Abstract

We report the first case of Corynebacterium propinquum keratitis in the compromised cornea of a diabetic patient wearing therapeutic contact lenses. The strain was identified to the species level based on sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and RNA polymerase β-subunit-encoding gene (rpoB). Ophthalmologists should be aware of nondiphtherial corynebacterial infection of compromised corneas.

CASE REPORT

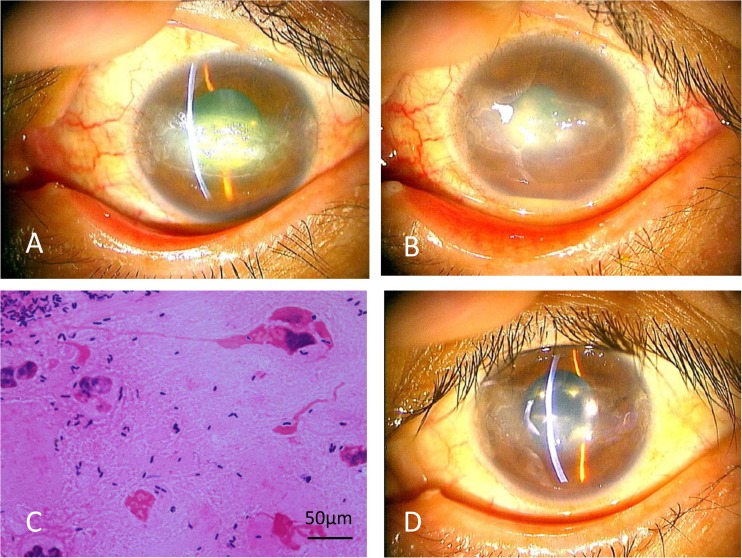

This case consisted of a 44-year-old woman with a history of type 1 diabetes, hemodialysis due to diabetic nephropathy, vitrectomy in both eyes due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and cataract surgery in both eyes. She complained of decreased vision of the left eye without any irritation and was referred to our department because of a persistent corneal epithelial defect. The corrected vision was 0.02 in the right eye, with hand motion detectable by the left eye. Intraocular pressure was 14 mm Hg in both eyes. She had disturbance on blinking and exhibited epithelial damage in the area of the palpebral fissure in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination showed epithelial defect, pannus formation, and white plaque without obvious injection in the left cornea (Fig. 1A). To treat her left cornea, the white plaque was removed and punctal plugs were inserted; the patient was provided with therapeutic bandage contact lenses, and 0.1% hyaluronic acid was administered six times per day in both eyes. After 3 weeks, the corneal epithelial defect of the left eye improved, and the left vision recovered to 0.03. However, after an additional 3 days, hypopyon and corneal infiltration had developed in the left eye (Fig. 1B). We suspected infectious keratitis and removed the contact lens. A corneal scraping was obtained, subjected to Gram staining, and observed by light microscopy. The smear revealed numerous coryneform Gram-positive rods with phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) (Fig. 1C). We suspected nondiphtherial Corynebacterium keratitis and switched the eye drops to gatifloxacin (GAT) and cefmenoxime administered (separately) six times per day each. Complete eye closure with eye patch was added because of poor reepithelialization, and systemic intravenous ampicillin also was added. The epithelial defect gradually healed, but complete epithelialization took about 2 months (Fig. 1D). The final visual acuity recovered to 0.02. Bacterial culture yielded Corynebacterium species.

FIG 1.

(A) Photograph of slit-lamp examination of the left cornea at the first visit. Observation revealed the presence of an epithelial defect accompanied by white plaque and pannus formation. (B) The cornea was treated by corneal scraping, punctal plugs, therapeutic contact lens, and topical 0.1% hyaluronic acid. However, after a further 3 days, hypopyon and corneal infiltration had developed. (C) Photograph of a Gram-stained specimen from the corneal scraping. Gram-positive rods with phagocytosis by PMNs are observed. (D) The cornea at 2 months after the first visit, following antibiotic treatment against Corynebacterium propinquum. The epithelial defect has healed.

Bacterial species identification.

