Introduction

Schizophrenia is a highly prevalent disorder that affects up to 1% of the population worldwide. Symptoms are divided into multiple factors, including positive, negative and cognitive (disorganization) domains. Although many individuals show excellent symptomatic response to existing medications, others suffer from persistent negative symptoms and poor long-term outcome. Furthermore, individuals with schizophrenia as a group show a significant decline in cognitive function during the years immediately preceding illness onset. Present medications have limited if any impact on cognitive function, which remains a strong independent predictor of impaired functional outcome in schizophrenia.

Currently available antipsychotics function by blocking D2-type dopamine receptors. The first effective antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was initially synthesized as an anti-histamine and its antipsychotic effects were discovered fortuitously in the 1950’s, leading to development of the dopamine model. Medications developed since then show a range of potencies and side effect profiles based upon binding at D2 versus other receptor types. Clozapine, which was first marketed in 1971, remains the gold-standard medication, although the basis for its preferential clinical profile remains unexplained. Long acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics as a class may also lead to improved therapeutic outcome relative to oral medication.

More recent models of schizophrenia focus on disturbances of brain glutamatergic neurotransmission. Glutamatergic models are based on the ability compounds such as phencyclidine (PCP) or ketamine to induce clinical symptoms closely resembling those of schizophrenia by blocking neurotransmission at N-methyl-D-aspartate-type glutamate receptors (NMDAR). NMDAR, in turn, are modulated by endogenous brain compounds including glycine, D-serine and glutathione. Small scale proof-of-principle studies have been conducted with compounds of convenience such as glycine, D-serine, or N-acetylcysteine.

The glycine reuptake inhibitor bitopertin showed encouraging results in a phase II study. However, initial phase III studies for treatment of persistent negative symptoms have been negative, although studies focusing on suboptimal treatment response remain ongoing. Other compounds may influence glutamatergic neurotransmission indirectly, for example by stimulating glutamate release via α7 nicotinic receptors. In some individuals, glutamatergic dysfunction has been linked to the presence of endogenous antibodies to the NMDAR, frequently in the context of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The prevalence of autoimmune forms of schizophrenia remain unknown. However, in such individuals, specific autoimmune therapy is clearly warranted.

An increasingly important target is the development of compounds to reverse symptoms early in the disorder and to prevent progression to psychosis. Glutamatergic excess may predominate early in the disease and lead to volume reduction in key brain regions such as superior temporal cortex or the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Treatments aim at reversing glutamatergic hyperactivity, either by correcting underlying NMDAR dysfunction or modulating presynaptic glutamate release, might therefore be important new treatment approaches for use in individual at high clinical risk for schizophrenia.

Finally, increasing evidence suggests that glutamatergic function can be modulated by non-invasive brain stimulation approaches such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Inhibitory-based brain stimulation targeted at auditory brain regions may be effective in treatment of persistent auditory hallucinations. Investigational approaches are needed to restore cortical plasticity as a means of reversing persistent neurocognitive dysfunction.

Diet and lifestyle

Diet and lifestyle are important and often overlooked factors in schizophrenia. Positive and disorganized symptoms may lead to a neglect in general health, while negative symptoms may undermine desire for regular activity and exercise. Antipsychotic treatment is also associated with weight gain that may further erode activity. Although management of diet and lifestyle is not sufficient of itself to control schizophrenia, nevertheless, attention to these aspects may optimize brain function, improve quality of life and reduce excess mortality [1, 2] commonly associated with schizophrenia.

Efficacy of exercise in schizophrenia is supported by randomized, controlled clinical trials [3]

Exercise-induced increases in hippocampal volume in schizophrenia are linked to improved short-term memory [4]

Genetically based disturbances in folate metabolism may also be linked to negative symptoms [5], age of onset [6], and risk for weight gain [7]; metabolic syndrome [8]

Elevated homocysteine levels [9, 10] may increase oxidative stress [11] and lead to inhibition of NMDAR-mediated neurotransmission [12]

Genetic dysregulation of glutathione synthesis may also lead to increased brain oxidative stress [13]

Treatment with folic acid + vitamin B12 may lead to improved negative symptoms in individuals with genetic alterations in folate absorption [14, 15]

Pharmacological treatment

Pharmacological management remains the mainstay treatment for schizophrenia. Pharmacological treatment should be based on well-defined target symptoms. Symptoms of schizophrenia are typically divided into positive, negative and cognitive (disorganized) factors, along with depression and excitement. Cognitive dysfunction, as measured using tests such as the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery [16] or Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia [17] represents an independent domain of psychopathology, and is associated with poor long-term outcome. Both positive and negative symptoms may persist despite antipsychotic treatment. Persistent negative symptoms are particularly associated with poor outcome. Antipsychotics are without demonstrated efficacy on neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia, which remain a cause of persistent social and occupational disability.

