Abstract

Signal transduction of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is regulated by various feedback mechanisms. Given the greater molar ratio between Raf-MEK than between MEK-ERK in cells, it may be possible that MEK1/2 levels are regulated to modulate Raf/MEK/ERK activity upon pathway stimulation. Nevertheless, it has not been reported whether MEK1/2 expression can be subject to a feedback regulation. Here, we report that the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway can feedback-regulate cellular MEK1 and MEK2 levels. In different cell types, ΔRaf-1:ER- or B-RafV600E-mediated MEK/ERK activation increased MEK1 but decreased MEK2 levels. These regulations were abrogated by ERK1/2 knockdown mediated by RNA interference, suggesting the presence of a feedback mechanism that regulates MEK1/2 levels. Subsequently, analyses using qPCR and luciferase reporters of the DNA promoter and 3′ untranslated region revealed that the feedback MEK1upregulation was in part attributed to increased transcription. However, the feedback MEK2 downregulation was only observed at protein levels, which was blocked by the proteasome inhibitors, MG132 and bortezomib, suggesting that the MEK2 regulation is mediated at a post-translational level. These results suggest that the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway can feedback-regulate cellular levels of MEK1 and MEK2, wherein MEK1 levels are upregulated at transcriptional level whereas MEK2 levels are downregulated at posttranslational level.

Keywords: Raf, MEK1, MEK2, ERK1/2, feedback regulation

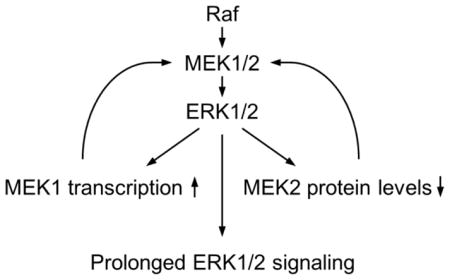

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK/MAPKK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK/MAPK) pathway has a critical role in coordinating cell survival, cell cycle progression and differentiation in response to various signals from different receptor tyrosine kinases and other cell surface receptors [reviewed in [1]]. The biological significance of Raf/MEK/ERK signaling spans from early development to various diseases. Especially in cancers, deregulated Raf/MEK/ERK signaling is a central signature and a key therapeutic target in many epithelial cancers [reviewed in [2–4]]. The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is a highly specific three-layered kinase cascade that consists of the Ser/Thr kinase Raf (i.e., A-Raf, B-Raf, or C-Raf/Raf-1), the highly homologous dual-specificity kinases MEK1/MAPKK1 and MEK2/MAPKK2 (collectively referred to MEK1/2), and the ubiquitously expressed Ser/Thr kinase ERK1/MAPK3 and its homologue ERK2/MAPK1 (collectively referred to ERK1/2). Upon activation, Raf mediates phosphorylation of MEK1 and MEK2 at two Ser residues (i.e., Ser217/221 for MEK1 and Ser222/226 for MEK2), which in turn phosphorylate ERK1 and ERK2 on Thr202/Tyr204 and Thr183/Tyr185, respectively.

Given its pivotal roles for various cell physiological aspects, precise control of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is critical and understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying its regulation is important. Raf/MEK/ERK signaling is coordinated by a complex network of regulators, including the small GTPases Ras and Rap, phosphatases, scaffolds, and other kinases, which affects the magnitude, duration, and compartmentalization of the pathway activity [5–8]. Of note, the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is subject to various feedback regulations which are triggered at a later stage of pathway stimulation under different cell physiological conditions. Most of the feedback mechanisms identified to date are regulated via ERK1/2-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of its upstream regulators. For example, ERK1/2 can phosphorylate MEK1 on Thr292 and Thr386 to downregulate MEK1 activity [9, 10]. ERK1/2 can also phosphorylate multiple sites on Raf-1 to inhibit its interaction with Ras [11], and Thr753 of B-Raf to promote disassembly of B-Raf/Raf-1 heterodimers [12]. In addition, ERK1/2 can phosphorylate Son of Sevenless, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor of Ras, to regulate its interaction with the adaptor protein Grb2, which subsequently affects the rate of Ras-mediated receptor tyrosine kinase signaling toward Raf/MEK/ERK [13]. However, there have been no reports whether MEK1/2 expression can be subject to a feedback regulation.

Previously, we reported that depletion of mortalin, a molecular chaperone of the heat shock protein 70 family, can induce growth arrest in different cancer cell lines harboring B-RafV600E by upregulating MEK/ERK activity, which subsequently induces expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1 [14]. Intriguingly, this upregulation of MEK/ERK activity was correlated with altered MEK1/2 levels. While investigating the underlying mechanisms, we found that cellular MEK1/2 levels can be regulated by ERK1/2-mediated feedback mechanisms. In this report, we demonstrate that Raf/MEK/ERK can feedback-upregulate MEK1 at transcriptional level whereas feedback-downregulate MEK2 at a posttranslational level sensitive to the proteasome activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture, generation of stable lines, and reagents

The human prostate cancer line, LNCaP (ATCC, Manassas, VA), was maintained in phenol red-deficient RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. The E1A-immortalized normal human fibroblasts IMR90 (IMR90E1A) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% non-essential amino acids. The human melanoma lines, SK-MEL 2 (ATCC), SK-MEL 28 (ATCC) and A375 (ATCC), were maintained in minimal essential medium (Invitrogen) and Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium, respectively. These media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. The LNCaP and TT lines stably expressing ΔRaf-1:ER (LNCaP-Raf:ER and TT-Raf:ER, respectively) were previously described [15]. IMR90E1A cells stably expressing ΔRaf-1:ER (IMR90E1A-Raf:ER) were generated by stably infecting IMR90E1A cells with lentiviral pHAGE-Raf:ER. ΔRaf-1:ER was activated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cell proliferation was measured by the colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) assay, as previously described [15]. Other chemicals used are actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich), MG-132 (Sigma-Aldrich), cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich), polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich), bortezomib (Selleck Chemicals, Houston), PLX4032 (Selleck Chemicals), AZD6244 (Selleck Chemicals), and SCH772984 (ChemieTek, Indianapolis, IN).

