Abstract

The characteristics of plant assemblages influence ecosystem processes such as biomass accumulation and modulate terrestrial responses to global change factors such as elevated atmospheric CO2 and N deposition, but covariation between species richness (S) and functional group richness (F) among assemblages obscures the specific role of each in these ecosystem responses. In a 4-year study of grassland species grown under ambient and elevated CO2 and N in Minnesota, we experimentally varied plant S and F to assess their independent effects. We show here that at all CO2 and N levels, biomass increased with S, even with F constant at 1 or 4 groups. Likewise, with S at 4, biomass increased as F varied continuously from 1 to 4. The S and F effects were not dependent upon specific species or functional groups or combinations and resulted from complementarity. Biomass increases in response to CO2 and N, moreover, varied with time but were generally larger with increasing S (with F constant) and with increasing F (with S constant). These results indicate that S and F independently influence biomass accumulation and its response to elevated CO2 and N.

Biodiversity can be decomposed into several components including the number of species [species richness (S)], the number of functional groups [functional group richness (F)], the identity and composition of species, and the relative abundance of species and functional groups. Of these, S, F, and the composition of each of these are considered to be important in generating biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning, because each represents a fraction of total functional (i.e., trait and physiological) diversity, but their relative roles remain uncertain (1). Widespread declines in biodiversity, both locally and globally, make this uncertainty a general problem for predicting Earth and ecosystem response to biodiversity loss, but it is especially problematic when attempting to predict responses to global change, such as elevated CO2 and N deposition (2–8). Given current scenarios of co-occurring changes in diversity, climate, and other global change factors (9), our understanding of single-factor responses may be inadequate to predict ecosystem response to global change (3) that is inherently multifactorial in its nature.

In the same way that there are many elements to global change, many aspects of biodiversity are changing. Biodiversity consists of taxonomic diversity, which encompasses all traits of species weighted by their evolutionary relationships, whereas functional diversity focuses on physiological, morphological, and ecological traits related to the functions being measured. If functional groups of species can be identified, it may allow species with similar functions to be grouped in predicting their response to global change. In grasslands, for example, legumes, nonleguminous forbs, C3 grasses, and C4 grasses represent important functional distinctions relevant to production (4, 5, 10–14). If species within functional groups differed insignificantly in their contributions to responses being measured, only changes in F would matter and changes in S (i.e., within groups) would be inconsequential. In other words, if functional groups capture all variation in functional trait diversity, S within groups should not matter. Conversely, if functional group differences are minor in comparison with the many other differences taxonomic diversity captures, then F should not matter.

Several experiments have shown significant effects of increasing biodiversity (linked increases in S and F) on biomass accumulation (15–17) and suggested that F or S and functional group composition (15, 17) or species composition (16) play the key roles in providing the effects of biodiversity. However, in these experiments the effects of S and F were confounded, because S and F were highly correlated in the experimental design and it was impossible to fully separate the effects of each (15–17). Hooper and Vitousek (18) tested the relative effects of the number of plant functional groups and their composition (the identity of the groups) on soil N and productivity and concluded that functional group identity explained much more variation than did F, but they did not manipulate S to determine what role it played.

Other studies have explicitly tested the effects of functional identity, composition, or species deletions on response to elevated CO2 (4, 5, 7, 11–14). Moreover, during BioCON, a long-term grassland project studying biodiversity, CO2, and N interactions (6, 14, 19), we found that biomass enhancement in response to elevated atmospheric CO2 and/or N deposition increased with plant diversity (6). However, understanding the relative roles of S vs. F in those responses could not be achieved by using the randomly selected species combinations in that experiment, because S (ranging from 1 to 16) and F (ranging from 1 to 4) varied in tandem across the treatment diversity gradient, and across all treatments S and F were highly correlated [correlation coefficient (r) = 0.86, P < 0.001]. These reports collectively suggest that S, F, and composition seem to play roles in influencing responses to CO2, but they do not separate effects due to S from effects due to F.

