Abstract

Deregulation of myosin II-based contractility contributes to the pathogenesis of human diseases, such as cancer, which underscores the necessity for tight spatial and temporal control of myosin II activity. Recently, we demonstrated that activation of the mammalian α-kinase TRPM7 inhibits myosin II-based contractility in a Ca2+- and kinase-dependent manner. However, the molecular mechanism is poorly defined. Here, we demonstrate that TRPM7 phosphorylates the COOH-termini of both mouse and human myosin IIA heavy chains—the COOH-terminus being a region that is critical for filament stability. Phosphorylated residues were mapped to Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808. Mutation of these residues to alanine and that to aspartic acid lead to an increase and a decrease, respectively, in myosin IIA incorporation into the actomyosin cytoskeleton and accordingly affect subcellular localization. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that TRPM7 regulates myosin IIA filament stability and localization by phosphorylating a short stretch of amino acids within the α-helical tail of the myosin IIA heavy chain.

Keywords: actin, myosin IIA, cytoskeleton, phosphorylation, TRPM7

Introduction

The actomyosin cytoskeleton plays a vital role in maintaining the structural integrity of cells and in producing the force necessary to accomplish basic cellular functions, such as cytokinesis and migration.1–3 Myosins are a diverse superfamily of actin-based motor proteins that convert chemical energy into mechanical force.4 In muscle and nonmuscle cells, myosin II is the major motor protein driving cell contraction. Notably, the level of myosin II-based cytoskeletal tension generated inside the cell must be carefully controlled during cell behavior.5–7 Deregulation of pathways controlling myosin II activity contributes to the pathogenesis of several human diseases, including cancer.8

Myosin II is a hexameric protein composed of two heavy chains, two essential light chains and two regulatory light chains.9 To accomplish its cellular function, myosin II assembles into bipolar filaments through electrostatic interactions between the α-helical rod domain of its heavy chains.10 The motor domains on each end of a bipolar filament pull together oppositely oriented actin filaments to generate cortical tension. Three nonmuscle myosin II isoforms have been identified in mammalian cells; these are termed nonmuscle myosins IIA, IIB and IIC. These three isoforms have overlapping functions since defects due to the knockdown of a single nonmuscle myosin II isoform can be rescued by overexpressing the other isoforms.11 However, accumulating evidence suggests that the different myosin II isoforms also have nonredundant roles. Several studies have identified differences in mRNA expression, protein localization, enzymatic properties of the motor domain and binding partners between the three myosin II isoforms.12–20 Accordingly, mouse knockouts for nonmuscle myosins IIA and IIB show distinct phenotypes.21,22

In mammalian cells, phosphorylation of the regulatory light chains is the predominant mechanism regulating myosin II activity.3,23 Phosphorylation of the regulatory light chains stabilizes myosin II filaments, strengthens the actin–myosin association and activates the ATPase activity of the motor domain, leading to an increase in actomyosin contractility. However, strong experimental evidence exists for additional regulatory mechanisms, including myosin II heavy chain (MHCII) phosphorylation.24–27

Recently, we identified a novel signaling pathway downstream of the bradykinin receptor that regulates myosin II-based contractility in nonmuscle cells.28,29 Bradykinin stimulation of neuroblastoma cells activates TRPM7, promoting its association with myosin IIA in a Ca2+- and kinase-dependent manner, which leads to actomyosin relaxation and remodeling of cell adhesion structures. Since TRPM7 is related to Dictyostelium α-kinases,30 which control the assembly and localization of myosin II by phosphorylating its heavy chain,31,32 we proposed that TRPM7 may use a similar mechanism to inhibit myosin II-based contractility in mammalian cells. Indeed, we found that TRPM7 can phosphorylate associated myosin IIA.28 However, it is unclear if and how myosin IIA phosphorylation contributes to TRPM7-mediated cytoskeletal relaxation. Therefore, we investigated whether TRPM7 may affect actomyosin relaxation by directly phosphorylating MHCIIA to regulate filament stability.

Results

TRPM7 phosphorylates the region required for assembly of myosin IIA filaments

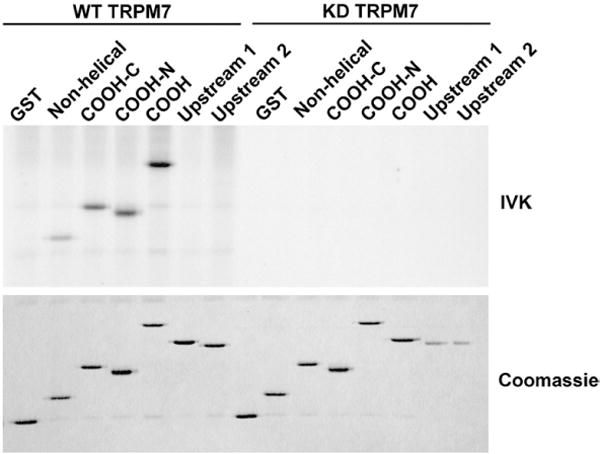

Previously, we demonstrated that TRPM7 phosphorylates the mouse MHCIIA.28 To assess the consequences of this phosphorylation event on myosin IIA function, we set out to map the residues phosphorylated by TRPM7 within the MHCIIA. The assembly of nonmuscle myosin II isoforms requires the extreme COOH-terminus, which is the only positively charged region.33,34 Therefore, this region is predicted to be highly affected by phosphorylation, a hypothesis supported by the fact that other regulatory proteins, including kinases, target this region.20,25 Therefore, we investigated whether TRPM7 could phosphorylate the extreme COOH-terminus of the coiled-coil domain of the MHCIIA. To this end, different regions of the mouse MHCIIA were expressed as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins (Fig. 1) and tested for their ability to be phosphorylated by TRPM7 in in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 2). Wild-type (WT) but not kinase-dead (KD) TRPM7 phosphorylated the COOH-terminus (amino acids 1795–1960) and different fragments derived from this region of mouse myosin IIA, including both helical and nonhelical components. In contrast, TRPM7 did not phosphorylate other fragments that were derived from areas located further towards the N-terminus of the MHCIIA. These results demonstrate that TRPM7 phosphorylates the positively charged COOH-terminus of the MHCIIA.

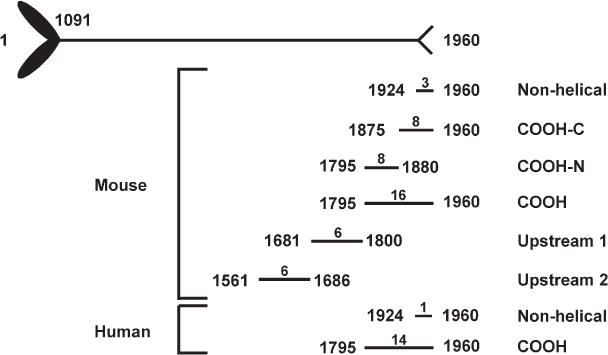

Fig. 1.

Fragments of the MHCIIA that served as substrate in TRPM7 kinase reactions. A schematic diagram of the MHCIIA is depicted, with the coiled-coil domain spanning amino acids 1091 to 1924. The MHCIIA ends with a short nonhelical tail piece (amino acids 1924–1960). For each myosin IIA fragment, the first and last amino acids are indicated on either side of the line. Above the line is the total number of threonine and serine residues within each fragment.