2.2. Lentiviral small hairpin RNA (shRNA) and gene expression constructs

The lentiviral pLL3.7-shRNA vector targeting GGCGAUAUGAUGAUCCUGAA of human mortalin RNA (shMort) was previously described [14]. The pLL3.7-shRNA vectors targeting GACCUGAAUUGUAUCAUC of human ERK1 RNA (shERK1) and CCAAAGCUCUGGACUUAUU of human ERK2 RNA (shERK2) were previously described [15]. The pLL3.7-shRNA vectors targeting GCAACUCAUGGUUCAUGCU of human MEK1 RNA (shMEK1) and GAAGGAGAGCCUCACAGCA of human MEK2 RNA (shMEK2) were previously described [16]. The lentiviral pGIPZ-shRNA vectors targeting three different regions (CCUGUCAAUAUUGAUGACUUG, GCAGAUGAAGAUCAUCGAAAU, and GGUGUGGAAUAUCAAACAAAU) of human B-Raf RNA were previously described [17]. Specific knockdown of target proteins was confirmed by Western blot analysis. Generation of the lentiviral pHAGE vectors overexpressing the human ERK1 mutant harboring Lys71Arg/Thr202Ala/Tyr204Phe (ERK1DN), B-RafV600E, or ΔRaf-1:ER was previously described [15, 18]. Lentivirus was produced by co-transfecting 293T cells with the lentiviral expression vector and packaging vectors, as previously described (8). The resulting supernatant was collected after 48–72 h. For infection, lentiviral supernatant was mixed with polybrene at 8 μg/ml. Viral titers were determined by infecting recipient cells with serially diluted viral supernatants and scoring cells expressing GFP at 48 h post-infection. Cells were switched into fresh culture medium on the following day of infection.

2.3. Luciferase reporters of MEK1 promoter and 3′ untranslated region (UTR)

To generate the MEK1 promoter-luciferase reporters harboring 839 (−713 to +126) and 668 (−713 to −45) base pairs of human MEK1 promoter DNA, genomic DNA of TT cells were amplified by PCR using the forward primer CGAGTGCCTGTAATCCCAGCTA and the reverse primers ACCAGAGCCCAGCTCCA and CCTATTGCCTCGCAGACAACCA. Obtained DNA fragments were ligated to XhoI/KpnI sites of pGL2basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI). To generate 3′UTR reporter system of MEK1, entire MEK1 3′UTR was amplified using CCCATGCTTCTAGAGTCTAAGTGTTTGGGAAGCA and TATTAGAACTCGAGATTAGATTTGTTAAACATC. Obtained DNA fragment was ligated to XhoI/XbaI sites of pLightSwitch 3′ UTR reporter vector (SwitchGear Genomics, Carlsbard, CA).

For luciferase assay, LNCaP-Raf:ER cells were transfected with the promoter or 3′UTR reporters using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) or GeneExpresso8000 (Excellgen, Rockville, MD) in triplicate in 24-well plates for 16 hours prior to 48 hour tamoxifen treatment. Cells were harvested and analyzed using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) for promoter reporter activity or the LightSwitch Luciferase assay reagent (SwitchGear Genomics) for 3′UTR reporter activity, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

qPCR was performed by reverse transcription of 0.25 μg total RNA and subsequent polymerase chain reaction using the Mx3005PTM instrument (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and Brilliant SYBRR® Green QPCR Core Reagent Kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Thermocycling conditions were 10 min at 95°C as first denaturation step, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 60 seconds and 72°C for 30 seconds. For normalization, expression of β-actin/ACTB was measured. Primers used are CAGAAGAAGCTGGAGGAGCTAG and CCATCGCTGTAGAACGCACCAT (MEK1, 574–885), CGAGGCAAACCTGGTGGACCT and CCGTAGAAGCCCACGATGTAC (MEK2, 343–658), CCGACCAGCAGATGAAGATCAT and TCAACATTTTCACTGCCACATCAC (B-Raf 1,098–1,516), TCAGACTCCAAAGCCCTTGACCT and AAGCGTGCTGTCTCCTGGAAGAT (ERK1, 994–1212), ATGCTGACTCCAAAGCTCTGGACT and TCTGAGCCCTTGTCCTGACAAATT (ERK2, 1,081–1,346), CTGGAGACTCTCAGGGTCGAA and CCAGCACTCTTAGGAACCTCTCA (p21CIP1, 526–844), and GTCCTCTCCCAAGTCCACAC and GGGAGACCAAAAGCCTTCAT (ACTB 1,543–1,731). Amplified gene copy numbers was calculated by the delta-delta-Ct method [19].

2.5. Immunoblot analysis

Cells harvested at various times were lysed in 62.5 mM Tris (pH 6.8)-2% SDS mixed with the protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) that contains 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride, pepstatin A, E-64, bestatin, leupeptin, and aprotinin, and briefly sonicated before determining protein concentration using the BCA reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). 50 μg of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and stained with Fast Green reagent (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Membrane filters were then blocked in 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5)-0.9% NaCl-0.05% Tween 20 with 5% nonfat dry milk, and incubated with appropriate antibodies. Antibodies were diluted as follows: phospho-MEK1/2 (Ser217/221 for MEK1 and Ser222/226 for MEK2), 1:2,500; MEK1, 1:1,000; MEK2, 1:1,000; p21CIP1, 1:1,000 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA); phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204 for ERK1 and Thr183/Tyr185 for ERK2), 1:2,500; ERK1/2, 1:2,500; phospho-p90RSK (Thr359/Ser363), 1:2,500; glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 1:5,000 (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA); cyclin D1, 1:1,000 (Sigma-Aldrich). The Supersignal West Pico and Femto chemiluminescence kits (Pierce) were used for visualization of the signal. Images of immunoblots were taken and processed using ChemiDoc XRS+ and Image Lab 3.0 (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Student’s t-Test (paired two sample for means) and Analysis of variance (ANOVA, single factor) were used to assess the statistical significance of two data sets and multiple groups, respectively. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) was calculated for time- or dose-dependent analyses. Pearson’s r equal to 0.70 or higher, or equal to −0.70 or lower, was considered to indicate very strong positive, or negative, relationship.

