Abstract

Performances of the Rapidec Carba NP test (bioMérieux) were evaluated for detection of all types of carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In less than 2 h after sample preparation, it showed a sensitivity and specificity of 96%. This ready-to-use test is well adapted to the daily need for detection of carbapenemase producers in any laboratory worldwide.

TEXT

Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria is growing at an alarming rate (1). In this context, carbapenemase producers are becoming extremely important (2, 3). Rapid detection of carbapenemase producers provides critical information for antibiotic stewardship and rapid implementation of outbreak control measures (3).

Few techniques are available for the rapid identification of carbapenemase producers (4) and include UV spectrophotometry (5), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) technology (6–8), and molecular techniques (9–12). These techniques have overall good sensitivities and specificities but may require trained microbiologists, expensive equipment, and may be time-consuming and expensive. In addition, molecular techniques may fail to detect unknown carbapenemase genes or genes not included in the given gene panel.

A rapid and biochemical detection of carbapenemase production was recently proposed, namely, the Carba NP test, which is based on the detection of the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring of imipenem (13). The Carba NP test has been extensively validated for the detection of carbapenemase producers in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. (13–20), and a slightly modified version of this test (CarbAcineto NP) has been developed for the detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp. (21). Here, we evaluated the performance of the Rapidec Carba NP test (bioMérieux, La Balme-les-Grottes, France) from bacterial cultures and compared its performance to those of the Carba NP test (13) and the CarbAcineto NP test (21).

Performance of the Rapidec Carba NP test compared to that of the Carba NP test. A total of 176 strains were used to evaluate the performance of the Rapidec Carba NP test. They were from various clinical origins (blood culture, urine, sputum, gut flora), of worldwide origin, and isolated from 2010 to 2014. These strains had previously been characterized for their carbapenemase content at the molecular level (Table 1). This strain collection included the most frequently acquired carbapenemases identified worldwide, including those found in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas sp., and Acinetobacter sp. clinical isolates, and also rare carbapenemases. Susceptibility testing was performed by determining MIC values using the Etest (bioMérieux) on Mueller-Hinton agar plates at 37°C, and results were recorded according to U.S. guidelines (CLSI) as updated in 2014 (22). A total of 98 isolates producing all types of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases were included, with 75 carbapenemase-negative strains either carbapenem susceptible (n = 52) or carbapenem resistant (permeability defects) (n = 23) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Features of Gram-negative isolates tested with the Rapidec Carba NP test compared with the Carba NP test

| Species | β-Lactamase contenta | Result of Rapidec Carba NP test at: |

Result of Carba NP test at: |

Imipenem MIC (μg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 2 h | 30 min | 2 h | |||

| Carbapenemase-negative strains | ||||||

| A. baumannii | OXA-66 overexpression | − | − | − | − | 16 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-66 overexpression | − | − | − | − | 4 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-66 low-level expression | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| P. aeruginosa | OXA-28 | − | − | − | − | 2 |

| E. coli | OXA-30 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| E. cloacae | OXA-163 + CTX-M-15 | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| E. coli | ACC-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| K. pneumoniae | ACT-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| P. aeruginosa | OprD mutant, MexAB++, AmpC++ | − | − | − | − | 64 |

| Citrobacter freundii | AmpC + ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 32 |

| E. cloacae | AmpC + ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 128 |

| E. cloacae | AmpC + ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 256 |

| E. coli | AmpC + ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 16 |

| K. pneumoniae | AmpC + ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 32 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 32 |

| E. cloacae | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 64 |

| E. cloacae | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 8 |

| E. coli | AmpC + porin deficiency | + | + | − | − | 8 |

| E. coli | ESAC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 8 |

| Hafnia alvei | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 16 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 32 |

| K. pneumoniae | AmpC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 64 |

| M. morganii | AmpC + porin deficiency | NIb | NI | − | − | 64 |

| Serratia marcescens | ESAC + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| E. aerogenes | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| E. cloacae | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| E. coli | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| K. oxytoca | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| K. pneumoniae | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| K. pneumoniae | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| P. mirabilis | ESBL + porin deficiency | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| E. cloacae | AmpC + TEM-1 + CTX-M-15 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| E. cloacae | AmpC + TEM-1 + OXA-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| A. baumannii | ESAC overexpression | − | − | − | − | 2 |

| A. baumannii | AmpC overexpression | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| P. aeruginosa | AmpC overexpression | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| E. coli | ACC-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| E. coli | CMY-2 | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| A. baumannii | Wild type | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| A. baumannii | Wild type | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| E. cloacae | Wild type | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| E. coli | Wild type | − | − | − | − | <0.06 |

