Abstract

Background

Improving child health and wellbeing in England was the key focus of the Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2012, which recommended that all children with long-term conditions (LTCs) have a named GP responsible for their care. Little is known, however, about practitioners’ views and experiences of supporting children with LTCs in primary care.

Aim

To explore practitioners’ views of supporting children with LTCs and their families in primary care.

Design and setting

Qualitative interview study in primary care settings in South Yorkshire, England.

Method

Interviews explored practitioners’ views and experiences of supporting children with asthma, cystic fibrosis, type 1 diabetes, and epilepsy. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using the framework approach.

Results

Nineteen practitioners were interviewed: 10 GPs, five practice nurses, and four nurse practitioners. The GPs’ clinical roles included prescribing and concurrent illness management; nurse practitioners held minor illness clinics; and practice nurses conduct asthma clinics and administer immunisations. GPs were coordinators of care and provided a holistic service to the family. GPs were often unsure of their role with children with LTCs, and did not feel they had overall responsibility for these patients. Confidence was dependent on experience; however, knowledge of GPs’ own limits and accessing help were felt to be more important than knowledge of the condition.

Conclusion

Primary care has a valuable role in the care of children with LTCs and their families. This study suggests that improving communication between services would clarify roles and help improve the confidence of primary care practitioners.

Keywords: child health, chronic disease, long-term conditions, primary health care, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

The UK has the second highest child mortality rate in western Europe. Five deaths per day could be avoided if the UK was on equal terms with the country with the lowest mortality rate.1 The cause of this disparity in levels of health throughout Europe is multifactorial, and suggested reasons include inequalities within the country,2 the delivery and funding of health care,3 and training in the primary care workforce.4 In the UK there is an unexplained variation in outcomes across a range of children’s health services.5 The Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report highlights current healthcare problems in England and provides recommendations. The 2012 report focused on improving child health, and recommended that all children with long-term conditions (LTCs) have a named GP responsible for their care, in order to benefit from increased continuity.6

Four index conditions — asthma, cystic fibrosis, type 1 diabetes, and epilepsy — were explored in this study to reflect a range of paediatric LTCs in relation to prevalence and diversity of management strategies. Asthma is the most common childhood LTC7 usually managed in UK primary care, by practice nurses;8 diabetes has a well-defined secondary care managed system;9 epilepsy is managed in secondary care, with primary care involvement;10 and cystic fibrosis is managed in specialist centres,11 with only 274 children diagnosed in 2012.12

Potential roles for primary care indicated in the literature include diagnosis and referral,13 prescribing and medication review, education14 (especially sexual health),15,16 psychosocial support for child and family,17 acting as the coordinator of care,18 providing terminal care,19 and asthma management (by nurses).8 Furthermore, barriers to the role of primary care include: practitioners’ fear of managing these conditions,19 an apparent lack of knowledge of complex conditions,19 and poor communication between services with complex, fragmented care systems.18 This literature was mainly opinion-based, however, there is scant literature regarding GPs’ and nurses’ views concerning providing this role, and the challenges they face, hence a qualitative approach was taken.

The subsequent research question of this study was: ‘What is the role of primary care in supporting children with long-term conditions and their families?’. The aim was to explore GPs’ and practice-based nurses’ perspectives about the role of primary care in children with the four index conditions mentioned previously.

METHOD

Study design

This was a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews to collect data. The topic guide (Box 1) was developed with reference to the literature review and sensitising concepts,20,21 and was refined using a focus group with four academic GPs. One of the authors kept a reflexive diary to understand and reduce potential sources of bias.

Box 1. Topic guide used with all participants.

| Section | Domain of enquiry |

|---|---|

| Professional background and current role |

|

| Current practice in caring for children with LTCs |

|

| Current practice in caring for families of children with LTCs |

|

| Experiences of your role working with children with LTCs |

|

| Link between primary and secondary care |

|

LTCs = long-term conditions.

Sampling and recruitment

The sample for this study was GPs, nurse practitioners, and practice nurses in South Yorkshire (England), obtained by convenience sampling. Participants were initially recruited at an education event in Sheffield, attended by 260 practitioners. Posters were placed where GP tutors ran teaching sessions. Emails were sent to all GPs who acted as tutors for Sheffield Medical School. Medical students on primary care placements were given flyers to hand to potential participants. The Sheffield Practice Nurse Forum was contacted to recruit nurses. A snowballing technique was used to encourage those who participated to identify other GPs or nurses who might be interested.

