Abstract

Human hearing differs from that of chimpanzees and most other anthropoids in maintaining a relatively high sensitivity from 2 kHz up to 4 kHz, a region that contains relevant acoustic information in spoken language. Knowledge of the auditory capacities in human fossil ancestors could greatly enhance the understanding of when this human pattern emerged during the course of our evolutionary history. Here we use a comprehensive physical model to analyze the influence of skeletal structures on the acoustic filtering of the outer and middle ears in five fossil human specimens from the Middle Pleistocene site of the Sima de los Huesos in the Sierra de Atapuerca of Spain. Our results show that the skeletal anatomy in these hominids is compatible with a human-like pattern of sound power transmission through the outer and middle ear at frequencies up to 5 kHz, suggesting that they already had auditory capacities similar to those of living humans in this frequency range.

Knowledge about the sensory capabilities of past life forms could greatly enhance our understanding of the adaptations and lifeways in extinct organisms. Audition is the most readily accessible in fossils because it is based primarily in physical properties that can be approached through their skeletal structures (1). Recently, the possibility to analyze auditory capacities in fossil species has been highlighted as one of the major challenges in modern vertebrate paleontology, particularly since the advent of computed tomography (CT)-based analyses (2).

The recent publication of a detailed comparison of the human and chimpanzee genomes has highlighted several genes involved with hearing that appear to have undergone adaptive evolutionary changes in the human lineage (3). The authors have suggested that these changes could be related with the acquisition of hearing acuity necessary for understanding spoken language, and they emphasize the importance of further research into hearing differences between humans and chimpanzees (3). At least one of the human genes mentioned as having undergone adaptive evolutionary change (EYA1) is related to the development of the outer and middle ear (4, 5). These results are compatible with the known differences in the anatomical structures of the outer and middle ear in chimpanzees and ourselves (6, 7).

As might be expected from these genetic and anatomical data, the empirical studies of chimpanzee hearing capabilities also show clear differences with human hearing. Chimpanzee audiograms (8, 9) show a W-shaped pattern characterized by two peaks of high sensitivity at ≈1 kHz and 8 kHz, respectively, and a relative loss of sensitivity in the midrange frequencies (between 2 and 4 kHz). Of course, this relative loss does not mean that chimpanzees cannot hear in the midrange frequencies, but rather that they are adapted to hear best at ≈1 kHz and 8 kHz. It is interesting to note that the species-specific pant-hoots regularly emitted by wild chimpanzees to communicate with conspecifics over long distances concentrate the acoustic information at ≈1 kHz (10).

At the same time, although human audiograms also show a high sensitivity at ≈1 kHz, they differ from chimpanzees in lacking the marked relative loss in sensitivity between 2 and 4 kHz, maintaining a relatively high sensitivity within this frequency range (9, 11–13).

In this context, knowledge of the auditory capacities in human fossil ancestors could greatly enhance the understanding of when this human pattern emerged during the course of our evolutionary history. A few prior studies have approached this question in fossil hominids, but they should be considered with caution because they are based on simplified physical models relying on only a few anatomical variables (6, 14).

To accurately approach the auditory capacities in fossil specimens it is necessary to consider the acoustic and mechanical properties of each component of the outer and middle ears and the way in which they interact (15–17). Although some of these anatomical components are related to soft tissues (e.g., ligaments) that do not preserve in the fossil record, the remaining skeletal structures can provide relevant information about the auditory capacities in fossil specimens.

Here we have applied a comprehensive physical model, implemented with its analog electrical circuit, to evaluate the effects of the skeletal anatomy on the acoustic filtering and sound power transmission through the outer and middle ears in five individuals from the Middle Pleistocene site of the Sima de los Huesos (SH) in the Sierra de Atapuerca of Spain.

