Abstract

The management of endoleaks remains an inherent challenge to endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), particularly as evolving techniques and devices have allowed treatment of increasingly complex aneurysm anatomy. Endovascular techniques are the favored modality for endoleak repair and include techniques to bridge the endoleak defector and embolize the endoleak nidus and inflow/outflow vessels. Conversion to surgical repair remains the definitive option in cases where less invasive methods have failed or are precluded. In this article, the authors review evidence on the indications, approach, and outcomes of current techniques for endoleak management.

Keywords: endovascular aneurysm repair, endoleak, embolization, interventional radiology

Objectives: Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to discuss indications for treatment of endoleaks as well as specific management strategies for each endoleak type.

Accreditation: This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) and Thieme Medical Publishers, New York. TUSM is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit: Tufts University School of Medicine designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Since the advent of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)in the 1990s, experience and stent-graft technology have continued to grow, allowing treatment of increasingly complex aneurysms. With these advances have come continued challenges of endoleak management, which are particularly relevant for cases of hostile aneurysm anatomy. Type I and III endoleaks, characterized by direct communication between systemic and aneurysm sac compartments, pose higher risk of aneurysm rupture1 and are therefore aggressively treated. The natural history of type II endoleaks remains a debated topic, with evidence suggesting an indolent natural history in many cases. Criteria for intervention consequently vary between groups. Approaches to the treatment of endoleak are dictated by endoleak type and include endovascular, surgical, and combined approaches, which have evolved in concert with improvements in endograft technology.

Type I Endoleak

Type I endoleaks result from failure of the stent graft to achieve a circumferential seal at the proximal (IA) or distal (IB) attachment sites, resulting in systemic pressurization of the aneurysm sac and thereby necessitating prompt treatment. With increasing experience and advances in EVAR technology, hostile proximal aortic neck anatomy (i.e., short, angulated, conical shape, or circumferential thrombus or calcium), which required surgery earlier, is now repairable by endovascular means, but comes with increased risk of type IA endoleak. Technologies such as cone-beam computed tomography (CT) have improved sensitivity for intraoperative detection of type I endoleaks,2 but there are late type I endoleaks resulting from endograft failure or migration, often in cases of hostile neck anatomy.

Initial treatment for type IA endoleaks is balloon angioplasty of the proximal attachment site, aimed at remodeling the stent graft to achieve adequate seal. If angioplasty is unsuccessful, balloon expandable bare metal stents such as Palmaz stents (Cordis Endovascular, Warren, NJ) can be deployed over the affected attachment site to promote apposition of the proximal stent graft with the aortic wall. In cases of undersized or maldeployed endografts, covered extension cuffs, which are usually matched in size and material to the native endograft, offer another option to bridge the endoleak defect.3 A comparison of long-term outcomes following bare metal stent versus extension cuff repair by Rajani et al demonstrated statistically equivalent outcomes between the two groups, but with a trend toward increased recurrent endoleak in the extension cuff group.4 In addition to these conventional techniques, there are several new devices, such as EndoStaples and EndoAnchors (Aptus Endosystems, Sunnyvale, CA),5 which mechanically attach the proximal endograft with the aortic wall and have demonstrated promising early results for both prophylaxis and treatment of type IA endoleaks.

In cases where the aforementioned techniques are precluded or have failed, particularly when there is insufficient space between the endograft and renal arteries, embolization provides an alternative treatment option. From a femoral approach, a reverse curve catheter can be used to probe the edge of the stent graft to access the perigraft endoleak space. Diagnostic angiography can then be performed to delineate the endoleak anatomy and to rule out a concurrent type II endoleak (i.e., via the inferior mesenteric artery), which can occur in delayed presentations and in some cases contribute to keeping the type I endoleak open. A microcatheter is advanced into the perigraft space for embolization of the endoleak. Several series have described durable treatment using various combinations of coils and liquid embolics such as NBCA glue (Trufill, Cordis, Miami, FL) and Onyx (ethylene vinyl-alcohol copolymer, ev3, Plymouth, MN)1 6 7 8 9