How this fits in

The Chief Medical Officer for England recommended that all children with long-term conditions (LTCs) have a named GP. To date, few researchers have explored, in detail, practitioners’ views and experiences of managing childhood physical LTCs in primary care. This study reveals that primary care practitioners are often unsure of their roles with children with LTCs, and do not feel they have overall responsibility for these patients. However, knowing their own limits and how to access help were felt to be more important than knowledge of the condition. This study suggests that improving communication between services may clarify roles and help improve the confidence of primary care practitioners.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection was by semi-structured interviews; 17 were conducted face to face at the participant’s surgery or at the research unit, and two were conducted by telephone. Interviews lasted 29 minutes on average (range 20–37 minutes). Practitioners were asked about their role in relation to children with LTCs and their families, their perceptions of the link between services, and their feelings about providing this care. Interviews were audiorecorded with consent and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis was undertaken using the framework analysis approach,22 which enables investigation of previously known issues while simultaneously allowing for identification of newly-emergent ideas. The topic guide was refined throughout data collection, taking account of ongoing analysis in order to incorporate and explore emergent issues. Data collection and analysis took place simultaneously. Transcripts underwent coding by one author with a consensus reached regarding the core themes within the research team (all the authors). Individual transcripts were mapped onto the framework using NVivo (version 10). Sampling continued until main data categories were saturated and no new insights were apparent. A final member check was used with two GP participants: one GP who had been in the initial focus group and one GP who had no involvement thus far.

RESULTS

Nineteen healthcare professionals were interviewed: 10 GPs, five practice nurses, and four nurse practitioners (Table 1). The participants had a wide range of previous experience, education, and roles. Nine of the 10 GPs had undertaken postgraduate paediatric training. Six of the nine nurses had previously worked in secondary care.

Characteristics of the study practices’ patient population and the participants interviewed (n = 14)

| Practice (n= 14) | |

|---|---|

| Deprivation decile20 | |

| Deprived (1–3) | 4 |

| Mixed (4–7) | 8 |

| Affluent (8–10) | 2 |

|

| |

| Participants (n= 19) | |

|

| |

| Professional group (self-defined) | |

| GP | 10 (6 male, 4 female) |

| Nurse practitioner | 4 (all female) |

| Practice nurse | 5 (all female) |

|

| |

| Age, years | |

| 30–39 | 5 |

| 40–49 | 6 |

| 50–59 | 5 |

| ≥60 | 3 |

| Range | 30–63 |

|

| |

| Years since qualification | |

| <5 | 5 |

| 6–10 | 4 |

| 11–20 | 3 |

| 21–30 | 5 |

| 31–40 | 2 |

| Range | 1–33 |

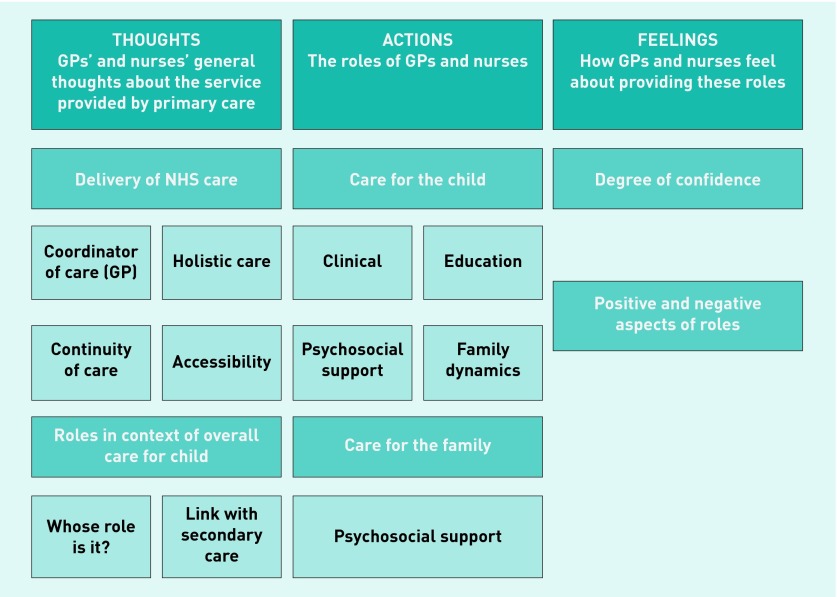

Three meta-themes were developed from the data: practitioners’ thoughts, actions, and feelings (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of results by meta-theme.