The genus of the bacterial isolate, designated MGJ001, was shown to be Corynebacterium by microscopic observation and biochemical tests. Identification of the isolate to the species level, performed by biochemical testing using API Coryne (1) (bioMérieux SA, Lyon, France), indicated that the strain was Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum. The DNA sequence of the 16S rRNA gene, which was amplified by PCR with the primer pair 10F (5′-GTTTGATCCTGGCTCA-3′) and 800R (5′-TACCAGGGTATCTAATCC-3′), showed 99% homology with both C. pseudodiphtheriticum and C. propinquum by the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). To confirm the species identification, partial DNA sequence of the RNA polymerase β-subunit-encoding gene (rpoB), amplified by PCR with primer pair C2700F (CGAATGAACATCGGTCAGGT) and C3130R (TCCATCTCACCGAAACGCTG), also was determined (2). The obtained DNA sequence showed 100% homology with C. propinquum and 94% homology with C. pseudodiphtheriticum. Taken together, these data permit identification of the isolate as C. propinquum.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

The antibiotic susceptibilities of the isolate were determined by Etest (bioMérieux SA) on Mueller-Hinton agar according to the suppliers' instructions. The results are shown in Table 1. The strain showed macrolide and lincosamide resistance.

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of Corynebacterium propinquum strain determined by Etest

| Antibiotica | MGJ001 |

|

|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/ml) | Interpretationb | |

| CRO | 0.125 | S |

| CAZ | 0.5 | S |

| IPM | 0.016 | S |

| MEM | 0.08 | S |

| ERY | >256 | R |

| AZM | >256 | R |

| CLR | 32 | R |

| TOB | 0.5 | S |

| DOX | 2 | S |

| CIP | 2 | I |

| LVX | 1 | S |

| MFX | 0.5 | S |

| VAN | 1 | S |

| TEC | 0.25 | S |

| DAP | <0.016 | S |

| Tigecycline | 0.5 | S |

Abbreviations: CRO, ceftriaxone; CAZ, ceftazidime; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; ERY, erythromycin; AZM, azithromycin; CLR, clarithromycin; TOB, tobramycin; DOX, doxycycline; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin; VAN, vancomycin; TEC, teicoplanin; and DAP, daptomycin.

Interpretation of susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R) was based on the supplier's instructions.

Nondiphtherial corynebacteria, which are rod-shaped Gram-positive bacteria, are a component of the bacterial microflora of human skin and mucosa, including ocular surfaces (3, 4). These bacteria occasionally cause conjunctivitis in aged patients, suture-related corneal infection, and on rare occasions, keratitis in compromised ocular surfaces (5–11). However, there is little information about which species are related to keratitis, because species identification is not performed routinely in most hospitals or laboratories.

It is known that Corynebacterium macginleyi is the dominant species among nondiphtherial corynebacteria isolated from the normal conjunctival sac and from cases of bacterial conjunctivitis (3, 5, 8–11). However, the literature contains only a few reports of corneal infection caused by C. macginleyi (6, 11, 12). To date, Corynebacterium species other than C. macginleyi reported to cause keratitis have included the following: C. striatum (13, 14), C. xerosis (14), C. pseudodiphtheriticum (15), C. amycolatum (T. Toibana and H. Eguchi, unpublished data), and C. propinquum (this case). C. macginleyi is a lipophilic corynebacterium; the other species are nonlipophilic (16, 17). This distinction suggests that C. macginleyi, which requires lipids for growth, may prefer sebaceous glands to corneal surfaces. Factors contributing to colonization and virulence should be studied further.

In the present case, we first considered C. pseudodiphtheriticum infection because of the result of API Coryne, which differentiates between C. pseudodiphtheriticum and C. propinquum primarily on the basis of the detection of urease activity. However, a recent report reveals the existence of urease-producing strains of C. propinquum; this observation means that C. propinquum isolates may have been misidentified as C. pseudodiphtheriticum and that full differentiation will require sequencing of the rpoB locus (18). Indeed, in the case described in the present work, neither API Coryne nor the 16S rRNA gene sequence was sufficient to accurately identify the isolate to the species level; rpoB gene sequence was needed to demonstrate that the causative strain was C. propinquum.

C. propinquum is typically a harmless commensal of human nasopharynx and skin (18, 19). This species has been implicated in various opportunistic infections, such as respiratory infection (17, 20–24), bacteremia (17, 25, 26), endocarditis (27), osteitis (28), pleural effusion (29), rhino-sinusal infection (30), infection after osteosynthesis (31), trichomycosis axillaris (32), and nongonococcal urethritis (33). To date, infectious keratitis caused by C. propinquum has not been reported; to our knowledge, this study presents the first reported case of C. propinquum keratitis.

