Abstract

Aims

Currently, treatment for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) focuses on the cholinergic hypothesis and provides limited symptomatic effects. Research currently focuses on other factors that are thought to contribute to AD development such as tau proteins and Aβ deposits, and how modification of the associated pathology affects outcomes in patients. This systematic review summarizes and appraises the evidence for the emerging drugs affecting Aβ and tau pathology in AD.

Methods

A comprehensive, systematic online database search was conducted using the databases ScienceDirect and PubMed to include original research articles. A systematic review was conducted following a minimum set of standards, as outlined by The PRISMA Group 1. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were followed and studies fitting the criteria were selected. No human trials were included in this review. In vitro and in vivo AD models were used to assess efficacy to ensure studied agents were emerging targets without large bodies of evidence.

Results

The majority of studies showed statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) of Aβ and/or tau pathology, or cognitive effects. Many studies conducted in AD animal models have shown a reduction in Aβ peptide burden and a reduction in tau phosphorylation post-intervention. This has the potential to reduce plaque formation and neuronal degeneration.

Conclusions

There are many emerging targets showing promising results in the effort to modify the pathological effects associated with AD. Many of the trials also provided evidence of the clinical effects of such drugs reducing pathological outcomes, which was often demonstrated as an improvement of cognition.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ, emerging targets, systematic review, tau

Introduction

AD is an irreversible neurodegenerative disease that has crippling effects on the nervous system and consequently on daily life. It is the most common form of dementia, accounting for almost two thirds of dementia cases in the United Kingdom; affecting around 520 000 people in 2012 2.

AD pathophysiology

The underlying mechanisms of AD are still unconfirmed but the aggregation of tau proteins, Aβ deposits and decreased concentrations of acetylcholine are three of the current factors being considered to aid the production of new targets for AD therapies 3.

Tau pathophysiology

Tau is a protein, known as a microtubule-associated protein (MAP), and an integral part of neuronal stability as it helps to maintain the microtubules that form part of the neuron cytoskeleton. Tau is encoded by a gene located on chromosome 17q21 and undergoes splicing to produce various isoforms 4.

In AD, abnormal phosphorylation/hyperphosphorylation occurs causing tau to have a decreased affinity for microtubules, which results in the movement of tau proteins from the microtubule to the intracellular neuronal space. This leaves the microtubule unstable and it consequently starts to collapse. The hyper-phosphorylated free tau proteins move down the axon from where they dissociated from the microtubules and self-aggregate in the neuron cell body forming neurofibrillary tangles. This impairs axonal transport leading to dysfunction of the synapse and ultimately neuronal death 4.

The functions of the tau protein are regulated by various kinases. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) plays a role in the hyperphosphorylation of tau which is a key feature in AD. Phosphorylation of tau by GSK3 occurs at the microtubule binding domain, therefore reducing the extent to which tau can bind to microtubules and hence causes dissociation between the tau proteins and the microtubules 5.

Amyloid precursor protein and amyloid β pathophysiology

Aβ peptides are produced and released during normal synaptic activity in the brain via the catabolism of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by secretases in the neuronal membrane. It is thought that an excess amount of Aβ42 (which is the most toxic and amyloidogenic form of the peptide) is a key cause of cellular damage in AD. Aβ42 is produced during the second step of APP catabolism when the γ-secretase acts on the β-secretase product from step 1 of the catabolism 6. In a healthy brain, these fragments would be broken down and eliminated from the body. However in AD they are not sufficiently broken down and accumulate to form one of the typical characteristics of AD, amyloid plaques.

There are currently only four drugs recommended in the United Kingdom by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 7; three of which are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEi) and one a novel agent acting on the glutaminergic system, memantine.

This systematic review was conducted with the aim of summarizing, comparing and contrasting the evidence for the emerging targets and corresponding agents to treat AD. It focuses on the tau hypothesis and the amyloid hypothesis of AD to provide an overall review of the two most researched but undeveloped areas of AD therapeutics.

Methods

The PRISMA Guidelines 1 were followed in the search for relevant literature and the writing of this review to ensure an evidence-based minimum set of standards was fulfilled when compiling and presenting the evidence relevant to answer the research question.

Criteria for selecting studies

Types of studies

Studies included in this review included original research articles published by the corresponding researchers and did not include any review articles to ensure that studies were assessed individually and compared against the inclusion criteria for this specific review. This also prevented using another author’s conclusions in the report. The studies must have been published between the years of 2011–2014 and be assessing the use of novel agents targeting Aβ or tau for the treatment of AD in order to produce a systematic review of the most up-to-date, relevant trials. Articles were also only considered if they were written in the English language. Both published articles and accepted manuscripts were included.

Participants

No human trials were included in this study as it focused solely on the emerging drugs and targets for AD and therefore only used research conducted in vitro or in animal studies. This ensured the information gathered was the most recent and was not focused on well-established trial agents that have large bodies of evidence. The animals involved in the studies in this report were transgenic mice and rats, therefore providing a suitable AD model for the novel agents to be tested upon.

Interventions

Any agent targeted towards either Aβ or tau used in the treatment of AD was classed as an intervention regardless of dose. However, the drug must be used in an AD model and not on healthy tissue in vitro or in healthy animals otherwise the results cannot be compared with AD itself.

Outcome measures

Outcomes were measured as a change in the pathological features of AD, for example, a reduction in tau aggregation or a stabilization in microtubules, and as a change in cognition if conducted in animals. As the studies were not conducted in humans, the level of cognition in terms of recognized scoring systems, such as the change in score of the Mini Mental State Examination could not be measured and was therefore based on other methods, for example, the Morris water maze test.

Bias

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was assessed, using the ‘Model Quality Assessment Instrument for Animal Studies’ 8 as outlined in their review of assessment tools for published animal studies, for all studies included in this review. Five main types of bias were assessed with a decision made as to the risk of bias. Bias was assessed as low risk, high risk or unclear risk if there was insufficient evidence to make a conclusion.