GPs’ and nurses’ thoughts about the service provided

Delivery of NHS care

The overarching concepts of coordination, accessibility, continuity, and holistic care were central to delivery of care. The GPs felt themselves to be the coordinators of care for children with LTCs, particularly when describing their role in relation to secondary care:

‘I think the role is really to try and coordinate care often, so it’s looking at the bigger picture and taking a holistic approach to the child. So you’re, you know, they may well be under a community paediatrician or a paediatrician in hospital, they may have specialist nurses involved. But I think really the GP’s role is to ... try and help coordinate and support the family, in sort of, and liaising with social care sometimes as well, to try and provide a good package of care for that child.’

(GP13)

GPs thought they had the ability to signpost to services because they have a good understanding of the NHS and the ‘system’.

Holistic care was described by all of the participants. Holism was key, especially for the conditions with a large amount of input from secondary care:

‘So cystic fibrosis, I would expect us not to have much to do with the cystic fibrosis, but quite a lot to do with the family, and the wellness and health of the individual.’

(GP5)

The nurses felt that it was important to encourage the accessibility of primary care:

‘I always stress to people, “look I’m just on the other end of the phone, if you have any questions, anything you think about when you’ve left, you only need to phone and I shall get back to you as soon as I can”.’

(PN17)

Continuity was important to all of the participants. GPs thought that long-term relationships improved recognition of psychosocial issues and also improved patient satisfaction with services:

‘I mean I may have had spells of a year where I’ve not seen that child with cystic fibrosis, but at least when you do see that child, you’ve got a kinda a little bit of an understanding of the background to the diagnosis, sometimes the kind of family dynamics and very often other members of the family will be our patients as well.’

(GP3)

However, both nurses and GPs discussed the negative effect of changes to the NHS on their practice, which were impacting on continuity:

‘Well it’s like, what we lack here a bit, because we’re so big, is continuity. So they see somebody different every time they came, erm and that isn’t helpful ...’

(NP8)

Related to continuity, the named GP idea was discussed. All GPs and nurses thought this was a helpful idea because of the potential benefits of improved continuity. However, they thought implementation would be difficult, due to availability of acute appointments and the GP being on holiday or sick leave. They also identified that it was important that the families had choice when deciding on the named GP:

‘Yeah, well I guess it’s similar to adults with you know, complex, two, three, four long-term conditions having a named GP, erm I think there would need to be certain improvements with communication, education of GPs in what our role is on, erm, how we can really offer the best service. I’m not averse to that, I think it’s a good idea in principle. Erm, but it’s having the resources to be able to do that, and I’m not quite sure what that would involve either you know, having a named GP, what does that mean? Do we see them x times a year, are we the first port of call if there are problems, you know ... how would we liaise with, work with their named paediatrician?’

(GP13)

Roles in context of overall care for child

The overall definition of the role of primary care in supporting children with LTCs was varied. Responsibility was a term referred to by four of the GPs. One GP stated that he had overall responsibility for the child as he was their family doctor:

‘We’re the GPs and it’s our responsibility ... Like I say, if you’ve got a child with diabetes, you could say well if they’re looked after by the hospital it’s their responsibility, but it’s not, they’re our patients.’

(GP6)

However, another GP felt that secondary care ‘own’ patients, and he felt that this would limit his role in caring for the patients:

‘Same with CF [cystic fibrosis], I know that they’re very possessive about their CF patients, so we’re not going to suddenly change the antibiotics you know.’

(GP9)

Furthermore, a number of practitioners stated that they were unsure that secondary care staff knew what they could provide in primary care:

‘I would struggle to think that they know exactly what we can offer, and they probably underestimate what we can offer. Is my feeling.’

(GP13)

One GP described feelings of uncertainty about her own role within the wider care:

‘And it’s what is our niche? ... as a GP identifying our role is sometimes sort of not always that clear. Erm, so yeah, some sort of, niggles of uncertainly sometimes because you think “I’m not sure, are the hospital taking care of this or are we getting involved with this?”, so very often you might feel a little bit disengaged from their care because it all seems, a lot of it seems to be done external to the practice, so that can make you, make me feel a little uneasy sometimes.’

(GP13)

Communication between primary and secondary care was felt to be variable and to potentially impact on the care of the child, especially when letters were delayed:

‘Yeah, obviously it would be really helpful to have up-to-date information, especially if a child’s been admitted, you know, and you want to see what’s been done on the admission ... because parents don’t always remember all the details.’

