Abstract

Purpose.

Pathological neovessel formation impacts many blinding vascular eye diseases. Identification of molecular signatures distinguishing pathological neovascularization from normal quiescent vessels is critical for developing new interventions. Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1) is a transcription factor important in tumor and pulmonary angiogenesis. This study investigated the potential role of TWIST1 in modulating pathological ocular angiogenesis in mice.

Methods.

Twist1 expression and localization were analyzed in a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR). Pathological ocular angiogenesis in Tie2-driven conditional Twist1 knockout mice were evaluated in both OIR and laser-induced choroidal neovascularization models. In addition, the effects of TWIST1 on angiogenesis and endothelial cell function were analyzed in sprouting assays of aortic rings and choroidal explants isolated from Twist1 knockout mice, and in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells treated with TWIST1 small interfering RNA (siRNA).

Results.

TWIST1 is highly enriched in pathological neovessels in OIR retinas. Conditional Tie2-driven depletion of Twist1 significantly suppressed pathological neovessels in OIR without impacting developmental retinal angiogenesis. In a laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model, Twist1 deficiency also resulted in significantly smaller lesions with decreased vascular leakage. In addition, loss of Twist1 significantly decreased vascular sprouting in both aortic ring and choroid explants. Knockdown of TWIST1 in endothelial cells led to dampened expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and decreased endothelial cell proliferation.

Conclusions.

Our study suggests that TWIST1 is a novel regulator of pathologic ocular angiogenesis and may represent a new molecular target for developing potential therapeutic treatments to suppress pathological neovascularization in vascular eye diseases.

Keywords: angiogenesis, retinopathy, TWIST1

TWIST1 is highly enriched in pathological retinal neovessels in mice. Conditional depletion of Twist1 in Tie2-expressing vascular endothelial cells significantly suppresses pathological ocular angiogenesis in mouse models, suggesting TWIST1 as a novel regulator of angiogenesis in eye diseases.

Introduction

Proliferative neovascularization (NV) is a major pathological feature of blinding vascular eye diseases. These include retinopathy of prematurity, diabetic retinopathy, and neovascular age-related macular degeneration, which are leading causes of vision loss in children, working-age adults, and the elderly in the developed world.1–4 Pathological neovessels in these diseases differ from normal quiescent vessels in both morphology and function. They are highly proliferative with increased vascular permeability, which leads to exudates, hemorrhage, and retinal detachment.5 Defining the molecular pathways distinguishing pathological NV from normal blood vessels is critical for the development of targeted therapies to control these blinding diseases.6,7

Our previous study identified a novel transcription factor, Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1), important for pulmonary vascular integrity.8 This finding led us to hypothesize that TWIST1 may contribute to vascular pathologies in retinopathy as well. TWIST1 is a basic helix-loop-helix (HLH) domain-containing transcription factor and was originally identified in Drosophila by the presence of twisted torsos in embryos that lacked the Twist1 gene.9,10 In humans, TWIST1 is located on chromosome 7p21-p22, and its heterozygous mutations are responsible for autosomal dominant Saethre-Chotzen syndrome, one of the most common craniosynostosis syndromes.11–13 TWIST1 is a critical marker and regulator of epithelial–mesenchymal transition, a process that is crucial for embryonic development and tumor progression. TWIST1 controls mammalian embryonic development including limb budding and cranial neural tube closure,14 and regulates many other biological processes including osteoblast differentiation, tumor growth, metastasis, and drug resistance.15–17 These diverse functions of TWIST1 are achieved through transcriptional regulation of its target genes by recognizing a consensus Enhancer-box (CANNTG) motif on the promoter region of target genes to influence their transcription.18

The importance of TWIST1 in regulating the angiogenic process is demonstrated by previous work in normal and tumor angiogenesis.14,17,19 Knockdown of Twist1 impacts embryonic vascular growth in Xenopus,20 and it is suggested that TWIST1 promotes tumor angiogenesis through promoting secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or mediating chemoattractant chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)-dependent macrophage recruitment.19,21,22 Recently we found that in the lung, TWIST1 controls vascular integrity,8 which is also compromised in vascular eye diseases. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that TWIST1 may also impact pathological NV in the eye.

In the present study, we investigated the functional role of TWIST1 in pathological ocular angiogenesis in mice. Since systematic deletion of Twist1 is embryonically lethal,23,24 we generated conditional knockout mice lacking Twist1 in Tie2-expressing cells. These mice were evaluated in a well-established mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) with pathological retinal NV,25 and also in a laser-induced choroid neovascularization (CNV) model.26 We found significant upregulation and localization of TWIST1 in pathological neovessels in OIR. Conditional depletion of Twist1 significantly dampened pathological NV in both OIR and laser-induced CNV models. Mechanistically we found that this proangiogenic effect of Twist1 may be mediated in part through direct promotion of vascular sprouting and endothelial cell proliferation by regulating vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (Vegfr2) levels. TWIST1 may therefore represent a novel marker for pathological retinal NV and play a significant role in regulation of pathological angiogenesis in vascular eye diseases.

Methods and Materials

Animals

These studies adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Boston Children's Hospital. Twist1flox/flox mice were generated as described previously.8 Tie2-Cre-expressing C57BL/6 mice (stock no. 004128) and ROSA mT/mG reporter mice (stock no. 007576) were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All other experiments were performed in C57BL/6J mice (stock no. 000664; Jackson Laboratory) unless otherwise specified.

Oxygen-Induced Retinopathy, Retina Dissection, Staining, and Imaging

The oxygen-induced retinopathy mouse model was conducted as previously reported.25,27,28 Briefly, to induce retinopathy, mouse pups with nursing mothers were exposed to 75% ± 3% oxygen from postnatal day (P)7 to P12 (phase I: vaso-obliteration) and returned to room air until P17 (phase II: neovascularization).25,27 In phase I, central retinal vessel loss is induced due to the high concentration of oxygen exposure; in phase II, vessel loss promotes stabilization of hypoxia-induced factors (HIFs), as well as expression of angiogenic factors such as VEGF stimulating pathological NV at the border between avascular and vascular zones, with maximum levels of pathological neovessels observable at P17 (Fig. 1A).27 At P17, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Eyes were immediately enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by dissection of the retinas. Dissected retinas were stained overnight with fluoresceinated Griffonia simplicifolia type 1 Isolectin B4 (Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated, 1:100 dilution, cat. no. 121413; Invitrogen [now Life Technologies], Grand Island, NY, USA) in 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS at room temperature. After washing with PBS three times, for 15 minutes each, retinas were whole-mounted onto microscope slides (Superfrost/Plus, 12-550-15; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with photoreceptor side down and embedded in antifade reagent (SlowFade, S2828; Invitrogen). Mosaic images covering the whole-mounted retinas were taken at ×5 magnification with a fluorescence microscope (AxioObserver Z1 microscope; Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany) and generated with image merging software (AxioVision 4.6.3.0; Carl Zeiss Microscopy) to produce a whole image of the retina.