Because no experimental studies have directly separated the effects of S and F under a single set of conditions (20), let alone under varying global change scenarios, it would be timely to better evaluate the contributions of these different components of diversity to ecosystem response to global change. We do so here by determining the relative contributions of S and F to diversity effects and how these interact with other global change factors, using a series of linked experiments that are nested within the BioCON project but distinct from the random diversity experiment reported upon previously (6). Additionally, the relative contribution to diversity effects of “selection” vs. “complementarity” remains controversial (2, 17), so herein we assess the relative effects of each.

To address the issue of S vs. F contributions to diversity effects, we tested for S effects holding F constant and for F effects holding S constant, using three complementary factorial experiments (experiments I–III). In all three experiments, all levels of S and F were exposed to all combinations of ambient and elevated CO2 and N treatments. Hence, these experiments provide insights into the generality and relative contributions of S vs. F to overall diversity effects and their interaction with experimentally manipulated CO2 and N regimes.

Methods

These experiments used 359 plots (2 × 2 m) arranged in six circular 20-m-diameter rings, at the Cedar Creek Natural History Area in central Minnesota (6,14). In three elevated CO2 rings, a free-air CO2 enrichment system was used during each growing season to maintain the CO2 concentration at an average of 560 μmol·mol-1, a concentration likely to be reached this century. Three ambient CO2 rings were treated identically but without additional CO2. Half of the plots in each ring received N amendments (4 g·m-2·year-1) applied over three dates each year. Plots were established in 1997 on a cleared secondary successional grassland by planting 12 g·m-2 of seed divided equally among all species in each plot. A total of 16 species, four each from four functional groups, were used in the study (6, 14). The functional groups were chosen because they are the important groups in native and secondary grasslands in this area. The 16 species were all native or naturalized to the Cedar Creek Natural History Area. They include four C4 grasses (Andropogon gerardii, Bouteloua gracilis, Schizachyrium scoparium, and Sorghastrum nutans), four C3 grasses (Agropyron repens, Bromus inermis, Koeleria cristata, and Poa pratensis), four N-fixing legumes (Amorpha canescens, Lespedeza capitata, Lupinus perennis, and Petalostemum villosum) and four non-N-fixing herbaceous species (Achillea millefolium, Anemone cylindrica, Asclepias tuberosa, and Solidago rigida).

Each experiment consisted of a subset of the 359 plots. Experiment I compared plots (n = 176) containing only a single functional group, but with either one or all four species per group present. All groups, and all four species per group, were equally represented in the monoculture plots (n = 128, 8 per each of the 16 species), and all four groups were equally represented in the four-species plots (n = 48, 12 per functional group). These plots were in turn randomly divided into the four CO2 × N levels. The design was thus a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial of S, CO2, and N with 32 (S = 1) or 12 (S = 4) replicates of unique combinations of these three variables (Tables 4–13, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Because all functional groups were equally represented at both levels of S, the experiment can also be analyzed as a 2 × 4 × 2 × 2 factorial design of S, group identity, CO2, and N, with one-fourth the level of replication per unique treatment.

Experiment II used only plots (n = 125) planted with all four functional groups and was a 3 × 2 × 2 factorial of S, CO2, and N, with S varying from 4 (n = 21) to 9 (n = 56) to 16 (n = 48) species, with these almost equally divided among the four CO2 × N levels (Table 4). Experiment III was a 4 × 2 × 2 factorial of F, CO2, and N and compared only plots (n = 123) planted with four species, with F treatments of 1 (n = 48), 2 (n = 20), 3 (n = 34), or 4 (n = 21) functional groups present, again divided among the four CO2 × N levels (Table 4). This experiment also allowed contrasts of increasing F when any one functional group was absent from all plots. In experiments II and III, the identity of species and functional groups in a plot was chosen at random (when not circumscribed by the design), and the intent of randomization and replication was to average across the set of potential species (i.e., across identity and composition) within each S or F level. In essence, the design of these experiments is neutral to identity (species or composition). Note that some plots serve as replicates in more than one experiment, which is why the sum of the replicates (n = 424) is greater than the number of plots (n = 359). In 1998–2001, plots received one of the four combinations of CO2 (ambient or 560 μmol·mol-1) and N (unamended or 4 g·m-2·year-1 added) treatments (6, 14).