Antipsychotics function primarily by inhibiting activity of dopamine at D2-type dopamine receptors.

Activity at other receptors leads to differences in side effect profile and tolerability, but no systematic effect on efficacy. Liability for all-cause-discontinuation, weight gain, extrapyramidal side-effects and prolactin increase vary significantly across compounds [18]

Risk of symptom recurrence following medication discontinuation is extremely high (~90% at 2 yr, [19–21], and therefore should be done with extreme caution.

Pharmacogenetics at present are more effective at predicting susceptibility of side effects than of therapeutic benefit [22]

Although polypharmacy is common, it is not supported by clinical evidence [23, 24].

Use of benzodiazepines, while common, has not been shown to have antipsychotic efficacy [25]

Anti-depressants may treat depressive symptoms, but are generally without effect on positive or negative symptoms [26]

Long-acting injectable anti-psychotics are probably underutilized [27–29] and should be considered even in early stage patients [30]. Use of LAI significantly reduces risk of relapse in effectiveness studies [31].

However, RCTs of LAI vs. oral medications typically do not show an advantage [32], potentially due to patient selection factors and higher rates of adherence observed in clinical trials vs. routine clinical practice [33]

LAI treatments also effective in children and adolescents with psychosis [34, 35]

Clozapine remains the gold standard medication [36] and is underused [37]. Reduced risk of suicide outweighs potential consequences of agranulocyotsis [37]. Racial disparities in use of clozapine have been observed [38]

Oral Antipsychotics

Oral antipsychotics or short acting injectables are the most common starting treatments for patients with schizophrenia. Antipsychotics are divided into high vs. low potency based on liability to produce motor side effects, and into first (FGA) vs. second (SGA) generation agents based upon year of development, with risperidone, which was first marketed in 1994, generally considered the first SGA. A key exception, however, is clozapine, which was first synthesized very early during the course of antipsychotic development (1955), yet was subsequently shown in the late 1980’s to have unexpected clinical effectiveness and reduced risk for Parkinsonian side effects and tardive dyskinesia. The discovery of these atypical effects of clozapine led to the realization that even though both antipsychotic effects and Parkinsonian side effects reflect D2 blockade, the two sets of effects could be dissociated either because of regional specificity of the D2 blockade itself, or regionally specific mitigation effects.

A second nomenclature that attempts to capture the distinction between different classes of agent is division of compounds into “typical” vs. “atypical” agents, based upon reduced risk for extrapyramidal side effects. Different atypical antipsychotics have different underlying pharmacologies. Based upon the high affinity of clozapine for 5-HT2A receptors, one approach to atypical antipsychotic development was synthesis of compounds with high potency at 5-HT2A receptors relative to D2 receptors. Examples of such compounds include risperidone; 9-OH risperidone (aka paliperidone), olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, lurasidone, or iloperidone. In contrast, aripiprazole and the more recently developed compound cariprazine [39] have reduced extrapyramidal side effects because of intrinsic D2 agonism, which may, however, limit their antipsychotic efficacy for some subjects. Other receptors including D3 [39] and 5-HT1A [40] may also play a role in efficacy and tolerability. A comprehensive discussion of the role of specific receptors in antipsychotic atypicality has recently been published [41].

The complex pharmacology of SGAs also leads to increased susceptibility for specific side effects including weight gain and QTc prolongation. Furthermore, despite the attempt of the SGAs to recreate the superior clinical potency of clozapine, to date this quest has been unsuccessful. Two large effectiveness studies, CATIE [42] in the US and EUFEST [43] in Europe, as well as recent meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [18] failed to show superiority of second generation; atypical agents over first generation; typical agents. A more useful approach to the typical; atypical nomenclature is subclassification of compounds according to antipsychotic efficacy vs. liability to induce specific types of side effects, including 1) weight gain; metabolic syndrome, 2) extrapyramidal side effects, 3) prolactin increase, 4) QTc prolongation, or 5) sedation.

Clozapine remains the only compound with clearly superior efficacy. According to recent meta-analyses [18], other compounds with somewhat superior efficacy compared to the class as a whole include amisulpiride, olanzapine and risperidone. The somewhat greater efficacy of olanzapine was also reported in the CATIE [42] and EUFEST [43] trials. Nevertheless, olanzapine and clozapine have highest rates of weight gain, while haloperidol, ziprasidone and lurasidone are relatively weight neutral. By contrast, haloperidol, chlorpromazine and lurasidone have relatively high rates of extrapyramidal side effects, and risperidone; paliperidone show high risk for prolactin elevation.

