Abstract

Generic drugs are interchangeable with original proprietary drugs, as they have the same active pharmaceutical ingredients, dosage forms, strength, quality, indications, effects, directions, and dosage. The cost of generic drugs is lower than original drugs, because the developmental cost is lower. The expansion of medical expenses is an important issue in many countries, including Japan, the USA, and Europe, and promotion of generic drugs has been demanded to solve this issue in Japan. Generic drug approval review in Japan is conducted by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), which reviews the equivalence of the original drugs from the viewpoint of quality, efficacy, and safety, based on documentation submitted by the generic drug applicants. However, the details of the generic drug review in Japan have not been reported. In this report, we introduce the application types, the number of applications and approvals, and the review timeline of generic drugs in Japan. In addition, we discuss recent consultations and future prospects.

KEY WORDS: approval review, generic drug, Japan, PMDA

INTRODUCTION

A generic drug is defined as a drug with the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), dosage form, strength, quality, indication, effect, direction, and dose as the original proprietary drug. In Japan, the drug product containing an API that has the different hydrate form or crystalline form from the original drug can essentially apply for as a generic drug, because they have basically the same chemical structure. The drug product containing an API that has different salts, esters, and ethers from the original drug can apply for as a new drug, not a generic drug. The original drugs are given the reexamination period of 8 years at the time of approval. The applicant can apply for the generic drugs after the reexamination period of original drugs. Because generic drugs are approved after the patent expiration of the original drugs and a reexamination period in Japan, the generic drugs have a reduced development cost, as compared to the original drugs. Therefore, the generic drug price is cheaper than the original drug. For example, in Japan, the price of a generic drug is usually 60% of the original drug price. Recently, demand has increased for reduced medical expenses in many countries including Japan, the USA, and Europe (1, 2). Over 20% of Japan’s population is over the age of 65 years, and it is estimated that it will reach nearly 40% by 2050 (3). This is a key factor for healthcare cost expansion in Japan. The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) proposed the use of generic drugs to reduce healthcare costs in 2007. In particular, the generic drug market share in Japan was lower than in other developed countries, as the market share of generic drugs in Japan was 18.7% in 2007 (4). In contrast, the market share of generic drugs was 72% in the USA, 65% in England, and 63% in Germany. One of the reasons for the low generic drug market share in Japan is that there was no substitution right for the pharmacists. The physicians had the decision right of the generic drug substitution before 2006. In 2006, one important change of public health insurance was that the pharmacists were given right to substitute generic drugs for original drugs if the physicians explicitly allow substitution on their prescription format. The prescription format before 2008 was the format that the pharmacists could not change to generic drugs unless the physicians signed in the “substitution” space on the prescription. The change of the prescription format was carried out in 2008, and it was changed to “No substitutions“ from “substitutions.” If there is no checkmark in the “No substitutions” space on the prescription, the pharmacists were given right to substitute to generic drugs. In this prescription format, a space was provided for “a signature in case all prescription drugs cannot be changed to generic drugs.” With the signature of physicians, all prescription drugs could not be substituted. In 2012, the prescription format was modified to one that allowed generic substitution for individual drug, making it easier to substitute to generic drugs. Many actions including the prescription format change are carried out in Japan to promote the generic drugs usage (4). Additionally, in 2013, the MHLW announced a 5-year plan to expand the use of generic drugs to over 60% by 2018 (4, 5). In order to promote the use of generic drugs, accelerated approval review for generic drugs is indispensable.

