies and surface plasmon resonance studies. Adhesion of the cells to immobilised TP508 resulted in an induction of phosphorylated FAK and ERK1/2. In endothelial cells, TP508 treatment resulted in an induction of nitric oxide that could be inhibited by LM609, an αvβ3-specific, function-blocking monoclonal antibody. Finally, TP508 treatment of isolated rat aorta segments enhanced carbachol-induced vasorelaxation. These results suggest that TP508 elicits a potentially therapeutic effect through an RGD-dependent interaction with integrin αvβ3.

Keywords: TP508, eNOS, nitric oxide, endothelial dysfunction, integrin

Introduction

Vascular endothelial dysfunction (VED) is characterised by reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator (1). NO bioavailability is reduced either by decreased production or increased removal of NO. Factors influencing decreased production of NO include reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), failure to activate eNOS and a lack of substrate or eNOS cofactors (2). Reduced vasodilation results in impaired blood flow and response to angiogenic factors that could lead to atherosclerosis, plaque formation and cardiovascular pathology (3). VED is associated with several pathological conditions, including hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, atherosclerosis, stroke, diabetes mellitus and congestive heart failure (4–9). Consequently, disturbed endothelial function is of clinical significance. Proposed pharmaceutical treatments for VED exist, including L-arginine, I-methylnicotinamide, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors and endothelin receptor antagonists, but many have been approved only for specific indications related to VED such as hypertension and erectile dysfunction (10).

TP508, a 23-amino acid synthetic peptide representing residues 508 to 530 of human prothrombin, elicits a variety of potential therapeutic effects in a NO-dependent manner. A previous study has shown that TP508 exhibited reversal of VED in porcine ischaemic hearts and human endothelial cells via an upregulation of endothelial NO synthesis (11). Recent studies using normal and hypercholesteraemic pig models show that TP508 treatment results in a significant reduction in infarct size as well as elevated levels of phosphorylated eNOS (peNOS) compared to untreated pigs (12, 13). These studies using isolated coronary arterioles from ischaemic regions show that TP508 significantly enhances vascular dilation in an endothelium-dependent manner (11–13). These results provide evidence supporting eNOS phosphorylation and endothelium-dependent coronary microvascular relaxation by TP508.

The effects of TP508 are well documented, but its mechanism of action has not yet been completely elaborated. TP508 was initially selected for its ability to compete with the binding of thrombin to its receptors on fibroblasts (14). However, it lacks the protease domain of thrombin and is unlikely to activate intracellular signalling through protease-activated receptors (PARs) in a manner similar to that observed for thrombin. Interestingly, the region of thrombin that corresponds to TP508 contains an RGD sequence that is buried within the structure of native thrombin and may only be exposed when thrombin is proteolytically cleaved or its structure is altered by high salts or immobilisation onto charged surfaces (15, 16). Thrombin has previously been shown to support endothelial cell adhesion in an RGD-dependent manner when immobilised to a surface (15–17). This interaction was determined to be mediated primarily through integrins αvβ3 and α5β1 (16, 18–19). Other studies have provided evidence that some thrombin-induced signalling events are mediated through αvβ3 specifically (20–21).

Our working hypothesis is that TP508 mitigates VED by inducing NO via the integrin αvβ3. Due to the presence of an RGD sequence in TP508, integrins that specifically recognise this motif, including αvβ3 and α5β1, were targeted as potential receptors. The involvement of integrins was investigated by determining the ability of endothelial cells and cells over-expressing selective integrins to adhere to immobilised TP508 and the ability of soluble TP508 to compete for the natural ligands fibrinogen or fibronectin. Additionally, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies were performed to measure the direct interaction of TP508 and αvβ3. Integrin-mediated signalling, NO production and vasorelaxation were also studied. The role of this interaction in NO induction was determined by using inhibitors of integrin function to block TP508-mediated NO induction. Results from this study indicate that TP508 induction of NO synthesis in endothelial cells is mediated by integrin αvβ3.

Materials and methods

Cells, peptides and antibodies

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from Lonza (Boston, MA, USA). All experiments using HUVEC were performed at passages 2 to 4. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). The αvβ3-expressing HEK 293 cells (HEK-αvβ3 were constructed as previously described (22), using full-length β3 cDNA provided by Dr. T. O’Toole (Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, OH, USA). Cells were grown in T-75 culture flasks at 37°C, 5% CO2 in 10 ml of complete EGM-2MV media (HUVEC), DMEM + 10% FBS (HEK) or DMEM + 10% FBS containing 200 μg/ml Hygromycin and 400 μg/ml Neomycin (HEK-αvβ3). TP508 (AGYKPDEGKRDACEGDSGGPFV), scrambled TP508 (scrTP508) (KAPSEVDKAGDRDGYGFCGGPGE) and RAD-TP508 (AGYKPDEGKRADACEGDSGGPFV) were synthesised by American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). GRGDSP peptide was purchased from Anaspec (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-β3, FAK, ERK1/2 (cat #4696) and pERK1/2 (cat #4377) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-pFAK, LM609 (αvβ3) and MAB1969 (α5β1) were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). A23187 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Human fibrinogen, fibronectin and α-thrombin were purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN, USA).