Twice each year, in June and August, above-ground and below-ground biomass was harvested from each plot (6, 14). Above-ground biomass in every plot was sorted to species at each harvest. Fine-root production was measured in every plot once per year by using in-growth root cores (21). We examined results for the entire 1998–2001 period and used a repeated-measures ANOVA (jmp statistical software version 5.0.1a; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to test for main effects and interactions, and whether these changed over time [contrasting both season (i.e., June vs. August) and year]. The repeated-measures procedure accounted for the nonindependence among multiple measures of plots over time by using the variance among plots nested within CO2, N, and diversity levels as a random effect, such that measures that covary across time (seasons and years) were not counted as fully independent. The F statistic for the main effects of N, S, or F used the nested effect of plot within CO2, N, and diversity treatments. The F statistic for year and season and for treatment × time effects used the residual error term. The F statistic for CO2 used the nested effect of ring within CO2. We also partitioned the relative contributions to the diversity effects of selection and complementarity using the Loreau–Hector equation (2), calculated for each harvest from above-ground biomass data sorted to species from each plot in every harvest.

Results

In experiment I, which included plots with F = 1 and either one or four species, above-ground, root, and total biomass were significantly affected by either main effects of or interactions involving S, CO2, N, and year (Tables 1, 2, 3 and Fig. 1). Plots with four species had on average 40% greater total biomass than those with one species (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 1 A), even with F = 1. Thus, functional group diversity was not a prerequisite for S to have significant treatment effects. Moreover, the S effect occurred in all four functional groups (Table 2), modestly in C4 grasses (11% increase) and dramatically in C3 grasses (30% increase) and in the legume (67% increase) and forb (80% increase) groups. When we evaluated this effect statistically using a model including functional group identity, both S (P < 0.0001) and the interaction between S and group identity (P = 0.019) were significant, indicating that increasing S within functional groups generally influences biomass in all groups, but that the degree of response varied significantly among groups.

Table 1. Variation in biomass components and fine root production in relation to S and F in experiments I–III.

| All species

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | F | S | Annual fine root production | Below-ground biomass | Above-ground biomass | Total biomass |

| I | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 195 ± 10 | 464 ± 26 | 193 ± 9 | 656 ± 29 | |

| 1 | 4 | 261 ± 17 | 662 ± 43 | 258 ± 14 | 920 ± 47 | |

| II | ||||||

| 4 | 4 | 379 ± 34 | 897 ± 38 | 280 ± 14 | 1,178 ± 38 | |

| 4 | 9 | 361 ± 29 | 953 ± 23 | 315 ± 9 | 1,268 ± 23 | |

| 4 | 16 | 369 ± 29 | 950 ± 25 | 354 ± 10 | 1,305 ± 25 | |

| III | ||||||

| 1 | 4 | 261 ± 22 | 662 ± 38 | 258 ± 14 | 920 ± 35 | |

| 2 | 4 | 278 ± 33 | 687 ± 59 | 294 ± 21 | 981 ± 55 | |

| 3 | 4 | 333 ± 26 | 871 ± 46 | 326 ± 16 | 1,197 ± 42 | |

| 4 | 4 | 384 ± 33 | 897 ± 58 | 280 ± 21 | 1,178 ± 53 | |

Biomass (mean ± 1 SE; average for two harvests in June and August of 1998–2001; below-ground biomass of 0–20 cm in depth) and fine-root production (mean ± 1 SE; average per year for each plot in 1998–2001; 0–20 cm in depth) in plots with various F (number of functional groups) or S (number of species) treatments, averaged across CO2 and N treatments, in experiments I–III. All values shown are in g·m-2. Summaries of ANOVA are provided in Table 3. Responses to CO2 and N and interactions with S and F are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 2. Variation in total biomass in relation to S, F, and functional group composition in experiments I and III.