| P. aeruginosa | Wild type | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| P. aeruginosa | BEL-1 | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| P. mirabilis | CMY-2 | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| P. vulgaris | CMY-2 | − | − | − | − | 2 |

| E. coli | CTX-M-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| P. mirabilis | CTX-M-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| E. coli | CTX-M-15 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| K. pneumoniae | CTX-M-15 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| E. cloacae | CTX-M-15 | NI | NI | NI | NI | 0.06 |

| E. coli | CTX-M-15 + SHV-12 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| K. pneumoniae | CTX-M-15 + SHV-12 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| K. pneumoniae | CTX-M-15 + SHV-28 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| C. freundii | CTX-M-3 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| E. aerogenes | CTX-M-3 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| P. aeruginosa | GES-9 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| K. pneumoniae | GES-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| K. pneumoniae | DHA-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| A. baumannii | ESAC | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| A. baumannii | ESAC | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| E. coli | ESAC | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| S. marcescens | ESAC | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| K. pneumoniae | FOX-5 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| A. baumannii | PER-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| E. cloacae | PER-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| A. baumannii | PER-2 | − | − | − | − | 0.5 |

| K. pneumoniae | SHV-2a | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| K. pneumoniae | SHV-38 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| C. freundii | TEM-24 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| E. cloacae | TLA-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| E. coli | VEB-1 + OXA-10 + TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| P. aeruginosa | VEB-1 + OXA-10 + TEM-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 |

| Acinetobacter johnsonii | VEB-1 + SCO-1 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 |

| Carbapenemase-positive strains | ||||||

| P. aeruginosa | FIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | BIC-1 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| P. aeruginosa | GES-2 | − | − | + | − | 16 |

| P. aeruginosa | GES-5 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| E. cloacae | GIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 1 |

| P. aeruginosa | GIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| E. cloacae | IMI-2 | + | + | + | + | 256 |

| S. marcescens | SME-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| P. aeruginosa | SPM-1 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| P. aeruginosa | IMP-1 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| S. marcescens | IMP-1 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| P. aeruginosa | IMP-10 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| P. aeruginosa | IMP-13 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa | IMP-13 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| C. freundii | KPC-2 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 1 |

| E. cloacae | KPC-2 + TEM-1 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 + SHV-1 + TEM-1 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 + SHV-1 + TEM-1 + OXA-9 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| P. aeruginosa | KPC-2 | + | + | + | + | >256 |

| E. coli | KPC-3 + OXA-9 | + | + | + | + | 1 |

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-3 + SHV-11 + TEM-1 + OXA-9 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| A. baumannii | NDM-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| A. baumannii | NDM-1 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| A. baumannii | NDM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| A. baumannii | NDM-2 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| A. baumannii | NDM-1 | − | − | + | + | 16 |

| E. cloacae | NDM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| E. cloacae | NDM-1 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. coli | NDM-1 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. coli | NDM-1 + OXA-1 + TEM-1 + CMY-30 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| E. coli | NDM-1 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | NDM-1 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + OXA-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| K. pneumoniae | NDM-1 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + CMY-16 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| P. mirabilis | NDM-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| P. mirabilis | NDM-1 + OXA-1 + TEM-1 + CMY-16 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| P. aeruginosa | NDM-1 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| E. coli | NDM-4 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + OXA-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| K. pneumoniae | NDM-4 + CTX-M-15 + SHV-11 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| E. coli | NDM-5 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. coli | NDM-7 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-143 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| C. freundii | OXA-162 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. coli | OXA-181 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-181 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + SHV-11 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| E. coli | OXA-204 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + CMY-2 | + | + | + | + | 0.5 |

| E. coli | OXA-204 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + CMY-4 | + | + | + | + | 0.5 |

| P. mirabilis | OXA-204 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 + PER-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 + PER-7 | − | − | − | − | 8 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 + GES-11 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| P. mirabilis | OXA-23 | − | − | − | − | 0.25 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 + NDM-1 | + | + | + | + | >512 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-23 + OXA-40 | + | + | + | + | 512 |