In this case, we empirically selected topical GAT and cefmenoxime; intravenous ampicillin subsequently was added in response to a previous report suggesting susceptibility of this species to penicillin (4, 18). The majority of C. propinquum strains are constitutively resistant to the macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B as a result of the presence of the erm(X) gene (19). The isolate MGJ001 also was resistant to macrolides and lincosamides, strongly suggesting the presence of erm(X). The strain MGJ001 exhibited susceptibility to novel antibiotics, including daptomycin and tigecycline, consistent with susceptibilities observed in a previous report (18).

Keratitis is a corneal infection that usually develops after ocular trauma, contact lens wear, or various predisposing corneal diseases. Keratitis can cause severe visual disturbance, mainly by corneal scarring. In our case, infection developed in compromised cornea following the wearing of therapeutic contact lenses for a persistent epithelial defect in a patient with severe diabetes. The corneal finding was characterized by white plaques on the epithelial defects. Keratitis with white plaque is a rare corneal condition that is usually caused by less-virulent atypical microorganisms (34). Nondiphtherial corynebacteria, including C. propinquum, also should be considered possible causative agents of corneal white plaque, and compromised corneal surfaces (including persistent epithelial defects) might be a risk factor. As we demonstrate here, direct microscopic examination of corneal scrapings is useful for the accurate diagnosis of opportunistic corneal infection.