| Experiment | F | S | C4 grasses | No C4 grasses | C3 grasses | No C3 grasses | Forbs | No Forbs | Legumes | No legumes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 728 ± 27 | 981 ± 37 | 538 ± 61 | 377 ± 31 | |||||

| 1 | 4 | 805 ± 42 | 1,279 ± 60 | 966 ± 99 | 630 ± 50 | |||||

| III | ||||||||||

| 1 | 4 | 958 ± 33 | 800 ± 30 | 904 ± 31 | 1,016 ± 37 | |||||

| 2 | 4 | 979 ± 53 | 873 ± 56 | 972 ± 54 | 1,126 ± 49 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 1,343 ± 46 | 988 ± 55 | 1,376 ± 52 | 1,188 ± 41 | |||||

| 4 | 4 |

Biomass (mean ± 1 SE; average for two harvests in June and August of 1998–2001) in plots with various F (number of functional groups), S (number of species), and functional group treatments, averaged across CO2 and N treatments, in experiments I and III. All values shown are in g·m-2.

Table 3. Summary of significant effects levels from repeated-measures ANOVA for total, root, and above-ground biomass for experiments I–III.

| Experiment I, S = 1 or 4

|

Experiment II, S = 4, 9, or 16

|

Experiment III, F = 1, 2, 3, or 4

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Total biomass | Root biomass | Above-ground biomass | Total biomass | Root biomass | Above-ground biomass | Total biomass | Root biomass | Above-ground biomass |

| S/F* | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.009 | ns | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.045 |

| CO2 | 0.037 | 0.046 | ns | 0.087 | 0.085 | ns | 0.077 | ns | 0.012 |

| N | 0.004 | 0.077 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Season | ns | ns | <0.0001 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.0008 |

| Year | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| S/F* × season | ns | ns | 0.001 | ns | ns | <0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| S/F* × year | 0.0006 | ns | <0.0001 | ns | ns | 0.076 | ns | ns | 0.01 |

| CO2 × year | ns | ns | ns | 0.006 | 0.004 | ns | ns | 0.03 | ns |

| N × season | ns | ns | 0.003 | ns | ns | 0.059 | ns | ns | ns |

| N × year | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.068 | 0.028 | <0.0001 | 0.028 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | ns |

| Season × year | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0066 | 0.047 | 0.076 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

| S/F* × CO2 × year | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.016 | ns | ns | 0.019 |

| CO2 × season × year | ns | ns | ns | 0.019 | 0.002 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| S/F* × CO2 × N × year | 0.028 | 0.031 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.098 | 0.069 | ns |

| S/F* × CO2 × N × season | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.05 | ns |

| S/F* × N × season × year | 0.046 | 0.059 | ns | 0.056 | 0.0069 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| S/F* × CO2 × N × season × year | ns | ns | 0.0589 | ns | ns | 0.0589 | ns | ns | ns |

| Full-model R2 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.32 |

The results shown were achieved with whole models in experiments I–III (P < 0.001). Only variables significant for at least one of the measures shown are included. Depending on tests of linearity of responses, in some cases, year, S, or F was treated as a continuous rather than a nominal factor. Full ANOVA outputs are provided in Tables 5–13. ns, Nonsignificant; Full-model R2, coefficient of determination for the overall model that includes all terms.