Adhesion assay

Adhesion assays were performed as previously described (23). Briefly, wells of a 96-well plate were coated with 1 μg/ml fibrinogen or fibronectin or indicated concentrations of TP508, scrTP508 or RAD-TP508 in PBS and incubated at 37°C for 3 hours (h). The plate was blocked with 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h at 23°C. HEK-αvβ3 or HUVEC (passage 2 to 4) were labelled with 10 μM calcein AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 minutes (min) at 37°C and suspended to a final concentration of 5 × 105 cells/ml in phenol red-free, serum-free media containing 0.2% BSA. If required, the cells were incubated in the presence of 10 μg/ml function-blocking antibody or indicated concentration of peptide for 15 min prior to plating. The cells were allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. The plates were washed gently, and the fluorescence measured (Ex485/Em530) with a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Baseline was determined by measuring fluorescence obtained when labelled cells were adhered to uncoated and blocked wells.

Adhesion-induced FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation

Assays for FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were performed as previously described (24). Briefly, 100 mm petri dishes were coated with 10 ml of 400 μg/ml TP508, scrTP508 or 2 μg/ml fibrinogen in PBS and incubated uncovered at 23°C in a laminar flow hood until the saline completely evaporated. Dishes were blocked with 2% BSA for 1 h at 37°C. As a control, dishes were coated with poly-D-lysine at 100 μg/ml. HEK-αvβ3 cells were suspended in phenol red-free DMEM containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at a concentration of 6 × 106 cells/ml. Then, 5 ml of the cell suspension was added to each plate and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Additionally, a 5 ml aliquot of cells was maintained in suspension for 1 h. Following the incubation, cells were lysed and the lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for detection of total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 and FAK.

Nitric oxide assay

Nitric oxide assays were performed as previously described (25). Briefly, HUVEC at 90% confluence were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in KRH buffer (129 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaHCO3, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.8 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, pH7.4) and then treated with A23187 or TP508 at a final concentration of 20 μM or 150 μg/ml, respectively, in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml LM609. An equivalent volume of KRH buffer was added to untreated cells (NT). A total of 50 μl of sample collected from each well at 1 h and carefully injected into purge chamber of Sievers Nitric oxide analyzer NOA 280i (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) for nitric oxide analysis. NO concentrations were calculated for the samples using a standard curve obtained by injecting dilutions of sodium nitrite.

Muscle-bath assay

Muscle-bath assays were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, rat aortic rings (2 mm) with intact endothelium were harvested from eight-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats. Rings were mounted on an eight-chamber muscle bath (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA, USA) and equilibrated in KREBS-bicarbonate buffer at 37°C for 1 h. Force measurements were obtained using force transducers (Panlab, Barcelona, Spain) interfaced with Powerlab data acquisition system and Chart software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Rings were treated twice with 70 mM KCl-Krebs to determine the maximal contractile force and then washed with KREBS-bicarbonate buffer. Duplicate rings were treated with 0 or 2.3 mg/ml (1 mM) TP508 for 1 h, followed by treatment with 500 nM norepinephrine for 10 min, then increasing doses of carbachol (0, 1, 10, 100, 500, 750, 1,000, 5,000 nM). All rings were then washed and treated with 70 mM KCl-KREBS to verify ring viability.

Surface plasmon resonance studies

Binding parameters for the interaction of TP508 with integrin αvβ3 were measured by using a BIAcore 2000 (GE Healthcare). CM5 chip was coated with 10 mg/ml of TP508 peptide or RAD-TP508 peptide using a thiol coupling method according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Different concentrations of human integrin −αvβ3 (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), ranging from 0.053 to 1.06 μM in HBS-P buffer supplemented with 1 mM MnCl2, were flowed over cells containing −1,300 RU TP508 or −1,290 RU RAD-TP508. Each association/dissociation cycle was followed by injection of regeneration buffer containing 2 M NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. All data were corrected for the response obtained using a blank reference flow cell that was activated using the reagents for thiol coupling procedure and then blocked with ethanolamine. Binding data were analysed using the BIAevaluation software module (v 4.1). The association rate constant (ka) and the dissociation rate constant (kd) were obtained by global analysis of the association-dissociation curves after obtaining the best fit to the interaction model.

