Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the frequency of HRCT findings and their distribution in the lung parenchyma of patients with organizing pneumonia.

METHODS:

This was a retrospective review of the HRCT scans of 36 adult patients (26 females and 10 males) with biopsy-proven organizing pneumonia. The patients were between 19 and 82 years of age (mean age, 56.2 years). The HRCT images were evaluated by two independent observers, discordant interpretations being resolved by consensus.

RESULTS:

The most common HRCT finding was that of ground-glass opacities, which were seen in 88.9% of the cases. The second most common finding was consolidation (in 83.3% of cases), followed by peribronchovascular opacities (in 52.8%), reticulation (in 38.9%), bronchiectasis (in 33.3%), interstitial nodules (in 27.8%), interlobular septal thickening (in 27.8%), perilobular pattern (in 22.2%), the reversed halo sign (in 16.7%), airspace nodules (in 11.1%), and the halo sign (in 8.3%). The lesions were predominantly bilateral, the middle and lower lung fields being the areas most commonly affected.

CONCLUSIONS:

Ground-glass opacities and consolidation were the most common findings, with a predominantly random distribution, although they were more common in the middle and lower thirds of the lungs.

Keywords: Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; Respiratory tract diseases; Tomography, X-ray computed

Introduction

Organizing pneumonia (OP) is a clinical entity that is associated with nonspecific clinical findings, radiographic findings, and pulmonary function test results.( 1 ) It corresponds to a histological pattern characterized by granulation tissue polyps within alveolar ducts and alveoli, with chronic inflammation of the adjacent lung parenchyma. Similar lesions can also be observed in the respiratory bronchioles.( 2 , 3 ) The term cryptogenic OP (COP) is more appropriate than the term bronchiolitis obliterans OP, which has been abandoned.( 2 ) This is primarily due to the fact that the hallmark of COP is OP rather than bronchiolitis.( 4 )

When the cause is unknown, OP is classified as primary or cryptogenic; when a causal connection can be established, OP is classified as secondary. The causes of OP are numerous and include infections, iatrogenic causes (a reaction to drugs and radiation therapy), illicit drug use, and autoimmune diseases.( 1 , 2 , 5 , 6 ) The distinction between primary and secondary OP is extremely important because the treatment of patients with secondary OP includes treatment for OP itself and for the underlying disease or causative agent.( 1 ) The literature does not provide sufficient data to determine whether COP and secondary OP are two distinct entities or the same entity, in which there is nonspecific lung injury and repair.( 5 )

Although the diagnosis of OP is established by biopsy and histology, the clinical findings and imaging changes can suggest the diagnosis. In this context, HRCT is the imaging method of choice for diagnosing OP. In addition, HRCT allows us to evaluate the response to treatment and is useful for selecting the type of biopsy and the best site to perform it (when necessary). The objective of the present study was to determine the frequency of HRCT findings and their distribution in the lung parenchyma of patients with OP.

Methods

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Fluminense Federal University Antonio Pedro University Hospital, located in the city of Niterói, Brazil. Because this was a retrospective study examining existing clinical data and involving no changes in the treatment or follow-up of patients, no written informed consent was required. This was a retrospective descriptive observational study of the HRCT scans of 36 patients with histologically confirmed OP. Of those 36 patients, 20 had primary OP and 16 had secondary OP. The HRCT scans were randomly collected by personally contacting pulmonologists and radiologists and by searching the image databases of 8 medical institutions in 6 different Brazilian states in the 2005-2013 period. Of the 36 patients, 26 (72.2%) were female and 10 (27.8%) were male. The patients were between 19 and 82 years of age (mean age, 56.2 years).

Given that multiple institutions were involved, different CT scanners were used for image acquisition. All patients underwent HRCT scans, which were taken from the lung apices to the lung bases. Thin (1- or 2-mm) scans were taken during inhalation, in increments of 5 or 10 mm, with the patients in the supine position and without intravenous injection of iodinated contrast material, a high spatial resolution filter (bone filter) being used for image reconstruction. The images were obtained and reconstructed with a 512 × 512 pixel matrix and were photographed for evaluation of the lung fields with a window opening of 1,200-2,000 HU and an opening level of −300 to −700 HU. For mediastinal evaluation, a window opening of 350-500 HU and an opening level of 10-50 HU were used. The images were independently evaluated by two experienced observers. Discordant interpretations were resolved by consensus.

