Abstract

Purpose

Analysis of mandibular biomechanics could help with understanding the mechanisms of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders (TMJDs), such as osteoarthritis (TMJ-OA), by investigating the effects of injury or disease on TMJ movement. The objective of the present study was to determine the functional kinematic implications of mild TMJ-OA degeneration caused by altered occlusion from unilateral splints in the rabbit.

Materials and Methods

Altered occlusion of the TMJ was mechanically induced in rabbits by way of a unilateral molar dental splint (n = 3). TMJ motion was assessed using 3-dimensional (3D) skeletal kinematics twice, once before and once after 6 weeks of splint placement with the splints removed, after allowing 3 days of recovery. The relative motion of the condyle to the fossa and the distance between the incisors were tracked.

Results

An overall decrease in the range of joint movement was observed at the incisors and in the joint space between the condyle and fossa. The incisor movement decreased from 7.0 ± 0.5 mm to 6.2 ± 0.5 mm right to left, from 5.5 ± 2.2 mm to 4.6 ± 0.8 mm anterior to posterior, and from 13.3 ± 1.8 mm to 11.6 ± 1.4 mm superior to inferior (P < .05). The total magnitude of the maximum distance between the points on the condyle and fossa decreased from 3.6 ± 0.8 mm to 3.1 ± 0.6 mm for the working condyle and 2.8 ± 0.4 mm to 2.5 ± 0.4 mm for the balancing condyle (P < .05). The largest decreases were seen in the anteroposterior direction for both condyles.

Conclusion

Determining the changes in condylar movement might lead to a better understanding of the early predictors in the development of TMJ-OA and determining when the symptoms become a chronic, irreversible problem.

For patients experiencing pain associated with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders (TMJDs), normal life activities such as eating, talking, and even sleeping can be drastically impaired. TMJDs are multifactorial and complex.1 The signs and symptoms of TMJDs include joint pain, limited mouth opening, jaw deviation, clicking, locking, dislocation, and pain in the masticatory muscles during jaw movement.2 Although a heterogeneous syndrome that can involve the joint and the muscles of mastication, osteoarthritis (OA) is present in up to 15% of those with TMJD,3 and pain is the primary complaint associated with the loss of function.1,4,5 TMJ-OA is the pathologic process of joint degeneration, including irreparable abrasion of articular cartilage and thickening and remodeling of the underlying bone.6 A number of potential causes of TMJ-OA have been implicated, including trauma and parafunctional habits, such as teeth clenching and grinding.

We hypothesized that the altered joint movement or travel path (kinematics) caused by trauma or parafunctional habits is one of the underlying mechanisms of progressive TMJ-OA. Establishing the link between altered TMJ kinematics and joint degeneration could have an immediate clinical effect. Understanding this relationship could provide guidance to surgeons regarding the window in which interventions to normalize malocclusion associated with trauma might be most successful. This knowledge could support the use of TMJ kinematic analysis as a diagnostic tool with which to identify the basis for TMJ pain in at least a subpopulation of patients with TMJD. They might also suggest that strategies to normalize altered TMJ kinematics might be effective for the treatment of TMJ pain in these patients.

Establishing a link between kinematics and TMJ-OA has been hindered by the dearth of data linking the changes observed in preclinical animal models to the development and manifestation of the pathology of the human state. Of ongoing debate is the question of whether TMJ disc displacement precedes degeneration of the condylar cartilage. As a potential explanation for the relatively limited efficacy of interventions focused on the TMJ disc, the results from our rabbit TMJ-OA model have shown that condylar cartilage remodeling (stiffening and loss of the subchondral layer) occurs with a disc in its proper anatomic position.7 Because the condylar cartilage resembles the early stages of OA, it is not known whether the TMJ kinematics were altered. If the joint kinematics do not return to normal, they could be a primary driver for additional joint degeneration and end-stage OA.

The objective of the present study was to determine the functional kinematic implications of the TMJ with mild OA degeneration. In our model, OA is caused by altered occlusion from unilateral splints placed for 6 weeks. It was hypothesized that kinematic analysis would identify an overall decrease in joint motion after 6 weeks of splinting.

Materials and Methods

ANIMAL MODEL

Skeletally mature, female, New Zealand white rabbits approximately 1 year old and weighing 5 to 7 kg were purchased from Charles River Laboratories International, Inc (Wilmington, MA). All rabbits were examined by a veterinarian before use in the study and were found to be in good health. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh approved all the animal procedures, which were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of laboratory animals.