Fig. 2.

TRPM7 phosphorylates the COOH-terminus of mouse MHCIIA. Different regions of the coiled-coil domain of mouse MHCIIA were expressed as GST fusion proteins. The purified recombinant proteins were incubated with WT or KD TRPM7 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The products of the kinase reaction were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (bottom panel). Phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography (top panel).

TRPM7 phosphorylates mouse and human myosin IIA

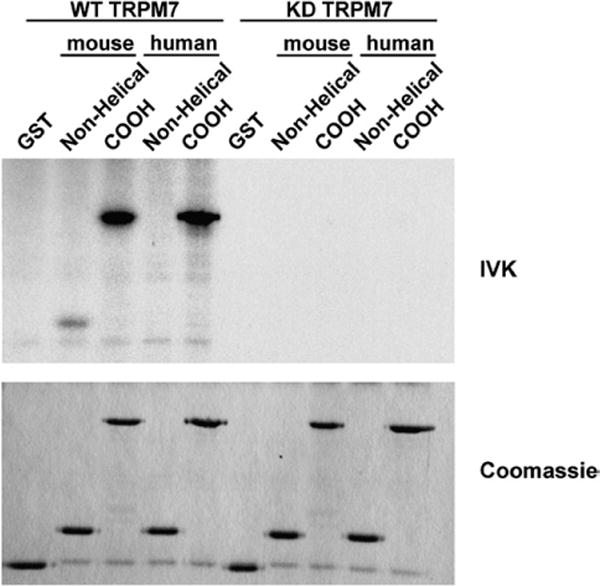

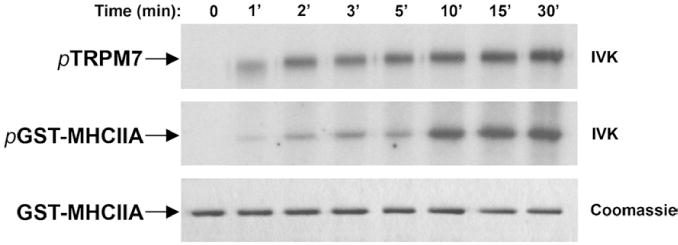

Certain kinases, such as calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, specifically phosphorylate the mouse MHCIIA but not the human MHCIIA.35 The differences appear to arise due to a lack of sequence conservation within the nonhelical tail. We therefore determined whether TRPM7 could also phosphorylate the COOH-terminus of human MHCIIA (Fig. 3). In vitro kinase assays showed that TRPM7 efficiently phosphorylates the COOH-termini of both mouse and human MHCIIA. Phosphorylation of MHCIIA was detectable within 1 min and increased progressively until it reached a maximum at about 10 min (Fig. 4). One notable difference was observed between mouse and human myosin IIA: While TRPM7 could phosphorylate the nonhelical tail of mouse MHCIIA, TRPM7 did not phosphorylate this region within the human homologue. Thus, our results show that TRPM7, in contrast to calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, phosphorylates the coiled-coil domain of both mouse and human MHCIIA.

Fig. 3.

TRPM7 phosphorylates the α-helical tail but not the nonhelical tail of human MHCIIA. The COOH-termini and nonhelical tails of mouse and human MHCIIA were purified as GST fusion proteins and incubated with WT or KD TRPM7 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining the gel with Coomassie brilliant blue (bottom panel). Phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography (top panel).

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of myosin IIA phosphorylation by TRPM7. Purified TRPM7 was mixed with 2 μg of GST–myosin IIA, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.1 mM ATP containing 5 μCi of [γ32P]ATP. The reaction proceeded at 30 °C for the indicated times, after which 20 mM EDTA was added to stop the kinase reaction. Proteins were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and detected by Coomassie staining (bottom panel). Phosphorylated TRPM7 and GST–myosin IIA were revealed by autoradiography (top and middle panels).

TRPM7 phosphorylates Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 in human myosin IIA