Information sources

A systematic online database search was conducted in January 2014 using the online databases ScienceDirect and PubMed to include original research articles only. The databases were last searched on March 2, 2014.

Search

The full electronic search strategies are outlined in Table1.

Table 1.

ScienceDirect and PubMed electronic searches are compared

| ScienceDirect | PubMed |

|---|---|

| Advanced search | MeSH Database |

| Search for: ((Alzheimer’s AND novel AND therapy) AND (tau OR Aβ OR amyloid or APP)) in all fields | ((‘Alzheimer Disease/drug therapy’ [Mesh]) AND ‘tau proteins’ [Mesh]) AND ‘Amyloid beta-Peptides’ [Mesh] |

| Refined to: Articles | Limited to: Journal articles and in vitro |

| Years: 2011 to present | Species: Other animals |

| Returned 567 results | Language: English |

| Years: 01/01/2011 – 02/03/2014 | |

| Returned 42 results |

Results

Data collection process

Study selection

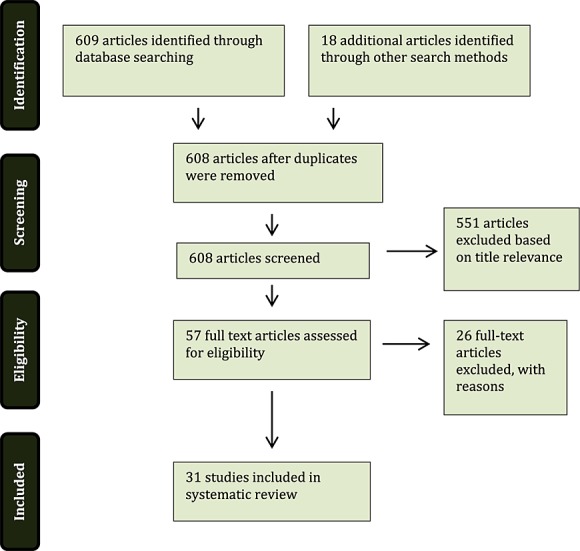

Studies were selected from the initial combined 608 results (after removing duplicates) based on their title relevance and being original research articles. Fourteen studies were selected from the PubMed MeSH database search and the others excluded based on irrelevant titles. Irrelevance was defined as any study not being directly associated with tau proteins or Aβ/amyloid beta-peptides and therefore many results were not included as they were based on AChEis or the cholinergic hypothesis of AD. Forty-three articles were deemed relevant, based on title, from the ScienceDirect database search. A total of 31 studies were included in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm of the method followed to identify the studies to be included in the review (adapted from The PRISMA Group 1)

Study characteristics

Characteristics of included studies

The studies included in this systematic review were assessed and described in terms of the type of study, the intervention strategy used and outcomes/results specifically in terms of Aβ pathology, tau pathology and cognitive effects (Table2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Study type | Intervention | Outcomes/Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ | Tau | Cognitive effects | |||

| Agbemenyah et al. 33 | In vivo animal study (using APPPS1-21 and wild type mice) | In vivo study: bilateral hippocampal injections of 1 µl, at a rate of 0.25 µl min–1, IGFBP7 (0.5 µg µl–1), IGFBP7 blocking antibody (1μg µl–1) or IgG (dissolved in sterile 0.1% BSA in sterile PBS). | – | – | Significantly reduced escape latency in APPPS1-21 mice compared with wild type mice (P < 0.0001, F=26.68), memory impairment was reduced following administration of IGFBP7 blocking antibody. |

| Barron et al. 16 | In vivo animal study (using 3xTg-AD) | Ro5-4864 (3 mg kg–1) was administered to young adult, (gonadectomized (GDX) and sham GDX) by injection once weekly for 3 months and aged 3xTg-AD mice injected for 4 weeks. A vehicle (1% DMSO in canola oil) was used as a control. | Aβ load was reduced by nearly 50% in GDX mice compared with vehicle.In adult mice, Aβ load was reduced by >50% (P = 0.03). | – | Ro5-4864 treated mice exhibited a decrease in anxiety-related behaviour – with a significant decrease in aged 3xTg-AD mice (P = 0.03). |

| Bitner et al. 26 | In vivo animal study (using CD1, Tg2576 and TAPP, nAChR knockout (KO) and wild type mice). | CD1 mice received varying doses of ABT-239 (0.03, 0.1, 1.0 mg kg–1). Tg2576 and TAPP mice received ABT-239 (0.7 mg kg–1 day–1) or sterile water for 14 days by subcutaneous (s.c.) infusion. Wild type and nAChR KO mice received ACT-239 (1.0 mg kg–1) or sterile water. | – | There was a significant reduction in phosphorylated tau immunoreactivity, in ventral horn motorneurons, in TAPP mice treated with ABT-239 continuously (0.7 mg kg–1 day–1) | – |

| Camboni et al. 15 | In vivo animal study (using APPswePSEN1dE9 mice and non-transgenic littermates, both young and aged). | Both young and old APPswePSEN1dE9 mice were administered SDPM1-4E peptide 100 µg conjugated to 25 µg ALUM by s.c. injection once every 2 weeks for a total of four injections. | ≥50% decrease in Aβ plaque burden was observed in both young and aged transgenic mice following vaccination with SDPM1-4E peptide. A decrease in the size of plaques and the number of plaques was also observed. | – | Both young and aged transgenic mice, following SDPM1-4E vaccination, exhibited similar memory levels to those observed in wild type mice. |

| Chen et al. 36 | In vitro study (using day E18 Wistar rat embryo hippocampal neurons). | 8 day neurons were treated with glucose-BSA + Ex-4 or GLP-1 (100 nm); glucose-BSA + LiCl (4 m m); BSA; glucose-BSA for 24 h. | – | A reduction in high glucose-induced tau hyperphosphorylation was noted in rat neurons treated concurrently with Ex-4 or GLP-1. | – |