Thus, decisions regarding compounds should be based upon trade-off of different side effects for individual patients rather than FGA; SGA or typical; atypical antipsychotic distinction, and some compounds such as perphenazine or haloperidol remain viable compounds despite between typical FGA agents. Interestingly, all-cause discontinuation is lowest with compounds that show the greatest clinical efficacy (e.g. amisulpiride, olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone), suggesting that discontinuation decisions are driven primarily by efficacy, rather than tolerability issues. Although SGAs were markedly more expensive that FGAs when first introduced, many such as risperidone and olanzapine are now available in generic formulation and cost <$1.00/d. Cost effectiveness debates, therefore, no longer center on relative cost of SGAs vs. FGAs, but rather on cost of newer, proprietary SGAs (e.g. asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, cariprazine) vs. generic SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine). While proprietary compounds may be more effective for individual subjects, nevertheless, newer SGAs as a group have not been shown to be superior to the original SGAs that are now available in generic form.

Standard dosage: The standard dosage varies by compound. Consensus criteria are available in [44, 45] (see Table 1)

TABLE 1.

| Compound | Trade name | CPZ equiv |

Dose (mg/d) |

Maintenance (mg/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First generation (FGA) | ||||

| Fluphenazine | Prolixin | 2 | 6–20 | 6–12 |

| Trifluperazine | Stelazine | 15–50 | 15–30 | |

| Perphenazine | Trilafon | 10 | 30–100 | 30–60 |

| Mesoridazine | Serentil | 50 | 150–400 | 150–300 |

| Chlorpromazine | Thorazine | 100 | 300–1000 | 300–600 |

| Thioridazine | Navane | 100 | 300–800 | 300–600 |

| Haloperidol | Haldol | 2 | 6–20 | 6–12 |

| Thiothixene | Navane | 5 | 15–50 | 15–30 |

| Molindone | Moban | 10 | 30–100 | 30–60 |

| Loxapine | Loxitane | 10 | 30–100 | 30–60 |

| Second generation (SGA) | ||||

| Clozapine | Clozaril | 150–600 | 150–600 | |

| Risperidone | Risperidal | 2–8 | 2–8 | |

| Paliperidone | Invega | 3–15 | 3–15 | |

| Olanzapine | Zyprexa | 10–20 | 10–20 | |

| Quetiapine | Seroquel | 300–750 | 300–750 | |

| Ziprasidone | Geodon | 120–160 | 80–160 | |

| Aripiprazole | Abilify | 10–30 | 10–30 | |

| Asenapine | Sepharis | 10–20 | 10–20 | |

| Iloperidone | Fanapt | 12–24 | 12–24 | |

| Lurasidone | Latuda | 40–160 | 40–160 | |

| Cariprazine | 1.5–12 | 1.5–9 | ||

| Long acting injectables (LAI) | ||||

| Fluphenazine decanoate | Modecate | 12.5–25 | 12.5–100 (/2 wks) | |

| Haloperidol decanoate | Haldol | 100 | 100–450 (/4 wks) | |

| Risperidone microspheres | Risperidol consta | 251 | 25–50 (/2 wks) | |

| Paliperidone palmitate | Invega Sustenna | 234 day 1; 156, day 7 | 39–234 (/4 wks) | |

| Olanzapine pamoate | Zyprexa Relprevv | 300 | 300 (/2 wks) | |

| Aripiprazole suspension | Abilify Maintena | 4002 | 300–400 (monthly) |

supplemental oral medication needed × 3 wks;

supplemental oral medication needed × 2 wks

Contraindications: Known or past failure of antipsychotics. History of neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Main drug interactions: Extensively metabolized by microsomal P450 enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2 and CYP3A4/5. Genomic variability in these enzymes may lead to variations in drug metabolism and susceptibility to side effects [22, 46, 47]

Special points: The availability of special formulations such as rapid acting IM or sublingual tablets may contribute to treatment decisions.

Cost-effectiveness: Highly cost effective, given risk of relapse following discontinuation. SGAs probably cost effective vs. FGAs, given lower rates of discontinuation. Cost effectiveness of proprietary vs. generic SGAs not established.

Class of drugs: Long activity injectable (LAI) antipsychotics

LAIs have the advantage of higher adherence rates and more stable plasma levels. The first LAIs introduced, fluphenazine in 1972 and haloperidol in 1986, were high potency typical antipsychotics and thus had the disadvantage of high risk for EPS. The first injectable SGA, risperidone, was a microencapsulated formulation that required 3 weeks to begin releasing compound, and thus was difficult to use. More recently developed atypical injectables, including paliperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole, while expensive, may be cost effective in reducing hospitalization and may therefore offer advantage to oral compounds.

