The United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) will end in 2015 and will be replaced by Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The MDGs were successful in bringing national governments together and highlighted the importance of health in human development. However, the MDGs had a very specific disease focus, did not incorporate noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), and failed to have a significant effect on reducing health inequalities within and between countries (Save the Children 2012; UNSDSN 2013). The new SDGs will provide a framework for integrating action across multiple sectors to enable human development to proceed in a manner that optimizes the use of limited resources without endangering sustainability. In recent months, consultations and high-level panel meetings have deliberated on how health can be included in the SDGs and what would be appropriate indicators for any new global health goal(s) (Save the Children 2012; United Nations 2013; UNSDSN 2013). One common theme emerging from these consultations is universal health coverage (UHC), either as a specific health goal or as a means of achieving health gains in the post-2015 SDGs.

The call for UHC has grown stronger over the past decade. The Rio +20 summit on sustainable development recognized UHC for enhancing “health, social cohesion and sustainable human and economic development and a precursor to strengthen national health systems” (United Nations 2012). Dr Margaret Chan, the director general of World Health Organization (WHO), has called UHC the “the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer” (Holmes 2012), and Dr Jim Yong Kim, the president of the World Bank, has called for the global achievement of UHC “within this generation” (World Bank 2013). A unique opportunity currently exists to influence global health policy and ensure that oral health is recognized as a key public health priority and is integrated into the emerging UHC policy agenda.

Definition and Concept of Universal Health Coverage

WHO (2010) has defined UHC as “ensuring that all people can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.”

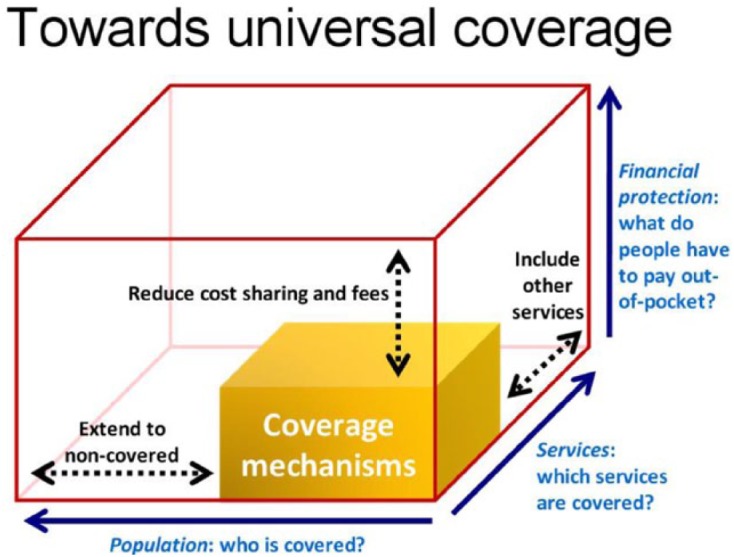

The main concepts of UHC include 1) population coverage, 2) range of health services provided, and 3) out-of-pocket expenditure (Figure).

Figure.

The 3 dimensions of universal health coverage.

The concept of UHC is not new. It began to evolve in Europe with reforms introduced by Bismarck in Germany in the 19th century and the introduction of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom in 1946 (Giedion et al. 2013). The WHO constitution in 1948 and the Alma-Ata Declaration in 1978 both indirectly stressed UHC as an important tool to achieve “Health for All.” However, it is only in the past decade that the concept has received much greater recognition. A resolution at the 58th World Assembly in 2005 encouraged the countries of the world to embed UHC in their health systems, and the World Health Report (2010) proposed improved financing for health care to achieve this goal (WHO 2010).

Oral Health: Moving from Apathy to Action

Oral health is important for overall health, well-being, and quality of life and shares common biological, behavioral, and psychosocial risk factors with various other NCDs. As with other chronic diseases, there are widespread oral health inequalities not only in oral health outcomes but also in access to oral health care. The burden of oral diseases has a disproportionate impact on the poorer, less educated members of society. Oral diseases are the fourth most expensive disease to treat (Petersen 2008). Out-of-pocket expenditure for dental treatment is a major drain on limited personal resources for the most vulnerable and increases risks of poverty and further illness. In many parts of the world, particularly in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), coverage, availability, and access to oral health care—including early diagnosis, prevention, and basic treatment—are grossly inadequate or completely lacking.

Oral health has often been neglected in national health plans and global health strategies (Benzian et al. 2011). The past decade has seen an increasing recognition of the global importance of NCDs and the need for an integrated policy response within national health programs. However, oral diseases have frequently not been included within the NCD policy agenda at either a national (particularly in LMICs) or global level. The UN Health Assembly Resolution of 2013 highlighted cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory illnesses as major NCDs but importantly also acknowledged that oral, renal, and eye diseases shared the same risk factors and determinants (United Nations 2011). Building on this statement, it is of paramount importance that the oral health community ensures that oral diseases are included in the emerging UHC debate and policy formulation.

Some countries across the world have adopted their own versions of universal oral health care. For example, Austria, Denmark, Germany, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Mexico are providing basic dental care services through state-sponsored health insurance schemes funded through general taxation mechanisms. Basic dental care services are provided through a mix of subsidized private practitioners and state-funded health services in countries such as Greece, Turkey, and Finland (Paris et al. 2010). However, the dental services provided through country-specific universal oral health care mechanisms vary in their level of coverage, and there are various challenges in evaluating these schemes across different countries. These challenges include diverse definitions, and conceptual models for universal oral health care delivery exist in different countries, with different metrics used for measuring national as well as global progress toward universal oral health care. In addition, the narrow interpretation of UHC as just provision of health care excluding action on the social determinants of health inequalities and an apprehension that a “universal” program may dilute the priority accorded to the needs of the poor may permit others to benefit in a disproportionate manner through better access and negotiating power.