| Cioanca et al. 34 | In vivo animal study (using 3 month old male Wistar rats). | Aβ(1-42)alone; Aβ(1-42) + volatile coriander oil 1%; Aβ(1-42) + volatile coriander oil 3%; saline (0.9% NaCl). Volatile coriander oil was inhaled for 21 days following surgery. | Fewer Aβ deposits were seen in the hippocampus of drug treated rats. | A significant improvement in spatial working memory (P < 0.001) was observed in drug treated groups. | |

| Corona et al. 23 | In vivo animal study (using 3xTg-AD mice and control PS1-KI mice). | 3xTg-AD mice received 10 m m carnosine supplementation in drinking water for 11–13 months. Control groups received tap water. | Mice treated with carnosine showed significantly reduced amyloid load in the hippocampus. | No reduction in phosphorylated tau immunoreactivity was evidenced in this study. | Untreated 3xTg-AD demonstrated worsening long-term memory compared with treated mice (P < 0.05). Deficits in long-term memory in 3xTg-AD mice were not significantly improved in treated groups. |

| DeMattos et al. 31 | In vivo animal study (using PDAPP mice). | Antibodies: mE8-IgG1; 3D6; IgG2a; mE8-IgG2a. 12.5 mg kg–1 of each antibody was administered every week for 3 months to aged PDAPP mice. | Aβ42 was reduced by ∼53% and ∼38% by mE8-IgG2a and mE8-IgG1, respectively.A significant reduction in Aβ42 was seen by mE8-IgG1 compared with time zero mice (P < 0.0066). | – | – |

| Durairajan et al. 21 | In vivo animal study (using TgCRND8 mice). | TgCRND8 mice received oral berberine (BBR) 25 mg kg–1 day–1 or 100 mg kg–1 day–1 or vehicle for 4 months. | A significant reduction in the area occupied by Aβ deposits was noted in BBR treated mice with 25 mg kg–1 day–1 and 100 mg kg–1 day–1 (61% (P < 0.001) and 43% (P < 0.05) reduction in area, respectively). | Western blot analysis showed 26%, 30% and 42% reduction in phosphorylated tau at the PHF-1, AT8 and AT180 antibodies in BBR treated transgenic mice compared with untreated controls. | BBR treatment improved spatial learning significantly in TgCRND8 mice compared to placebo treated TgCRND8 mice (P< 0.001). |

| Farr et al. 22 | In vivo animal study (using SAMP8 mice). | Three treatments at weekly intervals of either GSK antisense oligonucleotide (GAO) 60 ng 2 µl–1 or random antisense oligonucleotide (RAO) 60ng 2 µl–1. | A significantly lower level of phosphorylated tau was recorded in the brain of GAO treated SAMP8 mice compared with RAO treated SAMP8 mice (P < 0.01). | GAO improved learning and memory by significantly improving the number of trials taken to reach first avoidance compared with RAO (P < 0.05). | |

| Geekiyanage et al. 9 | In vivo animal study (using TgCRND8 mice). | Treatment group – 10 mg kg–1 LCS s.c. (whilst being fed the D12492 diet)Control groups – D12492 diet group; control chow diet group. | A significant decrease in Aβ1-42 levels was seen in the LCS group compared with mice fed a high fat D12492 diet and a control diet (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively). | LCS group mice showed a decrease in cortical hyperphosphorylated tau compared with the high fat diet group and the control diet group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). | - |

| Giuliani et al. 35 | In vivo animal study (using 3xTg-AD and wild type mice). | NDP-α-MSH 340 µg kg–1 day–1 (dissolved in saline 1 ml kg–1) with HS024 (130μg/kg in saline 1 ml kg–1) pre-treatment, once daily for 18 weeks; controls received equal volumes of saline; additional controls – wild type mice treated with NDP-α-MSH/ HS024 alone, 3xTg-AD mice treated with HS024 alone. | The frontal cortex and hippocampus had fewer Aβ deposits in 3xTg-AD mice treated with NDP-α-MSH compared with saline-treated 3xTg-AD mice. | The level of phosphorylated tau was decreased in NDP-α-MSH treated 3xTg-AD mice when compared with saline-treated 3xTg-AD mice. | A significant improvement in learning and memory was seen in 3xTg-AD mice treated with NDP-α-MSH compared with saline-treated 3xTg-AD mice. |

| Hoppe et al. 12 | In vivo animal study (using male Wistar rats). | Treatment groups – injected with Aβ(1-42) and treated with curcumin - Cur 50 (curcumin 50 mg kg–1 day–1) and Cur-LNS 2.5 (curcumin 2.5 mg kg–1 day–1) for 10 days.Control groups (injected with water plus 0.1% ammonium hydroxide) were untreated or treated with free curcumin in 0.05% carboxymethylcellulose. | – | Treatment with Cur 50 and Cur-LNS 2.5 significantly decreased tau phosphorylation P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). | Curcumin treatment significantly increased spontaneous alternation behaviour (P < 0.05) compared with those that did not receive treatment. |

| Inestrosa et al. 10 | In vivo animal study (using APPswe/PSEN1dE9 mice). | APPswe/PSEN1dE9 mice were injected with 4 mg kg–1 IDN5706 3 times per week for 10 weeks; control – injected with vehicle. | IDN5706-treated mice showed a significant reduction in Aβ burden compared with controls. There was also a reduction in Aβ oligomers in the cortex and hippocampus when compared with controls. | IDN5706-treated mice showed a decreased level of phosphorylated tau compared with control mice. | Spatial learning was improved in IDN5706-treated mice as shown by decreased latency times and reduced swimming path in the Morris water maze test. |

| Kang et al. 37 | In vitro study (using APPswe plasmid transfected HEK293 cells). | Ecklonia cava extract 5 µg ml–1, 10 µg ml–1, 25 µg ml–1 and 50 µg ml–1. | Ecklonia cava significantly reduced the secretion of Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 in APPswe cells. | – | – |