Materials and Methods

Materials. The SH human fossils have a firm minimum radiometric age limit of 350 thousand years (18). They have been argued to be phylogenetically close to the Neandertals and are attributed to the species Homo heidelbergensis (19–21). Among the SH human fossils, there are two adult specimens (Cranium 5 and the isolated left temporal bone AT-84) and one juvenile individual (another isolated left temporal bone labeled AT-421) in which the external and middle ears are exposed, making it possible to directly measure many of the anatomical variables necessary for this study. We have also measured two additional juvenile isolated temporal bones (AT-1907, right, and AT-4103, left) in which the external and middle ears are not exposed. To measure the necessary variables in these individuals, we have relied on their 3D CT reconstructions, using mimics 8.0 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). The accuracy of the CT-based measurements in these individuals is guaranteed by the fact that the measurements taken on a similar 3D CT reconstruction of Cranium 5 were not significantly different from the comparable direct measurements taken on this same specimen (Table 1). Given this agreement, we have relied on all of the values obtained in the 3D CT reconstructions for Cranium 5, AT-1907, and AT-4103. Further, to complete the measurements related with the cavities of the middle ear and mastoid in AT-84 and AT-421, we have used the average value of Cranium 5, AT-1907, and AT-4103 (Table 2).

Table 1. Original measurements of the outer and middle ears in the SH and Pan individuals.

| Cranium 5

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical variables | CT | Direct | AT-84 | AT-421 | AT-1907 | AT-4103 | Pan |

| VMA, cm3 | 2.15 | 3.68 | 5.90 | 4.18 | |||

| VAD, cm3 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.095 | |||

| VMEC, cm3 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.26 | |||

| LAD, mm | 8.6 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.5 | |||

| RAD1, mm | 4.4 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 1.8 | |||

| RAD2, mm | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 1.7 | |||

| RTM1, mm | 5.8 | 5.75 | 5.9 | 5.75* | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.95 |

| RTM2, mm | 4.55 | 4.5 | 4.55 | 4.5† | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| LEAC, mm | 16.4 | 17.4 | 17 | 14.4 | 16.0 | 17.0 | 22.8 |

| REAC1, mm | 3.7 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.1 |

| REAC2, mm | 2.1 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 4.0‡ | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.0 |

| LI, mm | 4.2 | 3.3 | |||||

| LM, mm | 5.2 | 5.5 | |||||

| MI, mg | 28.7§ | 23.0 | |||||

| MM, mg | 24.0§ | 23.8 | |||||

| AOW, mm2 | 3.02 | 3.98 | 3.12 | ||||

| AFP, mm2 | 2.77 | ||||||

VMA, VAD, VMEC, LAD, LEAC, LM, LI, and AFP are as in Fig. 1. RAD1, half of the measured greater diameter of the entrance to the aditus ad antrum from the middle ear cavity (dotted line 2, Fig. 1A); RAD2, half of the measured lesser diameter (perpendicular to RAD1) of the entrance to the aditus ad antrum from the middle ear cavity; RTM1, half of the measured greater diameter of the tympanic membrane measured in the tympanic groove (sulcus tympanicus); RTM2, half of the measured lesser diameter (perpendicular to RTM1) of the tympanic membrane measured in the tympanic groove; REAC1, half of the measured superoinferior diameter of the external auditory canal at the level of the superior point of the tympanic groove (dotted line 4, Fig. 1A); REAC2, half of the measured anteroposterior diameter (perpendicular to REAC1) of the external auditory canal at the level of the superior point of the tympanic groove; MI, mass of the incus; MM, mass of the malleus; AOW, area of the oval window.

The value of RTM1 in AT-421 was reconstructed from the preserved portion of the tympanic ring

The value of RTM2 in AT-421 was estimated from the values in the other Atapuerca specimens

Although AT-421 lacks the tympanic portion of the EAC, the preserved squamous portion represents half of the original EAC, and the REAC2 can be reliably measured directly

We are confident in using the Atapuerca values because the measured masses and general dimensions of the malleus and incus in the Atapuerca hominids are similar to the published modern human masses (22, 23) and the dimensions measured by us in a multiracial modern human sample (see supporting information)

Table 2. Values of the outer and middle ear variables used in the physical model.

| Anatomical variables | Cranium 5 (CT) | AT-84 | AT-421 | AT-1907 | AT-4103 | Pan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VMA + VAD, mm3 | 2.40 | 4.10 | 4.10 | 3.85 | 6.05 | 4.27 |

| VMEC, mm3 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.26 |

| LAD, mm | 8.6 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.5 |

| RAD, mm | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 1.8 |

| ATM, mm2 | 82.9 | 84.3 | 82.2 | 74.8 | 76.8 | 76.2 |

| LEAC complete, mm | 24.6 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 24.0 | 25.5 | 34.2 |

| AEAC, mm2 | 26.4 | 59.4 | 51.5 | 30.2 | 31.2 | 20.4 |

| LM/LI, mm | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| MM + M1, mg | 52.7 | 52.7 | 52.7 | 52.7 | 52.7 | 46.8 |

| AFP, mm2 | 2.8 | 3.6* | 2.8* | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.4† |