3. Results

3.1. ERK1/2 activity is necessary for mortalin depletion to induce MEK1 upregulation in B-RafV600E-transformed cancer cells

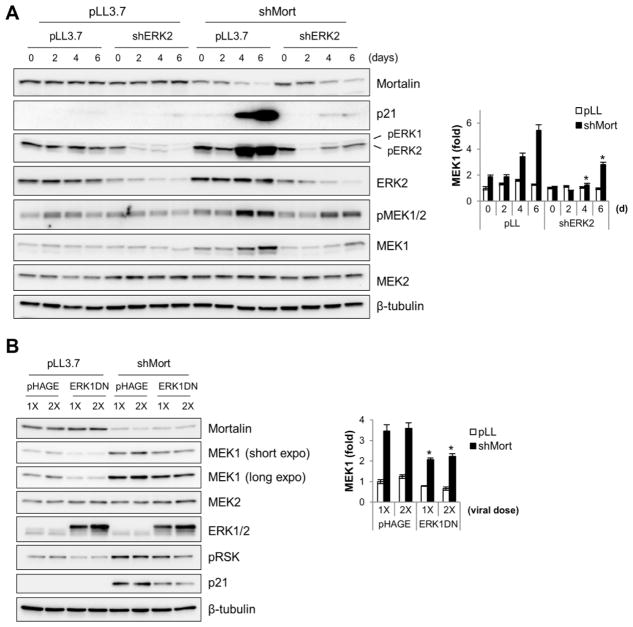

To investigate the mechanism by which mortalin regulates MEK/ERK activity in B-RafV600E-transformed cancer cells, we depleted mortalin in the human melanoma cell line, SK-MEL 28, using a lentiviral shRNA construct (shMort) which we previously validated for its specificity [14]. Consistent with our previous observation, when mortalin was depleted to a level sufficient to induce p21CIP1 expression, cells exhibited upregulated MEK/ERK activity, as determined by Western blot analysis of phosphorylations of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 on their activation segments (Fig. 1A). Along with these changes, gradually increasing Western blot signals of MEK1, but not MEK2, were detected in this time-course study (Fig. 1A). Under this condition, as we previously demonstrated [14], ERK1/2 phosphorylation occurred with ERK2 phosphorylation being predominant over ERK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1A). Intriguingly, when ERK2 was depleted by RNA interference to a level sufficient to block shMort-induced p21CIP1 expression, shMort-induced MEK1 upregulation was also significantly attenuated in these cells (Fig. 1A). Similarly, when a dominant-negative ERK1 (ERK1DN) was overexpressed at a level sufficient to substantially block shMort-mediated p21CIP1 expression and phosphorylation of p90RSK1, a bona fide ERK1/2 substrate [20], it also effectively suppressed shMort-induced MEK1 upregulation in this cell line (Fig. 1B). However, in contrast, MEK2 levels were not significantly affected under these conditions. These data suggest that mortalin depletion increases MEK1 levels in B-RafV600E-transformed cancer cells and that this increase requires upregulation of MEK/ERK activity induced by mortalin depletion.

Figure 1. Mortalin knockdown upregulates MEK1 levels by increasing MEK/ERK activity in B-RafV600E-transformed cancer cells.

(A) SK-MEL 28 cells were co-infected with pLL3.7 viruses expressing shRNAs that target mortalin mRNA (shMort) or ERK2 mRNA (shERK2) for indicated periods. Total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for expression of mortalin, p21CIP1, phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), ERK2, phosphorylated MEK1/2 (pMEK1/2), MEK1, MEK2, and β-tubulin. The right panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 signals. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05 for shERK2 effects on shMort-induced MEK1 fold changes (Student’s t test). (B) Western blot analysis of total lysates of SK-MEL 28 cells co-infected with shMort and two different doses of pHAGE virus expressing dominant-negative ERK1-K71R/T202A/Y204F (ERK1DN) for 5 days. pRSK denotes phosphorylated p90RSK1. The right panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 signals. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05 for shERK1DN effects on shMort-induced MEK1 fold changes (Student’s t test).

3.2. Basal MEK1 levels in B-RafV600E- or N-RasQ61R-transformed cancer cells are regulated by MEK/ERK activity

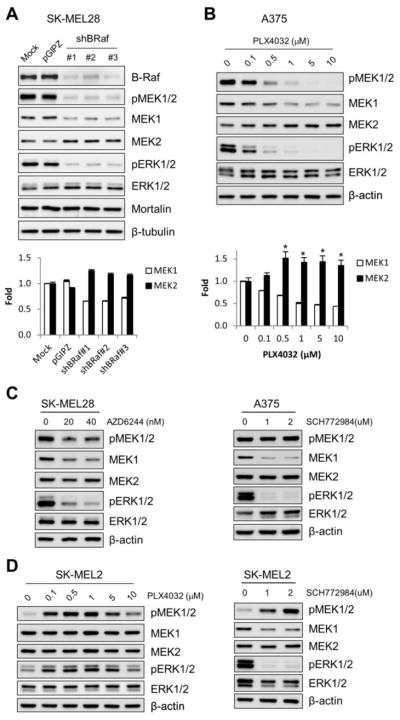

Given the requirement of MEK/ERK activity in the upregulation of cellular MEK1 levels upon mortalin depletion, we determined whether depletion of Raf/MEK/ERK activity would affect basal MEK1/2 levels in an opposite manner to mortalin depletion in SK-MEL 28 cells. In an analysis using three different B-Raf-specific lentiviral shRNA constructs, B-RafV600E knockdown consistently reduced phosphorylation levels of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 in SK-MEL 28 cells (Fig. 2A). Under these conditions, significantly reduced MEK1 protein levels were detected whereas MEK2 protein levels were mildly upregulated (Fig. 2A). B-RafV600E knockdown however did not affect mortalin levels in SK-MEL 28 cells, suggesting that its effects on MEK1/2 levels were independent of mortalin (Fig. 2A). This is in agreement with our previous characterization of B-Raf and mortalin as independent regulators of MEK/ERK [14]. Consistent with this observation in SK-MEL 28 cells, we found that the B-RafV600E specific inhibitor, PLX4032, could downregulate MEK1 levels and upregulate MEK2 levels in another B-RafV600E-transformed cancer cell line, A375, when the cells were treated with the inhibitor at a dose that effectively depleted MEK/ERK activity (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. MEK1/2 levels are sensitive to B-Raf activity in B-RafV600E-transformed cancer cells.

