Abstract

Background

A number of studies have assessed the predictive effect of QRS-T angles in various populations since the last decade. The objective of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the prognostic value of spatial/frontal QRS-T angle on all-cause death and cardiac death.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched from their inception until June 5, 2014. Studies reporting the predictive effect of spatial/frontal QRS-T angle on all-cause/cardiac death in all populations were included. Relative risk (RR) was used as a measure of effect.

Results

Twenty-two studies enrolling 164,171 individuals were included. In the combined analysis in all populations, a wide spatial QRS-T angle was associated with an increase in all-cause death (maximum-adjusted RR: 1.40; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.32 to 1.48) and cardiac death (maximum-adjusted RR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.54 to 1.90), a wide frontal QRS-T angle also predicted a higher rate of all-cause death (maximum-adjusted RR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.54 to 1.90). Largely similar results were found using different methods of categorizing for QRS-T angles, and similar in subgroup populations such as general population, populations with suspected coronary heart disease or heart failure. Other stratified analyses and meta-analyses using unadjusted data also generated consistent findings.

Conclusions

Spatial QRS-T angle held promising prognostic value on all-cause death and cardiac death. Frontal QRS-T angle was also a promising predictor of all-cause death. Given the good predictive value of QRS-T angle, a combined stratification strategy in which QRS-T angle is of vital importance might be expected.

Introduction

As one of the most commonly used diagnostic technique, ECG is available in almost all hospitals and outpatient clinics. Numerous parameters could be easily obtained from the routine 12-lead ECG. Some of these parameters, such as QT interval and ST-segment depression, carry prognostic information for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1,2]. Recent attention has been paid to spatial and frontal QRS-T angles—two different forms of QRS-T angle. Spatial QRS-T angle is defined as the angle between QRS- and T-wave vectors in three-dimensional space, and frontal QRS-T angle is the projection of spatial QRS-T angle onto the frontal plane [3]. QRS-T angles reflect the deviations between ventricular depolarization and repolarization, and are postulated to have promising predictive value [4,5]. Since the last decade, the prognostic effects of spatial and frontal QRS-T angles have been extensively studied both in general population and particular subpopulations [3,5–25]. A large portion of these studies showed that a wide QRS-T angle predicted a poor prognosis [9,21], but inconsistent findings existed at the same time [7,8,11]. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to provide a clearer understanding of the impact of QRS-T angles on the risk of all-cause death and cardiac death.

Methods

Literature search

We sought to identify all the published studies evaluating the prognostic value of QRS-T angles on risk of all-cause death and cardiac death in all populations. From their inception until June 5, 2014, PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were systemically searched using the following search terms and key words: "QRS-T angle" OR "QRS/T angle" OR "QRS|T angle" OR "QRST angle" OR "QRSTA". Reference lists of the identified reports and relevant reviews were manually checked for potential studies not otherwise found. No restrictions on language, type of publication were imposed.

Study selection

After reviewing all titles and abstracts, we identified reports which were potentially relevant. Thereafter, these potentially eligible articles were further reviewed in full-text to check whether they met all of the following inclusion criteria: 1) divided spatial or frontal QRS-T angles into categorical groups and evaluated their prognostic value in hard endpoints, i.e. all-cause death or cardiac death; 2) the minimum duration of follow-up was 12 months; 3) the number of participants were at least 100; 4) reported relative risks (RRs) with 95% corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) or provided raw data necessary to calculate them. Studies fulfilled all these criteria above, regardless of the population types (both general population and other particular subpopulations, such as patients with suspected coronary heart disease [CHD]), were included in the meta-analysis.

Data collection and quality assessment

The primary endpoint was all-cause death and the secondary endpoint was cardiac death. All endpoints were defined by the investigators of each study. Study eligibility was assessed and data were extracted independently by three reviewers (XZ, QZ and LZ). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. By using a predesigned data abstraction form, the following information was recorded: the study name/first author, type of QRS-T angle, study population (general population or other particular subpopulations), year of publication, study period, number of participants, age, gender, duration of follow-up, mean QRS-T angle, and categories of QRS-T angle. Confounding factors for which were adjusted in each study were also recorded (S1 Table). Because the set of adjustments vary within studies, which were allowed in this meta-analysis, we extracted the maximum-adjusted RRs and their corresponding 95% CIs for each categorical comparison. Meanwhile, unadjusted RRs (and 95% CIs) or raw data used to calculate RRs were extracted. The quality of the included studies was assessed independently by two investigators (LZ and HJ) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale criteria [26].

Statistical analysis

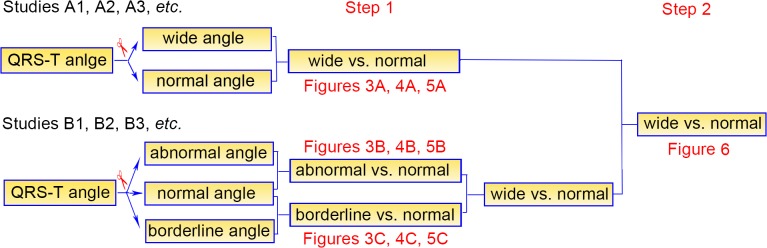

As the types of clinical presentation varied (the normal ranges of QRS-T angles varied accordingly), the cut-off points of both spatial and frontal QRS-T angles were different among these studies. As a rule, we directly employed the cut-offs defined by investigators in each individual study. A two-step analysis strategy was used in our study (Fig 1). First, in studies (A1, A2, A3, etc. in Fig 1) which one cutoff was set and thus QRS-T angles were divided into “wide angle” and “normal angle”, a meta-analysis of wide angles versus normal ones was conducted (step 1 in Fig 1); in studies (B1, B2, B3, etc. in Fig 1) which two cutoffs were set and QRS-T angles were segmented into three groups, i.e. normal, borderline and abnormal angles, we compared abnormal and borderline angles with normal angles respectively (step 1 in Fig 1). Second, data from abnormal and borderline angles were combined into wide angles in studies B1, B2, B3, etc., and then pooled together with data from studies A1, A2, A3, etc. (step 2 in Fig 1).

Fig 1. An overview of the 2-step analysis strategy in our study.