Abbreviations are as in Fig. 1 and Table 1. RAD, radius of the entrance to the aditus ad antrum, calculated as the average of RAD1 and RAD2 (Table 1); ATM, area of the tympanic membrane calculated as an ellipse from RTM1 and RTM2 (Table 1); LEAC complete, calculated by multiplying the value of LEAC (Table 1) by 1.5, to include the cartilaginous portion of the external ear (6, 24–26); AEAC, cross-sectional area of the external auditory canal calculated as a circle from REAC1 and REAC2 (Table 1). For the values related with the middle ear cavities and mastoid air cells in AT-84 and AT-421, we have used the average value of the other three SH specimens. We have used the value from the ear ossicles extracted from AT-1907 for all the SH individuals. We have use the directly measured value of the stapes footplate in Cranium 5 for both AT-1907 and AT-4103.

The footplate area in AT-84 and AT-421 was estimated as 90% of the area of the oval window (AOW in Table 1), as suggested by measurements from Cranium 5 and ref. 14

Ref. 6

In the SH collection, the malleus (AT-3746) and incus (AT-3747) are preserved in the juvenile right isolated temporal bone AT-1907, allowing us to measure the functional lengths of these bones in a single individual. Cranium 5 preserves its left stapes (AT-667). For AT-84 and AT-421, we have estimated the footplate area from their exposed oval windows (Table 2). Because the area of the oval windows cannot be measured in the 3D CT reconstructions, we have used the directly measured value of the footplate area in Cranium 5 for the AT-1907 and AT-4103 individuals (Table 2).

For some specific aspects of the study, we have also measured some variables in the temporal bones from a Spanish Medieval sample (n = 30) and in the ear ossicles in a modern multiracial sample housed in Seneca Falls, New York (n = 41).

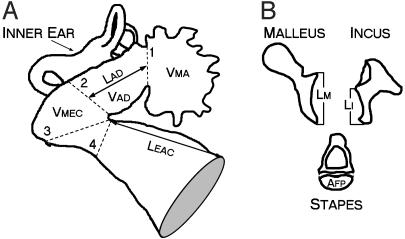

The definitions and values of the variables used in the model in this study are presented in Fig. 1 and Tables 2 and 3.

Fig. 1.

Measurements of the middle and external ear (A) and ear ossicles (B). A and B are not drawn to the same scale. A is based on the CT images of Cranium 5. VMA, volume of the mastoid antrum and connected mastoid air cells, measured from its limit with the aditus ad antrum (dotted line 1); VAD, volume of the aditus ad antrum, measured from its limit with the middle ear (dotted line 2) to its limit with the mastoid antrum (dotted line 1); VMEC, volume of the middle ear cavity measured from its limit with the aditus ad antrum (dotted line 2) to the edge of the tympanic groove (dotted line 3); LAD, length of the aditus ad antrum, measured as the mean distance from its limit with the middle ear cavity to the entrance to the mastoid antrum; LEAC, length of the external auditory canal, measured from the superior point of the tympanic groove to the spina suprameatum. Dotted line 4 marks the level at which the cross-sectional area of the external auditory canal (AEAC) was measured. B is based on the profiles of the malleus and incus from the temporal bone AT-1907 and the stapes from Cranium 5. LM, functional length of the malleus, measured as the maximum length from the superior border of the short process to the inferior-most tip of the manubrium; LI, functional length of the incus measured from the lateral-most point along the articular facet to the lowest point along the long crus; AFP, measured area of the footplate of the stapes.