Statistics

Data were reported as means ± standard error (SE). Differences between treatments were analysed using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks. Multiple comparisons vs. control group were tested using Dunn's method with a family-wise error rate of 0.05. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Immobilised TP508 promotes cell adhesion and is RGD-dependent

The presence of an RGD motif within the TP508 sequence led to testing the ability of the peptide to support cell adhesion. Previous studies have demonstrated that integrins αvβ3 and α5β1 bind to RGD-containing ligands. Therefore, the ability of TP508 to bind to these integrins was initially tested in HEK 293 cells, an immortalised cell line. As shown in ▶Figure 1A, HEK 293 cells did not exhibit significant adhesion to immobilised TP508 or fibrinogen, but did exhibit adhesion to immobilised fibronectin. It is well established that HEK 293 cells do not express the integrin β3 subunit, but do express OC5P1 (27). Expression of α5β1 on HEK 293 cells was confirmed by both flow cytometry and Western blot analysis (data not shown). To identify the specific integrin involved in adhesion to TP508, the ability of HEK 293 cells stably-expressing integrin αvβ3 (HEK-αvβ3) to adhere to immobilised TP508 was tested (Fig. 1B). Expression of αvβ3 was verified by flow cytometry and Western blot analysis (data not shown). Adhesion of HER-αvβ3 to immobilised TP508 was concentration-dependent with maximal adhesion being observed at 300 and 900 μg/ml TP508. Adhesion was RGD-dependent as RAD-TP508 (peptide containing a G→A mutation) and scrTP508 (scrambled TP508 peptide) did not support HEK-αvβ3 adhesion. In order to investigate the role of TP508 in VED, the ability of endothelial cells to adhere to TP508 was tested. HUVEC cells were used for the experiments and expression of α5β1 and αvβ3 was verified by flow cytometry and Western blot analysis (data not shown). Similar to that observed with HEK-αvβ3, HUVEC adhesion to TP508 was concentration-dependent (Fig. 1C). Additionally, adhesion was RGD-dependent as RAD-TP508 and scrTP508 did not support HUVEC adhesion. These results show that immobilised TP508 is capable of supporting cell adhesion.

Figure 1. Adhesion to TP508 is RGD-dependent.

A) HEK cells do not adhere to immobilised TP508. B) Adhesion of HEK-αvβ3 cells to TP508 is RGD-dependent. C) Adhesion of HUVEC to TP508 is RGD-dependent. TP508, fibronectin (FN) or FGN were coated on the surface of an Immulon 4BHX plate, and an adhesion assay was performed as described in Materials and methods. Results are expressed as fluorescence of adherent cells determined by reading with a Spectramax M2 plate reader. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and statistical significance is determined by Kruskal-Wallis test, n=3, (*p<0.05).

Adhesion to TP508 is mediated through integrin αvβ3

To clarify the involvement of αvβ3 in adhesion to immobilised TP508, the ability of specific integrin function-blocking antibodies to inhibit adhesion to immobilised TP508 was determined. Addition of αvβ3-specific function-blocking mAb, LM609, inhibited HEK-αvβ3 adhesion to immobilised TP508, at all concentrations of TP508 (▶Fig. 2A). In contrast, the α5β1-specific function-blocking mAb, MAB1969, did not inhibit HEK-αvβ3 adhesion to immobilised TP508. Similarly, adhesion of HUVEC to immobilised TP508 was inhibited by LM609 at all concentrations of TP508 (Fig. 2B). The α5β1-specific function-blocking mAb, MAB1969, had no effect on HUVEC adhesion to immobilised TP508. These results confirm that adhesion to immobilised TP508 is mediated through αvβ3.

Figure 2. Integrin αvβ3 mediates adhesion to TP508.

A) Adhesion of HEK-αvβ3 cells to immobilised TP508 is mediated through integrin αvβ3. B) Adhesion of HUVEC to immobilised TP508 is mediated through integrin αvβ3. An Immulon 4HBX plate was coated with the indicated concentrations of TP508 as described in Materials and methods. Calcein-labelled HEK-\g=a\v\g=b\3 cells (A) or calcein-labelled HUVEC (B) were allowed to adhere to coated wells for 30 min at 37°C in the presence of 1 μM anti-α5β1, function-blocking mAb (MAB1969), anti-αvβ3 function-blocking mAb (LM609) or in the absence of any function-blocking antibody (No mAb). Following 30 min incubation, plates were washed and fluorescence was determined by reading with a Spectramax M2 plate reader. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and statistical significance is determined by Kruskal-Wallis test, n=3, (*p<0.05).