Type IB endoleaks are generally easier to manage than IA, with numerous available iliac extender limbs, covered stents, and bare metal stents to close the endoleak defect. In cases for which exclusion of an internal iliac artery is necessitated, the artery should be embolized prior to addressing the attachment site leak to avoid subsequent type II endoleaks. Notably, flow to one of the internal iliac arteries should be preserved when possible to avoid intractable buttock claudication. In the rare cases when the aforementioned techniques are unsuccessful, embolization of the endoleak can be performed with a simple curved catheter, with several authors reporting successful results using NBCA.1 8 10 Despite these advances in endovascular techniques, there are still cases that require surgical repair for definitive treatment.

Type II Endoleak

Type II endoleaks result from retrograde filling of the aneurysm sac from branch vessels, most often via inferior mesenteric or lumbar arteries, and remain the most common endoleak type, occurring in 8 to 10% of cases.11 12 Unlike type I endoleaks, for which prompt management is agreed upon, treatment of type II endoleaks has been a long debated issue. Retrograde arterial flow can cause increased intrasac pressures, promote further sac enlargement, and consequently predispose to aneurysm rupture.13 However, increasing data on the natural history of type II endoleaks suggest that the majority of aneurysms will remain stable or decrease in size due to slow flow and spontaneous thrombosis. The EUROSTAR registry showed no statistically significant difference in the incidence of 2-year post-EVAR aneurysm rupture between patients with (1.8%) and without type II endoleak (0.9%),14 a conclusion that has since been supported by results from other groups. In light of these data, the criteria for intervention remain controversial. The most commonly accepted criteria are persistent endoleak for longer than 6 months13 or sac expansion of >5 mm.15 16 Additional proposed criteria include the presence of a large nidus,17 18 19 >3 feeding and/or draining arteries,17 18 19 feeding artery diameter >4 mm,17 18 and high flow velocities within the aneurysm sac.20