Table 3. Definition of the electrical parameters, their related anatomical variables, the source of the value used, and the sensitivity analysis for frequencies above 2 kHz in the model.

| Related anatomical variables

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical parameters | Definition | Value used | Sensitivity (≥2 kHz) | |

| External ear | ||||

| Two-port network that models the concha horn | Concha length | Rosowski (17) | High (A) | |

| Cross-sectional area of wide end | Rosowski (17) | High (A) | ||

| Two-port network that models the ear canal tube | Cross-sectional area of narrow end | Measured as AEAC | High (A) | |

| Ear canal length | Measured as LEAC complete | High (A) | ||

| Cross-sectional area of the ear canal | Measured as AEAC | High (A) | ||

| Middle ear | ||||

| Middle ear cavity | CTC | Volume of the middle ear cavity | Measured as VMEC | Low (A) |

| CMC | Volume of the aditus and mastoid air spaces | Measured as VAD + VMA | Low (A) | |

| RA | Surface area of the aditus and mastoid air spaces | Rosowski (17) | Low (E) | |

| LA | Length and radius of the aditus | Measured as LAD and RAD | Low (E) | |

| Tympanic membrane and mallear attachment | ATM | Area of the tympanic membrane | Measured as ATM | High (A) |

| LT1 | Mass of the tympanic membrane | Estimated from ATM* | High (A) | |

| CT | Structural properties of the tympanic membrane and mallear attachment | Rosowski (17) | Low (E) | |

| RT | Low (E) | |||

| LT | Low (E) | |||

| CT2 | Low (E) | |||

| RT2 | Medium (E) | |||

| CTS | High (E) | |||

| RTS | Medium (E) | |||

| Malleus, incus, ligaments and stapes | II:IM | Functional lengths of the incus and malleus | Measured as LI/LM | High (A) |

| LMIM | Masses of the incus and malleus | Measured as MI + MM | Medium (A) | |

| RMIM | Non-articular surface area of the malleus and incus | Rosowski (17) | Low (E) | |

| CMIM | Structural properties of the malleus and incus | Rosowski (17) | Low (E) | |

| LSM | Mass of the stapes | Rosowski (17) | Low (A) | |

| RJM | Structural properties of the ossicular joints | Rosowski (17) | Low (E) | |

| CJM | Low (E) | |||

| AFP | Area of the stapes footplate | Measured as AFP | Medium (A) | |

| Inner ear | ||||

| Annular ligament | CAL | Structural properties of the annular ligament | Rosowski (17) | † |

| RAL | High (E) | |||

| Cochlea | ZC | Structural properties of the cochlea | Aibara et al. (27) | High (E) |

All definitions and abbreviations of the electrical parameters follow Rosowski (17), except ZC (cochlear input impedance), which follows Aibara et al. (27). Anatomical variables are as in Fig. 1 and Table 2. Sensitivity is measured as the difference between the value for sound power at the entrance to the cochlea (in dB), using the values provided by Rosowski (17) and Aibara et al. (27), and that obtained by increasing and decreasing the individual anatomical variable (A) or electrical parameter (E) by 50% from the respected values reported by Rosowski (17) and Aibara et al. (27). Sensitivity has been classified into three broad groupings: low (≤1 dB difference), medium (>1 to ≤3 dB difference), and high (>3 dB difference).

The mass of the tympanic membrane was estimated based on its area, extrapolating from the values for modern humans provided by Rosowski (17)

The value provided for this variable in Rosowski (17) is infinite and is not included in the sensitivity analysis

The Physical Model. The use of electrical circuits to model sound power transmission through the outer and middle ear is a common practice in auditory research (16, 17, 28–32). Here we have relied on a slightly modified version of the model published by Rosowski (17), to estimate the sound power transmission through the outer and middle ears (see supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site).

The modification we have introduced into the model refers to the cochlear input impedance (Zc), which has been directly measured for the first time in 11 human cadaver ears by Aibara et al. (27), who found a flat, resistive cochlear input impedance with an average value of 21.1 GΩ from 0.1–5.0 kHz. Because our study is focused on the frequency range from 2 to 4 kHz, we have used this empirical value for the cochlear input impedance, rather than the value provided in the original model (17).

To ensure the reliability of our model, we have compared the theoretical middle ear pressure gain (GME) we have obtained for modern humans (see supporting information) with those measured experimentally (27, 33), finding no significant differences. Specifically, in the critical region of 4 kHz, our value of 15.04 dB for GME is intermediate between those found for the same frequency: 12 dB (27) and 18 dB (33).

