Abstract

Prospective registration of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) represents the best solution to reporting bias. The extent to which oral health journals have endorsed and complied with RCT registration is unknown. We identified journals publishing RCTs in dentistry, oral surgery, and medicine in the Journal Citation Reports. We classified journals into 3 groups: journals requiring or recommending trial registration, journals referring indirectly to registration, and journals providing no reference to registration. For the 5 journals with the highest 2012 impact factors in each group, we assessed whether RCTs with results published in 2013 had been registered. Of 78 journals examined, 32 (41%) required or recommended trial registration, 19 (24%) referred indirectly to registration, and 27 (35%) provided no reference to registration. We identified 317 RCTs with results published in the 15 selected journals in 2013. Overall, 73 (23%) were registered in a trial registry. Among those, 91% were registered retrospectively and 32% did not report trial registration in the published article. The proportion of trials registered was not significantly associated with editorial policies: 29% with results in journals that required or recommended registration, 15% in those that referred indirectly to registration, and 21% in those providing no reference to registration (P = 0.05). Less than one-quarter of RCTs with results published in a sample of oral health journals were registered with a public registry. Improvements are needed with respect to how journals inform and require their authors to register their trials.

Keywords: clinical trials as topic, editorial policies, publication bias, registries, randomized controlled trial, split-mouth trial

Background

Decisions about which treatment is best are driven by the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews. The conclusions of a systematic review may be misleading, however, when the relevant body of evidence is biased. In fact, researchers and sponsors tend not to make public all results of clinical trials or specific outcomes or analyses on the basis of the direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of the results (Montori et al. 2008). Negative results are less likely to be reported, and, as a consequence, systematic reviews are skewed toward the positive (Dwan et al. 2008).

Prospective registration of clinical trials represents the best solution to these reporting biases. Investigators are encouraged to register their trials in a public registry. In fact, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has made registration a requirement for publication in their journals since September 2005. Registration does not guarantee that trial results will be ultimately published, but it is a key factor in reducing waste in research (Ioannidis et al. 2014).

To our best knowledge, no study has assessed to what extent trial registration is implemented in the field of oral health. The likelihood of trial registration may vary among dentistry journals because some journals have adopted editorial policies for several years to enforce trial registration, whereas others have not (Giannobile 2012; Pihlstrom 2012). Trial registration may also vary by study design. In particular, split-mouth trials are popular in oral health research but may be registered less frequently than parallel-arm trials. In fact, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) and ICMJE’s clinical trial registration policies, and their definition of clinical trials for the purposes of registration, do not explicitly cover split-mouth trials (ICMJE 2014; WHO 2014).

Our objective was to assess the endorsement of trial registration in author instructions of oral health journals and to evaluate how many RCTs with results published in oral health journals had been registered in trial registries. A secondary objective was to compare the registration of split-mouth and parallel-arm RCTs.

Methods

Endorsement of Trial Registration

We identified all journals indexed in the subject category “dentistry, oral surgery and medicine” in the 2012 Journal Citation Reports (JCR; Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Knowledge, 2012). Two independent authors selected journals publishing RCTs. We excluded journals reporting fundamental research, research methods, reviews, or commissioned articles only. We also excluded journals publishing manuscripts not written in English.

For each journal, two authors independently and in duplicate examined the journal’s website section on author instructions for submitting manuscripts in December 2013. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. We categorized each journal into 3 prespecified groups: 1) journals requiring or recommending trial registration, 2) journals referring indirectly to trial registration without editorial advice, or 3) journals providing no reference to trial registration (Appendix, “Details” section).

Registration of RCTs

Selection of RCTs

We selected the 5 journals with the highest impact factor (IF) from each of the 3 groups determined previously. We scanned the tables of contents of these journals to identify all RCTs with results published in 2013. We considered a clinical trial as randomized if the authors referred to treatment allocation as randomized or randomly allocated in the title, abstract, or full-text article. Trials recruiting patients before 2006 were excluded because the 2004 ICMJE statement had defined July 1, 2005, as a key date for prospective trial registration. Two reviewers selected articles independently and in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Characteristics of RCTs

For each RCT, two authors independently and in duplicate assessed the following characteristics. We noted whether an institutional review board (IRB) or ethics committee had approved the RCT protocol. We assessed the study design (i.e., parallel-arm, cluster, crossover, or split-mouth). We classified a trial as having a split-mouth design if the authors clearly described “split mouth” in the title and abstract. If the design was not clear, we systematically screened the methods section to identify split-mouth RCTs as trials with experimental and control interventions randomly allocated to different areas in the oral cavity (e.g., teeth or quadrants) (Antczak-Bouckoms et al. 1990; Pandis et al. 2013; Ramfjord et al. 1968).