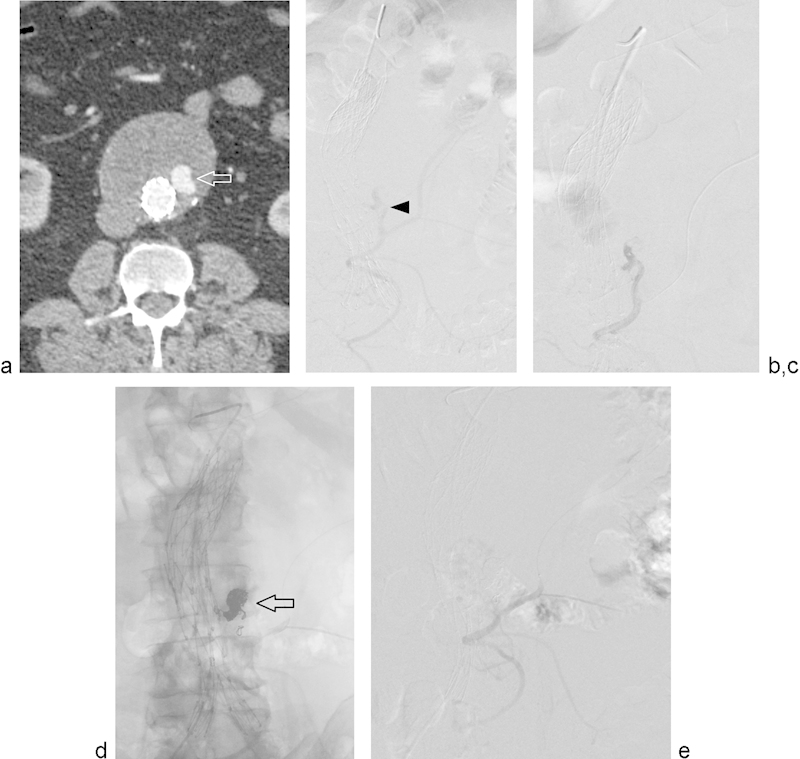

In cases for which treatment is merited, endovascular embolization of the feeding vessel(s) and endoleak nidus is the preferred mode of treatment (Fig. 1). Access to the aneurysm sac is most commonly attained via transarterial or translumbar (direct sac puncture) approaches. In a metaanalysis by Sidloff et al, translumbar embolization had superior durability, with 19% failure rate at follow-up of 3 to 22 months, versus 37.5% failure rate at follow-up of 4 to 25 months for transarterial embolization.12 A series by Stavropoulos et al, however, demonstrated no significant difference in durability between the two techniques, with failures rates of 28 and 22% for translumbar and modified transarterial approaches, respectively, with mean follow-up of 18.7 months.21

Fig. 1.

Type II endoleak treated with transarterial embolization. (a) Computed tomography angiogram (CTA) performed ∼3 years following EVAR demonstrates contrast opacification of the aneurysm sac (arrow) on arterial phase imaging and interval increased aneurysm sac diameter compared with prior CTA (not shown). (b) Arteriogram of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) demonstrates opacification of a type II endoleak (arrowhead) via the middle colic artery. (c) Selective arteriogram of the endoleak via a microcatheter better delineates endoleak anatomy. (d) Postembolization unsubtracted arteriogram shows coils in the endoleak sac (arrow). (e) Postembolization subtracted angiogram shows no residual filling of the endoleak sac.

The determination of whether transarterial embolization is feasible is based on the anatomy of the arteries supplying the type 2 endoleak. Selective angiography of the inflow vessel(s) should be first performed to delineate the degree of collateralization and vessel tortuosity. If the endoleak cavity can be accessed via the collaterals supplying the IMA or lumbar artery, then transarterial endoleak embolization can be performed. IMA endoleaks can often be opacified from the superior mesenteric artery via the arc of Riolan or other middle colic and marginal artery branches. Transarterial embolization is possible if there is a navigable retrograde course to the origin of the IMA via these vessels. If the IMA origin cannot be catheterized, transarterial embolization is contraindicated due to the risk of colonic ischemia from proximal nontarget embolization. Lumbar arterial endoleaks can be accessed through the internal iliac artery, most commonly via ascending iliolumbar branches. Collateralization with adjacent lumbar arteries and the median sacral artery is common, so proximal embolization without direct occlusion of the endoleak nidus will lead to posttreatment reconstitution by collaterals. Selective catheterization is performed with coaxial microcatheter systems through which mechanical, liquid, or combined embolic agents can be delivered.21 22 23 At the authors' institution, once the endoleak cavity has been accessed, it is embolized with platinum microcoils. As the endoleak cavity is filled with coils, the microcatheter is pulled back and the feeding artery (IMA or lumbar) is embolized with coils.