With regard to the HRCT findings, the following definitions were used:

ground-glass opacity-slightly increased attenuation of the lung parenchyma, unrelated to the obscuration of the vessels and adjacent airway walls

consolidation-increased attenuation of the lung parenchyma, resulting in obscuration of the vascular outlines and adjacent airway walls

peribronchovascular opacity-increased attenuation of the lung parenchyma adjacent to the peribronchovascular interstitium

reticulation-innumerable small linear opacities that, by summation, produce an appearance resembling a net

bronchiectasis-bronchial diameter greater than the diameter of the adjacent artery or absence of tapering of the bronchi and identification of a bronchus 1 cm from the pleural surface

interlobular septal thickening-thin linear opacities, which correspond to thickened interlobular septa

perilobular pattern-thick, irregular polygonal opacities in the periphery of the secondary pulmonary lobules

reversed halo sign-round, focal ground-glass opacity surrounded by a ring-shaped peripheral consolidation

airspace nodules-ill-defined nodules smaller than 1 cm and tending to confluence

halo sign-ground-glass opacity surrounding a nodule or mass

The criteria for the aforementioned findings are defined in the Fleischner Society Glossary of Terms,( 7 ) and the terms used are those found in the Brazilian Thoracic Association Department of Diagnostic Imaging consensus guidelines.( 8 , 9 ) The scans were also evaluated for the presence of pleural effusion, lymph node enlargement, and associated findings.

On the basis of their distribution in the lung parenchyma, the findings were classified as follows:

left-sided, right-sided, or bilateral findings

findings in the upper third, middle third, or lower third of the lungs

central or peripheral findings

In the craniocaudal axis, the lung was divided into upper third (from the lung apex to the level of the aortic arch), middle third (from the aortic arch to 2 cm below the carina), and lower third (from 2 cm below the carina to the costophrenic sulci). Lesions located predominantly in the middle third were defined as central lesions; those located predominantly in the upper and lower thirds were defined as peripheral lesions; and those with a predominantly random distribution were defined as random lesions.

Results

The most common HRCT findings (Table 1), in descending order, were as follows: ground-glass opacities (Figure 1); consolidation (Figure 2); peribronchovascular opacities (Figure 3); reticulation (Figure 4); bronchiectasis; interstitial nodules; interlobular septal thickening; perilobular pattern (Figure 5); reversed halo sign; airspace nodules; and halo sign. There were signs of architectural distortion in 14 (38.9%) of the 36 patients studied.

Table 1. Most common HRCT findings in 36 patients with organizing pneumonia.a.

| HRCT findings | Patients |

|---|---|

| Ground-glass opacities | 32 (88.9) |

| Consolidation | 30 (83.3) |

| Peribronchovascular opacities | 19 (52.8) |

| Reticulation | 14 (38.9) |

| Bronchiectasis | 12 (33.3) |

| Interstitial nodules | 10 (27.8) |

| Interlobular septal thickening | 10 (27.8) |

| Perilobular pattern | 8 (22.2) |

| Reversed halo sign | 6 (17.1) |

| Airspace nodules | 4 (11.1) |

| Halo sign | 3 (8.3) |

Values expressed as n (%).