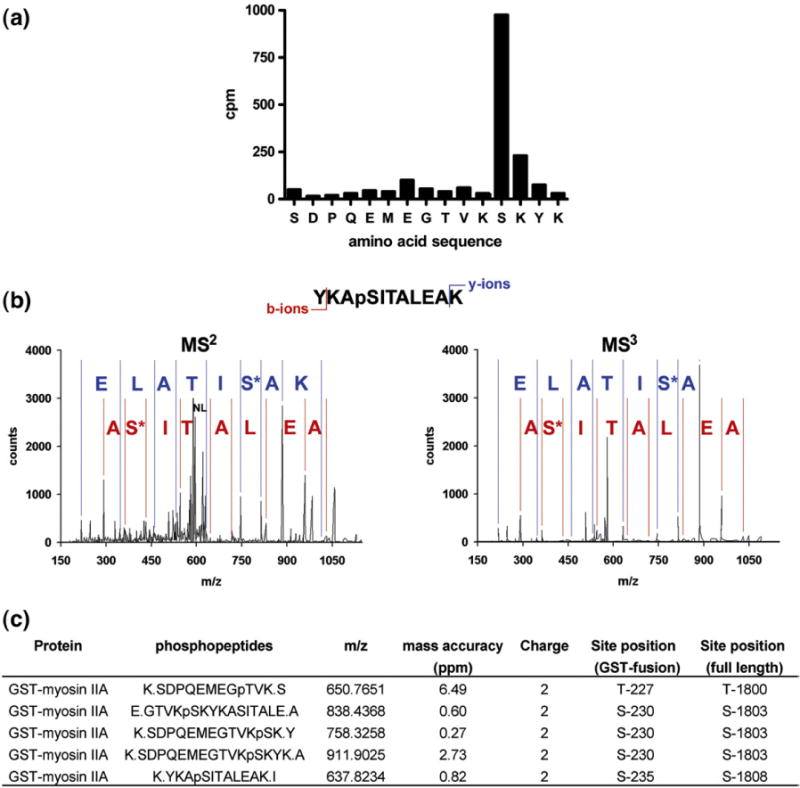

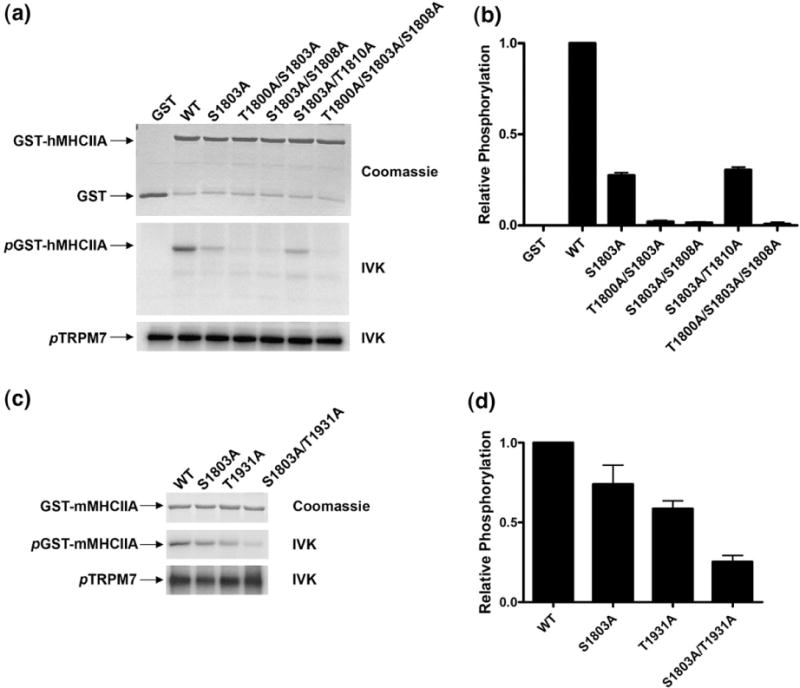

A multidisciplinary approach involving bioinformatics and proteomics was used to map the phosphorylation sites in the human MHCIIA. Recently, an algorithm was developed to predict residues phosphorylated by TRPM7 in its substrates (details of the algorithm will be published elsewhere; A. Ryazanov et al., unpublished results). This algorithm calculated that Ser1803 was the residue with the highest probability to be phosphorylated by TRPM7. The phosphorylation sites in the MHCIIA were mapped using two distinct approaches to further substantiate these predictions. Initially, 32P-labeled tryptic peptides from TRPM7-phosphorylated human MHCIIA were separated by reversed-phase HPLC. These peptides eluted off the column into three fractions at 33%, 43% and 54% v/v acetonitrile (data not shown). When peptides from the major peak (54%) were subjected to solid-phase sequencing, a burst of 32P release was observed after the 12th cycle of Edman degradation (Fig. 5a). The molecular mass of the peptide (1822.79) as determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI–TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) was identical with that expected for the tryptic phosphopeptide comprising the last three residues of GST fused to residues 1795–1806 of MHCIIA and phosphorylated at Ser1803. All the other fractions also contained peptides phosphorylated at Ser1803. However, mutation of Ser1803 to alanine reduced the incorporation of phosphate by only 70% compared with WT, suggesting the presence of additional phosphorylation sites within the MHCIIA (Fig. 6). We therefore further analyzed tryptic and GluC digests of phosphorylated MHCIIA by high-mass-accuracy MS using a linear ion trap quadrupole–Fourier transform (LTQ-FT) mass spectrometer. Several monophosphorylated peptides were detected using the LTQ-FT in nano-liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) by the loss of H3PO4 during MS/MS, and MS/MS spectral analysis of these peptides determined that, in addition to Ser1803, Thr1800 and Ser1808 are also phosphorylated by TRPM7 (Fig. 5b and c). Mutational analysis demonstrated that all three residues contribute to the overall phosphorylation of myosin IIA, with Ser1803 being the major phosphorylation site (Fig. 6a and b). The reduction in phosphorylation is not due to changes in MHCIIA structure since mutation of an irrelevant residue (Thr1810) had no effect on the efficiency of MHCIIA phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

Mapping of phosphorylation sites in MHCIIA. (a) Identification of Ser1803 by Edman degradation sequencing of 32P-labeled peptides. GST–MHCIIA COOH-terminus was incubated with TRPM7 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The phosphorylated GST–MHCIIA fusion protein was excised from the gel and digested with trypsin, and the peptide mixture was separated by HPLC on a C18 column. The phosphopeptides were sequenced by Edman sequencing, with 32P radioactivity being measured after each cycle of degradation. The phosphorylated residue was assigned by a combination of solid-phase Edman sequencing and MALDI–TOF. (b) Identification of phosphorylation sites by LC-MS/MS. Phosphorylated GST–MHCIIA COOH-terminus was digested with trypsin, and peptides were separated on a nano-LC C18 column, which was connected inline with a high-mass-accuracy LTQ-FT mass spectrometer. Representative MS2 and MS3 spectra of a peptide phosphorylated at position Ser1808 are depicted (m/z observed of parent ion=637.8227, mass accuracy=0.82 ppm, +2 charge state; NL indicates neutral loss of H3PO4, which triggers acquisition of MS3 spectrum). (c) Summary table of the phosphorylation site results by LC-MS/MS.

Fig. 6.

Ser1803 is the major phosphorylation site in the COOH-termini of the coiled-coil domains of both human and mouse myosin IIA. (a) Mutations of Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 in human MHCIIA reduce phosphorylation to background levels. The phosphorylated residues mapped in GST–human MHCIIA COOH were mutated to alanine individually or in combination. Since substrate recognition by α-kinases may be influenced by the secondary structure, Thr1810, which was not identified by MS or predicted to be phosphorylated, was also mutated as a negative control. GST–human MHCIIA proteins were incubated with TRPM7 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Equal loading of the GST fusion proteins was verified by Coomassie staining (top panel), and phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. The phosphorylation of the different GST–human MHCIIA proteins by TRPM7 is depicted in the middle panel. The presence of equal levels of kinase activity in each sample was determined by monitoring TRPM7 autophosphorylation (bottom panel). (b) Quantification of the degree of phosphorylation of the different GST–human MHCIIA fusion proteins by TRPM7 using phosphorimager analysis. The level of 32P incorporation into the WT GST–human MHCIIA fusion protein was set to 1, and phosphorylation of all other proteins is reported relative to this value. (c) Ser1803 is the major phosphorylation site in the helical region of mouse myosin IIA. GST–mouse MHCIIA was mutated at positions Ser1803 and Thr1931 either individually or in combination. Phosphorylation of these GST–mouse MHCIIA mutants by TRPM7 was compared with WT GST–mouse MHCIIA by in vitro kinase assay as described in (b). (d) Phosphorylation of different mouse MHCIIA proteins was quantified as described in (b).

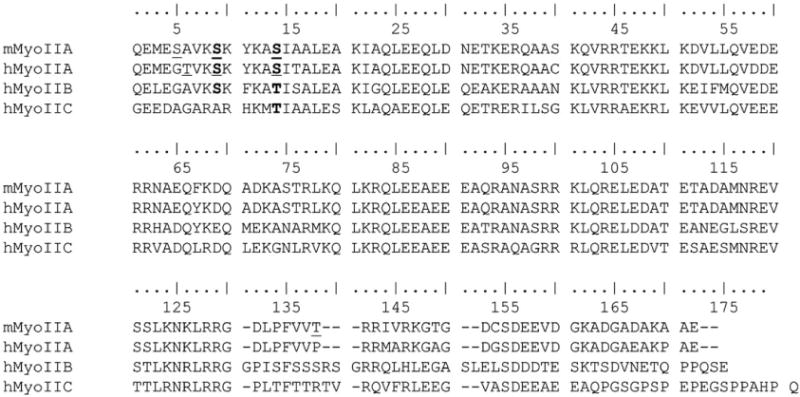

To address the differences in phosphorylation between mouse and human MHCIIA, we also analyzed mouse MHCIIA using LC-MS/MS. We detected several phosphopeptides and mapped the phosphorylation sites to Ser1799, Ser1803 and Thr1931. Notably, Thr1931 is present in the nonhelical tail of mouse MHCIIA but not human MHCIIA (Fig. 7), which explains the differences observed in in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 3). Mutations of Ser1803 and Thr1931 led to a significant reduction in 32P incorporation, demonstrating that these two residues are the major phosphorylation sites in mouse MHCIIA (Fig. 6c and d). Alignment of the COOH-termini of MHCIIA, MHCIIB and MHCIIC shows that Ser1803 is conserved in myosin IIB, whereas Ser1808 is conserved in all three myosin II isoforms (Fig. 7). We conclude that TRPM7 phosphorylates a conserved stretch of amino acids in the coiled-coil domain of nonmuscle myosin II isoforms.