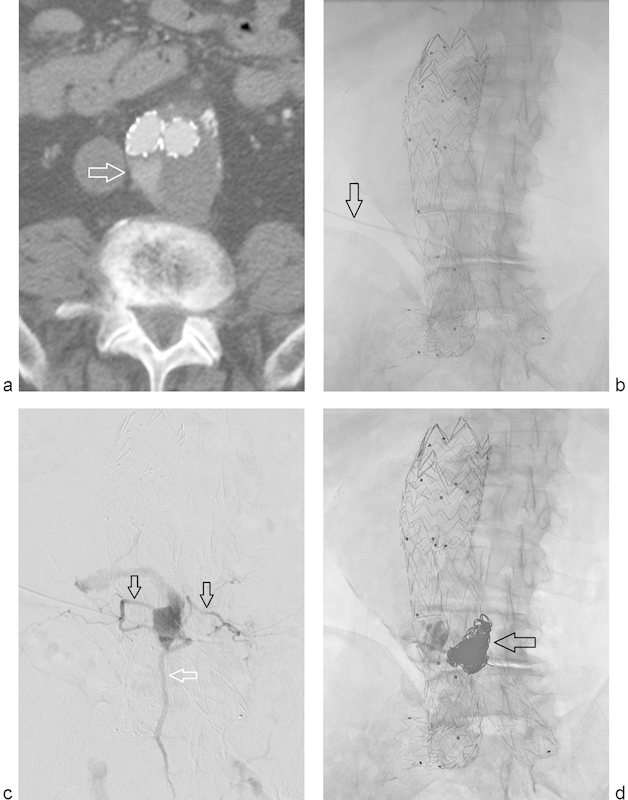

A transarterial approach can be difficult or impossible in cases of occluded internal iliac or inferior mesenteric arteries, prior transarterial embolization, or arterial feeders that are too tortuous or too small to catheterize. In these circumstances, direct sac puncture, preferably from a prone left translumbar approach, provides an alternate access route (Fig. 2). Access to the endoleak sac is achieved under fluoroscopic guidance. The CTA is used to identify anatomic landmarks including the spine, endograft, and calcifications in the aneurysm wall; the goal is to access the portion of the endoleak that enhances on the CTA portion of the diagnostic CT. Using these anatomic markers, the access needle is introduced under fluoroscopic guidance into the aneurysm and subsequently into the endoleak cavity. A slight “give” can be felt as the aneurysm wall is traversed, and blood return will confirm intra-endoleak sac position. van Bindsbergen et al have described a technique for real time three-dimensional needle guidance using cone-beam CT coregistered to fluoroscopy, which can potentially facilitate treatment of small niduses and decrease radiation and contrast doses compared with traditional methods.24 Once intrasac position is attained, diagnostic angiography should be performed to evaluate needle position and delineate the anatomy of the inflow and outflow vessels.

Fig. 2.

Type II endoleak treated with translumbar embolization. (a) CTA performed ∼2 years following EVAR demonstrates contrast opacification of the aneurysm sac on arterial phase imaging (arrow). (b) Frontal fluoroscopic image demonstrates access needle trajectory using left translumbar approach (arrow). (c) Arteriogram via the access needle delineates the endoleak sac anatomy with opacification of bilateral lumbar arteries (black arrows) and the median sacral artery (white arrow). (d) Postembolization frontal fluoroscopic image demonstrates coils within the endoleak sac (arrow).

Although the left translumbar approach is preferred, modified direct sac puncture techniques are required in certain cases. Prone right-sided percutaneous transcaval technique may be necessary due to position of the endoleak or interposed bowel and organs. Traversal of the IVC has not been shown to predispose to hemorrhage or arteriovenous fistulae, but there is the potential for complications of malpositioned coils entering the IVC.25 Mansueto et al have described a transvenous approach to transcaval embolization, using a curved puncture needle system for sac access from the IVC, which affords single rather than double IVC wall puncture and improved patient comfort with supine positioning compared to percutaneous technique.26 Uthoff et al describe a supine transabdominal approach for anteriorly located IMA endoleaks, which allows for simultaneous transarterial embolization.27

Regardless of approach, once the sac is accessed embolization can be performed. The authors' technique is to place 0.035-in. platinum coils through the translumbar access catheter to embolize the endoleak sac. Occasionally, the inflow or outflow arteries demonstrate accessible anatomy for coil embolization, although this occurs in less than 20% of translumbar embolization cases. After coils have been placed in the endoleak sac and flow has slowed down, n-BCA glue is injected into the sac for further embolization, after which the catheter is pulled. Care is taken not to have n-BCA flow into the feeding IMA or lumbar arteries from a translumbar approach due to the risks of nontarget embolization.

