Abstract

Drug-induced lupus is a rare drug reaction featuring the same symptoms as idiopathic lupus erythematosus. Recently, with the introduction of new medicines in clinical practice, an increase in the number of illness-triggering implicated drugs has been reported, with special emphasis on anti-TNF-α drugs. In the up-to-date list, almost one hundred medications have been associated with the occurrence of drug-induced lupus. The authors present two case reports of the illness induced respectively by hydralazine and infliximab, addressing the clinical and laboratorial characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment.

Keywords: Acetyl-CoA C-Acetyltransferase; Acetylation; Autoimmunity; Hydralazine; Lupus erythematosus, cutaneous; Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

INTRODUCTION

Drug-induced lupus (DIL) was first reported in 1945 by Hoffman and it is estimated that over 10% of the cases of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are drug-induced. 1,2 Although the pathogenesis is not completely understood, genetic predisposition plays an important role.3,4 There is evidence of greater association in slow, acetylating patients, in which there is a genetically-mediated reduction of the synthesis of N-acetyltransferase. The anti-histone antibodies are considered markers of DIL.5

The clinical presentation is of insidious onset and can be similar to that of SLE, chronic or subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.2,6 The most common symptoms are arthralgia and arthritis, sudden erythema and polycyclic lesions located in sun-exposed areas, similar to the presentation of subacute lupus erythematosus. Severe systemic involvement is rare, with fewer occurrences of alterations in the central nervous, renal, and hematopoietic systems.4,7

Recently, with the introduction of new drugs in clinical practice, an increase in the number of drugs causing the disease has been reported.2 Anti-TNF therapies (infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab) are considered potential inducers of SLE.8,9 The clinical and laboratory tests differ from classically described DIL.

In the case of DIL associated with anti-TNF-α, the positivity of doubled strand- DNA antibodies (DS-DNA) is most commonly observed.9,10 Although the pathogenesis of SLE induced by anti-TNF is not fully elucidated, drug interruption is the mainstay of the treatment, which is also the first step when DIL is secondary to other drugs. 2,8 In addition, the use of medications to control symptoms, such as anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can be indicated. In extensive or refractory cases, systemic corticosteroid may be employed until clinical symptons resolve.7,9

This paper presents two cases of hydralazine- and infliximab-induced lupus with clinical and histopathologic features. The authors suggest that the two conditions are different based on distinct pathogenesis.

CASE REPORT

Case 1: A 54-year-old male patient with hypertension, taking hydralazine for four years, had been presenting with been presenting erythematous, scaly and edematous papules on the trunk, back, upper limbs and sun-exposed areas for the last two months (Figure 1). Laboratory tests: ANA 1:640 homogeneous nuclear pattern and positive anti-histone. Histopathology was compatible with lupus erythematosus (Figure 2). Hydralazine was discontinued and prednisone was prescribed. There was rapid improvement of skin lesions, and resolution of symptoms after 4 weeks (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Drug-induced lupus by hydralazine. Erythematous, scaly and edematous papules on the back (A), trunk and upper limbs (B)

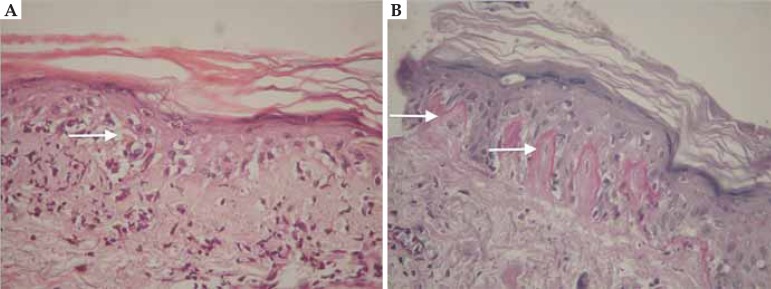

FIGURE 2.

Drug-induced lupus by hydralazine. Histopathology: hyperkeratosis, thinning of the epidermis, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer (A - white arrow), keratinocyte apoptosis, pigmentary incontinence, perivascular and periadnexal infi ltrate. Thickening and hyalinization of the basement membrane (B - white arrow)

FIGURE 3.