The values shown for experiments I and II reflect S as a factor (i.e., S × season), whereas the values shown for experiment III reflect F as a factor (i.e., F × season)

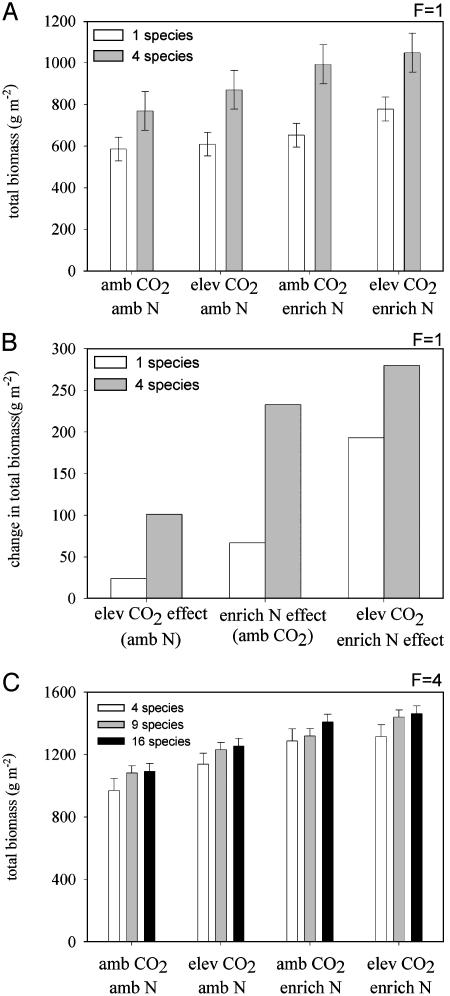

Fig. 1.

Effects of S at a standardized F on biomass and biomass responses to elevated CO2 and enriched N. (A) In experiment I, total biomass (above-ground plus below-ground, 0–20 cm in depth; +1 SE) for plots planted with one functional group (F = 1) and either one or four species, grown at four combinations of ambient (368 μmol·mol-1) and elevated (560 μmol·mol-1) concentrations of CO2 and ambient N and enriched N (4 g·m-2·year-1). Data were averaged over two harvests in each year from 1998 to 2001. (B) In experiment I, the change in total biomass (compared with ambient levels of both CO2 and N) in response to elevated CO2 alone (at ambient N), to enriched N alone (at ambient CO2), and to the combination of elevated CO2 and enriched N, pooled across years, for plots with F = 1 and S = 1 or 4. (C) In experiment II, total biomass (above-ground plus below-ground, 0–20 cm in depth; +1 SE) for plots planted with four functional groups (F = 4) and 4, 9, or 16 species, grown at four combinations of ambient (368 μmol·mol-1) and elevated (560 μmol·mol-1) concentrations of CO2 and ambient N and enriched N (4 g·m-2·year-1). Data were averaged over two harvests in each year from 1998 to 2001. amb, Ambient; elev, elevated; enrich, enriched.

We used the Loreau–Hector equation (2) to separate the diversity effects into complementarity and selection effects. When pooling across years, functional groups, and CO2 and N treatments, complementarity explained virtually 100% of the effects of S on biomass, indicating significant niche differentiation or facilitation (2) even among members of the same functional group. For all three experiments, the complementarity effect was always positive for all mixed species plots under all combinations of elevated CO2 and N and comparable in magnitude with the total diversity effect (data not shown). The selection effect ranged from negative to positive but on average was negative in all three experiments. Hence, diversity effects represent complementarity (2).

Moreover, responses to elevated CO2 or enriched N in experiment I were greater at higher S. Increases in biomass in response to elevated CO2, enriched N, or their combination were greater in four-species than in one-species plots (Fig. 1B), and these effects varied across years. For instance, the enhanced responsiveness of four-species vs. one-species plots to elevated CO2 or enriched N as individual factors grew larger over the years, whereas the magnitude of the enhanced responsiveness of four-species plots to the combination of elevated CO2 and enriched N declined with years (data not shown).