The options for embolic agents include mechanical devices and liquids, used in combination or alone, with choice of embolic dictated by patient anatomy and operator preference. Coils are the mainstay of mechanical options and include stainless steel and platinum varieties, the former causing fewer artifacts on follow-up CTA, while the latter can form tighter coil nests due to greater metal compliance. Amplatzer vascular plugs (AGA Medical, Golden Valley, MN) have also been used for larger endoleaks for which the sac volume would be impractical for coil occlusion alone.23 NBCA or Onyx (ev3, Plymouth, MN) embolization can also reduce the number of coils required to achieve occlusion, thereby reducing procedural time and radiation. NBCA remains the most widely used liquid agent, but increasing experience with Onyx suggests potential advantages including superior control for precise nidus penetration, decreased risk of catheter adherence and injury to the vessel wall, decreased risk of distal embolization, and increased ease of fluoroscopic monitoring due to radio-opacity,22 23 28 noting that cost in the United States remains a major barrier for widespread adoption. Thrombin has also been used by some groups,26 but has not achieved general adoption owing to increased risk of nontarget embolization.29 The technical success of embolization is largely assessed on angiography with the goal being complete occlusion of the endoleak. Intrasac pressure measurements have also been described as a means to quantitatively assess adequacy of occlusion.26 30

Given the proliferation and evolution of the described endovascular techniques, surgical treatment for type II endoleaks is now needed in only a small minority of cases. In addition to conventional surgical repair, modified techniques including robot-assisted laparoscopic ligation of the IMA31 and combined endovascular and laparoscopic approaches have shown successful outcomes in case reports and small series.32 33

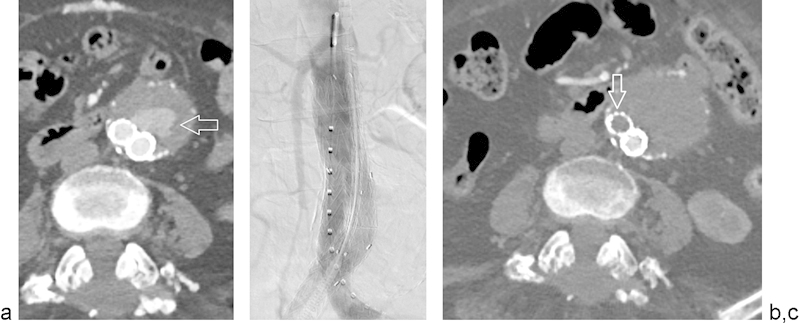

Type III Endoleak

Type III endoleaks result from device failure, most commonly from junctional leak or separation of modular graft components (IIIA), and less frequently from fabric erosion (IIIB). The mechanisms may include stresses from tortuous anatomy and wear from movable endograft parts. Although not as common as Type I or II endoleaks, these endoleaks can result in rapid aneurysm expansion and rupture and require prompt intervention. Endovascular repair is predominantly via deployment of a new bifurcated stent graft over the defective area, with angioplasty to promote optimal seal (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Type III endoleak treated with aorto-uni-iliac graft, left iliac limb occluder, and femoral–femoral bypass graft. (a) Arteriogram demonstrates type III endoleak (arrow) arising from the junction of the aortic and left iliac components of the stent graft. (b) Arteriogram demonstrates pre-deployment positioning of an aorto-right uni-iliac stent graft with left iliac limb occluder. (c) Postprocedural CTA demonstrates opacified right iliac limb stent graft, left iliac limb occlude (arrow), and no residual contrast opacification of the aneurysm lumen.

Type IV Endoleak

Type IV endoleaks are secondary to graft porosity and are typically seen in the immediate postdeployment angiogram, with self-resolution once the patients coagulation status returns to baseline. These endoleaks have been largely eliminated with advances in graft fabric.