Soluble TP508 interacts with integrin αvβ3 in an RGD-dependent manner

The cell adhesion data described above indicated that immobilised TP508 interacted specifically with αvβ3 in an RGD-dependent manner. To more closely mimic physiological conditions in which TP508 is not immobilised onto a surface, the ability of soluble TP508 to inhibit cell adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen was determined. Cells were allowed to adhere to immobilised fibrinogen for 30 min in the presence of varying concentrations of soluble TP508, RAD-TP508, scrTP508 or GRGDSP peptide, after which cell adhesion was determined. Soluble TP508 inhibited adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen in a dose-dependent manner with maximal inhibition occurring at 900 μg/ml TP508 (▶Fig. 3A). The observed effect was RGD-dependent as RAD-TP508 did not influence cell adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen. As a control, GRGDSP peptide effectively inhibited cell adhesion. Similar to that observed with HEK-αvβ3, soluble TP508 inhibited adhesion of HUVEC to immobilised fibrinogen in a dose-dependent manner with maximal inhibition of adhesion being observed at 300 and 900 μg/ml TP508 (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the observed inhibition was RGD-dependent as RAD-TP508 and scrTP508 did not affect HUVEC adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen. These results verify that soluble TP508 interacts specifically with αvβ3 and that this interaction is RGD-dependent.

Figure 3. Inhibition of adhesion by soluble TP508.

A) Soluble TP508 inhibits HEK-αvβ3 cell adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen. B) Soluble TP508 inhibits HUVEC adhesion to immobilised fibrinogen. Cells were allowed to adhere to fibrinogen-coated wells for 30 min in the presence of the indicated concentration of TP508, scrTP508, RAD-TP508 or GRGDSP. Following 30 min incubation, plates were washed and fluorescence was determined by reading with a Spectramax M2 plate reader. Results are expressed as percentage of adhesion to fibrinogen. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and statistical significance is determined by Kruskal-Wallis test, n=3, (*p<0.05).

TP508 interacts with αvβ3 with a KD of 13.8 ± 0.9 nM

To characterise the TPSOS-αvβ3 interactions further, the dissociation constant of the binding of TP508 to isolated integrin αvβ3 was determined using SPR. TP508 or RAD-TP508 were coupled to the chip, and the SPR profiles were examined across a range of αvβ3 concentrations. ▶Figure 4 shows the sensograms for the binding of selected αvβ3 concentrations to TP508. The association and dissociation phases were fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. The KD calculated from these analyses using six distinct concentrations of αvβ3 (0.053–1.06pM) was 13.8 ± 0.9 nM. No binding to RAD-TP508 was observed.

Figure 4. Surface plasmon resonance analysis of the TP508-αvβ3 interaction.

The chip surface was coated with TP508 or RAD-TP508, and then purified integrin αvβ3 was flowed over the chip at varying concentrations. An overlay of sensor-grams for the binding of selected concentrations of αvβ3 to TP508 is shown. The association and dissociation phases were fitted and linearised according to the BIAevaluation software (version 3.1). The KD calculated from six distinct concentrations (from .053 to 1.06μM) was 13.8 ± 0.9 nM. No binding to RAD-TP508 was observed.

Adhesion to immobilised TP508 results in induction of FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation

Integrin-mediated cell adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins leads to stimulation of intracellular events including phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and mitogen activated protein kinase (ERK1/2), resulting in cytoskeletal rearrangements (28). To examine whether association between TP508 and αvβ3 resulted in phosphorylation of FAK and ERK1/2, the phosphorylation state of FAK and ERK1/2 upon adhesion of HEK-αvβ3 cells to TP508 was tested by Western blot analysis. Adhesion of HEK-αvβ3 cells to immobilised TP508 resulted in a 2.4-fold induction of pFAK as compared to cells adhered to poly-D-lysine (▶Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained with cells adherent to immobilised fibrinogen. Likewise, cells adherent to immobilised TP508 and fibrinogen exhibited an approximately two-fold induction of pERK1/2 as compared to cells adhered to poly-D-lysine. As expected, treatment of lysates from cells adherent to fibrinogen with alkaline phosphatase resulted in less pFAK and pERK1/2 than that observed on poly-D-Lysine. Thus, integrin-mediated adhesion to immobilised TP508 initiates intracellular signalling.

Figure 5. Adhesion to TP508 induces phosphorylation of FAK and ERK1/2.

A) Adhesion to immobilised TP508 results in an induction of phosphorylated FAK. B) Adhesion to immobilised TP508 results in an induction of phosphorylated ERK1/2. HEK-αvβ3 cells were adhered to plates coated with fibrinogen (FGN) or TP508 as described in Materials and methods. As a negative control, lysate was obtained from HEK-αvβ3 cells plated on a poly-D-Lysine-coated plate. Lysates from cell adherent to fibrinogen were also treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at 37°C. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were probed with anti-pERK1/2, anti-total ERK1/2, anti-pFAK, anti-total FAK and anti-GAPDH antibodies. Band intensities were quantified and normalised to GAPDH. After normalisation, the ratio of phosphorylated to total was determined. Results are expressed as phosphorylated/total ratio. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and statistical significance is determined by Kruskal-Wallis test, n=3, (*p<0.05).