In experiment II, in which F = 4, increasing S from 4 to 9 to 16 also had significant positive effects on total and above-ground biomass (Tables 1 and 3 and Fig. 1C). The increase was incremental with increasing S and occurred at all combinations of CO2 and N. Above-ground biomass was 12% greater when S = 9 rather than S = 4 and an additional 12% greater when S = 16 rather than S = 9. Thus, even when F was saturated, increasing S still resulted in increased biomass. As for contrasts of S with F = 1, these effects of increasing S with F held constant at 4 were due to complementarity. Species number also influenced the changing responses over time to CO2 and N treatments (Table 3).

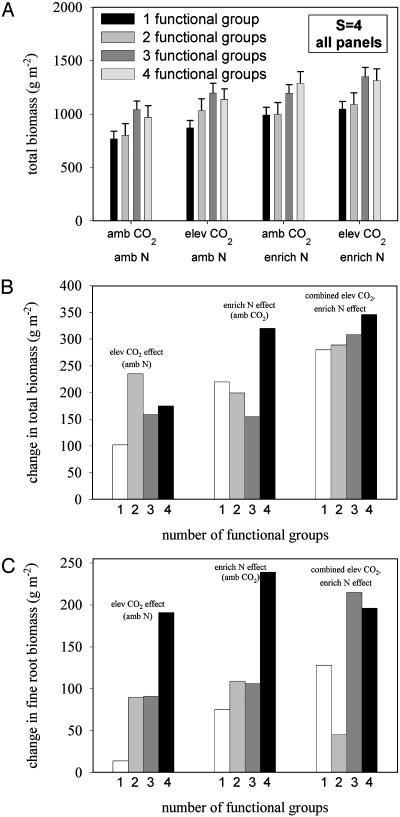

In experiment III, in which S = 4, biomass was significantly affected by F, CO2, N, and year (Tables 1, 2, 3 and Fig. 2), and the effects of CO2 and N over time were significantly influenced by F. Increasing F from one to three or four resulted in 28–30% greater total biomass on average, even with S constant at 4 (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 2). Total biomass responses to CO2 and N were also influenced by F (Fig. 2B) and largely manifest through effects on fine-root biomass (Fig. 2C), the largest component of total biomass. For instance, on average, when F = 1, elevated CO2 increased fine-root biomass by only 14 g·m-2 (2), but with F = 2, 3, and 4, elevated CO2 increased fine-root biomass by 90, 91, and 191 g·m-2 (2), respectively (Fig. 2C). Plots with high F also had greater biomass responses to enriched N alone and to the combination of elevated CO2 and enriched N (Fig. 2C). Thus, even when holding S constant at 4, plots with increasing F had greater biomass and had larger enhancements of biomass in response to CO2 and N, compared with plots with lower F. Based on the Loreau–Hector equation (2), these effects of increasing F were due almost entirely to complementarity.

Fig. 2.

Effects of F at a standardized S on biomass and biomass responses to elevated CO2 and enriched N. All data were from experiment III. (A) Total biomass (above-ground plus below-ground, 0–20 cm in depth; +1 SE) for plots planted with four species (S = 4) drawn from 1, 2, 3, or 4 functional groups, grown at four combinations of ambient (368 μmol·mol-1) and elevated (560 μmol·mol-1) concentrations of CO2 and ambient N and enriched N (4 g·m-2·year-1). Data were averaged over two harvests in each year from 1998 to 2001. (B) Change in total biomass (compared with ambient levels of both CO2 and N) in response to elevated CO2 alone (at ambient N), to enriched N alone (at ambient CO2), and to the combination of elevated CO2 and enriched N, in each year, for plots with S = 4 and F = 1, 2, 3, or 4. (C) Change in fine-root biomass (compared with ambient levels of both CO2 and N) in response to elevated CO2 alone (at ambient N), to enriched N alone (at ambient CO2), and to the combination of elevated CO2 and enriched N, in each year, for plots with S = 4 and F = 1, 2, 3, or 4. amb, Ambient; elev, elevated; enrich, enriched.