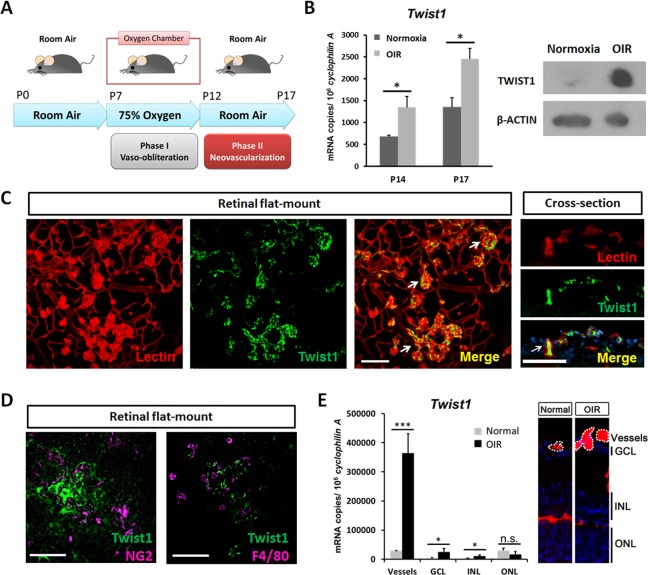

Figure 1.

Enrichment of TWIST1 in pathological retinal neovascularization in retinopathy. (A) Pathological neovascularization (NV) was induced in a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) by exposing neonatal mice and their nursing mothers to 75% ± 3% oxygen from postnatal day (P)7 to P12 (phase I, vaso-obliteration) and returning them to room air from P12 to P17 (phase II, vasoproliferation). (B) Twist1 mRNA expression was measured by RT-qPCR in OIR retinas at P14 and P17 compared with age-matched room air control mice (*P ≤ 0.05). Protein levels of TWIST1 in OIR retinas were evaluated at P17 compared with normoxic control using Western blot. (C) TWIST1 localizes specifically in pathological neovessels in OIR, with immunohistochemical staining showing colocalization of TWIST1 antibody (green) and Isolectin B4 (red, blood vessel marker) in retinal flat mounts (left) and in retinal cross sections showing areas surrounding the ganglion cell layer (right). Arrows indicate areas of colocalization (scale bar: 100 μm). (D) TWIST1 antibody staining (green) does not colocalize with pericyte marker NG2 (magenta) or macrophage marker F4/80 (magenta) in retinal flat mounts (scale bar: 100 μm). (E) Twist1 mRNA expression was analyzed in laser capture microdissected (LCM) pathological NV tufts and neural layers (RGC, INL, and ONL) from unfixed OIR retinas compared with normal vessels and corresponding neural layers isolated from normoxic retinas at P17, using RT-qPCR (***P ≤ 0.001; *P ≤ 0.05; n.s., not significant). Images on the right show representative retinal cross sections from normoxia and OIR retinas stained with Isolectin B4 (red) and DAPI (blue), with dotted lines highlighting microdissected normal vessels and pathological neovessel tufts. GCL, ganglion cell layer, INL, inner nuclear layer, ONL, outer nuclear layer.

Generation of Twist1 Conditional Knockout Mice and Tie2 Reporter Mice

Tie2-specific conditional Twist1 knockout mice (Tie2-Twist1cKO) and littermate control mice (Twist1flox/flox) were generated by crossing Tie2-Cre-expressing C57BL/6 mice with Twist1flox/flox mice (Fig. 2A).8 Tie2-Cre reporter mice were generated by crossing Tie2-Cre mice with ROSA mT/mG reporter mice.

Figure 2.

Conditional depletion of Twist1 in Tie2-expressing cells suppresses pathological neovessel formation in OIR. (A) Schematic illustration shows generation of Tie2-specific conditional Twist1 knockout mice (Tie2-Twist1cko) created by crossing Tie2-Cre mice with Twist1flox/flox mice exhibiting disruption in the Twist1 gene in Tie2-expressing cell with active Cre recombinase, which deletes floxed Twist1 gene. (B) Retinal vasculature of Tie2-Cre reporter mice crossed with Rosa mT/mG reporter strain, which universally expresses a red-fluorescent protein (mT). When crossed with Tie2-Cre mice, mT (red) is removed in Tie2-expressing cells with Cre recombinase expression, converting to a green fluorescent protein (mGFP), visible in blood vessels, confirming the expression of Tie-2-driven Cre recombinase in retinal vessels (scale bar: 200 μm). (C) RT-qPCR confirms that Twist1 expression was significantly depleted in OIR retinas of Tie2-Twist1cko mice compared with Twist1flox/flox littermate controls at P17 (*P ≤ 0.05). (D) Retinal blood vessel development in Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and Twist1flox/flox littermate controls was analyzed at P5 and P7. Representative P7 retinal images with Isolectin B4 staining (red) are shown for visualization of retinal vasculature (highlighted with yellow dashed line) normalized against total retinal area (white dashed line) (n = 5–11/group at P5, P = 0.59 and n = 8–15/group, P = 0.56, scale bar: 1000 μm). (E) Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate Twist1flox/flox control mice were exposed to OIR to induce retinopathy followed by retinal dissection and staining with Isolectin B4 (red). Tie2-Twist1cKO retinas show significant suppression of pathological neovessels compared with Twist1flox/flox controls at P17 in OIR (n = 10–12/group, scale bar: 1000 μm, **P ≤ 0.01). There is no significant difference in vaso-obliteration between the two groups at P17 (n = 10–12/group, P = 0.236; n.s., not significant).

Quantification of Retinal Vessel Loss and Neovascularization

Quantification of the retinal vasculature was carried out as previously described.29–31 Retinal vaso-obliteration and NV in OIR retinas were quantified using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) and ImageJ from National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html). The avascular area was visualized by absence of Isolectin B4 staining, which was manually outlined with Adobe Photoshop, and the number of pixels in the selected area was compared with the total number of pixels in the whole retina. The pathological neovascular tufts were recognized by their abnormal aggregated morphology from the normal finely branched vascular network. The number of pixels in abnormal neovascular areas was quantified using a previously established computer-aided SWIFT_NV method and also normalized as percentage of the whole retina area.29 The percentages of vaso-obliteration and NV were compared between Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate control Twist1flox/flox mice. Evaluation was done blindly with respect to the identity of the samples.

Laser-Induced CNV, Dissection, Staining, and Imaging

Choroidal neovascularization was induced by laser photocoagulation of Bruch's membrane with the Micron IV image-guided laser system (Phoenix Research Labs, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Briefly, 14- to 16-week-old Tie2-Twist1cKO and littermate Twist1flox/flox mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and pupils were dilated with Cyclomydril (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA). Laser photocoagulation (300 mW, 70 ms, with ~100-μm spot size) was performed with four laser burns in the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o'clock position of the posterior pole of the fundus at equal distance (2–3 disc diameters) from the optic nerve head. Seven days after laser photocoagulation, mice were anesthetized and euthanized by cervical dislocation, with eyes immediately enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by dissection of the posterior eye cups consisting of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)/choroid/sclera. To visualize the induced CNV, dissected RPE/choroid/sclera was treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 PBS for 1 hour at room temperature before labeling of choroid NV tufts overnight with Isolectin B4 in 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS at room temperature. After staining, the eye cups were washed three times, for 15 minutes each, followed by flat-mounting onto slides with sclera side down in mounting medium. Whole-mounted choroid images were taken at ×10 and ×20 magnification. Burns with bleeding were excluded, and only burns with bubble formation indicating breakage of Bruch's membrane were included in the study. Fused lesions and those lesions more than five times the mean lesion size in the same group were excluded according to established protocol.26 Both laser photocoagulation and CNV lesion quantification were performed in a masked fashion with the researchers blinded to the identity of samples. To collect laser-induced CNV membrane, posterior retinal area containing laser-induced CNV membrane/choroid complex was collected from mice at day 7 after laser photocoagulation. After dissection of posterior segment of eyeball with careful removal of retina and sclera, CNV membrane/choroid complex was collected in liquid nitrogen for RNA isolation.26