| Kang et al. 6 | In vitro study (using APPswe plasmid transfected HEK293 cells and 16 day rat embryonic brain cortical neurons). | HEK293 cells treated with Ecklonia cava extract 5 µg ml–1, 15 µg ml–1 and 50 µg ml–1 for 7 days.16 day rat embryonic brain cortical neurons treated with Ecklonia cava extract50 µg ml–1 pre- or post-incubation. | Ecklonia cava reduced Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 in APPswe cells to 50% of the untreated-control. Ecklonia cava inhibits Aβ formation as observed by a significant reduction in Aβ multimer formation in APPswe cells.16 day rat embryonic brain cortical neurons showed a significant decrease in cell death when pre-treated with Ecklonia cava. | – | – |

| Kashiwaya et al. 27 | In vivo animal study (using 3xTg-AD mice). | 3xTg-AD mice received either a ketone ester diet (KET-diet) or a carbohydrate-enriched diet (CHO-diet) of 4–5g daily for 8 months. NIH-31 chow pellets were supplemented to maintain body weight. | KET-diet mice showed a decrease in Aβ presence in the hippocampus, amygdala and subiculum compared with CHO-diet mice. | There were significantly less phosphorylated-tau positive neurons present in KET-diet mice compared with CHO-diet mice. | There was a significant decrease in escape latency, in the Morris water maze test, observed in mice treated with the KET-diet compared with the CHO-diet (P = 0.026). |

| Lo et al. 17 | In vivo animal study (using APPPS1-21 mice and wild type mice). | In vivo – APPPS1-21 mice were fed a diet containing 1 mg kg–1, 5 mg kg–1 or 20 mg kg–1 SEN1500 (treatment group) for 4 months; APPPS1-21 mice were fed regular food pellets (control). | Soluble and insoluble Aβ was not significantly reduced in the hippocampal and cortical regions of APPPS1-21 SEN1500 treated mice, and showed little difference to untreated APPPS1-21 mice. | – | Treated APPPS1-21 mice showed significant improvement in spatial working memory (P < 0.001) compared with untreated APPPS1-21 mice. |

| Niedowicz et al. .38 | In vivo animal study (using APPdNLhxPS1P264L knock in mice) and in vitro study (using over-expressed APPdNLh H4 neuroglioma cells). | In vivo study – APPdNLhxPS1P264L mice were fed a ketogenic diet (80% fat); western diet (40% fat) or control diet (20% fat) ad libitum for 1 month.In vitro study – over-expressed APPdNLh H4 neuroglioma cells were treated with leptin 10 ng ml–1 and 50 ng ml–1 for 24 h. | In vivo study – treatment diets increased leptin levels significantly (P = 0.02) but did not have a significant effect on Aβ levels in the brain (P = 0.66).In vitro study – Aβ generation was decreased in cells treated with leptin in a dose dependent manner. | – | – |

| Nikkel et al. 28 | In vivo animal study (using 3xTg-AD; CD1; Balb/c and NMRI mice). | CD1 – pre-treatment with A-705253 10 mg kg–1 or saline 10 mg kg–1 prior to induction of tau phosphorylation.Balb/c – pre-treatment with A-705253 5 mg kg–1 or saline 10 mg kg–1 30 min prior to LPS 5 mg kg–1 administration, a second saline injection was given as a control.3xTg-AD - A-705253 80 mg kg–1 day–1 in drinking water for 2 weeks. | – | A-705253 alone did not affect tau phosphorylation.A-705253 prevented LPS-induced tau phosphorylation when given as pre-treatment. | – |

| O’Hare et al. 18 | In vivo animal study (using Sprague-Dawley rats). | Control groups received either vehicle (maple syrup) plus Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) conditioned medium (CM), 20 mg kg–1 SEN1500 plus CHO CM or vehicle with 7PA2 CM. Treatment groups received SEN1500 1 mg kg–1, 5 mg kg–1 or 20 mg kg–1 plus 7PA2 CM. | – | – | Pre-treatment with SEN1500 had a significant improvement on incorrect lever perseverations (P = 0.0001). A dose dependent improvement in memory in rats was observed. |

| Perez-Gonzalez et al. 24 | In vivo animal study (using APP/PS1 mice and wild type controls) and in vitro study (using day 17 embryonic Wistar rat cortical and hippocampal neurons). | In vivo study - S14 5mg kg–1 day–1 or vehicle (5%DMSO) control was administered to mice for 4 weeks.In vitro study – day 17 embryonic Wistar rat cortical and hippocampal neurons received S14 treatment (30 μ m) and Aβ1-42 (10 μ m) for 24 h. | Aβ accumulation and Aβ occupied brain area was reduced significantly in APP/PS1 mice treated with S14.Cortical and hippocampal neurons treated with S14 showed reduced Aβ cytotoxicity and cell death. | A decrease in hyperphosphorylated tau was observed in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice treated with S14. | APP/PS1 S14 treated mice had a similar, improved recognition index when compared with wild type mice in the novel object recognition task. |

| Qin et al. 39 | In vivo animal study (using male Sprague-Dawley rats). | Rats received 0.5 ml Cy3G or saline 10 mg kg–1 daily for 30 days following either sham or Aβ surgery. | – | Aβ/Cy3G treated rats had decreased levels of phosphorylated tau compared to Aβ rats that were untreated. | Aβ/Cy3G treated rats had decreased escape latencies compared with controls. |

| Ramalho et al. 19 | In vivo animal study (using APP/PS1 mice) and in vitro study (using 17/18 day Wistar rat foetus cortical and hippocampal neurons). | In vivo – TUDCA (0.4% w/w)-treated APP/PS1 mice; TUDCA (0.4% w/w)-treated wild type mice (control); untreated APP/PS1 mice (control) and untreated wild type mice (control) – treatment duration was 6 months.In vitro – neurons were incubated with Aβ1-42 2 μ m and treated with or without TUDCA using Aβ35-25 and Aβ42-1 as controls. | In vitro – TUDCA significantly prevented Aβ-induced cell death (P < 0.05). | – | – |