Toward Universal Oral Health Care

The advocacy case for the integration of oral health into the emerging UHC framework will need to address the following:

-

The Epidemiological Argument:

Untreated tooth decay is the most common condition affecting human beings. Close to 4 billion people worldwide suffer from untreated oral conditions.

Disability caused by severe tooth loss is larger than that caused by moderate heart failure.

An average of 224 y per 100,000 people are living with disability due to oral diseases (Marcenes et al. 2013).

-

The Economic Argument:

Oral diseases are both a cause and consequence of poverty.

They have a negative impact on educational and employment opportunities.

There are, however, cost-effective treatments and strategies available (“Best Buys”).

-

The Rights Argument:

The voice of patients and civil society needs to be heard, as has been achieved in the fields of HIV/AIDS and tobacco control.

-

Interlinking with Other Pillars of Sustainable Development:

To achieve oral health goals, health systems also need to be supported by enabling actions in other sectors, including education, food systems, improved nutrition, hygiene, and urban design.

-

Coalitions:

The oral health profession needs to look beyond itself and develop alliances with other professional groups advocating for issues that are of common interest for public health.

Oral health systems across the globe should overcome certain challenges for ensuring the availability of equitable, affordable, and accessible oral health services for all. These challenges include a) serious shortages of appropriately trained dental personnel; b) inadequate outreach to rural and other underserved populations; c) treatment costs that are too high for many poor and marginalized people; d) barriers such as inadequate transport and lack of appropriate technologies; e) isolation of oral health services from the broader health system, especially among LMICs; and f) limited adoption of prevention and oral health promotion. These barriers make it difficult for vulnerable groups of people, including the poor, ethnic minorities, and the disabled, to access fair and equitable oral health care.

These challenges could be overcome by adopting a broader comprehensive vision of UHC in oral health care systems nationally, as well as globally. While health financing is a critical component, the broader mandate of an oral health system has to be stated in terms of the services that are ensured to the whole population through UHC. These include promotive, preventive, curative, palliative, and rehabilitative services, as well as other health-enabling public services such as water, sanitation, and environment. Health-promoting policies in other sectors, addressing the broad social determinants of health, also need to be coupled with UHC.

In conclusion, a unique window of opportunity now exists to influence global health policy. Oral health is often neglected and marginalized in health policy developments. The International Association for Dental Research (IADR), Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI), WHO, and national dental associations must collectively lobby to ensure that oral health is recognized as a key public health priority and is integrated into the emerging universal health coverage policy agenda. This will call for effective advocacy, based on sound evidence, for responsive, integrated health systems to improve oral health care. The adoption of UHC has important implications for dental research. In line with the IADR-GOHIRA® agenda, greater emphasis needs to be placed on exploring the determinants of oral health inequalities and evaluating interventions to promote population oral health and improve quality of care. In addition, more research is needed to assess the economic burden and impact of oral diseases, as well as the cost-effectiveness of both treatment and preventive interventions. This commitment to achieving universal oral health coverage should permeate the other health and development goals that are being proposed for post-2015 SDGs, so that oral health is seen as an enabler of accelerated and equitable development for attainment of other goals.

Footnotes

The authors received no financial support and declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Benzian H, Hobdell M, Holmgren C, Yee R, Monse B, Barnard JT, van Palenstein Helderman W. 2011. Political priority of global oral health: an analysis of reasons for international neglect. Int Dent J. 61(3):124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedion U, Andres Alfonso E, Diaz Y. 2013. The impact of universal coverage schemes in the developing world: a review of the existing evidence. Washington, DC: World Bank; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/Images/IMPACTofUHCSchemesinDevelopingCountries-AReviewofExistingEvidence.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D. 2012. Margaret Chan: committed to universal health coverage. Lancet. 380(9845):879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, Murray CJ. 2013. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 92(7):592–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris V, Devaux M, Wei L. 2010. Health Systems Institutional Characteristics: a survey of 29 OECD countries. OECD Health Working Papers, No. 50. Paris: OECD Publishing; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. https://www.wbginvestmentclimate.org/toolkits/public-policy-toolkit/upload/OECD-Survey.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen PE. 2008. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health—World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 58(3):115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children. 2012. Ending poverty in our generation: Save the Children’s vision for a post-2015 framework. London: Save the Children; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://www.savethechildren.org/atf/cf/%7B9def2ebe-10ae-432c-9bd0-df91d2eba74a%7D/ENDING_POVERTY_IN_OUR_GENERATION_AFRICA_LOW_RES_US_VERSION.PDF [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2011. Draft political declaration of the high-level meeting on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. New York: United Nations; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/pdf/NCD_draft_political_declaration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2012. Report of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://www.uncsd2012.org/content/documents/814UNCSDREPORTfinalrevs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2013. A new global partnership: eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development. New York: United Nations; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://www.un.org/sg/management/pdf/HLP_P2015_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UNSDSN. 2013. Health in the framework of sustainable development: technical report for the post 2015 Sustainable Development Agenda. New York: UNSDSN; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://unsdsn.org/resources/publications/health-in-the-framework-of-sustainable-development/ [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2013. President of the World Bank speech to the World Health Assembly May 21 2013. Washington, DC: World Bank; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2013/05/21/world-bank-group-president-jim-yong-kim-speech-at-world-health-assembly [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2010. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; [accessed 2014 Dec 4]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/whr/2010/9789241564021_eng.pdf?ua=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]