TP508 induces NO synthesis in HUVEC

TP508 has been shown to induce numerous biological effects in a variety of cell lines including the induction of NO in endothelial cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (29). However, the role of integrins, if any, in this observed biological effect has not yet been determined. To examine the effect of TP508 on production of NO in endothelial cells, media from TP508-treated cells was injected into an NO analyser. TP508 treatment of HUVEC resulted in an approximate 1.6-fold induction of NO compared to untreated samples (▶Fig. 6). TP508 induction of NO in HUVEC was statistically indistinguishable from that of A23187, a potent inducer of NO (p>0.05). TP508 treatment had no effect on NO production in suspended HUVEC’s (data not shown). The involvement of integrins was determined by the use of LM609, an αvβ3-specific inhibitory antibody. Treatment of cells with TP508 in the presence of LM609 resulted in a dramatically reduced NO production as compared to TP508-treatment alone. The amount of NO produced in the presence of LM609 was very similar to that observed in untreated cells (p>0.05). Treatment of HUVEC with LM609 alone had no effect on overall levels of NO produced (data not shown). Treatment of cells with TP508 or LM609 did not result in any cell detachment. The phosphorylation of eNOS on TP508 treatment of HUVEC was also tested, and the results agreed with that observed in NO production. An approximate 1.5-fold induction of peNOS was observed in HUVEC cells treated with TP508 as compared to untreated (p=0.08). Thus, the induction of NO by TP508 maybe mediated through integrins.

Figure 6. Treatment of HUVEC with TP508 induces NO that is inhibited by LM609.

Confluent six-well dishes of HUVEC were treated with 20 μM A23187 or 150 μg/ml TP508 (TP) for 1 h in the absence or presence of 10 μg/ml LM609. A volume of 50 pi of medium was removed, and NO levels tested with a Sievers 280i NOA. n=4, (*p <0.05).

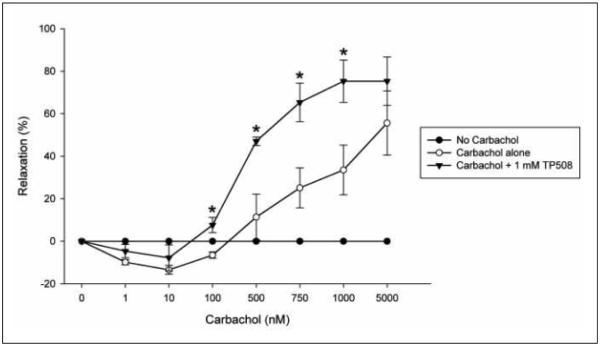

TP508 enhances carbachol-induced relaxation

Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of aortic rings has been shown to be mediated through NO. To demonstrate that TP508-induced production of NO can lead to smooth muscle relaxation, the effect of TP508 treatment on rat aortic rings was examined in a muscle bath system. Isolated rat aorta rings were pretreated with or without 2.3 mg/ml (1 mM) TP508 for 1 h. Rings were then contracted with 500 nM norepinephrine followed by treatment with increasing doses of carbachol. As anticipated, the increasing doses of carbachol increased the extent of aortic ring vasorelaxation (▶Fig. 7). TP508 pretreatment enhanced carbachol-induced relaxation compared to rings not treated with TP508. TP508 pretreated rings challenged with a cumulative 750 nM carbachol dose relaxed by 61% compared to 20% relaxation observed in the non-treated rings. TP508 pretreated rings challenged with a cumulative 1,000 nM carbachol dose relaxed by 80% compared to 32% relaxation response observed in the rings not treated with TP508. Thus, TP508 pretreatment resulted in a statistically significant enhancement of carbachol-induced relaxation in rat aorta rings at 750 nM and 1,000 nM concentrations of carbachol compared to untreated rings. Control rings that were treated with norepinephrine alone remained contracted (0% relaxation), indicating vasorelaxation occurred only in response to carbachol treatment.

Figure 7. TP508 enhances carbachol-induced vasorelaxation.

Rat aortic rings, endothelium(+) were pretreated with (black triangles) or without (open circles) 2.3 mg/ml (1 mM) TP508. Rings were then treated with 500 nM NE for 10 min followed by increasing doses of carbachol (0, 1, 10, 100, 500, 750, 1,000, 5,000 nM). Control sample represents rings not treated with carbachol (black circles). 0% relaxation is equal to the maximal contraction induced by 500 nM NE. Mean values shown ± sem, n= 3 aortas, (*p <0.05).

Discussion

TP508 is a biologically active synthetic peptide that represents a highly conserved 23-amino acid portion of human thrombin (14). Despite lacking the catalytic site of thrombin, TP508 reverses the effects of ischaemia in a porcine model of chronic myocardial ischaemia by increasing NO-mediated vasodilation with subsequent increases in eNOS expression and NO production (29). The molecular mechanisms by which TP508 induces NO and provides protection against ischaemic myocardial tissue damage, specifically the cellular receptor that is used by TP508, remains poorly understood.