| Shytle et al. 11 | In vivo animal study (using Tg2576 mice) | Tg2576 mice received HSS-888 0.1% w/w in NIH-31 chow (treatment); THC 0.1% w/w in NIH-31 chow (treatment) or NIH-31 chow alone (control) for 6 months. | HSS-888 reduced Aβ deposition in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. | Soluble fractions of phosphorylated tau were decreased in brain homogenates. | – |

| Sierksma et al. 30 | In vivo animal study (using APPswe/PS1dE9 and wild type mice). | APPswe/PS1dE9 and wild type mice received GEBR-7b (5 ml kg–1) or vehicle (0.5% methyl-2-hydroxyethyl cellulose/0.005% DMSO) by daily injection for 3 weeks. | – | – | Neither treatment nor genotype affected y-maze spontaneous alternation.Neither treatment nor genotype affected exploration times. |

| Sung et al. 25 | In vivo animal study (using 3xTg-AD mice and wild type mice) and in vitro study (using day 18–19 Sprague-Dawley embryonic cortical and hippocampal neurons). | In vivo - Aβ levels - 3xTg-AD mice received W2 50 mg kg–1 or control (10% DMSO) daily for 2 weeks.In vivo – tau phosphorylation - 3xTg-AD mice received W2 50 mg kg–1 or control (10% DMSO) daily for 4 weeks.In vivo – learning and memory – wild type mice received W2 50 mg kg–1 or control (10% DMSO) daily for 4 weeks.In vitro – cells were treated with W2 (1 μ m or 5 μ m), I2 (1 μ m or 5 μ m) or vehicle (10% DMSO) for 24 h. | In vivo – W2 did not change Aβ42 levels but significantly reduced Aβ40 levels compared with controls.In vitro – W2 or I2 significantly reduced Aβ40 (decreased by 20%) in rat neurons. | In vivo – tau phosphorylation at the Thr181 site was specifically and significantly reduced by W2 but was not reduced at Th231 or other serine residues. | 3xTg-AD mice showed an improvement in learning and memory when treated with W2. |

| Vepsäläinen et al. 14 | In vivo animal study (using APP/PS1 mice) and in vitro study (using APP751 overexpressed human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells). | In vivo – Teklad 2016 diet (control); anthocyanin-enriched bilberry (BB) chow (treatment); anthocyanin-enriched blackcurrant (BC) chow for 11.5 months.In vitro – 50 μ m menadione with or without quercetin (0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 2, 5, 10 μ m), myricetin (0.5, 2, 5, 10, 20 μ m) or 86% anthocyanin-rich extracts (4, 8, 16, 31, 62 µg ml–1) for 24 h. | In vivo – APP/PS1 mice fed the BB diet showed ∼30% decrease in soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels.In vitro – quercetin decreased APP maturation at 10μM. | In vivo - Anthocyanin rich diet had no effect on the phosphorylation of tau. | In vivo – A small improvement in spatial working memory was noted (P = 0.41) in BC extract vs. control but was not significant. |

| Wang et al. 13 | In vivo animal study (using E129 mice). | Mice received 4.8 n m Aβ42 or vehicle (10% DMSO) daily for 1 week followed by 10 mg kg–1 PTI-125 daily for 2 weeks. | Aβ42 mice treated with PTI-125 showed decreased amyloid deposits on immunostained Aβ42 aggregates. | Aβ42 mice treated with PTI-125 showed suppression of phosphorylation of tau at all three phosphorylation sites. | – |

| Xue et al. 29 | In vivo animal study (using APPswe/PS1dE9 and wild type mice) and in vitro study (using SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells). | APPswe/PS1dE9 and wild type mice received infusions of 5μl XD4 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or PBS as a vehicle control weekly for 4 weeks.SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were treated with Aβ42 incubated with XD4 for 1 h at ratios of Aβ : XD4 = 1 : 1, Aβ : XD4 = 1 : 10 and Aβ alone in concentrations of 2 μ m and 5 μ m and then incubated for 2 days. | In vivo – hippocampal and cortical amyloid plaques were fewer in XD4 treated APPswe/PS1dE9 mice compared with controls.In vitro – SH-SY5Y cells showed reduced cytotoxicity when treated with XD4, less toxicity was noted when cells were pre-incubated with Aβ42. | – | XD4 treated APPswe/PS1dE9 mice showed improvements in escape latency compared with control mice. |

| Yang et al. 20 | In vivo animal study (using C57BL/6 mice). | Five groups: vehicle solvent - 0.35% acetonitrile + 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (control); Aβ1-40 – 400 pmol in 5 µl/mouse (control);Aβ1-40 - 400pmol in 5 µl/mouse + melatonin 10 mg kg–1 (treatment);Aβ1-40 – 400 pmol in 5 µl/mouse + EGT 0.5mg 10 ml–1 kg–1 (treatment); Aβ1-40 – 400 pmol in 5 µl/mouse + EGT 2.0 mg 10 ml kg–1 (treatment). | Mice from the melatonin and EGT treatment groups had less Aβ accumulation in their hippocampus compared with the Aβ1-40 group. High and low dose EGT reduced the area of Aβ plaque significantly (P < 0.05).Between the high and low dose EGT groups there was no significant differences in outcome. | – | – |

Methodological quality summary

The results for the risk of bias assessment are summarized in Table3.

Table 3.

Summary of author’s risk of bias decisions

Key: Low Risk of Bias  Unclear Risk of Bias

Unclear Risk of Bias  High Risk of bias

High Risk of bias

Effects of interventions

The agents studied in the selected trials were classified based on their putative mechanism of action and their effects on AD pathology into the following groups, anti-amyloidogenic agents, neuro-protective agents, GSK-3β inhibitors and miscellaneous agents.