(PN17)

There were examples of families bridging the gaps between services, despite GPs stating that they were the coordinators of care. Practitioners would remind families to discuss attendances to primary care with secondary care, as they have no standardised method of informing the specialist team:

‘If we treat them, here and now, we wouldn’t let them know, either. Yeah, well we’d maybe say to the parents “don’t forget to mention it when you go to the hospital” but we wouldn’t send a task.’

(NP19)

Both GPs and nurses felt that personally knowing the staff in secondary care was beneficial for their confidence in managing these conditions. In order to improve the link between services, a number of GPs and nurses felt that technology could help. Some suggestions included routine email access and videoconferencing with specialists, and collaboration of electronic notes:

‘You could say “seen this child” just task ‘em, a quick instant message, just to let them know and it can go in the records for next time they’re seen there.’

(NP19)

Actions: the roles of GPs and nurses

Care for the child

The main clinical reason a GP would see a child with a LTC is for concurrent illness, although they may see acute exacerbations of the LTC. GPs prescribe for these children, and conduct medication reviews, but these may not be face to face. The nurse’s role involved the routine care of children with asthma or any children for immunisations. The nurse practitioners run minor illness clinics and may see children with LTCs for concurrent illness.

Education was a key role for the nurses regarding asthma, and they felt that this should be provided at every opportunity. However, time pressures in primary care were felt to impact on this provision:

‘Mmm, yeah, it’s really hard to educate people very much in 10 minutes, isn’t it?’

(NP8)

The GPs prescribe medication for children’s LTCs, usually at the request of the specialists. They thought that although the decision about what to prescribe is made in hospital, responsibility comes down to them:

‘In terms of ongoing prescribing for, say, their insulin, for things like that, yes we do that. So therefore it does come back to our responsibility I suppose, and we need to know what we’re doing.’

(GP11)

GPs provide medication reviews, aiming to identify child or family concerns. A few GPs referred to the review as a time to find out how the child is more generally, and to provide some level of education:

‘So you’re checking, well, you’re checking compliance, really, erm, you know, are they happy with the medications they’re on, do they understand why they’re taking them, do they have any problems with them, is there anything else we should be doing? And we also use the medication review as a general opportunity to talk about wider issues and the condition in general, I think.’

(GP11)

However, many GPs had not completed reviews themselves for children with conditions managed in secondary care. One GP suggested that children with LTCs are not being seen face to face and that the review would be opportunistic:

‘With those guys who don’t tend to come see us, like the cystic fibrosis ones, we often give them a bell every now and again to check how they are doing. It’s often when they’ve got a discharge summary, and there’s quite a big change to their medication, it’s courtesy to ring them up and say “look, we’ve got this letter through, how are you doing, and what quantities do you need?”. Erm, but again, we might not see them for months on end.’

(GP9)

Education provided by the GPs to children with cystic fibrosis, epilepsy, and type 1 diabetes was regarding services and accessing care. There was no discussion about sexual health:

‘We should be supporting them, being a point of contact, helping them to negotiate the system, so to speak.’

(GP11)

GPs and nurses recognised the burden on children, and felt they should support these children emotionally:

‘... so I guess it’s looking at, not only their physical problems, and you know, how they may feel about things as well, so their emotional wellbeing, often these, you sort of focus on. Especially I think with certainly with diabetic kids I’ve been involved with, you know there’s a massive psychological burden for those children, and a big change in lifestyle.’

(GP13)

Care for the family

GPs and nurses have a role in assessing family concerns, which may be broader than the issues raised with secondary care services in relation to the child. This was encouraged by the perception that secondary care services are not providing psychosocial support for the family:

‘You know, if you’re seeing a paediatrician and you’re telling them how stressed you are as an adult, as a parent, they can empathise and they can possibly put you in the direction of some kind of group or support network that might help. But there may be something else going on there that they need a bit of help with or support, like a counsellor or a regular review with us, or maybe something even more, medication wise, whatever. That will come from us, so ultimately it may be more sensible for that to happen here, because we’re more capable of doing something about it, than perhaps some of the other services are.’

(GP9)

Feelings regarding providing these roles

Confidence

Participants reported feeling less confident caring for children than adults, which was even more pronounced for children with LTCs that GPs perceived they knew less about:

‘We all feel, well, I certainly feel more concerned not to make a mistake, you know, to get it right, not to miss anything serious and so on. In the sense that you know, they are relatively more precious to people at the stage, I know life shouldn’t be like that, but generally speaking as a group, people naturally get very concerned about children, and very protective towards children.’