The electrical parameters used in the model are associated with anatomical structures of the ear. Some of these parameters are related with skeletal structures accessible in fossils, whereas others are related with soft tissues that are not preserved in fossil specimens. Table 3 shows the relationship between the electrical parameters and the anatomical structures, together with an analysis of the sensitivity of the model above 2 kHz to each variable.

We have measured or accurately estimated in the SH specimens all of the 13 skeletal variables included in the model (Table 2). Because the model requires values for all of the variables, the respective value for modern humans (17, 27) has been used for the remaining 17 soft-tissue-related variables that cannot be measured in fossil specimens (Table 3). It is important to note that only seven of these have an appreciable effect on the model results above 2 kHz (labeled as medium and high in Table 3).

To evaluate the influence of the skeletal variables on the interspecific difference in the acoustic filtering patterns, we have measured (Tables 1 and 2), through 3D CT reconstruction, the 13 skeletal variables in one chimpanzee individual (Pan troglodytes), and we have modeled it by using the modern human values (17, 27) for the remaining 17 soft-tissue-related variables, as we have done in the SH specimens.

Although our results are not a true audiogram, it is widely recognized that there is a strong correlation between sound power transmission through the outer and middle ear and auditory sensitivity to different frequencies§§ (35–39). Given that the results for sound power transmission in our chimpanzee individual agree with those of published audiograms for this species (see below), it is reasonable to conclude that the skeletal differences between humans and chimpanzees can explain an important part of the interspecific differences in their patterns of acoustic filtering in the outer and middle ear. Therefore, these skeletal morphology can be used to approach the sound power transmission pattern in closely related fossil human species.

Theoretical Variability in Chimpanzees and Modern Humans. To evaluate whether the effects of the intraspecific skeletal variation could result in the chimpanzee and modern human sound power transmission curves overlapping, we have modeled two theoretical extreme individuals: (i) a “human-like” chimpanzee, using values at the extreme of the chimpanzee variability toward those of modern humans, and (ii) a “chimpanzee-like human,” using values at the extreme of the human variation toward those of chimpanzees (see supporting information).

Clearly, when constructing these theoretical chimpanzee and modern human individuals, we have been limited to relying on those skeletal variables whose intra and interspecific variation is known. Nevertheless, because the skeletal variables that are modified all have a relatively strong effect on the model (labeled medium or high in Table 3), we are confident the analysis is useful to evaluate the results.

We should highlight one important implication from the way that the human-like chimpanzee individual was constructed. We have used modern human values for two skeletal variables (AEAC and MI + MM) in which the chimpanzee range of variation is not known (but which seem to have lower values than modern humans) to model the human-like chimpanzee (see supporting information). This use of modern human values has the effect of overestimating the variation of the chimpanzee toward modern humans, making our human-like chimpanzee, in fact, “superhuman-like.”

Results and Discussion

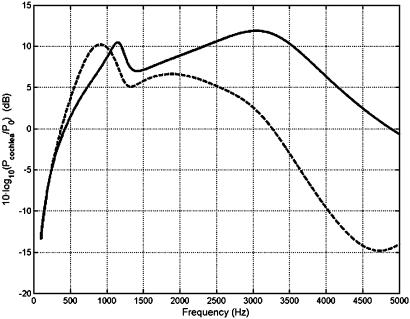

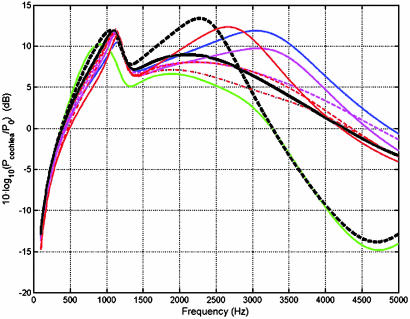

To evaluate the sound power transmission through the outer and middle ears, we have calculated the sound power at the entrance of the cochlea relative to P0 = 10-18 W for an incident plane wave intensity of 10-12 W/m2 (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Sound power (dB) at the entrance to the cochlea relative to P0 = 10-18 W for an incident plane wave intensity of 10-12 W/m2. Results from modern human (solid line) and chimpanzee (dashed line) individuals are shown and were obtained by using the model defined by Rosowski (17) and the cochlear input impedance (Zc) of Aibara et al. (27). Chimpanzee individual is based on the 3D CT reconstruction.

Fig. 3.