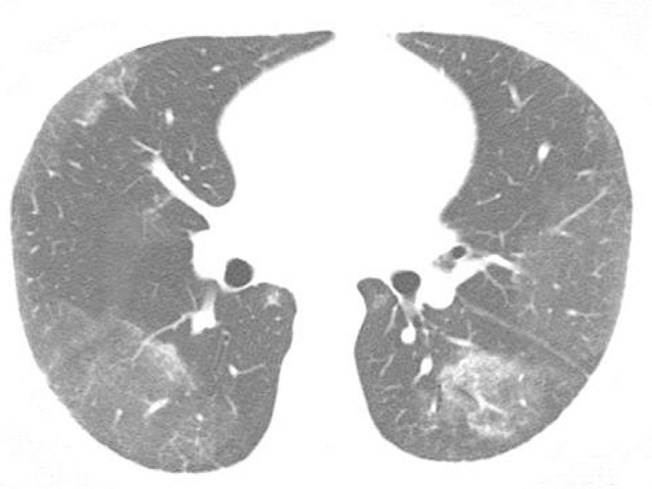

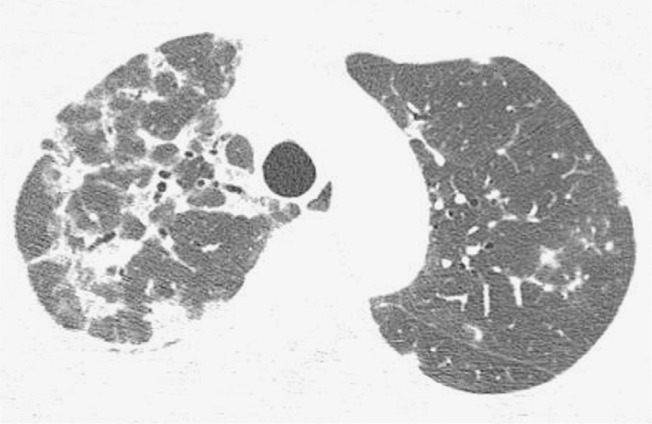

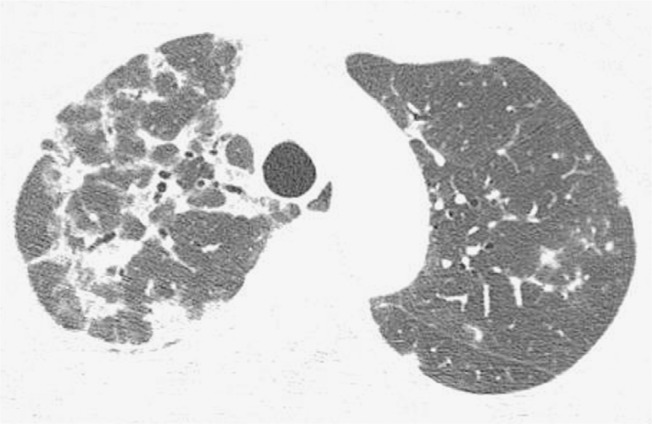

Figure 1. Chest HRCT scan (lung window) at the level of the middle lung field of a 39-year-old male patient, showing ground-glass opacities predominantly in the lung periphery.