Fig. 7.

Conservation of phosphorylation sites between mouse, human and Dictyostelium myosin II. (a) Alignment of the mouse MHCIIA and human MHCIIA, MHCIIB and MHCIIC COOH-termini. The phosphorylation sites are underlined, and conserved amino acids are shown in boldface. Note that two of three residues in the conserved stretch of amino acids within the coiled-coil domain of human MHCIIAwere verified in mouse MHCIIA by LC-MS/MS. Alignment with human MHCIIB and MHCIIC reveals that the major phosphorylated residue in human MHCIIA, Ser1803, is conserved in MHCIIB but not in MHCIIC, whereas Ser1808 in mouse and human MHCIIA is conserved in both human MHCIIB and MHCIIC.

Mutation of phosphorylation sites affects filament stability and protein localization

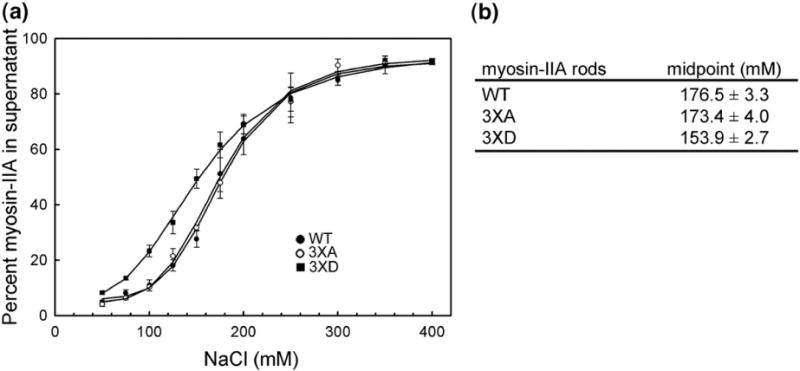

To investigate the consequences of phosphorylation on myosin IIA filament assembly, we generated myosin IIA rod constructs with the phosphorylation sites (Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808) mutated to alanine or aspartic acid. The WTand mutant myosin IIA rods were assembled into filaments at different NaCl concentrations, and the degree of solubility was measured. Myosin IIA rods containing phosphomimetic aspartic acid mutations showed increased solubility at physiological salt concentrations in comparison with WT myosin IIA and the alanine mutant (Fig. 8a). At 150 mM NaCl, 50% of the 3×D mutant remains in the supernatant, whereas only 25% of the WT myosin IIA as well as 3×A mutant is soluble. The differences in myosin IIA assembly between WT and 3×D rods are further demonstrated by the midpoint values (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Mutation of phosphorylation sites to aspartic acid affects myosin IIA filament stability. (a) The assembly of WT and mutant rods was monitored using a standard sedimentation assay. (●) WT; (○) 3×A; (▪)3×D. The solid lines represent the best fit to the Hill equation. (b) Midpoint measurement for WT and mutant myosin IIA rods. Data are reported as the mean±SEM for two to three independent experiments.

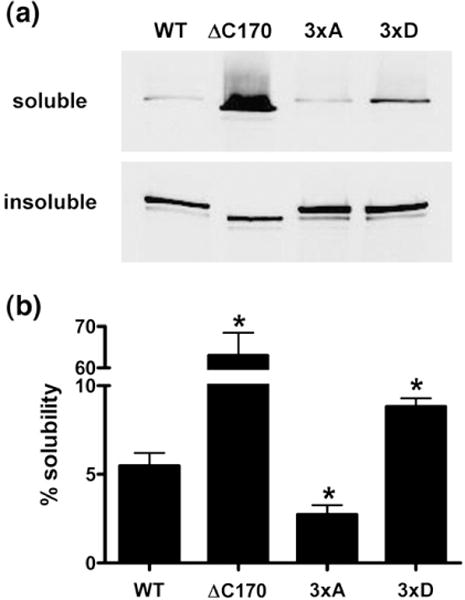

The same mutations were introduced into a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)–MHCIIA construct to study the effect of these phosphorylation sites on myosin IIA stability in vivo. In addition, the last 170 aa of the COOH-terminus in YFP–MHCIIA (ΔC170) were deleted to serve as a positive control for myosin IIA filament disassembly.33 Subsequently, these constructs were expressed in COS7 cells because they predominantly express MHCIIB and no MHCIIA. Western blotting showed that all constructs were expressed to similar levels in COS7 cells. However, biochemical fractionation of the cells revealed significant differences in the degree of filament assembly between the various MHCIIA mutants (Fig. 9). The majority of WT YFP–MHCIIA assembles into the actomyosin cytoskeleton, whereas deletion of the last 170 aa prevents this assembly. Notably, mutations of the phosphorylation sites to alanine (3×A) and aspartate (3×D) led to a decrease and an increase in YFP–MHCIIA solubility, respectively (Fig. 9b). These findings identify Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 as novel regulatory sites of myosin IIA filament assembly.

Fig. 9.

Mutation of phosphorylation sites to aspartate increases Triton solubility of myosin IIA. YFP–MHCIIA constructs were transiently transfected into COS7 cells. The cells were fractionated into Triton-soluble and -insoluble fractions. Equal amounts of these fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. Exogenous myosin IIA was detected using anti-GFP antibodies, followed by IRDye 800-coupled antimouse immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies. Fluorescence was measured using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. (a) Representative Western blot depicting the presence of YFP–MHCIIA mutants in the different fractions. (b) Quantification of the degree of solubility of each YFP–MHCIIA fusion protein. The data are presented as the percentage of soluble MHCIIA protein (mean±SEM, n=5). *p<0.05.