For all analyses, RR and its corresponding 95% CI were computed as a measure of effect. Fixed-effects models (Mantel-Haenszel method) were used to pool RR in each study unless otherwise stated [27]. The I 2 statistic was calculated to assess the consistency across studies, with 25% indicating low, 50% moderate, and 75% high degrees of heterogeneity [28]. Meanwhile, the χ2-based Q test was applied, a P>0.1 suggests significant heterogeneity [29]. In analyses with significant heterogeneity, the random-effects models (DerSimonian and Laird method) were used [30]. Publication bias was qualitatively addressed by visual inspection of the funnel plot asymmetry, as well as quantitatively assessed by Begg’s test [31]. Sensitivity analyses were carried out for all endpoints, by omitting one study at one time, to evaluate the consistency of our findings. In addition, subgroup analyses were performed by making stratifications of following factors: type of clinical presentation (general population, patients with suspected CHD, or patients with heart failure), number of participants (4000 or 2000 as cut-offs for spatial and frontal QRS-T angles respectively), and duration of follow-up (less than 5 years or more than 5 years). Meta-regression analyses were performed to estimate the interaction between prognosis (all-cause death and cardiac death) and these subgroup factors. All statistical analyses were conducted with the STATA version 11.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) software. The study was performed and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (S1 Checklist) [32].

Results

Eligible studies

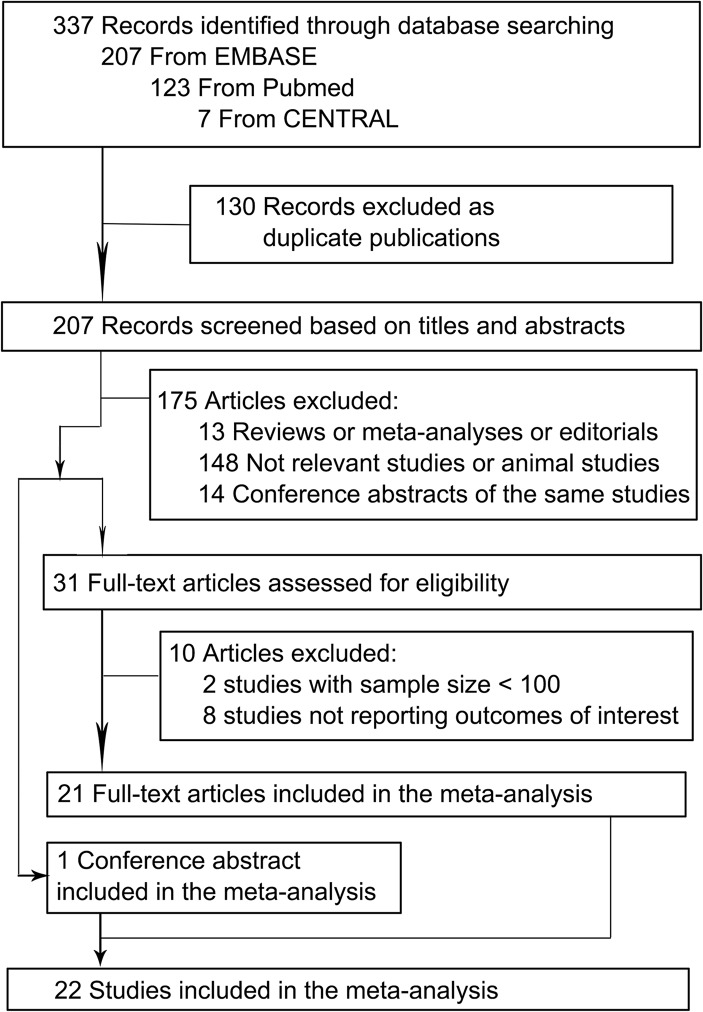

Fig 2 shows the flow diagram of this meta-analysis. Of the 337 potentially relevant reports initially retrieved from PubMed, EMBASE and CENTRAL, 22 studies—21 full-text articles [3,5–15,17–25] and 1 conference abstract [16]—satisfied our inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. Among the 22 studies, 11 studies only reported data on all-cause death [3,7,8,10,11,13,16,17,20,23,24], 3 studies only reported data on cardiac death [12,15,21] and 8 studies reported data on both endpoints [5,6,9,14,18,19,22,25]. Ten studies were conducted in general population without a particular disease [5,9,10,12,13,19–23], while the other 12 studies were carried out in particular subpopulations, such as patients with heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, or chronic dialysis [3,6–8,11,14–18,24,25].

Fig 2. Selection of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The period of the baseline data collection ranged from 1966 to 2011, and the duration of follow-up was between 1 and 30 years. The mean age ranged from 44 to 72 years, and the percentage of men from 0 to 100. Overall, data were available from 164171 individuals in 22 studies. In the analyses of adjusted studies, we employed data after adjustment for maximum confounders, which were listed in S1 Table. The quality of the studies was acceptable in all studies. The detailed scores of each study assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale were presented in S1 Table.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author/Study/Ref | QRS-T angle type | Population of study | Publishing Year | Period of data collection | Number of subjects | Men (%) | Age (years) | Follow-up (years) | Mean QRS-T angle (°) | Categories of QRS-T angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kardys et al. [22] | Spatial | Population-based | 2003 | 1990–1993 | 6134 | 40.4 | 69.2±8.7 | 6.7 | NA | ≤105°, 105–135°, ≥135° |

| de Torbal et al. [11] | Spatial | Patients with acute ischemic chest pain | 2004 | 1992–1994 | 2261 | 55 | NA | 6.3 | NA | <105°, 105–135°, >135° |

| Yamazaki et al. [21] | Spatial | A clinical population | 2005 | 1987–2000 | 46573 | 90 | 56.8±14.7 | 6 | 43.7 | ≤50°, 50–100°, ≥100° |

| Rautaharju et al. (CHS) [9] | Spatial | Over 65 years old | 2006 | 1989–1994 | 4912 | 39.5 | 72.6±5.5 | 9.1 | 74±33.4 | <126°, ≥126° in men; <107°, ≥107° in women |

| Rautaharju et al. (WHI) [12] | Spatial | Postmenopausal women | 2006 | 1992–2007 | 38283 | 0 | 62.1±6.8 | 6.2 | NA | ≤56°, 57–96°; ≥97° |

| Zhang et al. (ARIC) [10] | Frontal | Population-based | 2007 | 1987–1989 | 13873 | 42.3 | 54.4±5.7 | 14 | 23.9±24.0 | ≤32°, 32–73°, ≥73° in men; ≤31°, 31–67°, ≥67° in women |

| Spatial | 67.2±28.0 | ≤93°, 93–123°, ≥123° in men; ≤77°, 77–110°, ≥110° | ||||||||

| Pavri et al. (DEFINITE) [17] | Frontal | NICM patients | 2008 | 1998–2002 | 455 | 71.2 | 58.2±12.9 | 2.5±1.2 | NA | <90°, >90° |

| Borleffs et al. [5] | Frontal | IHD patients with ICD therapy | 2009 | 1996- | 412 | 88 | 63±11 | 2±1.5 | NA | <90°, >90° |

| Spatial | <100°, >100° | |||||||||

| Lipton et al. [6] | Spatial | Known or suspected CAD who underwent DSE | 2009 | 1990–2003 | 2347 | 66 | 61±3 | 7±3.4 | NA | <105°, 105–135°, >135° |