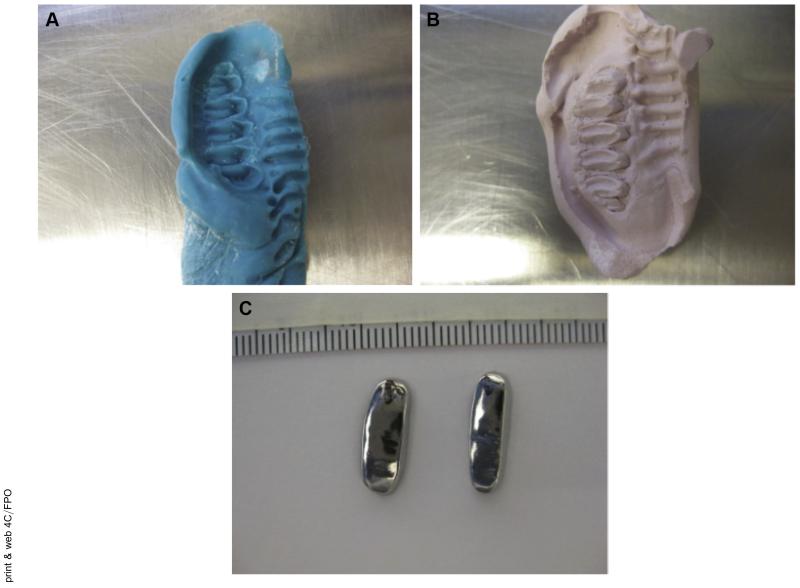

Unilateral dental splints were chosen as the method for altering the occlusion because the splints could be removed at a later point, and the joint space was not penetrated.8-10 For 3 separate procedures (ie, impressions, splint placement, and splint removal), all the rabbits were sedated with ketamine and xylazine, and a surgical plane of anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane. Impressions were taken of the upper and lower right molars of the rabbits to create a unique mold for casting the splints as crowns made from nonprecious metals (Fig 1). The thickness of each casted splint was approximately 1 mm. During a second procedure, the right maxillary and mandibular molar arches were cleaned and primed. Next, the splints were attached to the respective molars with dental cement. Splint placement was verified after 1 week. The splints were removed at 6 weeks, 3 days before the final kinematic data collection. The kinematic data were collected twice, once before the impressions and splint placement and once 6 weeks after splint placement, with the splints removed for 3 days from 3 rabbits (n = 3). After the second kinematic data collection, the rabbits were euthanized, and the whole head was frozen and saved for micro-computed tomography (CT).

FIGURE 1.

Unilateral molar bite raising splints. A, The splints were made by first taking an impression of the molars. B, A plaster mold was made from the impressions. C, The metal splints were cast as crowns on the molds; the superior and inferior views are shown.

Henderson et al. Decreased TMJ Range of Motion in Early OA Rabbit Model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015.

KINEMATICS

Biaxial x-ray systems have been used to assess the impact of injury on the structure-function relationship of the knees and shoulders in humans.11-13 However, it was necessary to determine whether this system could be used for this purpose in the rabbit. Using high-resolution micro-CT, we were able to demonstrate the feasibility of this system for the analysis of rabbit TMJ movements during chewing.14 We determined that rabbit TMJ kinematics were measureable and repeatable, including the maximal distances and movement paths for both the incisors and the condyle-fossa relationship.