The Office of Generic Drugs, part of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), is responsible for the approval review of generic drugs in Japan. The PMDA reviews the equivalence of generic and original drugs from the viewpoint of quality, efficacy, and safety, based on a document submitted by generic drug applicants. Table I shows the necessary data at the time of application for the original drug and new generic drug. At the time of original (new) drug application, documents regarding the quality, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and clinical studies are required. In contrast, at the time of generic drug application, only documents regarding specifications, test methods, accelerated testing, and bioequivalence (BE) studies are required. In addition, the submission of long-term storage test data may be required if the drug stability cannot be assumed based on the original drug (e.g., polymorphic form differences, hydrate differences). BE studies are the commonly accepted method to demonstrate therapeutic equivalence between the original and generic drug. In BE studies, bioavailability (BA) is compared between the original and generic drug. BA is defined as the rate and extent of active ingredient or metabolite absorption from a drug product. Peak plasma concentration (Cmax) is used as the rate of absorption, and area under the drug-plasma concentration versus time profile (area under curve [AUC]) is used as the extent of absorption. Japan adopts it like the USA and Europe that the 90% confidence interval of difference in the average values of logarithmic parameters to be assessed between the original and generic drugs is within the acceptable range of log (0.80)–log (1.25) for the Cmax and AUC. As the different point for the acceptance criteria, even though the confidence interval is not in the range, the generic drugs are accepted as bioequivalent, if the following three conditions are satisfied. They are that the total sample size of the bioequivalence study is not less than 20, the dissolution rates of original and generic drugs are evaluated to be similar, and the differences in average values of logarithmic parameters to be assessed between two products are between log (0.90) and log (1.11). As shown in Table II, BE study guidelines were published on February 29, 2012, in Japan. However, the details of generic drug review in Japan have not been reported.

Table I.

Summary of the Data Requirements for New Generic Drug Applications in Japan

| Content of the data submitted for application | New drug | New generic drug | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Origin or background of discovery and conditions of use in foreign countries | 1. Origin or background of discovery | 〇 | × |

| 2. Conditions of use in foreign countries | 〇 | × | |

| 3. Special characteristics, comparisons with other drugs, and related information | 〇 | × | |

| B. Manufacturing methods, standards, and test methods | 1. Chemical structure, physicochemical properties, and related information | 〇 | × |

| 2. Manufacturing methods | 〇 | △ | |

| 3. Specifications and test methods | 〇 | 〇 | |

| C. Stability | 1. Long-term storage tests | 〇 | × |

| 2. Tests under severe conditions | 〇 | × | |

| 3. Accelerated tests | 〇 | 〇 | |

| D. Pharmacological action | 1. Primary pharmacology | 〇 | × |

| 2. Secondary pharmacology, safety pharmacology | 〇 | × | |

| 3. Other pharmacology | 〇 | × | |

| E. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion | 1. Absorption | 〇 | × |

| 2. Distribution | 〇 | × | |

| 3. Metabolism | 〇 | × | |

| 4. Excretion | 〇 | × | |

| 5. Bioequivalence | 〇 | 〇 | |

| 6. Other ADME | 〇 | × | |

| F. Acute, subacute, and chronic toxicity, teratogenicity, and other types of toxicity | 1. Single-dose toxicity | 〇 | × |

| 2. Repeated dose toxicity | 〇 | × | |

| 3. Genotoxicity | 〇 | × | |

| 4. Carcinogenicity | 〇 | × | |

| 5. Reproductive toxicity | 〇 | × | |

| 6. Local irritation | 〇 | × | |

| 7. Other toxicity | 〇 | × | |

| G. Clinical studies | 1. Clinical trial results | 〇 | × |

In principle, 〇 means that the indicated data is required. × means that the indicated data is not required. △ indicates necessity of the indicated data is case based

Table II.

Various Bioequivalence Guidelines in Japan

| Guideline for bioequivalence studies of generic products | http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide(e)/Generic/GL-E_120229_BE.pdf |

| Guideline for bioequivalence studies of generic products for different strengths of oral solid dosage forms | http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide(e)/strength/GL-E_120229_ganryo.pdf |

| Guideline for bioequivalence studies for formulation changes of oral solid dosage forms | http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide(e)/form/GL-E_120229_shohou.pdf |

| Guideline for bioequivalence studies for different oral solid dosage forms | http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide(e)/GL-E_120229_zaikei.pdf |

In this report, we introduce the application types, the number of applications and approvals, and the review timeline of generic drugs in Japan. In addition, we discuss recent consultations and future generic drug prospects.