The ability of TP508 to associate with specific integrins was examined in an effort to identify potential receptors for TP508 on the surface of endothelial cells. Due to the presence of RGD, a classic integrin binding motif, as well as work from previously published reports (15–19), the integrins αvβ3 and α5β1 were specifically targeted in these studies. Adhesion studies suggested that TP508 interacts primarily with the integrin αvβ3 as function-blocking antibodies and peptides inhibited cell adhesion to immobilised TP508. Adhesion to immobilised TP508 was RGD-dependent as no adhesion was observed to RAD-TP508 or scrTP508. Furthermore, soluble TP508 inhibited cell adhesion to an αvβ3-specific substrate but not to an α5β1-specific substrate. TP508 has previously been shown to induce migration in a dose-dependent manner in endothelial cells. Previous results have shown that migration was RGD-dependent and could be blocked by addition of LM609, providing further evidence of an interaction with integrins (18). SPR studies using purified αvβ3 were performed and the KD of the interaction was determined to be 13.8 ± 0.9 nM, which is similar to that observed with αvβ3 to its physiological ligands. The affinity of αvβ3 to vitronectin and fibrinogen has been shown to be 27 nM and 64 nM, respectively (30–31). These data underscore the efficacy of TP508 as an αvβ3-based therapeutic.

Adhesion of cells to TP508 results in an induction of integrin-mediated signalling events indicative of integrin-substrate interactions. These include an induction of pERK1/2 and pFAK as a result of adhesion of HEK-αvβ3 cells to immobilised TP508. HEK-αvβ3 cells were chosen for this experiment because they overexpress the integrin αvβ3, thus facilitating analysis of the phosphorylation state of αvβ3. Previous experiments show that integrin engagement, specifically engagement of β1, or β3 integrins, results in the induction of phosphorylated FAK and the subsequent activation of ERK1/2 (32–33). These observations support an earlier report in which TP508 treatment of monocytes and lymphocytes resulted in an induction of pERK1/2 (34). Previous studies have also shown a correlation between the activation of ERK1/2 and FAK and activation of eNOS, leading to NO production and vasodilation (35–36). In multiple experiments, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt was shown to result in activation of eNOS and induction of NO (37–38). Visfatin, a proposed therapeutic agent for treatment of VED, was recently shown to induce peNOS and NO in endothelial cells via activation of ERK1/2 and Akt (39). These studies provide evidence for the role of ERK1/2 signalling in eNOS activation and NO-induction.

TP508 can also induce release of NO by endothelial cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (29). This result was confirmed as treatment of HUVEC with 150 μg/ml TP508 resulted in a 1.6-fold induction of NO after 1 h, an event downstream of eNOS activation. The effects of TP508-mediated release of endothelial NO on the adjacent smooth muscle were tested using rat aortic segments subjected to muscle-bath assay. Carbachol induces vasorelaxation of arterial smooth muscle by increasing calcium influx with a subsequent induction of NO. Pre-treatment of aortic rings with 2.3 mg/ml (1 mM) TP508 resulted in an enhancement of carbachol-induced vasorelaxation. This observation supports the hypothesis that TP508-induced endothelial NO may lead to vasodilation of adjacent smooth muscle cells. Additional experiments are needed to examine the dynamics and dose response of TP508 in smooth muscle relaxation. These results further suggest that TP508 may have potentially beneficial therapeutic utility for the treatment of VED, where endothelium-dependent vasodilation is impaired.

The identity of the TP508 receptor has remained elusive despite extensive research. TP508 interacts with high-affinity binding sites on fibroblasts, monocytes, neutrophils, endothelial and epithelial cells (14) and has been shown to compete with thrombin binding to its receptors, PARs (40–43), indicating that identical receptors could be used by both thrombin and TP508 (14). However, if TP508 were to use a PAR as a receptor, it would do so by an unknown mechanism as it does not contain the thrombin catalytic site. Thrombin also associates with receptors other than members of the PAR family, including integrins αvβ3 and α5β1, and many of its biological effects may, in fact, be mediated through integrins (18–20). Indeed, the effect of thrombin can be blocked by function-blocking antibodies targeting specific integrins (20, 44). These observations indicate that TP508 may elicit some effects through an interaction with integrins.

Integrins play a vital role in the regulation of coronary vascular tone. Several studies involving isolated myocardial vessels used to characterise the role of integrin αvβ3 and α5β1, indicate that RGD peptides alter vascular tone in different vascular systems via dilation of smooth or skeletal muscles and control of blood flow (45). Being in contact with circulating blood, endothelial cells are continually exposed to shear stress. Additionally, changes in vascular tone can impart mechanical force on the endothelium. These cells are equipped to respond to such force by mediating biochemical signalling events. Endothelial receptors such as integrins (specifically αvβ3 and α5β1) play a role in shear stress-mediated signalling through a dynamic interaction with the extracellular matrix (36). Shear stress-induced signalling can be modulated by exogenous integrin-binding peptides or function-blocking mAbs (46). This signalling includes induction of ERK1/2, FAK, c-Src, PI3K, Akt and eNOS. Inhibition of FAK signalling with FAK antibodies impaired phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS in a flow-induced dilation model (35). These results indicate that integrins are involved in the regulation of eNOS and subsequent release of NO.