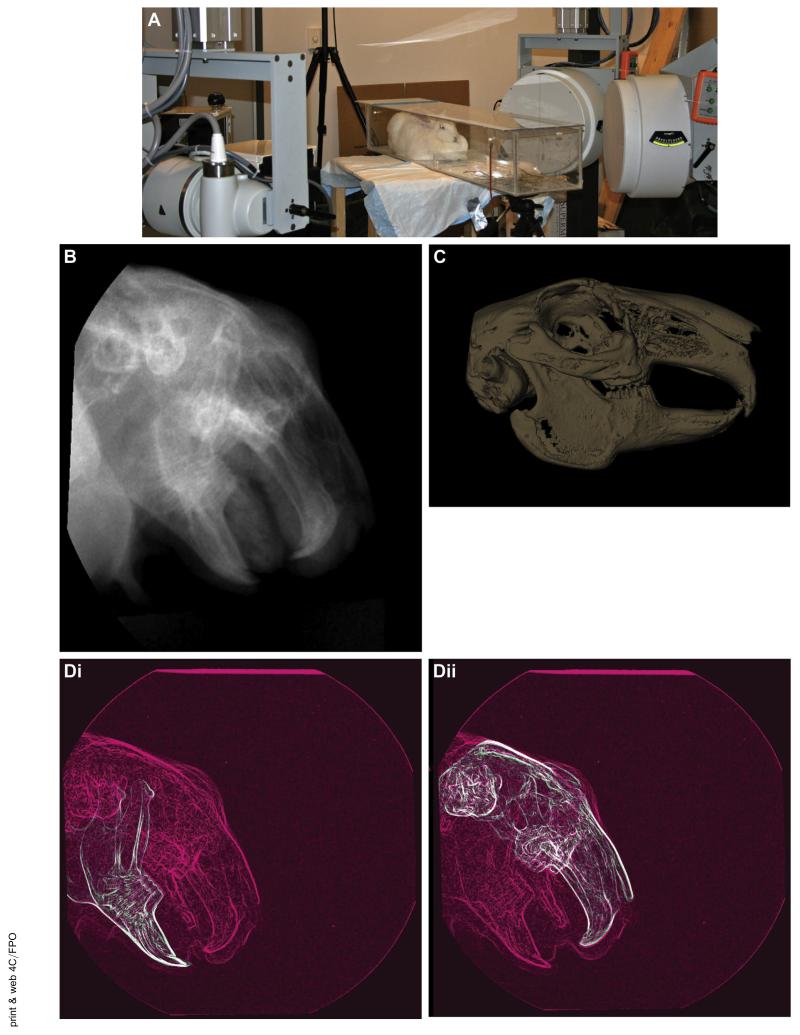

In accordance with these published methods,14 the TMJ kinematics were assessed using a unique high-speed stereoradiographic system consisting of 2 sets of 110-kW pulsed x-ray generators (CPX 3100CV; EMD Technologies, Quebec, QC, Canada), 40-cm image intensifiers (Thales, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) using a 20-cm field of view and high-speed 4-MP digital video cameras (Phantom, version 10; Vision Research, Wayne, NJ). The rabbits were placed in a radiolucent, ventilated cage (Fig 2A) and fed small pieces of dried fruit. Radiographic images were collected at 170 frames/s for 1 s, with 1 ms exposures at a 4-MP image resolution (Fig 2B). At least 3 data acquisitions per rabbit were collected. Three rabbits were tested before splint placement and after 6 weeks of splint placement, with the splints removed 3 days before the second data collection.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of methods for kinematic data collection. A, High-speed biplane radiography was used for image collection. The rabbits were placed in a radiolucent box between 2 sets of x-ray generators and image intensifiers with high-speed cameras. B, Sample radiographic image from the high-resolution cameras at 1 frame in time. C, Three-dimensional (3D) bone model created from a micro-computed tomography (CT) scan of the rabbit head. D, For 2-dimensional to 3D registration, the collected radiographic images (pink) were matched frame by frame with the virtual radiographic images (green) from the CT scan. One of the 2 combined images is shown for Di, each mandible and Dii, the skull. E, 3D distances can be measured. Ei, Vector indicating the distance between the condylar point and the fossa point (C indicates the condyle and F, the fossa; I, inferior; L, lateral; M, medial; and S, superior). Eii, Sample displacement curve.

Henderson et al. Decreased TMJ Range of Motion in Early OA Rabbit Model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015.

The markerless, model-based technique used for determining the 3D kinematics has been extensively described, validated, and tested,11,13-16 including testing the rabbit TMJ.14 In brief, a 3D model of each bone to be tracked was derived from a CT scan (as described in subsequent paragraphs; Fig 2C). A virtual model of the biplane x-ray system was created to generate a pair of digitally reconstructed radiographs (DRRs) using a ray-traced projection through the CT bone model. The bone model was automatically repositioned within the virtual model until a best match was achieved between the simulated DRRs and the actual radiographic image pair (Fig 2D). This technique determined the 3D positions and orientations of the mandible and the skull for each motion frame. After euthanasia, the entire head, including the mandible and skull, was scanned at high resolution (105-μm isotropic voxels) using a micro-CT system (Inveon Micro-CT System; Siemens, Rangos Research Center Animal Imaging Core, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburg Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA). The mandible and skull bones (with teeth) were segmented from each other and from the soft tissue and reconstructed into both surface and volumetric models using Mimics software (Materialise, Inc, Leuven, Belgium; Fig 2C).