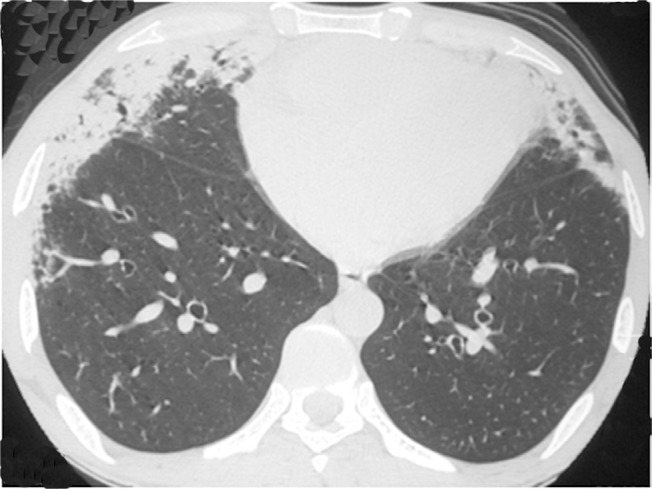

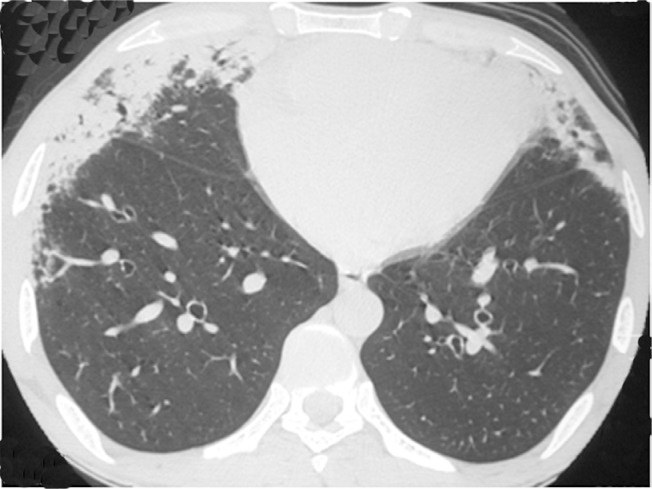

Figure 2. Chest HRCT scan at the level of the lower lung field of a 53-year-old male patient, showing areas of consolidation with air bronchograms and peripheral distribution in the anterior lung regions.

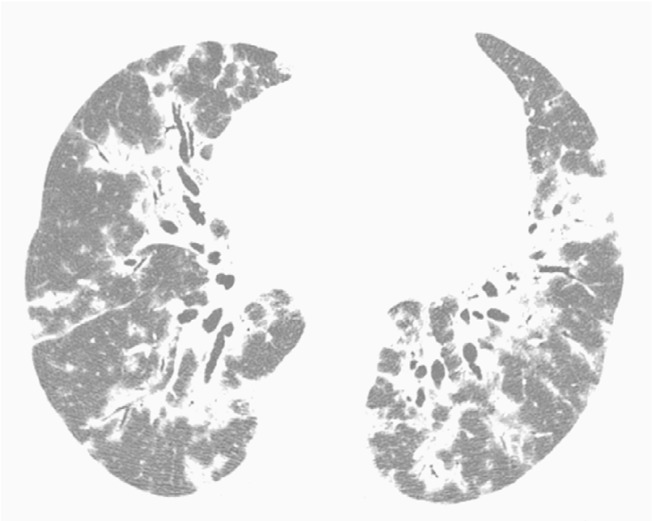

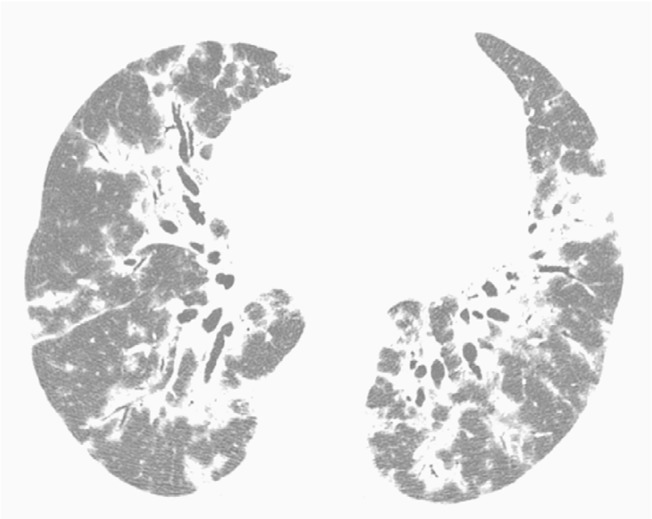

Figure 3. Chest HRCT scan (lung parenchymal window settings) of a 50-year-old male patient, showing bilateral consolidations with peribronchovascular distribution, interspersed with bronchiectasis.