| Rubulis et al. [15] | Spatial | SAP patients | 2010 | 1995–1997 | 187 | 74 | 58±10 | 8±1 | NA | <101°, ≥101° |

| Kentt et al. (FINCAVAS) [18] | Spatial | Patients undergoing a clinically indicated bicycle stress-test | 2011 | 2001–2007 | 1297 | 67 | 56±13 | 3.8±1 | NA | <72°, ≥72° |

| Aro et al. [4] | Frontal | Middle-aged | 2012 | 1966–1972 | 10713 | 52.2 | 43.9±8.4 | 30±11 | 20° | <90°, ≥100° |

| Lown et al. [7] | Frontal | ACS patients | 2012 | 2003 | 1843 | 61.9 | 70.1±13.1 | 2 | NA | ≤37°, 38–104°, ≥105° |

| Whang et al. (NHANES III) [19] | Frontal | Over 40 years old | 2012 | 1988–1994 | 7052 | 46.3 | NA | 14 | NA | ≤39°, 39–80°, ≥81° |

| Spatial | ≤90°, 90–120°, ≥121° | |||||||||

| de Bie et al. [14] | Spatial | Chronic dialysis patients | 2013 | 2002–2009 | 277 | 62.1 | 56.3±17.0 | 2.1±1.7 | 103.5±41.2 | <130°, ≥130° in men; <116°, ≥116° in women |

| Gotsman et al. [24] | Frontal | HF patients | 2013 | 2008- | 5038 | 51 | NA | 1.6 | NA | <65°, 65–124°, >124° |

| Vend et al. (MADIT II) [16] | Frontal | ICM patients | 2013 | NA | 1232 | NA | NA | 4 | NA | <90°, >90° |

| Strauss et al. [20] | Spatial | In and outpatients | 2013 | 2009–2010 | 18488 | 51.8 | NA | 1 | NA | <105°, ≥105° |

| Laukkanen et al. [23] | Spatial | Population-based | 2014 | 1984–1989 | 1951 | 100 | NA | 20 | NA | <67°, ≥67° |

| Raposeiras-Roubín et al. [25] | Frontal | AMI patients with depressed LVEF | 2014 | 2004–2010 | 467 | 75.4 | 70±12.5 | 3.9 | 95.9±57.3 | <90°, >90° |

| Selvaraj et al. [8] | Frontal | HFpEF patients | 2014 | 2008–2011 | 376 | 35 | 64±13 | 1 | 61±51 | ≤26°, 27–75°, ≥76° |

Abbreviations: ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; ARIC: the Atherosclerosis in Communities Study; CAD: coronary artery disease; CHS: the Cardiovascular Health Study; DEFINITE: the Defibrillators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation; DSE: dobutamine stress echocardiography; FINCAVAS: The Finnish Cardiovascular Study; HF: heart failure; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ICM: ischemic cardiomyopathy; IHD: ischemic heart disease; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MADIT II: the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II; NHANES III: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NICM: nonischemic cardiomyopathy; SAP: stable angina pectoris; WHI: The Women’s Health Initiative.

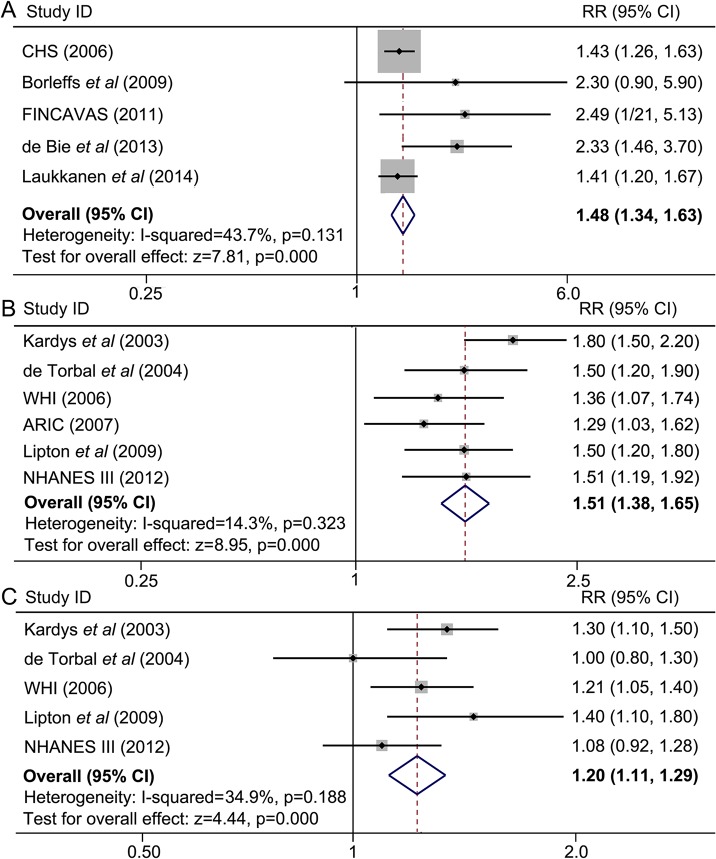

Spatial QRS-T angle and all-cause death

A total of 11 studies contributed to the analysis of the association between spatial QRS-T angle and all-cause death. Meta-analysis of studies A1, A2, A3, etc.(indicated in Fig 1) showed that a wide spatial QRS-T angle predicted a higher incidence of all-cause death (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.34–1.63). No significant but a modest degree of heterogeneity was observed (I 2 = 43.7%, P = 0.131) (Fig 3A). Pooled analyses in studies B1, B2, B3, etc. (indicated in Fig 1) demonstrated that an abnormal spatial QRS-T angle was associated with a significantly higher mortality compared with a normal angle (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.38–1.65) (Fig 3B). A weaker but still significant association was also found in borderline spatial QRS-T angles (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.11–1.29) (Fig 3C). There was no evidence of significant heterogeneity.

Fig 3. A wide spatial QRS-T angle is associated with a higher incidence of all-cause death.

Meta-analyses were from separated comparisons by two methods of categorizing. (A) Spatial QRS-T angles were divided into “wide angle” and “normal angle”, a meta-analysis of wide angles versus normal ones was conducted. (B) and (C) spatial QRS-T angles were segmented into three groups, i.e. normal, borderline and abnormal angles. (B) Results from comparison between abnormal and normal, (C) results from comparison between borderline and normal. ARIC: the Atherosclerosis in Communities Study; CHS: the Cardiovascular Health Study; CI: confidence interval; FINCAVAS: The Finnish Cardiovascular Study; NHANES III: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RR: relative risk; WHI: The Women’s Health Initiative.