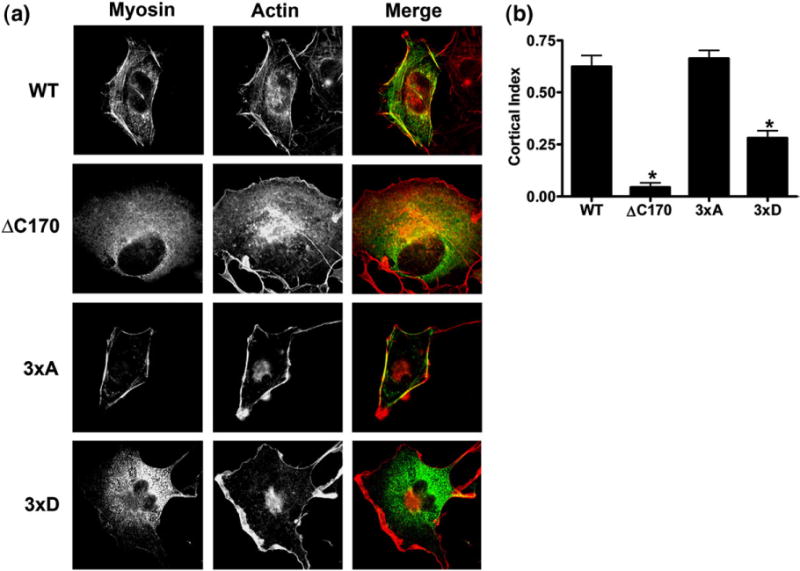

Based on the results of our biochemical experiments, we hypothesized that the various YFP–MHCIIA proteins have different distribution patterns in COS7 cells. Indeed, we observed that WT YFP–MHCIIA co-localized with the cortical filamentous actin (F-actin) cytoskeleton, whereas the ΔC170 mutant was homogenously distributed throughout the cytosol (Fig. 10a). Although the 3×A YFP–MHCIIA mutant also localized with the cortical F-actin cytoskeleton, the 3×D MHCIIA protein formed disorganized fibrillar assemblies within the cell body that failed to incorporate into cytoskeletal structures. In order to quantify differences observed between these myosin IIA tail mutants, we monitored the extent of cortical localization (cortical index), as was described earlier to determine sub-cellular localization of myosin IIB.26 Measurement of the cortical index confirmed the distribution of the various YFP–MHCIIA recombinant proteins, with both 3×D and ΔC170 mutants showing reduced cortical localization in comparison with WT myosin IIA and the 3×A mutant. These differences most probably reflect a differential ability of these mutants to incorporate into functional actomyosin assemblies (Fig. 10b). It should be noted that the distribution patterns of WT and mutant YFP–MHCIIA are consistent with filament stability observed in vitro. Notably, the ability of the 3×D MHCIIA mutant to self-assemble into disorganized fibrillar structures is represented by its relative insolubility in Triton X-100 in comparison with the deletion mutant ΔC170, but its inability to associate with cytoskeletal structures leads to an increase in solubility in comparison with WT MHCIIA. Thus, the different assays to monitor assembly of myosin IIA filaments both in vitro and in vivo are in good agreement. Phosphomimetic mutations lead to proteins that require lower NaCl concentrations to disrupt filaments in vitro, are more soluble in Triton X-100 and show lower cortical indices compared with WT MHCIIA in vivo. In contrast, mutations that prevent phosphorylation have the opposite effect. We therefore conclude that phosphorylation of Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 leads to a redistribution of the MHCIIA filaments in cells away from the cortex and prevents their incorporation into cytoskeletal structures.

Fig. 10.

Relocalization of YFP–MHCIIA 3×D mutant away from the cortex. (a) Representative images of COS7 cells expressing myosin IIA mutants. YFP–MHCIIA constructs were transiently expressed in COS7 cells. Subsequently, the actin cytoskeleton was stained using Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin and cellular localization of YFP–MHCIIA and F-actin was visualized by fluorescence microscopy. (b) Cortical index measurement of the myosin IIA mutants. The cortical index for 10 representative cells was measured as previously described. Data are presented as mean±SEM. *p<0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we addressed the molecular mechanism by which TRPM7 directly affects the activity of nonmuscle myosin IIA. We demonstrate that TRPM7 phosphorylates Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 in the coiled-coil domain of the MHCIIA and that phosphomimetic mutations introduced at these sites lead to the disassembly of myosin IIA filaments when expressed in cells. To the best of our knowledge, this study and another recent investigation36 are the first to show that phosphorylation of the MHCIIA affects filament assembly in vivo. Moreover, our results indicate a conservation of function between Dictyostelium and mammalian α-kinases.

We have chosen to investigate the effect of TRPM7 on the nonmuscle myosin IIA isoform rather than the myosin IIB or IIC isoforms for several reasons. First, both TRPM7 and myosin IIA are ubiquitously expressed, whereas myosins IIB and IIC have a more restricted expression pattern.12,37,38 For instance, both TRPM7 and myosin IIA are widely expressed in hematopoietic cells, whereas myosins IIB and IIC are absent. Second, previous work had shown that TRPM7 associates with the nonmuscle myosin IIA isoform in a Ca2+- and kinase-dependent manner, leading to actomyosin relaxation.28 Third, nonmuscle myosin IIA regulates cell adhesion in neuronal cells. Knockdown of myosin IIA but not myosin IIB leads to the disruption of focal adhesions formed in neuronal cells.39 Recently, we have shown that activation of TRPM7 leads to remodeling of adhesion structures in neuronal cells and that this phenotype can be mimicked by pharmacological inhibition of myosin II.28 Taken together, these results suggest that TRPM7 may be influencing myosin IIA function. However, we did observe that several phosphorylation sites (Ser1803, Ser1808) are conserved in myosins IIB and IIC. Therefore, we are currently addressing the potential role of TRPM7 in regulating myosins IIB and IIC.

TRPM7 associates with the actomyosin cytoskeleton where it phosphorylates the MHCIIA but not the associated myosin light chain (Supplementary Fig. S1). Here, we extend on these findings by demonstrating that TRPM7 phosphorylates the extreme COOH-terminus of the MHCIIA. Interestingly, this region of the MHCIIA is critical for filament assembly,33 and this can be regarded as an important regulatory domain. Net charge analysis of the MHCIIA shows that the region phosphorylated by TRPM7 lies within the only positively charged area of the coiled-coil domain (data not shown). This region was recently found to be critical to myosin IIB filament assembly,34 and, based on its charge, we predict that it will be highly responsive to phosphorylation. Accordingly, a number of protein kinases, including protein kinase C (PKC) and casein kinase II (CKII), have been found to phosphorylate this region of the helical tail, leading to a decrease in the critical salt concentration required to solubilize myosin IIA filaments in vitro.25 Moreover, point mutations that alter the charge composition of the MHCIIA tail affect myosin IIA filament assembly, leading to human disease.40 Finally, other regulatory proteins, such as S100A4, also target this area of the MHCIIA.20 Thus, TRPM7 specifically phosphorylates the region important for the regulation of myosin IIA filament formation.

Our experiments identify Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 as novel residues important for regulating myosin IIA assembly. These three TRPM7 phosphorylation sites are concentrated in a short stretch of amino acids, rather than being scattered throughout the COOH-terminus of the MHCIIA, demonstrating that the kinase reactions are highly specific. Moreover, the conservation of these residues across species and among nonmuscle myosin II isoforms provides further evidence that they represent important regulatory sites. Based on this conservation, we propose that Ser1803 and Ser1808 are expected to be the most important regulatory sites. Accordingly, we found that mutating Ser1803 was already sufficient to affect the subcellular localization and Triton X-100 solubility of MHCIIA (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3).