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was performed 6 days after laser photocoagulation. Mice were anesthetized and pupils were dilated as described above. Fluorescein AK-FLUOR (100 mg/mL, NDC 17478-101-12; Akorn, Lake Forest, IL, USA) was diluted to 10 mg/mL and injected intraperitoneally at 10 μL/g (body weight). Fluorescent fundus images were taken with a Micron IV retinal imaging system at 5 and 10 minutes after injection for observation of the posterior fundus area including the laser-induced CNV lesions. ImageJ was used by a masked observer to quantify the fluorescence intensity of CNV lesions. Briefly, the lesion areas were manually selected and measured using the “integrated intensity” function of ImageJ. The difference in integrated intensity between 5 and 10 minutes was recorded as an indicator of vascular leakage. In addition, fluorescein leakage was also graded by two independent masked observers using previously established criteria: 0 (not leaky), faint hyperfluorescence or mottled fluorescence without leakage; 1 (questionable leakage), hyperfluorescent lesion without progressive increase in size or intensity; 2a (leaky), hyperfluorescence increasing in intensity but not in size; 2b (pathologically significant leakage), hyperfluorescence increasing in both intensity and in size.32,33

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) of Retinal Vessels and Neuronal Layers

Eyes from P17 OIR or age-matched normoxic control mice were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound, sectioned at 10 μm, mounted on ribonuclease (RNase)-free polyethylene naphthalate glass slides (cat. no. 115005189; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). For LCM, frozen sections were dehydrated in 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol for 30 seconds each, washed with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water for 15 seconds, then stained with fluoresceinated Isolectin B4 with RNase inhibitor (cat. no. 03 335 399 001; Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at room temperature for 3 minutes. Leica LMD 6000 system (Leica Microsystems) was used to laser capture microdissect the pathological neovessel tufts from OIR retinas or normal vessels from normoxic control retinas. Retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner nuclear layer (INL), and outer nuclear layer (ONL) were also collected from OIR and normoxic retinas. Microdissected samples were directly collected into lysis buffer from the RNeasy micro kit (cat. no. 74004; Qiagen, Chatsworth, MD, USA).

Aortic Ring Sprouting Assay

Aortic ring sprouting assay was performed according to a previously reported protocol.34,35 Briefly, aortas from Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate control Twist1flox/flox mice were dissected on ice, cut into approximately 1-mm-long rings, and placed in growth factor-reduced Matrigel (cat. no. 354234; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) preseeded in 24-well tissue culture plates and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. After the Matrigel solidified, 500 μL complete medium (cat. no. 420-500; Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA, USA) with CultureBoost-R (cat. no. 4Z0-500-R; Cell Systems) was added to each well, and rings were cultured for 7 days (medium was changed every 3 days).34,36 Photomicrographs of individual explants were taken at 3, 4, 5, and 7 days after plating. Microvascular sprouting area was quantified by measuring the area covered by growing vessels with the SWIFT-Choroid/ImageJ computerized quantification method.34,35

Choroid Explant Sprouting Assay

Choroid sprouting assay was performed according to a previously reported protocol.34 Briefly, eyes were kept on ice after enucleated from Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate control Twist1flox/flox mice. After removal of the anterior segment, the choroid/sclera complex (also referred to as “choroid explant”) was separated from retina and cut into approximately 1- × 1-mm pieces. Choroid explants were seeded in growth factor-reduced Matrigel, cultured, and imaged with methods similar to those described above for aortic rings.

Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Culture

Human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) (cat. no. ACBRI 181; Cell Systems) were cultured in complete endothelial culture medium supplemented with CultureBoost-R and used from passage 4 to 7. Cells were transfected with TWIST1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (sense sequence: 5′-UUGAGGGUCUGAAUCUUGCUCAGCU-3′; antisense sequence: 5′-AGCUGAGCAAGAUUCAGACCCUCAA-3′; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) or negative control siRNA (cat. no. 1027281, 21 bp with sequence unavailable from vendor; Qiagen). The efficacy of siRNA knockdown was confirmed by RT–quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of cells collected 48 hours after transfection. Cell proliferation was assessed at 48 and 72 hours after transfection with TWIST1 siRNA or negative control siRNA using a MTT cell proliferation assay kit (cat. no. V13154; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) as described previously.36 Additional samples were collected after siRNA transfection for Western blot analysis.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Samples from cell culture, whole retinas, laser capture microdissected retinal vessels/layers, and choroid or laser-induced CNV membrane/choroid complex were lysed, homogenized with a mortar and pestle, and filtered through a biopolymer-shredding system (QiaShredder columns; Qiagen). Total RNA was then extracted using a RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Samples were treated with DNase (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) to ensure the removal of contaminating genome DNA and subsequently reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and a reverse transcriptase kit (cat. no. 18080-044; Invitrogen). Polymerase chain reaction primers for the housekeeping control genes (Cyclophilin A for murine samples and β-ACTIN for human cells) and target genes were designed using the Primer Bank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/) and NCBI Primer Blast database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Quantitative analysis of gene expression was done using a RT-qPCR sequence detection system (ABI Prism 7300, TaqMan; and SYBR Green master mix kit, cat. no. 4605; Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). Gene expression was calculated relative to expression of housekeeping control genes using the ΔCT method.28 The sequences of primers included: mouse primers, Twist1 forward 5′-GAGCAGAGACCAAATTCACAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GGGACACAAACGAGTGTTCA-3′; Vegfr2 forward 5′-TTTGGCAAATACAACCCTTCAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCAGAAGATACTGTCACCACC-3′; Cyclophilin A forward 5′-CAGACGCCACTGTCGCTTT-3′ and reverse 5′-TGTCTTTGGAACTTTGTCTGCAA-3′; human primers, TWIST1 forward 5′-GACAAGCTGAGCAAGATTCAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-TGAGCCACATAGCTGCAG-3′; VEGFR2 forward 5′-AGCGGGGCATGTACTGACGATTAT-3′ and reverse 5′-GGCGCACTCTTCCTCCAACTG-3′, β-ACTIN forward 5′-AGAGCTACGAGCTGCCTGAC-3′ and reverse 5′-AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG-3′.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot was performed as previously reported.22,37 Retinal or HRMEC samples were lysed in RIPA buffer (cat. no. 98035; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Pooled retinal lysates (15 μg) from three different animals were loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel (cat. no. NP00336BOX; Invitrogen) and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. For HRMECs, 15 μg protein was loaded into each well of SDS-PAGE gel. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C, followed by washing and incubation with secondary antibodies with horseradish peroxidase conjugation (Amersham [now GE Healthcare], Piscataway, NJ, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Chemiluminescence was generated by incubation with development solution (WP20005; Invitrogen) and captured on film. Density of immunoreactive bands was analyzed with ImageJ software. Primary antibodies included TWIST1 (cat. no. sc-15293; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), VEGFR2 (cat. no. 2479; Cell Signaling) and β-ACTIN (cat. no. A1978; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.); secondary antibodies included sheep anti-mouse IgG antibody (cat. no. NA931V; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and sheep anti-rabbit IgG antibody (cat. no. NA934V; GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Immunofluorescence Histochemistry

For whole-mount immunofluorescence histochemistry (IHC), mouse eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by retinal dissection, permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 PBS (TXPBS) for 1 hour, and 5 minutes of antigen retrieval treatment (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate in PBS) at room temperature. The whole-mounted retinas were blocked using an anti-mouse IgG solution (4.5% in PBS, M.O.M. Immunodetection Kit; Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 hour and then in 10% goat serum in TXPBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Retinas were then incubated with primary antibodies for TWIST1 (1:50 dilution, cat. no. ab50887; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and costained with Isolectin B4 and/or neural/glial antigen 2 (NG2) antibodies (1:100 dilution, cat. no. AB5320; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) or F4/80 antibodies (1:100 dilution, cat. no. ab6640; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the retinas were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature followed by imaging with confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems).