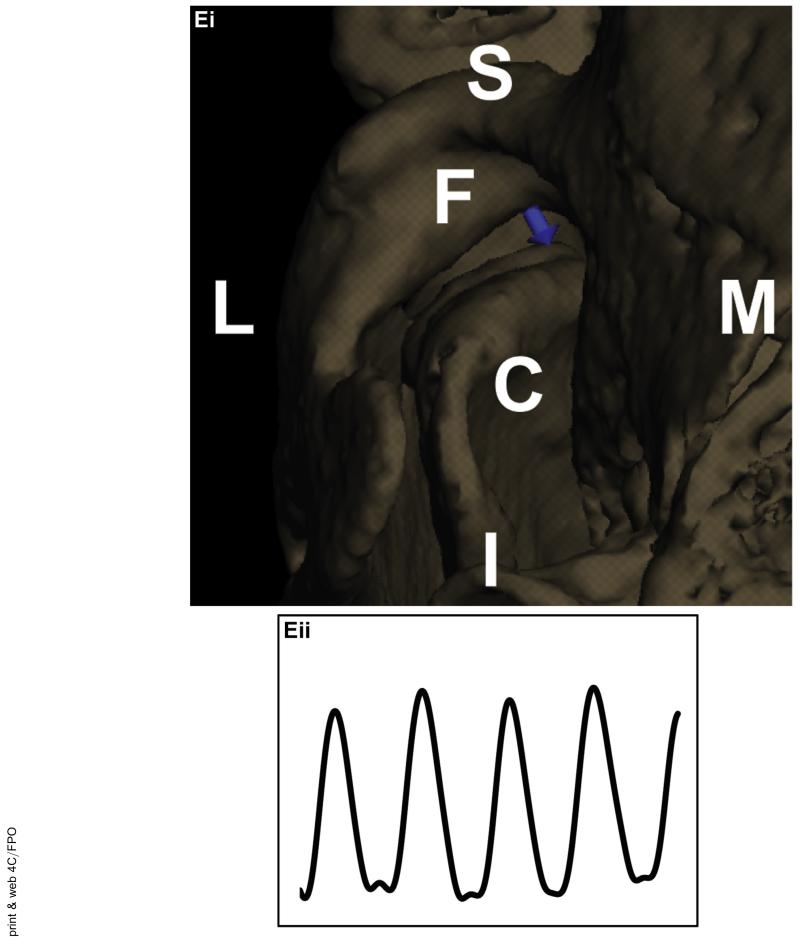

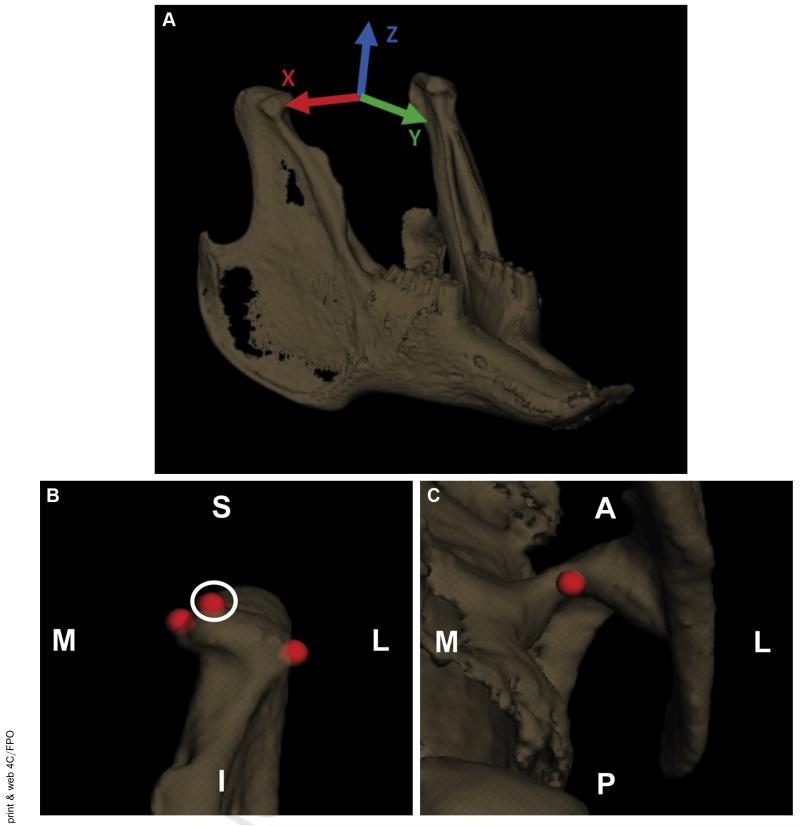

Anatomic coordinate systems similar to the systems used by Brainerd et al17 and in our previous study14 were set up to determine the joint translations and rotations. The transverse (x) axis was aligned through the center of the condyles, the longitudinal (y) axis was parallel to a plane through the occlusal plane, and the vertical (z) axis was the cross product of x and y (Fig 3A).

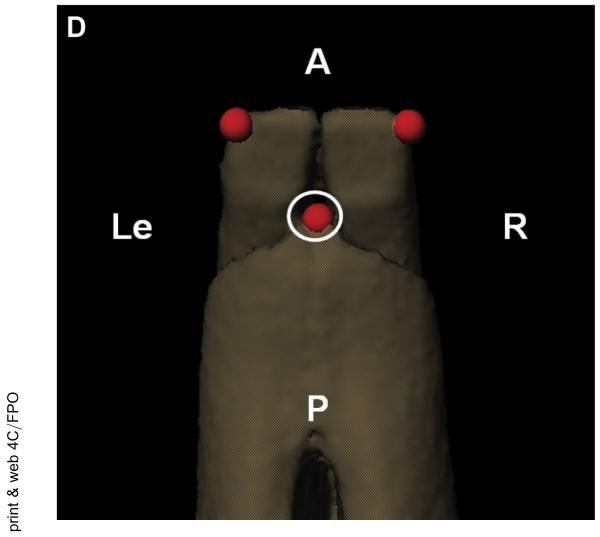

FIGURE 3.