(A) SK-MEL 28 cells were infected for 5 days with pGIPZ viruses expressing three different shRNAs that target B-Raf mRNA (shBRaf). Uninfected (mock) or the empty pGIPZ virus-infected cells were used for comparison. Total cell lysates were analyzed for expression of the indicated proteins by Western blotting. The bottom panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 and MEK2 signals. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. P < 0.005 for the effects of each shBRaf construct on MEK1 and MEK2 (ANOVA). (B) Western blot analysis of total lysates of A375 cells treated with increasing doses of PLX4032 for 24 hours. The bottom panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 and MEK2 signals in the bottom panel. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. Pearson’s r = −0.707 for MEK1. *p < 0.05 relative to 0 μM PLX4032 (Student’s t test). (C) Western blot analysis of total lysates of SK-MEL 28 and A375 cells treated with AZD6244 or SCH772984 for 24 hours. (D) Western blot analysis of total lysates of SK-MEL 2 cells treated with PLX4032 or SCH772984 for 24 hours.

Consistent with these data, the MEK1/2 specific inhibitor, AZD6244, and the ERK1/2 specific inhibitor, SCH772984, also downregulated MEK1 levels in SK-MEL 28 and A375 cells (Fig. 2C). However, these inhibitors did not significantly affect MEK2 levels in these B-RafV600E tumor cells (Fig. 2C). Of note, in the N-RasQ61R-transformed SK-MEL 2 cells, PLX4032 did not affect MEK1/2 levels (Fig. 2D, left panel). Contrary to its effects in the B-RafV600E tumor cells, PLX4032 increased phosphorylation levels of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 in SK-MEL 2 cells (Fig. 2D, left panel). This paradoxical activation of MEK/ERK by B-Raf inhibitors in N-Ras tumor cells have been previously reported [21]. However, consistent with its effects in the B-RafV600E tumor cells, SCH772984 downregulated MEK1 levels in SK-MEL 2 cells although it did not affect MEK2 levels (Fig. 2D, right panel). These data suggest that basal levels of MEK1/2, especially MEK1, are sensitive to Raf/MEK/ERK activity in Raf- or Ras-transformed cancer cells.

3.3. Raf activation can upregulate MEK1 levels while downregulating MEK2 levels in an ERK1/2-dependent manner in non-Ras/Raf transformed cells

The findings above strongly indicated the presence of a mechanism(s) which regulates MEK1 and MEK2 levels in response to Raf/MEK/ERK activation. To further evaluate this possibility, we determined whether Raf activation could affect MEK1/2 levels in different cell types in which Raf/MEK/ERK signaling is not deregulated and, if so, whether the changes could be inhibited by ERK1/2 depletion. This question was addressed using the E1A-immortalized normal fibroblasts, IMR90E1A, and the tumor cell lines LNCaP and TT cells, which were previously shown to maintain much lower basal Raf/MEK/ERK activity than primary normal fibroblasts [15].

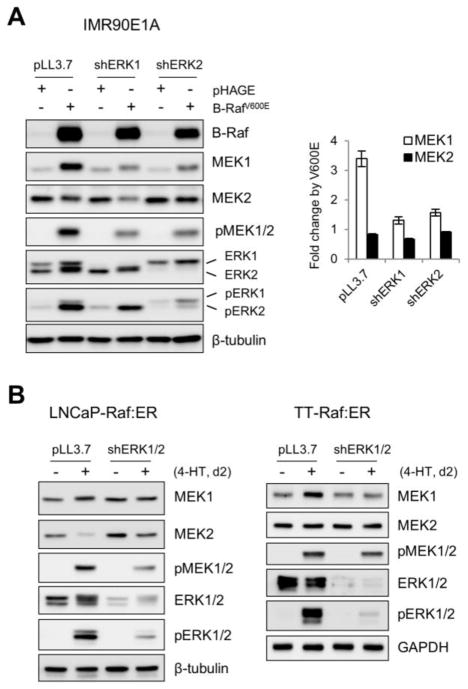

When the MEK/ERK pathway was activated in IMR90E1A using B-RafV600E and in LNCaP and TT cells using tamoxifen-inducible ΔRaf-1:ER, a CR3 catalytic domain of Raf-1 fused to hormone binding domain of the estrogen receptor [22], phosphorylation levels of MEK1/2 were significantly increased (Fig. 3A and 3B). Under this condition, we found that MEK1 protein levels were also increased in these cells. However in contrast, Raf activation mildly decreased MEK2 protein levels in IMR90E1A and LNCaP cells, albeit not in TT cells (Fig. 3A and 3B). The ΔRaf-1:ER-induced effects were specific to Raf activity because 4-hydroxytamoxifen alone did not induce any similar effects (Fig. 3B). These Raf-induced effects on MEK1/2 levels are consistent with the effects of B-RafV600E knockdown or inhibition in the B-RafV600E-transformed tumor cells.

Figure 3. Depletion of ERK1/2 by RNA interference blocks B-RafV600E- or Raf:ER-induced MEK1 upregulation and MEK2 downregulation in non-Raf-transformed cells.

(A) IMR90E1A cells, infected with pLL3.7 viruses expressing shRNA that targets mRNA of ERK1 (shERK1) or ERK2 (shERK2) for 4 days, were infected with pHAGE-B-RafV600E virus for 2 days. pHAGE is the control empty virus. Total cell lysates were analyzed for expression of the indicated proteins by Western blotting. The right panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 and MEK2 signals. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. P < 0.005 for MEK1 (ANOVA). (B) LNCaP-Raf:ER and TT-Raf:ER cells, co-infected with lentiviral shERK1 and shERK2 (shERK1/2), were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-HT) for 2 days. Total cell lysates were analyzed for expression of the indicated proteins by Western blotting.