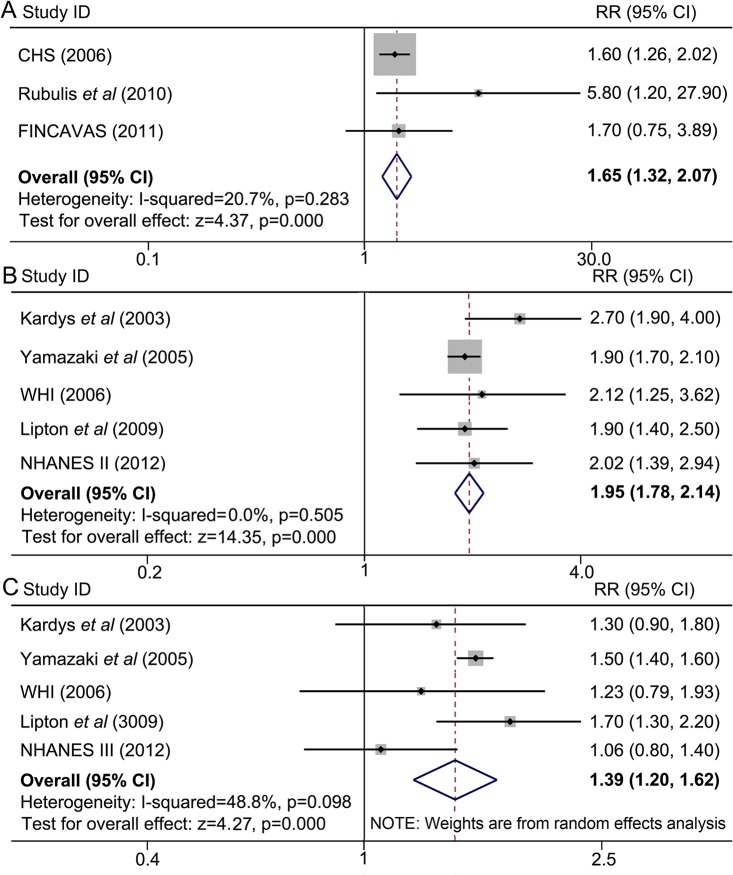

Spatial QRS-T angle and cardiac death

A total of 8 studies contributed to the analysis of the association between spatial QRS-T angle and cardiac death. Meta-analysis of studies A1, A2, A3, etc. (indicated in Fig 1) showed that a wide spatial QRS-T angle predicted a higher rate of cardiac mortality (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.35–2.07). No evidence of significant heterogeneity was detected (I 2 = 20.7%, P = 0.283) (Fig 4A). Pooled analyses in studies B1, B2, B3, etc. (indicated in Fig 1) demonstrated that an abnormal spatial QRS-T angle almost doubled the rate of cardiac mortality compared with a normal angle (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.78–2.14), without evidence of heterogeneity across these studies (I 2 = 0%, P = 0.505) (Fig 4B). Similarly, a borderline spatial QRS-T angle was also associated with a higher cardiac mortality (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.20–1.62), with a modest heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 48.8%, P = 0.098) (Fig 4C).

Fig 4. A wide spatial QRS-T angle is associated with a higher incidence of cardiac death.

Meta-analyses were from separated comparisons by two methods of categorizing. (A) Spatial QRS-T angles were divided into “wide angle” and “normal angle”, a meta-analysis of wide angles versus normal ones was conducted. (B) and (C) spatial QRS-T angles were segmented into three groups, i.e. normal, borderline and abnormal angles. (B) Results from comparison between abnormal and normal, (C) results from comparison between borderline and normal. CHS: the Cardiovascular Health Study; CI: confidence interval; FINCAVAS: The Finnish Cardiovascular Study; NHANES III: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RR: relative risk; WHI: The Women’s Health Initiative.

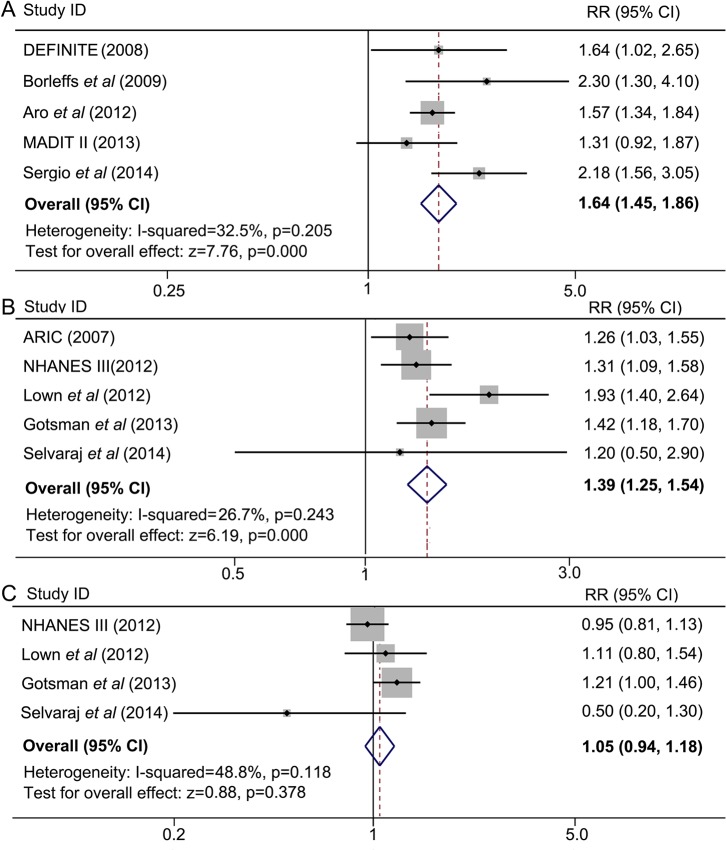

Frontal QRS-T angle and all-cause death

A total of 10 studies contributed to the analyses of the association between frontal QRS-T angle and all-cause death. Meta-analysis in studies A1, A2, A3, etc. (indicated in Fig 1) showed that a wide frontal QRS-T angle was associated with a significantly higher incidence of all-cause death, the pooled maximum-adjusted RR was 1.64 and the corresponding 95% CI was 1.45 to 1.86. No evidence of significant heterogeneity was detected (I 2 = 32.5%, P = 0.205) (Fig 5A). Similar to spatial QRS-T angle, the pooled maximum-adjusted RR for all-cause death was significantly higher in participants with abnormal frontal QRS-T angles than those with normal ones (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.25–1.54) (Fig 5B). However, no significant difference was observed between the borderline group and the normal group (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.94–1.18) (Fig 5C). No significant heterogeneity was found across these studies.

Fig 5. A wide frontal QRS-T angle is associated with a higher incidence of all-cause death.