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-232 + CTX-M-15 + OXA-1 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-40 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-40 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| Acinetobacter pittii | OXA-40 | − | − | − | − | 16 |

| C. freundii | OXA-48 + SHV-12 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| E. aerogenes | OXA-48 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| E. aerogenes | OXA-48 + TEM-1 + SHV-12 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. aerogenes | OXA-48 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| E. cloacae | OXA-48 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| E. cloacae | OXA-48 + TEM-1 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. cloacae | OXA-48 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| Enterobacter hormaechei | OXA-48 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| E. coli | OXA-48 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| E. coli | OXA-48 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| E. coli | OXA-48 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| E. coli | OXA-48 + CTX-M-14 | NI | NI | NI | NI | 16 |

| E. coli | OXA-48 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-48 + SHV-28 | + | + | NI | NI | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-48 + SHV-28 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-48 + SHV-1 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| K. pneumoniae | OXA-48 + SHV-11 + SHV-2a + OXA-47 + TEM-1 + OXA-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| S. marcescens | OXA-48 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| S. marcescens | OXA-48 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-58 | + | + | + | + | 32 |

| A. baumannii | OXA-58 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| Acinetobacter haemolyticus | OXA-58 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| E. aerogenes | VIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| E. cloacae | VIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 1 |

| K. pneumoniae | VIM-1 + SHV-5 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| K. pneumoniae | VIM-1 + SHV-12 | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa | VIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| P. aeruginosa | VIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| Pseudomonas putida | VIM-1 | + | + | + | + | 256 |

| C. freundii | VIM-2 + TEM-1 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| P. mirabilis | VIM-2 | + | + | + | + | 2 |

| P. aeruginosa | VIM-2 | + | + | + | + | >256 |

| P. fluorescens | VIM-2 | + | + | + | + | 256 |

| P. putida | VIM-2 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | VIM-2 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| S. marcescens | VIM-2 + CTX-M-15 | + | + | + | + | 64 |

| Citrobacter murliniae | VIM-4 | + | + | + | + | 16 |

| K. pneumoniae | VIM-4 + CTX-M-15 + TEM-1 + SHV-11 | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| P. aeruginosa | VIM-4 | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| P. putida | VIM-5 | + | + | + | + | 256 |

ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; ESAC, AmpC with extended hydrolytic activity toward broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Carbapenemases are indicated in bold.

NI, not interpretable.

Bacterial cultures were grown onto Mueller-Hinton E (MHE) agar plates (bioMérieux). The Rapidec Carba NP test was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. An inoculum corresponding to a full loop (10 μl) of colonies taken from a culture plate is mixed into the cell (the amount of bacteria is critical). Eye reading of the plate is made after 30 min of incubation at 37°C and then after 2 h, if necessary. A positive test corresponded to a red-to-yellow or red-to-orange color change. This eye evaluation was performed blindly by two technicians who did not know about the carbapenemase status of the strains.

The Rapidec Carba NP test showed excellent specificity and sensitivity, allowing reliable detection of known carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp. Detection of the carbapenemase activity was successful for all but four of the tested strains (Table 1), including a single GES-2-producing P. aeruginosa isolate (23), a single OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii isolate, a single OXA-40-producing Acinetobacter pittii isolate, and a single Proteus mirabilis isolate producing a chromosomally encoded OXA-23 (24). These isolates were also all negative according to the home-made Carba NP test (Table 1). The Rapidec Carba NP test showed excellent performance with all bacterial species, including Acinetobacter spp. No carbapenemase activity was detected among A. baumannii strains resistant to carbapenems due to the overexpression of their intrinsic chromosomally encoded and therefore nontransferable OXA-51-like enzyme (OXA-66) (Table 1). In contrast, production of OXA-23 was detected in seven out of nine A. baumannii isolates tested, which is important considering the large dissemination of OXA-23 producers worldwide (25).

False-positive results were obtained with very few isolates and included two A. baumannii isolates overproducing AmpCs (one an extended-spectrum AmpC [ESAC]) (26) and a single Proteus vulgaris isolate producing a plasmid-encoded CMY-2 (known to possess very weak carbapenemase activity [27]).

Interestingly, the OXA-163-producing Enterobacter cloacae isolate gave a negative result, which is in accordance with the fact that this OXA-48 variant is known to lack significant carbapenemase activity (28).

Interpretation of the Rapidec Carba NP test.

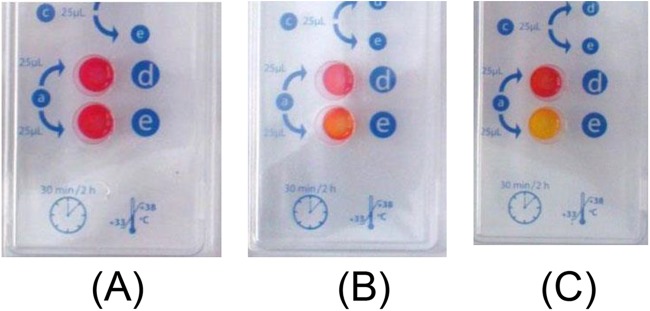

In most cases, positive results obtained with the Rapidec Carba NP test corresponded to a frank color change from red to yellow (Figure 1). For the class A and class B carbapenemase producers, the color change was always obtained in <10 min. For the class D β-lactamases, the color change was obtained in <30 min. Extending the duration of visual inspection to 2 h did not provide any additional value to the test.