Statistics

Results are presented as mean ± SEM for both in vivo and in vitro studies. For all statistical analysis, two-sample Student's t-test was performed with P value ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant (n = number of eyes analyzed).

Results

Enrichment of TWIST1 in Pathological Retinal Neovascular Proliferation in Retinopathy

Using a well-established OIR model, we found that Twist1 mRNA expression was significantly upregulated during the vasoproliferative phase of OIR at P14 and P17 compared with age-matched room air control mice (P ≤ 0.05). TWIST1 protein levels in OIR retina were also increased at P17 compared with age-matched normoxic control using Western blot (Fig. 1B).

Localization of TWIST1 showed strong and specific staining in pathological neovessels using TWIST1 antibody costained with Isolectin B4 in flat mounts of P17 OIR retinas. There was minimal TWIST1 antibody staining in surrounding normal vessels (Fig. 1C). In cross sections of P17 OIR retinas, TWIST1 staining colocalized with nuclear counterstain DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) in cells with cell surface membrane stained positive for Isolectin B4, consistent with the known role of TWIST1 as a nuclear transcription factor (Fig. 1C). Moreover, TWIST1 antibody staining colocalized with neither pericyte marker NG2 nor macrophage marker F4/80 (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that expression of TWIST1 is highly enriched in pathological neovessels but barely detectable in normal quiescent vessels, blood vessel–associated pericytes, or macrophages.

Enrichment of TWIST1 in pathological neovessels was also quantitatively confirmed in neovessels isolated from OIR retinas. Laser capture microdissection was used to isolate pathological neovascular tufts from OIR retinas at P17 and normal vessels from age-matched normoxic control retinas. There was ~12-fold enrichment of Twist1 mRNA level in pathological neovessels from OIR compared with that in normoxic vessels. Modest levels of Twist1 were also observed in retinal neuronal layers, with higher levels in OIR than in normal neuronal layers (Fig. 1E). These data confirm that Twist1 is upregulated in pathological retinal neovessels and suggest that it may potentially contribute to pathological vessel proliferation in retinopathy.

Conditional Depletion of Twist1 in Tie2-Expressing Cells Suppresses Pathological Neovascularization in OIR

Since homozygous Twist1 null mutant embryos die around embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5) with vascular defects and delay of cranial neural tube closure,23,24 to further evaluate the role of OIR-induced Twist1 upregulation in retinal neovessels, we created Tie2-specific conditional Twist1 knockout mice (Tie2-Twist1cKO) by crossing Tie2-Cre mice with Twist1flox/flox mice exhibiting floxed disruption in the Twist1 gene.8,24 Expression of Tie2-driven Cre recombinase in retinal vessels was confirmed by crossing with floxed reporter mice (Rosa mT/mG), showing that retinal vessels display GFP (green fluorescence protein) as an indication of Cre expression, while other retinal cells not expressing Cre recombinase remain red (Fig. 2B). Substantial reduction of Twist1 mRNA expression in Tie2-Twist1cKO retinas was confirmed by RT-PCR compared with Twist1flox/flox littermate controls at P17 with OIR (P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 2C). Retinal blood vessel development was comparable between Tie2-Twist1cKO and Twist1flox/flox mice at both P5 and P7, with more than 80% of total retinal area vascularized in both groups at P7 (n = 5–11/group at P5, P = 0.59; n = 8–15/group at P7, P = 0.56, Fig. 2D). Importantly, Tie2-Twist1cKO mice subjected to OIR showed significantly decreased levels of pathological NV at P17 compared with Twist1flox/flox littermate controls (12.0% ± 0.37% of total retinal area in Tie2-Twist1cKO versus 14.83% ± 0.81% of total retinal area in Twist1flox/flox, n = 10–12/group, P ≤ 0.01, Fig. 2E). The vaso-obliterated retinal area did not differ significantly between Tie2-Twist1cKO and Twist1flox/flox mice at P17 (n = 10–12/group, P = 0.236, Fig. 2E). These data suggest that conditional Twist1 knockout leads to significantly decreased levels of pathological NV in OIR.

Tie2-Driven Conditional Knockout of Twist1 Results in Suppression of Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization

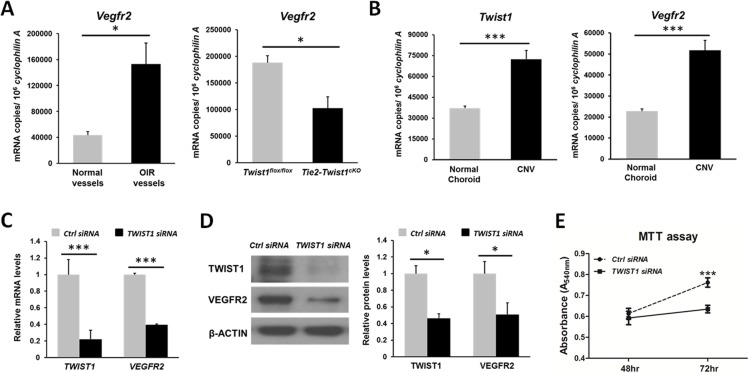

In order to determine whether TWIST1 also regulates pathological CNV, we treated adult Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate Twist1flox/flox controls with laser photocoagulation to induce CNV. Seven days after laser treatment, choroids were dissected and stained with Isolectin B4 to visualize CNV. Tie2-Twist1cKO mice showed significantly smaller CNV lesion size than that of littermate Twist1flox/flox controls (24,699 ± 3738 μm2 in Tie2-Twist1cKO versus 34,705 ± 3,704 μm2 in Twist1flox/flox; n = 20–26 eyes/group, P ≤ 0.05, Figs. 3A, 3B). In addition, at 6 days after laser photocoagulation, mice were subjected to FFA to evaluate levels of vascular leakage from CNV lesions. Images were taken at 5 and 10 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of fluorescein sodium. Vascular leakage measured by the difference in fluorescent intensity of exudated fluorescein sodium between 5 and 10 minutes showed 32.1% decreased levels in Tie2-Twist1cKO mice compared to Twist1flox/flox mice (P ≤ 0.05). Moreover, leakage grading showed that the percentage of lesions with significant pathologically leakage, defined as grade 2b lesion, was also much lower in Tie2-Twist1cKO mice compared with littermate Twist1flox/flox controls (31.2% of total lesions in Tie2-Twist1cKO versus 55.4% in Twist1flox/flox, n = 18–27 eyes/group, Figs. 3C, 3D).