Endotension (Type V Endoleak)

Endotension refers to an enlarging aneurysm sac in the absence of demonstrable endoleak. The etiology remains to be fully elucidated, with proposed mechanisms including transmitted pressure to the aneurysm sac from the adjacent stent graft and thrombus or persistent flow beneath the resolution of available imaging modalities.34 Observation may be appropriate in certain cases, as these endoleaks are not the result of a direct arterial communication, but the precise criteria for conservative management are not fully defined. The mainstay of treatment remains conversion to open repair, which provides durable treatment, but associated with an increased risk of morbidity; endovascular relining techniques have developed as a less invasive option to reinforce the native endograft. Some authors have reported successful results using various endovascular methods including conversion from polytetrafluoroethylene endografts to less porous alternatives such as polyester,35 or deployment of proximal and distal extension cuffs.36 Additional techniques such as aspiration or laparoscopic fenestration of the aneurysm sac have been reported in small series.

Conclusion

The management of endoleak remains one of the inherent challenges to the endovascular treatment of aortic aneurysms. Type I and III endoleaks, defined by a persistent direct communication between the aneurysm sac and systemic circulation, continue to require prompt repair. Type II endoleak management remains more controversial, with current evidence supporting treatment in those cases demonstrating continued aneurysm expansion or persistent endoleak. Endovascular means for endoleak repair have evolved to include mechanical devices to bridge or reinforce endoleak defects as well as varied approaches to access and embolize the endoleak nidus. Conversion to surgical repair remains the definitive option in cases for which endovascular treatments are unsuccessful or precluded.