Anti-amyloidogenic agents

All of the anti-amyloidogenic agents chosen for inclusion into this review showed improvement in amyloid precursor protein processing, with three studies demonstrating a significant reduction in Aβ levels (P < 0.05) 9–11. Five of the studies also provided evidence of reduced tau phosphorylation despite targeting the amyloid pathology associated with AD 9–13, with the study conducted by Wang et al. 13 demonstrating that PTI-125 suppressed the phosphorylation of tau at all three of the tau phosphorylation sites. Vepsäläinen et al. 14 examined the effects of the anthocyanin rich diet on the levels of tau phosphorylation but they observed no changes. Cognition was improved, but not necessarily statistically significantly, following the dose and duration of the given investigations 10,12,14,15.

Neuro-protective agents

Cognition was improved significantly in the three studies that measured this outcome, P = 0.03, P < 0.001, P = 0.0001, as shown by Barron et al. 16, Lo et al. 17 and O’Hare et al. 18, respectively. Aβ pathology was improved significantly in all studies with the exception of Lo et al. 17 who experience no change following intervention. Ramalho et al. 19 reported that TUDCA significantly prevented Aβ-induced cell death (P < 0.05) and Yang et al. 20 reported a significant decrease in Aβ plaque area following intervention (P < 0.05).

GSK-3β inhibitors

All of the outcomes measured in the studies showed an improvement, whether this be in Aβ pathology, tau pathology or in cognition. Durairajan et al. 21 showed a significant improvement in the area occupied by Aβ deposits (P < 0.001) showing potential for disease modification. A significant improvement (P < 0.01) was seen in the levels of tau phosphorylation in the study of GAO by Farr et al. 22. A significant improvement in cognition was also seen in two studies 21,22.

Miscellaneous agents

Of the seven studies that investigated the effects of their intervention on Aβ pathology, all observed changes in the levels of Aβ but only two reported a statistically significant difference in their treatment groups vs. controls 23,24. Sung et al. 25 also reported a significant change in Aβ pathology but only in terms of Aβ1-40 and not the toxic species Aβ1-42. Tau phosphorylation was significantly decreased in three studies 25–27, with Sung et al. 25 reporting that it was significantly reduced specifically at the Thr181 site of tau phosphorylation. Corona et al. 23 reported that their intervention had no effect on the phosphorylation of tau and similarly, Nikkel et al. 28 stated that their intervention did not affect tau when it was given alone. The majority of the studies that tested their subjects for changes in cognition reported a significant change in treatment groups when compared with control groups. Two of these produced non-significant changes in cognition 24,29 and Sierksma et al. 30 reported that their intervention, GEBR-7b, had no effect on cognition.

Discussion

Anti-amyloidogenics, neuro-protectants, GSK-3β inhibitors and the various miscellaneous agents chosen for inclusion in this systematic review, generally, significantly improved the Aβ pathology, tau pathology and cognitive effects associated with AD. Many different drug targets were established in the trials through the use of agents to target the various pathological manifestations implicated in AD.

Summary of evidence

Altering tau pathology

Tau hyperphosphorylation has significant effects on neuronal degeneration and cell death as it affects the cytoskeleton due to dissociation of the tau protein from microtubules. The prevention of hyperphosphorylation has the potential to prevent neurofibrillary tangles associated with AD pathology and also slow/prevent damage to neurons that is caused by dissociation of hyperphosphorylated tau.

Many of the studies selected for this review report that they have observed a significant reduction in tau phosphorylation during the study of their novel agent. It is important to note here that although results such as these seem both highly beneficial and interesting, the AD model used must be taken into account, as not all AD animal models actually possess traits that would develop into neurofibrillary tangles from excessive tau hyperphosphorylation. For example, Shytle et al. 11 used the Tg2576 AD model which displays no evidence of neurofibrillary tangles yet it was reported in their study that their intervention, HSS-888, decreased the soluble fractions of phosphorylated tau in the examined brain homogenates. It must be considered that these are two different outcomes with potentially different clinical outcomes. There is no evidence here that there is an effect on neurofibrillary tangles, due to a reduction in tau hyperphosphorylation, as the Tg2576 mice do not exhibit this trait.

Altering Aβ pathology

Reduction in Aβ burden

Reducing the amount of toxic amyloid beta peptides present in the brain is thought to be a key method of reducing AD pathology and preventing the Aβ associated cellular damage. Many studies conducted in animal AD models have shown a reduction in Aβ peptide burden in the brains of animals following intervention, which has the potential to prevent plaque formation.

The results from the three studies specifically investigating a reduction in Aβ1-40 and/or Aβ1-42 levels in animal AD models 9,14,31, were very promising but it has to be remembered that a mouse model of AD is still very different from AD in humans. The clearance rate of amyloid-β peptides in mice is at least five times greater than that of the human brain and how the rate of degradation compares between a mouse brain and a human brain is still unknown. Therefore the applicability of these results to progression into clinical trials has to be questioned 32.

Prevention of Aβ accumulation

Perhaps one of the most promising aspects of AD treatment is the prospect of prevention of Aβ peptide accumulation. If the disease could be prevented by treatment before the disease has progressed, patients at high risk for the disease could be identified and given prophylactic treatment to prevent the disease establishing or progressing any further. Although the small amount of evidence for prevention was promising, it would be difficult to transfer this into practical use as the risk factors for AD and the potential of these risk factors to cause AD is still not fully understood. Therefore, it would be difficult to know when to initiate such a treatment to gain its full effects. This would also be something that would be difficult to study in human subjects in anything other than a retrospective study. It would also be difficult to identify patients at risk of AD and then determine whether the onset/lack of onset of AD was due to the treatment.

Cognitive effects

Reporting the changes in cognition in animal studies relies on the evidence of specialist tasks that test spatial learning, spatial working memory and short/long term memory. Anxiety levels are often also reported, as anxiety can be one of the early signs associated with AD. Obviously, it is difficult to compare the results of such tests to the cognition of humans. However studies such as those discussed highlight the potential benefits of the novel agents on cognition. Generally, cognition was improved by many of the agents for the emerging targets. Of the 19 studies that investigated the effects of their agent on cognition, only two reported that there were no changes in cognition 23,30, and 10 reported significant changes demonstrating an improvement across all drug classes 12,16–18,21,22,27,33–35.