Figure 3.

Tie2-driven conditional knockout of Twist1 results in suppression of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. (A) Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate Twist1flox/flox controls were subjected to laser photocoagulation to induce CNV. Seven days after treatment, choroids were dissected, stained with Isolectin B4 (red), and flat-mounted for imaging. (B) Quantification of CNV lesion sizes shows that Tie2-Twist1cKO lesions are significantly smaller compared with lesions from Twist1flox/flox littermate controls (n = 20–26 eyes/group, *P ≤ 0.05; ON, optic nerve head; scale bar: 100 μm). (C) CNV leakage in Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate floxed controls was imaged with fundus fluorescent angiography 6 days after laser treatment. Images were taken at 5 and 10 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of fluorescein sodium. (D) Quantification of fluorescent intensity of exudated fluorescein sodium and leakage grading show significantly decreased levels of vascular leakage in Tie2-Twist1cKO mice compared with littermate Twist1flox/flox control. Differences in fluorescent intensity of exudated fluorescein sodium between 5 and 10 minutes were quantified and normalized against that of the Twist1flox/flox littermate control as an indicator of vascular leakage. In addition, levels of leakage were evaluated by leakage grading according to established methods. Grade 0: not leaky; grade 1: questionable leakage; grade 2a: leaky; grade 2b: pathologically significant leakage (n = 18–27 eyes/group, *P ≤ 0.05, scale bars: 200 μm).

Loss of Twist1 Decreases Vascular Sprouting in Aortic Ring and Choroidal Explants

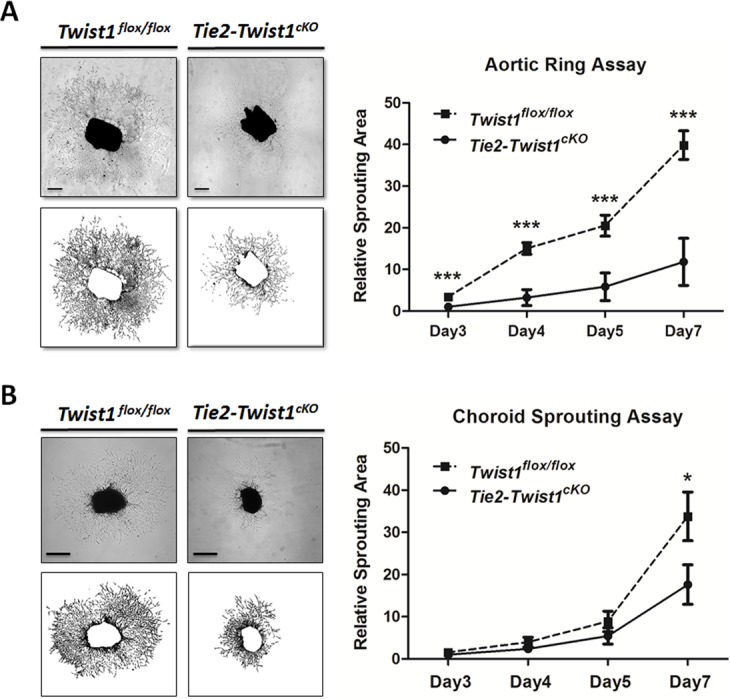

Having established that loss of Twist1 in Tie2-expressing cells suppresses pathological ocular NV in both OIR and laser-induced CNV models, we next evaluated the effects of conditional knockout of Twist1 on vascular sprouting using ex vivo aortic ring and choroid sprouting assays. Fragments of aorta and peripheral choroid were dissected from Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate Twist1flox/flox control mice and cultured according to previous published protocols.34–36,38 Starting from 3 days after explanting, the vascular sprouting areas in Tie2-Twist1cKO aortic rings were consistent and significantly less (~4-fold at day 7) than those of littermate Twist1flox/flox controls (n = 5–6/group, P ≤ 0.001, Fig. 4A). Similar effects were also observed in choroidal explants, with sprouting area in Tie2-Twist1cKO showing significant slower vascular growth compared with Twist1flox/flox controls at day 7 (n = 10–11/group, P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 4B).

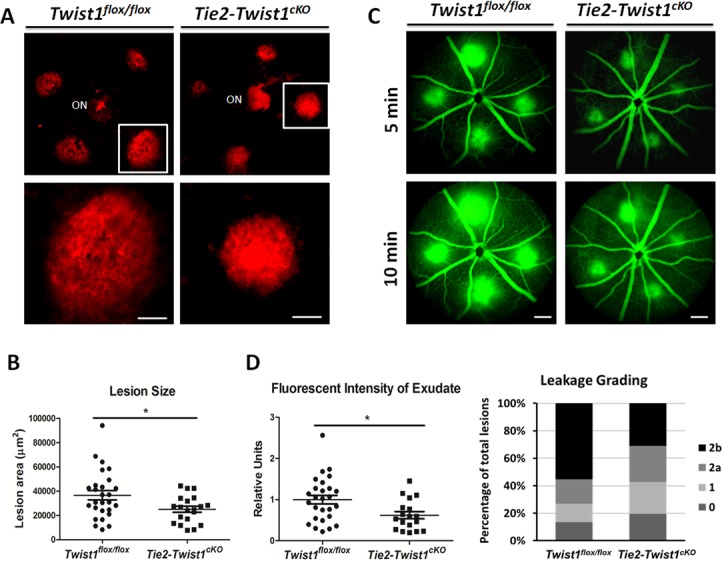

Figure 4.

Loss of Twist1 decreases vascular sprouting in aortic ring and choroid explants ex vivo. (A) Fragments of aorta were dissected from adult Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate Twist1flox/flox control mice and cultured as explants. Vascular sprouting areas were quantified, with aortic ring explants from Tie2-Twist1cKO mice showing significantly decreased sprouting areas compared with those of Twist1flox/flox littermate controls. Vascular sprouting areas are expressed as relative units normalized against the area of Tie2-Twist1cKO rings at day 3 (***P ≤ 0.001, n = 5–6/group, scale bar: 1 mm). (B) Peripheral choroid/sclera fragments were obtained from adult Tie2-Twist1cKO mice and littermate Twist1flox/flox control mice and cultured as explants. Vascular sprouting areas in choroid explants from Tie2-Twist1cKO mice show significantly decreased levels compared with those of Twist1flox/flox littermate controls at day 7 (*P ≤ 0.05, n = 10–11/group, scale bars: 500 μm).

Enrichment of Vegfr2 Levels in OIR Retina and Laser-Induced CNV Membrane Is Consistent With Increased Twist1 Levels

To further evaluate the role of TWIST1 in pathological angiogenesis, we evaluated in the OIR neovessels expression levels of a potential Twist1 target gene, Vegfr2, which is a critical receptor for angiogenic growth factor VEGF, and contains a potential TWIST1 binding site. Significantly higher levels of Vegfr2 mRNA were found in laser capture microdissected pathological NV tufts isolated from P17 OIR mice (~3-fold, P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 5A), consistent with increased levels of Twist1 in pathologic neovessels (Fig. 1E). Vegfr2 mRNA levels were also significantly suppressed in Tie2-Twist1cKO retinas compared with Twist1flox/flox controls (Fig. 5A), supporting a causal role of Twist1 in regulating Vegfr2 expression. In addition, both Twist1 and Vegfr2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in laser-induced CNV membrane compared with normal choroid without laser treatment (Fig. 5B), further supporting a role of Twist1 in promoting pathological choroidal angiogenesis.