The role of integrins in maintaining myocardial vasculature tone is significant, but presently, no therapies target integrins for treatment of VED. Although reduced levels of NO are attributed to loss of vasodilation leading to VED, only a few therapeutic agents, such as L-Arginine, Visfatin and tetrahydrobiopterin, are aimed at enhancing NO-induced vasodilation for an effective reversal of VED-related conditions (3). TP508 plays a role in protecting the myocardium during ischaemic reperfusion injury in a process that involves induction of NO with enhancement of vasodilation (11–13). Most therapeutic ligands that target αvβ3 act by inhibiting ligand binding of the integrin. If utilised in clinical trials, TP508 may represent a novel class of therapeutics where integrin engagement is desired for a purpose other than inhibiting or limiting its normal function.

What is known about this topic?

TP508 can support adhesion and migration of endothelial cells.

TP508 induces eNOS phosphorylation under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Adhesion to immobilised TP508 result in an induction of phosphorylated MAPK and FAK.

What does this paper add?

TP508 interacts with αvβ3 with a KD of −13.8 nM.

Induction of NO production in endothelial cells by TP508 is inhibited by integrin function-blocking antibodies.

TP508 enhances carbachol-induced relaxation of isolated rat aorta segments.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Michael Mendelsohn (Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA) and Drs. Colleen Brophy and Padmini Komalavilas (Vanderbilt University Medical School, Nashville, TN, USA) for their extremely helpful discussions, Mrs. Rachel Martin for providing outstanding technical assistance; and Dr. Ward Brady (Arizona State University Polytechnic, Mesa, AZ, USA) for help with experimental design and statistical analysis. Drs. Tatiana Ugarova and Joyce Cheung-Flynn received consulting fees associated with this work.

Financial support:

This work was funded entirely by Capstone Therapeutics (Tempe, AZ, USA).