We assessed the risk of bias associated with sequence generation and allocation concealment using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias (RoB) tool (Higgins and Altman 2008; Higgins et al. 2011). Each RCT was assigned an overall RoB assessment: low risk (low for the 2 domains), high risk (high for at least 1 domain), or unclear risk (unclear for at least 1 domain).

Finally, we assessed whether each RCT had been registered in a trial registry. We searched for trial registration numbers in the published reports. If trial registration was not reported, we searched the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) by using relevant key words based on the title, authors’ names or participants, experimental intervention, and comparator (Grobler et al. 2008). For registered trials, we assessed whether the registration was prospective or retrospective, that is, before or after the date of first enrollment (Appendix, “Details” section).

Statistical Analysis

We assessed whether the proportions of registered trials were associated with editorial policies or with trial design. First, we used chi-square tests to test the significance of the differences among all groups. Second, we calculated pairwise comparisons between pairs of proportions with correction for multiple testing, as well as the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the difference in proportions (Agresti et al. 2008). Analyses involved use of the R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Endorsement of Trial Registration

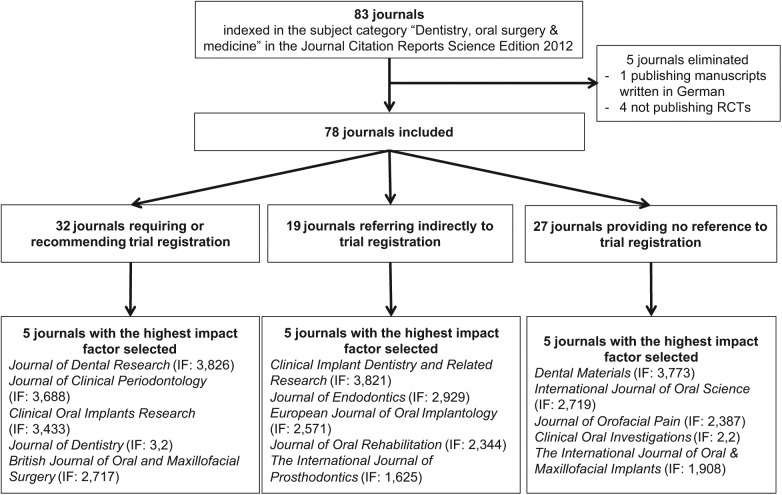

We identified 83 journals (Figure 1). We excluded 4 journals publishing no RCTs (Appendix Table 1) and 1 journal (Implantologie, IF 0.169) publishing manuscripts in German. We assessed 78 journals with 2012 IFs ranging from 0.167 to 3.826.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included journals.

In all, 32 (41%) journals required or recommended trial registration, 19 (24%) referred indirectly to trial registration, and 27 (35%) provided no reference to trial registration. Journals with high IFs were more likely to require or recommend trial registration. For a detailed listing of journals in each group, see the Appendix (Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Registration of RCTs

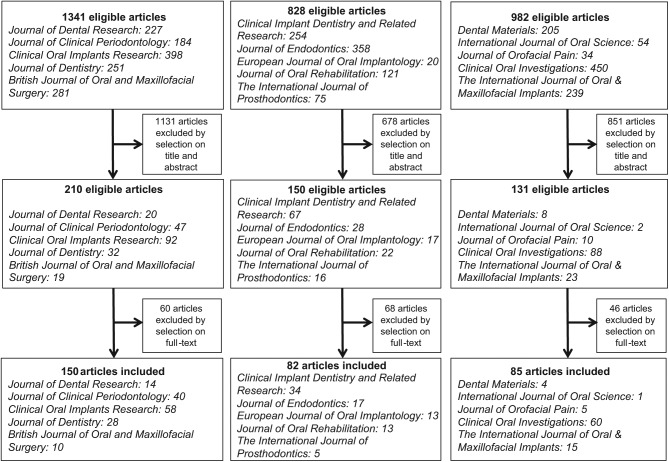

We identified 317 (10%) RCTs with results published in 2013 in the 5 journals with the highest IF from each group, among 3,151 articles searched (Figure 2). The characteristics of included studies are in the Table. Details are in the Appendix (Table 5). An IRB or ethics committee had approved the RCT protocol for 85% of published reports. In total, 68% of reports described parallel-arm studies and 21% split-mouth studies. The risk of selection bias was considered low for only 61 (19%) RCTs. For 253 reports (80%), the risk of bias was unclear.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of included articles.

Table.