Meta-analyses were from separated comparisons by two methods of categorizing. (A) Frontal QRS-T angles were divided into “wide angle” and “normal angle”, a meta-analysis of wide angles versus normal ones was conducted. (B) and (C) frontal QRS-T angles were segmented into three groups, i.e. normal, borderline and abnormal angles. (B) Results from comparison between abnormal and normal, (C) results from comparison between borderline and normal. ARIC: the Atherosclerosis in Communities Study; CI: confidence interval; DEFINITE: the Defibrillators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation; MADIT II: the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II; NHANES III: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RR: relative risk.

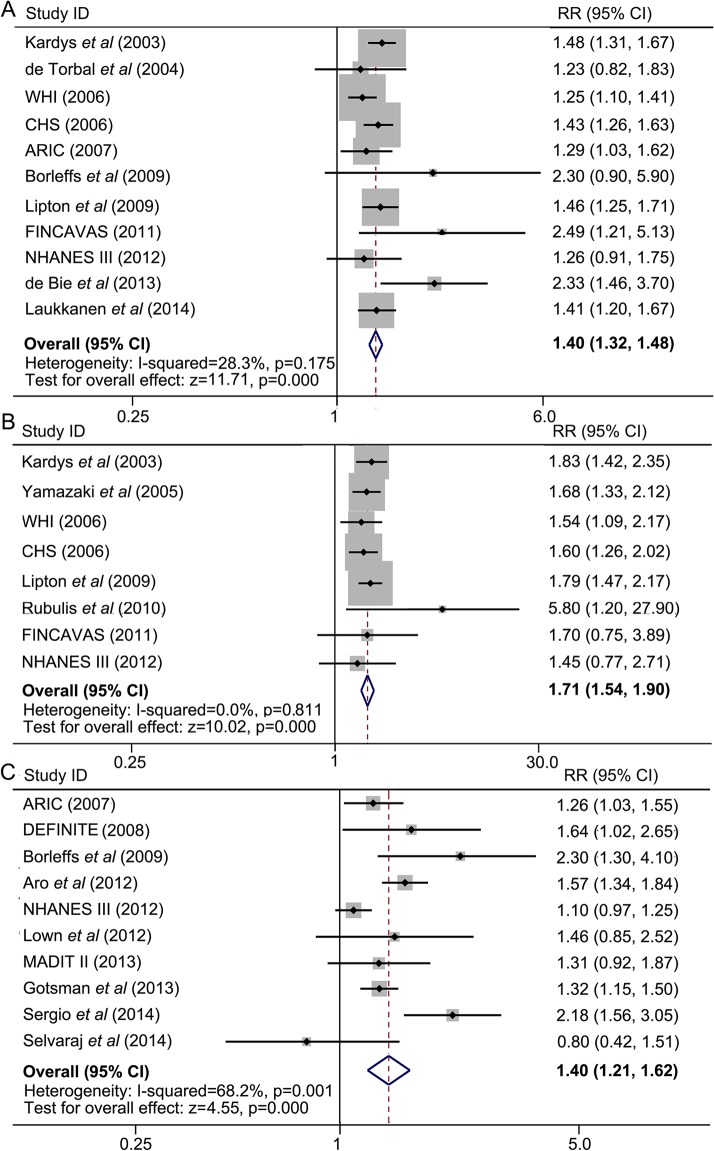

Combined analyses

In step-2 analysis, we pooled together data from all studies as comparisons of wide QRS-T angles with normal angles (Fig 1). Maximum-adjusted results from 11 studies on spatial QRS-T angle and all-cause death were pooled together, and a significant positive correlation was found between a wide spatial QRS-T angle and a higher incidence of mortality (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.32–1.48). No significant heterogeneity was found (I 2 = 28.3%, P = 0.175) (Fig 6A). Similarly, we pooled together maximum-adjusted data from 8 studies which reported spatial QRS-T angle and cardiac death. We found that wide spatial QRS-T angles significantly increased the rate of cardiac death, with a maximum-adjusted RR of 1.71 and corresponding 95% CI of 1.54 to 1.90. There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 0%, P = 0.811) (Fig 6B).

Fig 6. Combined analyses show that a wide spatial QRS-T angle predicts a higher incidence of all-cause death (A) and cardiac death (B), a wide frontal QRS-T angle is associated with a higher rate of all-cause death (C).

ARIC: the Atherosclerosis in Communities Study; CHS: the Cardiovascular Health Study; CI: confidence interval; DEFINITE: the Defibrillators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation; FINCAVAS: The Finnish Cardiovascular Study; MADIT II: the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II; NHANES III: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; RR: relative risk; WHI: The Women’s Health Initiative.

After pooling together all the 10 studies which reported frontal QRS-T angle and all-cause death, we found a significantly increased rate of mortality in people with wide frontal QRS-T angles (maximum-adjusted RR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.21–1.62). However, a significant heterogeneity was also found across these studies (I 2 = 68.2%, P = 0.001) (Fig 6C). To explore the origin of heterogeneity, we carried out sensitivity analysis and stratified subgroup analyses, which would be presented in the subsequent section.

Publication bias

With respect to all endpoints, no evidence of publication bias was found by using Begg’s test and visually inspecting the funnel plot asymmetry. As the number of studies included in part of the comparisons was limited, the qualitative evaluation by visual inspection in these analyses did not provide convincing results and the quantitative assessment by Begg’s test was used.

Stratified and sensitivity analyses

The overall association for spatial/frontal QRS-T angles and incidence of all-cause/cardiac death remained largely consistent when these studies were stratified by several characteristics of the studies, such as the type of clinical presentation, the number of participants, and the duration of follow-up (Table 2). For instance, when comparing a wide spatial QRS-T angle with a normal one, the combined RR of all-cause death was 1.37 (95% CI = 1.29–1.46) in general population and 1.47 (95% CI = 1.28–1.65) in patients with suspected CHD. Similarly for frontal QRS-T angle, the RR was 1.29 (95%CI = 1.03–1.62) in general population, 1.74 (95%CI = 1.41–2.14) in patients with suspected CHD, and 1.51 (95%CI = 1.18–1.94) in patients with heart failure. No significant interaction was found in most subgroup analyses except that a quantitative but not qualitative interaction was observed in analysis stratified by duration of follow-up when investigating spatial QRS-T angle and all-cause death (P value of interaction was less than 0.01). However the interaction did not result in a significant heterogeneity in the overall analysis (I 2 = 28.3%, P = 0.175). Notably, the total number of patients in all three studies with length of follow-up less than 5 years was 1986, which was very small, leading to wide-range-covering confidence intervals. No evidence of heterogeneity was detected for stratified analyses of spatial QRS-T angle, while high level of heterogeneity was found in several stratified analyses of frontal QRS-T angle.