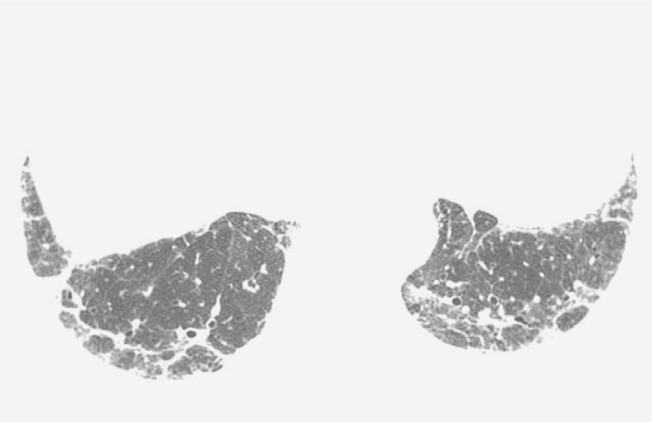

Figure 4. Chest HRCT scan (lung parenchymal window settings) at the level of the lung bases of a 75-year-old male patient, showing bilateral reticular opacities in the posterior lung regions.

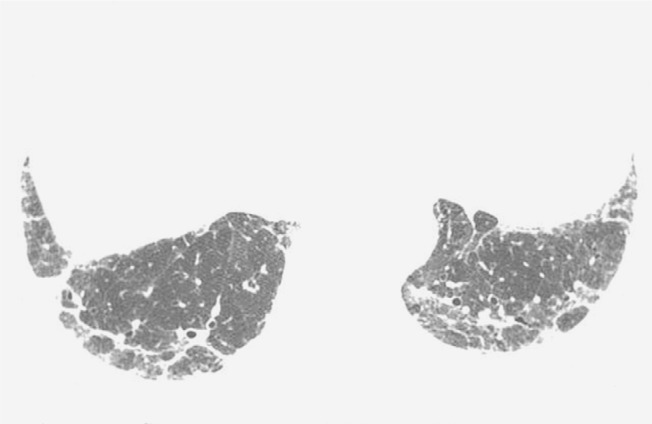

Figure 5. Chest HRCT scan (lung parenchymal window settings) at the level of the upper lobes of a 47-year-old female patient, showing a perilobular pattern predominantly on the right. Note faint nodular opacities in the left lung.

Of the 36 patients studied, 33 (91.7%) had bilateral lung involvement. In 2 (5.6%), only the right lung was affected, and, in 1 (2.8%), only the left lung was affected. With regard to the distribution of the lesions, the middle third of the lung was the most commonly affected area-in 33 (91.7%) of the 36 patients studied-followed by the lower third, in 28 (77.8%), and the upper third, in 21 (58.3%). In addition, the most common lesions were random lesions-in 26 (72.2%) of the 36 patients studied-followed by peripheral lesions, in 9 (25%), and central lesions, in 1 (2.8%).

Discussion

Studies evaluating the distribution of patients with COP and secondary OP by gender have shown no significant difference between the two groups.( 1 , 10 , 11 ) Of the 36 patients in the present study, 26 (72.2%) were female and 10 (27.8%) were male. With regard to age, studies have shown that OP is most common in the fifth and sixth decades of life.( 11 , 12 ) Although OP is rarely seen in children, there have been reports of OP in such individuals. In the present study, the patients were between 19 and 82 years of age (mean age, 56.2 years).

The initial symptoms of OP are nonspecific. Fever, cough, asthenia, mild dyspnea, anorexia, and weight loss are the most common findings, mimicking influenza.( 13 ) Therefore, an initial diagnosis of infectious disease is often made in patients with such findings. In addition, patients with such findings are often given empirical antibiotic therapy, which is ineffective. Fever can be absent in 50% of patients.( 2 ) Therefore, the diagnosis is often delayed, being generally suspected 4-10 weeks after the onset of symptoms. As the disease progresses, most of the initial symptoms can disappear, the exception being dyspnea, which sometimes worsens and becomes predominant. In some patients, the disease can progress rapidly, leading to severe dyspnea and even acute respiratory distress syndrome.( 14 ) In general, there is no difference between the clinical manifestations of COP and those of secondary OP.( 1 , 5 ) However, some clinical manifestations can provide important clues for the differential diagnosis. Severe arthralgia, myalgia, or both are more common in patients with OP associated with connective tissue disease.( 15 ) Patient history taking is essential, given that it can aid in identifying a cause for the OP. Patients with a history of lung radiation therapy can present with symptoms and imaging changes suggestive of OP in the lung parenchyma several months after treatment.( 16 )