References

- 1.Lerman A, Burnett JC., Jr Intact and altered endothelium in regulation of vasomotion. Circulation. 1992;86:III12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circulation research. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadi HA, Carr CS, Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vase Health Risk Manag. 2005;1:183–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Takamisawa I, Yoshimasa Y, et al. Association between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes and the effects of pioglitazone. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2007;76:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rikitake Y, Kim HH, Huang Z, et al. Inhibition of Rho kinase (ROCK) leads to increased cerebral blood flow and stroke protection. Stroke. 2005;36:2251–2257. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000181077.84981.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd-Jones DM, Bloch KD. The vascular biology of nitric oxide and its role in atherogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:365–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egashira K. Clinical importance of endothelial function in arteriosclerosis and ischemic heart disease. Circ J. 2002;66:529–533. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz SD, Hryniewicz K, Hriljac I, et al. Vascular endothelial dysfunction and mortality risk in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:310–314. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153349.77489.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulanger CM. Secondary endothelial dysfunction: hypertension and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:39–49. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonsen U, Rodriguez-Rodriguez R, Dalsgaard T, et al. Novel approaches to improving endothelium-dependent nitric oxide-mediated vasodilatation. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fossum T, Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Mertens M, et al. TP508 (Chrysalin) reverses endothelial dysfunction and increases perfusion and myocardial function in hearts with chronic ischemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2008;13:214–225. doi: 10.1177/1074248408321468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osipov R, Bianchi C, Clements R, et al. Thrombin fragment (TP508) decreases myocardial infarction and apoptosis after ischemia reperfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:786–793. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osipov R, Robich M, Feng J, et al. The effect of thrombin fragment (TP508) on myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury in hypercholesterolemic pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1993–2001. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00071.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glenn K, Frost G, Bergmann J, et al. Synthetic peptides bind to high-affinity thrombin receptors and modulate thrombin mitogenesis. Pept Res. 1988;1:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bar-Shavit R, Sabbah V, Lampugnani MG, et al. An Arg-Gly-Asp sequence within thrombin promotes endothelial cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:335–344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papaconstantinou M, Carrell C, Pineda A, et al. Thrombin functions through its RGD sequence in a non-canonical conformation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29393–29396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Shavit R, Eskohjido Y, Fenton JW, 2nd, et al. Thrombin adhesive properties: induction by plasmin and heparan sulfate. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1279–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsopanoglou N, Papaconstantinou M, Flordellis C, et al. On the mode of action of thrombin-induced angiogenesis: thrombin peptide, TP508, mediates effects in endothelial cells via alphavbeta3 integrin. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:846–857. doi: 10.1160/TH04-04-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsopanoglou NE, Andriopoulou P, Maragoudakis ME. On the mechanism of thrombin-induced angiogenesis: involvement of alphavbeta3-integrin. American journal of physiology. 2002;283:C1501–1510. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00162.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sajid M, Zhao R, Pathak A, et al. Alphavbeta3-integrin antagonists inhibit thrombin-induced proliferation and focal adhesion formation in smooth muscle cells. American journal of physiology. 2003;285:C1330–1338. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00475.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stouffer GA, Smyth SS. Effects of thrombin on interactions between beta3-integrins and extracellular matrix in platelets and vascular cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2003;23:1971–1978. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000093470.51580.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yakubenko VP, Lishko VK, Lam SC, et al. A molecular basis for integrin alphaM-beta 2 ligand binding promiscuity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48635–48642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yakubenko VP, Yadav SP, Ugarova TP. Integrin alphaDbeta2, an adhesion receptor up-regulated on macrophage foam cells, exhibits multiligand-binding properties. Blood. 2006;107:1643–1650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharya S, Fu C, Bhattacharya J, et al. Soluble ligands of the alpha v beta 3 integrin mediate enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins in adherent bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16781–16787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle JG, Logan PJ, Ewart MA, et al. Rosiglitazone stimulates nitric oxide synthesis in human aortic endothelial cells via AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11210–11217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komalavilas P, Penn RB, Flynn CR, et al. The small heat shock-related protein, HSP20, is a cAMP-dependent protein kinase substrate that is involved in airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L69–78. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00235.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodary SC, McLean JW. The integrin beta 1 subunit associates with the vitronectin receptor alpha v subunit to form a novel vitronectin receptor in a human embryonic kidney cell line. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5938–5941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fossum TW, Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Mertens MM, et al. TP508 (Chrysalin(R)) Reverses Endothelial Dysfunction and Increases Perfusion and Myocardial Function in Flearts With Chronic Ischemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Therap. 2008;13:214–225. doi: 10.1177/1074248408321468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urbinati C, Mitola S, Tanghetti E, et al. Integrin alphavbeta3 as a target for blocking HIV-1 lat-induced endothelial cell activation in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2005;25:2315–2320. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000186182.14908.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suehiro K, Mizuguchi J, Nishiyama K, et al. Fibrinogen binds to integrin alpha(5)beta(l) via the carboxyl-terminal RGD site of the Aalpha-chain. J Biochem. 2000;128:705–710. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Q, Kinch MS, Lin TH, et al. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion activates mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26602–26605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morino N, Mimura T, Hamasaki K, et al. Matrix/integrin interaction activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase, p44erk-1 and p42erk-2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:269–273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naldini A, Carraro F, Baldari C, et al. The thrombin peptide, TP508, enhances cytokine release and activates signaling events. Peptides. 2004;25:1917–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshida R, Rocic P, Saito S, et al. Role of focal adhesion kinase in flow-induced dilation of coronary arterioles. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2005;25:2548–2553. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000188511.84138.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katsumi A, Orr AW, Tzima E, et al. Integrins in mechanotransduction. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12001–12004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mineo C, Yuhanna IS, Quon MI, et al. High density lipoprotein-induced endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activation is mediated by Akt and MAP kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9142–9149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urano T, Ito Y, Akao M, et al. Angiopoietin-related growth factor enhances blood flow via activation of the ERK1/2-eNOS-NO pathway in a mouse hind-limb ischemia model. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2008;28:827–834. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovren F, Pan Y, Shukla PC, et al. Visfatin (nicotinomide phosphoribosyltransferase/pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor) activates eNOS via Akt and MAP kinases and improves endothelial function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:El440–1449. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90780.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vu T, Hung D, Wheaton V, et al. Molecular cloning of a functional thrombin receptor reveals a novel proteolytic mechanism of receptor activation. Cell. 1991;64:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90261-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishihara H, Connolly A, Zeng D, et al. Protease-activated receptor 3 is a second thrombin receptor in humans. Nature. 1997;386:502–506. doi: 10.1038/386502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahn ML, Zheng YW, Huang W, et al. A dual thrombin receptor system for platelet activation. Nature. 1998;394:690–694. doi: 10.1038/29325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu WF, Andersen H, Whitmore TE, et al. Cloning and characterization of human protease-activated receptor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6642–6646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sajid M, Stouffer GA. The role of alpha(v)beta3 integrins in vascular healing. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hein TW, Platts SH, Waitkus-Edwards KR, et al. Integrin-binding peptides containing RGD produce coronary arteriolar dilation via cyclooxygenase activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2378–2384. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shyy JY, Chien S. Role of integrins in endothelial mechanosensing of shear stress. Circulation Res. 2002;91:769–775. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038487.19924.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]