Table 2. Stratified analyses in subgroups.

| Type of meta-analyses | No. of studies | Model | RR (95% CI) | I 2 (%) | P_hetero | P_Begg | P_int |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial QRS-T angle predicts all-cause death (wide angle versus normal one) | |||||||

| Type of clinical presentation | |||||||

| General population | 6 | Fixed | 1.37 (1.29–1.46) | 0 | 0.44 | 0.452 | 0.197 |

| Suspected CHD | 4 | Fixed | 1.47 (1.28–1.65) | 19.3 | 0.293 | 0.734 | |

| No. of participants | |||||||

| >4000 | 5 | Fixed | 1.37 (1.28–1.46) | 14.8 | 0.32 | 0.806 | 0.103 |

| <4000 | 6 | Fixed | 1.48 (1.33–1.64) | 35.2 | 0.173 | 0.707 | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||||

| >5 years | 8 | Fixed | 1.38 (1.31–1.46) | 0 | 0.583 | 0.266 | 0.000 |

| <5 years | 3 | Fixed | 2.36 (1.65–2.39) | 0 | 0.987 | 1 | |

| Spatial QRS-T angle predicts cardiac death (wide angle versus normal one) | |||||||

| Type of clinical presentation | |||||||

| General population | 5 | Fixed | 1.66 (1.47–1.88) | 0 | 0.909 | 0.462 | 0.319 |

| Suspected CHD | 3 | Fixed | 1.81 (1.50–2.19) | 6.6 | 0.343 | 0.296 | |

| No. of participants | |||||||

| >4000 | 5 | Fixed | 1.66 (1.47–1.88) | 0 | 0.909 | 0.462 | 0.319 |

| <4000 | 3 | Fixed | 1.81 (1.50–2.19) | 6.6 | 0.343 | 0.296 | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||||

| >5 years | 7 | Fixed | 1.71 (1.54–1.90) | 0 | 0.714 | 1 | 0.954 |

| <5 years | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Frontal QRS-T angle predicts all-cause death (wide angle versus normal one) | |||||||

| Type of clinical presentation | |||||||

| General population | 3 | Random | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) | 83.1 | 0.003 | 1 | |

| Suspected CHD | 4 | Fixed | 1.74 (1.41–2.14) | 45.4 | 0.139 | 1 | |

| Heart failure | 6 | Random | 1.51 (1.18–1.94) | 64.2 | 0.016 | 1 | |

| No. of participants | |||||||

| >2000 | 4 | Random | 1.30 (1.11–1.51) | 75.2 | 0.007 | 0.734 | 0.432 |

| <2000 | 6 | Random | 1.57 (1.19–2.08) | 53.2 | 0.06 | 0.454 | |

| Duration of follow-up | |||||||

| >5 years | 3 | Random | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) | 83 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.518 |

| <5 years | 7 | Random | 1.51 (1.21–1.88) | 57.1 | 0.03 | 1 | |

P_hetero: P value of heterogeneity across studies; P_Begg: P value from Begg’s test; P_int: P value of interaction in subgroups. CI: confidence intervals; RR: relative risks.

When comparing a wide QRS-T angle with a normal one, notably for both spatial and frontal QRS-T angles, the RRs tended to be lower in participants from general population than those in patients with a particular disease, such as suspected CHD and heart failure (Table 2). Similarly, in studies with a larger number of participants and a longer duration of follow-up, the RRs were smaller.

Sensitivity analyses in both overall analyses and stratified analyses by omitting one study at a time showed that none of the studies substantially changed the direction of the pooled RRs. The significant heterogeneity detected in stratified analyses of frontal QRS-T angle, however, did become much smaller or even non-significant when certain individual study was omitted. For instance, in analysis of studies with number of participants less than 2000, when the study of Selvaraj et al was omitted, the I 2 and P value for Begg’s test changed from 53.2 and 0.06 to 27.8 and 0.24 respectively, however the direction of RR remained consistent.

Meta-analyses of unadjusted data

We pooled data not adjusted for any confounding factors at the same time. The results were broadly similar with those from maximum-adjusted data, while there were discrepancies in amplitudes (S2 Table).

Discussion

In our meta-analysis, a wide spatial/frontal QRS-T angle was strongly associated with a higher incidence of all-cause/cardiac death in all populations, including general population, patients with suspected CHD and patients with heart failure. Although precisely quantitative conclusions of the prognostic value of QRS-T angles might not be addressed due to the limitations in our study, a qualitative result has been defined.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis conducted on QRS-T angles. QRS-T angles have been defined and studied for several decades, but intensive publications on prognostic information of QRS-T angles have not arisen until the last decade. Spatial QRS-T angle was noted earlier than frontal QRS-T angle. Spatial QRS-T angle reflects both the ventricular repolarization and depolarization vectors and thus has been considered as a potentially important ECG parameter with predictive value of the prognosis, because several variables on either repolarization or depolarization have been shown to predict cardiac morbidity and mortality [1,2,33]. Indeed in 2003, Kardys and colleagues reported that spatial QRS-T angle was a strong and independent predictor of cardiac death in an elderly population, and even stronger than any classical cardiovascular risk factors or known risk ECG variables [22]. Subsequently, a series of studies were conducted in various populations, with different number of participants and length of follow-up. Most of these studies yielded largely consistent results, although heterogeneity existed in the definitions of cut-offs and methods of categorizing. Because spatial QRS-T angle is not readily available in ECG machine currently in use, and is not familiar to most physicians, researchers begin to investigate frontal QRS-T angle, the reflection of spatial QRS-T angle on frontal plane, which is simpler to calculate. We believe that with the rapid development of automated ECG machine, the acquisition of spatial QRS-T angle would no longer puzzle physicians. It’s the good-or-bad (specificity and sensitivity) of the predictor, but not the small difference of availability, that should be considered most by clinicians once the clinical value of QRS-T angle is documented.

The population heterogeneity of these individual studies made stratified analyses in subgroup populations possible. In our study, we found that a wide QRS-T angle predicted a poor prognosis in general population, subpopulation with suspected CHD and subpopulation with heart failure. Notably, a more remarkable RR was detected in both subpopulations than in general population for both spatial and frontal QRS-T angles. Wide QRS-T angles might be associated with myocardial structure abnormity and electrophysiology alterations, and are always seen in patients with ischemia, pacing, cardiac hypertrophy and other nonischemic cardiomyopathy [17]. Indeed, subgroup populations with suspected CHD or heart failure in our study tended to have a wider QRS-T angle, while in general population, a narrower QRS-T angle was observed. Thus, a further increase of QRS-T angle on the basis of a “normal” angle which is actually wide in the subpopulations might generate a higher risk of poor prognosis than those in general population. Other stratified analyses categorized by the number of participants and the duration of follow-up were also performed. Studies with a larger number of individuals and a longer duration of follow-up generated less remarkable, but still significant RRs than their opposite categories respectively. It is not a surprise as it’s generally believed that data from studies with more participants and longer follow-ups are more credible and convincing, also in our study, more conservative.