Kinematic analysis tools were used to set up the measurements. A, The anatomic coordinate system for the mandible was set up with the transverse axis (x; red) aligned through the center of the condyles, the longitudinal axis (y; green) parallel to a plane through the occlusal plane (where the teeth meet), and the vertical axis (z; blue) was the cross product of the transverse and longitudinal axes. The skull coordinate system was set up in a similar manner (not shown). B, Condylar measurement point, anterior view of left condyle. C, Fossa measurement point, inferior view of the left fossa. D, Mandible incisor measurement point, superior view. A, anterior; I, inferior; L, lateral; Le, left; M, medial; P, posterior; R, right; S, superior.

Henderson et al. Decreased TMJ Range of Motion in Early OA Rabbit Model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015.

The relative motion of each condyle with respect to the fossa was tracked (Fig 3B,C). The distance between a fixed point on the condyle and a fixed point on the fossa was measured throughout the chewing cycles (Fig 2Ei). The points were placed at the superior most point of the condyle and in the convex region of the fossa. The relative motions of the centers of the 2 points were determined in all 3 anatomic planes. The measurement points were placed in the same location on the condyle and fossa for the pre- and post-splint data collection for each rabbit. The pre- and post-splint motions in each direction and the total magnitude of the vector were analyzed (Fig 2Eii). The movement of the mandible was somewhat elliptical in the coronal plane and always started to the same side during an acquisition. As established in the published data, the side in which the mandible first moves is the working side, and the other is termed the balancing side.18 The condyles were analyzed stratified by the working and balancing condyles, as previously established in the published data.14,18 Of the 3 rabbits, 1 rabbit consistently had the left condyle as the working condyle and 1 rabbit had the right condyle consistently as the working condyle. In the third rabbit, the working condyle switched from the right condyle before splinting to left condyle after splinting. Again, the splint was placed on the right molars.

The relative motion near the incisors was also measured. Because the incisor teeth were observed to grow and change shape from the treatment, they were not directly included in the analysis. To be consistent with the changing incisors from before to after splinting, the incisor markers were placed on the skull and mandible at the center of the incisors at the interface where the teeth met the bone on the posterior side (Fig 3D).

From our previous study,14 some of the rotation-translation relationships were shown to be linear and repeatable; therefore, the slopes of these relationships were also compared. The slope of the movement of the condyles in the superoinferior direction with respect to the transverse rotation during the first 50% of closing was determined for the working and balancing condyles both. The slopes of the paths from the incisal point in the superoinferior direction with respect to the transverse rotation and the incisal point in the anteroposterior direction with respect to the vertical rotation were also determined. Only 1 acquisition was analyzed for each rabbit before and after splinting, if the acquisition had at least 3 complete chewing cycles. All kinematic data were reported as an average ± standard deviation. The data were tested for normality using an Anderson Darling test for normality and found to be normal. Repeated measures analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (P < .05) were used to assess the differences for all kinematic values before and after splinting.