Characteristics of Included Articles

| Characteristics of RCTs | Number of RCTs (%) n = 317 |

|---|---|

| Trial registration | |

| Required or recommended | 150 (47%) |

| Referred indirectly | 82 (26%) |

| Not referred | 85 (27%) |

| Design | |

| Parallel-arm | 217 (68%)* |

| Split-mouth | 65 (21%)* |

| Crossover | 37 (17%) |

| Cluster | 7 (2%) |

| Ethics committee reported | 270 (85%) |

| Risk of selection bias | |

| Low risk | 61 (19%) |

| High risk | 3 (1%) |

| Unclear | 253 (80%) |

| Trial registration | 73 (23%) |

| Trial register number reported in the published article | 50 |

| Trial register number not reported in the published article | 23 |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | 52 (71%) |

| ISRCTN | 10 (14%) |

| Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry | 4 (5%) |

| European Community Clinical Trial System | 2 (3%) |

| Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials | 2 (3%) |

| German Clinical Trials Register | 2 (3%) |

| Dutch Trial Registration | 1 (1%) |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; ISRCTN: International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register.

3 split-mouth and parallel-arm; 6 split-mouth crossover.

Registration of RCTs

We found 73 (23%) RCTs registered in a clinical trials registry: 50 specified the registration number in the corresponding published report, and we identified 23 additional trials after searching the ICTRP. At least 1 RCT was registered in all selected journals except 1 (which had 13 RCTs). Only 1 journal (with 14 RCTs) had all RCTs registered. Most of the trial protocols were registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (52/73 [71%]) or the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Register (10/73 [14%]). Among the 73 registered trials, 13 (9%) were registered prospectively and 60 (91%) were registered retrospectively (among which 17 were registered within 6 months of the first enrollment).

Differences in Registration of RCTs by Editorial Policies

Of the 150 RCTs with results published in journals that required or recommended trial registration, 43 (29%) were registered; of the 82 RCTs in journals that referred indirectly to trial registration, 12 (15%) were registered; and, of the 85 RCTs in journals that did not provide reference to trial registration, 18 (21%) were registered (Appendix Table 6). The proportion of trials registered was not significantly associated with the editorial policy (P = 0.05 among the 3 groups). We found no significant difference between journals that required or recommended trial registration and those that referred indirectly to trial registration (difference 15%; 95% CI, 0 to 26%; P = 0.08) or those that did not provide references to trial registration (difference, 8%; 95% CI, −6 to 21%; P = 0.54), nor between journals that referred indirectly to trial registration and those that did not provide references to trial registration (difference, −6%; 95% CI, −21 to 8%; P = 0.54).

Differences in Registration of RCTs by Study Design

Of the 217 RCTs with a parallel-arm design, 49 (23%) were registered. Of the 65 RCTs with a split-mouth design, 11 (17%) were registered. Of the 37 RCTs with a crossover design, 8 (22%) were registered. Of the 7 RCTs with a cluster design, all were registered (Appendix Table 7). The proportion of trials registered was significantly associated with trial design (chi-square P value < 0.001) because cluster RCTs were more frequently registered than other designs. There were no statistically significant differences, however, between other designs. In particular, the difference in proportion between parallel-arm and split-mouth RCTs was 6% (95% CI, −10 to 18%; P = 1.00).

Discussion

Our study found that 41% of the selected oral health journals required or recommended trial registration in the author guidelines. Only 23% of RCTs were registered in a trial registry; among those, 91% were registered retrospectively and 32% did not report trial registration in the published article. There was no significant difference between journals that required or recommended trial registration and others. Finally, there was no significant difference in the proportion of trials registered between parallel-arm and split-mouth RCTs.

The level of endorsement and compliance with trial registration varied and was generally low in oral health journals. Ensuring trial registration should concern journal editors and also researchers, research institutions, funders, sponsors, and ethics committees, who share the responsibility of transparency in health research (De Angelis et al. 2004). Most registered trials were registered retrospectively. This is probably better than no registration at all, but the retrospective registration and the reason for it should be explicit in the article reporting the trial results. Our findings reflect the fact that trials that did not fulfill prospective registration were not rejected. One potential reason was to ensure that the oral health community has access to the results of these trials. Oral health journals should, however, stress that prospective trial registration (prior to subject enrollment) is essential because retrospective registration (after subject enrollment has begun) defeats one of the main purposes of trial registration, which is to prevent or minimize selective reporting of positive results.

We also found that trial registration numbers were underreported in oral health publications. They should be included in all reports of RCTs for easier cross-checking of published results with registry entries. Peer reviewers and authors of systematic reviews would be able to check that the trial was conducted and reported as intended and assess the risk of bias from selective outcome reporting.