Application Types, Number of Applications and Approvals, and a Review of the Generic Drug timeline

There are two application types for new generic drugs and partial change approval in Japan. New generic drug applications are submitted as the first application, and partial change applications are submitted after for post-approval changes. The approval content in Japan includes the indication, effects, directions, dose, specifications, test methods, storage method, validity period, manufacturing method, formulation or manufacturing site, and brand name. If the applicant for a generic drug performs post-approval change on these contents, with the exception of minor changes, the PMDA review is necessary for partial change approval.

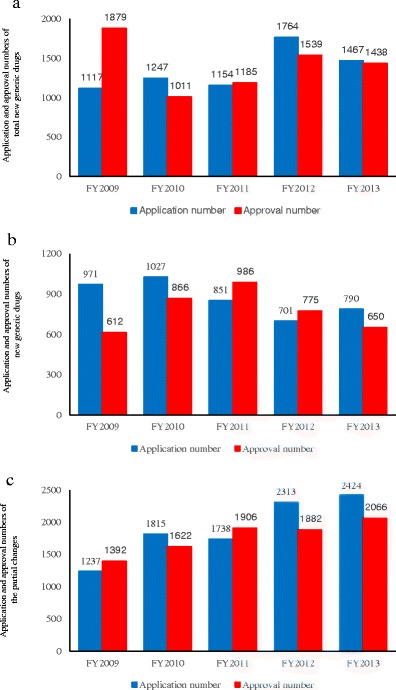

Figure 1 shows the number of generic drug applications and approvals in Japan. Application and approval numbers include brand name changes for existing, approved generic drugs, in addition to new generic drugs. The numbers vary greatly each fiscal year, with approximately 1000–1900 generic drugs submitted and approved annually (Fig. 1a). Figure 1b shows the number of new generic drug applications and approvals. The approval of new generic drugs reached a peak in fiscal year (FY) 2011 and has decreased thereafter. However, partial change applications and approvals have increased year to year, with 2424 partial change applications submitted and 2066 partial change applications approved in FY2013 (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Application and approval numbers for generic drugs in Japan. The blue graph shows the number of applications, while the red graph shows the number of approvals. Application and approval numbers of total new generic drugs a, new generic drugs b, and partial changes c for each fiscal year. In addition, numbers may change slightly based on search style