Sound power (dB) at the entrance to the cochlea relative to P0 = 10-18 W for an incident plane wave intensity of 10-12 W/m2. All individuals have been modeled by using the model defined by Rosowski (17) and the cochlear input impedance (Zc) of Aibara et al. (27). Solid blue line, modern human; solid green line, chimpanzee 3D CT; solid black line, theoretical chimpanzee-like modern human individual; dashed black line, theoretical human-like chimpanzee individual. solid red line, AT-84; dashed red line, AT-4103; dashed-dotted red line, Cranium 5; solid magenta line, AT-421; dashed magenta line, AT-1907.

Table 4. Values of sound power (dB) at the entrance to the cochlea relative to P = 10-18 W for an incident plane wave intensity of 10-12 W/m2 in the modern human, chimpanzee, and SH individuals at selected frequencies.

| Frequency | Modern human | Chimpanzee-like modern human | Chimpanzee | Human-like chimpanzee | Cranium 5 | AT-84 | AT-421 | AT-1907 | AT-4103 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 kHz | 11.85 | 6.43 | 2.56 | 4.25 | 4.69 | 10.84 | 9.7 | 6.86 | 6.85 |

| 4 kHz | 6.31 | 1.28 | –9.65 | –9.39 | 1.46 | 1.48 | 4.67 | 3.32 | 2.13 |

| 5 kHz | –0.69 | –3.37 | –14.01 | –12.87 | –3.43 | –4.09 | –2.74 | –1.38 | –3.49 |

Our results in modern humans agree with those published by Rosowski (17) that show two peaks in pressure gain at ≈1 and 3 kHz (Fig. 2). At the same time, our results for the chimpanzee agree with those obtained in audiograms (8, 9) in showing a peak in heightened sensitivity ≈1 kHz and a steep loss in sensitivity from 2–4 kHz (Fig. 2). Further, between 2–4 kHz, the human and chimpanzee curves clearly separate, coinciding with that suggested by previous researchers based on audiograms (8, 9), reaching a maximum difference of 16.8 dB at 4,385 Hz. As mentioned above, we interpret this agreement as evidence that the differences in skeletal anatomy can explain much of the interspecific differences in the sound power transmission between these closely related species and, consequently, can also be used to validly infer sound power transmission patterns in fossil hominids.

The sound power transmission curves obtained for the SH hominids, chimpanzee, and modern human individuals and their theoretical ranges of variation are shown in Fig. 3. In addition, Table 4 provides the numerical values for the sound power at the entrance to the cochlea at 3, 4, and 5 kHz. Up to ≈3 kHz, the curve of the human-like chimpanzee overlaps the modern human and SH ranges of variation. Above 3 kHz the chimpanzee curves show a sharp drop in sound power transmission, whereas the modern human curves maintain higher values for sound power transmission. Between 3 and 5 kHz, the distance between the curves that delimit the chimpanzee and human theoretical variation are separated by ≈10 dB, which is especially relevant, given that (as mentioned above) the chimpanzee range of variation toward humans has been overestimated.

At the same time, the sound power transmission curves obtained for the SH hominids are clearly separated from the chimpanzee variation in the distinctive region of ≈4 kHz (from 3 to 5 kHz), falling near or within the modern human variation (Fig. 3 and Table 4).

Thus, our analysis shows that the skeletal anatomy of the outer and middle ear in the SH hominids is compatible with a human-like sound power transmission pattern, clearly different from chimpanzees in the critical region of ≈4 kHz. Because the SH hominids are not on the direct evolutionary line that gave rise to our own species, but form part of the Neandertal evolutionary lineage (19–21), it is conceivable that this condition was already present in the last common ancestor of modern humans and Neandertals. Analysis of Neandertal mtDNA suggests that this last common ancestor probably lived at least 500 thousand years ago (40–42), and it has been argued to be represented among the 800,000-year-old fossils from the TD6 level at the site of Gran Dolina (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain) attributed to the species Homo antecessor (43, 44).

It is reasonable to speculate on the relation between the evolution of human hearing and human spoken language (3). Although much of the acoustic information in spoken language is concentrated in the region up to ≈2.5 kHz (e.g., the first two formant frequencies of the vowels) (45–47), the region between 2 and 4 kHz also contains relevant acoustic information in human speech (47–49). In fact, the frequency range used in telephones reaches up to 4 kHz to ensure the intelligibility of the communication. From this point of view, our results suggest that the skeletal characteristics of the outer and middle ear that support the perception of human spoken language were already present in the SH hominids.