In a previous meta-epidemiological study, we found that split-mouth trials contributed half of the evidence in meta-analyses of oral health research (Smaïl-Faugeron et al. 2014). These results support the use of all available evidence in systematic reviews, including that from split-mouth and parallel-arm RCTs. Hence, researchers should register both study designs. In our sample, 17% of split-mouth trials were registered, and so there is room for improvement. Of note, we cannot capture the element of split-mouth design in ClinicalTrials.gov because only “single group,” “parallel,” “crossover,” or “factorial” study designs are proposed. In addition, only 40 studies were retrieved when we searched for “split-mouth.” ClinicalTrials.gov is the most prominent public trial registry, so the inclusion of the split-mouth design may improve the registration of split-mouth trials.

Our results are similar to those of previous studies in general or specialty medicine studies (Wager and Williams 2013) (Appendix Table 8). The proportion of journals endorsing trial registration ranged from 21% to 62%, and the proportion of trials registered from 20% to 72%.

Our study has some limitations. First, the inclusion of only English-language journals may limit generalization of the results to other journals; however, we eliminated only one journal in German. Second, some journals surveyed do require registration but did not mention this on their website. All accessible material was assessed, but we did not retrieve instructions that could be viewed only as part of the manuscript submission process. Moreover, we assessed the journal websites in December 2013, and they may not have reflected the author instructions at the time that articles selected in our study sample were submitted. Third, we selected a sample of trials in the 15 journals with the highest IFs, so registration rates could differ from those in other journals with lower IFs. Some journals with lower IFs may publish more RCTs, and it would be interesting to expand our sample to include a larger number of trials and to assess how our findings vary. Finally, we did not assess the trend in publication throughout the years because we selected RCTs with results published in 2013 only. Information on the trial registration reporting trend in oral health journals would help in understanding how the oral health research community is responding to the need for prospective trial registration.

In conclusion, less than one-quarter of RCTs with results published in a sample of oral health journals were registered with a public registry. Improvements are needed with respect to how oral health journals inform and require their authors to register their trials.

Author Contributions

V. Smaïl-Faugeron, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted the manuscript; H. Fron-Chabouis, P. Durieux, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Smales (BioMedEditing, Toronto, Canada) for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors received no financial support and declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Agresti A, Bini M, Bertaccini B, Ryu E. 2008. Simultaneous confidence intervals for comparing binomial parameters. Biometrics. 64:1270–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antczak-Bouckoms AA, Tulloch JF, Berkey CS. 1990. Split-mouth and cross-over designs in dental research. J Clin Periodontol. 17(7 Pt 1):446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. ; International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. 2004. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Lancet. 364:911–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan AW, Cronin E, et al. 2008. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS One. 3:e3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannobile WV. 2012. Dentistry, oral health, and clinical investigation. J Dent Res. 91(7 Suppl):3S–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobler L, Siegfried N, Askie L, Hooft L, Tharyan P, Antes G. 2008. National and multinational prospective trial registers. Lancet. 372:1201–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Altman D. 2008. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [accessed 28 July 2014]. http://www.cochrane.org/handbook

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICMJE. 2014. Journals following the ICMJE recommendations [accessed 28 July 2014]. http://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/

- Ioannidis JP, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, et al. 2014. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 383:166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISI Web of Knowledge. 2012. Journal citation reports. New York: Thomson Reuters; [accessed 28 July 2014]. http://wokinfo.com/products_tools/analytical/jcr/ [Google Scholar]

- Montori V, Ioannidis J, Guyatt G. 2008. Reporting bias. In: Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade M, Cook D, editors. User’s guide to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. New York (NY): The McGraw-Hill Companies; p 543–554. [Google Scholar]

- Pandis N, Walsh T, Polychronopoulou A, Katsaros C, Eliades T. 2013. Split-mouth designs in orthodontics: an overview with applications to orthodontic clinical trials. Eur J Orthod. 35:783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlstrom B. 2012. Public registration of clinical trials: good for patients, good for dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 143:9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramfjord SP, Nissle RR, Shick RA, Cooper H., Jr 1968. Subgingival curettage versus surgical elimination of periodontal pockets. J Periodontol. 39:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaïl-Faugeron V, Fron-Chabouis H, Courson F, Durieux P. 2014. Comparison of intervention effects in split-mouth and parallel-arm randomized controlled trials: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 14:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager E, Williams P; Project Overcome Failure to Publish Negative Findings Consortium. 2013. «Hardly worth the effort»? Medical journals’ policies and their editors’ and publishers’ views on trial registration and publication bias: quantitative and qualitative study. BMJ. 347:f5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2014. International clinical trials registry platform [accessed 28 July 2014]. http://www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.