Results

KINEMATIC DATA

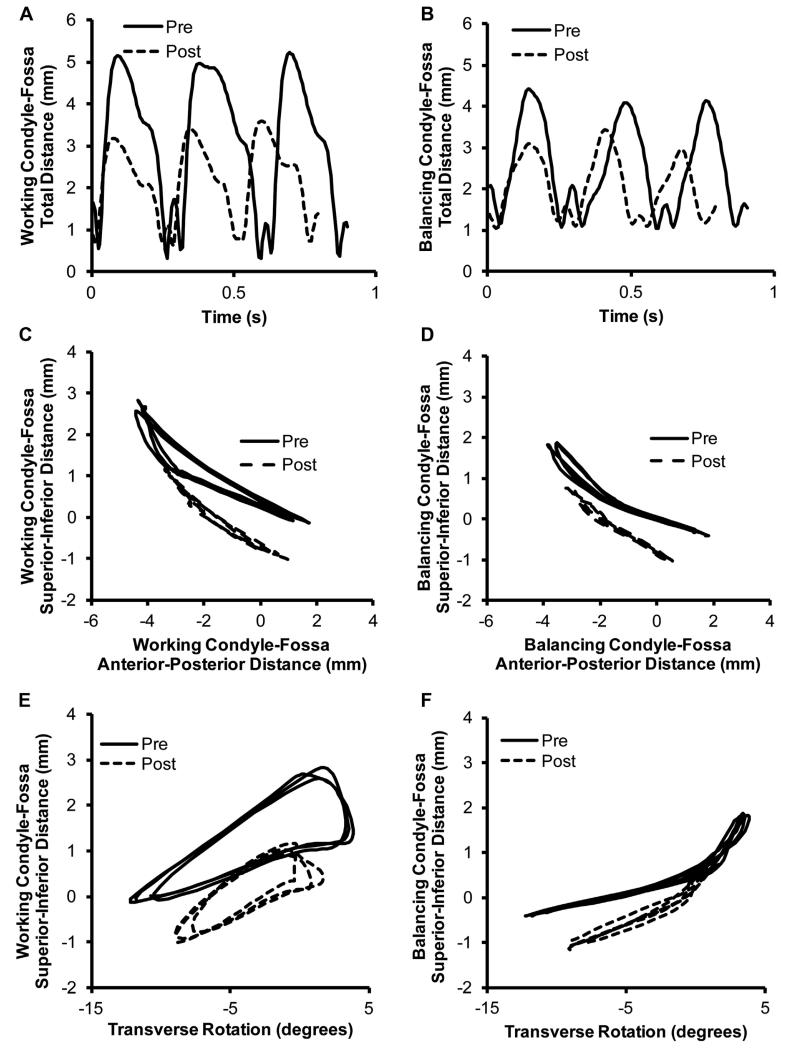

Overall, the altered occlusion from the splint caused the range of motion of the condyles and the teeth to decrease. The distances the condyles traveled on both the working and balancing sides decreased significantly after splinting (Table 1). The total magnitude of the maximum distance between the points on the condyle and fossa decreased by 15.0% for the working condyle and 8.9% for the balancing condyle (P < .05).Figure 4A,B shows the total magnitude of the condyle-fossa distance over time and the decrease in the distance traveled from the splint. Breaking the movement into the vector components, both the anteroposterior displacement and the superoinferior displacement significantly decreased (P < .05). The anteroposterior displacement decreased by 20.5% and the superoinferior by 8.9% for the working condyle. For the balancing condyle, the corresponding displacements decreased by 14.9% and 13.6% (Table 1). Figure 4C,D shows the superoinferior motion with respect to the anteroposterior motion for the working and balancing condyles before and after splinting. The right to left movement of the condyles was minimal and, thus, not reported.

Table 1. KINEMATIC RESULTS FOR RABBITS BEFORE AND AFTER SPLINTING FOR 6 WEEKS (SPLINT REMOVED 3 DAYS BEFORE TESTING).

| Measurement | Before Splinting |

After Splinting |

|---|---|---|

| Working condyle | ||

| AP movement (mm) | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 3 9 ± 0.4* |

| SI movement (mm) | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.2* |

| Magnitude (mm) | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.6* |

| SI movement vs transverse rotation (mm/°) |

0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.04* |

| Balancing condyle | ||

| AP movement (mm) | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.2* |

| SI movement (mm) | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.14* |

| Magnitude (mm) | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.4* |

| SI movement vs transverse rotation (mm/°) |

0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

| Incisors | ||

| AP movement (mm) | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 0.8* |

| SI movement (mm) | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 11.6 ± 1.4* |

| RL movement (mm) | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 6.2 ± 0.5* |

| RL movement vs vertical rotation (mm/°) |

−1.38 ± 0.06 | −1.36 ± 0.09 |

| SI movement vs transverse rotation (mm/°) |

1.12 ± 0.08 | 1.14 ± 0.08* |

Data presented as average ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: AP, anteroposterior; RL, right to left; SI, superoinferior.

Statistically significant (P < .05).

Henderson et al. Decreased TMJ Range of Motion in Early OA Rabbit Model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015.

FIGURE 4.

Condyle–fossa relationships before and after splinting. A, Working and B, balancing side condylar kinematics showing the total condyle–fossa distance with respect to time, before and after splinting. C, Working and D, balancing side condylar kinematics showing the superoinferior condyle–fossa distance with respect to the anteroposterior condyle–fossa distance, before and after splinting. E, Working and F, balancing side condylar kinematics showing the superoinferior condyle–fossa distance with respect to the transverse rotation, before and after splinting. Representative curves from 1 rabbit shown.

Henderson et al. Decreased TMJ Range of Motion in Early OA Rabbit Model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015.

The paths of the condyles were analyzed by determining the slope of the superoinferior distance with respect to the transverse rotation during the first 50% of the closing cycle. The slopes for the working condyle increased significantly by 13.7% after splinting (P < .05; Table 1). The shapes of the curves are shown in Figure 4E,F for the working and balancing condyles, respectively.