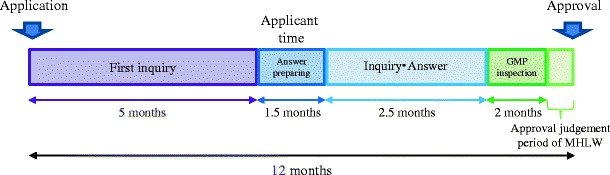

Next, we will introduce the review timeline for new generic drug approval in Japan. The total time from new generic drug application to approval is generally 12 months (Fig. 2). New generic drugs are approved in February and August, because the national health insurance drug price list is updated twice a year, in June and December. The application review time is 9 months, and MHLW approval procedures and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) inspections are conducted during the remaining 3 months. First, the generic drug applicant must apply for drug authorization. Next, the PMDA reviews the submission dossier and sends the first inquiry to the applicant within 5 months of application submission. The applicant must respond to the PMDA inquiry within 1.5 months. The PMDA and applicant may correspond three to four times during the inquiry. In contrast, the application review time for partial change approval varies based on the application content. Table III shows the general time required for each type of partial change approval and the target time from application to approval. When partial change approval is submitted for manufacturing methods, there are two timelines, 6 or 12 months. The protocol for manufacturing method approval was amended by the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in April 2005. Per this amendment, the review time for manufacturing method changes for generic drugs approved before April 2005 is 12 months, because the review is conducted similar to a first time application. In contrast, for generic drug application after April 2005, the target time is 6 months, because the manufacturing methods were reviewed at the time of new generic drug application. Changes to drug formulation have different target times than manufacturing method review, although the rationale is similar. For manufacturing site changes, approval can take 3, 6, or 12 months, depending on whether the manufacturing method is changed. Although when the manufacturing method has never been reviewed, the target approval time is 12 months. When a part of the previously reviewed manufacturing method is changed, the target time for approval is 6 months. However, if only the manufacturing site is changed, the target time is 3 months. The PMDA seeks to have a rapid total review time for partial change approval, improving the 50th percentile (median) every year. The current goal is 15 months for FY2014, 14 months for FY2015, 13 months for FY2016, 12 months for FY2017, and 10 months for FY2018 (6). With the number of applications for partial change approval increasing (2424 in FY2012), we set the target time as 15 months for FY2014. This is similar to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which seeks to review 60% of new generic drug submissions within 15 months of the submission date in FY2015, 75% within 15 months for FY2016, and 90% within 10 months for FY2017 (7, 8). Furthermore, the FDA aims to review 60% of major amendment within 10 months for FY2015, 75% within 10 months for FY2016, and 90% within 10 months for FY2017. Finally for minor amendments, the FDA aims to review 60% within 3 months for FY2015, 75% within 3 months for FY2016, and 90% within 3 months for FY2017. We cannot compare the review time directly, because the review time in Japan uses the median, and the content is different between Japan and the USA. Nevertheless, decreasing review time is a common goal for both agencies.

Fig. 2.

Review of the timeline for new generic drug approval

Table III.

Review Time of the Application for Partial Change Approval

| Indication and effects | 6 months | |

| Direction and dose | 6 months | |

| Specifications and test methods | 6 months | |

| Storage method and validity period | 6 months | |

| Manufacturing method | When the manufacturing method has been already reviewed | 6 months |

| When the manufacturing method has never been reviewed | 12 months | |

| Formulation | When the manufacturing method has been already reviewed | 6 months |

| When the manufacturing method has never been reviewed | 12 months | |

| Manufacturing site | When all of the reviewed manufacturing method is the same | 3 months |

| When a part of the reviewed manufacturing method is changed | 6 months | |

| When manufacturing method has never been reviewed | 12 months |

Consultation Meetings

In January 2012, we started conducting consultation meetings to facilitate and accelerate the development of generic drugs. Presently, we are holding consultations regarding BE studies and quality requirements for generic drugs. Table IV shows the implementation number for each fiscal year, which has increased annually. The PMDA and generic drug applicants discuss generic drug quality, such as the sufficiency of the stability test or the validity of test in generic quality consultation. In generic BE consultations, we discuss BE evaluation methods, such as endpoint validity, number of subjects, and analytes to be measured. Recently, there has been much discussion of difficult drug products, such as dry powder inhaler drug products and liposome drug products. We hope that these consultations will lead to effective generic drug development.

Table IV.

Implementation Number for Consultation Meetings Each Fiscal Year

| FY2011 | FY2012 | FY2013 | FY2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation on bioequivalence studies for generic drugs | 1 | 8 | 15 | 17 |

| Consultation on quality requirements for generic drugs | 2 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Total | 3 | 10 | 18 | 26 |

Future Prospects

The Office of Generic Drugs of the PMDA is considering each of the following topic:

Recommend an application in the common technical document (CTD) format (in the future, e-CTD format)

Ensure transparency of reviews by preparing and disclosing review reports on new generic drugs

Consider whether to accept biopharmaceutics classification system (BCS)-based biowaivers

Research BE guidelines for dry powdered inhaler drug products

The CTD format is a set of guidelines developed in 2004 at the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) for the purpose of unifying standards for new drug approval globally (9). The CTD format is already the standard format for new drug applications. However, there is no standard format for generic drug applications in Japan. In addition, a new drug review report is being written and disclosed in Japan, although one has not been developed for generic drugs. These two topics are being announced in the third PMDA 5-year mid-term plan (FY2014–2018) (6).