Although the differences in solubility between WT and mutant myosin IIA are relatively modest, they are highly reproducible. Importantly, mutation to alanine and that to aspartic acid produce opposite effects on myosin IIA filament stability, which strengthens the notion that these residues regulate filament-forming properties. A possible explanation for the relatively small differences between the various recombinant myosin IIA proteins is that the mutations, particularly, mutations to aspartic acid (3×D), may not fully mimic the phosphorylated state. Recently, Dulyaninova et al.36 could not recapitulate the phenotype of CKII-phosphorylated myosin IIA by mutation of the CKII target residues to aspartic acid. Thus, our aspartate mutants may give an underestimation of the effects of TRPM7-mediated phosphorylation on myosin IIA filament stability. Although most point mutations in the MHCIIA tail produce relatively modest effects on salt-assembly characteristics, these mutations can have a large impact on cell behavior and the pathogenesis of human disease. Several (point) mutations that cause MYH9-related diseases have been identified in myosin IIA.41,42 These single amino acid substitutions are found mainly in the coiled-coil domain. While most of these mutations produce minor effects on myosin IIA solubility, they do effectively interfere with organization of the monomers into filaments.40 Thus, we cannot exclude that TRPM7-mediated phosphorylation of mammalian nonmuscle myosin IIA has a greater impact on the organization of the filaments in vivo than measured by its solubility in vitro. Accordingly, the small increase in solubility of myosin IIA indicates that the majority of the 3×D mutant retains some kind of filamentous organization. This phenotype is reminiscent of that described by Dulyaninova et al.,36 who found that the S1934D mutant still associates with endogenous myosin IIA. Nevertheless, we clearly demonstrate a distinct subcellular distribution of the recombinant myosin IIA proteins in line with previous reports.26,43 Our findings and those of others indicate that future work is necessary to understand exactly how phosphorylation affects the organization and turnover of myosin II filaments in vivo.

The importance of heavy chain phosphorylation to myosin IIA filament stability remains controversial. Initial studies reported that myosin IIA filament assembly was predominantly regulated by S100A4 binding, whereas myosin IIB was regulated by heavy chain phosphorylation.44,45 More recently, it was demonstrated that phosphorylation of the MHCIIA by CKII and PKC isoforms leads to filament disassembly in vitro.25 Moreover, phosphorylation of the PKC site in myosin IIA correlates with exocytosis, suggesting a role for MHCIIA phosphorylation in regulated secretion.46 Our results clearly demonstrate that phosphorylation of the MHCIIA affects filament assembly in vivo. Mutation of TRPM7 phosphorylation sites to aspartic acid in MHCIIA reduces the incorporation of myosin IIA into the actomyosin cytoskeleton, leading to a relocalization of the protein away from the cortex. While myosins IIA and IIB are both regulated by heavy chain phosphorylation, important differences exist between the two isoforms. For instance, PKC phosphorylates myosin IIA in the coiled-coil domain, whereas it phosphorylates myosin IIB in the nonhelical tail.44,47 Moreover, different signaling pathways control the assembly of each myosin II isoform as the kinetics of myosins IIA and IIB phosphorylation upon agonist stimulation of mammalian cells differ and separate members of the PKC family, specifically, phosphorylated myosins IIA and IIB.26,27,45 We conclude that both myosins IIA and IIB are regulated by heavy chain phosphorylation in vivo but that specific signaling pathways control the assembly of these different myosin II isoforms.

To date, we have observed no global change in myosin IIA phosphorylation in response to TRPM7 activation (Supplementary Fig. S4). This result is not surprising since myosin IIA is constitutively phosphorylated on multiple sites, making it difficult to detect changes in 32P incorporation of a single site. In fact, detecting the phosphorylation of a particular site on myosin II generally requires the mutation of several residues that are phosphorylated by other kinases.27 Moreover, the TRPM7 kinase is low in abundance relative to other kinases. Based on the low expression levels, we do not believe that TRPM7 is responsible for the global regulation of myosin IIA dynamics in mammalian cells and that additional mechanisms are in place for this purpose. Instead, we propose that it affects myosin IIA locally. Accordingly, TRPM7 is enriched in cell adhesion structures, including podosomes.28,48 Activation of TRPM7 may generate local relaxation of the actomyosin cytoskeleton in close proximity to adhesion structures, leading to remodeling of focal adhesions and podosomes.28 Our current efforts are aimed at defining the cellular context in which phosphorylation of Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808 by TRPM7 has its strongest effects.

Both TRPM7 and PKC phosphorylate the MHCIIA α-helical tail. Since TRPM7 and PKC are activated by phospholipase C-mediated phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis,29,49 it is possible that both kinases synergize to regulate myosin IIA filament formation. Notably, activation of TRPM7 and that of PKC lead to the remodeling of adhesion structures and de novo formation of podosomes, which requires inhibition of myosin II activity.28,50 It will therefore be interesting to investigate how the different kinase pathways cooperate to provide temporal and spatial regulation of myosin II filament stability and localization in cells. The development of phosphospecific antibodies against the TRPM7, PKC and CKII sites will be essential to address this issue. Ultimately, antibodies that allow in situ detection of phospho-MHCIIA will provide further insight into the dynamics of the actomyosin cytoskeleton in mammalian cells.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that TRPM7 regulates myosin IIA filament stability and protein localization by phosphorylating the heavy chain. Moreover, our results identify novel residues, Thr1800, Ser1803 and Ser1808, that regulate myosin IIA filament assembly in vivo. Future experiments will be aimed at understanding the spatial and temporal organization of signaling networks controlling MHCIIA phosphorylation in mammalian cells.

Materials and Methods

Constructs

The retroviral vector encoding the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged WTand KD TRPM7 kinase domain (HA-TRPM7-C; amino acids 1158–1864) was previously described.28 Mouse MHCIIA fragments (Fig. 1) were amplified by reverse transcription PCR using RNA isolated from N1E-115 cells and cloned in-frame in pGEX-1N using BamHI and EcoRI sites. Human MHCIIA fragments fused to GST were generated as described for mouse MHCIIA constructs, but the cDNA was amplified by PCR using the pTRE-GFP (green fluorescent protein)–MHCIIA construct (kind gift of Robert Adelstein, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) as template. The vector pTRE-GFP–MHCIIA contains a Tet-responsive element,33 which allows the inducible expression of GFP–MHCIIA in mammalian cells; however, in our hands, expression in different cell lines was inefficient. Therefore, MHCIIA was excised using HindIII and SpeI sites and cloned into pEYFP-C3, which contains a cytomegalovirus promoter. YFP–MHCIIA was digested with AflII and SpeI, Klenow filled and ligated to generate the ΔC170 mutant. The construct encoding myosin IIA rod in the pET28a vector was previously described.20 All point mutations were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture

RBL-2H3 and COS7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal calf serum. Stable RBL-2H3 cell lines expressing WT and KD HA-TRPM7-C were generated by retroviral transduction.51 Cells were selected by the addition of 0.8 mg/ml of G418 to the media, and the selection was complete within 7 days. For transient protein expression, COS7 cells were transfected using either the diethylaminoethyl–dextran method or FuGENE 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

GST fusion protein purification

GST fusion proteins were induced in BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli by the addition of 200 μM IPTG and incubating the culture at 37 °C for 3 h. Bacteria were washed and subsequently resuspended in ice-cold GST lysis buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.5 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors]. Bacteria were incubated on ice for 15 min in the presence of lysozyme (100 μg/ml) to degrade the cell wall. The bacteria were lysed by sonication, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The GST fusion proteins were isolated by incubating the supernatant with glutathione–Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed in GST lysis buffer, and GST fusion proteins were eluted in elution buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM reduced glutathione and 1 mM DTT). Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay. For long-term storage, proteins were frozen in the presence of 10% glycerol at −80 °C.