The prognostic effect of QRS-T angles on all-cause/cardiac death might bring out their values on risk stratification, especially in patients with certain clinical presentation. In a recent meta-analysis aiming at seeking predictors of sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, only modest risk stratification was found in functional parameters, depolarization abnormalities, and repolarization abnormalities [33], in which QRS-T angle was not included due to lack of studies in that population [33]. Therefore, a comprehensive method of stratification combining numerous risk factors and other parameters, in which QRS-T angle might be vital, is necessary to well determine whether a patient is at higher risk. It has been commonly accepted that multivariate predictors significantly outperform individual factors in risk stratification [34]. This is because the nature of an end event is always multifactorial, but an individual predictor could only represent a single property (or pathophysiological pathway), rather than the overall pattern of performance [33,34]. Therefore, it is very difficult for an individual predictor to generate odd ratios high enough to confer meaningful prediction [34–36]. For instance, a risk score model comprising 5 clinical factors, each of which has a hazard ratio < 2, is sufficient to identify intermediate-risk patients who could gain pronounced benefits from ICD therapy [37]. QRS-T angle represents different pathophysiological pathway from conventional factors, and thus might add substantial value in the combined stratification. To support this, Strauss et al. screened the entire health system ECG databases in two hospitals and found that by stratification with the combination of QRS score and QRS-T angle, high-risk patients with a 1-year mortality of 8.8% to 13.9% could be identified [20]. In addition, QRS-T angle could also be used to identify relatively low-risk patients. In a study of patients with ischemic heart disease and ICD therapy, patients with a spatial QRS-T angle <100° had no event of ventricular arrhythmia after 2 years’ follow-up, and only 2% happened during further follow-up [3]. Despite all these evidences, translating QRS-T angle into clinical application needs more proofs and other studies are warranted to integrate QRS-T angle with other predictors in clinical practice.

Provided the predictive value of QRS-T angle in general population, one may ask whether it is cost-effective to perform routine screening of 12-lead ECG among subjects without a known cardiac disease. There is lack of studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of systematic ECG screening in the field of QRS-T angle, relative evidence overwhelmingly come from trials for the prevention of sudden cardiac death in athletes [38–40]. The American Heart Association (AHA) guideline does not support universal mandatory screening with 12-lead ECG in general populations of young healthy people (12–25 years old) [39,41], because a large body of studies demonstrate that 12-lead ECG test does not provide added mortality benefit supplemental to history and physical examination [39], and the cost is far excessive for public health system [42]. Given this evidence and that QRS-T angle was less predictive in general population in our study (RR < 2); we propose that mandatory screening with 12-lead ECG in the general population is unlikely to be cost-effective. Instead, it is more reasonable to take the advantage of the prognostic value of QRS-T angles in targeted populations (particularly populations with cardiovascular diseases) [39], in which 12-lead ECG is itself mandatory and the added benefits of QRS-T angles in risk stratification could be realized.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in our study. First, studies in our meta-analysis were conducted in different populations. Although this made stratified analyses in subgroup populations possible, the number of studies in each subpopulation was relatively limited. Besides, the definitions of subgroup populations were not uniform across studies. For instance, in patients with suspected CHD, some patients were enrolled with a symptom of acute ischemic chest pain; others were those undergoing a clinically indicated bicycle stress-test, or those with clinically diagnosed CHD. Thus, a phrase of “suspected CHD” was used in our study to indicate the potential heterogeneity.

Second, heterogeneity in the definitions of the cut-offs of QRS-T angles existed. As the population in each study varies, and QRS-T angles change with the pathophysiological status of the participants, the normal range of this angle in each population is different. Meanwhile, two methods of categorizing were used among these studies. Combining results from these two methods might bring in bias to our study. We conducted separate analyses to minimize this kind of bias, and both analyses yielded similar results. All these limitations made precise quantitative evaluation of prognostic value of QRS-T angle impossible. However, qualitative conclusions can still be addressed, evidenced by results from separate analyses. The consistency between adjusted and unadjusted analyses also reinforces the validity of our present findings.

Third, the extents of adjustment for confounding factors were not uniform across studies. The confounding factors for which were adjusted included demographic and risk factors (age, gender, presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, etc.), ECG parameters (STT abnormity, QRS duration, QTc interval, etc.), and drug use (diuretics, blockers, calcium channel blockers, etc.). Adjustments for certain confounders were absent in some studies, which could bring biases into individual studies. For instance, lack of adjustment for antihypertensive drugs might overlook the status of blood pressure controlling, which could subsequently affect the baseline QRS-T angles recorded in individual studies [43]. To maximally limit this kind of bias, we extracted the maximum-adjusted data from each study, and thus the bias is unlikely to be large.