(GP2)

‘So again, it is quite specific for the conditions. And again, on the skill sets, I wouldn’t know where to start managing a cystic fibrosis person from scratch, I shouldn’t be expected to. But I would know an asthmatic, I would have an idea about diabetes but not as good as asthma.’

(GP9)

Conversely, one GP felt more confident managing a child with a LTC because of the availability of information and access to extra help, and also because it was likely that he would have met the child before, and know the family.

A number of the more experienced GPs recognised the importance of knowing their own limits and having an awareness of where to seek advice, and felt that this was more relevant than their knowledge of the condition:

‘... so am I confident about looking after something very unusual? No. But I am confident in knowing what I don’t know and what the family might want to know.’

(GP5)

Positive and negative aspects of role

Participants felt that working with children with LTCs and their families was fun and rewarding, but they particularly enjoyed the long-term relationship:

‘And I love building up a relationship with the family, and getting to know them a bit.’

(PN7)

Negative aspects for the nurses included patient non-compliance, which they found frustrating. Many of the participants also discussed issues around difficulties caring for children with LTCs and around terminal care:

‘I think as a parent as well, you bring your own stance to things as well because you think ‘oh well it must be really difficult for the family’. Not feel sorry for them, but you can empathise with the fact that they’re, they have a struggle every day, and every day is a bit of a battle with the more complex patients.’

(GP13)

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study reveals that primary care practitioners believe that they are the coordinators of care, but are often unsure of their roles and responsibilities in supporting children with LTCs. Practitioners feel that knowing their own limits and how to access help is more important than knowledge of the condition. Interestingly, the participants exhibited discrepancies in what they perceived they were doing for these children, and what they actually reported in the action theme; for example, GPs were prescribing but not providing medication reviews. This study suggests that improving communication between services would help clarify roles and help improve the confidence of primary care practitioners.

Strength and limitations

A reflexive diary and audit trail provides records of the credibility of this research. Data saturation was reached with five nurses and seven GPs, improving trustworthiness.23 The use of member checking (discussing the interpretation of the results with subjects) also improves credibility.

It is likely that this study included GPs who had an interest in child health or were more involved in the care of children with LTCs compared with ‘average’ GPs. Nine of the 10 GPs had completed postgraduate paediatric training, compared with under 50% nationally.4 However, the participants were diverse in terms of practice deprivation and years since they had qualified.

Comparison with existing literature

In this study, when GPs discussed their role with children with cystic fibrosis, epilepsy, and type 1 diabetes, GPs perceived their main role as being the ‘hub’ or coordinator of care. This finding agreed with the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Child Health Strategy 2010–2015, which supports the view that coordination of services is key.24 However, there was a diverse range of views about who is responsible for children with LTCs, with GPs recognising that they may ‘assume’ that secondary care are providing certain roles. This reflects McDonagh’s view that GPs may be unsure of their role, and leave certain matters to secondary care.25

However, this study suggests that many factors including GPs’ experience and how they perceive the link with secondary care impacted on GPs’ views of their role. Consistent with published research, this suggests that the roles and responsibilities of primary care need to be better defined.19,26 It is evident that primary care professionals perceive that those working in secondary care are unaware of what they can provide, suggesting that better links between services would enable enhanced definitions of roles. The nurses, however, were found to have a clearly defined role with children with asthma, and were generally not involved with the care of children with the other LTCs in the study.

Confidence was identified as a key issue in the literature review when discussing the role of primary care, and was viewed as a barrier to the use of primary care services in supporting children with LTCs.19 It was evident from the GPs that their experience had the greatest impact on their perceived confidence.

Pennell and David discussed barriers to the involvement of GPs in cystic fibrosis care,19 which many of the participants also described. The GPs agreed that they lacked detailed knowledge of the LTCs. Poole et al.27 also described how families also perceive lack of GPs’ specialised knowledge to be a problem. However, the participants in this current study stated that since their role was not disease management for these LTCs, specialist knowledge was less relevant. In a primary care context, confidence was dependent on the GP knowing their limits and where to access support, rather than having specialist knowledge of the condition. Professionals with personal knowledge of secondary care staff find it easier to ask for help, hence, will be more integral to, and confident in, managing these conditions.

Implications for practice and research

The views of the practitioners in this study allowed for the development of a number of recommendations to improve primary care for children with LTCs in the UK:

Implementation of the ‘named’ GP policy. At diagnosis a GP should be assigned to the family, with a view to taking the lead in communication with secondary care. This role can be paired for cross-cover, in order to manage GP leave.