In vitro kinase assays

WT and KD HA-TRPM7-C were purified from mammalian cells by immunoprecipitation. Cells were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors). Debris was removed by centrifugation, and TRPM7 kinase was isolated by immunoprecipitation using anti-HA antibodies (12CA5) coupled to protein G–Sepharose. TRPM7 immune complexes were washed and resuspended in IVK buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 4 mM MnCl2 and 2 mM DTT) with 2 μg of GST fusion proteins. The kinase reactions were initiated by adding ATP (100 μM cold ATP plus 5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP) and incubating at 30 °C for 30 min. Kinase reactions were stopped by the addition of Laemmli buffer containing 40 mM EDTA. Samples were boiled and separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. Quantification was performed by phosphorimager analysis.

Edman sequencing and MALDI–TOF MS

Residues phosphorylated by TRPM7 in MHCIIA were determined by a combination of solid-phase Edman sequencing and MS. Mapping of phosphorylation sites by Edman degradation sequencing and MS analysis of 32P-labeled peptides were performed as previously described.52

Phosphopeptide analysis by LC-MS/MS

Tryptic and GluC digests of phosphorylated myosin IIA were purified and desalted using C18 STAGE tips53 before analysis by MS. Peptide identification experiments were performed using a nano-HPLC Agilent 1100 nanoflow system connected online to a 7-T LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Bremen, Germany). Peptides were separated on 15-cm 100-μm ID PicoTip columns (New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA) packed with 3-μm Reprosil C18 beads (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany) using a 90-min gradient from 10% buffer B to 40% buffer B (buffer B contains 80% acetonitrile in 0.5% acetic acid), with a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Peptides eluting from the column tip were electrosprayed directly into the mass spectrometer with a spray voltage of 2.1 kV. Data acquisition with the LTQ-FT was performed in a data-dependent mode to automatically switch between MS, MS2 and neutral loss-dependent MS3 acquisitions. Briefly, full-scan MS spectra of intact peptides (m/z 350–2000) with an automated gain control accumulation target value of 106 ions were acquired in the FT ion cyclotron resonance cell with a resolution of 50,000. The four most abundant ions were sequentially isolated and fragmented in the linear ion trap by applying collisionally induced dissociation using an accumulation target value of 10,000 (capillary temperature=100 °C; normalized collision energy=30%). A dynamic exclusion of ions previously sequenced within 180 s was applied. All unassigned charge states and singly charged ions were excluded from sequencing. A minimum of 50 counts was required for MS2 selection. Data-dependent neutral loss scanning of phosphoric acid groups was enabled for each MS2 spectrum among the three most intense fragment ions. RAW spectrum files were converted into a Mascot generic peak list by DTA Supercharger.† Accurate parent masses of MS3 spectra were automatically generated by DTA Supercharger from the full FT MS scan. Peptides and proteins were identified using the Mascot (Matrix Science) search engine version 2.0 to search a local version of the human International Protein Index database version 3.05 supplemented with the sequences of GST–myosin IIA fusion proteins. The settings for Mascot searches were 10-ppm tolerance for the parental peptide and 0.5 Da for fragmentation spectra, a fixed carbamidomethyl modification for cysteines, variable modifications for oxidation of methionine, deamidation for glutamine and asparagine and phosphorylation for serine, threonine and tyrosine. Verification and site mapping of phosphorylated peptides were performed using the posttranslational modification scoring algorithm of MSQuant†, according to the procedure of Olsen et al. for phosphopeptides.54 As a final verification step, peptides containing phosphorylation sites occurring only once or twice were verified by manual inspection of the MS2 and MS3 spectra.

Myosin IIA filament assembly

WT and mutant myosin IIA rods were purified as previously described.20 The assembly properties of the myosin IIA rods were characterized in the presence of magnesium as described by Dulyaninova et al.25 The solubility data were plotted as a function of NaCl concentration and fit to the Hill equation in order to compare the midpoint of the curves for WT and mutant rods.

Cytoskeletal extraction

COS7 cells were transiently transfected with YFP–MHCIIA constructs 24 h prior to the experiment. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in cytoskeletal extraction buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml of aprotinin and 2 μg/ml of leupeptin) for 10 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000g to remove any insoluble material. Laemmli buffer was added to the supernatant. The purified cytoskeletons were first washed twice with cytoskeletal extraction buffer and proteins were solubilized in Laemmli buffer to solubilize the Triton-insoluble fraction. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 6% gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. YFP–MHCIIA proteins were detected using anti-GFP (1:1000; Roche) antibodies followed by IRDye 800CW-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:5000; Westburg). The fluorescence intensity of each band was quantified with the use of an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Microscopy

COS7 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and transfected with YFP–MHCIIA constructs. On the following day, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 3 min and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin/PBS. Cells were incubated with Texas Red-labeled phalloidin (1:200; Molecular Probes) for 45 min to detect F-actin. Cells were washed three times with PBS between each step. Cells were viewed using a Leica DMRA microscope with a ×63, 1.32-NA oil immersion lens. Cortical index was measured as previously described.26

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean±SEM. The statistical significance of differences between experimental groups was assessed with Student’s t test. Differences in means were considered significant if p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a FEBS Short-Term Fellowship to K. C. and a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society to C. G. F., W. H. M. and F. N. v. L. We thank Dr. Robert Adelstein (National Institutes of Health) for providing reagents and Niels Peterse for providing technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- MHCII