Drug-induced lupus by hydralazine. Fig. (A, B): There was rapid improvement of skin lesions. Fig. (C, D): Resolution of symptoms after 4 weeks of drug discontinuation

Case 2: A 37-year-old male patient, bearer of ulcerative colitis, started on infliximab at a dose of 5 mg/kg. After a two-month therapy he presented erythematous, brownish, infiltrated, rough surface lesions on the face and ear lobes (Figure 4). Laboratory test: ANA 1:320 with peripheral pattern. Histopathology was compatible with lupus erythematosus (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Drug-induced lupus by anti-TNF-α. Fig. 4 (A): Erythematous, brownish, infiltrated, rough surface lesions on the face. Figure 4 (B): The same pattern involving preauricular and ear lobes

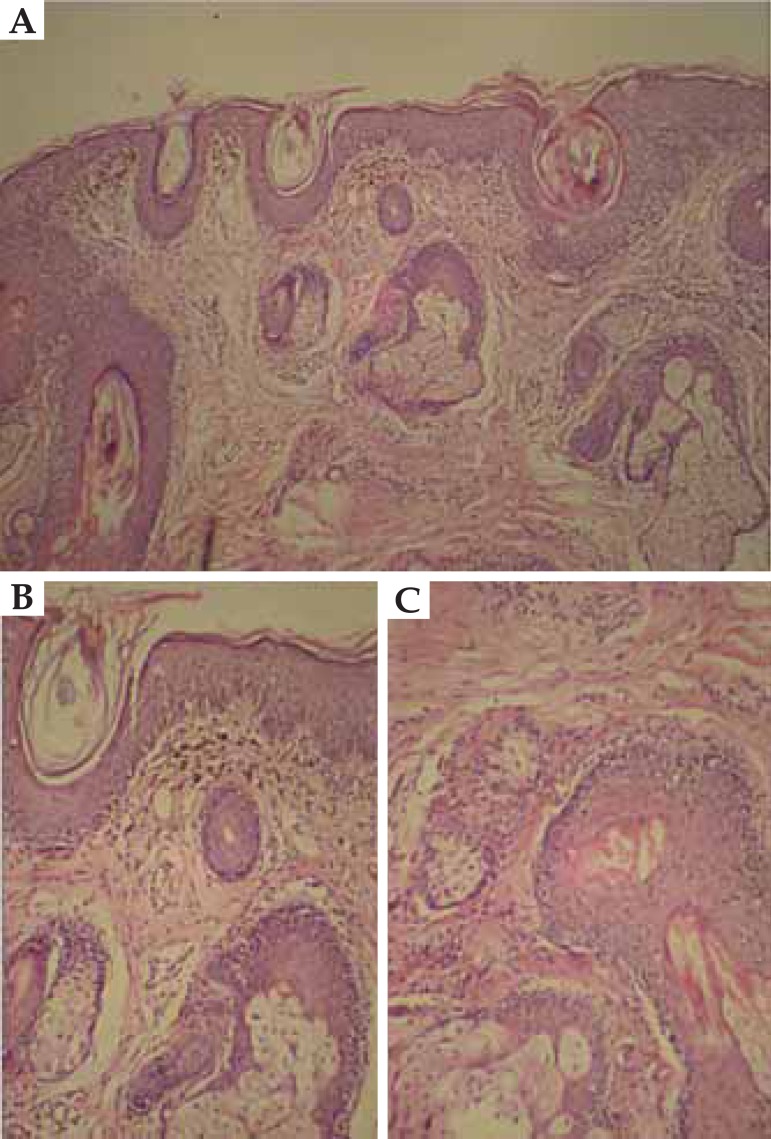

FIGURE 5.

Drug-induced lupus by anti-TNF-α. Fig. (A, B, C). Histopathology: follicular hyperkeratosis, vacuolization of the basal layer of the epidermal and follicular epithelium, superficial perivascular mononuclear infi ltrate and melanophages in the papillary dermis

DISCUSSION

Drugs associated with induction of lupus erythematosus are classified into groups according to the level of available scientific evidence of causal relationship, and hydralazine is definitely regarded as a drug capable of inducing lupus (controlled studies).2 Anti-TNF-α therapies are drugs that have recently been reported in the induction of the disease.8,9 The mechanisms that induce lupus with the use of hydralazine and anti-TNF-α therapies are distinct.2,7,8