In these cells, Raf regulated MEK1/2 levels in a ERK1/2-dependent manner. Knockdown of ERK1 or ERK2 consistently attenuated B-RafV600E–induced MEK1 upregulation in IMR90E1A cells, whereas knockdown of ERK2, but not ERK1, was sufficient to suppress B-RafV600E–induced MEK2 downregulation in IMR90E1A (Fig. 3A). Moreover, knockdown of both ERK1 and ERK2 effectively suppressed ΔRaf-1:ER-induced MEK1 upregulation in TT cells and ΔRaf-1:ER-induced MEK2 downregulation in LNCaP cells (Fig. 3B). However, the effect of ERK1/2 depletion on ΔRaf-1:ER-induced MEK1 upregulation in LNCaP cells was indeterminable because ERK1/2 depletion highly upregulated basal MEK1 levels. These data strongly suggest that Raf can regulate MEK1/2 levels via ERK1/2-mediated feedback mechanisms.

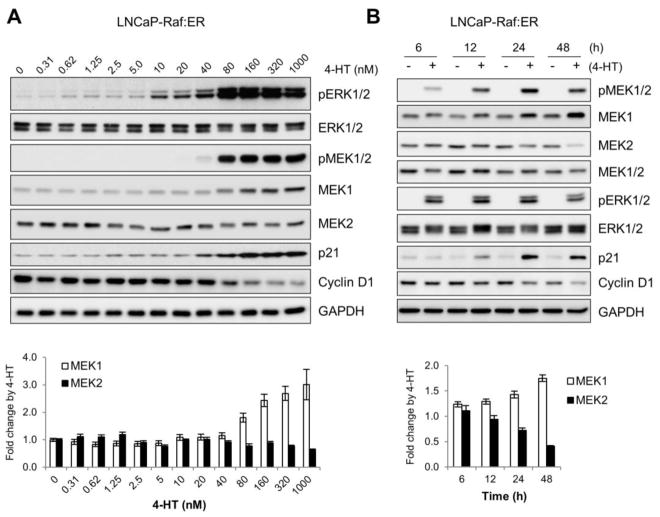

3.4. Raf/MEK/ERK regulates MEK1 and MEK2 levels in a manner dependent upon its signaling intensity and duration

Because the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is known to mediate different, even opposing, contexts of signaling depending upon the magnitude and duration of its activation [6, 7], we examined the effects of different magnitude and duration of Raf/MEK/ERK activation on MEK1/2 levels. When ΔRaf-1:ER was activated using serially increasing doses of tamoxifen in LNCaP cells, induction of MEK1 upregulation was commensurate with the intensity of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). These changes were accompanied by concurrent p21CIP1 induction and cyclin D1 downregulation, the markers for the onset of growth arrest signaling (Fig. 4A). However, MEK2 downregulation was only mild under this condition. When a time-course study was conducted, Raf-induced MEK1 upregulation and MEK2 downregulation became prominent at around 24 to 48 hours after Raf activation in LNCaP cells, which was concurrent with p21CIP1 induction and downregulation of cyclin D1 (Fig. 4B). Of note, when these cell lysates were analyzed using an antibody specific to both MEK1 and MEK2, the corresponding Western blot signals at different time-points did not show as significant difference, which may account for the nearly even levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation throughout the time periods (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that higher magnitude of Raf/MEK/ERK activity is associated with a temporal regulation of MEK1 and MEK2 levels in cells and that, despite the dynamic changes in MEK1 and MEK2 levels, cells may maintain the net MEK protein levels and ERK1/2 activity relatively stable.

Figure 4. Prolonged high magnitude Raf/MEK/ERK activation is required to alter MEK1/2 levels.

(A) LNCaP-Raf:ER cells were treated with increasing doses of 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 2 days. The bottom panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 and MEK2 signals. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. Pearson’s r = 0.823 for MEK1 and −0.673 for MEK2. (B) LNCaP-Raf:ER cells were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for indicated time periods. Total cell lysates harvested at different time courses were analyzed for expression of indicated proteins by Western blotting. The bottom panel indicates densitometry of MEK1 and MEK2 signals. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments. Pearson’s r = 0.905 for MEK1 and −0.988 for MEK2.

3.5. The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway regulates MEK1 at a transcription level and MEK2 at a post-translational level

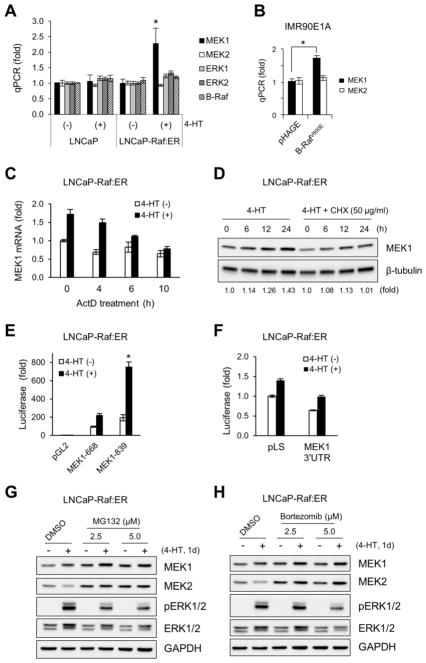

To understand by what mechanism(s) the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway regulates MEK1/2 levels, we measured their mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in LNCaP cells that stably express ΔRaf-1:ER. We found that Raf activation could significantly increase mRNA levels of MEK1 (Fig. 5A). However, Raf activation did not affect mRNA levels of MEK2, ERK1/2, or B-Raf in these cells, suggesting that only MEK1 mRNA levels are sensitive to Raf/MEK/ERK activity. Consistent with this data, ectopic expression of B-RafV600E also upregulated mRNA levels of MEK1, but not MEK2, in IMR90E1A cells (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway regulates MEK1 at a transcription level and MEK2 at a post-translational level.