Many of the studies included in this systematic review used the Morris water maze test, a specially designed test aimed to study spatial learning and memory of the subject, as the animal must find the platform without any sensory clues. There are no olfactory or sensory stimuli to aid identification of where the hidden platform resides. The use of the Morris water maze test can examine learning and memory with more reliable results than the use of the T-maze test. Spontaneous alternation in the T-maze is a 50 : 50 chance. Therefore it has a greater potential to be due to chance rather than due to effects on spatial working memory 40. However, the Morris water maze test was designed for use in rats as they are naturally accustomed to water, but many studies use mice as their test subjects which therefore has the potential to confound results. These factors must be taken into account when establishing the reliability of studies.

Limitations

There are limitations in this review, the main limitation being the lack of information disclosed regarding bias. The risk of bias was determined to be high in many studies, which indicated there was a potential for biased reporting as all of the information, required to clearly state all possible factors of bias, could not be established. Simple factors could have been specified to reduce the risk of bias, such as the type of food used and how this differed between treatment and control groups.

The results of this study are also limited by the fact that all of the studies were conducted either in vitro or in vivo using animals as test subjects. This prevents the results from being easily transferrable to human studies. Obviously this was an expected limitation as a drug target would not be classed as an emerging target if it was established enough to be being tested in human subjects.

The results reported in the trials were often significant in terms of the studies’ particular outcomes. However their clinical significance remains unknown.

Conclusion

It is clear that there are many potential drug targets for AD that are still yet to be fully explored as many of the novel agents discussed are showing great potential for reducing the pathological and cognitive effects associated with AD. More good quality animal studies, with a significantly lower risk of bias, would be needed to establish the true extent of the effects of each agent before considering investigation in human subjects. It would also be beneficial to increase the duration of study, because despite AD being a chronic progressive disease, many of the in vivo animal studies were conducted over a short period of time therefore preventing the full extent of the agents’ effects to be identified. Studies involving human subjects would pose an interesting progression to the current research, to establish whether the significant effects on Aβ/tau pathology and cognition could be repeated.

Competing Interest

Both authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Sources of funding

No funding was provided for this review.

References

- The PRISMA Group. Transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 2009. Available at http://www.prisma-statement.org/statement.htm (last accessed 3 April 2014)

- Alzheimer’s Society. Dementia 2013 Infographic. 2014. Available at http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/infographic (last accessed 21 February 2014)

- Li SY, Wang XB, Kong LY. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of imine resveratrol derivatives as multi-targeted agents against Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;71:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila J, Lucas JJ, Perez M, Hernandez F. Role of tau protein in both physiological and pathological conditions. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:361–84. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez F. Gomez de Barreda E, Fuster-Matanzo A. GSK3: A possible link between beta amyloid peptide and tau protein. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:322–5. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang IJ, Jeon YE, Yin XF, Nam JS, You SG, Hong MS, Jang BJ, Kim MJ. Butanol extract of Ecklonia cava prevents production and aggregation of beta-amyloid, and reduces beta-amyloid mediated neuronal death. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2011. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease . Available at http://publications.nice.org.uk/donepezil-galantamine-rivastigmine-and-memantine-for-the-treatment-of-alzheimers-disease-ta217 (last accessed 4 April 2014)

- Krauth D, Woodruff T, Bero L. A Systematic Review of Quality Assessment Tools for Published Animal Studies, 2012. [Online Poster] Available at http://2012.colloquium.cochrane.org/sites/2012.colloquium.cochrane.org/files/uploads/posters/126.pdf (last accessed 13 March 2014)