Standard dosage: Varies by compound

Contraindications: Inability to tolerate oral formulation

Main drug interactions: Varies by compound

Special points: For discussion of practical issues such as specific indications, approved injection sites, needle gauge, injection volume and intervals, see [48].

Cost-effectiveness: Strong support for cost-effectiveness of based upon reduced hospitalization [49, 50]

Class of drugs: Clozapine

The atypical clinical effects of clozapine including superior efficacy and reduced risk for tardive dyskinesia were demonstrated post-hoc in the late 1980’s. Its use is complicated by the potential for inducing fatal agranulocytosis, which necessitates weekly blood monitoring. It may also be tolerated poorly due to side effects such as orthostatic hypotension or weight gain, and at high doses is associated with increased seizure risk. Nevertheless, its superior efficacy is supported by both large scale effectiveness studies such as CATIE [42] and EUFEST [43] and by meta-analyses of RCTs [18], suggesting that more widespread use is probably warranted [37]. Furthermore, clozapine may decrease risk for suicide over and above antipsychotic effects [51]. Suicide remains a major cause of excess mortality in schizophrenia. Along with effects on dopaminergic, serotonergic and cholinergic receptors, clozapine modulates NMDAR function [52], which may underlie its differential efficacy.

Standard dosage: 150–600 mg (maximum FDA dose = 900 mg)

Contraindications: History of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia or spontaneous myeloproliferative disorder. Coma or severe CNS depression. Seizure history.

Main drug interactions: CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4

Special points: Dose-related increased risk for seizures. [53]. Has anti-suicide effects over and above

Cost-effectiveness: Cost of monitoring more than offset by cost of reduced hospitalization and increase in life expectancy [41]

Interventional procedures

Potential interventional approaches include behavioral interventions such as cognitive remediation (CR) or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), or neuromodulatory treatment such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). For subjects with anti-NMDAR antibodies, specific immunosuppressive therapies may be effective.

Cognitive remediation may produce moderate improvements in cognitive function [54]. However, interventions remain difficult to implement, require high levels of patient adherence, and standard approaches have not yet been developed.

Sensory deficits may contribute significantly to social and functional impairments [55–57]. Therapies aimed at reversing these deficits, such as music therapy [58] or auditory training [59, 60], may have a significant impact on negative symptoms, depression and social function.

Reading impairments may contribute disproportionately to impaired occupational outcome [61, 62] and may respond to specific behavioral intervention.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) currently under investigational use for treatment of negative symptoms [63]

Cognitive behavior therapy for relapse prevention [64] and positive/negative symptom treatment [65]. May be effective even in cognitively impaired, low functioning patients [65].

TMS has shown effects in some studies [66], but use has been inconsistent over studies and may be relatively time limited (<1 mo) [67]

Cathodal tDCS over left auditory cortex has recently been reported to be highly effective for persistent auditory verbal hallucinations, with effects persisting for >3 mo [68]

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be beneficial for catatonia and some positive symptoms paranoid delusions [69]

Anti-NMDA receptor antibodies may be observed in a minority of patients [70]. In such cases, however, first-line immunotherapeutic interventions such as plasmophoresis or anti-IgG antibodies [71] should be considered.