(A) LNCaP-Raf:ER and the parental LNCaP cells were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 2 days. Expression of mRNA of indicated targets was examined by quantitative PCR. Data (mean ± standard error) are from a representative experiment conducted in triplicates and are expressed as fold changes relative to the untreated parental cells. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of MEK1 and MEK2 mRNA levels in IMR90E1A cells infected with pHAGE-B-RafV600E virus for 2 days. Data (mean ± standard error) are from a representative experiment conducted in triplicates and are expressed as fold changes relative to the untreated cells.*P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of MEK1 mRNA levels in LNCaP-Raf:ER cells treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 24 hours. Actinomycin D was added at the indicated time prior to termination of the 4-HT treatment. Data (mean ± standard error) are from a representative experiment conducted in triplicates and are expressed as fold changes relative to the untreated cells. Pearson’s r = −0.98 for 4-HT (+) effects. (D) Western blot analysis of total lysates of LNCaP-Raf:ER cells treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for indicated time periods in the presence/absence of 50 μg/ml cycloheximide. (E) LNCaP-Raf:ER cells transfected with the MEK1 promoter-luciferase reporters harboring 668 (−713 to −45) and 839 (−713 to +126) base pairs of human MEK1 promoter DNA were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 2 days. Data (mean ± standard error) are from a representative experiment conducted in triplicates and are expressed as fold changes relative to the untreated cells harboring the control plasmid, pGL2basic. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). (F) LNCaP-Raf:ER cells transfected with the MEK1 3′UTR luciferase reporter were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 2 days. Data (mean ± standard error) are from a representative experiment conducted in triplicates and are expressed as fold changes relative to the untreated cells harboring the control plasmid, pLightSwitch (pLS). (G and H) Western blot analysis of total lysates of LNCaP-Raf:ER cells treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 1 day in the presence of different doses of MG132 (G) and bortezomib (H). Equivalent volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as the vehicle control.

We also found that actinomycin D, an inhibitor of mRNA synthesis, could effectively inhibit Raf-induced upregulation of MEK1 mRNA levels in a manner commensurate to the duration of drug treatment (Fig. 5C). In a similar manner, cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, could also inhibit Raf-induced upregulation of MEK1 protein levels. These data suggested that Raf/MEK/ERK-induced MEK1 upregulation is attributed to increased expression of mRNA as well as protein. To further test this hypothesis, we generated the MEK1 promoter-luciferase reporters harboring 839 (−713 to +126) and 668 (−713 to −45) base pairs of human MEK1 promoter DNA. Raf activation significantly upregulated the activity of these reporters in LNCaP cells witin two days (about 2 and 3.5 fold respectively; Fig. 5E). It was previously reported that MEK1 expression can be regulated by the 3′ UTR of MEK1 mRNA [23]. Nevertheless, we did not detect any significant effect of Raf activation on a luciferase reporter containing the full length 3′UTR of MEK1 mRNA (Fig. 5F). These data suggest that Raf/MEK/ERK activation can upregulate cellular MEK1 levels by increasing its expression mainly at transcription level.

Although MEK2 mRNA levels were not affected by Raf activation (Fig. 5A and 5B), we found that the proteasome inhibitors MG132 and bortezomib could consistently block Raf-induced MEK2 downregulation without significantly affecting the pathway activity, as determined by ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5G and 5H). These data suggest an involvement of the proteasome activity in the Raf/MEK/ERK-mediated MEK2 downregulation. We also found that MG132 and bortezomib could augment Raf-induced MEK1 upregulation (Fig. 5G and 5H), which is in agreement with the hypothesis that Raf activation increases MEK1 expression.

3.6. MEK1 is required for Raf-induced prolonged ERK1/2 activation and expression of p21CIP mRNA

We previously demonstrated that transcriptional induction of p21CIP1 is a key mechanism for Raf/MEK/ERK to mediate growth inhibitory signaling [14, 15, 24, 25]. Because MEK1, but not MEK2, was upregulated in correlation with p21CIP1 induction upon Raf activation (Fig. 4), we determined whether MEK1 has a role for the p21CIP1 induction using RNA interference. Indeed, knockdown of MEK1 significantly decreased p21CIP1 mRNA levels within 2 days after Raf activation in LNCaP cells (Fig. 6A), indicating that MEK1 upregulation has functional significance for the Raf-induced p21CIP1 induction. Nevertheless, although ineffective by itself, MEK2 knockdown augmented the blocking effects of MEK1 knockdown on p21CIP1 induction (Fig. 6A), indicating that there may be a threshold for MEK/ERK activity which determines cellular levels of p21CIP1 mRNA. In agreement with this idea, MEK1 knockdown significantly decreased the Western blot signals detected by the antibody specific to both MEK1 and MEK2 whereas MEK2 knockdown did not (Fig. 6B). Consistent with this, MEK1 knockdown also substantially decreased the Western blot signals for phosphorylated MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 whereas MEK2 knockdown did not (Fig. 6B). However, despite its clear effects on p21CIP1 mRNA levels, MEK1 knockdown did not effectively inhibit Raf-induced changes in protein levels of p21CIP1 and cyclin D1 although simultaneous knockdown of MEK1 and MEK2 effectively inhibited these changes (Fig. 6B), which suggests that there may be additional mechanisms affecting cellular protein levels of p21CIP1 under these conditions. These data suggest that MEK1 is likely to be the major MEK that mediates prolonged ERK1/2 signaling and is required for expression of p21CIP1 mRNA.

Figure 6. MEK1 upregulation is necessary for Raf-induced p21CIP1 expression.

LNCaP-Raf:ER, infected with pLL3.7 viruses expressing shRNA that targets mRNA of MEK1 (shMEK1) or MEK2 (shMEK2), were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen for 2 days. (A) Expression of mRNA of p21CIP1 was examined by quantitative PCR. Data (mean ± standard error) are from two independent experiments conducted in triplicates and are expressed as fold changes relative to pLL3.7, 4-HT (−). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; n.s., not significant (Student’s t test). (B) Total cell lysates were analyzed for expression of the indicated proteins by Western blotting.