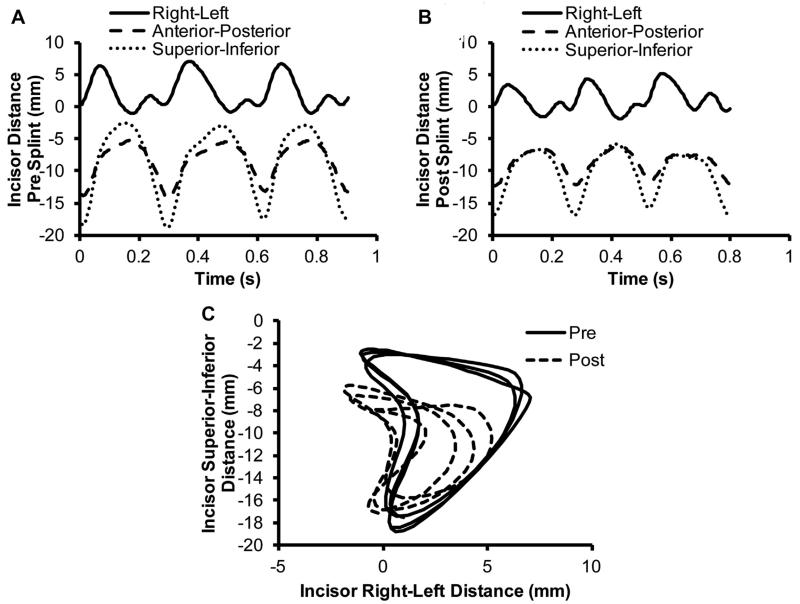

The distances the incisors traveled also decreased significantly after splinting (P < .05; Table 1). The right to left movement decreased by 11.2%. The anteroposterior movement decreased by 16.1%. The superoinferior movement decreased by 13.0%. The shapes of the curves are shown in Figure 5A,B. Figure 5C shows the change in movement from before to after splinting in the coronal plane.

FIGURE 5.

Patterns of incisor movement before and after splinting. The change in the distance of the mandible incisors from the skull incisors with relation to the time A, before splinting and B, after splinting. C, Relationship of the mandible incisors to the skull incisors in the coronal plane before and after splinting. Three chewing cycles are shown in each graph. Representative curves from 1 rabbit shown.

Henderson et al. Decreased TMJ Range of Motion in Early OA Rabbit Model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015.

Videos 1 to 4 illustrate the chewing pattern of a rabbit before and after splinting (supplementary online information).

Discussion

An overall decrease in the range of joint motion at both the condyles and the incisors was observed after placement of the dental splints for 6 weeks. The persistent change in kinematics likely resulted from the abnormal occlusion and degeneration of the condylar fibrocartilage observed in our previous studies.7,19 The kinematics of the rabbit TMJ at the condyles and the incisors were easily measured using our noninvasive system before and after splint placement to determine the changes in the joint movement. The decreased range in incisal movement after splinting was comparable to a previous TMJ disc injury study.20 However, the specific values could not be compared owing to the different measurement techniques. The presplint control incisal data were also consistent with the findings of our previous study and with the data from other normal rabbit kinematic studies.14,18,20,21

Determining the changes in condylar movement might lead to a better understanding of early movement predictors in the development of TMJDs. This knowledge of dynamic TMJ function through 3D skeletal kinematics is essential for investigating the effects of injury or disease in the TMJ. The altered occlusion model used in the present study has been shown to produce condylar fibrocartilage degeneration that would likely not be detected using conventional magnetic resonance imaging.7,19 Understanding the changes in joint movement that occur from various types of TMJDs could allow for earlier diagnosis and treatment; for example, if a certain signature of changes in movement are observed earlier before the onset of severe joint degeneration. As such, our findings suggest that decreases in 20% anteroposterior displacement of the working condyle might be indicative of condylar degeneration and early-stage TMJ-OA.

One limitation of the present study was that only 1 micro-CT scan could be obtained per rabbit head after the final time point. Ideally, a micro-CT scan would be collected for each point that the kinematic data were collected. This would also allow for analysis of the effect of the splints on the bony structure. However, owing to the size limitations of the scanner, the heads could only be scanned after euthanasia and decapitation. With only 1 scan, it was assumed that the bony structures of the joints were not affected by the treatment. Another assumption of our study was that the bony structure of the skull and mandible were rigid. However, it has been shown that the mandible can deform during joint motion,22,23 which led to some minor errors in the DDR matching process. For a few frames in each chew cycle, the mandible and fossa were barely touching along the edges of both condyles. Rabbits’ teeth are also constantly erupting; thus, the teeth were ignored throughout the analysis. In future studies with longer measurement points, the teeth might need to be filed down to their original height. The possible changes in muscle performance were also not considered in the present study. Even with these limitations, our study has provided an important initial understanding of what can change in the TMJ motion from inducing TMJ-OA with altered occlusion.