References

- 1.Maldonado T S, Rosen R J, Rockman C B. et al. Initial successful management of type I endoleak after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair with n-butyl cyanoacrylate adhesive. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(4):664–670. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00729-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biasi L, Ali T, Hinchliffe R, Morgan R, Loftus I, Thompson M. Intraoperative DynaCT detection and immediate correction of a type Ia endoleak following endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32(3):535–538. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas B G, Sanchez L A, Geraghty P J, Rubin B G, Money S R, Sicard G A. A comparative analysis of the outcomes of aortic cuffs and converters for endovascular graft migration. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(6):1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajani R R, Arthurs Z M, Srivastava S D, Lyden S P, Clair D G, Eagleton M J. Repairing immediate proximal endoleaks during abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5):1174–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan W D Jr, Mehta M, Varnagy D. et al. Results of the ANCHOR prospective, multicenter registry of EndoAnchors for type Ia endoleaks and endograft migration in patients with challenging anatomy. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(4):885–9200. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golzarian J, Struyven J, Abada H T. et al. Endovascular aortic stent-grafts: transcatheter embolization of persistent perigraft leaks. Radiology. 1997;202(3):731–734. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi S Y, Lee Y, Lee K H. et al. Treatment of type I endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm: usefulness of N-butyl cyanoacrylate embolization in cases of failed secondary endovascular intervention. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grisafi J L, Boiteau G, Detschelt E, Potts J, Kiproff P, Muluk S C. Endoluminal treatment of type IA endoleak with Onyx. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(5):1346–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun J Y, Morgan R. Transcatheter embolisation of type 1 endoleaks after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair with Onyx: when no other treatment option is feasible. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45(2):141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen R J Green R M Endoleak management following endovascular aneurysm repair J Vasc Interv Radiol 200819(6, Suppl):S37–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dangas G, O'Connor D, Firwana B. et al. Open versus endovascular stent graft repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(10):1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidloff D A, Stather P W, Choke E, Bown M J, Sayers R D. Type II endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair. Br J Surg. 2013;100(10):1262–1270. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones J E, Atkins M D, Brewster D C. et al. Persistent type 2 endoleak after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with adverse late outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Marrewijk C, Buth J, Harris P L, Norgren L, Nevelsteen A, Wyatt M G. Significance of endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: the EUROSTAR experience. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(3):461–473. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.118823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaikof E L Brewster D C Dalman R L et al. The care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: the Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines J Vasc Surg 200950(4, Suppl):S2–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moll F L, Powell J T, Fraedrich G. et al. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms clinical practice guidelines of the European society for vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(1) 01:S1–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keedy A W, Yeh B M, Kohr J R, Hiramoto J S, Schneider D B, Breiman R S. Evaluation of potential outcome predictors in type II Endoleak: a retrospective study with CT angiography feature analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(1):234–240. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parent F N, Meier G H, Godziachvili V. et al. The incidence and natural history of type I and II endoleak: a 5-year follow-up assessment with color duplex ultrasound scan. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(3):474–481. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.121848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bargellini I, Napoli V, Petruzzi P. et al. Type II lumbar endoleaks: hemodynamic differentiation by contrast-enhanced ultrasound scanning and influence on aneurysm enlargement after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(1):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arko F R, Filis K A, Siedel S A. et al. Intrasac flow velocities predict sealing of type II endoleaks after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(1):8–15. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stavropoulos S W, Park J, Fairman R, Carpenter J. Type 2 endoleak embolization comparison: translumbar embolization versus modified transarterial embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20(10):1299–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abularrage C J, Patel V I, Conrad M F, Schneider E B, Cambria R P, Kwolek C J. Improved results using Onyx glue for the treatment of persistent type 2 endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(3):630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khaja M S, Park A W, Swee W. et al. Treatment of type II endoleak using Onyx with long-term imaging follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37(3):613–622. doi: 10.1007/s00270-013-0706-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Bindsbergen L, Braak S J, van Strijen M J, de Vries J P. Type II endoleak embolization after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair with use of real-time three-dimensional fluoroscopic needle guidance. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(9):1443–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stavropoulos S W Carpenter J P Fairman R M Golden M A Baum R A Inferior vena cava traversal for translumbar endoleak embolization after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair J Vasc Interv Radiol 200314(9, Pt 1):1191–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansueto G, Cenzi D, Scuro A. et al. Treatment of type II endoleak with a transcatheter transcaval approach: results at 1-year follow-up. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(6):1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uthoff H, Katzen B T, Gandhi R, Peña C S, Benenati J F, Geisbüsch P. Direct percutaneous sac injection for postoperative endoleak treatment after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.03.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massis K, Carson W G III, Rozas A, Patel V, Zwiebel B. Treatment of type II endoleaks with ethylene-vinyl-alcohol copolymer (Onyx) Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2012;46(3):251–257. doi: 10.1177/1538574412442401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gambaro E, Abou-Zamzam A M Jr, Teruya T H, Bianchi C, Hopewell J, Ballard J L. Ischemic colitis following translumbar thrombin injection for treatment of endoleak. Ann Vasc Surg. 2004;18(1):74–78. doi: 10.1007/s10016-003-0102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum R A, Carpenter J P, Cope C. et al. Aneurysm sac pressure measurements after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(1):32–41. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.111807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin J C, Eun D, Shrivastava A, Shepard A D, Reddy D J. Total robotic ligation of inferior mesenteric artery for type II endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23(2):2.55E21–2.55E23. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou W, Lumsden A B, Li J. IMA clipping for a type ii endoleak: combined laparoscopic and endovascular approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16(4):272–275. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200608000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling A J, Pathak R, Garbowski M, Nadkarni S. Treatment of a large type II endoleak via extraperitoneal dissection and embolization of a collateral vessel using ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx) J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18(5):659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toya N, Fujita T, Kanaoka Y, Ohki T. Endotension following endovascular aneurysm repair. Vasc Med. 2008;13(4):305–311. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08094850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith S T, Clagett G P, Arko F R. Endovascular conversion with femorofemoral bypass as a treatment of endotension and aneurysm sac enlargement. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(2):395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kougias P, Lin P H, Dardik A, Lee W A, El Sayed H F, Zhou W. Successful treatment of endotension and aneurysm sac enlargement with endovascular stent graft reinforcement. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(1):124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]