In our sample, 20 patients (55.6%) had been diagnosed with primary (idiopathic) OP and 16 (44.4%) had been diagnosed with secondary OP on the basis of their clinical history and clinical examination findings. In studies involving larger samples of patients with OP, the proportion of patients with COP ranged from 52% to 65%,( 1 ,10 - 12) being similar to that found in the present study. Of the 16 patients with secondary OP in the present study, 5 (31.2%) had OP associated with drugs (amiodarone, in 2, nitrofurantoin, in 1, bleomycin, in 1, and busulfan, in 1), 3 (18.8%) had OP associated with infections (influenza A (H1N1) infection, in 2, and cryptococcosis, in 1), 3 (18.8%) had OP associated with bone marrow transplantation, 3 (18.8%) had OP associated with collagen diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, in 2, and systemic lupus erythematosus, in 1), and 2 (12.5%) had OP associated with malignancy (lymphoma, in 1, and colon cancer, in 1). The causes of secondary OP vary widely across studies and include drugs, infections, solid or hematologic malignancies and their treatments (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and bone marrow transplantation), and collagen diseases.( 1 , 10 - 12 )

The diagnosis of OP is made by biopsy and histology. However, clinical and physical examination findings (including an investigation of possible causes), together with imaging changes, can suggest the diagnosis.( 2 ) Histopathological examination reveals irregular filling of the alveoli, alveolar ducts, and respiratory bronchioles by granulation tissue plugs, which are known as Masson bodies.( 3 ) There is also a process of intra-alveolar fibrosis resulting from the organization of an inflammatory exudate. Unlike usual interstitial pneumonia, OP is not related to a progressive and irreversible fibrotic process.( 17 ) After a diagnosis of OP is established, it is necessary to determine the cause, which can be relatively evident or require further investigation.( 2 ) In our study, all cases of OP were histopathologically confirmed after transbronchial biopsy, in 17 (47.2%); CT-guided transthoracic biopsy, in 5 (13.9%); video-assisted thoracoscopic biopsy, in 8 (22.2%); and open lung biopsy, in 5 (13.9%). In 1 (2.8%), the diagnosis was confirmed by autopsy.

Although some authors have reported using surgical biopsies more frequently (in 88% of their patients),( 12 ) transbronchial biopsy was used in most of the studies involving large samples of patients with OP (being used in 67-78% of the patients). ( 1 , 10 ) Although surgical biopsy (via thoracoscopy or open thoracotomy) remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of OP, transbronchial biopsy can be conclusive in most cases if the findings are appropriately related to the clinical and CT findings.( 1 )

For evaluating OP, HRCT is the imaging method of choice. There are no differences between COP and secondary OP regarding HRCT findings. ( 1 ) However, Vasu et al.( 12 ) showed that pleural effusion was more common in patients with secondary OP than in those with COP.

The most common finding in patients with OP is that of consolidation and ground-glass opacities, which are usually bilateral and peripheral. ( 16 ) However, such opacities are nonspecific, being often mistaken for infectious pneumonia.( 18 , 19 ) In our sample, the most common findings were ground-glass opacities and consolidations, seen in 89% and 83%, respectively. Our findings are similar to those of larger studies.( 1 , 20 , 21 )

A solitary focal opacity is an uncommon presentation of OP that is known as focal OP and accounts for 10-15% of all cases.( 5 ) The diagnosis is usually made by biopsy of a nodule or mass that was removed because of a suspicion of bronchogenic carcinoma.( 7 ) In the present study, only 1 patient (2.8%) had focal OP. In that patient, the HRCT finding was a nodule with the halo sign.