Emerging treatment

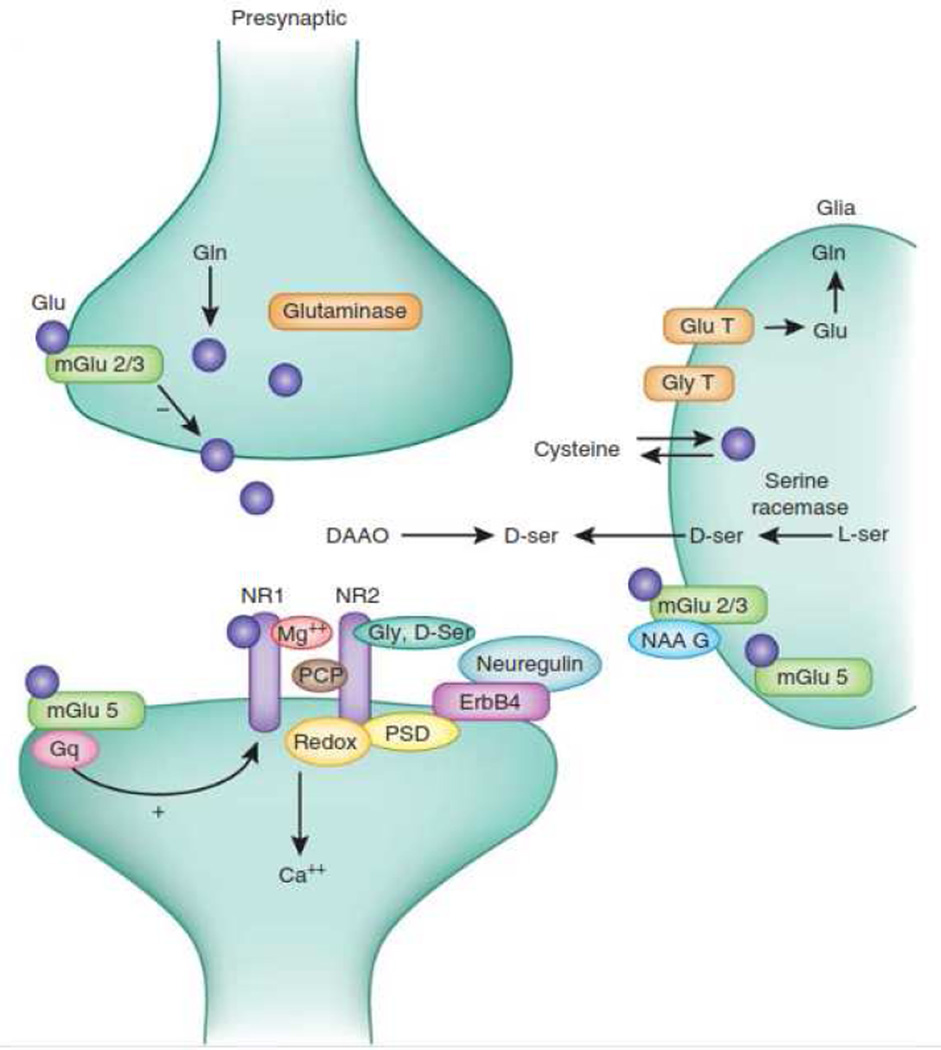

All current medications for schizophrenia are based upon dopaminergic models. More recent drug development activities, however, are based upon glutamatergic models. Glutamate models derive from the ability of NMDAR antagonists such as phencyclidine (PCP) or ketamine to induce symptoms that closely resemble schizophrenia [72] (Figure 1). NMDAR are modulated by the amino acids glycine and D-serine which are present endogenously in the brain, and by glutathione which binds to a redox-sensitive site [73–75]. Other targets, such as nitric oxide synthesis or inflammation may either cause or be “downstream” of NMDR dyfunction. Several compounds based upon glutamatergic theories are currently in late-stage clinical development. Hormonal and anti-inflammatory approaches are also under investigation.

Glycine, D-serine and sarcosine are natural compounds that have been used investigationally in schizophrenia [74, 76, 77]

Synaptic glycine levels are modulated by Glycine Type 1 (GlyT1) transporters. Glycine reuptake inhibitors increase synaptic glycine levels by blocking GlyT1 and are currently in phase III clinical development [78] (Table 2)

D-Serine is metabolized by D-amino acid oxidase (DAAO). Benzoate, a compound that inhibits D-amino acid oxidase, is reported to be therapeutically beneficial [79]

Other glutamate targets include metabotropic type 2; 3 receptors that are expressed presynaptically, and type 5 receptors that are coexpressed postsynaptically with NMDAR [80–82] (Figure 1, Table 2).

α7 nicotinic receptors are linked to schizophrenia [83, 84] and modulate NMDAR function [85]. α7 agonists are presently in phase III clinical trials (Table 2).

Redox dysregulation may be treated with the glutathione precursor N-acetylcysteine (NAC) [86]

Reported effectiveness of nitroprusside [87] supports potential involvement of nitric oxide system [88, 89].

Use of oxytocin is also supported by double-blind, placebo-controlled studies [90]

Anti-inflammatory medications (e.g. aspirin, celecoxib) may be effective [91]

Omega-3 fatty acids are often considered [92], but use is not supported by present evidence [93]

Deficit in non-rapid eye movement (stage3/4) sleep may contribute to cognitive dysfunction, and may respond to GABAB agonists (e.g. oxybutyrate) [94]

Figure 1.

Schematic model of the glutamate synapse, showing binding sites for glycine (Gly) and D-serine (D-ser), along with Type 1 glycine transporters (Gly T) that represent a target for drug development. Other targets include metabotropic type 2/3 (mGlu 2/3) or type 5 (mGlu 5), or D-amino acid oxidase (DAAO). (Used with permission from Moghaddam, B. and D. Javitt, From revolution to evolution: the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia and its implication for treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2012. 37(1): p. 4–15.)