4. Discussion

MEK1/2 are abundant in cells, present around 1 μM depending upon cell types, similarly to the levels of ERK1/2 [26]. In contrast, Raf is not as abundant as MEK1/2 or ERK1/2. Therefore, the greater molar ratio between Raf-MEK than between MEK-ERK makes MEK1/2 activation an important step for signal amplification in Raf/MEK/ERK signaling [26], which rationalizes MEK1/2 levels as a potential regulatory target for modulating the pathway activity. The data presented in this study demonstrate that the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway can regulate cellular levels of MEK1 and MEK2 via a feedback mechanism mediated by ERK1/2. Upon activation of the feedback mechanism, MEK1 levels were upregulated whereas MEK2 levels were downregulated. Our results suggest that the MEK1 upregulation is mediated at a transcriptional level whereas MEK2 downregulation is mediated at a posttranslational level sensitive to the proteasome activity. To our best knowledge, our study is the first demonstration of feedback regulation of cellular MEK1 and MEK2 levels.

Recent studies have demonstrated that cellular levels of the molecular switches in the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway can be regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms [reviewed in [27]]. For example, it has been reported that Hu antigen R (HuR) can regulate stability of MEK mRNA via the 3′ UTR [23] whereas human Pumilio2/PUM2 can regulate translation of ERK2 [28]. At the level of Ras, the miRNA Let-7 could regulate its protein levels [29]. However, it has not been reported whether any of the pathway components can be subject to a transcriptional regulation. Our demonstration of MEK1 transcriptional regulation expands the repertoire of the molecular mechanisms that regulate the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway. Intriguingly, our data show that MEK1 is selectively upregulated over MEK2. What is then the biological significance of the feedback expression of MEK1 as opposed to MEK2? It is noteworthy that MEK1 is subject to direct feedback phosphorylation and inhibition by ERK1/2 whereas MEK2 is not [9, 10]. By increasing MEK1 to ensure prolonged ERK1/2 signalling, cells may also increase a regulatable MEK.

Increasing evidences suggest that MEK1 and MEK2 may have distinct functions in determining the physiological output of pathway signaling. For example, gene deletion in mice revealed a critical difference in their requirement at an early developmental stage [30–32]. Their selective requirement in epidermal neoplasia was also reported [33]. In agreement with these findings, our present study demonstrates that knockdown of MEK1, but not MEK2, can block Raf-mediated p21CIP1 mRNA expression. This observation leads to a question on the mechanism underlying this selectivity. MEK1 and MEK2 are >86% identical at the amino acid level and evaluation of their constitutively active mutants has revealed functional redundancy in a large extent of cell physiology [15, 34–36], although MEK1 and MEK2 can exhibit distinct physical interactions with certain proteins, e.g., A-Raf [37] and the scaffold MP1 [38]. In the context of p21CIP1 regulation, we and others previously showed that overexpression of constitutively active MEK1 or MEK2 mutants was equally effective for inducing p21CIP1 expression in LNCaP and other cell lines [15, 36]. Therefore, it is hardly conceivable that the differential effects of MEK1 and MEK2 knockdown on p21CIP1 mRNA levels represent distinct intrinsic properties of MEK1 and MEK2. The distinct effects of MEK1 and MEK2 depletion on p21CIP1 mRNA expression appear to be attributed to their differential expression.

Our data suggest that the feedback mechanism(s) is turned by prolonged high magnitude Raf/MEK/ERK activity and that the mechanism is constitutively active in certain B-RafV600E tumor cells. Therefore, this feedback mechanism may have a tumor biological relevance. Indeed, we previously reported that upregulation of mortalin, as detected in melanoma patient tumor tissues, is important for B-RafV600E tumor cells to bypass p21CIP1 expression, which is activated as a tumor suppressive mechanism in response to aberrant MEK/ERK activation [14]. Intriguingly, upregulation of MEK/ERK activity was necessary for mortalin depletion to induce p21CIP1. The MEK1 feedback regulation observed in the present study may address a mechanism by which mortalin depletion upregulates MEK/ERK activity in B-RafV600E tumor cells, suggesting that mortalin upregulation in cancer may antagonize the feedback mechanism to suppress p21CIP1 expression and to avoid growth arrest. The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway can mediate not only cell proliferative but also growth inhibitory signaling, including cell death and cell cycle arrest in response to a variety of signals [reviewed in [39–42]]. This anti-proliferative pathway signaling has significance in different physiological settings, including early development, neuronal differentiation, and tumor suppression. Our findings raise an interesting question on the role of the differential feedback regulation of MEK1 and MEK2 in these physiological processes.

Highlights.

Cellular MEK1 and MEK2 levels are feed-back regulated upon prolonged high magnitude Raf/MEK/ERK activation.

MEK1 levels are upregulated at transcription level.

MEK2 levels are downregulated at post-translational levels.

MEK1 upregulation, but not MEK2 downregulation, is necessary for Raf-induced expression of p21CIP1 mRNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Hudson (Medical College of Wisconsin) and Richard Mulligan (Harvard Univ.) for pHAGE, and Jin-Hwan Kim for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA138441) and American Cancer Society (RSGM-10-189-01-TBE) to J.P.