Contained within experiment III is a functional group omission experiment. In these contrasts, made for each group omitted in turn, all plots have four species from the three other functional groups, and F ranges from one to three. Analyzing in turn all of the three-way combinations of functional groups (i.e., with one group absent from each combination) and increasing F from 1 to 2 to 3 showed incrementally increased biomass (P < 0.01) in each case (Table 2). This result demonstrates that even with S held constant, the presence of no single functional group or pair was required in order for F to have positive effects on biomass, because in each case biomass increased with increasing F even when all plots were without one of the four groups.

Although above-ground biomass can be considered a surrogate for above-ground production, given annual turnover of shoots and leaves in the herbaceous species, below-ground biomass represents the combination of root production and longevity. However, responses to S and F of in-growth core root production measured in all plots across all 4 years generally agreed with responses of standing root biomass. For instance, in experiments I and III annual fine-root production increased (P < 0.001) with S or F, respectively, similar to the root biomass responses in these experiments (Tables 1 and 2), and in experiment II neither root production nor root standing crop was significantly related to S.

Discussion

Collectively, these results demonstrate that S and F act independently to influence biomass accumulation and its response to CO2 and N treatments, with resource partitioning and facilitation as mechanisms behind such impacts. Of the 16 species, 8 overyielded significantly (P < 0.05) in above-ground biomass in mixtures vs. monocultures in at least one harvest (data not shown), and 11 of the 16 species had positive effects on plot-level above-ground or below-ground biomass (23); hence, many species contribute to diversity effects (21–23). Moreover, these results suggest that effects of S and F on biomass and on biomass responses to CO2 and N appear to be general, because they were observed for a variety of compositional combinations. This outcome is likely because species within functional groups differ substantially in the temporal, spatial, and biological ways in which they acquire and use resources (1, 4, 19, 21–23). Moreover, functional groups also represent differences in innate biology (4, 5, 10–14, 19) sufficient that physiological diversity among these groups is also capable of positively impacting biomass accumulation in general and biomass responses to CO2 and N.

The results of experiments I–III were not due to only one or a few dominant species or compositional combinations. The effects of S (with F constant) occurred in every combination of species and at all levels of F from narrow (within every functional group alone) to broad (with all functional groups present) comparisons, and the so-called sampling or selection effect was never important. In a separate diversity experiment by Tilman et al. (15, 17) at this site, diversity effects were largely a result of F and heavily dependent on legume presence. Unlike in the Tilman experiment, in the BioCON study S effects were observed within each functional group (which was not testable previously), and the F effects occurred in all combinations, not just N-fixers and C4 grasses. Hence, the evidence from BioCON supports the idea of a broader and more general tendency for positive species interactions and niche differentiation across all kinds of species and functional group combinations.

All of these S and F effects held true in all combinations of CO2 and N, suggesting that their existence is general and independent of the limiting resource and that these 16 common grassland species have many axes of functional differentiation. Experiments I–III demonstrated that the increased biomass response to elevated CO2 and N of plots that are rich in both S and F (6) was due to significant independent interactive effects of both S (within functional groups) and F and was generated by positive species interactions.

Conclusions

The increase in biomass and its response to elevated CO2 and N of diverse communities likely arises from the increased system-level capacity to acquire, retain, and use resources of vegetation-containing mixtures (6, 15–18) of species varying in their ecophysiological and morphological characteristics important to resource processing (5, 13, 19, 21, 22). This increase in functional diversity with increasing S or F suggests that, for terrestrial ecosystems generally, declines in either S or F (independent of composition) could have important impacts on biomass accumulation in the face of myriad global change agents. Our results suggest that land managers should consider the potential impacts of different aspects of altered diversity, and global systems analysts should be alert to the possibility that predicting responses to multiple global change factors may be extremely difficult (3) if complex interactions, as seen in our studies, occur generally in nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Department of Energy Program for Ecological Research Grant DE-FG02-96ER62291, National Science Foundation Long-Term Ecological Research Program Grant DEB-0080382, and the University of Minnesota.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: S, species richness; F, functional group richness.