Figure 5.

Enrichment of Vegfr2 in OIR retinas and laser CNV membrane; TWIST1 suppression with siRNA reduce VEGFR2 levels in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) and its proliferation. (A) Vegfr2 mRNA expression level is increased (~3-fold) significantly in laser capture microdissected (LCM) pathological NV tufts from OIR retinas compared with normal vessels isolated from normoxic retinas at P17. Vegfr2 mRNA level was also significantly suppressed (~50%) in Tie2-Twist1cKO retinas compared with Twist1flox/flox controls at P17, *P ≤ 0.05. (B) RT-qPCR analysis also revealed a consistent enrichment of Twist1 (~2-fold) and Vegfr2 (~2-fold) mRNA expression levels in laser-induced CNV membrane compared with that of choroid without laser photocoagulation (***P ≤ 0.001). (C) Confirmation of substantial inhibition of TWIST1 mRNA expression by TWIST1 siRNA treatment. HRMECs were transfected with TWIST1 siRNA or control negative siRNA, followed by RT-qPCR analysis. VEGFR2 mRNA expression was also significantly suppressed in HRMECs transfected with TWIST1 siRNA compared with that of control group (***P ≤ 0.001). (D) Protein levels of TWIST1 and VEGFR2 were significantly downregulated (~2-fold) in HRMECs treated by TWIST1 siRNA compared with those of negative control siRNA-treated HRMECs at 48 hours (*P ≤ 0.05). (E) HRMECs were transfected with TWIST1 siRNA or control negative siRNA. At 48 and 72 hours after siRNA transfection, cell proliferation was analyzed with MTT assay. Cell proliferation in the TWIST1 siRNA-treated group was significantly lower compared with that of the control siRNA-treated group at 72 hours. MTT assay results were expressed as spectrophotometric absorbance with a detection wavelength of 540 nm at 48 and 72 hours after siRNA transfection (n = 10–11, ***P ≤ 0.001).

TWIST1 Suppression With siRNA Decreases VEGFR2 Expression and Proliferation of Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells

Next we used siRNA to knock down TWIST1 in HRMEC culture. TWIST1 siRNA effectively suppressed expression of TWIST1 by ~78% compared with negative control siRNA, indicating successful inhibition of TWIST1 expression (Fig. 5C). Inhibition of TWIST1 by siRNA significantly suppressed VEGFR2 mRNA expression by ~60% (P ≤ 0.001, Fig. 5C). Protein levels of TWIST1 and VEGFR2 also showed significant decrease, with TWIST1 suppressed by ~54% and VEGFR2 by ~50% at 48 hours after TWIST1 siRNA treatment compared with control siRNA (P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 5D). In addition, at 48 and 72 hours after siRNA transfection, endothelial cell proliferation was analyzed with MTT assay. Proliferation of HRMECs was significantly decreased after transfection with TWIST1 siRNA for 72 hours, compared with control siRNA-treated HRMEC (P ≤ 0.001, Fig. 5E). These results suggest that the effect of TWIST1 on angiogenesis may be mediated in part through its modulation of VEGFR2 and endothelial cell proliferation.

Discussion

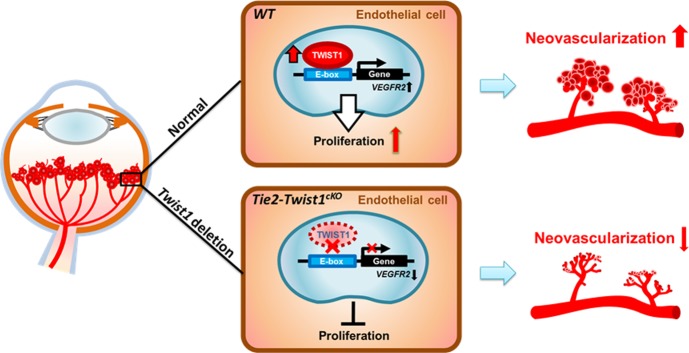

Pathological neovessel proliferation plays a critical role in many blinding vascular eye diseases.1,2,4 Elucidation of the underlying mechanisms of pathological neovessel formation is essential for developing potential therapeutic treatments to suppress NV in these sight-threatening diseases. TWIST1, a hypoxia-induced transcription factor,39 was reported to positively regulate tumor angiogenesis.14,17,19,40 Our previous work shows that TWIST1 is important for regulating pulmonary vessel permeability.8 In this present study, we investigated whether TWIST1 mediated neovascular proliferation in mouse models of pathologic ocular angiogenesis. Our results suggest that TWIST1 is a novel marker for pathological retinal neovessels, and that TWIST1 promotes pathological ocular NV, in part through modulating Vegfr2-dependent angiogenesis and endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the proposed role of TWIST1 in regulating pathological ocular angiogenesis. TWIST1 is specifically localized and upregulated in pathological neovascularization in retinopathy. TWIST1 modulates Vegfr2 expression in retinal vessel endothelial cells, potentially by recognizing a putative E-box region predicted in the promoter region of Vegfr2. TWIST1 promotes endothelial cell function and proliferation, leading to increased pathological neovascularization in vascular eye diseases. Conditional depletion of Twist1 in endothelial cells ameliorates pathological neovascularization in OIR and laser-induced CNV models.

In this study, we found that Twist1 mRNA was highly expressed in OIR at the hypoxia stage (P14 and P17), consistent with a previous report.41 The first phase of vessel loss in retinopathy results in retina ischemia, inducing tissue hypoxia in the second phase and thereby stabilization of the HIF-1α,42 which was reported to regulate Twist1 expression by binding directly to a hypoxia-response element in the proximal region of Twist1 promoter.39 Therefore upregulation of Twist1 in retinopathy is consistent with its suggested role as a HIF-responsive gene. Importantly, localization of TWIST1 protein shows strong specific enrichment in pathological retinal neovessels in OIR retina and minimal staining in surrounding normal quiescent retinal vessels or other cell types (pericytes, macrophages, or neurons). The enrichment of Twist1 in NV is confirmed quantitatively with laser capture microdissected retinal cellular layers showing that the highest level is found in pathological neovessels, suggesting that TWIST1 may represent a novel marker of pathologically proliferating vascular endothelial cells in the retina.

We found that conditional depletion of Twist1 in Tie2-expressing cells in OIR significantly suppressed pathological retinal neovessel formation, where endothelial cell proliferation plays an important role.43 Tie-2-driven Twist1 deficiency did not influence development retinal angiogenesis nor vaso-obliteration in OIR, suggesting that while TWIST1 is important for pathological vessel proliferation, Tie2-driven expression of Twist1 is potentially dispensable for normal retinal vessel development, and may not impact endothelial cell apoptosis during vessel loss. In an additional model of laser-induced CNV, we also observed significantly suppressed CNV in Tie2-Twist1cKO mice, further supporting a key role of TWIST1 in pathological ocular angiogenesis. These findings are in line with a proangiogenic role of TWIST1 in pathological conditions, as reported previously in tumor angiogenesis.19,21,22 Consistent with our previous report of TWIST1 regulating vascular integrity in the lung,8 in the CNV model, depletion of Twist1 also leads to decreased vascular leakage. This observation may reflect a potential effect of Twist1 on regulating Vegfr2 and Tie2 expression (Supplementary Fig. S1),8 both of which control cell–cell junctional integrity and leakage.