myosin II heavy chain

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- WT

wild type

- KD

kinase dead

- MALDI–TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight

- MS

mass spectrometry

- LTQ-FT

linear ion trap quadrupole–Fourier transform

- LC-MS/MS

nano-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- PKC

protein kinase C

- CKII

casein kinase II

- HA

hemagglutinin

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j. jmb.2008.02.057

References

- 1.Vogel V, Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Small JV, Resch GP. The comings and goings of actin: coupling protrusion and retraction in cell motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumura F. Regulation of myosin II during cytokinesis in higher eukaryotes. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foth BJ, Goedecke MC, Soldati D. New insights into myosin evolution and classification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3681–3686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506307103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupton SL, Waterman-Storer CM. Spatiotemporal feedback between actomyosin and focal-adhesion systems optimizes rapid cell migration. Cell. 2006;125:1361–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingber DE. Mechanobiology and diseases of mechanotransduction. Ann Med. 2003;35:564–577. doi: 10.1080/07853890310016333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krendel M, Mooseker MS. Myosins: tails (and heads) of functional diversity. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:239–251. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00014.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hostetter D, Rice S, Dean S, Altman D, McMahon PM, Sutton S, et al. Dictyostelium myosin bipolar thick filament formation: importance of charge and specific domains of the myosin rod. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:1880–1892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bao J, Jana SS, Adelstein RS. Vertebrate nonmuscle myosin II isoforms rescue small interfering RNA-induced defects in COS-7 cell cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19594–19599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golomb E, Ma X, Jana SS, Preston YA, Kawamoto S, Shoham NG, et al. Identification and characterization of nonmuscle myosin II-C, a new member of the myosin II family. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2800–2808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolega J. Asymmetric distribution of myosin IIB in migrating endothelial cells is regulated by a rho-dependent kinase and contributes to tail retraction. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4745–4757. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolega J. The role of myosin II motor activity in distributing myosin asymmetrically and coupling protrusive activity to cell translocation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4435–4445. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenfeld SS, Xing J, Chen LQ, Sweeney HL. Myosin IIb is unconventionally conventional. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27449–27455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KY, Kovacs M, Kawamoto S, Sellers JR, Adelstein RS. Disease-associated mutations and alternative splicing alter the enzymatic and motile activity of nonmuscle myosins II-B and II-C. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22769–22775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jana SS, Kawamoto S, Adelstein RS. A specific isoform of nonmuscle myosin II-C is required for cytokinesis in a tumor cell line. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24662–24670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs M, Wang F, Hu A, Zhang Y, Sellers JR. Functional divergence of human cytoplasmic myosin II: kinetic characterization of the non-muscle IIA isoform. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38132–38140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Kovacs M, Hu A, Limouze J, Harvey EV, Sellers JR. Kinetic mechanism of non-muscle myosin IIB: functional adaptations for tension generation and maintenance. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27439–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li ZH, Spektor A, Varlamova O, Bresnick AR. Mts1 regulates the assembly of nonmuscle myosin-IIA. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14258–14266. doi: 10.1021/bi0354379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tullio AN, Accili D, Ferrans VJ, Yu ZX, Takeda K, Grinberg A, et al. Nonmuscle myosin II-B is required for normal development of the mouse heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12407–12412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conti MA, Even-Ram S, Liu C, Yamada KM, Adelstein RS. Defects in cell adhesion and the visceral endoderm following ablation of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain II-A in mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41263–41266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrett SC, Varney KM, Weber DJ, Bresnick AR. S100A4, a mediator of metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:677–680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dulyaninova NG, Malashkevich VN, Almo SC, Bresnick AR. Regulation of myosin-IIA assembly and Mts1 binding by heavy chain phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6867–6876. doi: 10.1021/bi0500776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg M, Ravid S. Protein kinase Cgamma regulates myosin IIB phosphorylation, cellular localization, and filament assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1364–1374. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Even-Faitelson L, Ravid S. PAK1 and aPKCzeta regulate myosin II-B phosphorylation: a novel signaling pathway regulating filament assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2869–2881. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark K, Langeslag M, van Leeuwen B, Ran L, Ryazanov AG, Figdor CG, et al. TRPM7, a novel regulator of actomyosin contractility and cell adhesion. EMBO J. 2006;25:290–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langeslag M, Clark K, Moolenaar WH, van Leeuwen FN, Jalink K. Activation of TRPM7 channels by phospholipase C-coupled receptor agonists. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:232–239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drennan D, Ryazanov AG. Alpha-kinases: analysis of the family and comparison with conventional protein kinases. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;85:1–32. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosgraaf L, van Haastert PJ. The regulation of myosin II in Dictyostelium. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De la Roche MA, Smith JL, Betapudi V, Egelhoff TT, Cote GP. Signaling pathways regulating Dictyostelium myosin. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2002;23:703–718. doi: 10.1023/a:1024467426244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei Q, Adelstein RS. Conditional expression of a truncated fragment of nonmuscle myosin II-A alters cell shape but not cytokinesis in HeLa cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3617–3627. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg M, Straussman R, Ben-Ya’acov A, Ronen D, Ravid S. MHC-IIB filament assembly and cellular localization are governed by the rod net charge. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buxton DB, Adelstein RS. Calcium-dependent threonine phosphorylation of nonmuscle myosin in stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34772–34779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dulyaninova NG, House RP, Betapudi V, Bresnick AR. Myosin-IIA heavy-chain phosphorylation regulates the motility of MDA-MB-231 carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3144–3155. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Runnels LW, Yue L, Clapham DE. TRP-PLIK, a bifunctional protein with kinase and ion channel activities. Science. 2001;291:1043–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.1058519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadler MJ, Hermosura MC, Inabe K, Perraud AL, Zhu Q, Stokes AJ, et al. LTRPC7 is a Mg.ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature. 2001;411:590–595. doi: 10.1038/35079092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wylie SR, Chantler PD. Separate but linked functions of conventional myosins modulate adhesion and neurite outgrowth. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:88–92. doi: 10.1038/35050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franke JD, Dong F, Rickoll WL, Kelley MJ, Kiehart DP. Rod mutations associated with MYH9-related disorders disrupt nonmuscle myosin-IIA assembly. Blood. 2005;105:161–169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seri M, Cusano R, Gangarossa S, Caridi G, Bordo D, Lo Nigro C, et al. Mutations in MYH9 result in the May–Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes. The May–Hegglin/Fechtner Syndrome Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26:103–105. doi: 10.1038/79063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelley MJ, Jawien W, Ortel TL, Korczak JF. Mutation of MYH9, encoding non-muscle myosin heavy chain A, in May–Hegglin anomaly. Nat Genet. 2000;26:106–108. doi: 10.1038/79069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Even-Faitelson L, Rosenberg M, Ravid S. PAK1 regulates myosin II-B phosphorylation, filament assembly, localization and cell chemotaxis. Cell Signalling. 2005;17:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murakami N, Kotula L, Hwang YW. Two distinct mechanisms for regulation of nonmuscle myosin assembly via the heavy chain: phosphorylation for MIIB and mts1 binding for MIIA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11441–11451. doi: 10.1021/bi000347e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straussman R, Even L, Ravid S. Myosin II heavy chain isoforms are phosphorylated in an EGF-dependent manner: involvement of protein kinase C. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3047–3057. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ludowyke RI, Elgundi Z, Kranenburg T, Stehn JR, Schmitz-Peiffer C, Hughes WE, Biden TJ. Phosphorylation of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA on Ser1917 is mediated by protein kinase C beta II and coincides with the onset of stimulated degranulation of RBL-2H3 mast cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:1492–1499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murakami N, Chauhan VP, Elzinga M. Two nonmuscle myosin II heavy chain isoforms expressed in rabbit brains: filament forming properties, the effects of phosphorylation by protein kinase C and casein kinase II, and location of the phosphorylation sites. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1989–2003. doi: 10.1021/bi971959a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su LT, Agapito MA, Li M, Simonson WT, Huttenlocher A, Habas R, et al. TRPM7 regulates cell adhesion by controlling the calcium-dependent protease calpain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11260–11270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512885200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brose N, Rosenmund C. Move over protein kinase C, you’ve got company: alternative cellular effectors of diacylglycerol and phorbol esters. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4399–4411. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burgstaller G, Gimona M. Actin cytoskeleton remodelling via local inhibition of contractility at discrete microdomains. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:223–231. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michiels F, van der Kammen RA, Janssen L, Nolan G, Collard JG. Expression of Rho GTPases using retroviral vectors. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25451-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campbell DG, Morrice NA. Identification of protein phosphorylation sites by a combination of mass spectrometry and solid phase Edman sequencing. J Biomol Tech. 2002;13:119–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rappsilber J, Ishihama Y, Mann M. Stop and go extraction tips for matrix-assisted laser desor7ption/ionization, nanoelectrospray, and LC/MS sample pretreatment in proteomics. Anal Chem. 2003;75:663–670. doi: 10.1021/ac026117i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.