References

- 1.Schmid, B., Joshi, J. & Schlapfer, F. (2002) in The Functional Consequences of Biodiversity, eds. Kinzig, A., Pacala, S. & Tilman, D. (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton).

- 2.Loreau, M. & Hector, A. (2001) Nature 412, 72-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw, M. R., Zavaleta, E. S., Chiariello, N. R., Cleland, E. E., Mooney, H. A. & Field, C. B. (2002) Science 298, 1987-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebeisen, T., Luscher, A., Zanetti, S., Fischer, B. U., Hartwig, U. A., Frehner, M., Hendrey G. R., Blum, H. & Nosberger, J. (1997) Global Change Biol. 3, 149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wand, S. J., Midgley, G. F., Jones, M. H. & Curtis, P. S. (1999) Global Change Biol. 5, 723-741. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reich, P. B., Knops, J., Tilman, D., Craine, J., Ellsworth, D., Tjoelker, M., Lee, T., Naeem, S., Wedin, D., Bahauddin, D., et al. (2001) Nature 410, 809-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niklaus, P., Leadley, P., Schmid, B. & Körner, C. (2001) Ecol. Monogr. 71, 341-356. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naeem, S. (2002) Ecology 83, 2925-2935. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sala, O. E., Chapin, F. S., III, Armesto, J. J., Berlow, E., Bloomfield, J., Dirzo, R., Huber-Sanwald, E., Huenneke, L. F., Jackson, R. B., Kinzig, A., et al. (2000) Science 287, 1770-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owensby, C., Coyne, P., Ham, J., Auen, L. & Knapp, A. (1993) Ecol. Appl. 3, 644-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leadley, P. W., Niklaus, P. A., Stocker, R. & Körner, C. (1999) Oecologia 118, 39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedin, D. & Tilman, D. (1996) Science 274, 1720-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lüscher, A., Hendrey, G. R. & Nösberger, J. (1998) Oecologia 113, 37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reich, P. B., Tilman, D., Craine, J., Ellsworth, D., Tjoelker, M., Knops, J., Wedin, D., Naeem, S., Bahauddin, D., Goth, J., et al. (2001) New Phytol. 150, 435-448. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilman, D., Knops, J., Wedin, D., Reich, P. B., Ritchie, M. & Siemann, E. (1997) Science 277, 1300-1302. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hector, A., Schmid, B., Beierkuhnlein, C., Caldeira, M. C., Diemer, M., Dimitrakopoulos, P. G., Finn, J. A., Freitas, H., Giller, P. S., Good, J., et al. (1999) Science 286, 1123-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tilman, D., Reich, P., Knops, J., Wedin, D., Mielke, T. & Lehman, C. (2001) Science 294, 843-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper, D. & Vitousek, P. (1997) Science 277, 1302-1305. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, T. D., Tjoelker, M. G., Ellsworth, D. S. & Reich, P. B. (2001) New Phytol. 150, 405-418. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dìaz, S. & Cabido, M. (2001) Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 646-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craine, J., Tilman, D., Wedin, D., Reich, P., Tjoelker, M. & Knops, J. (2002) Funct. Ecol. 16, 563-574. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKane, R. B., Johnson, L. C., Shaver, G. R., Nadelhoffer, K. J., Rastetter, E. B., Fry, B., Giblin, A. E., Kielland, K., Kwiatkowski, B. L., Laundre, J. A., et al. (2002) Nature 415, 68-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craine, J. M., Reich, P. B., Tilman, G. D., Ellsworth, D., Fargione, J., Knops, J. & Naeem, S. (2003) Ecol. Lett. 6, 623-630. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.