Specialist services to contact the named GP. The specialist nurse and consultant should be encouraged to make personal contacts with the named GP to help further define roles on a patient-centred level.

Longer appointments for children with LTCs. This would allow identification of concerns of the patient and family, and give staff time to update themselves regarding the child’s condition using communications from secondary care.

Integration of technology. This would improve the link between primary and secondary care; particularly to alert secondary care of a patient’s attendance to primary care.

Further research. There is little published work exploring the views of children with LTC and their families.

This research forms part of a complex picture relating to the care of children with LTCs and their families which warrants further exploration.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all the participants, the Academic Unit of Primary Medical Care at the University of Sheffield, especially Caroline Mitchell and Helen Twohig for reviewing early versions of the manuscript, and finally to the Henry Bottom Charitable fund for helping Anna Willis to complete her BMedSci intercalation year.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was sought from, and approved by, the University of Sheffield’s University Research Ethics Committee. (reference SMBRER281).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolfe I, Thompson M, Gill P, et al. Health services for children in western Europe. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1224–1234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Child wellbeing and income inequality in rich societies: ecological cross sectional study. BMJ. 2007;335:1080. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39377.580162.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakubowski E, Busse R. Health care systems in the EU. A comparative study. Luxembourg: European Parliament; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preparing the future GP: the case for enhanced GP training. London: RCGP; 2012. Royal College of General Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Right Care. NHS atlas of variation in healthcare for children and young people. 2012. http://www.rightcare.nhs.uk/index.php/atlas/children-and-young-adults/ (accessed 30 Jun 2015)

- 6.Davies SC. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2012. Our children deserve better: prevention pays. London: Department of Health; 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annual-report-2012-our-children-deserve-better-prevention-pays (accessed 30 Jun 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asthma UK. Asthma facts and FAQs. 2015. http://www.asthma.org.uk/asthma-facts-and-statistics (accessed 30 Jun 2015)

- 8.Lyte G, Milnes L, Keating P, Finke A. Review management for children with asthma in primary care: a qualitative case study. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(7B):123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Court JM. Issues of transition to adult care. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29(Suppl 1):S53–S55. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care CG137. London: NICE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cystic Fibrosis Trust. Cystic fibrosis clinical care pathway (draft version) 2015 http://www.cfcarepathway.com/index.htm (accessed 30 Jun 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cystic Fibrosis Trust. UK cystic fibrosis registry annual data report 2012. 2013 https://www.cysticfibrosis.org.uk/media/316760/ScientificRegistryReview2012.pdf (accessed 30 Jun 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matyka K, Richards J. Managing children with type 1 diabetes in collaboration with primary care. Diabetes and Primary Care. 2009;11(2):117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick M. SIGN guideline will improve care in childhood epilepsy. Guidelines in practice. 2005. Jun, http://www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/jun_05_kirkpatrick_jun05#.Vbd9V1qxLR0 (accessed 28 Jul 2015)

- 15.McDonagh JE. Growing up and moving on: transition from pediatric to adult care. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9(3):364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finnegan A. Sexual health and chronic illness in childhood. Paediatr Nurs. 2004;16(7):32–36. doi: 10.7748/paed2004.09.16.7.32.c939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services: children and young people who are ill. London: DH; 2004. Department of Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly A. The primary care provider’s role in caring for young people with chronic illness. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:32–36. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)91195-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennell SC, David TJ. The role of the general practitioner in cystic fibrosis. J R Soc Med. 1999;92(Suppl 37):50–54. doi: 10.1177/014107689909237s09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Public Health England. National general practice profiles. 2015 http://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/general-practice (accessed 30 Jun 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowen GA. Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(3) https://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_3/HTML/bowen.html (accessed 28 Jul 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saumure K, Given LM. Data saturation. In: Given L, editor. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. pp. 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- 24.RCGP child health strategy 2010–2015. London: RCGP; 2010. Royal College of General Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonagh JE. Transition of care: how should we do it? Paediatr Child Health. 2007;17(12):480–484. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaslovsky R, Sadof M. How to best deliver care to children with chronic illness: cystic fibrosis as a model. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(6):822–828. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833faa5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poole K, Moran N, Bell G, et al. Patients’ perspectives on services for epilepsy: a survey of patient satisfaction, preferences and information provision in 2394 people with epilepsy. Seizure. 2000;9(8):551–558. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]