FIG 1.

Representative results obtained using the Rapidec Carba NP test on three isolates. The positivity of the reaction must be read in well e, while well d is a control that must be red to validate the test. (A) Negative result (red) obtained when testing an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing K. pneumoniae isolate. (B) Weak result (orange) obtained when testing an OXA-23-producing A. baumannii isolate. (C) Strong result (yellow) obtained when testing an NDM-1-producing E. coli isolate.

Overall, 1.7% of the isolates gave noninterpretable results, meaning that those strains generated an acidification of the reaction regardless of the presence of the carbapenem substrate. Among them, there was a single OXA-48-producing Escherichia coli isolate and a single CTX-M-15-producing E. cloacae isolate. Similarly, noninterpretable results were obtained with those two strains when using the home-made Carba NP test. Another noninterpretable result was obtained with an OXA-48-producing isolate using the Carba NP, but it was interpretable and positive with the Rapidec Carba NP test. Conversely, a noninterpretable result was obtained with the Rapidec Carba NP test but not with the Carba NP when testing a carbapenem-resistant but carbapenemase-negative Morganella morganii isolate overexpressing its chromosomal AmpC and showing permeability defect.

Interestingly, faster results were obtained with some isolates regardless of their carbapenem MIC levels. The fastest results were always obtained with class A carbapenemase producers (most of the time within 5 to 10 min), then with class B carbapenemase producers (10 to 15 min), and followed by class D carbapenemase producers (20 to 30 min).

Performance of the Rapidec Carba NP test for identification of patients colonized with carbapenemase producers.

In order to evaluate whether the Rapidec Carba NP test may be useful for screening carbapenemase producers from colonized patients, stool samples that were negative for carbapenemase-producing bacteria were spiked with several carbapenemase-producing strains (n = 30). An inoculum of 105 CFU/g of each strain was added to each stool sample. An average of ca. 20 mg of spiked stool was tested to simulate the feces quantity of a rectal swab. Spiked stool samples were then cultured onto chromID OXA-48 plates (selection of OXA-48-like producers) (bioMérieux) and chromID Carba plates (selection of all the other carbapenemase producers) (bioMérieux). All colonies tested positive with the Rapidec Carba NP test within 30 min regardless of the species tested. The color of the colonies obtained on the chromogenic screening plates (red, blue, green, etc.) did not interfere with the interpretation of the Rapidec Carba NP test. Neither the sensitivity nor the specificity of the test was modified.

Rapidec Carba NP test and carbapenemase-producing strains presenting a mucoid phenotype.

A special preparation of the lysate was made for mucoid isolates in order to evaluate whether the mucoid phenotype of specific strains might interfere with the results of the Carba NP test. A 10-μl full loop of mucoid colonies was resuspended in 100 μl of suspension solution in an Eppendorf tube in which two 3-mm large glass beads were added (VWR International, Nyon, Switzerland). This solution was vortexed for 1 min, and the 100-μl supernatant was taken as a sample for further testing following the classical protocol as mentioned above. A total of 18 strains were tested, including seven carbapenemase-producing isolates, three carbapenem-resistant but carbapenemase-negative isolates, and 11 wild-type Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates without acquired resistance mechanisms to β-lactams. All carbapenemase-producing isolates tested positive, and no false positivity or noninterpretable results were observed.

In conclusion, the results obtained here highlight that the Rapidec Carba NP test is very sensitive and specific for detection of carbapenemases in clinically significant Gram-negative bacteria. The use of the Rapidec Carba NP test may contribute to the identification of carbapenemase producers and improve infection control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to D. Uldry for technical support. We also thank R. Bonnet for the gift of the OXA-23-positive P. mirabilis isolate and G. M. Rossolini for the gift of the FIM-1-producing P. aeruginosa isolate.

The Rapidec Carba NP kits used for the evaluation were provided by bioMérieux.