Abbreviations

- 4-HT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrence MC, Jivan A, Shao C, Duan L, Goad D, Zaganjor E, Osborne J, McGlynn K, Stippec S, Earnest S, Chen W, Cobb MH. The roles of MAPKs in disease. Cell Res. 2008;18:436–442. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Montalto G, Cervello M, Nicoletti F, Fagone P, Malaponte G, Mazzarino MC, Candido S, Libra M, Basecke J, Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Milella M, Tafuri A, Cocco L, Evangelisti C, Chiarini F, Martelli AM. Mutations and deregulation of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR cascades which alter therapy response. Oncotarget. 2012;3:954–987. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–3290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291–3310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roskoski R., Jr ERK1/2 MAP kinases: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:105–143. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wortzel I, Seger R. The ERK Cascade: Distinct Functions within Various Subcellular Organelles. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:195–209. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaul YD, Seger R. The MEK/ERK cascade: from signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunet A, Pages G, Pouyssegur J. Growth factor-stimulated MAP kinase induces rapid retrophosphorylation and inhibition of MAP kinase kinase (MEK1) FEBS Lett. 1994;346:299–303. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eblen ST, Slack-Davis JK, Tarcsafalvi A, Parsons JT, Weber MJ, Catling AD. Mitogen-activated protein kinase feedback phosphorylation regulates MEK1 complex formation and activation during cellular adhesion. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2308–2317. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2308-2317.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty MK, Muller J, Ritt DA, Zhou M, Zhou XZ, Copeland TD, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Lu KP, Morrison DK. Regulation of Raf-1 by direct feedback phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rushworth LK, Hindley AD, O’Neill E, Kolch W. Regulation and role of Raf-1/B-Raf heterodimerization. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2262–2272. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2262-2272.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbalan-Garcia S, Yang SS, Degenhardt KR, Bar-Sagi D. Identification of the mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation sites on human Sos1 that regulate interaction with Grb2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5674–5682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu PK, Hong SK, Veeranki S, Karkhanis M, Starenki D, Plaza JA, Park JI. A Mortalin/HSPA9-Mediated Switch in Tumor-Suppressive Signaling of Raf/MEK/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:4051–4067. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00021-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong SK, Yoon S, Moelling C, Arthan D, Park JI. Noncatalytic function of ERK1/2 can promote Raf/MEK/ERK-mediated growth arrest signaling. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33006–33018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starenki D, Hong SK, Lloyd RV, Park JI. Mortalin (GRP75/HSPA9) upregulation promotes survival and proliferation of medullary thyroid carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong SK, Jeong JH, Chan AM, Park JI. AKT upregulates B-Raf Ser445 phosphorylation and ERK1/2 activation in prostate cancer cells in response to androgen depletion. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1732–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong SK, Kim JH, Lin MF, Park JI. The Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway can mediate growth inhibitory and differentiation signaling via androgen receptor downregulation in prostate cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:2671–2682. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazar DF, Wiese RJ, Brady MJ, Mastick CC, Waters SB, Yamauchi K, Pessin JE, Cuatrecasas P, Saltiel AR. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition does not block the stimulation of glucose utilization by insulin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20801–20807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan FM, Shao Y, Mayberry MM, Aplin AE. Hyperactivation of MEK-ERK1/2 signaling and resistance to apoptosis induced by the oncogenic B-RAF inhibitor, PLX4720, in mutant N-RAS melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:366–371. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuels ML, Weber MJ, Bishop JM, McMahon M. Conditional transformation of cells and rapid activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by an estradiol-dependent human raf-1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6241–6252. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang PY, Rao JN, Zou T, Liu L, Xiao L, Yu TX, Turner DJ, Gorospe M, Wang JY. Post-transcriptional regulation of MEK-1 by polyamines through the RNA-binding protein HuR modulating intestinal epithelial apoptosis. The Biochemical journal. 2010;426:293–306. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu PK, Hong SK, Yoon SH, Park JI. Active ERK2 is sufficient to mediate growth arrest and differentiation signaling. FEBS J. 2015;282:1017–1030. doi: 10.1111/febs.13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karkhanis M, Park JI. Sp1 regulates Raf/MEK/ERK-induced p21 transcription in TP53-mutated cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2015;27:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrell JE., Jr Tripping the switch fantastic: how a protein kinase cascade can convert graded inputs into switch-like outputs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:460–466. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whelan JT, Hollis SE, Cha DS, Asch AS, Lee MH. Post-transcriptional regulation of the Ras-ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1235–1241. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MH, Hook B, Pan G, Kershner AM, Merritt C, Seydoux G, Thomson JA, Wickens M, Kimble J. Conserved regulation of MAP kinase expression by PUF RNA-binding proteins. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giroux S, Tremblay M, Bernard D, Cardin-Girard JF, Aubry S, Larouche L, Rousseau S, Huot J, Landry J, Jeannotte L, Charron J. Embryonic death of Mek1-deficient mice reveals a role for this kinase in angiogenesis in the labyrinthine region of the placenta. Curr Biol. 1999;9:369–372. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belanger LF, Roy S, Tremblay M, Brott B, Steff AM, Mourad W, Hugo P, Erikson R, Charron J. Mek2 is dispensable for mouse growth and development. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4778–4787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4778-4787.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nadeau V, Guillemette S, Belanger LF, Jacob O, Roy S, Charron J. Map2k1 and Map2k2 genes contribute to the normal development of syncytiotrophoblasts during placentation. Development. 2009;136:1363–1374. doi: 10.1242/dev.031872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholl FA, Dumesic PA, Barragan DI, Harada K, Charron J, Khavari PA. Selective role for Mek1 but not Mek2 in the induction of epidermal neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3772–3778. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansour SJ, Candia JM, Gloor KK, Ahn NG. Constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAPKK1) and MAPKK2 mediate similar transcriptional and morphological responses. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voisin L, Julien C, Duhamel S, Gopalbhai K, Claveau I, Saba-El-Leil MK, Rodrigue-Gervais IG, Gaboury L, Lamarre D, Basik M, Meloche S. Activation of MEK1 or MEK2 isoform is sufficient to fully transform intestinal epithelial cells and induce the formation of metastatic tumors. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guegan JP, Ezan F, Gailhouste L, Langouet S, Baffet G. MEK1/2 overactivation can promote growth arrest by mediating ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of p70S6K. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:903–915. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu X, Noh SJ, Zhou G, Dixon JE, Guan KL. Selective activation of MEK1 but not MEK2 by A-Raf from epidermal growth factor-stimulated Hela cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3265–3271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaeffer HJ, Catling AD, Eblen ST, Collier LS, Krauss A, Weber MJ. MP1: a MEK binding partner that enhances enzymatic activation of the MAP kinase cascade. Science. 1998;281:1668–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park JI. Growth arrest signaling of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cancer. Front Biol (Beijing) 2014;9:95–103. doi: 10.1007/s11515-014-1299-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramaniam S, Unsicker K. ERK and cell death: ERK1/2 in neuronal death. FEBS J. 2010;277:22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mebratu Y, Tesfaigzi Y. How ERK1/2 activation controls cell proliferation and cell death: Is subcellular localization the answer? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1168–1175. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cagnol S, Chambard JC. ERK and cell death: mechanisms of ERK-induced cell death--apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. FEBS J. 2010;277:2–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]