Table 2.

Targets and compounds currently in clinical development

| Compound | Mechanism of action |

Example | Target symptoms | Development stage/status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine site agonist | Stimulates NMDAR at glycine; D-serine binding site | Glycine; D-serine | Persistent negative symptoms; neurodegeneration in early psychosis | Phase II/ ongoing studies |

| Glycine reuptake inhibitor | Increases synaptic glycine levels by blocking Glycine Type 1 Transporters | Bitopertin | Suboptimally controlled symptoms; neurodegeneration in early psychosis | Phase III; No significant effects on negative symptoms; ongoing studies for suboptimal response |

| Metabotropic type 2; 3 receptor agonist | Inhibits presynaptic glutamate release by stimulating presynaptic mGluR | Pomeglumetad | Early psychosis; neurodegeneration | Phase II/III; No significant effects on total symptoms; potential effects in early psychosis |

| Metabotropic type 5 receptor agonist | Potentiates postsynaptic NMDAR function | VU0092273 [95] | Negative symptoms; cognition | Preclinical |

| Alpha7 nicotinic agonist | Stimulates presynaptic glutamate release | EV-6124 | Negative symptoms; cognition | Phase III for Cognitive Impairment Associated with schizophrenia |

Opinion statement.

Current treatments for schizophrenia function by blocking neurotransmission at dopamine D2 receptors. These compounds have proven highly effective for treatment of schizophrenia and especially for management of positive symptoms. A range of compounds and formulations are presently available which permit tailoring of side effects to optimize treatment for individual subjects. Nevertheless, many patients suffer from persistent negative symptoms and neurocognitive deficits that contribute to persistent psychosocial impairments and long term disability. At present, there are no approved pharmacological treatments for either negative symptoms or neurocognitive dysfunction. Instead, various behavioral approaches such as diet, exercise and cognitive remediation may be needed to help optimize cognitive function and mitigate symptoms. Furthermore, neuromodulation approaches, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are beginning to be employed both to minimize symptoms and to augment cognitive retraining approaches. At present, encouraging effects of tDCS on persistent auditory hallucinations have been reported and, if confirmed, may open the way for more widespread use of non-pharmacological treatments. At present, phase III studies remain ongoing for α7 nicotinic agonists in treatment of cognitive impairments and glycine reuptake inhibitors for suboptimal treatment response. Furthermore, preclinical studies suggest that glutamate-based treatment approaches may be effective if applied early in the illness. Future studies are needed to determine whether this will lead to effective approaches to halt illness progression for individuals at high clinical risk for schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Daniel C. Javitt reports consultancy work for Sunovion, BMS, Eli Lilly, Tadeda, Omeros, SKBP, and Otsuka. He declares board membership at Promentis and employment from Glytech. He has received grants from Pfizer, Roche and Jazz, outside of the submitted work, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Javitt has received payment for lectures from Pfizer; holds patents with and receives royalties from Glytech, Inc; and has been awarded payment for development of educational presentations from Consensus Medical Communications, Vindico Medical Communications, Clearview Healthcare, AMCP, Rockpointe Communication, and Envivo. He owns stock/stock options in Promentis and has been afforded unrelated meeting expenses from Lundbeck.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the author.

References

Recently published papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

* Of importance

** Of major importance

- 1.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):83–88. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildgust HJ, Beary M. Are there modifiable risk factors which will reduce the excess mortality in schizophrenia? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4) Suppl:37–50. doi: 10.1177/1359786810384639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zschucke E, Gaudlitz K, Strohle A. Exercise and physical activity in mental disorders: clinical and experimental evidence. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013;46(Suppl 1):S12–S21. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.S.S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pajonk FG, et al. Hippocampal plasticity in response to exercise in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):133–143. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roffman JL, et al. Genetic variation throughout the folate metabolic pathway influences negative symptom severity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):330–338. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vares M, et al. Association between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism and age of onset in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(2):610–618. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srisawat U, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) 677C/T polymorphism is associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Winkel R, et al. MTHFR and risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;121(1–3):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kevere L, et al. Elevated serum levels of homocysteine as an early prognostic factor of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:373261. doi: 10.1155/2012/373261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayesa-Arriola R, et al. Homocysteine and cognition in first-episode psychosis patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(7):557–564. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich-Muszalska A, et al. The oxidative stress may be induced by the elevated homocysteine in schizophrenic patients. Neurochem Res. 2012;37(5):1057–1062. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0707-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolton AD, Phillips MA, Constantine-Paton M. Homocysteine reduces NMDAR desensitization and differentially modulates peak amplitude of NMDAR currents, depending on GluN2 subunit composition. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110(7):1567–1582. doi: 10.1152/jn.00809.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gysin R, et al. Genetic dysregulation of glutathione synthesis predicts alteration of plasma thiol redox status in schizophrenia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(7):2003–2010. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roffman JL, et al. Randomized multicenter investigation of folate plus vitamin B12 supplementation in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):481–489. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill M, et al. Folate supplementation in schizophrenia: a possible role for MTHFR genotype. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kern RS, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):214–220. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keefe RS, et al. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2–3):283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leucht S, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zipursky RB, Menezes NM, Streiner DL. Risk of symptom recurrence with medication discontinuation in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emsley R, et al. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leucht S, et al. Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD008016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008016.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Comprehensive comparison of antipsychotic use in maintenance treatment