Keeping in mind the direct relation between the auditory patterns in animals and the sounds they are capable of producing (9, 49–53), the immediate implications of our results for the study and reconstruction of the anatomical structures related with speech production in fossil humans have not escaped our notice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Bischoff, G. Cuenca, A. Esquivel, A. Gotherstrom, T. Greiner, J. Lira, J.-A. Linera, G. Manzi, M. Martín-Loeches, A. Muñoz, M.-C. Ortega, J. Pérez-Gil, J.-J. Ruiz, and C. de los Ríos for their valuable help in the elaboration of the present work; and the Atapuerca Research and Excavation Team for their work in the field. The CT scans were taken at the Hospital 12 de Octubre (Cranium 5) and the Hospital Ruber Internacional (Chimpanzee, AT-1907, AT-4103) in Madrid. R.Q. was supported by a Fulbright full grant and a grant from the Fundación Duques de Soria. A.G. was supported by a grant from the Fundación Duques de Soria and the Fundación Atapuerca. C.L. was supported by a grant from the Fundación Atapuerca. J.-L.A. and R.Q. form part of the project Production and Perception of Language in Neandertals (Origines de l'Homme, de Langues et du Language Program, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). The excavations at the Atapuerca sites are funded by the Junta de Castilla y León. This work was supported by Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología of the Government of Spain Project BOS2003-08938-C03-01.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; SH, Sima de los Huesos.

Footnotes

It is also well understood that some fundamental aspects of hearing, such as bandwidth limits, are determined by properties of the inner ear (34).

References

- 1.Rosowski, J. J. & Graybeal, A. (1991) Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 101, 131-168. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stokstad, E. (2003) Science 302, 770-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark, A., Glanowski, S., Nielsen, R., Thomas, P., Kejariwal, A., Todd, M., Tanenbaum, D., Civello, D., Lu, F., Murphy, B., et al. (2003) Science 302, 1960-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdelhak, S., Kalatzis, V., Heilig, R., Compain, S., Samson, D., Vincent, C., Levi-Acobas, F., Cruaud, C., Le Merrer, M., Mathieu, M., et al. (1997) Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 2247-2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vervoort, V., Smith, R. L., O'Brien, J., Schroer, R., Abbott, A., Stevenson, R. & Schwartz, C. (2002) Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10, 757-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masali, M., Maffei, M. & Borgognini Tarli, S. M. (1991) in The Circeo 1 Neandertal Skull: Studies and Documentation, eds. Piperno, M. & Scichilone, G. (Instituto Poligrafico e Zecca Dello Stato, Rome), pp. 321-338.

- 7.Nummela, S. (1995) Hear. Res. 85, 18-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elder, J. (1934) J. Comp. Psychol. 17, 157-183. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima, S. (1990) Folia Primatol. 55, 62-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitani, J., Hunley, K. & Murdoch, M. (1999) Am. J. Primatol. 47, 133-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivian, L. & White, S. (1933) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 4, 288-321. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson, L., Heffner, R. & Heffner, H. (1999) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 3017-3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown, C. & Waser, P. (1984) Anim. Behav. 32, 66-75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moggi-Cecchi, J. & Collard, M. (2002) J. Hum. Evol. 42, 259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher, N. (1992) Acoustic Systems in Biology (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford).

- 16.Rosowski, J. J. (1994) in Comparative Hearing: Mammals, eds. Fay, R. & Popper, A. (Springer, New York), pp. 172-247.

- 17.Rosowski, J. J. (1996) in Auditory Computation, eds. Hawkins, H., McMullen, T., Popper, A. & Fay, R. (Springer, New York), pp. 15-61.

- 18.Bischoff, J., Shamp, D., Aranburu, A., Arsuaga, J. L., Carbonell, E. & Bermúdez de Castro, J. (2003) J. Archaeol. Sci. 30, 275-280. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsuaga, J. L., Martínez, I., Gracia, A., Carretero, J. M. & Carbonell, E. (1993) Nature 362, 534-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arsuaga, J. L., Martínez, I., Gracia, A. & Lorenzo, C. (1997) J. Hum. Evol. 33, 219-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez, I. & Arsuaga, J. L. (1997) J. Hum. Evol. 33, 283-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirikae, I. (1960) The Structure and Function of the Middle Ear (Univ. of Tokyo Press, Tokyo).