Fourth, most of the individual studies were carried out in Europe, thus the results of this analysis might not be generalizable to other ethnic populations. Further studies in these populations are needed for the final determination.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis of all the evidence available demonstrates that both spatial and frontal QRS-T angles carry promising prognostic information on all-cause mortality in general population, in patients with suspected CHD and patients with heart failure. A wide spatial QRS-T angle also predicts a higher incidence of cardiac death. Given the great predictive value of QRS-T angles on all-cause/cardiac mortality, a combing stratification strategy in which QRS-T angle is of vital importance might be expected in near future. Of course, more solid evidence from well-designed studies is necessary.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xinxin Zhang from Center for Translational Medicine and Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Nanjing University School of Medicine, for her helpful discussion in the revision process.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 81070195, 81270281, and 81200148). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, writing of the report, and decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1. Kannel WB, Anderson K, McGee DL, Degatano LS, Stampfer MJ. Nonspecific electrocardiographic abnormality as a predictor of coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1987; 113: 370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Bruyne MC, Hoes AW, Kors JA, Hofman A, van Bemmel JH, Grobbee DE. Prolonged QT interval predicts cardiac and all-cause mortality in the elderly. The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J. 1999; 20: 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borleffs CJ, Scherptong RW, Man SC, van Welsenes GH, Bax JJ, van Erven L, et al. Predicting ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic heart disease: clinical application of the ECG-derived QRS-T angle. Circ Arrhythm electrophysiol. 2009; 2: 548–554. 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Macfarlane PW. The frontal plane QRS-T angle. Europace. 2012; 14: 773–775. 10.1093/europace/eus057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aro AL, Huikuri HV, Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, et al. QRS-T angle as a predictor of sudden cardiac death in a middle-aged general population. Europace. 2012; 14: 872–876. 10.1093/europace/eur393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lipton JA, Nelwan SP, van Domburg RT, Kors JA, Elhendy A, Schinkel AF, et al. Abnormal spatial QRS-T angle predicts mortality in patients undergoing dobutamine stress echocardiography for suspected coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2010; 21: 26–32. 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328332ee32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lown MT, Munyombwe T, Harrison W, West RM, Hall CA, Morrell C, et al. Association of frontal QRS-T angle—age risk score on admission electrocardiogram with mortality in patients admitted with an acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 109: 307–313. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Selvaraj S, Ilkhanoff L, Burke MA, Freed BH, Lang RM, Martinez EE, et al. Association of the frontal QRS-T angle with adverse cardiac remodeling, impaired left and right ventricular function, and worse outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014; 27: 74–82 e72. 10.1016/j.echo.2013.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rautaharju PM, Ge S, Nelson JC, Marino Larsen EK, Psaty BM, Furberg CD, et al. Comparison of mortality risk for electrocardiographic abnormalities in men and women with and without coronary heart disease (from the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am J Cardiol. 2006; 97: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang ZM, Prineas RJ, Case D, Soliman EZ, Rautaharju PM. Comparison of the prognostic significance of the electrocardiographic QRS/T angles in predicting incident coronary heart disease and total mortality (from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study). Am J Cardiol. 2007; 100: 844–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Torbal A, Kors JA, van Herpen G, Meij S, Nelwan S, Simoons ML, et al. The electrical T-axis and the spatial QRS-T angle are independent predictors of long-term mortality in patients admitted with acute ischemic chest pain. Cardiology. 2004; 101: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rautaharju PM, Kooperberg C, Larson JC, LaCroix A. Electrocardiographic abnormalities that predict coronary heart disease events and mortality in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative. Circulation. 2006; 113: 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rautaharju PM, Kooperberg C, Larson JC, LaCroix A. Electrocardiographic predictors of incident congestive heart failure and all-cause mortality in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative. Circulation. 2006; 113: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Bie MK, Koopman MG, Gaasbeek A, Dekker FW, Maan AC, Swenne CA, et al. Incremental prognostic value of an abnormal baseline spatial QRS-T angle in chronic dialysis patients. Europace. 2013; 15: 290–296. 10.1093/europace/eus306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubulis A, Bergfeldt L, Ryden L, Jensen J. Prediction of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction by the QRS-T angle and T vector loop morphology after angioplasty in stable angina pectoris: an 8-year follow-up. J Electrocardiol. 2010; 43: 310–317. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vend N, McNitt S, Kutyifa V, Zareba W. Predictive value of a widened QRS-T angle and low AVR amplitude in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2013; 10: S110–S111. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pavri BB, Hillis MB, Subacius H, Brumberg GE, Schaechter A, Levine JH, et al. Prognostic value and temporal behavior of the planar QRS-T angle in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2008; 117: 3181–3186. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.733451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kentt T, Karsikas M, Junttila MJ, Perkimki JS, Seppnen T, Kiviniemi A, et al. QRS-T morphology measured from exercise electrocardiogram as a predictor of cardiac mortality. Europace. 2011; 13: 701–707. 10.1093/europace/euq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whang W, Shimbo D, Levitan EB, Newman JD, Rautaharju PM, Davidson KW, et al. Relations between QRS|T angle, cardiac risk factors, and mortality in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Am J Cardiol. 2012; 109: 981–987. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strauss DG, Mewton N, Verrier RL, Nearing BD, Marchlinski FE, Killian T, et al. Screening entire health system ECG databases to identify patients at increased risk of death. Circ Arrhythm electrophysiol. 2013; 6: 1156–1162. 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamazaki T, Froelicher VF, Myers J, Chun S, Wang P. Spatial QRS-T angle predicts cardiac death in a clinical population. Heart Rhythm. 2005; 2: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kardys I, Kors JA, van der Meer IM, Hofman A, van der Kuip DA, Witteman JC. Spatial QRS-T angle predicts cardiac death in a general population. Eur Heart J. 2003; 24: 1357–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laukkanen JA, Di Angelantonio E, Khan H, Kurl S, Ronkainen K, Rautaharju P. T-wave inversion, QRS duration, and QRS/T angle as electrocardiographic predictors of the risk for sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 2014; 113: 1178–1183. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gotsman I, Keren A, Hellman Y, Banker J, Lotan C, Zwas DR. Usefulness of electrocardiographic frontal QRS-T angle to predict increased morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2013; 111: 1452–1459. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raposeiras-Roubin S, Virgos-Lamela A, Bouzas-Cruz N, Lopez-Lopez A, Castineira-Busto M, Fernandez-Garda R, et al. Usefulness of the QRS-T angle to improve long-term risk stratification of patients with acute myocardial infarction and depressed left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2014; 113: 1312–1319. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available: http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959; 22: 719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994; 50: 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151: 264–269, W264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldberger JJ, Subacius H, Patel T, Cunnane R, Kadish AH. Sudden cardiac death risk stratification in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63: 1879–1889. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goldberger JJ, Buxton AE, Cain M, Costantini O, Exner DV, Knight BP, et al. Risk stratification for arrhythmic sudden cardiac death: identifying the roadblocks. Circulation. 2011; 123: 2423–2430. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.959734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bailey JJ, Berson AS, Handelsman H, Hodges M. Utility of current risk stratification tests for predicting major arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38: 1902–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Church TR, Hodges M, Bailey JJ, Mongin SJ. Risk stratification applied to CAST registry data: combining 9 predictors. Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. J Electrocardiol. 2002; 35 Suppl: 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, et al. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51: 288–296. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Halkin A, Steinvil A, Rosso R, Adler A, Rozovski U, Viskin S. Preventing sudden death of athletes with electrocardiographic screening: what is the absolute benefit and how much will it cost? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60: 2271–2276. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Kligfield P, Levine BD, Viskin S, Chaitman BR, et al. Assessment of the 12-lead electrocardiogram as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12–25 years of age): a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64: 1479–1514. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brosnan M, La Gerche A, Kumar S, Lo W, Kalman J, Prior D. Modest agreement in ECG interpretation limits the application of ECG screening in young athletes. Heart Rhythm. 2015; 12: 130–136. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maron BJ, Thompson PD, Puffer JC, McGrew CA, Strong WB, Douglas PS, et al. Cardiovascular preparticipation screening of competitive athletes: addendum: an addendum to a statement for health professionals from the Sudden Death Committee (Council on Clinical Cardiology) and the Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee (Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young), American Heart Association. Circulation. 1998; 97: 2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leslie LK, Cohen JT, Newburger JW, Alexander ME, Wong JB, Sherwin ED, et al. Costs and benefits of targeted screening for causes of sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents. Circulation. 2012; 125: 2621–2629. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dern PL, Pryor R, Walker SH, Searls DT. Serial electrocardiographic changes in treated hypertensive patients with reference to voltage criteria, mean QRS vectors, and the QRS-T angle. Circulation. 1967; 36: 823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.