- Geekiyanage H, Upadhye A, Chan C. Inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase reduce Aβ and tau hyperphosphorylation in a murine model: a safe therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2037–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inestrosa NC, Tapia-Rojas C, Griffith TN, Carvajal FJ, Benito MJ, Rivera-Dictter A, Alvarez AR, Serrano FG, Hancke JL, Burgos PV, Parodi J, Varela-Nallar L. Tetrahydrohyperforin prevents cognitive deficit, Aβ deposition, tau phosphorylation and syntaptotoxicity in the APPswe/PSEN1ΔE9 model of Alzheimer’s disease: a possible effect on APP processing. Transl Psychiatry. 2011;1:e20. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.19. Published online 12 Jul 2011. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shytle RD, Tan J, Bickford PC, Rezai-zadeh K, Hou L, Zeng J, Sanberg PR, Sanberg CD, Alberte RS, Fink RC, Roschek B., Jr Optimized Turmeric Extract Reduces β-Amyloid and Phosphorylated Tau Protein Burden in Alzheimer’s Transgenic Mice. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:500–6. doi: 10.2174/156720512800492459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Hoppe JB, Coradini K, Frozza RL, Oliveira CM, Meneghetti AB, Bernardi A, Simoes Pires E, Beck RCR, Salbego CG. Free and nanoencapsulated curcumin suppress β-amyloid-induced cognitive impairments in rats: Involvement of BDNF and Akt/GSK-3β signalling pathway. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;106:134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Bakshi K, Frankfurt M, Stucky A, Goberdhan M, Shah SM, Burns LH. Reducing Amyloid-Related Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis by a Small Molecule Targeting Filamen A. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9773–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0354-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vepsäläinen S, Koivisto H, Pekkarinen E, Mäkinen P, Dobson G, McDougall GJ, Stewart D, Haapasalo A, Karjalainen RO, Tanila H, Hiltunen M. Anthocyanin-enriches bilberry and blackcurrant extracts modulate amyloid precursor protein processing and alleviate behavioural abnormalities in the APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:360–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camboni M, Wang CM, Miranda C, Yoon JH, Xu R, Zygmunt D, Kaspar BK, Martin PT. Active and passive immunization strategies based on the SDPM1 peptide demonstrate pre-clinical efficacy in the APPswePSEN1dE9 mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;62:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron AM, Garcia-Segura LM, Caruso D, Jayaraman A, Lee JW, Melcangi RC, Pike CJ. Ligand for translocator protein reverses pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8891–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1350-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo AC, Tesseur I, Scopes DIC, Nerou E, Callaerts-Vegh Z, Vermaercke B, Treherne JM, De Strooper B, D’Hooge R. Dose-dependent improvements in learning and memory deficits in APPPS1-21 transgenic mice treated with the orally active Aβ toxicity inhibitor SEN1500. Neuropharmacology. 2013;75:458–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare E, Scopes DIC, Kim EM, Palmer P, Jones M, Whyment AD, Spanswick D, Amijee H, Nerou E, McMahon B, Treherne JM, Jeggo R. Orally bioavailable small molecule drug protects memory in Alzheimer’s disease models. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho RM, Nunes AF, Dias RB, Amaral JD, Lo AC, D’Hooge R, Sebastiao AM, Rodrigues CMP. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid suppresses amyloid β-induced synaptic toxicity in vitro and in APP/PS1 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:551–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang NC, Lin HC, Wu JH, Ou HC, Chai YC, Tseng CY, Liao JW, Song TY. Ergothioneine protects against neuronal injury induced by β-amyloid in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:3902–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durairajan SSK, Liu LF, Lu JH, Chen LL, Yuan Q, Chung SK, Huang L, Li XS, Huang JD, Li M. Berberine ameliorates β-amyloid pathology, gliosis, and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2903–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr SA, Ripley JL, Sultana R, Zhang Z, Niehoff ML, Platt TL, Murphy MP, Morley JE, Kumar V, Butterfield DA. Antisense oligonucleotide against GSK-3β in brain of SAMP8 mice improves learning and memory and decreases oxidative stress: Involvement of transcription factor Nrf2 and implications for Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;67:387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona C, Frazzini V, Silvestri E, Lattanzio R, La Sorda R, Piantelli M, Canzoniero LMT, Ciavardelli D, Rizzarelli E, Sensi SL. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Carnosine on Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Amyloid Pathology and Cognitive Deficits in 3xTg-AD Mice. Plos One. 2011;6:e17971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017971. Published online 15 Mar 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Gonzalez R, Pascual C, Antequera D, Bolos M, Redondo M, Perez DI, Perez-Grijalba V, Krzyzanowska A, Sarasa M, Gil C, Ferrer I, Martinez A, Carro E. Phosphodiesterase 7 inhibitor reduced cognitive impairment and pathological hallmarks in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2133–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung YM, Lee T, Yoon H, DiBattista AM, Song JM, Sohn Y, Moffat EI, Turner RS, Jung M, Kim J, Hoe HS. Mercaptoacetamide-based class II HDAC inhibitor lowers Aβ levels and improves learning and memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2013;239:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner RS, Markosyan S, Nikkel AL, Brioni JD. In vivo histamine H3 receptor antagonism activates cellular signalling suggestive of symptomatic and disease modifying efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwaya Y, Bergman C, Lee JH, Wan R, King MT, Mughal MR, Okun E, Clarke K, Mattson MP, Veech RL. A ketone ester diet exhibits anxiolytic and cognition-sparing properties and lessens amyloid and tau pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1530–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkel AL, Martino B, Markoysan S, Brederson JD, Medeiros R, Moeller A, Bitner RS. The novel calpain inhibitors A-705253 prevents stress-induced tau hyperphosphorylation in vitro and in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:606–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D, Zhao M, Wang YJ, Wang L, Yang Y, Wang SW, Zhang R, Zhao Y, Liu R. A multifunctional peptide rescues memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice by inhibiting Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity and increasing microglial phagocytosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:701–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierksma ASR, van den Hove DLA, Pfau F, Philippens M, Bruno O, Fedele E, Ricciarelli R, Steinbusch HWM, Vanmierlo T, Prickaerts J. Improvement of spatial memory function in APPswe/PS1dE9 mice after chronic inhibition of phosphodiesterase type 4D. Neuropharmacology. 2014;77:120–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMattos RB, Lu J, Tang Y, Racke MM, DeLong CA, Tzaferis JA, Hole JT, Forster BM, McDonnell PC, Liu F, Kinley RD, Jordan WH, Hutton ML. A plaque-specific antibody clears existing β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neuron. 2012;76:908–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qosa H, Abuasal BS, Romero IA, Weksler B, Couraud PO, Keller JN, Kaddoumi A. Differences in amyloid-β clearance across mouse and human blood–brain barrier models: Kinetic analysis and mechanistic modelling. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:668–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbemenyah HY, Agis-Balboa RC, Burkhardt S, Delalle I, Fischer A. Insulin growth factor binding protein 7 is a novel target to treat dementia. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;62:135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioanca O, Hritcu L, Mihasan M, Hancianu M. Cognitive enhancing and antioxidant activities of inhaled coriander volatile oil in amyloid β(1-42) rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Physiol Behav. 2013;120:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani D, Bitto A, Galantucci M, Zaffe D, Ottani A, Irrera N, Neri L, Cavallini GM, Altavilla D, Botticelli AR, Squadrito F, Guarini S. Melanocortins protect against progression of Alzheimer’s disease in triple-transgenic mice by targeting multiple pathophysiological pathways. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:538–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, An FM, Yin L, Liu AR, Yin DK, Yao WB, Gao XD. Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects hippocampal neurons against advanced glycation end product-induced tau hyperphosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2014;256:137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang IJ, Jan BG, In S, Choi B, Kim M, Kim MJ. Phlorotannin-rich Ecklonia cava reduces the production of beta-amyloid by modulating alpha- and gamma-secretase expression and activity. Neurotoxicology. 2013;34:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedowicz DM, Studzinski CM, Weidner AM, Platt TL, Kingry KN, Beckett TL, Bruce-Keller AJ, Keller JN, Murphy MP. Leptin regulates amyloid β production via the γ-secretase complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1832;2013:439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Zhang J, Qin M. Protective effect of cyaniding 3-O-glucoside on beta-amyloid peptide-induced cognitive impairment in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2013;534:285–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Meth. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]