Our ex vivo angiogenesis assays—both aortic ring and choroid sprouting assays—indicate that loss of TWIST1 leads to decreased vascular sprouting from explants, confirming the proangiogenic role of TWIST1. These assays are widely used to analyze angiogenic roles of potential factors and to complement in vivo models of pathological angiogenesis.32,44 A potentially significant role of TWIST1 in choroid angiogenesis and CNV formation is also supported by higher expression levels of Twist1 in laser-induced CNV membrane compared with normal choroid. Additional retinal endothelial cell culture shows decreased endothelial cell proliferation when TWIST1 is knocked down with siRNA, further supporting a causal role of TWIST1 in mediating endothelial cell proliferation, which is an essential functional aspect of pathologic angiogenesis as observed in proliferative retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration.45,46 Together these data strongly support a vascular endothelial cell–specific role of TWIST1 in promoting endothelial cell function and proliferation, which may underlie the observed effects of TWIST1 in proliferating pathological angiogenesis in OIR and laser-induced CNV models.

While both OIR and laser-induced CNV models have inflammatory components,26 and inflammatory cells (including macrophages) contribute to both OIR and CNV formation,47–49 absence of TWIST1 staining in retinal macrophages in our study suggests a minimal role of inflammation in observed TWIST1 effects on ocular angiogenesis, although Tie2 is known to be expressed in both vascular endothelial cells and macrophages, and TWIST1 was reported to promote macrophage recruitment in tumor.22 In addition, our study found low levels of TWIST1 in retinal neurons, and as such, Tie2-driven Twist1 conditional knockout mice do not show complete depletion of Twist1 in the retinas, suggesting that neuronal TWIST1 may have additional unknown function in the retina.

At the molecular level, we found that TWIST1 regulates expression of Vegfr2, which may mediate in part the angiogenic effects of TWIST1 in retinopathy and CNV. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors are well known as crucial regulators of angiogenesis.50 Inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway suppresses not only tumor angiogenesis but also neovascular eye diseases characterized by abnormal retinal and choroid angiogenesis.42,51,52 Here we found that Vegfr2 mRNA levels were upregulated in pathological NV tufts in OIR retinas and in laser-induced CNV membrane, both enriched with Twist1 expression. Loss of Twist1 resulted in inhibition of Vegfr2 in the retinas, and TWIST1 suppression decreased VEGFR2 levels in HRMECs. This transcriptional regulation of VEGFR2 by TWIST1, as a known transcription factor, may potentially be achieved through binding of its HLH domain to a consensus E-box sequence as a known TWIST1 binding motif,53 which is predicted in the promoter region of VEGFR2. TWIST1 may thus modulate pathological angiogenesis in the eye at least in part through regulation of VEGFR2 expression and thereby the VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway (Fig. 6). These results of TWIST1-mediated VEGFR2 expression are consistent with our previous finding in mouse lungs8 and complement a previous report showing that TWIST1 increases secretion of VEGF in breast cancer,19 suggesting that TWIST1 may act in part through both the ligand and the receptors of the VEGF/VEGFR axis to influence angiogenesis in multiple pathological conditions. Suppression of TWIST1, however, does not show as strong inhibition of pathological NV in OIR as VEGFR2 inhibition,54 which may reflect partial regulation of VEGFR2 by TWIST1, as well as other unknown factors that are potentially altered in Twist1 knockout retinas, to compensate for the loss of Twist1 and downregulation of Vegfr2. In addition, consistent with our previous finding of Twist1 regulation of Tie2 in pulmonary vessels,8 increased Tie2 levels were found in Twist1-enriched pathologic OIR vessels, and decreased retinal levels of Tie2 were found in Twist1 conditional knockout retinas (Supplementary Fig. S1), further suggesting that additional factors other than VEGFR2 might be at work in mediating the effects of TWIST1 on pathologic ocular angiogenesis.

In addition to TWIST1, the TWIST subfamily of basic HLH proteins contains another highly conserved member, TWIST2, which shows some similarities but also roles separate from those of TWIST1 in mediating embryonic development and in disease.55 Twist2-driven VEGF expression regulates growth in neonatal mice,56 and Twist2-mediated expression of Sox17 or Wntless is required for pulmonary vascular development.57,58 While Twist2 was expressed in the OIR retinas at much lower levels than Twist1 (Supplementary Fig. S2), whether Twist2 plays a significant role in pathologic ocular angiogenesis is unclear and awaits further studies.

In summary, our study provides direct evidence for a novel role of transcription factor TWIST1 as a new regulator of pathologic ocular angiogenesis. Specific upregulation of TWIST1 in pathologic neovessels may act in part through the VEGF/VEGFR2 axis to promote endothelial cell function and proliferation, leading to increased pathological neovessels in proliferative eye diseases. The specific enrichment of TWIST1 in proliferating pathological neovessels suggests its potential as a direct drug target in designing therapeutic interventions that may offer the advantage of suppressing pathological neovessels without impacting normal retinal vessels.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lois E. H. Smith, MD, PhD, Andreas Stahl, MD, Meihua Ju, PhD, and Raffael Liegl, MD, for helpful discussion and/or critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dorothy T. Pei, BS, Hannah H. Bogardus, BS, and Ricky Z. Cui, BS, for excellent technical assistance. JL also thanks his advisor Junjun Zhang, MD, PhD (West China Hospital/West China School of Medicine), for mentoring and guidance.

Supported by NIH R01 EY024963, BrightFocus Foundation, Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund, a Boston Children's Hospital (BCH) Career Development Award, BCH Ophthalmology Foundation, and Alcon Research Institute (JC); the Joint PhD Program of the Chinese Scholarship Council (JL); American Heart Association, William Randolph Hearst Award, and American Brain Tumor Association (AM).

Disclosure: J. Li, None; C.-H. Liu, None; Y. Sun, None; Y. Gong, None; Z. Fu, None; L.P. Evans, None; K.T. Tian, None; A.M. Juan, None; C.G. Hurst, None; A. Mammoto, None; J. Chen, None