In conclusion, the splint model used in the present study was advantageous, because it allowed for removal of the splints, and the joint space was not penetrated. Future work should consider the various lengths of time between splint placement and removal and allow time for recovery to understand whether and when the change in joint movement has the potential to correct itself and the joint to heal or when the TMJ-OA becomes chronic and permanent. The potential exists with this type of TMJD animal model to combine the kinematic analysis with other assessments such as pain measurements and mechanical assessments of the TMJ tissues, which will allow for multidisciplinary studies of various types of TMJDs. The combination of assessment methods will allow for a fuller understanding of the TMJ disease progression in this and other animal models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Robert Mortimer for help with the rabbit kinematic data collection.

The present study received funding from the National Science Foundation (grant 0812348), the National Institutes of Health (grant T32 EB003392), the University of Pittsburgh Research Fund, and the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine.

References

- 1.Gray RJM, Davies SJ, Quayle AA. Temporomandibular Disorders: A Clinical Approach. British Dental Association; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solberg WK. Epidemiology, incidence and prevalence of temporomandibular disorders: A review. In: Laskin D, Greenfield W, Gale E, editors. Diagnosis and Management of Temporomandibular Disorders. American Dental Association; Chicago, IL: 1983. p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mejersjo C, Hollender L. Radiography of the temporomandibular joint in female patients with TMJ pain or dysfunction: A seven year follow-up. Acta Radiol. 1984;25:169. doi: 10.1177/028418518402500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ware WH. Clinical presentation. In: Helms CA, Katzberg RW, Dolwick MF, editors. Internal Derangements of the Temporomandibular Joint. Radiology Research and Education Foundation; San Francisco, CA: 1983. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagger RG, Bates JF, Kopp S. Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction: Essentials. Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarb GA, Carlsson GE. Temporomandibular disorders: Osteoarthritis. J Orofac Pain. 1999;13:295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson SE, Lowe JR, Tudares MA, et al. Temporomandibular joint fibrocartilage degeneration from unilateral dental splints. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:1. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw RM, Molyneux GS. The effects of induced dental malocclusion on the fibrocartilage disc of the adult rabbit temporomandibular joint. Arch Oral Biol. 1993;38:415. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(93)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sergl HG, Farmand M. Experiments with unilateral bite planes in rabbits. Angle Orthod. 1975;45:108. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1975)045<0108:EWUBPI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaves K, Munerato MC, Ligocki A, et al. Microscopic analysis of the temporomandibular joint in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) using an occlusal interference. Cranio. 2002;20:116. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2002.11746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bey MJ, Zauel R, Brock SK, Tashman S. Validation of a new model-based tracking technique for measuring three-dimensional, in vivo glenohumeral joint kinematics. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128:604. doi: 10.1115/1.2206199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bey MJ, Kline SK, Tashman S, Zauel R. Accuracy of biplane x-ray imaging combined with model-based tracking for measuring in-vivo patellofemoral joint motion. J Orthop Surg Res. 2008;3:38. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashman S, Kolowich P, Collon D, et al. Dynamic function of the ACL-reconstructed knee during running. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;454:66. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802bab3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson SE, Desai R, Tashman S, Almarza AJ. Functional analysis of the rabbit temporomandibular joint using dynamic biplane imaging. J Biomech. 2014;47:1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tashman S, Anderst WJ. In-vivo measurement of dynamic joint motion using high speed biplane radiography and CT: Application to canine ACL deficiency. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:238. doi: 10.1115/1.1559896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig M, Bir C, Viano D, Tashman S. Biomechanical response of the human mandible to impacts of the chin. J Biomech. 2008;41:2972. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brainerd EL, Baier DB, Gatesy SM, et al. X-ray reconstruction of moving morphology (XROMM): Precision, accuracy and applications in comparative biomechanics research. J Exp Zool. 2010;313A:262. doi: 10.1002/jez.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morita T, Fujiwara T, Negoro T, et al. Movement of the mandibular condyle and activity of the masseter and lateral pterygoid muscles during masticatory-like jaw movements induced by electrical stimulation of the cortical masticatory area of rabbits. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:462. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson SE, Tudares MA, Gold MS, Almarza AJ. Analysis of pain in the rabbit temporomandibular joint after unilateral splint placement. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1371. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tominaga K, Yamada Y, Fukuda J. Changes in chewing pattern after surgically induced disc displacement in the rabbit temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:400. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90923-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huff KD, Asaka Y, Griffin AL, et al. Differential mastication kinematics of the rabbit in response to food and water: Implications for conditioned movement. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2004;39:16. doi: 10.1007/BF02734253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen DC, Lai YL, Chi LY, Lee SY. Contributing factors of mandibular deformation during mouth opening. J Dent. 2000;28:583. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Sukhun J, Helenius M, Lindqvist C, Kelleway J. Biomechanics of the mandible. Part I: Measurement of mandibular functional deformation using custom-fabricated displacement transducers. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1015. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.