It is known that OP can also present as overlapping interstitial and alveolar opacities. In addition, OP can overlap with other types of interstitial pneumonia, particularly idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.( 22 ) This pattern is characterized by a relative lack of consolidation and ground-glass opacities, with a predominance of reticular opacities with architectural distortion.( 23 ) In our sample, there were signs of architectural distortion in 14 patients (38.9%), a proportion that is higher than that reported in the literature (i.e., 10-18%).( 1 , 20 ) It should be noted that none of our patients had previously been treated for OP.

Although the reversed halo sign was initially considered to be an OP-specific finding,( 24 ) it was subsequently described in a number of other diseases.( 25 - 27 ) Nevertheless, it is an important clue to the diagnosis of OP.( 28 , 29 ) In our study, the reversed halo sign was seen in 6 patients (17.1%). In a study by Kim et al., the reversed halo sign was found in 19% of the cases.( 24 ) However, it was not found in other studies involving large samples of patients.( 1 , 12 , 20 , 21 ) It is known that OP can present as centrilobular nodules of 3-5 mm and small (1- to 10-mm) nodular opacities that are typically ill-defined. The differential diagnosis with metastases is crucial, especially in patients with a history of cancer, given that there is an association between OP and cancer. ( 30 ) In our study, airspace nodules were seen in 4 patients (11.1%).

Another important aspect in the HRCT evaluation of OP is the distribution of opacities. Subpleural/peribronchovascular distribution and a perilobular pattern can be found in approximately 60% of cases.( 20 , 21 , 31 ) In the present study, peribronchovascular opacities were found in 19 patients (52.8%). However, a perilobular pattern was found in only 8 patients (22.2%). Bilateral lung involvement predominated, being found in 33 (91.7%) of the 36 patients studied. Unilateral lung involvement was found in 3 patients, the right lung being affected in 2 (5.6%) and the left lung being affected in 1 (2.8%). With regard to the distribution of the HRCT findings, it was found to be random, peripheral, and central in 26 (72.2%), 9 (25%), and 1 (2.8%), respectively.

In the craniocaudal direction, the middle third of the lung was the most commonly affected area-in 33 (91.7%) of the 36 patients studied-followed by the lower third, in 28 (77.8%), and the upper third, in 21 (58.3%). Only one study involving a large sample of patients( 1 ) showed the aforementioned patterns of distribution, having shown a predominance of lesions in the lower lung fields in 55% of cases.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study. Second, it was a cross-sectional study, meaning that the progression and possible complications of OP were not evaluated. Third, the HRCT techniques varied according to the protocol used at each of the institutions involved in the study. Finally, the fact that the images were randomly collected from 8 institutions distributed in 6 Brazilian states made it difficult to collect clinical data to differentiate between COP and secondary OP. However, the aforementioned limitations did not negatively affect the analysis of the HRCT images. Despite its limitations, our study is one of the largest studies of HRCT scans of patients with histologically confirmed OP.

In summary, the most common HRCT finding was that of ground-glass opacities and consolidation, followed by reticulation, bronchiectasis, interstitial nodules, interlobular septal thickening, perilobular pattern, reversed halo sign, airspace nodules, and halo sign. The lesions were predominantly bilateral, the middle and lower thirds of the lungs being the most commonly affected areas.

Footnotes

Study carried out at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Financial support: None.