References

- 1. Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Muñoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122: 564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kempen JH, O'Colmain BJ, Leske MC, et al. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122: 552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sapieha P, Joyal JS, Rivera JC, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: understanding ischemic retinal vasculopathies at an extreme of life. J Clin Invest. 2010; 120: 3022–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen J, Smith LE. Retinopathy of prematurity. Angiogenesis. 2007; 10: 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dorrell M, Uusitalo-Jarvinen H, Aguilar E, Friedlander M. Ocular neovascularization: basic mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007; 52 (suppl 1): S3–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang S, Park JK, Duh EJ. Novel targets against retinal angiogenesis in diabetic retinopathy. Curr Diab Rep. 2012; 12: 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afzal A, Shaw LC, Ljubimov AV, Boulton ME, Segal MS, Grant MB. Retinal and choroidal microangiopathies: therapeutic opportunities. Microvasc Res. 2007; 74: 131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mammoto T, Jiang E, Jiang A, et al. Twist1 controls lung vascular permeability and endotoxin-induced pulmonary edema by altering tie2 expression. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e73407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simpson P. Maternal-zygotic gene interactions during formation of the dorsoventral pattern in Drosophila embryos. Genetics. 1983; 105: 615–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bourgeois P, Stoetzel C, Bolcato-Bellemin AL, Mattei MG, Perrin-Schmitt F. The human H-twist gene is located at 7p21 and encodes a B-HLH protein that is 96% similar to its murine M-twist counterpart. Mamm Genome. 1996; 7: 915–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howard TD, Paznekas WA, Green ED, et al. Mutations in TWIST, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997; 15: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reardon W, Winter RM. Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. J Med Genet. 1994; 31: 393–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. el Ghouzzi V, Le Merrer M, Perrin-Schmitt F, et al. Mutations of the TWIST gene in the Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997; 15: 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qin Q, Xu Y, He T, Qin C, Xu J. Normal and disease-related biological functions of Twist1 and underlying molecular mechanisms. Cell Res. 2012; 22: 90–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004; 117: 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li CW, Xia W, Huo L, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by TNF-alpha requires NF-kappaB-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Twist1. Cancer Res. 2012; 72: 1290–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khan MA, Chen HC, Zhang D, Fu J. Twist: a molecular target in cancer therapeutics. Tumour Biol. 2013; 34: 2497–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jan YN, Jan LY. HLH proteins, fly neurogenesis, and vertebrate myogenesis. Cell. 1993; 75: 827–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sossey-Alaoui K, Pluskota E, Davuluri G, et al. Kindlin-3 enhances breast cancer progression and metastasis by activating Twist-mediated angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2014; 28: 2260–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodrigues CO, Nerlick ST, White EL, Cleveland JL, King ML. A. Myc-Slug (Snail2)/Twist regulatory circuit directs vascular development. Development. 2008; 135: 1903–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu L, Roth JM, Brooks P, Ibrahim S, Karpatkin S. Twist is required for thrombin-induced tumor angiogenesis and growth. Cancer Res. 2008; 68: 4296–4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Low-Marchelli JM, Ardi VC, Vizcarra EA, van Rooijen N, Quigley JP, Yang J. Twist1 induces CCL2 and recruits macrophages to promote angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013; 73: 662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen ZF, Behringer RR. Twist is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995; 9: 686–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen YT, Akinwunmi PO, Deng JM, Tam OH, Behringer RR. Generation of a Twist1 conditional null allele in the mouse. Genesis. 2007; 45: 588–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, et al. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994; 35: 101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lambert V, Lecomte J, Hansen S, et al. Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model to study age-related macular degeneration in mice. Nat Protoc. 2013; 8: 2197–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, et al. The mouse retina as an angiogenesis model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 2813–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen J, Joyal JS, Hatton CJ, et al. Propranolol inhibition of beta-adrenergic receptor does not suppress pathologic neovascularization in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 2968–2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, et al. Computer-aided quantification of retinal neovascularization. Angiogenesis. 2009; 12: 297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Connor KM, Krah NM, Dennison RJ, et al. Quantification of oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse: a model of vessel loss, vessel regrowth and pathological angiogenesis. Nat Protoc. 2009; 4: 1565–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Banin E, Dorrell MI, Aguilar E, et al. T2-TrpRS inhibits preretinal neovascularization and enhances physiological vascular regrowth in OIR as assessed by a new method of quantification. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 2125–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu HG, Liu X, Kiss S, et al. Increased choroidal neovascularization following laser induction in mice lacking lysyl oxidase-like 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 2599–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marneros AG, She H, Zambarakji H, et al. Endogenous endostatin inhibits choroidal neovascularization. FASEB J. 2007; 21: 3809–3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shao Z, Friedlander M, Hurst CG, et al. Choroid sprouting assay: an ex vivo model of microvascular angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e69552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baker M, Robinson SD, Lechertier T, et al. Use of the mouse aortic ring assay to study angiogenesis. Nat Protoc. 2012; 7: 89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sapieha P, Stahl A, Chen J, et al. 5-Lipoxygenase metabolite 4-HDHA is a mediator of the antiangiogenic effect of {omega}-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Sci Transl Med. 2011; 3: 69ra12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gong Y, Yang X, He Q, et al. Sprouty4 regulates endothelial cell migration via modulating integrin beta3 stability through c-Src. Angiogenesis. 2013; 16: 861–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shao Z, Fu Z, Stahl A, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C8 omega3-long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites increase mouse retinal pathologic neovascularization--brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014; 34: 581–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang MH, Wu MZ, Chiou SH, et al. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1alpha promotes metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008; 10: 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mironchik Y, Winnard PT Jr, Vesuna F, et al. Twist overexpression induces in vivo angiogenesis and correlates with chromosomal instability in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005; 65: 10801–10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu T, Dong XG, Wang Y, Yan Y, Zhang JJ. The mechanism of twist gene regulation during the retina angiogenesis [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2008; 44: 634–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pierce EA, Avery RL, Foley ED, Aiello LP, Smith LE. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor expression in a mouse model of retinal neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92: 905–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ahn GO, Brown JM. Role of endothelial progenitors and other bone marrow-derived cells in the development of the tumor vasculature. Angiogenesis. 2009; 12: 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stahl A, Joyal JS, Chen J, et al. SOCS3 is an endogenous inhibitor of pathologic angiogenesis. Blood. 2012; 120: 2925–2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yang Y, Yang K, Li Y, et al. Decursin inhibited proliferation and angiogenesis of endothelial cells to suppress diabetic retinopathy via VEGFR2. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013; 378: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rusovici R, Patel CJ, Chalam KV. Bevacizumab inhibits proliferation of choroidal endothelial cells by regulation of the cell cycle. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013; 7: 321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Suner IJ, Hernandez EP, Monroy D, Csaky KG, Cousins SW. Macrophage depletion diminishes lesion size and severity in experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 3586–3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shi YY, Wang YS, Zhang ZX, et al. Monocyte/macrophages promote vasculogenesis in choroidal neovascularization in mice by stimulating SDF-1 expression in RPE cells. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011; 249: 1667–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ritter MR, Banin E, Moreno SK, Aguilar E, Dorrell MI, Friedlander M. Myeloid progenitors differentiate into microglia and promote vascular repair in a model of ischemic retinopathy. J Clin Invest. 2006; 116: 3266–3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999; 13: 9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology. 2005; 69 (suppl 3): 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aiello LP, Pierce EA, Foley ED, et al. Suppression of retinal neovascularization in vivo by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using soluble VEGF-receptor chimeric proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92: 10457–10461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barnes RM, Firulli AB. A twist of insight—the role of Twist-family bHLH factors in development. Int J Dev Biol. 2009; 53: 909–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu H, Zhang W, Xu Z, Caldwell RW, Caldwell RB, Brooks SE. Hyperoxia causes regression of vitreous neovascularization by downregulating VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 918–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Franco HL, Casasnovas J, Rodriguez-Medina JR, Cadilla CL. Redundant or separate entities?—roles of Twist1 and Twist2 as molecular switches during gene transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39: 1177–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Matthews JA, Sala FG, Speer AL, Li Y, Warburton D, Grikscheit TC. Mesenchymal-specific inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) attenuates growth in neonatal mice. J Surg Res. 2012; 172: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lange AW, Haitchi HM, LeCras TD, et al. Sox17 is required for normal pulmonary vascular morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2014; 387: 109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cornett B, Snowball J, Varisco BM, Lang R, Whitsett J, Sinner D. Wntless is required for peripheral lung differentiation and pulmonary vascular development. Dev Biol. 2013; 379: 38–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]