- 22.Zhang JP, Malhotra AK. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotics: recent progress and methodological issues. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(2):183–191. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.736964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballon J, Stroup TS. Polypharmacy for schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(2):208–213. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835d9efb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischhacker WW, Uchida H. Critical review of antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dold M, et al. Benzodiazepine augmentation of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1023–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kishi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor augmentation therapy for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(11):1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llorca PM, et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):340. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishimoto T, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan G, Casoy J, Zummo J. Impact of long-acting injectable antipsychotics on medication adherence and clinical, functional, and economic outcomes of schizophrenia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:1171–1180. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S53795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emsley R, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in early psychosis: a literature review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7(3):247–254. doi: 10.1111/eip.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leucht C, et al. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia--a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirson NY, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):568–575. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r08167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs. oral antipsychotic medications in the prevention of relapse provides a case study in comparative effectiveness research in psychiatry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8) Suppl:S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kranzler HN, Cohen SD. Psychopharmacologic treatment of psychosis in children and adolescents: efficacy and management. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;22(4):727–744. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar A, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for psychosis in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD009582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009582.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wenthur CJ, Lindsley CW. Classics in chemical neuroscience: clozapine. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4(7):1018–1025. doi: 10.1021/cn400121z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meltzer HY. Clozapine: balancing safety with superior antipsychotic efficacy. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2012;6(3):134–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manuel JI, et al. Factors associated with initiation on clozapine and on other antipsychotics among Medicaid enrollees. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(11):1146–1149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Citrome L. Cariprazine in schizophrenia: clinical efficacy, tolerability, and place in therapy. Adv Ther. 2013;30(2):114–126. doi: 10.1007/s12325-013-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newman-Tancredi A. The importance of 5-HT1A receptor agonism in antipsychotic drug action: rationale and perspectives. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11(7):802–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meltzer HY. Update on typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:393–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050911-161504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Comprehensive discussion of neurochemical basis of typical vs. atypical antipsychotics

- 42.Lieberman JA, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahn RS, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehman AF, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):193–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreyenbuhl J, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):94–103. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravyn D, et al. CYP450 pharmacogenetic treatment strategies for antipsychotics: a review of the evidence. Schizophr Res. 2013;149(1–3):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perera V, et al. Considering CYP1A2 phenotype and genotype for optimizing the dose of olanzapine in the management of schizophrenia. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(9):1115–1137. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.795540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Citrome L. New second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(7):767–783. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.811984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bera R, et al. Impact on healthcare resource usage and costs among Medicaid-insured schizophrenia patients after initiation of treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2013;16(4):522–528. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.771641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Achilla E, McCrone P. The cost effectiveness of long-acting/extended-release antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(2):95–106. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meltzer HY, et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):82–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Javitt DC, et al. Inhibition of system A-mediated glycine transport in cortical synaptosomes by therapeutic concentrations of clozapine: implications for mechanisms of action. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(3):275–287. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Remington G, et al. Clozapine and therapeutic drug monitoring: is there sufficient evidence for an upper threshold? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;225(3):505–518. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keefe RS, Harvey PD. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;(213):11–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25758-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gold R, et al. Auditory emotion recognition impairments in schizophrenia: relationship to acoustic features and cognition. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):424–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11081230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Friedman T, et al. Differential relationships of mismatch negativity and visual p1 deficits to premorbid characteristics and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(6):521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Demonstration of the critical role for auditory dysfunction in functional outcome in schizophrenia