References

- 1.Drakopanagiotakis F, Paschalaki K, Abu-Hijleh M, Aswad B, Karagianidis N, Kastanakis E. Cryptogenic and secondary organizing pneumonia: clinical presentation, radiographic findings, treatment response, and prognosis. Chest. 2011;139(4):893–900. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(2):422–446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00013505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epler GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(2):158–164. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cottin V, Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33(5):462–475. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lohr RH, Boland BJ, Douglas WW, Dockrell DH, Colby TV, Swensen SJ. Organizing pneumonia. Features and prognosis of cryptogenic, secondary, and focal variants. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(12):1323–1329. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440330057006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Fontes CA, Santos ML, Valiante PM, Mano CM. Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia: high-resolution computed tomography-pathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80(3):e500–e504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brazilian Society Of Pulmonology and PhthisiologyDepartment of Diagnostic Imaging 2002-2004 Biennium Brazilian consensus on terminology used to describe computed tomography of the chest. J Bras Pneumol. 2005;31(2):149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva CI, Marchiori E, Souza AS, Júnior, Müller NL, Comissão de Imagem da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia Illustrated Brazilian consensus of terms and fundamental patterns in chest CT scans. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36(1):99–123. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132010000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sveinsson OA, Isaksson HJ, Sigvaldason A, Yngvason F, Aspelund T, Gudmundsson G. Clinical features in secondary and cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(6):689–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basarakodu KR, Aronow WS, Nair CK, Lakkireddy D, Kondur A, Korlakunta H. Differences in treatment and in outcomes between idiopathic and secondary forms of organizing pneumonia. Am J Ther. 2007;14(5):422–426. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000249905.63211.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasu TS, Cavallazzi R, Hirani A, Sharma D, Weibel SB, Kane GC. Clinical and radiologic distinctions between secondary bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Respir Care. 2009;54(8):1028–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epler GR, Colby TV, McLoud TC, Carrington CB, Gaensler EA. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(3):152–158. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nizami IY, Kissner DG, Visscher DW, Dubaybo BA. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. An acute and life-threatening syndrome. Chest. 1995;108(1):271–277. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henriet AC, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S, de Muret A, Favelle O, Crestani B. Organising pneumonia can be the inaugural manifestation in connective tissue diseases, including Sjogren's syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19(116):161–163. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein DM, Bennett MR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia with migratory pulmonary infiltrates. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158(3):515–517. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.3.1738986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colby TV, Myers JL. The clinical and histologic spectrum of bronchiolitis obliterans including bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Semin Respir Med. 1992;13:119–133. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordier JF, Loire R, Brune J. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Definition of characteristic clinical profiles in a series of 16 patients. Chest. 1989;96(5):999–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drakopanagiotakis F, Polychronopoulos V, Judson MA. Organizing pneumonia. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335(1):34–39. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31815d829d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JW, Lee KS, Lee HY, Chung MP, Yi CA, Kim TS. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: serial high-resolution CT findings in 22 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(4):916–922. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KS, Kullnig P, Hartman TE, Müller NL. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: CT findings in 43 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(3):543–546. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.3.8109493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katzenstein AL, Fiorelli RF. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis. Histologic features and clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(2):136–147. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199402000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oikonomou A, Hansell DM. Organizing pneumonia: the many morphological faces. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(6):1486–1496. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SJ, Lee KS, Ryu YH, Yoon YC, Choe KO, Kim TS. Reversed halo sign on high-resolution CT of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: diagnostic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(5):1251–1254. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchiori E, Melo SM, Vianna FG, Melo BS, Melo SS, Zanetti G. Pulmonary histoplasmosis presenting with the reversed halo sign on high-resolution CT scan. Chest. 2011;140(3):789–791. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Escuissato DL, Souza AS, Jr, Meirelles GS, Fagundes J. Reversed halo sign: high-resolution CT scan findings in 79 patients. Chest. 2012;141(5):1260–1266. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Meirelles GS, Escuissato DL, Souza AS, Jr, Hochhegger B. The reversed halo sign on high-resolution CT in infectious and noninfectious pulmonary diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(1):W69–W75. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchiori E, Marom EM, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, Irion KL, Godoy MC. Reversed halo sign in invasive fungal infections: criteria for differentiation from organizing pneumonia. Chest. 2012;142(6):1469–1473. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchiori E, Meirelles GS, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B. Optimizing the utility of high-resolution computed tomography in diagnosing cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Respir Med. 2011;105(2):322–323. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orseck MJ, Player KC, Woollen CD, Kelley H, White PF. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia mimicking multiple pulmonary metastases. Am Surg. 2000;66(1):11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ujita M, Renzoni EA, Veeraraghavan S, Wells AU, Hansell DM. Organizing pneumonia: perilobular pattern at thin-section CT. Radiology. 2004;232(3):757–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323031059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]