In summary, we report the first case of C. propinquum keratitis accompanied by white plaque; in this case, infection developed in an eye with a compromised cornea in a diabetic patient wearing therapeutic contact lenses. The identities of the causative agents were proven by corneal smear, bacterial culture, and DNA sequences of the 16S rRNA and rpoB genes. Ophthalmologists should be aware of the potential for nondiphtherial corynebacterial infection of compromised corneas.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the rRNA gene and rpoB gene of MGJ001 are available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession no. LC033494 and LC063620, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soto A, Zapardiel J, Soriano F. 1994. Evaluation of API Coryne system for identifying coryneform bacteria. J Clin Pathol 47:756–759. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.8.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khamis A, Raoult D, La Scola B. 2004. rpoB gene sequencing for identification of Corynebacterium species. J Clin Microbiol 42:3925–3931. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.3925-3931.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riegel P, Ruimy R, de Briel D, Prevost G, Jehl F, Christen R, Monteil H. 1995. Genomic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among lipid-requiring diphtheroids from humans and characterization of Corynebacterium macginleyi sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 45:128–133. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-1-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eguchi H. 2013. Ocular infections caused by Corynebacterium species, p 75–82. In Basak S. (ed), Infection control. InTech, Rijeka, Croatia. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eguchi H, Kuwahara T, Miyamoto T, Nakayama-Imaohji H, Ichimura M, Hayashi T, Shiota H. 2008. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in ophthalmic clinical isolates belonging to the species Corynebacterium macginleyi. J Clin Microbiol 46:527–532. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01741-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki T, Iihara H, Uno T, Hara Y, Ohkusu K, Hata H, Shudo M, Ohashi Y. 2007. Suture-related keratitis caused by Corynebacterium macginleyi. J Clin Microbiol 45:3833–3836. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01212-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukumoto A, Sotozono C, Hieda O, Kinoshita S. 2011. Infectious keratitis caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant corynebacterium. Jpn J Ophthalmol 55:579–580. doi: 10.1007/s10384-011-0052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsuwaidi AR, Wiebe D, Burdz T, Ng B, Reimer A, Singh C, Bernard K. 2010. Corynebacterium macginleyi conjunctivitis in Canada. J Clin Microbiol 48:3788–3790. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01289-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giammanco GM, Di Marco V, Priolo I, Intrivici A, Grimont F, Grimont PA. 2002. Corynebacterium macginleyi isolation from conjunctival swab in Italy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 44:205–207. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(02)00438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joussen AM, Funke G, Joussen F, Herbertz G. 2000. Corynebacterium macginleyi: a conjunctiva specific pathogen. Br J Ophthalmol 84:1420–1422. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.12.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funke G, Pagano-Niederer M, Bernauer W. 1998. Corynebacterium macginleyi has to date been isolated exclusively from conjunctival swabs. J Clin Microbiol 36:3670–3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruoff KL, Toutain-Kidd CM, Srinivasan M, Lalitha P, Acharya NR, Zegans ME, Schwartzman JD. 2010. Corynebacterium macginleyi isolated from a corneal ulcer. Infect Dis Rep 2:1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidemann DG, Dunn SP, Diskin JA, Aiken TB. 1991. Corynebacterium striatus keratitis. Cornea 10:81–82. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199101000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubinfeld RS, Cohen EJ, Arentsen JJ, Laibson PR. 1989. Diphtheroids as ocular pathogens. Am J Ophthalmol 108:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li A, Lal S. 2000. Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum keratitis and conjunctivitis: a case report. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 28:60–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2000.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funke G, Bernard KA. 2011. Coryneform Gram-positive rods, p 413–442. In Versalovic J. (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 10th ed American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riegel P, Ruimy R, Christen R, Monteil H. 1996. Species identities and antimicrobial susceptibilities of corynebacteria isolated from various clinical sources. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 15:657–662. doi: 10.1007/BF01691153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard K, Pacheco AL, Cunningham I, Gill N, Burdz T, Wiebe D. 2013. Emendation of the description of the species Corynebacterium propinquum to include strains which produce urease. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 63:2146–2154. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.046979-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olender A. 2013. Antibiotic resistance and detection of the most common mechanism of resistance (MLSB) of opportunistic Corynebacterium. Chemotherapy 59:294–306. doi: 10.1159/000357467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prats-Sanchez I, Soler-Sempere MJ, Sanchez-Hellin V. 2015. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation by Corynebacterium propinquum. Arch Bronconeumol 51:154–155. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez-Aguilar M, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Fernandez-Olmos A, Guisado P, Del Campo R, Quereda C, Canton R, Meseguer MA. 2013. Non-diphtheriae Corynebacterium species: an emerging respiratory pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32:769–772. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motomura K, Masaki H, Terada M, Onizuka T, Shimogama S, Furumoto A, Asoh N, Watanabe K, Oishi K, Nagatake T. 2004. Three adult cases with Corynebacterium propinquum respiratory infections in a community hospital. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 78:277–282. (In Japanese.) doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.78.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furumoto A, Masaki H, Onidzuka T, Degawa S, Yamaryo T, Shimogama S, Watanabe K, Oishi K, Nagatake T. 2003. A case of community-acquired pneumonia caused by Corynebacterium propinquum. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 77:456–460. (In Japanese.) doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.77.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chudnicka A, Koziol-Montewka M. 2003. Characteristics of opportunistic species of the Corynebacterium and related coryneforms isolated from different clinical materials. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med 58:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babay HA, Kambal AM. 2004. Isolation of coryneform bacteria from blood cultures of patients at a University Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 25:1073–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balci I, Eksi F, Bayram A. 2002. Coryneform bacteria isolated from blood cultures and their antibiotic susceptibilities. J Int Med Res 30:422–427. doi: 10.1177/147323000203000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki Y, Matsubara K, Ishihara H, Nigami H, Iwata A, Kawaguchi K, Fukaya T, Kawamura Y, Kikuchi K. 2014. Corynebacterium propinquum as the first cause of infective endocarditis in childhood. J Infect Chemother 20:317–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux V, Drancourt M, Stein A, Riegel P, Raoult D, La Scola B. 2004. Corynebacterium species isolated from bone and joint infections identified by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol 42:2231–2233. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2231-2233.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babay HA. 2001. Pleural effusion due to Corynebacterium propinquum in a patient with squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Saudi Med 21:337–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martins C, Faria L, Souza M, Camello T, Velasco E, Hirata R Jr, Thuler L, Mattos-Guaraldi A. 2009. Microbiological and host features associated with corynebacteriosis in cancer patients: a five-year study. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 104:905–913. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saidani M, Kammoun S, Boutiba-Ben Boubaker I, Ben Redjeb S. 2010. Corynebacterium propinquum isolated from a pus collection in a patient with an osteosynthesis of the elbow. Tunis Med 88:360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura Y, Nakagawa K, Imanishi H, Ozawa T, Tsuruta D, Niki M, Ezaki T. 2014. Case of trichomycosis axillaris caused by Corynebacterium propinquum. J Dermatol 41:467–469. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdolrasouli A, Roushan A. 2013. Corynebacterium propinquum associated with acute, nongonococcal urethritis. Sex Transm Dis 40:829–831. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho BJ, Lee YB. 2002. Infectious keratitis manifesting as a white plaque on the cornea. Arch Ophthalmol 120:1091–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]