- 57.Yang L, et al. Schizophrenia, culture and neuropsychology: sensory deficits, language impairments and social functioning in Chinese-speaking schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. 2012;42(7):1485–1494. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mossler K, et al. Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD004025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher M, et al. Using neuroplasticity-based auditory training to improve verbal memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):805–811. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08050757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biagianti B, Vinogradov S. Computerized cognitive training targeting brain plasticity in schizophrenia. Prog Brain Res. 2013;207:301–326. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63327-9.00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Revheim N, et al. Reading impairment and visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;87(1–3):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Revheim M, et al. Reading deficits in established and prodromal schizophrenia: further evidence for early visual and later auditory dysfunction in the course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. in revision. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prikryl R, Kucerova HP. Can repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation be considered effective treatment option for negative symptoms of schizophrenia? J ECT. 2013;29(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318270295f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olivares JM, et al. Definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grant PM, et al. Randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of cognitive therapy for low-functioning patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):121–127. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aleman A, Sommer IE, Kahn RS. Efficacy of slow repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of resistant auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(3):416–421. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Slotema CW, et al. Meta-analysis of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of auditory verbal hallucinations: update and effects after one month. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1–3):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brunelin J, et al. Examining transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) as a treatment for hallucinations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(7):719–724. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Initial controlled study of tDCS for treatment of persistent auditory hallucinations

- 69.Zervas IM, Theleritis C, Soldatos CR. Using ECT in schizophrenia: a review from a clinical perspective. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(2):96–105. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.564653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steiner J, et al. Increased prevalence of diverse N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor antibodies in patients with an initial diagnosis of schizophrenia: specific relevance of IgG NR1a antibodies for distinction from N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):271–278. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Discussion of potential role of autoantibodies to NMDA receptors in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia

- 71.Titulaer MJ, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(10):1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moghaddam B, Javitt D. From revolution to evolution: the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia and its implication for treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):4–15. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Recent update on glutamatergic models of schizophrenia

- 74.Kantrowitz J, Javitt DC. Glutamatergic transmission in schizophrenia: from basic research to clinical practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):96–102. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Javitt DC, et al. Has an angel shown the way? Etiological and therapeutic implications of the PCP/NMDA model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(5):958–966. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kantrowitz JT, et al. High dose D-serine in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;121(1–3):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nunes EA, et al. D-serine and schizophrenia: an update. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(7):801–812. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Javitt DC. Glycine transport inhibitors for the treatment of schizophrenia: symptom and disease modification. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12(4):468–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lane HY, et al. Add-on Treatment of Benzoate for Schizophrenia: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of d-Amino Acid Oxidase Inhibitor. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1267–1275. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Noetzel MJ, Jones CK, Conn PJ. Emerging approaches for treatment of schizophrenia: modulation of glutamatergic signaling. Discov Med. 2012;14(78):335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matosin N, Newell KA. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the pathology and treatment of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(3):256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vinson PN, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets for schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(3):1461–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Freedman R. alpha7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists for Cognitive Enhancement in Schizophrenia. Annu Rev Med. 2013 doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-092112-142937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Comprehensive review of literature supporting use of α7 nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia

- 84.Young JW, Geyer MA. Evaluating the role of the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86(8):1122–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin H, et al. Cortical synaptic NMDA receptor deficits in alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene deletion models: Implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;63C:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kulak A, et al. Redox dysregulation in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: insights from animal models. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(12):1428–1443. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hallak JE, et al. Rapid improvement of acute schizophrenia symptoms after intravenous sodium nitroprusside: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):668–676. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maia-de-Oliveira JP, et al. Nitric oxide plasma/serum levels in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34(Suppl 2):S149–S155. doi: 10.1016/j.rbp.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coyle JT. Nitric oxide and symptom reduction in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):664–665. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Macdonald K, Feifel D. Oxytocin in schizophrenia: a review of evidence for its therapeutic effects. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2012;24(3):130–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Muller N, Myint AM, Schwarz MJ. Immunological treatment options for schizophrenia. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(8):1606–1613. doi: 10.2174/138920112800784826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Torrey EF, Davis JM. Adjunct treatments for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: what to try when you are out of ideas. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2012;5(4):208–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fusar-Poli P, Berger G. Eicosapentaenoic acid interventions in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):179–185. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318248b7bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kantrowitz J, Citrome L, Javitt D. GABA(B) receptors, schizophrenia and sleep dysfunction: a review of the relationship and its potential clinical and therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(8):681–691. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923080-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rodriguez AL, et al. Discovery of novel allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 reveals chemical and functional diversity and in vivo activity in rat behavioral models of anxiolytic and antipsychotic activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78(6):1105–1123. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]