An international patent form for the Carba NP test (which included the further development of the CarbAcineto NP test) was filed on behalf of INSERM Transfert (Paris, France).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossolini GM, Arena F, Pecile P, Pollini S. 2014. Update on the antibiotic resistance crisis. Curr Opin Pharmacol 18:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temkin E, Adler A, Lerner A, Carmeli Y. 2014. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: biology, epidemiology, and management. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1323:22–42. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. 2012. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol Med 18:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dortet L, Bréchard L, Cuzon G, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2014. Strategy for rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2441–2445. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01239-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernabeu S, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Spectrophotometry-based detection of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 74:88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hrabák J, Walková R, Studentová V, Chudácková E, Bergerová T. 2011. Carbapenemase activity detection by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol 49:3222–3227. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00984-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kempf M, Bakour S, Flaudrops C, Berrazeg M, Brunel JM, Drissi M, Mesli E, Touati A, Rolain JM. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. PLoS One 7:e31676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee W, Chung HS, Lee Y, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee K, Chong Y. 2013. Comparison of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry assay with conventional methods for detection of IMP-6, VIM-2, NDM-1, SIM-1, KPC-1, OXA-23, and OXA-51 carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 77:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. 2011. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM, Turton JF, Ward ME, Brown S, Amyes SG, Livermore DM. 2006. Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents 27:351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofko M, Mischnik A, Kaase M, Zimmermann S, Dalpke AH. 2014. Detection of carbapenemases by real-time PCR and melt curve analysis on the BD Max system. J Clin Microbiol 52:1701–1704. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00373-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuzon G, Naas T, Bogaerts P, Glupczynski Y, Nordmann P. 2012. Evaluation of a DNA microarray for the rapid detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (TEM, SHV and CTX-M), plasmid-mediated cephalosporinases (CMY-2-like, DHA, FOX, ACC-1, ACT/MIR and CMY-1-like/MOX) and carbapenemases (KPC, OXA-48, VIM, IMP and NDM). J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1865–1869. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dortet L. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1503–1507. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.120355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp. J Clin Microbiol 50:3773–3776. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01597-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tai AS, Sidjabat HE, Kidd TJ, Whiley DM, Paterson DL, Bell SC. 2015. Evaluation of phenotypic screening tests for carbapenemase production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Microbiol Methods 111:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkova N, Babalova M, Sokolova J, Krcmery V. 2015. First report of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1-producing strains in Slovakia. Microb Drug Resist 21:117–120. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osterblad M, Hakanen AJ, Jalava J. 2014. Evaluation of the Carba NP test for carbapenemase detection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7553–7556. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02761-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adler A, Hussein O, Ben-David D, Masarwa S, Navon-Venezia S, Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y, Post-Acute-Care Hospital Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Working Group. 2015. Persistence of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 as the predominant clone of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in post-acute-care hospitals in Israel, 2008-13. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:89–92. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yusuf E, Van Der Meeren S, Schallier A, Piérard D. 2014. Comparison of the Carba NP test with the Rapid CARB Screen kit for the detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:2237–2240. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majewski P, Wieczorek P, Sacha PT, Frank M, Juszczyk G, Ojdana D, Kłosowska W, Wieczorek A, Sieńko A, Michalska AD, Hirnle T, Tryniszewska EA. 2014. Emergence of OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter cloacae ST89 infection in Poland. Int J Infect Dis 25:107–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dortet L, Poirel L, Errera C, Nordmann P. 2014. CarbAcineto NP test for rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol 52:2359–2364. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00594-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 24th informational supplement. CLSI M100-S24. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poirel L, Weldhagen GF, Naas T, De Champs C, Dove MG, Nordmann P. 2001. GES-2, a class A beta-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa with increased hydrolysis of imipenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2598–2603. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2598-2603.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnet R, Marchandin H, Chanal C, Sirot D, Labia R, De Champs C, Jumas-Bilak E, Sirot J. 2002. Chromosome-encoded class D beta-lactamase OXA-23 in Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:2004–2006. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.2004-2006.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mugnier PD, Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2010. Worldwide dissemination of the blaOXA-23 carbapenemase gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg Infect Dis 16:35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Nordmann P, Ronco E, Poirel L. 2010. Extended-spectrum cephalosporinase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3484–3488. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00050-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahyot S, Broutin I, de Champs C, Guillon H, Mammeri H. 2013. Contribution of asparagine 346 residue to the carbapenemase activity of CMY-2 β-lactamase. FEMS Microbiol Lett 345:147–153. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel L, Castanheira M, Carrër A, Rodriguez CP, Jones RN, Smayevsky J, Nordmann P. 2011. OXA-163, an OXA-48-related class D β-lactamase with extended activity toward expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2546–2551. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]