BCS classifies the four drug classes by solubility and permeability, as proposed by Amidon et al. in 1995 (10). This method is used to avoid BE studies during generic drug development and is referred to as the BCS-based biowaiver. This concept has already been accepted in the USA and Europe (11). The PMDA and MHLW are considering whether BCS-based biowaivers should be accepted in Japan.

Recent consultations have evaluated generic drug development for dry powdered inhaler drug products. In Europe and the USA, guidelines for dry powder inhalers have already been published (12, 13). Therefore, the Office of Generic Drugs of the PMDA is going to initiate studies to develop dry powder inhaled drug guidelines in the future.

CONCLUSION

In this report, we introduced the application types, the number of applications and approvals, and the review timeline of generic drugs in Japan. Additionally, we introduced our consultation meetings and future prospects. In Japan, generic drug usage is promoted to reduce medical expenses among the aging population. We believe that accelerating and ensuring transparency of generic drug review is important. This is the first report to discuss the details of generic drug regulation in Japan. We hope this report clarifies generic drug regulation of Japan.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the Offices of Generic Drugs of PMDA for their helpful advice.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency.

References

- 1.IMS HEALTH. Generic medicines: essential contributors to the long-term health of society. 2009. http://www.imshealth.com/imshealth/Global/Content/Document/Market_Measurement_TL/Generic_Medicines_GA.pdf#search=’the+reduction+of+medical+expense+%2C+generic%2CUS+and+Europe. Accessed 24 Feb 2015.

- 2.IMS Institute For Healthcare Iinformatics. Avoidable costs in U.S. healthcare. 2013. http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Institute/RUOM-2013/IHII_Responsible_Use_Medicines_2013.pdf#search=’the+reduction+of+medical+expense+%2C+generic%2CUS. Accessed 24 Feb 2015

- 3.Ortman, J. M., Velkoff, V. A. Howard Hogan. United States Census Bureau. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. 2014. http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/ p25-1140.pdf#search=’40+%25%2C+Japan%2C+2050%2C65. Accessed 24 Feb 2015.

- 4.MHLW. Promotion of the use of generic drugs. 2012. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy_report/ 2012/09/120921.html. Accessed 24 Feb 2015.

- 5.Simon-Kucher & Partners Healthcare Insights. Recent developments in global pricing & market access. 2013. Healthcare Insights. http://www.simon-kucher.com/sites/default/files/hci_summer2013_volumevi_ issue2.pdf#search=’2013%2C+MHLW+%2C+generic%2C+60%25+%2C+2018. Accessed 24 Feb 2015.

- 6.PMDA, MHLW. Mid-term plan of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). 2014. http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000198796.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2015.

- 7.FDA. Generic drug user fee act program performance goals and procedures. 2013. http://www.fda. gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/GenericDrugUserFees/UCM282505.pdf. Accessed 24 Feb 2015:P1-9.

- 8.FDA. Guidance for industry, ANDA submissions—amendments and easily correctable deficiencies under GDUFA. 2014. . http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ Guidances/UCM404440.pdf#search=’First+major+amendment%2C+FDA. Accessed 24 Feb 2015.

- 9.ICH harmonised tripartite guideline. Organization of the common technical document for the registration of pharmaceuticals for human use M4. 2004. http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000156342.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2015.

- 10.Amidon GL, Lennernas H, Shah VP, Crison JR. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharmaceutical research. 1995;12(3):413–20. doi: 10.1023/A:1016212804288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davit B, Braddy AC, Conner DP, Yu LX. International guidelines for bioequivalence of systemically available orally administered generic drug products: a survey of similarities and differences. The AAPS journal. 2013;15(4):974–90. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9499-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guidelines on the requirements for clinical documentation for orally inhaled products (OIP) including the requirements for demonstration of therapeutic equivalence between two inhaled products for use in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults and for us in the treatment of asthma in children and adolescents. 2009. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library /Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003504.pdf Accessed 25 Feb 2015.

- 13.FDA. Draft guidance on fluticasone propionate; salmeterol xinafoate. 2013. http://www.fda.gov/ downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM367643.pdf Accessed 25 Feb 2015.