- 23.Stuhlmann, O. (1937) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 9, 119-128. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray, H. (1977) Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical (Bounty Books, New York).

- 25.Johnson, A., Hawke, M. & Jahn, A. (2001) in Physiology of the Ear, eds. Jahn, A. & Santos-Sacchi, J. (Singular, San Diego), pp. 29-44.

- 26.Vallejo, L., Gil-Carcedo, E. & Gil-Carcedo, L. (1999) in Tratado de Otorrino-laringología y Cirugía de Cabeza y Cuello, eds. Suárez, C., Gil-Carcedo, L., Marco, J., Medina, J., Ortega, P. & Trinidad, J. (Editorial Proyectos Medicos, Madrid), Vol. 2, pp. 670-687. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aibara, R., Welsh, J., Puria, S. & Goode, R. (2001) Hear. Res. 152, 100-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onchi, Y. (1961) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 33, 794-805. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zwislocki, J. (1962) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 34, 1514-1523. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw, E. & Stinson, M. (1983) in Mechanics of Hearing, eds. deBoer, E. & Viergever, M. (Delft Univ. Press, Delft, The Netherlands), pp. 3-10.

- 31.Kringlebotn, M. (1988) Scand. Audiol. 17, 75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voss, S., Rosowski, J., Merchant, S. & Peake, W. (2000) Hear. Res. 150, 43-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puria, S., Peake, W. & Rosowski, J. (1997) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101, 2754-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruggero, M. & Temchin, A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13206-13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Relkin, E. (1988) in Physiology of the Ear, eds. Jahn, A. & Santos-Sacchi, J. (Raven, New York), pp. 103-123.

- 36.Rosowski, J. J. (1991) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 90, 124-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosowski, J. J. (1991) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 90, 3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dallos, P. (1996) in The Cochlea, eds. Dallos, P., Popper, A. & Fay, R. (Springer, New York), pp. 1-43.

- 39.Zwislocki, J. (2002) Auditory Sound Transmission—An Autobiographical Perspective (Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ).

- 40.Krings, M., Stone, A., Schmitz, R., Krainitzki, H., Stoneking, M. & Pääbo, S. (1997) Cell 90, 19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krings, M., Geisert, H., Schmitz, R., Krainitzki, H. & Pääbo, S. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5581-5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ovchinnikov, I., Gotherstrom, A., Romanova, G., Kharitonov, V., Liden, K. & Goodwin, W. (2000) Nature 404, 490-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Arsuaga, J. L., Carbonell, E., Rosas, A., Martínez, I. & Mosquera, M. (1997) Science 276, 1392-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arsuaga, J. L., Martínez, I., Lorenzo, C., Gracia, A., Muñoz, A., Alonso, O. & Gallego, A. (1999) J. Hum. Evol. 37, 431-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lieberman, P., Crelin, E. & Klatt, D. (1972) Am. Anthropol. 74, 287-307. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boë, L., Heim, J., Honda, K. & Maeda, S. (2002) J. Phonet. 30, 465-484. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fant, C. G. M. (1973) Speech Sounds and Features (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 48.Deller, J. R., Proakis, J. G. & Hansen, J. H. (1987) Discrete-Time Processing of Speech Signals (Prentice–Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ).

- 49.Kojima, S. (2003) A Search for the Origins of Human Speech (Kyoto Univ. Press and Trans Pacific Press, Melbourne).

- 50.Marler, P. (1978) in Recent Advances in Primatology, eds. Chivers, D. & Herbert, J. (Academic, London), Vol. 1, pp. 795-801. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lieberman, P. (1984) The Biology and Evolution of Language (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 52.Hopkins, C. (1983) in Animal Behaviour, eds. Halliday, T. & Slater, P. (Blackwell, Oxford), Vol. 2, pp. 114-155. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stebbins, W. & Moody, D. (1994) in Comparative Hearing: Mammals, eds. Fay, R. & Popper, A. (Springer, New York), pp. 97-133.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.