Hydralazine is metabolizated by the liver through acetylation by the enzyme N-acetyltransferase. The rate of acetylation is genetically determined, and the slow or fast acetylator phenotype is controlled by a single, recessive gene associated with low activity of hepatic acetyltransferase.2 Since the elimination of hydralazine depends mainly on acetylation, acetylate individuals may exhibit toxic and/or immunological effects, such as DIL related to drug accumulation.7 Hydralazine also inhibits T-cell DNA methylation, which has the function of deleting non-essential or potentially-deleterious-to-cell-function genes, and induces self-reactivity in these cells, resulting in autoimmunity.4

Infliximab is a chimeric, human-murine, monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to both soluble and transmembrane forms of TNF-α.8 The development of lupus erythematosus during anti-TNF-α therapy is unclear, though three mechanisms have been proposed.9 The first is that anti-TNF-α inhibits Th1 cytokine production, increasing the production of Th2 cytokines, leading to the production of autoantibodies and a lupus-like syndrome.10 Another hypothesis assumes that systemic inhibition of TNF-α might interfere with apoptosis, affecting the clearance of nuclear debris and apoptotic neutrophils by phagocytes, thus promoting the production of autoantibodies to DNA and other nuclear antigens. In the third hypothesis, the anti-TNF-α therapy could inhibit cytotoxic T cells, reducing the elimination of autoantibodies produced by B-cells.8-10

Due to the difficulties encountered in diagnosis, some criteria were proposed7 for guidance and the patient in case 1 presented enough features to be diagnosed with DIL: continuous use of the drug for at least 60 days; sudden and persistent erythema; positive anti-histone antibodies and ANA with titers above 1/160 and disappearance of the lesions and symptoms after at least two weeks of drug discontinuation. In addition, the patient's histopathology was compatible with lupus erythematosus.

Certain characteristics aid in the diagnosis of anti-TNF-α-induced lupus: onset of symptoms time-related to the use of anti-TNF-α therapy, at least one positive serology (ANA, anti-DS-DNA) and one non-serological criterion (arthritis, serositis, haematological disorders - anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia - or malar rash).3,4 In case 2, the patient had the 3 main characteristics listed above (onset of symptoms, positive serology and malar rash), in addition to typical histopathological features of lupus erythematosus.

Histopathological findings of lupus erythematosus aid in the diagnosis but are not mentioned among the criteria for defining classic DIL or anti-TNF-α drug-induced lupus.

The suspension of anti-TNF-α therapy is controversial in asymptomatic patients with positive ANA.2 Systemic corticosteroids were not initiated in case 2 due to the benignity of the clinical presentation. Both patients showed clinical improvement during follow-up.

The recognition of the fact that the condition is drug-induced avoids unnecessary investigations and enables appropriate management of the patient. More studies are necessary to better elucidate the pathogenesis of anti-TNF-induced lupus.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Financial Support: None.

How to cite this article: Quaresma MV, Bernardes Filho F, Oliveira FB, Pockstaller MP, Dias MFRG, Azulay DR. Anti-TNF-α and classical drug-induced lupus. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 Suppl 1):S125-9

Work performed at the Instituto de Dermatologia Professor Rubem David Azulay, Santa Casa da Misericórdia do Rio de Janeiro - Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brasil.

References

- 1.Hoffman BJ. Sensitivity to sufadizine resembling acute disseminated lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Physiol. 1945;51:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mota LMH, Haddad GP, Lima RAC, Carvalho JF, Muniz-Junqueira MI, Neto LLS, Lima FAC. Drug-induced lupus - from basic to spplied immunology. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2007;47:431–437. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borba EF, Latorre LC, Brenol JCT, Kayser C, Silva NA, Zimmermann AF. Consensus of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2008;48:196–207. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677–2686. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atzeni F, Marrazza MG, Sarzi-Puttini P, Carrabba M. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Reumatismo. 2003;55:147–154. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2003.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Capsoni F, Lubrano E, Doria A. Drug induced lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2005;38:507–518. doi: 10.1080/08916930500285857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duarte AA. Colagenoses e a Dermatologia. 2. ed. São Paulo: DiLivros; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almoallim H, Al-Ghamdi Y, Almaghrabi H, Alyasi O. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-a Induced Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:315–319. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wetter DA, Davis MD. Lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy in 14 patients during an 8-year period at Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:979–984. doi: 10.4065/84.11.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azulay RD, Azulay DR. Azulay DR. Dermatologia. 6 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2013. Doenças Autoimunes de Interesse Dermatológico; pp. 778–781. [Google Scholar]